ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors.

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

The prevailing donor mind-set

To gain a sense of how far the new approach departed from the norms of the time, we need to understand the prevailing donor mind-set that then ruled (to the extent that anyone actually thought about corruption).

Donors looked on corruption almost always as a problem ‘over there’ and ‘with them.’ Where anti-corruption policies were developed, these focused on assisting with institutional reform in developing country systems and protecting aid funds from being lost there through corruption. They also promoted emerging international norms. Examples include UNCAC and corporate social responsibility processes, which highlighted to commercial businesses their responsibilities when operating in these countries. Almost none considered the role of their own country systems in the problem.7fedab7b31ed

So, donors embarked on their anti-corruption journeys seeing the problem through their traditional developmental lens. Not surprisingly, the responses that resulted tended to mirror traditional development assistance modalities – training, ‘capacity building,’ and institutional strengthening in the countries themselves. We shall return to this later in the series as it turned out to be a fateful direction to take. But the crucial point for our story was the unspoken consensus that all the action was regarded as having to take place in the ‘victim’ country.

In the UK, the departure point under Clare Short was very different, as recounted in part 1. We began with a wider set of concerns, worried just as much about the UK’s ‘supplier’ role as about the effects in partner developing countries. Hence the empowering of a strong centralised effort at headquarter-level to cast DFID’s net much wider than just a development agency’s traditional objective: helping poor countries with their problems. Ministers gave staff in DFID the political authority, in regard to global corruption, to start to address the UK’s problems.

