1. Building the infrastructure to combat corruption

Corruption remains a major obstacle to the democratic, economic, and social development of Ukraine. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2020, Ukraine ranked 117 out of 180 countries, with a score of 33 out of 100, making it one of the poorest-performing countries assessed in the report. Excessive delays in trying high-profile corruption cases and limited convictions have long undermined the credibility of the Ukraine government’s commitment to anti-corruption and have fuelled a culture of impunity. The country has struggled to develop an independent, accountable, and transparent judiciary that is respected by the public. Public demand for measures to combat corruption continues to be extremely high.

At the same time, the government of Ukraine has taken several steps to break ties with endemic corruption since the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. These include creating the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU), the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), and the National Agency for Preventing Corruption (NAPC) in 2015, followed by the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) in 2018. The formal launch of the HACC on September 5, 2019, marked a significant milestone in the fight against corruption.

Formation of the HACC was driven by public demand and civil society advocacy. It was the outcome of a series of interventions, including studying lessons learned in other jurisdictions that have set up anti-corruption courts; building consensus among a broad group of stakeholders from the government, judiciary, and civil society; coordinating international donor assistance; and drafting the legal framework to establish the HACC. This process answered key policy questions related to design choices, including the court’s size, place in the judicial hierarchy, mechanisms for selection and removal of judges, scope of jurisdiction, trial and appellate procedures, and relationship with anti-corruption agencies. A recently published study, Ukraine’s High Anti-Corruption Court: Innovation for Impartial Justice, addresses these design and procedural choices, focusing on the role of civil society and the international community in establishing the court and on the special vetting procedures that were applied in selecting judges.

Adoption of legislation is merely the first step in the process of establishing an anti-corruption court, or any specialised court. A series of subsequent actions are required to make the court fully operational and effective so it can perform in line with the high public expectations for it. These include, first and foremost, selecting competent judges and preparing them to take the bench. Other actions include recruiting, hiring, and onboarding qualified court personnel; setting up proper administrative and organisational structures, including adequate courthouse facilities, court security measures, and information technology (IT) infrastructure; and creating effective policies and procedures for communications and public outreach.

An essential factor throughout the process is leadership by a highly coordinated coalition of local civil society organisations, working in tandem with international donor assistance projects. In the case of the HACC, international partners included the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) New Justice Program (USAID New Justice Program, see Box 1); the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Project Coordinator in Ukraine; the European Union Anti-Corruption Initiative (EUACI); and the International Development Law Organization (IDLO), among others. They provided assistance in creating the legal framework for the HACC and building the court’s capacity to sustainably adjudicate high-profile corruption cases through evidence-based programming.

Box 1. USAID New Justice Program

The USAID Nove Pravosuddya Justice Sector Reform Program, or USAID New Justice Program, started implementation in Ukraine in October 2016, with activities continuing through September 2021. The program is designed to support the Judiciary, the Government, the Parliament, the Bar, Law Schools, Civil Society, Media and Citizens to create the conditions for independent, accountable, transparent, and effective justice system that upholds the rule of law and to fight corruption.

The USAID New Justice Program focuses on five main objectives:

- Strengthen judicial independence and self-governance

- Increase accountability and transparency of the judiciary

- Improve the administration of justice

- Raise the quality of legal education to meet the professional requirements of the bar and judiciary

- Expand access to justice and protection of human rights

2. Establishing the High Anti-Corruption Court

The number of specialised anti-corruption courts worldwide has been growing steadily since the first such court was established in the Philippines in 1979. The formation of these courts aims to address problems in the existing legal structure, most often in countries where the judicial system appears unable or unwilling to timely and fairly consider investigated and prosecuted corruption cases. Ukraine’s HACC is the most recent addition to this group of specialised courts. Its origins are in the Revolution of Dignity of November 2013 to February 2014, which resulted in the ouster of then-President Viktor Yanukovych and which revealed very low levels of public trust and confidence in the government and judiciary.

In response to immense public pressure immediately after the Revolution of Dignity, the Parliament (Verkhovna Rada) adopted several pieces of legislation to strengthen judicial accountability. In April 2014, Parliament adopted the Law on Restoring Public Trust in the Judiciary. This law dissolved the highest bodies of judicial self-governance, the High Council of Justice (HCJ) and High Qualifications Commission of Judges (HQCJ), whose members were seen as incapable of holding judges responsible for gross violations of human rights during the peaceful ‘Maidan’ protests (they were later reconstituted with new members). The law further established the Interim Special Commission for Vetting of Judges (ISC), which received 2,192 submissions related to judicial misconduct and ultimately recommended disciplinary measures against 58 judges. The ISC was a temporary measure, and in September 2014 the Parliament adopted the Law on Purification of Government, commonly referred to as the ‘Lustration Law’, which banned high-level public officials and judges from holding or taking office for five to ten years if they had served in the Yanukovych administration and/or made decisions that undermined human rights and rule of law.

These measures unfortunately had limited impact. Only 27 out of 3,000 judges who failed the vetting process were dismissed from the bench. This approach, especially with regard to judges, who have unique status and guarantees of independence, was criticised by the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, which provides states with advice on legal and institutional structures. Four claims were filed by the Supreme Court of Ukraine and 47 opposition Members of Parliament (MPs) at the Constitutional Court of Ukraine (CCU) concerning the constitutionally of the Lustration Law. These have been pending at the CCU since 2015.

Judicial accountability, however, remained high on the agenda, and in February 2015 Parliament adopted the Law on Ensuring the Right to a Fair Trial. This introduced substantive changes to both the Law on the Judiciary and Status of Judges and the Law on the High Council of Justice, as well as to related procedural codes. The new law improved the disciplinary liability of judges and introduced judicial performance evaluation procedures for all judges, to be conducted by the High Qualifications Commission of Judges. The law also improved procedures for appointing members to the High Council of Justice. Nevertheless, the operations of both the HCJ and HQCJ raised questions about the integrity of their members and their ability to hold judges accountable.

Lesson learned

While considering the establishment of anti-corruption courts, look for windows of opportunity created by public attention to the issue. By acting quickly, advocates have a chance to realise bold anti-corruption solutions.

Also in 2015, NABU was established to investigate high-profile corruption cases and SAPO was set up to prosecute them, furthering the development of the anti-corruption infrastructure. Since their creation, the number of such cases pursued has increased significantly. By June 2019, NABU detectives had investigated 745 cases, and by the end of 2018, SAPO prosecutors had submitted 176 cases in court.

However, adjudication of these cases remained sluggish and slow. Convictions were obtained in only 28 cases, mostly based on plea agreements, as noted in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report on anti-corruption reforms in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Most cases ended up going to local district courts, where judges had no specialised knowledge of how to adjudicate complex corruption cases. Most district court judges, moreover, were not prepared for the systematic interference and psychological pressures of handling cases involving high-level public officials in a corrupt environment, and many had lower salaries and fewer security guarantees than the investigators and prosecutors who appeared before them. These courts were overloaded with general cases, leading to delays in considering corruption cases, with some judges appearing to intentionally delay matters to avoid rendering a decision. It was also difficult for local courts to form three-judge panels, as required by amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code, due to the lack of sufficient judges in some courts.

The judiciary’s inability to fully address the challenge of adjudicating high-profile corruption cases, together with perceived political interference in the judiciary, lack of transparency, and ineffective administration of justice, was reflected in public opinion surveys showing that only 10% of the public trusted the courts. According to the judiciary’s own statistics, approximately 11% of local court users and 20% of local court judges acknowledged corruption and bribery within the judicial system. Reforming the judiciary was ranked as a top priority among Ukrainians after corruption, and as the number one concern for foreign investors.

In this environment, Ukrainian civil society started to discuss the possibility of establishing a specialised court to deal with human rights abuses and corruption during the Yanukovych regime and with the criminal cases related to Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and its support for separatists in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. In February 2016, the International Renaissance Foundation proposed a bold concept for establishing a specialised court for corruption, war crimes, crimes against humanity, terrorism, and genocide. This idea was later refined to focus on creating a specialised court for corruption cases to avoid confusion with international human rights and humanitarian law issues.

In the absence of government leadership and inspired by civil society, the international donor community began to consider support for establishing an anti-corruption court in Ukraine. In March 2016, USAID FAIR Justice Project developed a draft concept for creating a court that focused on four key activities: (a) developing the legal and regulatory framework; (b) selecting judges and administrative staff; (c) training judges and administrative staff; and (d) engaging civil society and raising public awareness. Together with the OSCE Project Coordinator, USAID New Justice Program supported a series of regional discussions to raise awareness and foster policy dialogue on options for establishing a specialised anti-corruption court. This included providing policymakers with comparative materials regarding the creation of the Special Court for Organised Crime in Serbia and the Special Court against Corruption and Organised Crime in Albania.

Lesson learned

In adopting anti-corruption court laws, take care to limit opportunities for delays. This includes developing an implementation plan that clearly defines timelines for the establishment of the court.

