ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

In this series of Practitioner Experience Notes I document the 20-year journey we have made in the UK and globally to address the challenges of corruption to international development. I share my personal experience as a practitioner who was privileged to have been at the helm for most of that time, from the very beginnings of the DFID story, right up to my retirement from the organisation in 2019.

I hope that these articles will serve as stimulus to everyone engaged in the vital endeavour of curbing corruption, and inspire discussion, reflection, and exchange of views.

A historical record – for awareness and understanding

I hope to do three things with these notes. Firstly, to provide that historical record of how things came to be as they are. This background awareness can be vital to one’s understanding, but far too often it quickly fades from organisational memory, leading either to missteps by failing to know the origins of an issue or to laboriously re-inventing a wheel. In most bureaucracies ‘collective memory’ is often extremely shallow, driven by the norm of frequent staff rotation. As one who ‘stayed around’ for nearly two decades on a topic that was constantly evolving, I hope these pieces can provide a bedrock of knowledge, experience, and insight relevant for development practitioners.

DFID’s response to the phenomenon of corruption – addressing the role of domestic departments

Secondly, I hope to illustrate the perspective we developed in DFID of corruption being a phenomenon that requires an entirely different method of response by development agencies than the one our agencies normally adopt. We pioneered in DFID the concept that a proper response required us to look inward at what role other departments of the UK government needed to play on what we dubbed the ‘supply side’ of corruption. This concept includes our companies bribing for contracts and our banks readily taking corruptly-acquired funds from developing countries. Therefore, looking inward became as important as looking outward to developing countries, our usual partners. Our strategy of focusing on domestic departments transformed the nature of DFID’s work, and set an example for other bilateral agencies to follow.

Sharing development practice lessons… The need to stay nimble

Thirdly, I hope to pass on lessons we learned along the way and offer pointers for possible future directions. A key one that I often reflect upon is how development practice has evolved in recent years (perhaps only in DFID but you can tell me otherwise) to have an obsession with planning. All the details to the minutest degree are put in place at the outset, the ‘theory of change’ is tested to destruction, and targets and milestones are set years in advance – almost always projecting a neat linear upward trajectory of progress. In addition, quantifiable ‘value-for-money’ estimates are affixed for our outcomes. None of this would have served our anti-corruption journey well.

The anti-corruption path I will be describing has been a trek informed not by any elegant, pre-conceived roadmap, but by a relentless sequence of incremental steps. These small steps were often opportunistic responses to shifting political and policy interests of political leaders, NGO pressure, or global opinion. We succeeded in exploiting openings wherever we could because our work was fixed by a vision of an ultimate goal of combating corruption wherever we could. Opportunism was our guiding star – exploiting windows that suddenly open up for a short while. I worry we are heading in the opposite direction and losing that nimbleness and flexibility that defined our early approach.

Aid modalities determined the corruption concern

It may come as a surprise to many that development agencies like DFID only became concerned about corruption as recently as the late 1990s. Virtually all thinking about corruption and development has occurred in the last 25 years, despite these agencies having been deeply involved in running programmes in corrupt countries around the world for decades.

Why? – It was not as if it was a sudden new phenomenon: corruption has been around since the first moment humans created organised societies 5,000 years ago. So how could donors ignore it?

It largely has to do with the model of aid provision that was standard up to that time. Donors tended to focus their assistance on funding practical service delivery – health, education, water, agricultural extension. Along came armies of expatriate officers to manage funds and be in charge of operations. By taking firm control of matters themselves, they effectively immunised aid programmes from the rampant corruption in the local system.

A typical programme of the 1970s or 80s would be for a donor to carve out some districts, take on responsibility for the delivery of a service for a number of years, and manage the required procurement, payments of staff salaries, and financial accounting completely separately from national systems. Corruption could be prevalent beyond the confines of the project, but the way donors managed things it did not need to intrude within.

Hermetically sealing development projects from their local environments served to protect donor funding. Every pound, dollar or franc could be accounted for. For donors, corruption became something like wallpaper: always visible in the background but conveniently ignorable by having no direct consequences for your ability to operate. Two things happened in the late 1990s to change this for DFID.

1997: Clare Short’s new, ambitious development approach

The arrival in May 1997 of Clare Short as the first UK Secretary of State for International Development signalled a fundamental break with the past. Short’s view was that aid as it then was, was going nowhere. The ‘little projects all over the place’ might help the individuals lucky enough to benefit, but were not changing the fundamentals of government competence anywhere. Aid simply tended to be substituting for the inability of a government to organise itself properly. The consequences were clear: people would benefit from aid only so long as the aid continued. Once project funding stopped, things would go back to as they were before since nothing was being done to improve the wider national system.

