ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors.

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence (This PEN)

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

The evolution of the present global anti-corruption architecture started with a sudden burst of activity in the mid-1990s. What brought this original spurt of energy to something of a close was the agreement of UNCAC’s peer review mechanism at the Doha Conference of States Parties in 2009 – a milestone moment in this journey.

We shall follow international developments in the latter decade, post-2009, in subsequent notes dealing with relevant themes, but there is a distinct watershed in 2009 that makes the first decade very different from the second.

After 2009, we shifted from grand ambitions and establishing new structures to practical implementation. When that rubber hit the road, reality struck. If the first decade was one of realisation in the sense of ‘bringing into existence’ a suite of new instruments and tools, the second period was realisation in the sense of ‘coming to appreciate’ what we had actually signed up to.

It means the first decade is a story of creation, the second one of emerging challenges that in many ways have brought into question those original expressions of intent.

The prolonged tussle (four years and three Conferences of States Parties) over the shape of the UNCAC review mechanism, to which we shall return later, illustrates the emerging of this changing atmosphere. A close UNCAC negotiating colleague once reflected at the shift of tone once the Convention itself had been settled and when we had come to give it teeth through the review process: ‘The politics with UNCAC only kicked in after the Convention was agreed.’

During its crafting, the consensus was clear and agreeing the Convention in around two years was very quick time for an instrument dealing with such sensitive issues. It then took twice as long to hammer out how we would review ourselves, with many ancient suspicions and animosities rearing their heads again.

We shall dive into some of these controversies as we process through the main topics in future notes. But this preface serves to both explain the background to how and why the story is segmented in this way. Also, contrasting with what followed helps to reinforce once again how remarkable that initial period was in galvanising collective energy to be creative like never before.

A decade of unparalleled change

The significance of UNCAC warrants us starting here as it arguably transformed the debate on corruption beyond recognition.

This is not the place for a detailed factual description of UNCAC itself. There is an excellent commentary by U4 as well as a development practitioner-focused guide to its relevance for donors. Our interest here is how UNCAC changed the face of global dialogue. It needs to be celebrated for doing three significant things that changed entirely how people approached corruption. This value remains, although largely unrecognised.

It has removed three key ‘debatables’ which, before UNCAC, bedevilled making progress. It has allowed us to move past some old roadblocks that often prevented attempts to even talk about the problem.

Agreeing what corruption is

Firstly, UNCAC removes the debate about what is corruption. While there is no definition in UNCAC, it makes it very clear what constitutes corruption by setting out the array of practices that need to be eradicated, and the preventive measures that need to be put in place. This has brought us out of the past where contentions about cultural practices, claims of imposition of others’ moral viewpoints, and there being different standards in different parts of the world all often stopped the conversation on corruption its tracks before it had started. The West was accused of exporting its own morality. Others opted for the ‘when in Rome’-approach, which gave them pseudo-cover for perpetrating bad practices.

Now, with UNCAC, we have a set of behaviours that we all agree should be criminalised and rooted out. Without saying so, we actually have a consensus on what is corruption, and we can all point to the text that we’ve signed as a common agenda. UNCAC gets us past that old barrier.

Acknowledging the damage

Secondly, UNCAC makes it clear that corruption is damaging. Even as UNCAC was being created, there was still dispute amongst academics about whether corruption was, in fact, damaging at all. There was the ‘greasing the wheels’- and ‘it’s how things work here’-defence. A fierce debate existed on whether corruption was benign – or even helpful – in providing coping mechanisms for individuals and states. Supporters of this claim pointed to the ‘Asian Tigers’ of the 1960s and 1970s, appearing to deliver growth alongside corruption.

Here is not the place to dissect these arguments, but the consensus had been building from work done by the World Bank that gathered a body of evidence clearly showing the damage corruption causes to the chances of sustained and equitable economic growth. The UNCAC Preamble reflects that consensus. We all now agree that corruption is damaging. UNCAC gets us past that debate.

Clarifying joint responsibility

Thirdly, and finally, UNCAC solves the argument about who is responsible. In the past, those in developed nations would blame weak governance in poorer countries for the problem of corruption; those countries would point to the West’s banks being conduits for their lost money, and to external companies bribing for business. We often could not get past that polarised view.

UNCAC resolves the impasse by making it clear that both developed and developing countries have responsibilities. UNCAC is, in essence, a ‘grand bargain.’ It requires developed countries to up their game on the ‘supply issues’ that we in DFID embraced, such as commercial bribery, offshore financial centres, and asset recovery and return. It demands that developing countries strengthen prevention and improve governance. UNCAC gets us past that old debate.

