Blog

Supporting anti-corruption in health – even while global health funding suffers

Corruption hampers health systems’ ability to provide quality, accessible, affordable, and acceptable healthcare for everyone, hindering progress towards universal health coverage. It diverts vital resources from a health system’s core functions: safe procurement, workforce capacity, community infrastructure, and effective health data management. Ultimately, corruption represents a menace to people’s health and well-being, undermining countries’ ability to develop sustainably.

There has been extensive research on corruption’s impact on the health sector. Scholars have found that corruption has contributed indirectly to child mortality, increased anti-microbial resistance, and a slower reduction of AIDS deaths. Most recently, corruption was proven to exacerbate and prolong the Covid-19 pandemic, having an acute impact on marginalised groups, such as women.

Yet, since the end of the pandemic, global health aid – which also funds anti-corruption efforts in this sector – has declined considerably. Health funding is now at its lowest level in 15 years. According to the OECD, bilateral official development assistance for health is projected to decline by 19–33% in 2025. Recent reductions in US global health funding have already led to the closure of major sexual and reproductive health programmes, significant cuts to good governance initiatives, and the weakening of multilateral health agencies’ work on disease surveillance and response.

As resources become increasingly constrained, addressing corruption in the health sector becomes even more critical.

With the clear fragmentation of the global health infrastructure, some questions remain: how well has the global health community addressed corruption risks, and can anti-corruption still be prioritised in this space?

Donor efforts to fight corruption remain uneven

Since 2023, U4 has partnered with Transparency International Global Health to examine whether and how bilateral and multilateral agencies integrate anti-corruption into their health programmatic work. Together, we published Closing the donor gap on health corruption, and presented its findings at the World Health Summit.

The findings were striking. While corruption costs global health an estimated US$560 billion annually, our analysis of data from the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) revealed that only around US$430 million was directed toward anti-corruption activities in health between 2003 and 2024, though this is likely to be an underestimate due to gaps in reporting. Even so, it underscores a pervasive problem: resources lost to corruption vastly exceed the resources the global health community invests in preventing it.

Equally concerning is the limited integration of anti-corruption into most donors’ health and development strategies. Current interventions tend towards the extremes: either broad governance reforms or narrowly targeted initiatives, with few comprehensive medium- or long-term programmes addressing corruption in health. Even when anti-corruption is identified as a strategic priority, several barriers hinder implementation. The political sensitivity of corruption, the low prioritisation of the issue by partner governments, and a perceived lack of evidence linking anti-corruption efforts to improved health outcomes all contribute to inconsistent engagement.

Political caution also undermines multilateral agencies’ and international financial institutions’ engagement with anti-corruption in their health work. Their approaches usually follow a politically neutral framing, with only a handful of organisations strategically engaging in anti-corruption. Most only focus on safeguarding their own funds rather than undertaking direct, programmatic anti-corruption work.

Overall, our research found that donor funding and strategic focus on the issue remain critically low.

The World Health Summit advanced dialogue on donor collaboration

On 12 October 2025, U4 and Transparency International Global Health organised a side event at the World Health Summit to discuss our findings. The Summit brought together leaders from policy, science, the private sector, and civil society, offering a unique platform to discuss how anti-corruption in health can foster cohesion in a time of fragmentation. We invited representatives from Norad, Gavi, BMZ, and the Global Fund to explore how to move forward collectively on this issue.

Our study found that each of these agencies has different approaches to anti-corruption in health: while Norad integrates anti-corruption commitments into its health sector programmatic work, BMZ takes anti-corruption and health as separate priorities. Meanwhile, the Global Fund and Gavi tend to focus more on addressing fiduciary risks. Bringing them together enriched the discussion with different perspectives.

Early in the discussion, everyone agreed that bilateral and multilateral agencies should continue to collaborate to enhance anti-corruption efforts within health. To this end, it was noted that bilateral agencies can exert significant influence through multilateral boards. The establishment of the Global Fund’s Office of the Inspector General attests to this, as its creation resulted from Norad and other bilateral agencies’ strategic advocacy for improved safeguards and oversight functions.

