The global health sector faces widespread corruption. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that 45% of citizens globally consider their health sector to be corrupt or extremely corrupt.149903f334ab Where funds and resources are diverted, this undermines the effectiveness, quality, and accessibility of healthcare. Lack of transparency also provides fertile ground for inefficiency and abuse. Corruption often deepens existing inequities, with women and marginalised groups disproportionately affected when, for example, they face demands for informal payments to access maternal health or other essential services.6e7af7bdb02f

Yet there appears to be relatively little action from bilateral and multilateral development agencies to address corruption within the health sector. This U4 Brief collects evidence from an upcoming report authored by Transparency International Global Health, which seeks to understand this gap. The research shows that interventions tend to be broad governance reforms or specific, targeted initiatives. Few comprehensive medium- or long-term programmes address the topic.

The brief outlines the report’s main findings across bilateral and multilateral engagement in anti-corruption mainstreaming in the health sector. It also highlights some challenges faced by agencies in addressing corruption directly, along with opportunities for action. It then concludes with recommendations for development agencies and their partners to increase action on this critical issue. For bilateral donors, these include fostering collaboration between health and anti-corruption teams within agencies, strengthening engagement with country missions, improving transparency and data reporting, and pushing for safeguards through multilateral boards. For multilateral agencies, the brief recommends integrating corruption risk analysis into country programmes, supporting improvements to public financial management and procurement systems, and issuing practical guidance such as technical briefs to help countries strengthen transparency and accountability in health programmatic work.

Key findings

The report’s funding analysis of International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data uncovered that bilateral donors mainly commission small, targeted projects working to address anti-corruption, transparency, and accountability (ACTA) in health, while also providing larger funding to broad health or governance programmes where anti-corruption is just one objective. Meanwhile, the strategy analysis found that bilateral donors’ approaches fit into one of three categories: first, those countries that fully integrate ACTA into sectoral approaches; second, where anti-corruption and health are considered as separate development priorities; and third, donors with no explicit focus on either health or ACTA. For multilateral donors, the analyses found low levels of integration of ACTA into health as part of their strategies. This was with the exception of the World Health Organization12b32881e397 and Inter-American Development Bank.ce3331c56931

Bilateral donors appear to fund few projects on anti-corruption in health

The analysis of bilateral donors’ funding revealed three types of funding where both health and anti-corruption were included in the IATI data: broad aid activities with some focus on health and ACTA; specific ACTA-in-health projects implemented by any partner, such as a civil society organisation or a UN agency on behalf of a donor; and contributions made to the central budget of a UN agency where the overall funding agreement refers to ACTA priorities.