So UNCAC, even if it does nothing else, has moved the ground significantly for us all simply by its existence – and with 187 parties it enjoys virtually universal acceptance. Having cleared away some of those past obstacles that hindered us, we can now point to common undertakings and understandings about what needs to be done. But UNCAC is far from perfect. In the final note, we shall look at some of its deficiencies – especially the review mechanism – as part of a collection of ‘challenges’ the world still faces.

Joining a fragmented landscape

While UNCAC brought together a critical range of issues for the first time, it is important to understand that it did little to replace anything. It might be seen as assuming centre stage as the broadest and most comprehensive instrument for anti-corruption the world now had, but it did not lead to the displacement of existing processes. Instead, UNCAC joined an eclectic array of international instruments, processes, and commitments that had grown up incrementally to deal with aspects of the problem from several narrow perspectives – both thematic and geographical.

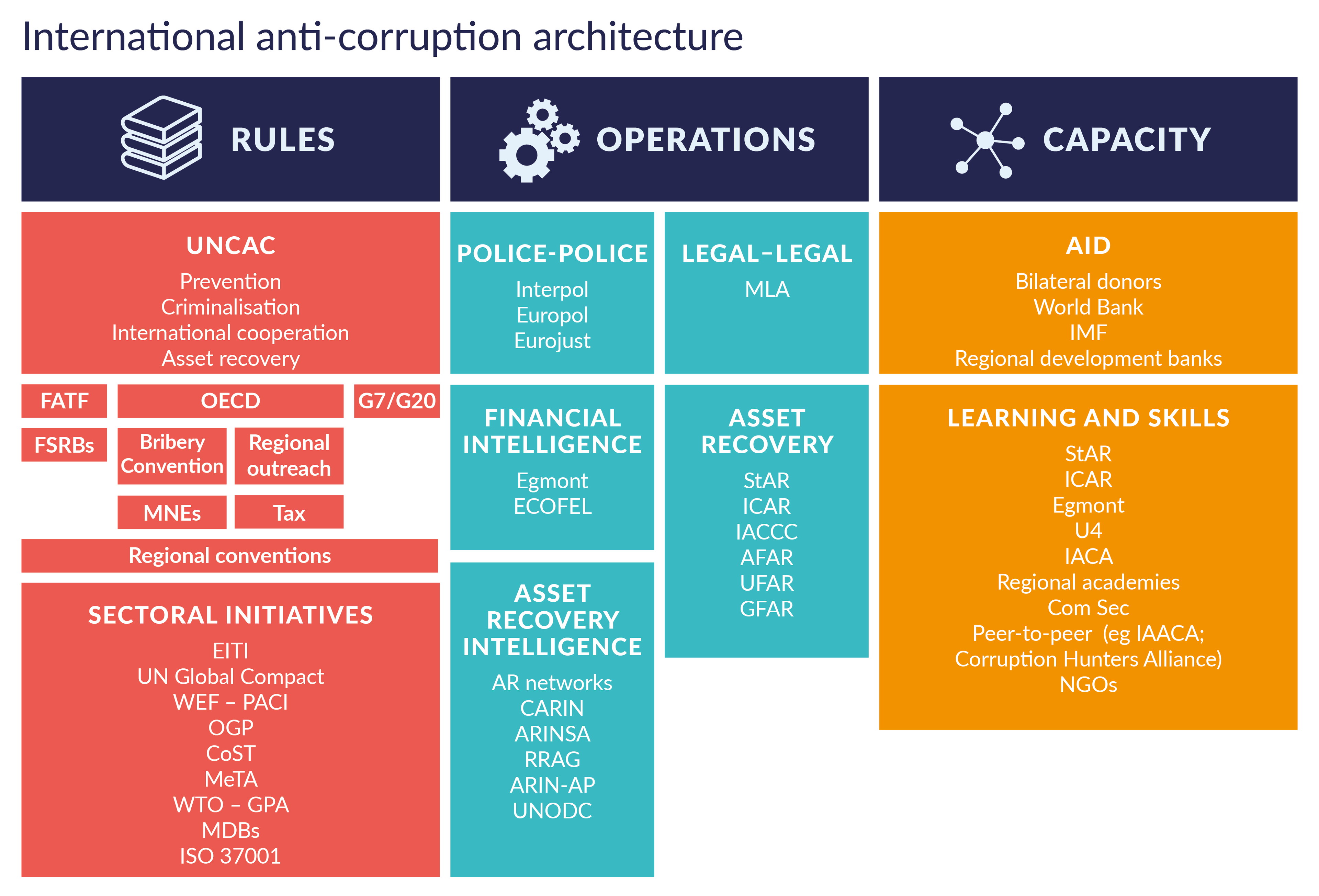

Getting to know the landscape is crucial. The chart below is my summary of a truly cluttered state of affairs. It helps to illustrate why the world is still some distance from a genuinely comprehensive approach to anti-corruption.