At the same time, opposition political parties representing a mix of ideologies in Parliament had started to push for the establishment of an anti-corruption court. To gain support from the ruling party, they voted for critical constitutional amendments related to the judiciary in exchange for inclusion of the anti-corruption court in revisions of the Law on the Judiciary and Status of Judges. Using an evidence-based approach, they argued that the court was necessary to complete the process of specialised handling of corruption cases from investigation all the way to adjudication. On June 2, 2016, Parliament approved amendments that first codified the High Anti-Corruption Court in a single provision. From that point, it would take another two years for the Law on the High Anti-Corruption Court to be adopted. This delay resulted in a key lesson learned: when moving to establish an anti-corruption court, set a timeline in law.

Meanwhile, there was no strategy or plan for making the court operational, especially with respect to financing and infrastructure. In November 2016, USAID through its USAID New Justice Program supported a study visit to Slovakia to learn about the establishment of that country’s Specialized Crimes Court (SCC). The delegation included a mix of Ukrainian parliamentarians, representatives of judicial institutions and the bar, and civil society activists – key stakeholders who together could foster the political will needed to create the HACC. They hoped that lessons learned in Slovakia could be applied in Ukraine, especially as regards what not to do. During the visit, they gained first-hand knowledge of the handling of corruption cases, from investigation and prosecution through adjudication by the SCC and, in some cases, appellate review by the Supreme Court.

Several important recommendations resulted from this visit. Slovakia’s experience made clear the need to link the court to the government’s overall anti-corruption strategy, define the jurisdiction of the court to focus on significant high-level corruption cases, ensure that the court has national jurisdiction in order to limit local interference and influence on corruption cases, avoid combining appellate and cassation review of corruption cases in one court, apply special screening requirements to the selection of judges, and provide judges with increased salary and greater security. The delegation also studied a constitutional challenge against the SCC, learning that would prove invaluable in responding to a similar claim later filed against the HACC.

Back in Ukraine, it took full-scale advocacy, cooperation, and strong messaging with ‘one voice, one mission’ to keep creation of HACC on the agenda. Civil society actors took a leading role, including the Anti-Corruption Action Center (AntAC), Centre of Policy and Legal Reform, DEJURE Foundation, Transparency International Ukraine, and the coalition group Reanimation Package of Reforms. They actively questioned the capacity of the judiciary to handle high-profile corruption cases and stressed that a dedicated anti-corruption court would bring efficiency, integrity, and expertise to the process. They advocated for the appointment of judges with impeccable reputations, selected through a transparent procedure, for the efficient consideration of these cases.

This was supported by regular coordination with international donors. In January 2017, the OSCE Project Coordinator prepared a concept for establishing the court, and this was followed by another one drafted by AntAC in March 2017. To combine efforts, international donors together with civil society agreed upon a common understanding for establishing the HACC. Key structural questions included how to avoid design features that would make the HACC a ‘special’ or ‘extraordinary’ court, which is barred by the Constitution of Ukraine, and how to organise the appellate chamber with the appropriate level of autonomy within the overall three-tier judicial system. Equally critical was the question of how to preserve the uniform status of judges, who would be selected for lifetime appointment by the president upon recommendation of the High Council of Justice. Judges had to be at least 30 years old and have a law degree with no less than five years of professional experience, as well as meet additional criteria to ensure integrity and specialised professional knowledge. The vision for the court outlined in the common understanding also included the first reference to a ‘selection panel’ to vet the integrity of judicial candidates; this panel would ultimately become the Public Council of International Experts.

MPs from the Samopomich Party registered the first draft law on the HACC (no. 6011) in March 2017. This was unanticipated by the expert and donor community and was seen as a political move to pressure the government to take action. The draft law proposed establishing a system of anti-corruption courts, including a High Anti-Corruption Court and an Anti-Corruption Chamber within the Criminal Cassation Court of the Supreme Court. It also included requirements for becoming a HACC judge and special vetting and selection procedures. Although the draft provided a framework for creating anti-corruption courts in Ukraine, it also raised constitutional questions as it provided for a different status, governance structure, and disciplinary processes for HACC judges. This concern was echoed in a critical Venice Commission opinion on this draft law issued on October 9, 2017, that helped advance discussions on establishing the HACC. The opinion reflected the importance of adapting European standards to the local context.

The Venice Commission made several recommendations to reduce the risk that the draft could be considered unconstitutional, and it invited then-President Petro Poroshenko to promptly submit his own draft law on anti-corruption courts based on the Venice Commission recommendations. The Venice Commission called for key components of draft no. 6011 to be maintained, namely, the establishment of an independent High Specialised Anti-Corruption Court, with appellate instance and with judges of impeccable reputation, transparently selected on a competitive basis and provided with adequate protection. The Venice Commission added that international organisations and donors active in providing support for anti-corruption programs in Ukraine should be given a temporary but ‘crucial role’ in the body empowered to select specialised anti-corruption judges, with due respect for the principle of Ukraine’s sovereignty. In December 2017, the presidential administration submitted to Parliament another bill, this one drafted by a group of previously unknown ‘experts’ wrongfully associated with the OSCE. Parliament subsequently changed the presidential draft to limit the court’s jurisdiction to cases investigated by NABU in order to better align with Venice Commission recommendations.

As Parliament was considering these two draft laws, the international community, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, European Union (EU), United States, and Canada, stepped up pressure to promote the court. They focused particular attention on the process for selecting HACC judges with impeccable integrity. They hoped to avoid repeating past mistakes, notably the failed process for selecting the chair of the NAPC, and to emulate good practices, such as the successful selection of the NABU head, which included a significant role for internationals on the selection panel. Local civil society organisations (CSOs) strongly supported a role for international experts. They pointed to the structural inability of the Public Integrity Council (an advisory body to the HQCJ) to block candidates with questionable integrity from being appointed to the Supreme Court, due to the Council’s weak vested powers. CSOs pushed for a fully international selection body, the Public Council of International Experts (PCIE), that would have veto power over HACC appointments. In the end, a compromise denied an absolute PCIE veto but mandated a joint meeting of the six PCIE members and 16 HQCJ members. If at least half of the PCIE members vote against a candidate, a plenary vote is triggered; this requires at least three PCIE votes and nine HQCJ votes, a total of 12 votes, for a candidate to proceed.

Financial incentives played a key role in advancing the adoption of the amended presidential draft into law. The IMF, working in close cooperation with the World Bank, linked future financial support for Ukraine to establishment of the HACC. The EU further included the HACC in talking points with the government and incorporated support for anti-corruption agencies into its action plan for Ukraine, linking them to visa liberalisation. The EU also referenced the HACC in its report under the Visa Suspension Mechanism on December 20, 2017, and the annual Association Implementation Reports. The Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA) programme and memorandum of understanding between the EU and Ukraine cited the HACC. The third MFA programme referenced asset declaration and the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA), and the fourth linked the first tranche of financial assistance to budget support for the HACC in 2019 and the launch of the PCIE selection of judges. The second tranche included the appointment of judges and providing financial resources to make the court operational.

These international conditionalities appear to have been necessary and responded to Ukrainian public demand for progress towards forming the court. Although establishing the HACC would have demonstrated political will to tackle corruption, the government seemed determined to drag out the process unnecessarily. President Poroshenko publicly resisted the court, frequently stating that ‘all courts should be anti-corruption courts’. It was reported at the Yalta European Strategy Forum in September 2017 that the President wrongly argued that anti-corruption courts exist only in ‘third-world countries like Kenya, Uganda, and Malaysia’ and questioned their effectiveness.

Nonetheless, with persistent pressure from a vocal civil society, the government was forced to proceed with critical legislative reforms and to provide resources for launching the court. At the same time, local experts received coordinated support from the international community to create a legal framework for the HACC. This process directly answered key institutional design questions as outlined in the U4 publication Specialised Anti-Corruption Courts: A Comparative Mapping. They included (a) the relationship of the specialised anti-corruption court to the regular judicial system; (b) the size of the court; (c) the procedures for appointing and removing judges; (d) the substantive scope of the court’s jurisdiction, and (e) its relationship to prosecutorial authorities. These questions were at the core of discussions and defined the scope of the law.

Lesson learned

Clearly answer design questions, prior to drafting laws, through broad stakeholder consultations to build consensus, together with an advocacy campaign. This approach can overcome reluctance and even direct resistance on the part of the government.

In the end, motivated by pending presidential elections and financial assistance from the IMF and EU, President Poroshenko reluctantly supported Parliament in adopting the Law on the High Anti-Corruption Court. The law was approved on June 7, 2018, just over two years since the HACC was first codified in law.

The law formally recognised the HACC as part of the judiciary, with nationwide jurisdiction. Its provisions and regulations incorporated a number of innovations into the legislative framework for the judicial branch. In particular, the law established a separate appellate chamber within the HACC. A unique model for Ukraine, this resulted in the court having both first and appellate instances within a single legal entity, but with separate administrative structures, staff, and premises. The law also required the HQCJ to establish the Public Council of International Experts, with administrative support provided by the State Judicial Administration, to support the vetting of judicial candidates. It defined additional requirements for HACC judicial candidates to allow for the widest participation of judges, lawyers, and academics in the competition. It set rules for selecting a subgroup of the HACC judges to serve as investigative judges, in charge of considering pretrial motions. The law also provided additional security guarantees for HACC judges and their families, and special security measures for HACC courthouses.