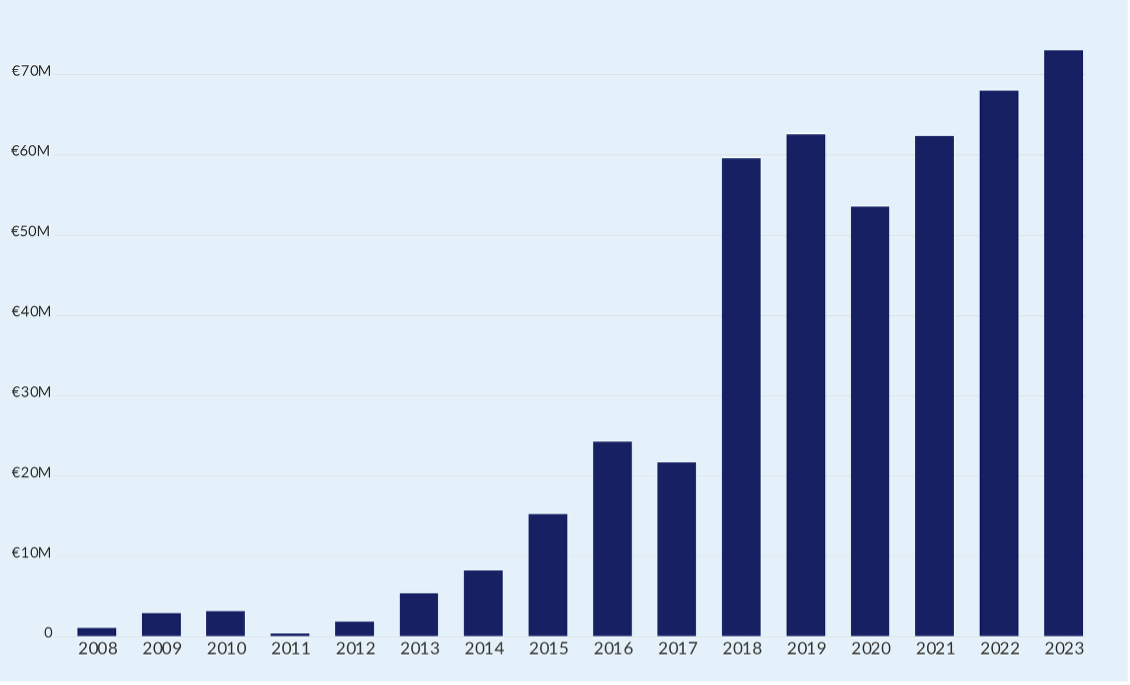

The analysis found comparatively low numbers of projects and activities by donors in this area – 430 million euros worth of activities commissioned on ACTA in health over a 21-year period between 2003 and 2024. However, this figure is likely to be an underestimate, as some donors’ data had missing elements that would have allowed a full analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Annual expenditure from on ACTA and Health

The largest recipients of funding for work on ACTA in the health sector were found to be multilateral agencies – although the way core funding contributions are categorised and methods of reporting are both likely to have increased this proportion in the data. For instance, significant core support from the Danish Development Agency (Danida) to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and UN Women references terms like ‘corruption’ in the funding description. This means they are captured by the keyword search, even if specific anti-corruption work in health is not the primary focus of the funding. Multilateral agencies also seem to report when they move funding from one UN entity to another, which increases the proportion of expenditure recorded as flowing to multilateral agencies.

Overall, the data suggest that donors mainly use a dual approach: commissioning smaller, targeted projects that explicitly work towards ACTA in health, while also providing much larger amounts to broad health or governance programmes where anti-corruption is just one of several objectives. An important question this raises is whether ACTA objectives become diluted or are effectively integrated within these larger programmes.

Bilateral donors engage differently depending on their strategies

Bilateral donor approaches fit into one of three categories. The first category covers those countries that fully integrate ACTA into sectoral approaches. For example, Norway, Sweden, and the US80d6c1d294d2 connect anti-corruption efforts to the health sector in this way. The second category is where anti-corruption and health are considered as separate development priorities. Canada, Germany, and the UK take this approach. The third category comprises donors with no explicit focus on either health or ACTA. Denmark, the European Union, Finland, and Switzerland fit into this category.

Category one donors (Norway, Sweden, and the US), which fully mainstream ACTA into health sector support, do so in slightly different ways. For Norway, the country’s government-wide development policy considers anti-corruption to be a cross-cutting issue across its entire development portfolio.18af45fe2aa7 In terms of funding, the country supports global-level, norm-setting initiatives. Sweden’s new development policy, global health policy, and its strategy for sexual and reproductive health, meanwhile, all make specific reference to the need to address corruption in the health sector, in part to ensure sustainable health financing.b448fe2acf9d In terms of funding, the country provides smaller, bottom-up grants to civil society.

In terms of its strategic approach, the US under Biden sought to institutionalise anti-corruption across US development efforts. This included the US Agency for International Development publishing guidance on integrating anti-corruption into health sector programming.25c6da01d2fd The US also primarily funded large, top-down governance projects implemented by commercial consulting firms. These distinct patterns suggest different potential patterns of theories of change: the USA focuses on top-down institutional reform, Sweden on bottom-up civil society accountability, and Norway on building global norms and networks.

For category two donors, the strategy reviews found Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom consider both health and anti-corruption to be development cooperation priorities.e92239f1441d However, none of the three countries appears to integrate anti-corruption into their health sector strategies. Canada’s development policy,3202ac4b5d7e for example, does not refer to addressing corruption, but talks more broadly about the need to strengthen the rule of law. Germany’s health policy makes broad reference to supporting sustainable health financing systems and the need to tackle corruption in the sector. Yet it does not go into detail on how it intends to do this.0723f05e612d The United Kingdom, meanwhile, makes explicit reference to addressing corruption in its 2023 development white paper;a273486bb0c3 however, there is no discussion in the paper around the need to address corruption within sectors.

In terms of funding, category two donors’ funding data reveal a more complex reality. The IATI records show that all three countries have funded specific anti-corruption actions in health projects. This suggests that while there is no systemic, internally driven policy for sectoral integration, these donors are willing to engage on the issue from time to time – often by channelling support through expert external partners like civil society organisations and multilateral agencies.