So, in 1997, the old practices were to be replaced by much higher and broader ambitions. DFID would now seek to help shift the fundamentals in a country, reform the entire health system for example, not just treat the symptoms of failure by picking up a few districts for a few years. Benefits would now be possible for the entire country, not just a select few citizens who happened to enjoy the fruits of a donor’s short-term presence somewhere on the ground. As a result, the UK’s aid effort was rebranded – now determined to promote international development, not just aid administration, as DFID’s predecessor – the Overseas Development Administration (ODA) – had been seen to confine itself to.

The birth of UK’s hallmark dual anti-corruption approach

The implications of this were profound for our ways of working. Global donor theology embarked on a trend towards targeting national systems. Moving to what became termed ‘budget aid’ – putting funds into the central government pot, and trusting national accountability systems to manage the finances – rather than deliver and oversee specific services ourselves. And, immediately, this brought the spectre of corruption into play.

It was almost certainly a sensible call in developmental terms. Short herself said we would be running our projects in countries for decades into the future without changing the overall system if we continued with the old way. She wanted countries to be helped to escape from the need for aid. But the consequence, which Short was admirably willing to embrace, was that suddenly corruption became a factor we had to begin to worry about.

So came the second big change for DFID – the birth of an anti-corruption mission, from scratch. This was pretty virgin territory for any donor, but came naturally to Short. Her own personal proclivities gave us an unprecedented platform. She detested the idea of the UK actually contributing to global corruption by allowing our companies to bribe for contracts in developing countries. Neither was it acceptable that our banks (along with our offshore financial centres in the Crown Dependencies and the Overseas Territories) seemed to be readily enabling corrupt elites to extract funds out of the very countries we were giving aid to help develop.

A visit to an African country in the early months led to her realisation that more money was coming out of the place than we collectively as donors were putting in. And the UK was a major player on this ‘supply side’ of the corruption equation. DFID’s anti-corruption work was, from the outset, destined to be radically different to the emerging norm. We would not just seek to help corrupt countries sort themselves out by helping to strengthen their own systems, but strive at home to change attitudes and practices that had long prevailed.

This dual perspective has become the hallmark of UK’s approach to anti-corruption. Other articles in in this series will explain that journey in detail.

Breaking the corruption taboo – a radical redefinition of global norms

But just as Clare Short had a strongly personal mission, she was also a symptom of the changing international mood. Why was the period of the late 1990s so fruitful for anti-corruption globally?