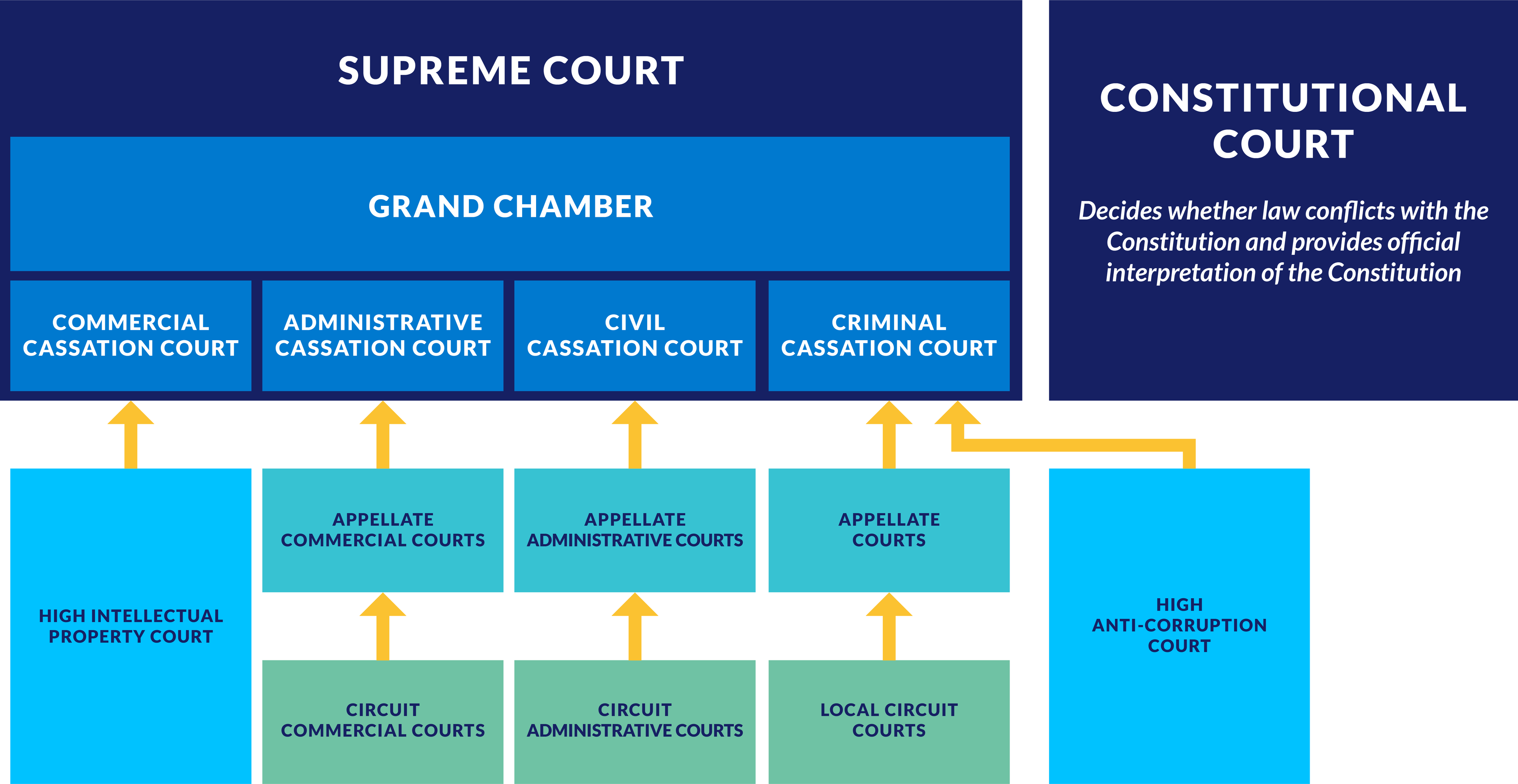

A critical gap in the legal framework concerned the cassation level, the highest level of review. The law provided that decisions by the HACC would be reviewed in cassation instance by Supreme Court justices, who were not subject to the same rigorous vetting process involving international experts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Ukrainian court system

Adapted with permission from USAID New Justice Program.

3. Selection of judges

The impact of the newly created PCIE on the judicial selection process cannot be overstated. In nominating experts to serve on the PCIE, international donors and local CSOs came together and submitted a unified list of 12 candidates to the HQCJ. The list reflected an ‘organic consensus’ that emerged after the stakeholders had shared candidate resumes and cross-checked proposed candidates. Once the PCIE members were appointed, however, another gap in the law became apparent. It was not clear who would be responsible for providing the PCIE with financial and administrative support, from paying fees and covering expenses to establishing a fully staffed secretariat. It took the issuance of a government decree to cover PCIE member expenses, including state funding for travel, lodging, and remuneration, while international donor support for the secretariat provided administrative and analytical assistance to PCIE members.

Even though the second round of selection of Supreme Court justices was simultaneously underway, forcing candidates to apply for one judgeship or the other, 343 candidates applied to be HACC judges, including 103 for the appellate chamber. Within a very tight, legally mandated 30-day time frame, the PCIE efficiently vetted the integrity and credentials of shortlisted HACC judicial candidates. Critically, CSOs formed a ‘brain trust’ that helped the mainly international, non-Ukrainian-speaking PCIE ramp up quickly in the local context and analyse vast amounts of data.

The PCIE members agreed on a common definition of integrity as well as a ‘reasonable doubt’ standard for assessing it. Access to electronic asset declarations (which are publicly available), public registers, and related data was key, even though many records and declarations were incomplete, and the 30-day deadline meant a risk of missing details. The candidates included sitting judges as well as practicing lawyers and law professors. Compared with judges, it was notably harder to conduct background checks on law professors and practicing lawyers due to the limited publicly available information about them. IDLO swiftly hired and trained analysts who tapped into a variety of resources to access information about candidates, including revealing social media posts. Also, CSOs like DEJURE, AntAC, and Transparency International Ukraine, supported by the EUACI, the USAID Support to Anti-Corruption Champion Institutions (SACCI) Program, and other donors, sent information about candidates to the PCIE secretariat. The PCIE also worked with media and journalists, using them as a source of information about candidates and as a mechanism for public outreach in explaining the selection process.

In cases where additional information or explanations were necessary, the PCIE also asked candidates to respond to specific questions. Armed with useful details about candidates gleaned from their responses, the PCIE was able to interview them more effectively. They linked questions to declarations and other sources of information and asked closed ‘yes or no’ questions during interviews, which were livestreamed for all to see. It could be a gruelling experience. One candidate who had no integrity issues, and who was ultimately appointed to the court, nonetheless remarked during stakeholder interviews that ‘life did not prepare me for the PCIE’.

After initial resistance, HQCJ members, particularly the non-judge chair, came to appreciate the PCIE for their professionalism and preparation. Although HQCJ members had been through a number of trainings on international and European standards for selecting highly qualified judges, it was not until they engaged in peer-to-peer exchanges with the PCIE, and witnessed first-hand the effective questioning of candidates, that they fully understand how to evaluate potential judges more effectively. It should be noted, though, that further HQCJ performance was not significantly influenced by this experience. Moreover, 28 sitting judges who were found to have questionable integrity and rejected as candidates after PCIE review are still on the bench in courts of all jurisdictions at local and appellate levels. The HCJ failed to initiate any disciplinary proceedings following a review of HQCJ records, with the formalistic explanation that the PCIE had assessed candidates for specific qualifications to be a HACC judge, not a judge in a general court.

The selection of HACC judges was finally completed on March 28, 2019, and 38 judges took the oath of office on April 11, 2019. They were a young and very diverse group, nearly 40% female and with a median age of 40. Half of those appointed had been practicing lawyers or law professors prior to joining the court. Of those who had previously served as judges, half were from regions outside Kyiv and had only considered lesser criminal or administrative cases. Despite their different backgrounds, their common attributes as identified by HACC judges themselves during interviews included readiness for change, fearlessness, independence, interest in professional development, and a strong desire to help the country develop.

Lesson learned

Create a protocol for transferring ongoing cases from existing courts to the new anti-corruption court to prevent overloading the court from the very beginning of operations.

Once the HACC judges were formally appointed to take the bench, they had nowhere to go, as a courthouse had not been prepared for them or staff hired. In response, the EUACI, IDLO, and USAID New Justice Program came together to support the development of a roadmap for making the court operational. The plan covered courthouse facilities, finance and budget, human resources, court security, IT and cybersecurity, and communications. It was intended to stimulate and guide action by government officials, including the State Judicial Administration, the national court administration agency that is responsible for ensuring proper working conditions for the HACC and the country’s other courts.