Thinking in multiple domains

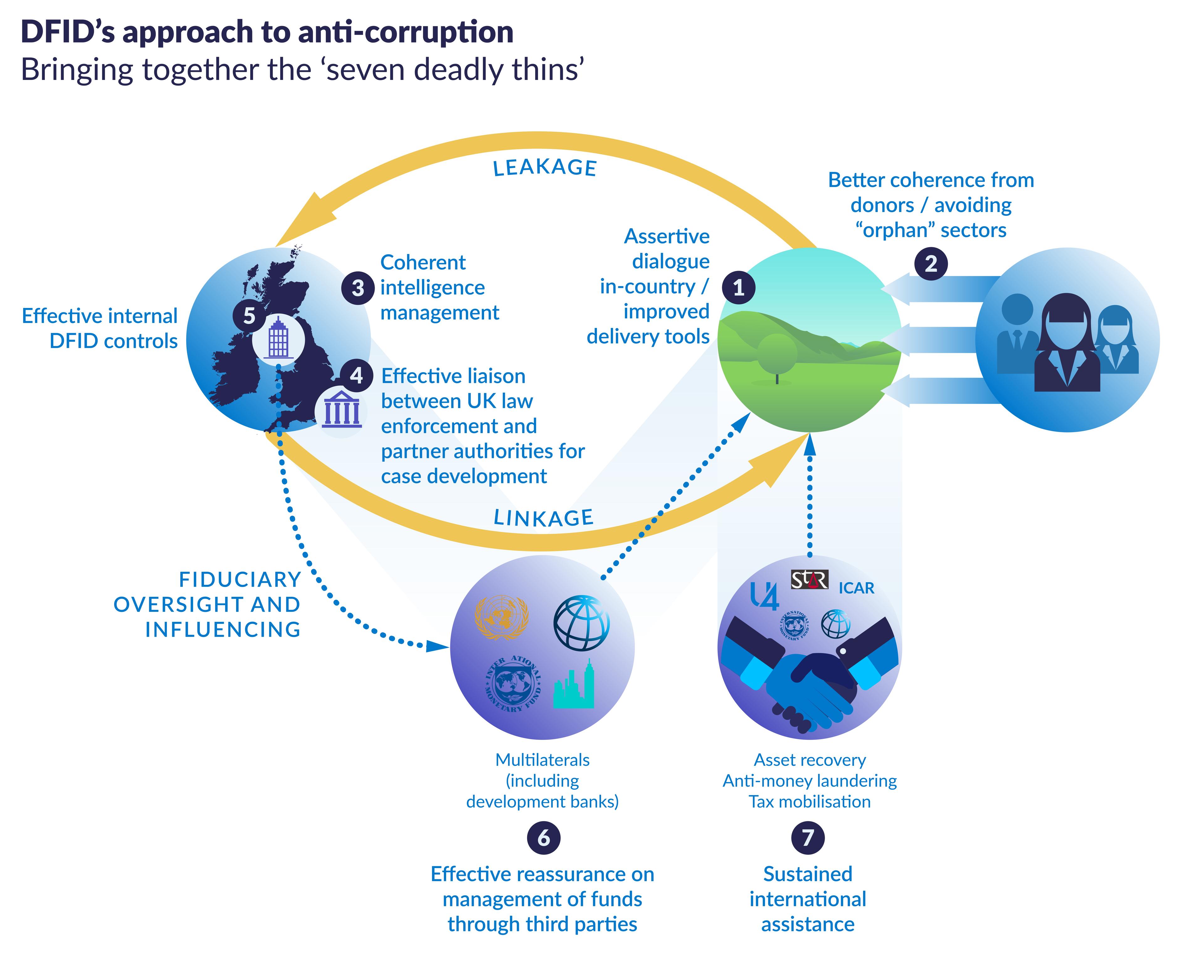

At DFID we conceptualised the key dimensions of the problem we faced – what we saw as the ‘seven deadly thins.’ These were domains where the way we operated created weak points that allowed corruption to fester. Addressing each of the concerns needed to be a part of our response, and was a fundamental shift in how we worked. The diagram illustrates where the ‘deadly thins’ were present and addressed.

The seven deadly thins required us to think in multiple domains – in our partner countries for sure, but more broadly, too: at home, and at the inter-state level. This was because corruption even then was showing itself to be an inherently cross-jurisdictional problem. In 2000, the world completely lacked the tools to do much about that aspect, as we shall consider in the next part.

None of these weak spots have been completely repaired even after 20 years. We will explore in later parts some of the reasons why. But despite the daunting challenge each presented, it is inconceivable that there could be any genuine progress without trying to address each of them and to appreciate their inter-connectedness.

The problems we set out to combat sit in three domains. At country level, donors tended to treat corruption as just another of the development challenges. It was to be met by using the standard suite of responses. We almost always demurred from moving beyond this comfort zone for all sorts of reasons which we’ll look at in detail in a dedicated part towards the end of this series. Donors set out to train people and pass on knowledge about how to defeat corruption. That is what donors do for everything else – that is how they approached corruption.

Donors also failed miserably to co-ordinate amongst themselves. They often sent mixed messages to the host country about whether they cared about corruption or not. They behaved disjointedly when corruption episodes erupted, and cherry-picked what were felt to be easier targets to devote programming to. At the same time, they ignored the complex nature of the problem – challenges demanding a far more coherent approach across multiple sectors all at once. We will return to this as a lesson learned later, too.

A typical anecdote

One donor’s approach was to put huge efforts into reforming the police in one Asian developing country. It was said that they were now capable of actually investigating corruption cases and bringing them to court. But no one had reformed the judiciary. So all the police reform was for nought. The word on the street was that ‘you can’t bribe the police anymore – you just need to buy the judge.’

Staying just at the partner country level (thins 1 & 2) could never begin to make inroads into the problem. But at the time this is where the donor effort began and ended – and, sadly, where it still remains for far too many donors today.

A country like the UK had to recognise that enormous amounts of public resources were leaking out of the countries we were trying to help through aid. And that these leaked funds were coming into the UK financial system. The examples at the time were stark, showing that the consequences of corruption often dwarfed the volume of our aid going in, as box 2 illustrates. Few donors had ever thought about things in this way.

More leakage than aid – examples

Nigeria received US$ 1.1 billion of official development assistance (ODA) during the Abacha regime, 1993–1998. In the same period, he and his family looted up to US$ 6 billion.