A battlefield of acronyms

FATF – Financial Action Task Force

FSRB – FATF-style regional bodies

OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

MNEs – Multinational Enterprises (guidelines)

EITI – Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

WEF-PACI – World Economic Forum Partnering Against Corruption Initiative

OGP – Open Government Partnership

CoST – Construction Sector Transparency Initiative (now the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative)

MeTA – Medicines Transparency Alliance

WTO-GPA – World Trade Organisation – Agreement on Government Procurement

MDBs – Multilateral Development Banks

ECOFEL – Egmont Centre of FIU Excellence and Leadership

CARIN – Camden Asset Recovery Inter-agency Network

ARINSA – Asset Recovery Inter-Agency Network for Southern Africa

RRAG – Asset Recovery Network of the Financial Action Task Force of Latin America

ARIN-AP – Asset Recovery Inter-Agency Network – Asia Pacific

MLA – Mutual legal assistance

UNODC – United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

StAR – Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative

ICAR – International Centre for Asset Recovery

IACCC – International Anti-Corruption Coordination Centre

AFAR – Arab Forum on Asset Recovery

UFAR – Ukraine Forum on Asset Recovery

GFAR – Global Forum on Asset Recovery

IACA – International Anti-corruption Academy

Com Sec – Commonwealth Secretariat

IAACA – International Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities.

All of these processes have grown up from different pressures and at different times. As seems to be the norm, once bodies get created, they persist, rather than allow themselves to be supplanted. Thus, our journey on global anti-corruption is the story of gradual accumulation of bodies rather than any strategic evolution. This has produced a battlefield of acronyms, often competing interests, and big risks of ‘review fatigue.’

This depiction does not attempt to register every entity in the global landscape but to show the most significant constituent parts of our present anti-corruption architecture. Its purpose is to illustrate the fragmented nature of the structure that practitioners must work with – presenting constant challenges of overlap and disjunction.

Some issues are not readily evident from this factual portrait but are critical for understanding how this multi-faceted system works in practice (and how it needs to improve). They also affect how a donor practitioner should approach it.

Three core observations to keep at the forefront of one’s thinking are:

- Rules – it’s much more important to implement them than to write them.

- Operations – it’s critical that skills are strong at both ends of the chain. It’s no good improving one’s own game if others aren’t equipped to benefit.

- Capacity – it’s crucial that this is about more than just knowledge; corruption is not something that gets solved simply because people have been given knowledge of how to combat it.

Rules: implementation, implementation, implementation

There are two reasons why the elaboration of rules is potentially the strongest component of the global landscape. Firstly, the explosion of rule-setting instruments has served to create commonality on what we are dealing with, as well as the basis for a level playing field for how everyone’s legal framework deals with it. But there is a second aspect that is magnitudes more important – the need to ensure that everyone enforces the rules. This is where our problems begin.

Commendably, the world has acknowledged the need for processes to review how well each jurisdiction is doing in living up to the commitments these instruments represent. The norm has become peer review – having other jurisdictions make judgements about one’s level of performance.

This has produced multiple review processes – a developed country like the UK typically is subject to at least five:

- UNCAC

- OECD Bribery Convention

- GRECO – the European Anti-Corruption Convention

- FATF

- Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (a relatively new exercise for tax transparency).

The UK also has been subjected to mandatory review by the EU’s anti-corruption initiative to vet member states’ legal and policy frameworks. In addition, there has been as a host of voluntary reviews under various sectoral initiatives the country has joined, such as OGP, EITI, and others.

Such a volume of reviews can stretch even the most organised and developed jurisdiction. It has not been unusual in recent years for developed countries to find themselves juggling almost simultaneous reviews. At one point the UK was under review process with UNCAC, OECD, and FATF at the same time. Developing countries are not immune from their own battery of processes, of which UNCAC, FATF, regional conventions, and the Global Forum on Tax are likely to apply to most. Developing countries have even less capacity to either properly engage in the review or train and prepare reviewers to conduct the ‘exam’ on others.

If this overloaded system led to strengthened performance, we might bear it as a necessary evil. But this is actually rarely the case as most of these processes look primarily at the formal system – whether the right laws are in place and the necessary institutions exist. The majority go nowhere near assessing whether those laws are in fact being implemented, and whether the institutions existing on paper actually operate in practice.