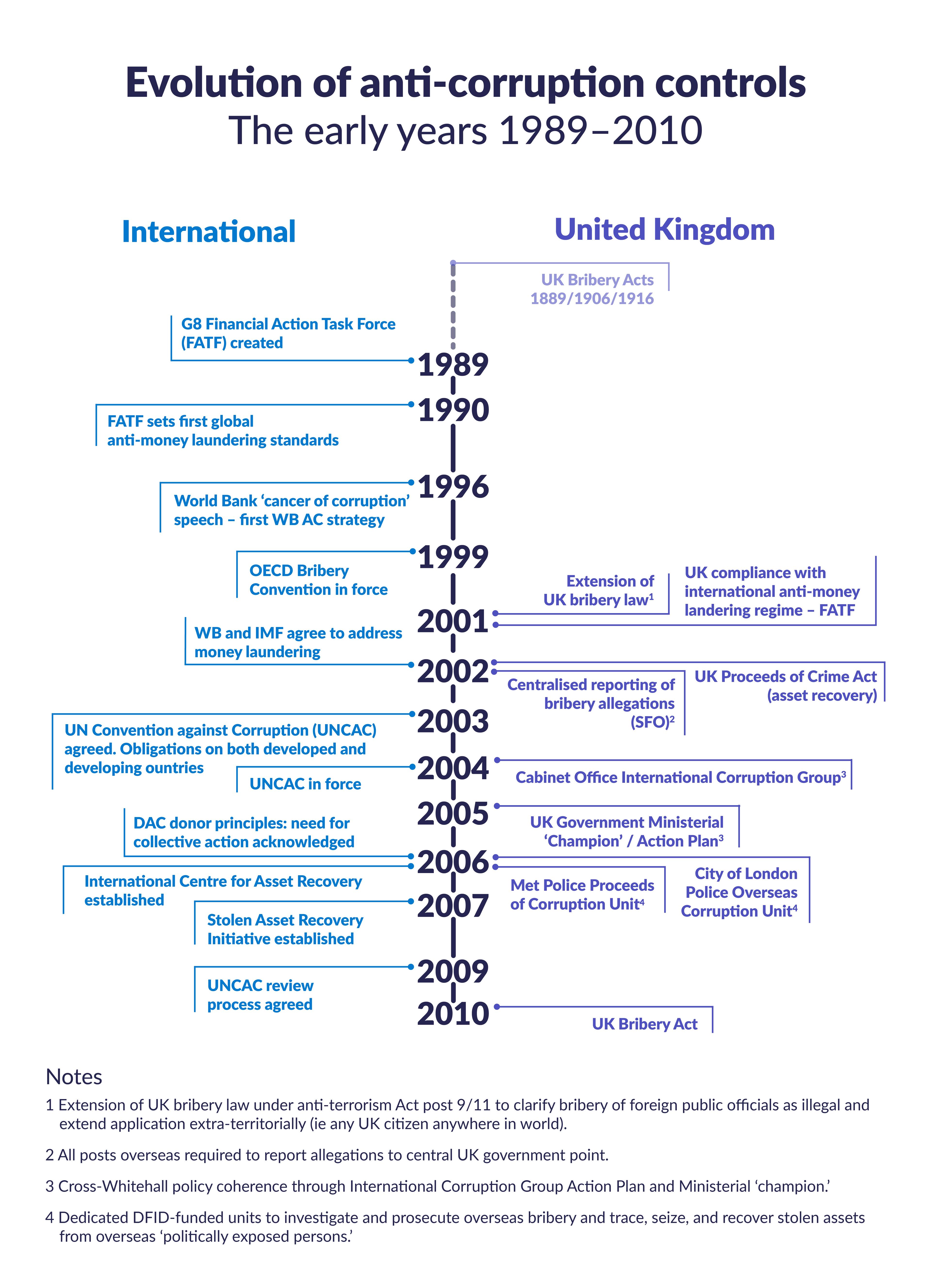

The timeline below shows the burst of activity that occurred in the ten years after the celebrated 1996 ‘cancer of corruption’ speech by the World Bank President, Jim Wolfensohn, which broke a taboo in arguably the world’s most influential development institution. Until that moment, the ‘c-word’ was unmentionable. It was said to be too ‘political,’ too sensitive an issue to bring up with member governments.

Within just a decade of Wolfensohn’s speech, the global mood had radically shifted. All of the most developed industrial economies had agreed legally binding prohibitions on commercial bribery and a tough peer review process. Through the 2005 UN Convention against Corruption – the international community had agreed the first truly global consensus on anti-corruption. In addition, crucial new international bodies had been added to the international architecture to help deal with the relatively novel issue of asset recovery and return.

Arguably, there has never been another decade like it for such radical redefinition of global norms and expectations. For the UK, too – spurred by Clare Short’s energy – the period was a similar one of profound change.

Those of us in the anti-corruption world who saw things right at the beginning have frequently pondered the origins of this surge. What follows is a personal viewpoint. Others may well have alternative theories. The implications of these thoughts are still relevant today.

The driving forces: Knowledge, solutions, confidence, and no more tolerance

I maintain there were four major driving forces that reinforced each other in this period to make the climate highly charged and conducive to change.

Knowledge

A body of research evidence was coming together which showed in compelling terms the damage that corruption causes. This knowledge exploded the prevailing and comfortable myth that corruption greased wheels and kept things moving. No, the evidence was now only too clear that corruption is not grease but grit. It is grit in the engine of the nation, which – if not tackled – accumulates until eventually the engine stops working.

The macroeconomic effects of corruption are profound. The World Bank estimated that it halved inward investment rates, held back growth and increased inequalities. In all, it accentuated and perpetuated poverty.

Civil society had also played a huge role in generating this data. It was largely civil society, and organisations like Transparency International (founded in 1993, intriguingly by an ex-World Bank official who left the organisation out of frustration at its ‘hands off’ policy on the issue21d8c7627782), which began producing the hard evidence. This happened long before governments and multilaterals took notice, and TI’s pioneering efforts were crucial to changing that whole mindset about the effects of corruption.

The emergence of solutions

Ideas and experiences with real, practical, and workable solutions to corruption problems emerged. Again, civil society took the lead. Imaginative approaches from civil society organisations started to create a body of experience in tackling corruption. Seminal documents like the TI source book began to give practical guidance. That book is one of my cherished possessions – it came out in 2000 and is still highly relevant.

I have often remarked to TI that they cleverly never allowed governments to argue that a corruption problem was ‘too difficult.’ TI could always – it seemed – point to an example somewhere in the world where a way of working had been found by a TI Chapter. It never gave us governments the wriggle room to say we couldn’t act. It marks TI out from many other NGOs who merely shout that a problem needs attention. Providing solutions alongside advocacy creates a powerful force for action.

This gave rise, in my view, to the third force:

Confidence

The spirit of the time included a growing sense that something could be done. There was no longer a gloomy sense of inevitability, or hopelessness that the challenge could not be met. Instead, there was a new belief that it was possible to tackle corruption. And again, it has often been the efforts of civil society in difficult places that have demonstrated in practical ways that progress can be made.

No more tolerance

The final factor was an increasing consensus that corruption should no longer be tolerated.

