Blog

What the Financial Secrecy Index tells us about corruption today

Corruption happens in two main stages. The first is the actual act of receiving something of value: a monetary bribe passed under a table, a public procurement contract awarded to a classmate from high school, a law quietly rewritten to benefit a particular firm.

However, corruption doesn’t end at the site of the crime – it extends to the places where the proceeds can be hidden, laundered, or protected from scrutiny. The second important stage is thus the legalisation and investment of the proceeds.

In many of the cases, this second stage is enabled and facilitated by what we call regulatory arbitrage opportunities: legislative differences between countries that make it valuable for companies and individuals to avoid the regulations of their home country. Yet, much of today’s corruption analysis still focuses only on the country where the bribe was paid or the contract manipulated, ignoring the context and the wider system. That’s like studying bank robbery by only looking at the robbed bank, and ignoring the getaway car or the robber’s house.

This is where the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) comes in. The index shifts our attention to the other end of the equation: the jurisdictions whose financial systems quietly enable corruption to flourish.

Grand corruption thrives in the offshore world

Financial secrecy does not cause the crime, but it determines how easy it is to hide it from authorities, escape accountability, and profit from it. If you can move your assets into an anonymous company, park them in a discretionary trust, or hide behind nominee directors – and do so in a country that won’t share information or cooperate with investigators from your home country – then the risk of being caught drops dramatically. Opportunity makes the thief.

That’s why secrecy jurisdictions are a core part of the problem of grand corruption. But these jurisdictions are also widely used by well-known multinational companies, hedge funds, and politicians from across the global political spectrum, as recently documented by numerous leaks of confidential documents (eg Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Luanda leaks), and by intermediaries offering to facilitate the creation of secretive structures.

The index shows where the opportunity for corruption exists, and how much this opportunity – when combined with the jurisdictions’ financial activity in the real world – can be translated into measurable risks of a broad range of problematic activities, not only corruption.

The structure of the Financial Secrecy Index

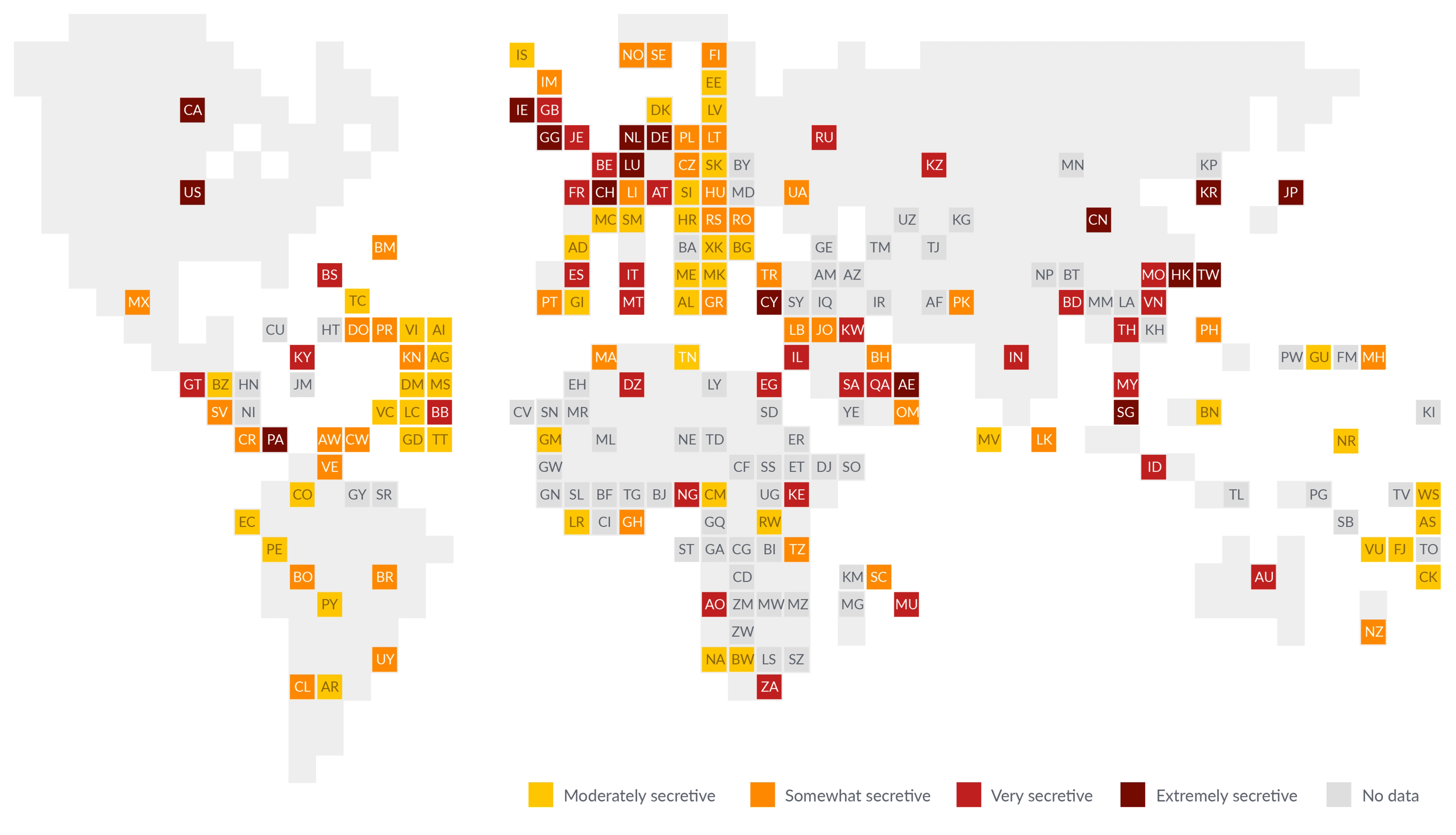

First published in 2009, the Financial Secrecy Index is a ranking of countries most complicit in helping individuals and legal vehicles to hide their finances from the rule of law. The index assessed 60 jurisdictions in 2009, and has expanded over time to include 141 jurisdictions in the 2025 update.

