ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors.

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (this note, final in series)

To conclude this initial set of reflections, I want to consider two critical fault lines that have emerged from our first two decades of combatting corruption. They seem to me to be important factors that have contributed to the waning of optimism and drive that we have seen in recent years.

In my judgment, here lie the crucial fixes that we now need to make. They call for radical changes to the way we think about our work. They will not be straightforward, or perhaps even possible. But they will be the core challenges that anti-corruption practitioners will face in the next phase of the journey.

The end of the beginning

As I contended in note 3 on the origins of the international architecture, the first 20 years were ones of optimism and ambition. Although there has been a falling off of both as time has progressed, they can also be seen as years of building critical foundations. Without some essential components there could have been no prospect of even starting the anti-corruption journey. For example, the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) created a formal consensus that helped everyone to at last get to first base, and the International Centre for Asset Recovery (ICAR) and the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR) were agents of practical change in international co-operation.

But having laid these and other foundations, a step-change is now needed if the waning impetus that has fallen over anti-corruption is not to take a firmer hold. The next period must be one of adapting methods, drawing lessons from what we have gone through, and being willing to throw away old approaches that have not proved up to the test.

Moreover, we must also retain our optimism. We must not become too jaded and consider the alternative to all this – giving up. The future will be just as fraught with complexity, and disappointments no doubt, as the past has been. But there are strong arguments, with which I will conclude, that show there is a compelling case for persevering.

The current illusion of anti-corruption

There are two stand-out problems with the current state of anti-corruption seen from a development assistance perspective. Our failure to acknowledge them is creating a comfortable illusion that corruption is being addressed when, in fact, the fundamentals driving corruption are not really being touched. The two problems are:

- in terms of the arrangements for collective international accountability, the present system – the UNCAC review mechanism – falls woefully short of a genuine test of a country’s performance against corruption; and

- the present donor approach to anti-corruption lacks conceptual credibility and is always likely to be at risk of being undermined by a donor’s other priorities.

It is not easy to see how these problems can be addressed. Yet stating them clearly allows us to chart the targets and the direction of travel. The alternative, where I fear we are now, is to continue to drift on a sea of self-delusion.

UNCAC – going through the motions, mechanically

The value of UNCAC as a set of mutually agreed commitments, is undoubted. My review in note 3 made this clear. It fundamentally changed the global discourse. Without UNCAC, we would still be going around in circles. But as we saw in the review of evidence in note 4, implementation is everything. And it is here that things have gone badly wrong.

UNCAC’s review mechanism was negotiated amid high suspicion on all sides. These talks took from 2005 until 2009 – longer than to agree the convention itself – mostly because of fear. It is a curiosity of the final product that the shape it has taken reveals more about what participants wanted to avoid than a positive design to ensure optimal value from the review exercise.

There was fear on the side of the developing country constituency, the largest voice among the participants, that the mechanism would be unacceptably ‘intrusive’. The fear from others, particularly the donor countries who argued for openness and rigour of scrutiny as strong drivers of reform, was that a mechanism that did not genuinely challenge would be ‘an expensive fig leaf’. As such, it would allow real problems to be masked while simultaneously consuming precious resources (time and financial) that could otherwise be used for practical anti-corruption efforts themselves.

Civil society feared that the decision-making methods adopted in UNCAC – agreement by complete consensus, effectively allowing any objector to thwart the views of others – would mean that those who were least ambitious would end up shaping the result.

And that is how it turned out. The participants went at the pace of the ‘slowest ship in the convoy’, incorporating only what was acceptable to those most reluctant to be scrutinised. It leaves the mechanism suffering from a number of deficiencies: in the process, in the product, and in the subsequent scrutiny. These gaps have, in practice, left the corrupt shielded from any real challenge and accountability.

The process

The bloc of developing countries feared the reviews could lead to the creation of a league table, like the Transparency International (TI) Corruption Perceptions Index, that ranked performance. They therefore held out against any form of comparison between countries. They also insisted on universal coverage (unlike, for example, the approach used by the Council of Europe GRECO process that selects themes from within the overall convention to review). This means the mechanism requires an article-by-article, section-by-section, slog through its entirety.