Some high-profile cases of the worst excesses of corruption – Mobutu, Duvalier, Marcos, Abacha – stirred all consciences. The end of the Cold War in the early 90s shifted the global tectonic plates. There was no longer the perceived need by major powers to prop up openly corrupt regimes in the developing and emerging world for geopolitical reasons.

Globalisation also helped to increase awareness of conditions across continents. Modern media, especially news channels and investigative efforts, brought home to many people the contrasts between dire conditions in many developing countries and the illicit riches of their political leaders that found their way to safe havens abroad – often in Europe, the Caribbean, and the US.

Growing democratic trends in developing countries were leading citizens to have higher expectations of their leaders. In the developed world, too, taxpayers were demanding better accountability for the use of aid. They were appalled that their financial systems were playing host to billions of dollars of resources appropriated from developing countries’ treasuries.

On both sides, then, there was an increasing sense of non-tolerance of corruption. Here, too, civil society groups in both developing and developed countries played a major role in publicising cases of corruption and raising the public temperature.

Core lessons from a pivotal period – politics, pressure, and persistence

In the next two parts I will explore in more depth the journey we made, and the lessons we learned, as DFID embarked on its effort to mould a new attitude at home to the UK’s role in international corruption. I will also cover the background to the evolution of the new global framework, which has exploded from almost nothing. Many of these stories still have relevance to the live issues we continue to struggle with today.

But these earliest years also contain some core lessons worth highlighting. Looking back across to the very beginning, I see some crucial pointers that were already clear then – but have perhaps not been internalised as well as they could have. They are as important today as they were then.

Politics matter

It is clear we would not have progressed as far and as fast as we did in DFID without the political leadership coming from the top. Clare Short was willing to confront some powerful resistors and wear them down. That was her nature. We were, perhaps, lucky.

It is noticeable that the other period where, arguably, the UK has made most rapid progress on corruption was Prime Minister David Cameron’s push in 2013–16. These years saw him cajole a hesitant Whitehall into creating the world’s first public register of beneficial ownership, bring about radical changes to the way corruption policy is managed centrally with the creation of the Joint Anti-Corruption Unit as a cohering body at the heart of government, and holding the Anti-Corruption Summit in 2016, which spawned a raft of UK and global initiatives.

These were strong political actions. They made a critical difference to the pace of change in those times and places. But what is also obvious is that they were transient moments. Around the world there are many examples of brave individual leadership, often driven by personal conviction, and also often flaming out all too quickly. Waiting for the arrival of political leaders who ‘see the light’ will always be an uncertain strategy. It is not a good basis for sustained change.

Politics need to be embraced more astutely. A favourite mantra that has stayed with me for many years came from one of my ministers to whom we were laying out the logic of a new corruption activity – involving generating better information and stronger facts to convince leaders to change. The minister was far from convinced. “Phil”, he said, “you have to understand us politicians. We change our behaviour not because we see the light, but because we feel the heat.”

In this one sentence lies a world of insight, and a world of difference between how we as bureaucratic and technical operators think and how politicians think. We have still to reflect this in our ways of working.

Pressure counts … from the outside

It is no coincidence that many of the factors that seem to have driven the global impetus in the mid-1990s stemmed from outside pressure on governments to act: civil society creating noise about corruption and pushing for solutions, media awareness and governments embarrassed by being shown to be propping up corrupt elites, and hosting their ill-gotten gains in our banks. In the UK’s case, the relentless negative reviews of our bribery laws by the OECD drove change.

This is a theme I’ll return to time and again in this series, as too often I have seen development agencies lapsing into their comfortable, technical responses – as if corruption is something that can be trained out of people.

Opportunism and flexibility must go together

A characteristic of tackling corruption is that one never quite knows where and when a ‘moment’ will open up. Big anti-corruption episodes have rarely been foreseeable – think of ex-President Chiluba in Zambia when his successor unexpectedly chose to prosecute him (2003), the Arab Spring (2011), and the fall of Yanukovych in Ukraine (2014).

This calls for donors to be highly flexible in their ways of working and able to respond to urgent needs. Worryingly, that looks increasingly conflicting with current practices. Donors seem much less able these days to react quickly – an issue I’ll explore in a later part.

Persistence is everything … even when things seem to be going nowhere

The lasting lesson is to persevere. I have reflected elsewhere how “every day of my time in DFID working to advance our anti-corruption agenda had the feeling of trying to push water uphill – nothing ever quite looking to be going anywhere; every avenue fraught with resistance; everyone telling me I was on a hopeless mission.”

Looking back to those early starting points, what strikes me now is how much we actually changed things, how far the world has come, despite that daily sense of futility.

The slow, incremental shifts in policy, attitudes and structures only come shining through when you look at the landscape from a decent perspective of time.

–––––––––––––

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off (this PEN)

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

- This is a great interview with Peter Eigen giving a flavour of life at the Bank in the early 1990s.