Category three countries all have slightly different strategic approaches. Denmark’s development strategy considers anti-corruption measures through governance support but there is no mention of integrating these into health systems strengthening. Finland’s development strategy does not appear to work specifically towards health outcomes nor does it mention anti-corruption.00dde109a6ca The EU’s Global Health Strategy, meanwhile, does not call for the integration of anti-corruption measures, although it does mention increasing transparency in health commodity markets and supply chains.aa9222185ee4 The development policy analysed for Switzerland, which ended in 2024,0c661a608c22 considered anti-corruption under a sub-objective of good governance. However, no sector-specific approaches were considered.

The lack of explicit strategic integration is reflected in the funding patterns of these donors, which often show indirect or fragmented support for ACTA in health. For example, Denmark appears to have provided significant funding for activities marked as health and anti-corruption. However, the figure comprises core funding disbursements to UN agencies with no anti-corruption objectives attached. Finland’s funding pattern aligns with its strategic priority of strengthening civil society. Most of Swizerland’s funding, meanwhile, is channelled through multilateral partners like the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for broad ‘strengthened local governance’ programmes or provided as direct support to civil society,

A clear pattern emerged from the analysis of the bilateral donors: that is, a donor’s official strategy is the single most important factor determining its capacity and willingness to act on health sector corruption. The report found that without a formal strategy integrating ACTA into health, the issue is consistently sidelined. For donors with fully integrated approaches (Norway, Sweden, USA), the strategic mandate fosters collaboration between internal health and anti-corruption teams, enabling concerted action on the global stage.For all other donors, this internal synergy was found to be absent.

Most multilateral donors engage with anti-corruption and health less strategically

The U4 Report also reviewed the strategies of major global health initiatives, along with those of multilateral agencies and international financial institutions (IFIs) working in the health sector.The analyses found overall low levels of integration of ACTA into health, with three distinct patterns: a small group that explicitly integrates ACTA into health work; a second group that focuses on accountability and fiduciary safeguards; and a large group that prioritises health but lacks an explicit ACTA focus.

The first group only comprises the World Health Organizationf70edee7a4ea and Inter-American Development Bank,b110ab9d27be which do explicitly refer to mainstreaming ACTA into the health sector in strategy documents. The IADB Health Sector Framework is the most comprehensive, recognising corruption as a big contributor to low productivity and suboptimal quality of health services.6285012c25a6 Meanwhile, the WHO’s draft 2025–28 programme of work includes addressing corruption as an outcome of strengthening primary care approaches.cb71264e44c9

A second group, including the Global Fund for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malariaf7c3fe380ca9 and GAVI (the Vaccine Alliance),e956fd4c9bac has invested in mechanisms to address fiduciary risks, safeguarding funds against corruption and misuse.

The third group comprises the largest group of multilateral institutions and financing banks, which prioritise health but do not explicitly integrate anti-corruption into their strategies. Instead, they often use broader, more politically neutral terms like ‘governance’, ‘accountability’, and ‘efficiency’. For example, despite no explicit recognition of corruption, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and UN agencies such as UNICEF and UNFPA have recognised the role of accountability in health. In practice, it is important to recognise that the World Bankf02e71251dec has also supported public financial management (PFM) reforms and procurement systems strengthening. Moreover, anti-corruption approaches by UN agencies are more likely to be technical in nature, recognising the UN’s role in supporting its member states to attain their development aims in their own capacity.

Overall, the research found that multilateral agency approaches are shaped by their institutional mandates. This usually results in politically neutral framing, with few organisations explicitly integrating ACTA into their health strategies. Instead, they work towards safeguarding their own funds rather than undertaking direct, programmatic anti-corruption work.

Significant barriers limit action

Even where there was a strategy explicitly integrating anti-corruption into the health sector, significant barriers limit the translation of high-level policy into consistent action at the country level.

One issue is that most work on anti-corruption is driven by headquarters, not country missions. According to several informants, headquarters personnel often see ACTA as a higher priority than their colleagues working locally, who are more concerned with immediate operational demands. Headquarters personnel, meanwhile, seldom have much influence on the design of programmes, which are often initiated by government partners. If partners do not bring ACTA onto the agenda, then the topic is not engaged with. At the same time, country missions may lack the necessary knowledge, capacity, and autonomy to act on the topic.