As a consequence, the decision was made to split the review into two cycles, taking different parts of the convention to evaluate separately.c1c1bdc2f764 The mechanism therefore has a built-in inability to be able to take a holistic view of a country’s position, thereby undermining one of the supposed intentions of the review – to provide a picture of a country’s assistance needs. With the initial cycle proving to take far longer in practice to complete than originally estimated, a country’s two reviews can easily be anything up to a decade apart.

Openness was further dampened by permitting countries to avoid having physical visits from their reviewers.5034cb66ecb4 There is no obligation either for a country under review to involve non-governmental stakeholders.

The product

The anxiety over ‘intrusion’ and comparisons of performance means that the review takes a highly legalistic approach. ‘Compliance’ with the convention is seen strictly in formal legal terms – the existence of laws, bodies, and procedures – over whether these are actually being used and to what effect. Reports must avoid making overt judgments on countries’ operational shortcomings. And finally, even with these restrictions in place, the rules allow a country not to publish the full report.b7ec5b29b45b Only a short Executive Summary is mandatory.

What this system produces can be seen in the repository of country reports – for those that agree to publish them: thousands upon thousands of pages of dense legal analysis, with no real insight into how any of it is actually being applied.

The scrutiny

And that, folks, is it. Unlike other UN review processes, there is no place in this mechanism for plenary discussion of reports. There is no further action on a review report beyond its posting on the UNCAC website. There is no challenge from other state parties to the convention, no defence is required, no explanation is needed.

Any cost–benefit analysis of the UNCAC review process would likely come out heavily on the cost side. The benefits feel acutely marginal in comparison to the time, money, and effort that it all takes. We seem to have invented a process that, at the same time, consumes huge resources, both of human energy and scarce finance, but produces very little of practical use. We still do not know, after all this endeavour, how well any country is actually doing on tackling corruption.

Donors – going through the motions, with blinkers

The second conceptual universe that cries out for re-visioning is donor practice. My views of the frailties of our orthodox approach have been trailed in earlier parts of this series. As I sought to show in note 4 on evidence, and in Five reasons why aid providers get it all wrong on anti-corruption, our operational tramlines serve to shape and constrict the way we set ourselves up to address the problem.

In note 4, I proposed four strategic lessons that donors need to absorb:

- That the governments we deal with are part of the problem, and need to be seen as such. Donors need to stop deluding themselves that their ‘partners’ share an equal ambition to tackle corruption.

- That ‘politics’ matters. A purely technocratic approach, which donors are most comfortable with, will not succeed.

- That there is a need to both repair weak systems and the incentive structures in society. Currently, in many developing countries, malfeasance is incentivised over integrity, and manifests itself as impunity.

- That the interdependencies of institutions matter.

A new proposition with some fresh truths is needed.

- Rather than naively treating other governments as partners in this endeavour, we need to bring pressure to change errant behaviour and reduce their room for manoeuvre in being corrupt.

- We need to shift our vision to see that combating corruption is principally about incentives, not knowledge alone. It is not something that can be left to governments to do themselves of their own volition. They need to face pressure to tackle corruption from their citizens.

- As donor agencies, we need to broaden our horizons and bring to bear all the levers that an external influencer has to change the political calculations made within a system affected by corruption.

- And we need to be prepared for serious fallout. Too often for donors, and their governments, the long-term anti-corruption battle plays second fiddle to other, shorter-term, interests.