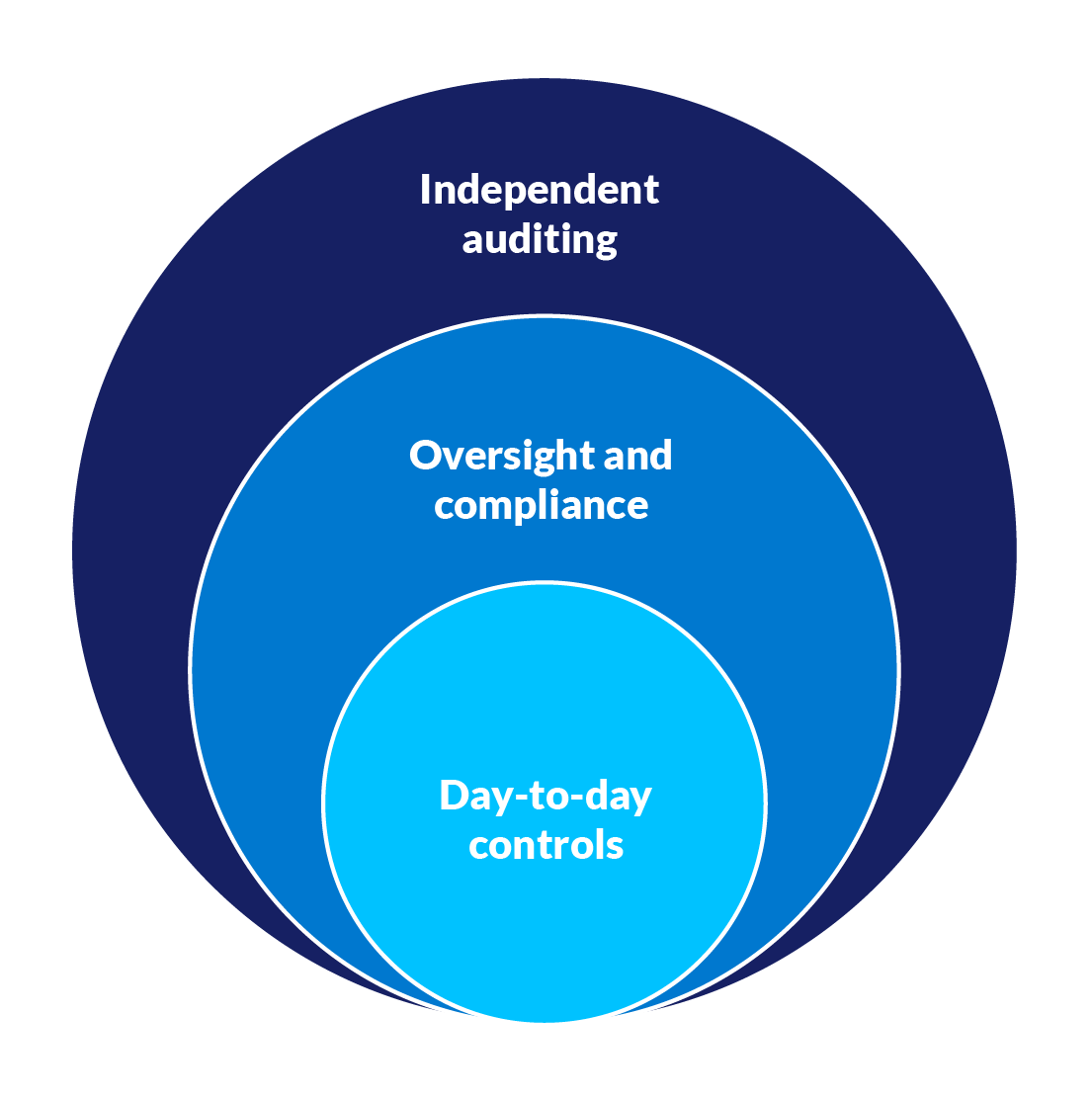

Second, multilateral health agencies such as Gavi and the Global Fund shared the key steps they have taken to reduce fragmentation in global health governance. Both apply the ‘three lines of defence’ model, which divides risk management across day-to-day controls, oversight and compliance, and independent auditing. This structure helps ensure consistent and transparent risk management throughout the grant cycle, under the supervision of their boards.

Three layers of risk management

Multilateral health agencies such as Gavi and the Global Fund apply the ‘three lines of defence’ model to risk. This structure helps ensure consistent and transparent risk management throughout the grant cycle, under the supervision of their boards.

In our panel discussion, it became clear that Gavi and the Global Fund often coordinate this approach in countries where they operate jointly, aligning strategies to improve efficiency and collective impact. A recent example is their partnership with the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) to support low- and middle-income countries in strengthening their public finance management systems, so they can enhance their planning, tracking, and reporting of health spending. This collaboration aims to promote transparency, accountability, and ultimately, greater donor coherence in the use of public funds for health.

Trust as a catalyst for reducing fragmentation

While there are outstanding initiatives mainstreaming anti-corruption efforts in health, most focus on fiduciary controls. In health programmatic work, however, our study found that anti-corruption is rarely a priority. Since bilateral and multilateral agencies still operate under the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, partner governments are still the ones in the driving seat when it comes to setting priorities. Yet, requests from governments for addressing corruption as a development issue within the health sector are still uncommon.

All four agencies who were present at our World Health Summit discussion agree that working with implementing partners who are willing to address corruption facilitates engagement and enhances trust. When partners acknowledge and manage corruption risks of all types, agencies view this as a strong signal of commitment, integrity, and a higher likelihood of achieving meaningful impact with available resources. By contrast, withholding information about wrongdoing out of fear of losing funds can generate suspicion, especially given the known prevalence of corruption risks.

In an increasingly fragmented global health landscape, trust emerges as the most powerful catalyst for securing collaboration on anti-corruption. Anti-corruption does not weaken partnerships; it strengthens them by aligning incentives and fostering mutual responsibility. When trust exists between bilateral and multilateral donors on one side and implementing partners on the other, it creates space for honest reporting, shared learning, and coordinated action against corruption in the health sector.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)