Donors also mentioned that anti-corruption was generally not included due to a lack of evidence on the impact of accountability and transparency on health outcomes. Lack of data making a clear link between investment in transparency measures and improvements in health outcomes was given as a reason for investments not being prioritised. This was particularly the case where there were competing demands for support.

Key informants reported that recipient governments rarely requested support specifically for anti-corruption in the health sector. The principle of national ownership, which is central to the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness,6046a03cc444 requires donors to align support with partner government priorities. So, if the assistance is not explicitly requested, it cannot be easily prioritised in donor support.

Interviewees also revealed a strong sense of political caution. They mentioned facing increasing domestic pressure on development aid budgets. They expressed a clear concern that openly funding ‘anti-corruption’ projects could be framed negatively by the media or political opponents, fuelling arguments that aid money is being misused and should be cut.

Several respondents raised issues of transparency and accountability of UN agencies, many of which receive bilateral donor funding to support anti-corruption and health initiatives (as is the case with Denmark and Switzerland – see discussion of category three countries in section on bilateral donors above). Respondents felt that the UN system did not always do enough to respond to internal allegations of corruption within the system itself. Respondents considered that this constrained the ability of the UN system to be an effective vehicle to champion reforms within health systems.

Several respondents from multilateral agencies highlighted the need for their institutions to remain clear of engaging in domestic political issues in countries where they work, instead maintaining a role as neutral assistance partners. They observed that multilateral agencies, as technical and financing partners, are careful about the parameters of their engagement. A central theme from interviews with multilateral staff was the imperative to remain politically neutral. Consequently, they are often reluctant to use the term ‘corruption’ explicitly, as it can be perceived as ‘labelling’ or interfering in a country’s sensitive domestic affairs.

Opportunities exist to better mainstream anti-corruption in health

Despite the barriers at the country level, interviewees pointed to a promising strategy for making progress: closer integration and collaboration between their internal health and anti-corruption teams. Respondents cited this internal alignment as a major success factor. It enables more effective, collective action on the international stage, which in turn creates opportunities for cooperation with multilateral partners. This collaboration has been found to lead to progress in terms of influencing multilateral agencies’ strategies; sustaining top-down pressure (maintaining ACTA on the agenda of multilateral board meetings); and building partnerships among agencies on the topic.

Faced with the political sensitivities of direct government engagement, donors who treat anti-corruption and health as separate development priorities appear to adopt a pragmatic twin-track approach. The first track involves top-down, institutional pressure, engaging with global bodies to improve anti-corruption safeguards in the health sector. Their goal is to push for institutional change while maintaining political distance. The second track works towards improving accountability at the local level by directly funding civil society organisations.

Interviewees expressed that it is important to approach corruption as a global issue, not one solely concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). As such, many are seeking to mitigate the role of their own nation, and other high-income countries, as enablers and facilitators of transnational corruption. This also takes place within the health sector, where issues of corruption are not always contained within geographical boundaries. For instance, global health supply chains face significant corruption risks due to their transnational nature, with pharmaceutical drugs relying on ingredients from multiple countries, and being processed and packaged across different locations before reaching their final destination.453a85d93050

Even where donors lack strategic prioritisation, support for more interventions to understand the links between corruption and health outcomes will help make the case for corruption to be brought onto the agenda in partner countries. Similarly, donors may also consider bringing national and local anti-corruption organisations into discussions on health sector support. Doing so will help raise prominence of the issue at the national level, bringing the topic onto the agenda, and will create legitimacy for UN agencies funded by them to engage on the topic within countries.

Donors might also consider the lessons learned from prior collective efforts undertaken by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) and other bilateral donors to strengthen safeguards within global health funds against corruption. These donors have used their positions on the board of the GFATM to push for the organisation to put systems in place to better safeguard funding.adc5c84105cd Such reforms have been cited as having been effective in furthering reforms, and donors might like to consider similar approaches to UN bodies.

The report found that donors’ various delivery models provide opportunities to embed ACTA measures. For example, if an agency issues ‘calls for proposals’ where parties can apply to provide a particular health service, it could include technical briefs/guidance notes on integrating ACTA to influence the approach of applications.

Development banks, such as the World Bank and regional development banks, as well as institutions such as the GFATM and GAVI, have clear responsibilities to safeguard funding provided by investors. Institutions have responded to this by strengthening their internal systems and by using local fund agents to provide assurances. By investing in the strengthening of national public financial management systems instead, these institutions could help assure both the security of funding provided by donors and of national budgets.