In 2002, the African Union estimated that corruption cost Africa US$ 148 billion a year. This compared with Africa’s ODA inflow of US $22.3 billion in the same year.

A DFID-funded money laundering study in 2002 estimated that US$ 22 billion of criminally-acquired funds was laundered annually in the East and Southern Africa region. This would meet nearly half the amount of ODA that Nelson Mandela’s campaign was then calling for to meet the annual development needs of all of Africa.

In five years (1998–2002), estimates showed US$ 4 billion of Angolan state oil revenues to have failed to reach the national accounts, more than double the amount Angola received in development assistance (US$ 1.74 billion) in the same period.

For the first time, a donor agency looked inward and aimed to change the policies of its domestic departments – often against their inclinations. At the time, two huge issues loomed larger than any others and these formed the core of that effort: the absence of credible anti-bribery laws and the absence of any credible response to the flood of illicit funds coming from poor countries into the UK’s own system.

Securing a gold-standard Bribery Act

DFID kept up a driving role from start to finish – from the first letter that Clare Short wrote to the then Home Secretary (the UK’s justice department) in 2001, demanding that the UK up its game on penalising bribery abroad by our companies, to the eventual passage of the Bribery Act in 2010. What emerged is now regarded by the OECD as the global gold standard for anti-bribery legislation.

We deployed three arguments. The first was wholly about aid: DFID could not achieve its goals in encouraging partner countries to do better at fighting corruption themselves, if these countries could point the finger back and say ‘it’s your companies that come here and bribe for contracts.’ We had a clear case for the harm our companies were doing to our aid effort.

But we had two rather better political arguments. (We realised that other departments had to be won round on arguments that registered with them, not those which mostly only mattered to us – we will explore this fundamental approach to influencing in a later part.)

On the one hand, the OECD was issuing scathing reports against the UK in reviews of our compliance with its new Anti-Bribery Convention, which we had signed in 1997. Politically, this mattered as the UK was not used to such a level of negativity from the OECD, membership of which counted high for UK’s prestige. We in DFID learned how to use this external pressure to buttress our arguments. On the other hand, the government found itself in an increasingly ludicrous position of having to defend the status quo legislation which – extraordinary to anyone in the year 2000 – dated from 1889, 1906, and 1916. That there had never been a prosecution for foreign bribery under these laws was, bizarrely, argued by some of our opposites in government as testimony to their good deterrent effect!

These arguments – aided by a strong DFID ministerial push – helped initiate the journey. It would take ten years to reach the end point, not least because of ingrained resistance from within to ditching the long existing legal construct of corruption which was centred on the principal-agent theory. Under this, corruption or bribery occurs when the ‘agent’ (eg a company salesperson) abuses the trust they have with their ‘principal’ (their company director) who expects them to secure a contract cleanly, by taking a bribe.

The UK’s first attempt to modernise our laws was structured on this basis. It was widely condemned by the House of Lords pre-legislative scrutiny process as being far too complex to understand. Curiously, the fundamental flaw in all of this had escaped the drafters. DFID quietly pointed out that the whole ‘principal-agent’ approach to defining bribery collapses if the principal actually approved the payment of the bribe. Then there would be no ‘corruption’ of the relationship between the two. To us – and the silence on the end of the phone suggested my opposite number had not quite thought of it like that – it seemed that anyone could escape a bribery charge by simply saying they were following orders. Remarkably the approach quickly disappeared.

Once past this mental roadblock, the way was clear for a modern law, based on the UNCAC approach of simply seeing bribery as the giving or receiving of an undue advantage.

The UK Bribery Act is seen as a global gold standard because of three key elements which make it stand out from all the others:

Extra-territorial jurisdiction

UK citizens and foreign nationals working for UK-based companies can be prosecuted in UK courts regardless of where the act of bribery actually takes place. It was a huge problem under the earlier laws that prosecutors had to show that some part of the act had taken place within the UK in order to claim jurisdiction. It obviously did not take much for criminals, even the least sophisticated, to ensure that all the action took place beyond UK shores, and that effectively deprived us of being able to do anything. Taking jurisdiction on the basis of the nationality of the perpetrator, rather than where they perform the act, has transformed the position of our law enforcement.