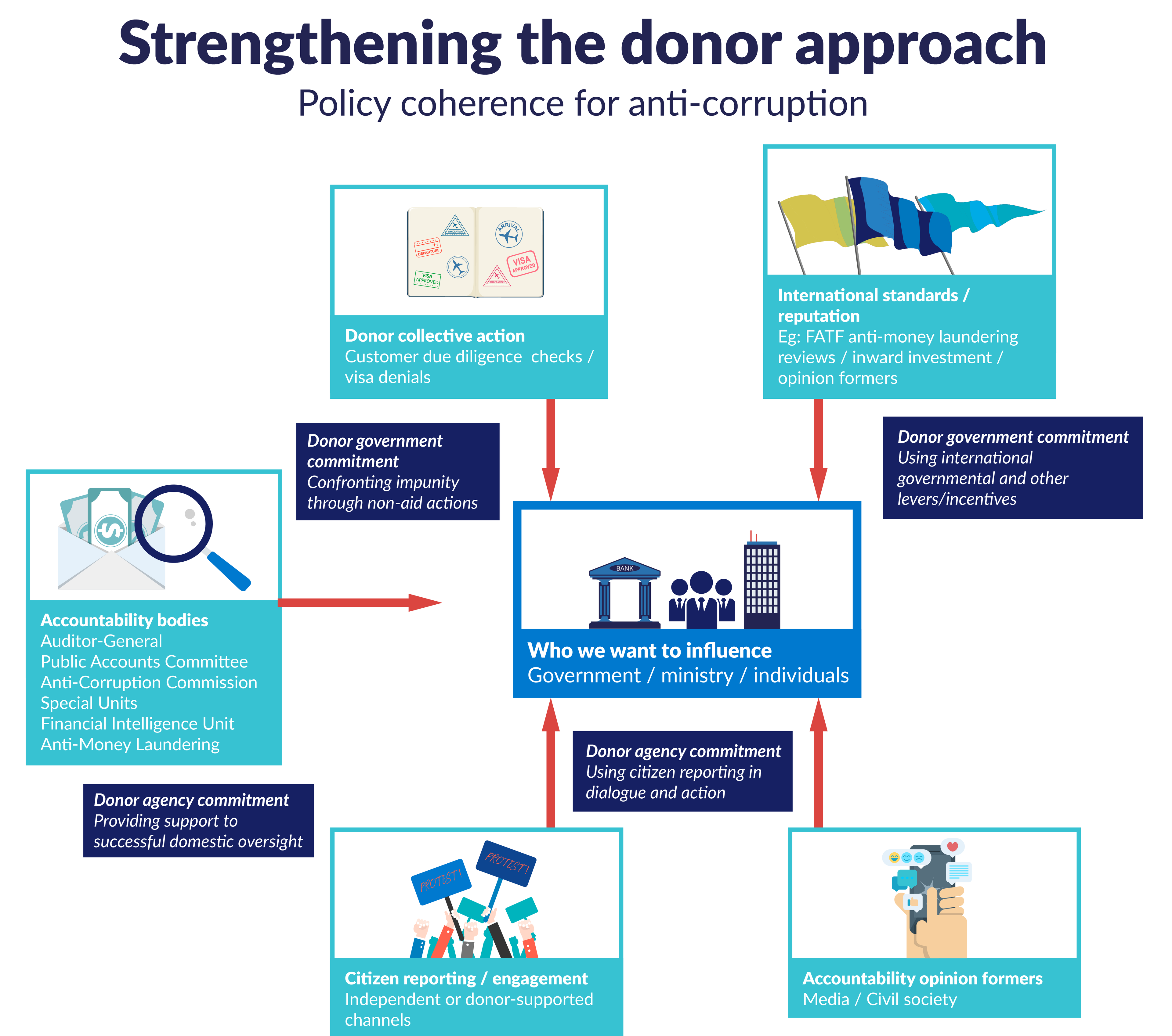

How it might work – a sandwich approach

Rethinking our current approach, which presumes that the mere transfer of knowledge of how to tackle corruption suffices, to focus on creating pressures for change offers a range of new opportunities. We can help strengthen the citizen–state nexus, which experience shows can be a major stimulus of action. We can ensure that formal accountability bodies get the resources they need, connect better, and see things through to the end. We can bring new ‘non-aid’ leverage that changes political calculations and shifts behaviours.

The concept of the ‘sandwich approach’ is not new. It was spawned most energetically in the early 2000s in the rapid transitions of Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Here vibrant civil society groups fresh from the popular revolutions pleaded with Western donors: ‘we have shown we can put pressure on our governments from below, we need you to put pressure on them from above.’ Together, the ‘target’ (which can be a government as a whole, a specific ministry, or, indeed, a specific individual) finds their room for manoeuvre reduced.