The election of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in April 2019 and parliamentary elections in July 2019 also played a central role in advancing the HACC. President Zelenskyy supported the allocation of temporary courthouse facilities. He also promoted the adoption of amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code by Parliament to ensure that the HACC would not be immediately burdened with nearly 3,500 cases transferred from ordinary courts nationwide. The amendments limited the transfer of cases to those investigated by NABU and prosecuted by SAPO, with other cases remaining in the courts where they had been originally filed. As a result, the HACC was able to formally launch its operations on September 5, 2019, without being overwhelmed with cases on the first day.

4. Preparing judges to take the bench

The HACC judicial selection process resulted in the appointment of judges with varied professional backgrounds and different levels of experience in criminal law. To perform their duties fairly and effectively, the new judges would need a deep understanding of the law and judicial practice related to corruption cases and protection of human rights. It was therefore essential that they receive detailed, in-depth, and wide-ranging training to hone their skills and knowledge. Such training would foster the independence and impartiality that would enable the HACC to be respected and trusted by the public.

Toward this end, the EUACI, EU Pravo-Justice Project, EU Advisory Mission to Ukraine, Canadian-Ukrainian Support to Judicial Reform Project, and USAID New Justice Program supported the National School of Judges of Ukraine (NSJ) in designing, implementing, and evaluating an orientation program for the new HACC judges. In designing the program, as part of the ‘turbo regime’ to prepare the judges for the bench, the NSJ conducted a needs assessment in which the newly appointed judges completed an online survey to identify priority topics. These included aspects of substantive and procedural law, such as defendant’s rights in criminal proceedings, illicit enrichment, asset forfeiture and recovery, multinational corruption crimes, and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights related to corruption cases. Equally important were judicial ethics, including how to apply conflict of interest rules in practice and how to seek advisory opinions from the Council of Judges of Ukraine to avoid potential misconduct. Other topics to be covered included opinion writing in criminal matters; caseflow management and working in panels; the psychological aspects of being a judge, given the interplay between emotion and decision making; and the interaction with other anti-corruption institutions, especially NABU, SAPO, and ARMA. This feedback was critical to designing a program that met the needs of the judges.

One challenge from the start was incorporating those who had not previously served as judges. Together with the NSJ, USAID New Justice Program supported an initiation, prior to the full three-week orientation program, for judges who had been lawyers and law professors. This focused on aspects of transitioning to the judicial profession, such as the role of a judge in a democratic society and the disciplinary liability of judges. To help them prepare for the bench, these judges were provided with copies of the Code of Judicial Ethics along with resource materials prepared by USAID New Justice Program. These included To Be a Judge: An Introduction to the Profession, a Ukrainian-language volume based on The Judge’s Book, published by the National Judicial College in Reno, Nevada. Other materials, also in Ukrainian, included Handbook on Writing Court Decisions, Disciplinary Proceedings against Judges, and Personnel Policies in Courts: Modern Experience.

The subsequent full orientation program covered all the topics identified during the assessment phase while adding specific aspects concerning the basic principles for managing complex criminal cases; protecting witnesses, experts, and victims; evaluating competing pieces of evidence and processing cases with complex electronic evidence; and imposing sanctions for lawyer misconduct in court. It also included face-to-face experience-sharing sessions with distinguished anti-corruption court judges and experts from Serbia and Slovakia, who provided both encouragement and caution about achieving quick results. The program was particularly important for those sitting judges and non-judges without a criminal law background, as nearly half had no previous experience in handling corruption cases.

In terms of ongoing training needs as assessed by the NSJ following the orientation program, judges suggested additional programs on the application of European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence, understanding the intricacies of financial instruments, and accessing information through mutual legal assistance channels. They also highlighted stress resistance and emotional intelligence, given the high level of public expectations and the demands of managing high-profile defendants with aggressive lawyers. Since they sit in panels of three, judges noted that working in teams remains an important subject. In terms of practical judicial skills, they emphasised that more training on how to respond to ethical dilemmas in practice and in courtroom management would be helpful. This is an area where experienced judges have been helpful to their colleagues in peer-to-peer exchanges and mentoring.

As ongoing professional development is a prerequisite to being an effective judge, and HACC judges have a considerable workload, they requested that training sessions be conducted in the evenings and on Saturdays. They also asked that trainings be planned at least three months in advance to ensure their participation. In this regard, easily accessible online programs and webinars have proven beneficial, particularly because of COVID-19 restrictions. Throughout the pandemic, HACC judges have engaged in distance education programming, ranging from the art of sentencing to mindfulness, at flexible times most compatible with their schedules. Overall, continuing judicial education for HACC judges is a career-long process that endures far beyond appointment.

5. Developing administrative and organisational structures

Judicial administration enables courts to fairly, expeditiously, and economically handle disputes brought to them for resolution. It serves to guide the court’s structure and case processing in line with the rule of law, equal protection, and due process. Successful courts are well administered and managed, which makes them more independent and trusted. The primary objective in developing administrative and organisational systems for an anti-corruption court is to lay the foundations for efficient, transparent, and effective operations. As outlined in the core competencies for court managers developed by the US National Association for Court Management, proper court administration involves sound operations management of courthouse facilities, court security, IT infrastructure, and public relations through court communications. These topics are addressed in detail below.

Lesson learned

Begin planning at least one year in advance of operations to ensure that administrative systems, court staff, and court facilities will be ready for operations when judges are appointed.

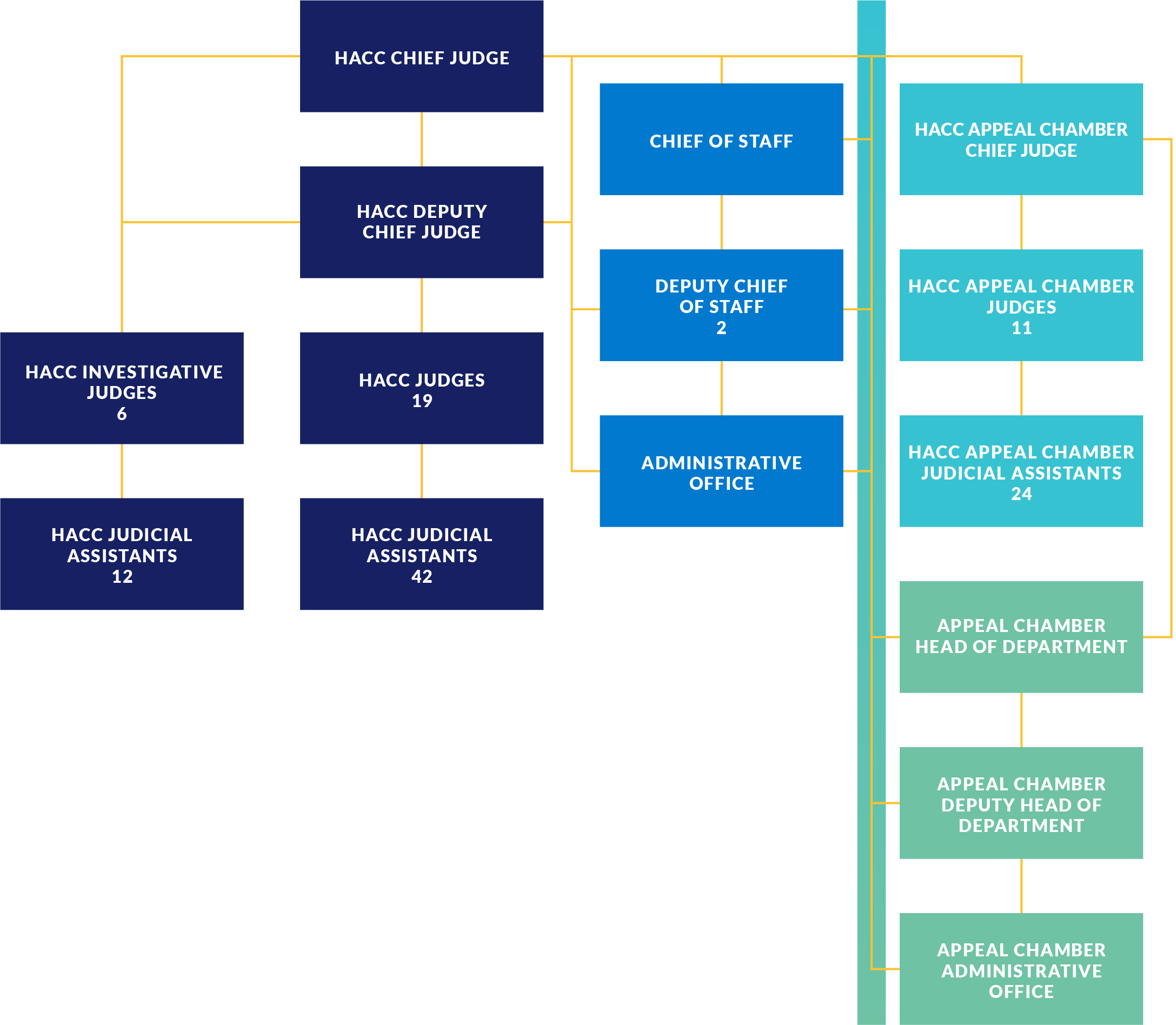

One of the first steps in setting up the administration of the HACC was the election by the court’s judges of a chief judge and deputy chief judge, as well as an appellate chamber chief judge (see Figure 2). The role of the chief judge and deputy chief judge as court leaders and ‘first among equals’ is critical. Key qualities that were identified by HACC judges in electing their leadership included the ability to communicate and listen well, in-depth knowledge of criminal law, and an understanding of how to manage anti-corruption cases. These qualities enable the chief and deputy chief to provide fellow judges with substantive guidance. It also goes without saying that the leadership must have unimpeachable integrity. This was recently highlighted by the removal of the head of the Specialised Criminal Court in Slovakia. He is now being prosecuted for serious violation of his duties, as he did not recuse himself and lied about his contacts with a lawyer in a high-profile case.