No facilitation payments

There is no loophole permitting payments, as there is, for example, under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Any undue payment, of whatever size, constitutes a bribe. This was hugely controversial, for obvious reasons. Companies were concerned that they might not be able to conduct ‘business as normal’ in many developing country markets. They worried whether small payments extracted under duress at armed checkpoints at the dead of night counted. They wanted clarity on whether the kinds of hospitality they regarded as a regular part of business practice, such as tickets to sporting events, counted.

One UK business who wanted to keep facilitation payments pressed DFID to help their cause by asking us to ‘explain the realities’ to lawmakers of doing business in developing countries and support the concept of a minimum threshold below which payments could be made. We refused.

It was not a matter of amounts, we felt. There was a very clear point of principle here. DFID was spending a lot of effort in developing countries to get governments to take action against their own public officials who were extracting small bribes on a daily basis from citizens for services that should be free. To be seen to be giving legal cover to our own businesses for fuelling those very practices deeply undermined all the work going on to improve the integrity of local officialdom.

So the UK law makes no distinction. There are safeguards in our prosecutors’ practice manual that protects those caught up in unavoidable payments when under duress. What amounts to a duress defence, what is reasonable hospitality, and what is out of bounds will be established over time under the British case law system, as cases come to court.

Corporate responsibility

The third stand-out element was highly innovative, but crucial in our mind to give the new law added teeth. It was one for which DFID lobbied hard. Few, if any, other countries have gone so far. OECD has lauded us for being ‘state-of-the-art.’

The corporate responsibility provision enables the directors and senior management of a company to be prosecuted for bribery, even if they had no direct part in the actual act. They are held to account for being in charge of a business organisation that failed to prevent such practices. This takes a major step forward in sending strong deterrence messages to the top leadership of businesses, who can now find themselves in the firing line if one of their staff bribes. It is no longer the easy way out simply to find the rogue staffer and dismiss them.

In these three ways, the UK Bribery Act has set a global standard. Many of the provisions are yet to be really tested in courts, but that is not unusual in the UK legal tradition.

Stemming the flow of illicit finance

Our other watershed development was the way in which we set about combating the leakage of developing country finance that was coming into the UK’s own financial system. In an ideal world, we should simply have needed to look to our law enforcement to take action. But matters were, unsurprisingly, not quite as simple as that.

Our ambition to see our domestic agencies taking on money laundering (and foreign bribery) cases originating in developing countries came up against a number of obstacles. They were very practical, and derived not from a lack of underlying will amongst law enforcement, but from the realities of constrained resources and the tyranny of prioritisation.

One thing became clear to DFID from early contacts with law enforcement: it was unrealistic to expect that most cases coming out of developing countries would receive much attention when competing with those cases coming from other, mostly developed, jurisdictions. This was due to the over-demand placed on stretched resources.

The logic of the argument we heard was incontestable: the kinds of investigatory capacity needed for complex international cases is highly specialised, and in short supply. Inevitably, there has to be prioritisation. A set of considerations has to be applied by domestic law enforcement authorities in reaching judgments about where to devote scarce resources. These would, as a matter of course, militate against cases coming from developing countries, for a number of practical reasons.

Given the hard choices they must make, we found that law enforcement will opt to deploy their scarce internationally-facing resources:

- On the biggest cases.

- To countries where they have established and trusted working relationships, especially at the practical operational level.

- Where there are good chances of co-operation on legal matters.

- Where the prospect of gathering and exchanging evidence is strong.201712d38e9b

All of these factors weigh heavily against the interests of developing countries:

- Often the cases are too small – comparatively – to rank high enough in prioritisation decisions. However, while a case involving, for example, GBP 20 million may be magnitudes smaller than what law enforcement will be dealing with from another developed country, this amount may be a very significant sum proportionately in the finances of a developing coountry. But they get squeezed out.