Pressure from below

It is clear that, compared with other parts of its government, a donor agency has a comparative advantage for on-the-ground assistance. Here its optimum contribution is in mobilising citizen voice, fostering an active media, promoting the reporting of corruption by service users, and encouraging open data and freedom of information for use by citizens. All of these help to shape opinion and momentum.

Pressure from the side

This angle of attack is the most common strand of existing donor assistance, supporting the formal bodies of horizontal accountability in the system. But current approaches tend to be too limited. They merely look to train the staff of these bodies, and often in isolation from others whose combined efforts are essential. Thus, much support is given to Auditors-General who might identify lapses, but then their reports languish in a poorly operating Public Accounts Committee. A ministry’s internal audit might identify crimes, but then these are passed to a poorly operating law enforcement, where nothing then happens.

The essence of a new approach to horizontal accountability is for donors to commit to ensuring that all the links in the accountability chain work better together. None should lack the skills, equipment, or seconded operational expertise to pursue a corruption finding to its final conclusion.

This will mean novel forms of support, for example, in forensic accounting, asset tracing, or prosecutorial assistance to supplement local capacity. Those providing assistance need to be both flexible and capable of moving beyond the usual types of support given by the aid agency.

Pressure from above/outside

In terms of pressure from above or the outside, orthodox aid-based forms of assistance are supplemented by ‘non-aid’ leverage, both negative and positive. This requires contributions from other parts of government, particularly the diplomatic service, trade promotion departments, and domestic regulators. Understanding which levers have greatest potential is vital, and will differ from country to country. It is about asking ‘what matters’ to the government one is trying to influence.

Direct and negative actions, like visa bans and exclusions of corrupt individuals, can play an important symbolic and deterrent role. Tough scrutiny of beneficial ownership of assets held abroad can do likewise. For some, as we found at the Department for International Development (DFID), the views of international credit ratings agencies matter deeply.

In one episode, the donor response to the government’s inactivity on anti-corruption – a common one of slicing a portion off the planned aid total in the coming year – made no difference at all. The government simply wanted clarity on how much it would lose (since predictability of flows still mattered), but was otherwise unfazed by the donor action.1be368b16f2d However, when one of the big three agencies lowered the country’s credit rating in the light of the perceived corruption risks for investors, the government took both notice and action. Its global credit status clearly mattered to it more than aid cash: donors had been misguided to think reducing the flow of aid would bring about change.

On more positive ground, fostering influential local views to highlight the negative impact of corruption on the business and investment climate can help mould the local climate of opinion. This can lead to demands for change from those who can see they could lose out from opportunities.

The combination effect

It is when all three sets of pressures can be brought together in combination that transformative change looks possible. This approach does require altering a number of ingrained current practices. Donor agencies must work more closely with other parts of their own governments. Thereafter, they must work more closely as combined units, with other governments providing assistance to sustain a stronger common front than we see now.

Moreover, the new approach bumps up against some elemental aspects of the donor world. It means getting tougher with recalcitrant or non-performing countries, which risks donors not being able disburse all their allocated budgets. It involves bringing other parts of the relationship into play, which diplomatic colleagues always find uncomfortable. It means being prepared for a ‘show-down’, which again makes diplomats nervous, and leaving oneself isolated if others are not as determined to hold out.

Hence the combination effect has not proved easy to operationalise and remains a work in progress. But it is hard to see the donor community making further progress on anti-corruption without this kind of fundamental rethink. Domestic taxpayers, who fund donor aid, have shown themselves increasingly intolerant of the slow-moving story on anti-corruption. This is transferring into reduced support for aid in general.

A final word: holding firm

These are two huge challenges which will require a lot more endeavour in the years ahead. They raise difficult questions. Marshalling all the moving parts described above will be an unprecedented achievement. Practitioners need to hold firm to their vision but flex their methods.