To help the newly elected chief judges assume their leadership positions with integrity, USAID New Justice Program provided one-on-one coaching sessions with prominent international judicial administration experts on the foundations of being a leader and leadership in action. The first part of this three-day program focused on how to develop a leader’s philosophy, identity, communication, behaviour, thinking, and demeanour. The second part addressed the day-to-day work of the chiefs and their relationships with the court administrator, the deputy chief judge, and the other judges on the court. The training stressed skills in governance, policy development, and systems planning and management.

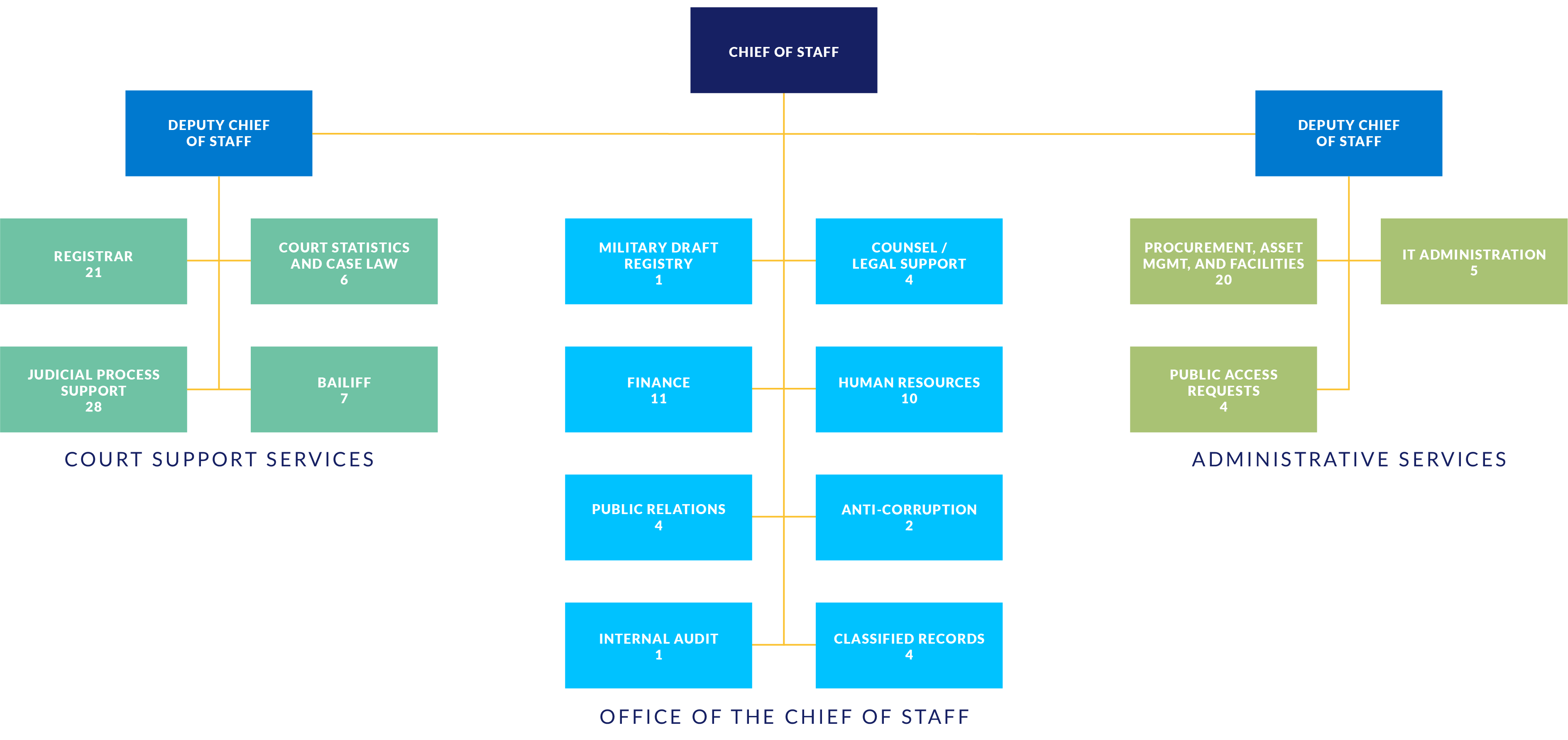

In creating administrative systems, the HACC leadership established departments, internal regulations, tender committees, and a staff selection commission (see Figure 3). They also set up working groups on the unification of court practice and case management. This included addressing issues related to the automated assignment of cases to panels of three judges, at least one of whom should have at least five years of judicial experience. This requirement for the automated random assignment of cases was introduced with USAID New Justice Program support before the establishment of the HACC to ensure transparency and integrity in assigning cases. It is of particular significance when dealing with high-profile corruption cases; previously, non-automated case assignment provided opportunities to manipulate the process for corrupt purposes, which is now a crime. Nevertheless, this requirement causes difficulties for the operations of the HACC in forming panels. Some judges and experts propose amending legislation to provide for the consideration of first-instance HACC cases by a single judge while requiring a three-judge panel for only the most complex cases. Opponents of this idea stress the benefits of collegial decision making and knowledge sharing and the low risk of possible undue interference.

Figure 2. HACC organisational chart

Adapted with permission from USAID New Justice Program. Numbers refer to the number of personnel associated with the unit or function.

Figure 3. HACC administration organisational chart

Adapted with permission from USAID New Justice Program. Numbers refer to the number of personnel associated with the unit or function.