- It is a well-acknowledged reality that law enforcement officers are more successful doing business with opposites with whom they have worked with before and with whom they have developed a degree of professional confidence and trust. Not surprisingly, DFID found that law enforcement in a developed jurisdiction like the UK is likely to be happier and readier to deal with international cases from other European countries, or from North America, or other developed jurisdictions. Such cooperation will look to be a far more predictable and familiar prospect than working with a developing country. So, again, the developing country loses out.

- And even if it is judged important to engage with a developing country – on practical terms and with the best will in the world – the quality and predictability of doing what is required on evidential case-building is important. This will usually be seen to be riskier and more difficult with an unfamiliar developing country than with a traditional partner.

Spending aid at home – a unique donor response

DFID recognised that, if due attention was ever going to be devoted to asset recovery cases coming into the UK from developing countries, additional input was going to be essential. Something had to help counter the inherent disadvantages these countries face in the domestic competition for scarce law enforcement resources. So we looked to our aid funds.

Spending aid at home, at first sight, might look counter-intuitive. But it supports activities that are, in essence, no different to those that donor agencies have long supported in partner countries, such as by supporting anti-corruption agencies. The ultimate purpose of the activity – recovering stolen assets for their return for productive developmental use – satisfies both the ODA-eligibility rules and DFID’s own legal confines which require that all aid is used for the primary purpose of poverty reduction.4a83b43b5caf

In 2006, we therefore set up two aid-funded law enforcement units, the Proceeds of Corruption Unit (POCU) in the Metropolitan Police to pursue money laundering and illicit flows into the UK from developing countries, and the Overseas Anti-Corruption Unit (OACU) in the City of London Police, addressing bribery by UK citizens and companies in developing countries.4d5945bf56be We also aid-fund the supporting components before and after the investigation phase – one team dedicated to initial intelligence gathering, and another dealing with post-conviction asset recovery.

In the years since their creation, the units have achieved over 30 successful convictions for bribery or money laundering, including the first politically exposed person – James Ibori, former Nigerian state governor, convicted in the UK of money laundering using stolen Nigerian public funds. Over GBP 400 million has been restrained or recovered in the UK, and the teams have helped to get nearly as much again in overseas locations. The work exhibits a high value for money return. For example, in 2017, for every pound spent on resourcing the unit, it restrained 114 pounds in illicit funds.

U4 reviewed the early years of this work in a in 2011, giving further background on the origins and evolution of the teams.

The ICU remains the world’s only aid-funded law enforcement unit in a developed country, dedicated to tackling developing country corruption. DFID’s particular circumstances in the early 2000s helped to create the momentum and opportunity for this unique donor response. But it remains something of a mystery why others have not followed suit, especially as donors collectively recognised the importance of the approach when they agreed the first OECD anti-corruption principles in 2006 – a central element of which was the need to recognise and take action on the ‘supply side.’

The ICU, as it has always done, remains ready to advise any other donor agency or law enforcement entity contemplating establishing a similar venture. We have always relished the prospect of seeing more of them come into existence.

–––––––––

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey (this PEN)

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, the 2006 Fighting Corruption – SDC Strategy was something of an exception. It recognised Switzerland’s role in ‘capital flight,’ setting an objective to ‘bringing the issue (…) to the attention of the international community with the aim of addressing its root causes and impact on developing countries (so still a rather ‘them’ focus on the problem). It did, however, commit to advocating for stronger efforts on asset recovery and repatriation, given Switzerland’s emerging experience on this front.

- It must be accepted that there is also an inherent tension facing domestic law enforcement authorities that are democratically controlled and subject to the priorities of the people who vote in elections. Domestic tax payers expect them to concentrate on domestic law enforcement priorities.

- OECD DAC statistics department has confirmed DFID’s reasoning that support for such purposes in the domestic environment is eligible to score as official development assistance.

- In 2015, these merged to become the International Corruption Unit (ICU), based in the UK National Crime Agency.