Multilateral agencies’ ACTA interventions tend to be technical in nature and directed towards addressing specific issues, such as procurement systems strengthening, public financial management reforms, or help with data management systems. These activities can increase transparency and safeguard against corruption. The research observed that such ACTA interventions tend not to be promoted as ‘anti-corruption’ or improving accountability. Instead, they are presented as part of a broader set of interventions that work towards building efficiency and effectiveness, which are more politically salient than corruption.

There is scope for multilateral organisations to support transparency and accountability measures that mitigate against corruption in the health sector by, for example, introducing beneficial ownership registries and open contracting. Top-down approaches – engagement through boards and high-level meetings – can also provide effective ways to ensure ACTA is a priority for multilateral agencies.

Recommendations for bilateral and multilateral agencies

Bilateral donors should address silos

The U4 Report provides several recommendations for bilateral donors. First, they should develop strategies to integrate ACTA measures into the health sector through cross-donor working groups, with countries such as Norway and Sweden sharing their experience of integration. The strategies should be informed by evidence-based research and practical tools provided by organisations such as TI Global Health and U4. Bilateral donors can also work to ensure the recognition of the issue and the need for action in high-level meetings and UN resolutions. This requires building consensus with other member states in order to legitimatise work by UN agencies on the topic. Opportunities to do so in the short term include the upcoming SDG-3 reviews, UN High Level Meetings on health topics, eg, HIV/AIDS, and regional meetings on SDG-3 progress.

To address the issue of corruption being politically sensitive, donors can leverage existing, politically neutral health objectives as entry points to introduce anti-corruption principles. This can be done by framing interventions in terms of efficiency and systems strengthening, such as supporting improvements to public financial management or reforming procurement systems. These actions directly mitigate corruption risks while aligning with accepted goals on health systems strengthening.

Bilateral donors should also improve the quality and consistency of the funding data they provide to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) to enable effective monitoring and accountability. This can be done by donors not only improving their own reporting standards but also contractually obliging all implementing partners and recipients to provide high-quality, disaggregated data as a condition of funding.

In terms of programme implementation, they must engage better with country missions and programmes on ACTA in health. For example, donors who already work on ACTA in health should consider publishing or, if not possible, sharing country assessment reports with other donors in order to increase donor understanding of country situations and opportunities. They can also integrate political analysis more systematically at both the design and implementation stages of projects. Donors should invest in building the capacity of country mission staff through awareness-raising initiatives and practical training delivered by headquarters.

Bilateral donors can work with multilateral agencies to develop safeguards within national systems to further the work of multilateral agencies. These safeguards can help mitigate the risk of fraud in multilateral grants and loans, and support national systems to be more effective and deliver better value for money.

Multilaterals should integrate anti-corruption and transparency into core health strategies

Multilateral agencies should integrate specific, actionable anti-corruption measures into their core strategies and country programming. Institutions like the World Bank, for example, should systematically include a health sector corruption risk analysis in all their country partnership frameworks, while UN agencies should ensure their country cooperation frameworks move from referencing corruption as a general challenge to proposing tangible support for sectoral transparency and accountability. This is a shift that will require dedicated financial support from development partners.

Agencies and financing institutions should also start actively strengthening national systems by investing in public financial management and procurement systems. This approach will not only safeguard their own funds but also enhances the integrity and efficiency of the entire national health budget, aligning with the goals of the Lusaka Agenda.613579d1546b

They should also leverage existing tools to actively promote the integration of ACTA into the programmes they fund. The Global Fund, for example, issues technical briefs that are highly influential in shaping grant applications. It should develop and disseminate a specific technical brief on how to integrate anti-corruption, transparency, and accountability measures into health systems strengthening proposals. Similarly, global health initiatives like GAVI, which acknowledge downstream corruption as a major operational risk, should move from simply identifying this risk to requiring and funding specific mitigation activities within their country grants.

Given their mandate to remain politically neutral, multilateral organisations can proactively use technical language and work towards the outcomes of anti-corruption (efficiency, value etc.) rather than the issue of corruption itself. The research shows a reluctance to engage in topics that could be perceived as political. However, there is significant scope to support technical solutions that increase transparency and mitigate corruption. This includes providing support for the implementation of open contracting in health procurement or establishing beneficial ownership registries for suppliers. Both of these are practical, evidence-based measures that can be framed as improving efficiency and accountability rather than as sensitive political interventions.