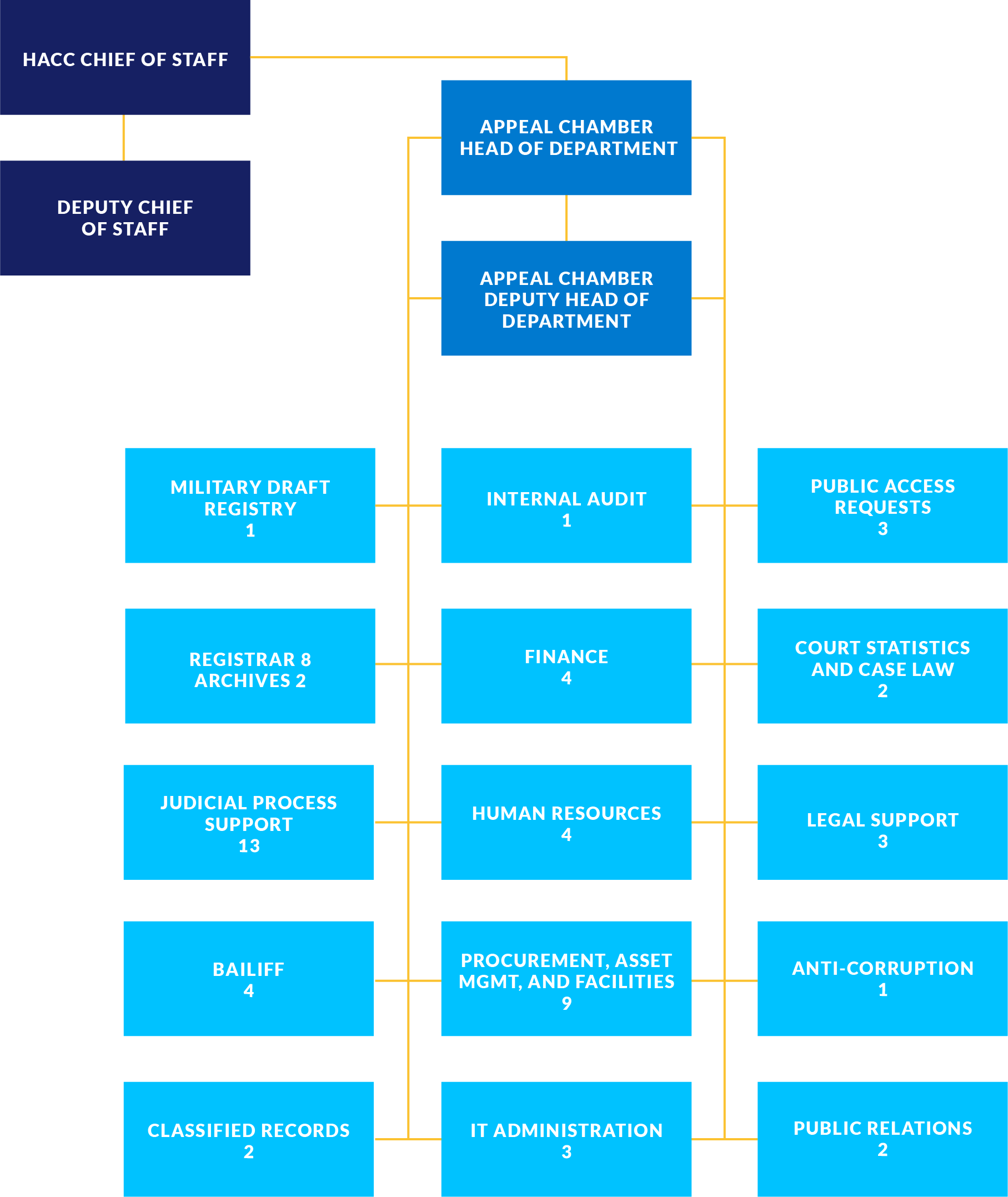

As the HACC is a single legal entity by law, the chief judge of the court, a first instance judge, is administratively the head of the appellate chamber, which has its own chief judge (see Figure 4). This complicated structure has led to procurement issues, such as the inability of the appellate chamber to process its own administrative needs independently due to legal limitations. Although the Council of Judges, as requested by HACC chief judges, issued an opinion concluding that there is no conflict of interest in a lower court chief judge overseeing appellate court judges, many noted that this demonstrated the need to legally separate the appellate chamber to eliminate any possible ethical concerns as well as ease administrative burdens and improve overall budgeting.

Figure 4. HACC appellate chamber administration organisational chart

Adapted with permission from USAID New Justice Program. Numbers refer to the number of personnel associated with the unit or function.

5.1. Courthouse facilities

Adequate courthouse facilities are critical for the effective administration of justice. This includes courtrooms, judicial chambers, and office space for court staff, arranged so as to allow separate circulation patterns for the public, defendants (particularly those in detention), and court personnel.

As noted above, when HACC judges were sworn in, no courthouse was readily available for them to begin hearing cases. The State Judicial Administration (SJA) said at the time that there were limited facilities available in Kyiv. Nevertheless, the SJA proposed interim facilities while permanent courthouses were being considered. The interim courthouses that were located for the investigative, first instance, and appellate judges included three buildings far apart from each other with an inadequate number of courtrooms. Although two of the facilities were former courts, the main courthouse was a former bank that was identified by the court leadership itself.

In support of making the court operational as soon as possible, USAID New Justice Program assisted the SJA in preparing an infrastructure plan as a roadmap for completing renovations at the three interim courthouses. Based on a needs assessment, the roadmap called for a fast-track process that would meet only the minimum requirements to ensure the safety of the public, judges, court staff, and defendants. Special requirements for the HACC also included a secure space to handle top-secret materials related to national security.

The HACC chief judge and chief of staff took the initiative regarding facilities, but found that they had to waste time and energy on courthouse concerns. Questions related to permanent courthouses remained unanswered by the government, even though the most recent IMF conditionality required that the HACC be provided ownership of permanent, appropriate, and secure facilities for the trial and appellate chambers by the end of August 2020. Only on April 21, 2021, did the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine officially transfer ownership of the main courthouse to the High Anti-Corruption Court. Two other buildings, including one housing the appellate chamber, are still leased by the HACC. HACC judges and staff would prefer to be in a single, permanent courthouse for better security and enhanced communication with one another.

5.2. Court security

Given the nature of administering justice in high-profile corruption cases, security is essential. As highlighted in the National Center for State Courts Court Security Resource Guide and the Conference of Chief Justices Court Security Handbook, steps must be taken to ensure that every judge, judicial employee, defendant, and court visitor is protected from threats of any kind.

Article 10 of the Law on the High Anti-Corruption Court provides for the personal security of judges, including bodyguards and an alarm system at their private residences if requested. Unfortunately, efforts to make the HACC operational coincided with the creation of a completely new Court Security Service (CSS) under the State Judicial Administration. This new service should have started in 2015, pursuant to legal amendments adopted at the time, but launched its operations only in 2019.

Lesson learned

Establish a separate security service or department directly within the judiciary, especially given the special nature of anti-corruption courts and the importance of the judiciary as a separate and independent branch of government.

The CSS began with very limited funding and was initially not able to hire enough qualified court security staff. In response to the unique needs of the HACC, the CSS established a special department dedicated to the court. This unit conducted a threat analysis and court facility site survey, covering all three temporary buildings. It noted that the former bank was particularly difficult to refit for security purposes with different areas and dedicated flows for judicial personnel and non-judicial court visitors.

The CSS later assigned its most experienced officers to the HACC, who reportedly came to know every inch of its three facilities ‘better than their own apartments’. As part of its risk-based approach to security management, the CSS works closely with the police to assess and monitor risks to the HACC, including monitoring of social media and other open sources, to minimise any potential threat. This included supporting the court in preparing an emergency management plan. The CSS provided security training for judges and staff, building on a session at the judicial orientation program conducted in April 2020. Judges have emergency buttons in their chambers and courtrooms and can request additional security assistance at any time.

Although there have been only a few reported threats to the HACC, including a minor explosion near the main courthouse, some judges fear for their safety on and off the bench. Two have requested 24/7 security. A gap in the law is its inattention to the security needs of judicial assistants (law clerks), which is of concern given their role is supporting judges with legal research and opinion writing. This is currently being addressed by the EUACI and USAID New Justice Program in discussions with the Parliament’s Legal Policy Committee.

5.3. IT infrastructure

Court automation efforts can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of court operations and promote transparency in judicial proceedings, as underlined in USAID’s Designing and Implementing Court Automation Projects. This is of even greater significance for anti-corruption courts, which need to model clear, transparent, and clean processes. A complete court IT infrastructure requires hardware, software, and installation, as well as training and support for users.

Lesson learned

Develop IT infrastructure based on user needs to promote efficient, effective, and transparent court operations.

Several donor projects, including the EUACI and USAID New Justice Program, contributed to the establishment of the HACC IT infrastructure through the purchase of hardware and basic office software packages to ensure the timely launch of the court. As part of the general court system, the HACC is required by law to use the automated case management system that was developed and maintained by Information Court Systems, a state-owned enterprise under the State Judicial Administration. Drawbacks of this system include weak information security and limited functionality. Despite this legal mandate, several courts run different case management systems, including the Supreme Court and the Kyiv Court of Appeals. This fragmentation results from the lack of a unified IT governance policy and constrains integration and migration of case information across the judiciary.

Despite its limitations, the most widely used system for basic case management was installed in the HACC. The SJA is in the process of upgrading the system, but results are not expected anytime soon. The system has provided the basic infrastructure to support the court’s operations, including the automated random assignment of cases as well as standard email and accounting functions. However, it does not allow for real-time case tracking, which would support more effective case management and help personnel avoid missing critical deadlines. Assessments conducted by the EUACI and USAID New Justice Program recommended that the HACC be able to add alternative products to bridge this gap. In that regard, the EUACI is supporting an initiative that would allow NABU and SAPO to electronically share case information with the HACC, which would relieve judges from relying solely on volumes of paper files. On March 15, 2021, the president submitted to Parliament a draft law that would enable the electronic exchange of information between parties and courts in criminal cases. This draft currently awaits consideration by Parliament.

5.4. Court communications

Public trust in the courts cannot be secured by institutional mechanisms alone. Public outreach and education, including through the media, are central to successful court operations. The public can learn more about the courts, and the courts can bolster confidence through proactive engagement with the public and media. This includes engaging civil society organisations that can become advocates for the courts.

The HACC chief judges, elected at an early stage of the court’s formation, initially played a prominent role in speaking for the court. The court later developed a communications strategy to publicise the court’s mission statement and core values and counteract misinformation. Toward that end, the EUACI and USAID New Justice Program supported strategic planning and communications sessions with judges and court staff.

Box 2. HACC mission

Administer justice based on the rule of law in criminal proceedings regarding corruption cases and related crimes and ensure that everyone has the right to fair trial with respect for human rights and freedoms.

After hiring a communications director, the HACC set out to implement its strategy. An early step was to establish a social media presence through a Facebook page, YouTube channel, and website. The appellate chamber also has its own Facebook page and YouTube channel. Use of social media enabled the court to communicate directly with the public while responding promptly to frequent media requests. The court’s website was one of the first judicial sites to provide the public with information about the court’s COVID-19 response. The court also livestreamed an increased number of trials to open them to public view virtually. Information about court hearings and updates on pending cases are posted on a regular basis. The posts include case reference numbers that allow the public to access the court’s decisions on the Unified State Register of Court Decisions.

Box 3. HACC values

- Human rights and rule of law

- Right to fair trial

- Judicial independence

- Right to appeal a court judgment

- Transparency and openness of court proceedings

HACC communications are strengthened by the role of judge-speakers, who participate in the court’s outreach activities in addition to their judicial duties. They may communicate with the media about highly publicised cases or discuss the court’s activities that are of interest to the legal community or general public. Judges also give lectures at high schools and universities, and the court hosts student visits. The judges’ role in communicating with the public, the government, and international partners is particularly important during challenging situations. The court has drafted a dedicated communications plan for high-profile cases that reflects different situations that could arise in dealing with well-known defendants.