OECD convention

We have highly variable geometry in our anti-corruption landscape. The OECD Convention – the strongest convention in terms of the rigour of its scrutiny – covers only one narrow aspect of the corruption equation: the giving of bribes. It does not even cover the other side: the soliciting or receiving of a bribe. It enjoys, however, one of the toughest approaches to actually assessing whether a country is implementing its law.

UNCAC

By contrast, UNCAC’s all-embracing coverage comes at a price: the review process is utterly formalistic. Huge legal treatises are produced on the minutiae of every provision in a country’s anti-corruption law book, but virtually no story is told as to whether any of it is actually being used and to what effect. We will see in a forthcoming note how this came to be, but for now it must be recognised that there is a real shallowness at the heart of the UNCAC review process.

GRECO, OAS, and FATF

Other instruments lie somewhere in between. Long established regional instruments like GRECO and the Organisation of American States conventions seem to be more able to voice opinion on lapses in performance. The FATF process for reviewing anti-money laundering frameworks is the other main instrument that has moved in recent years into the ‘effectiveness’ space, rather than just checking the formalities are in place.

To conclude: the concern about ‘effectiveness’ has become the most important lens through which to look at the assortment of legal instruments countries have bound themselves to. Those which are still in the ‘formalism’ stage need to be pressed to move on, so that reviews can be genuinely meaningful in the practical world.

Operations: look both ways

A simple but often overlooked problem with operations is that donors can spend a lot of time improving a developing country’s ability to request formal legal co-operation from another (developed) country, but if the receiving country’s system is not also as well attuned to dealing with developing countries, the investment is wasted. As we saw with the UK’s experience in the previous note, DFID made sure that UK law enforcement was receptive to incoming requests from developing countries by creating its aid-funded special unit. It also assisted those developing countries, through direct help and by establishing StAR and ICAR, to be able to formulate their requests to the UK and others effectively.

This does not happen as routinely as it should. Since these matters will often be far from a priority for a developed country’s government, the role of the donor agency in being effectively the voice of the developing country in the domestic environment can be critical to success. More donors need to adopt such a stance, as envisaged by the second of the OECD’s donor principles on anti-corruption – referred to in the previous note.

A second issue that continues to frustrate operations is the framework for interaction between countries. Ensuring easily accessible contact points in other jurisdictions to enable rapid exchange of information when required is a common demand. In recent years, a suite of new networks has emerged:

- The Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units – a collection of focal points on financial intelligence

- Interpol’s network of police focal points

- In the early 2010s, UNODC established a new global network of focal points for asset recovery contacts under the auspices of the UNCAC Working Group on Asset Recovery and the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative. It is now hosted by Interpol.

These initiatives joined the pre-existing regional asset recovery inter-agency networks CARIN (Europe), ARINSA (Africa), RRAG (Latin America) and ARIN-AP (Asia-Pacific).

Arguably, the problem we have is that there are too many focal point networks. Each one has a specialism – intelligence, police investigation, asset tracing/freezing – presenting a requesting country with a dilemma of who to contact. At the same time, both requesting and receiving states still need to coordinate across their own focal points. Some fresh thinking on how to reduce the potential for delays from this proliferation of channels and partitioning of information is necessary.

Capacity: knowing is not enough

We now enjoy a vast repository of knowledge and learning on anti-corruption. For nearly 20 years the U4 has been the backbone of the donor agency resource, producing material specifically tailored to development practitioners. This provides an invaluable foundation for bettering our understanding and our approaches. But if there has been one lesson from the past two decades, it is that knowledge alone is not enough. Yet our approach to ‘capacity building’ for tackling corruption has almost all been about transferring knowledge. It is the purpose of all of the entities listed in the capacity column above.

Think about a classic anti-corruption programme from a donor. This will likely include one (and usually more) of these activities:

- technical assistance and equipment

- toolkits and manuals

- training

- mentoring

- study tours

- legal drafting

- policies, strategies, and plans

- institutional development.

All of these have the aim of conveying knowledge, as if knowing how to confront corruption is what it takes to succeed. But decades of this form of assistance has barely seemed to affect the problem, and yet we have we rarely ventured beyond this menu.

For a host of reasons, donors find it easiest to stick to this. It is what donors are set up to do and it aligns with how they approach every other developmental challenge they contend with. But clearly something else is needed alongside this – not least to recognise that corruption is not a technical problem capable of a technical solution. It is deeply political. The skills that are needed for this go beyond what donors are currently set up to provide. This is the hole at the heart of our orthodox response.

We shall explore this conundrum further in the tenth note when we consider a range of remaining challenges that donors face. But the message for now is that we need to think beyond knowledge.

--------------

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – a tale of two decades – from ambition to ambivalence (this PEN).

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)