The index evaluates the degree to which a country’s legal and regulatory systems (or their absence) contribute to financial secrecy; this is the country’s ‘secrecy score’. This score is comprised of more than 100 questions, organised into 20 verifiable secrecy indicators, equally weighted. The score for each indicator ranges from zero (no room for financial secrecy) to 100 (unlimited scope for financial secrecy).

The index also monitors the volume of financial services each country provides to other countries’ residents – this is the country’s ‘global scale weight’. This value is based primarily on data from the International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments Statistics and is presented as each jurisdiction’s share of the global total of all cross-border financial services.

These two factors are then combined according to a cubic formula: multiplying the cube of the secrecy score by the cube root of the global scale weight (this ensures that the index gives more importance to secretive laws and regulations than to the volume of financial services in its evaluation). This calculation determines each country’s ‘FSI value’: the size of its role in enabling financial secrecy globally. Countries are ranked by FSI value.

Figure 1. Global complicity in financial secrecy

The secrecy score, a foundational component of the Financial Secrecy Index, evaluates the extent to which a country's legal and regulatory systems contribute to financial secrecy, enabling individuals and legal vehicles to hide their finances from the rule of law.

Signals of corruption

When secrecy scores are high – ie when countries have weak rules, poor implementation, or low cooperation with other countries – it signals a fertile ground for corruption and illicit financial flows. These flows are real and harmful: they reflect embezzled public funds, diverted aid, laundered bribes, and tax abuse on a global scale.

If one wants to understand the risks and exposure of an aid programme to corruption, it is not enough to look at local estimates of corruption levels. We need to consider the ease with which funds could be spirited away to other countries like Switzerland, Singapore, or Delaware. That is why integrating the Financial Secrecy Index into corruption risk assessments is crucial for practitioners, law enforcement authorities, and donors.

Three things the Financial Secrecy Index has revealed about transnational anti-corruption efforts

The index is used by banks to counter money laundering, by researchers to investigate the ways in which financial secrecy has managed to insert itself into everyday life, and by leading institutes to enrich their renowned indexes. (For more examples of the many practical applications of the index, see our June 2025 blog for the Tax Justice Network).

Used in these various ways, the index reveals three uncomfortable truths:

- Many of the most harmful secrecy jurisdictions are not small, obscure island nations, but rather G20, EU, or OECD members. The United States, Switzerland, and Luxembourg regularly rank near the top of the index – not because they are corrupt in the traditional sense, but because they sell secrecy services at scale. In other words, while some corrupt government officials in a certain country may represent the demand side of corruption, the Financial Secrecy Index reveals that many rich countries represent the facilitation side, providing financial secrecy that enables corruption while directly profiting from it.

- Financial secrecy is political. It is maintained not through inertia, but through active lobbying by financial and legal industries. The same countries that commit to transparency at the UN, OECD, or G20 are often led by politicians who block meaningful reforms at home, under pressure from lobbyists. And the laws that dictate this financial secrecy are not laws of nature: they are policy choices, and we can change them.

- Transparency reforms are often too weak to make a significant change. We’ve seen progress, in the automatic exchange of banking information, for example, but these systems often exclude the poorest countries and leave loopholes for powerful actors. We’ve seen progress in beneficial ownership registration – only to see a recent setback in the form of a ruling by the European Court of Justice after strong pressure from lobbyists and special interest groups.

Treating the symptoms of the commercial model of secrecy – such as focusing on individual cases, blacklisting specific jurisdictions, or prohibiting certain types of transactions – will not be enough. Real reform requires tackling the model itself by restricting the business of selling financial secrecy services.

Tracking the ‘escape routes’ of corrupt capital

The Financial Secrecy Index should be considered in every anti-corruption programme or risk assessment. It doesn’t give all the answers, but it asks the right questions: Who enables corruption? Where can the money go? What incentives do countries provide to attract the money and at whose expense? What rules are missing and where?

As the financial system becomes more complex – with crypto-assets, investment migration schemes, and new forms of wealth storage – we need to expand our view of corruption risks. Corruption is enabled and facilitated by the secrecy loopholes countries permit, either deliberately or by negligence. And the decision to allow financial secrecy in one country may spur corruption in another. The index helps us analyse this very issue. And with its new rolling update system, which ensures that legal reforms and regulations are promptly verified, incorporated, and reflected, it represents the most comprehensive and up-to-date resource tracking global financial secrecy.

For policymakers and practitioners, the message is clear: corruption doesn’t end at the border. If you want to counter corruption, start by closing the escape routes.

Anti-corruption measurement series

This blog series looks at recent anti-corruption measurement and assessment tools, and how they have been applied in practice at regional or global level, particularly in development programming.

Contributors include leading measurement, evaluation, and corruption experts invited by U4 to share up-to-date insights during 2024–2025. (Series editors are Sofie Arjon Schütte and Joseph Pozsgai-Alvarez).

Explore the other blogs in the series.

Sign up to the U4 Newsletter to get updates, or follow us on LinkedIn.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)