Clear messaging in simple language enables the court’s message to be heard and understood by varied audiences. It can also help the court manage expectations, especially by explaining procedural limitations and defendants’ rights. In support of this effort, USAID New Justice Program conducted communications trainings to develop public speaking skills for judges and communications staff, along with a data visualisation program to strengthen communications products. The court was also provided with key publications, such as a Ukrainian edition of Public Relations in Courts. The court considers that one of its goals is to contribute to increasing legal literacy throughout the country. In this respect, USAID New Justice Program assisted the court with developing and printing an informational leaflet and poster about the court for display in courtrooms, judicial chambers, and administrative offices.

Measuring the impact of court communications activities is challenging. The court tracks the number of views of its website, approximately 70,000 per month in early 2021, as well as Facebook indicators, such as the number of subscribers to the main court page (8,000+) and appellate chamber page (2,000+), along with shares, likes, and comments. The YouTube channel for the court has 2,000+ subscribers and 500+ videos uploaded. The HACC also conducts daily and weekly media monitoring and analyses feedback from journalists and lawyers to measure both the quality and quantity of its public outreach initiatives. This includes monitoring how often reporters themselves have accessed the court’s social media posts and whether they actually use the information from these posts in news stories or broadcasts.

Over the past year, the court and its judges have faced a number of targeted attacks in the media, with negative information broadcast on news programs and posted online. This has tested the communication department’s ability to respond effectively. The latest example includes a media report on the participation of the court’s chief judge at an event that included judges from other courts who are under criminal investigation, and whose cases may ultimately come before the HACC. Overall, however, the court successfully manages relations with the media regarding high-profile trials, including publishing announcements before hearings and detailed press releases once a decision is rendered. Chief judges, judge-speakers, the chief of staff, and the director of communications all work together to engage national and international media as well as professional legal publications by giving interviews and writing articles.

In addition to external communications, the court has internal communications policies and procedures. These are intended to develop the court as an institution and address challenges, including its location in three different premises. The court also constantly works to develop the communications skills not only of the communications team and judge-speakers but also of ordinary judges and court personnel. The communications team pays special attention to cultivating a culture of transparency to ensure access to information for everyone working at the court. As a result of internal communications efforts together with external initiatives, the HACC has earned a higher level of support from the judicial community. According to a 2021 USAID New Justice survey, 48% of Ukrainian judges believe that the High Anti-Corruption Court has a positive impact on combating corruption in Ukraine, which is up from 31% in 2019 when the court started operations.

6. Recruiting, hiring, and onboarding court personnel

The unique caseload of the HACC presents specific challenges related to staff that other courts do not routinely face. Responding to these challenges requires a different approach to staffing, along with investment in additional professional capacity building. Staff must have the necessary skills to provide security for whistle-blowers, informants, witnesses, and victims; oversee electronic/digital evidence management and control; use technology to present audiovisual and electronic evidence in court hearings; and conduct court media, information, and public outreach services.

Building on the standard court staffing plan, job descriptions developed by the State Judicial Administration, and recommendations to enhance competencies, the HACC quickly began recruiting candidates for the 281 planned staff positions in both the first instance court (197) and appellate chamber (84). An overriding objection was the selection of court staff with integrity. This was complicated by the fact that some court staff are civil servants, whose positions must be advertised and filled competitively, while others are direct hires, such as judicial assistants who are hired by judges themselves. The judicial assistants are not subject to anti-corruption monitoring obligations and do not have to submit asset declarations, as is required of staff who are civil servants.

A major challenge for the HACC was that critical court staff had not been selected before the judges were appointed to allow for immediate operations. This, however, made it possible to hire court staff through the same rigorous process used to select the judges, with background and integrity checks. Such checks proved to be more difficult for candidates who were not previously civil servants, as available information (such as asset declarations) was limited. As a solution, selection commissions conducted thorough interviews, checked candidates’ social media posts, and sought out references from previous employers with tailored questions. If the candidate had worked in a court, it was useful to contact courts where they had worked and judges that they worked for to ask about integrity concerns. Some staff, however, were transferred from other courts directly to the HACC without further background checks.

International partners were also directly involved in selecting key court staff, including the chief of staff, IT specialist, archivist, and communications director. This included developing evaluation metrics and questions geared towards specific positions, as well as crafting hypothetical ‘moral dilemmas’ to which candidates were asked to respond. International experts were also allowed to ask questions of candidates during interviews, making the process more open and more competitive than staff selection for any other court. With respect to candidates’ backgrounds, previous public administration experience proved more important than private sector management skills.

Lesson learned

Conduct rigorous background checks in hiring court staff to ensure integrity.

Once the staff was hired, onboarding and orientation programming proved to be essential. For the chief of staff, USAID New Justice Program designed and implemented coaching sessions with international judicial administration experts on caseflow management, court budgeting and fiscal management, cybersecurity, and security of court buildings and personnel. The chief of staff also received training on how to handle co-leadership with the chief judge. The court’s communications director received a specialised orientation on modern approaches to court communications. All staff were engaged in developing the court’s mission and values together with judges. They also received the Rules of Conduct for Court Employees, adopted by the Council of Judges for all judicial personnel to help guide them in responding to ethical dilemmas.

In terms of remuneration, which is very low throughout the judiciary and results in high turnover, interviewed partners suggested that policymakers should consider paying HACC court staff more, given the specialised nature of the court. A comprehensive system of staff performance evaluation was recommended as well. Also, the future selection of judicial assistants should be standardised by fully advertising positions, requesting writing samples, and using a consistent set of interview questions based on evaluative criteria, focusing on issues such as motivation and integrity. Judicial assistants should also receive specialised training programs that cover judicial opinion writing, ethics and integrity based on the Rules of Conduct for Court Employees, and time management.

7. Evaluating court performance

The goal of any court is to provide quality justice within a reasonable time, which is a key indicator of successful administration of justice. Assessing a court’s performance is critical to building trust and confidence and requires a holistic approach covering a broad range of factors related to access, efficiency, fairness, and user satisfaction. As emphasised in the International Framework for Court Excellence, this includes creating a court culture that promotes reform, service improvement, and innovation. Moreover, effective courts operate according to standards based on public expectations for court performance. These encompass criteria, indicators, and methods included in the Court Performance Evaluation Framework developed with USAID New Justice Program assistance and approved by the Council of Judges of Ukraine for the internal and external evaluation of Ukrainian courts.

As a central institution in the anti-corruption infrastructure and a key structural pillar of anti-corruption reform, the HACC faces public demands that are much higher than those for any other first instance or appellate court. In general, the public expects timely, efficient, and fair adjudication of high-profile corruption cases. In the Ukraine Request for Stand-By Arrangement adopted in June 2020, the IMF further requires the HACC to publish performance reports detailing the number and types of corruption cases, decisions on convictions or acquittals, and imposed sanctions. With respect to these and other measures, during its first 16 months of operations the HACC has made significant progress, which is reflected in civil society monitoring conducted by Transparency International Ukraine.

The HACC’s own statistical reports and related conviction data show that the court is doing relatively well in comparison with courts that previously handled similar cases. In the four years prior to the launch of the HACC, 2015 to 2019, courts nationwide issued about 33 convictions in NABU-investigated cases, 90% of which were plea agreements (precise statistics are not available, as cases were dispersed throughout Ukraine). By February 2021, in its first 16 months of operations, the HACC issued 15,253 decisions, including 15,229 pretrial rulings, one acquittal, and 23 criminal convictions, two of which were reversed by the HACC appellate chamber. Despite this excessive workload, the HACC was able to keep up with incoming cases, while holding the backlog under control with clearance rate of 101% in 2020 and 99% in the first five months of 2021.

Following an analysis of a number of HACC decisions, AntAC reported that they provided for the largest amounts of bail and the most custodial sentences for high-level public officials in the Ukrainian court system. Prosud also reported that the HACC recovered 65 million hryvnias (approximately US $2.4 million) in assets and returned them to the state.

Also notable is the productivity of HACC judges. There are currently are 28 cases per panel on average, which has helped reduce the length of preliminary hearings to one-third the average for other courts. During the court’s first six months, HACC judges completed the review of 97% of applications, 95% of petitions, 81% of complaints, and 27% of all criminal cases that came before them. Before the establishment of the HACC, court decisions had been delivered in only 20% of all criminal cases submitted to the courts by SAPO, typically following months or years of consideration; the result was a significant backlog. The better performance of the HACC in comparison to other courts may have also contributed to the slightly higher level of public trust in the court compared to the judiciary as a whole, as noted above.

The HACC similarly performs better than other courts in terms of integrity. Out of 38 HACC judges, only two had integrity issues raised by civil society during the selection process; these judges later clarified the issues and went on to assume judicial responsibilities. In comparison, civil society found that 44 Supreme Court justices out of 192 appointed to the bench had outstanding integrity issues – and still serve on the highest court in the country.