Strengthening coalitions and investing in evidence is key to drive anti-corruption in health

Both bilateral donors and multilateral agencies should consider support to anti-corruption coalitions to increase bottom-up pressure for change. For example, when developing country cooperation strategies, donors should consult with civil society organisations working on transparency and accountability to better understand where issues around ACTA lie. In contexts where there is little domestic political appetite to address corruption, development partners should consider developing informal coalitions and collaborations with CSOs and academic institutions to investigate important topics where discreet action is possible.

Both should also invest in research to unlock action on health sector corruption and what works to mitigate it. For instance, they can provide dedicated, flexible funding for foundational research. Bilateral donors should provide UN agencies, academic institutions, and civil society with flexible or core funding specifically for generating evidence on health sector corruption. This is critical because the current trend towards tightly earmarked project funding makes it nearly impossible for agencies to fund the initial research needed to design evidence-based programmes.

They can also treat evidence generation as a strategic investment. This initial support should be seen as seed funding. It will allow partners to identify specific vulnerabilities, test solutions, and build the case for larger, more targeted anti-corruption programmes in the future.

All donors should break down internal silos to foster structured collaboration between their health and anti-corruption teams. The research referenced in this Brief identifies that closer internal integration is a key success factor for donors with a strong track record on ACTA in health. To move from high-level strategy to effective community-level programming, donors must bridge the gap between their health and governance departments. This can be achieved by establishing joint working groups or formal liaison roles for specific high-risk countries or large-scale health programmes; mandating a cross-team review process, where major health investments are formally reviewed by anti-corruption/governance specialists to identify risks and integrate safeguards before they are approved; and by developing joint training for staff at both headquarters and country missions.

They can also leverage technical assistance to mitigate corruption risks. For instance, donors should apply an ‘anti-corruption’ lens when developing technical assistance programmes and consider how they can leverage technical assistance to mitigate against corruption risks. They should also consider including indicators in performance monitoring to allow the impact of such measures to be better quantified. Bilateral and multilateral donors, meanwhile, can consider the inclusion of anti-corruption as a cross-cutting theme or agenda in their programming; while bilateral donors should produce guidance for their country missions and embassies on how to integrate ACTA approaches into the health sector.

As the forthcoming report shows, therefore, to drive meaningful change, the global health community must move beyond general awareness and actively engage with health sector stakeholders to develop and implement practical, context-specific solutions.

Mixed methods research

The research for the report was conducted from October 2023 to November 2024 and used several methods: desk-based strategy reviews (including international development, health, and governance/anti-corruption strategies), International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) analysis,aeefd205b9f5 and key informant interviews with bilateral and multilateral agencies. The aim was to better understand how and where donor and multilateral agencies have been investing in anti-corruption, transparency, and accountability (ACTA) in health.

The authors followed a three-stage process: first, they analysed IATI data to examine historic patterns of bilateral and multilateral funding on ACTA in the health sector. Second, they reviewed policy and strategy documents from ten bilateral donor agencies and nine multilateral agencies to understand the extent to which these agencies prioritise ACTA in their development assistance, and if, and how, they integrate the same into health programmatic work. Lastly, they used the results of these two analyses to conduct semi-structured interviews with representatives from 15 bilateral donors and 7 multilateral agencies between May and October 2024. This enabled the research to assess the strategic focus of donors and multilateral agencies in relation to both anti-corruption and health, and to examine the levels and types of work commissioned or funded on the topic.

- OECD 2017.

- Coleman 2024.

- WHO 2024a.

- IADB 2021

- Strategy reviews and interviews were conducted in 2024, prior to the US presidential elections and reflect US policy up to 2024.

- Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2017.

- Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs 2018; 2022; 2023.

- USAID 2022.

- BMZ 2023b; FCDO 2023; Global Affairs Canada 2017.

- Global Affairs Canada 2017.

- BMZ 2023a.

- Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs 2023.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Finland n.d.

- European Union 2022.

- Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs 2020.

- WHO 2024a.

- IADB 2021.

- Ibid.

- WHO 2024a.

- GAVI n.d.

- GFATM 2021.

- N.d.

- OECD 2005.

- Kohler and Dimancesco 2020; OECD 2024.

- The Global Fund n.d.

- WHO 2024b.

- IATI n.d.