It would, in fact, not be hard to draw the conclusion from the first 20 years that the effort is futile. So I end with my most important message of the entire series: that notwithstanding all the disappointments to date, and the dauntingly tough conundrums that clearly lie ahead, this is not the time to conclude that it’s all too hard and that we should, after all, give up the battle.

There are always tempting arguments suggesting that the struggle is a pointless one. I want to end with some cherished advice given to me early on in my journey by one of the original thinkers in the field, and a personal hero, Robert Klitgaard. He once produced a list of seven arguments anyone in the field will often hear to try to discourage them. For each, he gave a compelling riposte.

Here they are summarised. I share them with the same injunction that clearly inspired him: hold firm, never despair, never give up.

Seven arguments you will hear for not fighting corruption

1. It’s everywhere and you can do nothing about something that’s endemic

But think of health: illness is also everywhere, but we do not conclude that efforts to prevent and reduce ill-health should not be made. Like corruption, illness varies in level and type, and preventive and curative measures can make a difference.

2. Corruption has always existed and always will

Again, a correct observation, but the wrong conclusion. Because a sin or crime exists does not mean opportunities for it cannot be constrained, even if the tendency is persistent.

3. The concept of corruption is vague and culturally determined

Anthropological studies show that people are perfectly capable of distinguishing gifts from bribes. The seminal World Bank study Voices of the Poor of the late 1990s demonstrated this. As we have seen, UNCAC goes a long way now to dispose of these old cultural arguments.

4. Cleansing society of corruption requires a wholesale change of attitudes and values, which can only take place after... [enter some impossible period or change]"

There are ways to close loopholes, create incentives and deterrents, enhance accountability, and improve the rules of the game. The argument starts from the (wrong) premise that the aim is/should be to eradicate, rather than just limit, corruption – but crime is a fixture of human society.

5. In some countries, corruption isn’t harmful – it ‘greases the wheels’ / is a successful coping strategy / provides a safety net

The consensus evidence now (since the mid-1990s) is that corruption overall is a brake on development. There is overwhelming evidence that it disadvantages the poor disproportionately. Arguing that corrupt payments have a function in a given part of the system does not argue for their aggregate desirability (for example, the Indonesia currency collapse of 1998 showed how an external shock was magnified by the corrupt banking practices that had grown up).

6. Nothing can be done if the leader at the top is corrupt or corruption is systemic

It is clearly better for anti-corruption if the leader is leading by example. However, we now see examples of societies saying ‘enough is enough’ – Duvalier; Marcos; the Arab spring; Ukraine. Compared with 20 years ago, much more can now be done to recover stolen assets taken out of a jurisdiction.

7. Worrying about corruption is superfluous – free markets and democracy will gradually make it disappear

This is clearly not borne out by evidence. Elements of free markets and democracy can also drive corruption, particularly when they are poorly regulated (as with competitions for public licenses like mobile telephony or extractive rights). Funding of party politics and elections, meanwhile, has been seen the world over to be a strong driver of corruption.

(Original source of these arguments: Corrupt cities. A practical guide to cure and prevention)

–––––––––

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (this note, final in series)

- The First Cycle, covering Chapters III (Criminalisation/Law Enforcement) and Chapter IV (International Co-operation), began in 2010 and was not completed (for the most part) until 2017. The Second Cycle, covering Chapter II (Prevention) and Chapter V (Asset Recovery), started in 2015 and is ongoing.

- In practice, it turned out in the First Cycle that around two-thirds of reviews did have a site visit. However, this still leaves a significant number of convention parties avoiding them.

- In the First Cycle of reviews, no fewer than half decided not to allow their full report to be released. The largest bloc of ‘transparents’ were from the European Union (EU) and other Western countries. They announced a policy decision during the negotiations that they would all publish their reports in full (as well as committing to always having site visits for their reviews and enabling civil society to be active contributors).

- The assumed explanation afterwards was that the government in question would simply turn to the Chinese to make up the shortfall. Here there would be the added benefit of a ‘no-questions-asked’ approach, in contrast to the Western concern for good governance.