HACC judges likewise have had very few judicial disciplinary actions taken against them.

Although judges enjoy functional immunity for conduct on the bench, the High Council of Justice has the authority to discipline them for misconduct and to impose sanctions that range from reprimand to removal from office, depending upon the gravity of the violation. Grounds can include failure to submit asset declarations or acknowledge a conflict of interest. HCJ judicial inspectors screen and investigate complaints of misconduct for adjudication by HCJ members. As of February 2021, the High Council of Justice had received 152 complaints regarding HACC judges. It opened investigations in just nine cases, deciding in two of these matters against investigative judges for procedural rulings. Another 41 complaints are still being assessed. Overall, the majority of complaints filed at the HCJ against HACC judges appear to be motivated by a desire, on the part of defence lawyers and the HCJ itself, to pressure judges by opening disciplinary proceedings against them.

With respect to gender breakdown, there are 14 women (40%) and 24 men (60%) among the HACC judges in both the trial and appellate chambers. Thus the HACC is male-dominated, unlike first instance and appellate courts nationwide, where 53% of judges are women and 47% are men. However, in terms of women in leadership positions, the HACC is ahead of the vast majority of courts, as reported by the SJA. Both HACC chief judges are women, while there are 37% women and 63% men among chief judges in first instance and appellate courts throughout Ukraine. Among HACC court staff, 62% are female, according to statistics provided by the court. This is in line with the general trend, as most administrative positions in courts nationwide are occupied by women, but it is significantly less than the national average of 80% female court staff.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the HACC continued its operations without delays, becoming one of the first courts to ensure a safe environment for judges, court staff, litigants, and visitors. Its efforts built on best practices presented in the National Center for State Courts publication Preparing for a Pandemic: An Emergency Response Benchbook and Operational Guidebook for State Court Judges and Administrators. While under strict quarantine limitations, 60% of the staff teleworked, allowing for proper social distancing in courthouses. Also, as noted earlier, HACC significantly increased the number of hearings broadcast online, allowing for greater public access to trials.

Despite these advances, some observers have expressed frustration and asked why the court is not moving faster. This reflects a general failure to understand that high-level corruption cases are complex and take time. The HACC is also trying to avoid the appearance of abusing the rights of defendants and due process guarantees. Here, once again it is important to manage public expectations.

A related challenge facing the court is meeting statute of limitations deadlines. These often leave little time for case consideration and may result in closing cases against defendants prematurely, further fuelling the perception of impunity. One solution is to manage cases better through a differentiated case management system. This could be accomplished through a simple Excel-based dashboard to allow the court and individual judges to track cases based on their complexity. This can be a standalone function or integrated into an automated case management system feature. It should include prioritising cases with defendants in detention.

Lesson learned

Conduct caseload analysis to accurately establish the required number of judges.

At the same time, HACC investigative judges are setting the standard with higher-quality judicial control over investigations and generally well-reasoned decisions related to search warrants, detention orders, and seizure of property overseas. Initially, the judges elected six of their number to serve as investigative judges. Later, as a result of increased caseloads, the group of investigative judges was enlarged with the election of an additional six. The court is also considering rotating investigative judges to balance experiences and workloads. It is now apparent that caseload should have been estimated at the start of the design phase of the court to ensure an adequate number of judges. The Law on the High Anti-Corruption Court prescribes the maximum number of judges for the court as 39, including 12 for the appellate chamber; however, the State Judicial Administration set these numbers arbitrarily, without conducting a detailed survey of the potential caseload. Caseload analysis should be an ongoing process, with regular reviews, to ensure a sufficient number of judges to consider cases.

Box 4. Sample performance indicators for an anti-corruption court

- Clearance rate

- Backlog (number of cases pending for more than one year)

- Duration of trial – time to disposition

- Conviction rate

- Reversal rate

- Quality of court decisions

- Number of investigative orders

- Number of hearings

- Number of cases reviewed by the European Court of Human Rights

- Money returned to government – confiscated property

- Number of communications products and tools, including press releases, organized campaigns, and news reports, as well as social media analytics

Additional monitoring indicators could include:

- Number of disciplinary complaints filed against judges

- Number of disciplinary decisions against judges

- Number of claims regarding interference in judicial decision making

Through their own high performance, the HACC judges, especially investigative judges, have increased pressure on NABU and SAPO to raise their game. Their investigators and prosecutors are reportedly performing better than others in preparing for trial and presenting evidence. Nevertheless, an important concern is that SAPO traditionally submits too much information. A common practice is to collect and submit as much evidence as possible even if some of it is irrelevant. This outdated approach has resulted in notices of suspicion of up to 50 pages and indictments with evidence placed in a ‘basket’, without reasoning or division into relevant issues. It is also not uncommon to have case files with 50 volumes, where nearly half the material is not pertinent to the case. There should be a greater focus on presenting exhibits and witness testimony, not piles of poorly structured evidence. This is particularly vital for complicated financial transactions, where expert testimony is key. Prosecutors and investigators need to become experts to simplify the work, narrow the scope for experts, and better persuade the court. Prosecutors as well as defence attorneys should be able to present proposed findings of fact and law in a way that is persuasive. Investigators, in particular, also need to work with analysts with financial backgrounds.

The court has had to deal with unsubstantiated submissions by defence lawyers with varying levels of professionalism, resulting in judges wasting time on frivolous claims, as reported in stakeholder interviews and the media. Defence lawyers are also looking for procedural wins, failing to cite substantive criminal code provisions. In some cases lawyers have used baseless excuses for not showing up in court, further delaying case consideration. Many HACC judges noted that not all areas are regulated in the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) and that they are developing practice. Creating basic rules of evidence with strict enforcement of a hearsay rule will reduce case files. Rules should also provide guidance on the admissibility and authenticity of the evidence, particularly digital evidence.

Lesson learned

Engage investigators, prosecutors, and judges in a dialogue to discuss common problems and identify solutions.

Another way to address these challenges is to conduct coordination meetings with SAPO prosecutors, NABU investigators, and defence attorneys to discuss procedural issues that would help them understand what to expect from the court. In one such meeting recently facilitated by an international criminal law expert, topics discussed included plea agreements, sloppiness in written materials, petty discovery issues, the possibility of judges finding counsel in contempt of court for misbehaviour, authentication of documentary evidence, and various pretrial investigation issues raised by NABU investigators. Some of these concerns require legislative solutions, while others can be resolved through a mutual understanding of CPC provisions and/or better training on courtroom presentations by SAPO.

Other performance enhancements include having a judge on call over weekends, calendaring with consequences for failure to appear, improving the overall planning of trials. Given the mix of professionals on the court, a good practice from the beginning has been to include at least one previously sitting judge on each panel of three judges in the first and appellate chambers. As a result, court observers have not noticed differences between former judges, lawyers, and law professors in terms of their judicial performance on the HACC.

The HACC is currently hearing several cases with prominent officials, including a former MP accused of embezzling $120 million in a gas scheme and the former head of the State Fiscal Service charged with embezzling $80 million. HACC is also hearing a complex embezzlement case related to a National Bank of Ukraine stabilisation loan in the amount of $50 million. Facing high caseloads, the court has demonstrated efficiency in moving forward cases that have lingered in other courts for years. At the same time, it has quickly adjudicated low-level, straightforward cases, such as those concerning the failure of government officials to file asset declarations. A recent case filed at the court resulted in the resignation of the current head of the State Judicial Administration, who has been charged with organised crime and bribery in a major corruption case against some of Ukraine’s most notorious judges at the Kyiv Circuit Administrative Court.

In the end, how the HACC continues to handle these and other high-profile cases will indicate its level of independence. It will also determine how much respect it receives from the public, which is awaiting the just and fair conviction of a prominent official as a sign of progress in combating corruption. The few low-level convictions secured thus far are not enough to relieve public pressure on the court, given the very political nature of the HACC. Nevertheless, the systems currently in place are sustainable and provide a template for the future. The framework created makes it possible to recruit judges and administrative personnel with integrity and to conduct efficient and effective court operations, despite recent financial limitations facing the entire judiciary.

8. Conclusion

Establishment of a fully functional High Anti-Corruption Court advanced the fight against corruption in Ukraine. However, there are a number of serious threats facing the court. Most notable is a recent decision of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine (CCU) that essentially dismantled the anti-corruption infrastructure by limiting the authority of the NAPC and overturned some of the court’s relatively minor convictions related to asset declarations. There is also a pending filing at the CCU challenging the constitutionality of the HACC itself. This has contributed to a decrease in the level of trust in anti-corruption institutions with trust in NABU declining from 19% in 2019 to 14% in 2021 and NAPC from 15% to 11%. The level of trust in the HACC after its first 18 months is also low at 10% which is the same level of trust in the overall judiciary. This can be linked to a concerted effort by vested interests to discredit and dismantle the anti-corruption infrastructure. These developments signal real hazards ahead for the court. Meanwhile, the lack of adequate permanent facilities hinders the day-to-day operations of both chambers over the long term.