Blog

“How I think when I talk about anti-corruption: porridge and berries, priors and biases”

When we talk about anti-corruption we approach problems, and answers, from different perspectives or beliefs. This is normal, but I think these differences are under-examined and under-stated, and can make anti-corruption a bit of a virtuous ‘mush in the middle’.

We might be more effective if we put our cards – our ‘priors’ – on the table.

Anti-corruption as ‘porridge’: wholesome but uninspiring

Anti-corruption as a subject can be a bit like porridge: generic, grey, wholesome, homogenous. Our common enemy – corruption – is the opposite: diverse, multi-coloured, evolving, specialising, colonising new niches, transnational.

As a personal motivation, and for U4 – a relatively small organisation working in global anti-corruption – I aim not to just ‘make more porridge’. If I cannot say something additional, or different, I ask myself whether I (or we) need to say anything at all.

In his blog in December 2022, the World Bank’s Jim Anderson asked the Open AI Chatbot to tell him ‘why corruption is harmful for humanity’ and I think AI cooked up classic porridge:

Corruption is harmful for humanity because it undermines the rule of law and erodes public trust in institutions. It also distorts the economic and political functioning of a society as resources are diverted away from the most vulnerable, creating a cycle of poverty and inequality. Additionally, corruption reduces economic growth and investment, as investors are discouraged from investing in a country where corruption is prevalent. Moreover, corruption can lead to an increase in crime, as corruption often facilitates other criminal activities. Finally, corruption can lead to a lack of accountability, as those in power can use their influence to evade responsibility for their actions.

Jim noted ‘Okay, not bad. Fairly generic, but you could find something similar in the opening of hundreds of speeches and reports, including my own.’ Matthew Stephenson also set Open AI loose on anti-corruption and came to a similar conclusion. I agree; AI trains on human outputs, so the chatbot was really reheating the porridge of our own making. Like Jim, I have written things like this many times. Does it help us tackle corruption?

All of OpenAI’s points are correct, on average, in the long run. But almost every sentence could be challenged with a ‘yes but…’ – because there are major exceptions for every generalisation. Yuen Yuen Ang’s writing on corruption and China’s growth is one recent example that does not fit the generic long-run narrative, as she finds that not every form of corruption hinders economic growth.

Berries with our porridge

I like my porridge with berries (others may prefer raisins, nuts or chilies, depending on taste or culture) and I think the anti-corruption porridge needs a similar lift – acid, spice, challenge, nuance, new evidence, recognising and harnessing differences.

More ‘yes buts…’.

I have cooked and eaten plenty of anti-corruption porridge over the years. When I worked in Bangladesh nearly 20 years ago, aid donors tended to be moralistic and binary: ‘Bangladesh cannot prosper unless it ends corruption!’ This was at odds with the evidence even then. Yes, there was corruption, but there was also growth, investment, poverty reduction, human development.

Adding ‘berries’ risked souring the porridge, but was worth it. Bangladesh experts developed a more nuanced approach to understand how systemic corruption works, how good things can happen despite the bads, which bads were most damaging and why. As history (eg, see Naomi Hossain) tells us, Bangladesh has a complex development story, and binary, moralistic approaches to corruption have not aged well. Reality is more complex.

Beyond porridge: stating our priors

Being a ‘yes, but…’ person in anti-corruption can provoke exasperation, even anger. ‘Is the U4 Director saying that some corruption is not so bad?’

‘No, but…’.

U4’s work on ‘going beyond zero tolerance of corruption in aid’ is a good example of the importance of nuance if we really want to tackle corruption. This work resonates with exasperated practitioners in donor agencies and beyond who find ‘zero tolerance’ to be an impediment, or a charade. And it is proving valuable as donors commit to greater localisation and wrestle with the practical implications.

I am happy to put my own anti-corruption cards on the table. To borrow a term from statistical analysis – we all have different ‘priors’ – the beliefs or uncertainties that we hold before we come to our ‘data’ (or problem). There is a useful tradition of ‘stating your priors’ before commencing analysis, to reduce the risk of bias.

In anti-corruption I think we would benefit from thinking about and ‘stating our priors’. We should not judge those who have different priors, but accept that we may be coming from different perspectives and use this to spark constructive debate. More berries.

Sometimes our priors feel at odds with dominant voices. I experienced this at the International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC) in late 2022. It was a good week, particularly the opportunity to learn from the diverse views of people I met between sessions, rather than the official conference business. This was not unexpected as I ‘know my priors’ and try to understand what drives others in anti-corruption. Dan Hough wrote this blog about what he liked at IACC and noting some gaps (research, discussion of power/politics, money). I agree with him. I eat my porridge with added evidence and politics.

My ever-changing priors

My priors keep evolving. To misquote Groucho Marx: ‘Those are my principles, and if you don't like them... well, I [will soon] have others’.

I began my working life in public health research, then was a country adviser in DFID. My priors were largely principle and value driven – a commitment to reducing bad stuff – disease, poverty, inequality, violence, corruption (priors v1.0).

But I learnt that being against bad things was not sufficient – I worked on projects that were value driven but ineffective, including in anti-corruption. I revisited the benefits of evidence-based policy and practice (prominent in my work in public health) and tried to apply these to governance. This included commissioning research where evidence was thin. I updated my priors (v2.0) – ‘evidence in support of my values’.

But the messy real world kept getting in the way of evidence-based policy and I saw the benefit of weaving in a rigorous understanding of context, power and politics (what I call ‘practical political economy’). So ‘evidence based’ became ‘evidence informed’, as people with power – be it governments, elites, social movements, politicians, donors – do things that are contrary to the evidence and serve other ends – good and bad. Priors v2.1.

Priors, biases and assumptions are not just for individuals though – it’s important for organisations to address them, too. When I worked on DFID’s Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) research programme, for example, we were up front about priors, describing these in ‘the ACE principles’:

- Anti-corruption (not just admiring the problem)

- Problem focused (not generic solutions)

- Take politics seriously (not just technical approaches) and target politically viable reforms

- Measure the effects of anti-corruption interventions

- Engage policy and practitioners from the ‘nose to tail’ (beginning to end) of the research process

These evolved (for example, into see ACE principles for Serious Organised Crime – SOC ACE) but generally still hold.

So, what are my priors in anti-corruption now? (I have lots!)

At U4 we are a diverse team of experts and we all have our own set of priors. I think it is good to get these out on the table and explore differences.

My own ‘everyday’ priors include a skepticism about purely value-driven approaches; acceptance that corruption can sometimes help solve everyday problems for some vulnerable people; frustration with ‘reheating the porridge’ (see AI Chatbot above); and aversion to promotion of ‘best practice’ that has not been independently tested. ‘Best practice’ without evidence is ‘practice’.

So, at the IACC, discussions where panelists restated how bad corruption is, made value-driven statements and agreed with each other, felt a bit ‘porridgey’. But this reflects the ‘priors’ of others and I try to find common ground, or ask a constructive question that reflects my own priors (calling panel organisers: please make space and time for ‘berries’). And I invite all to come and challenge me in the grumpy, jaded coffee lounge.

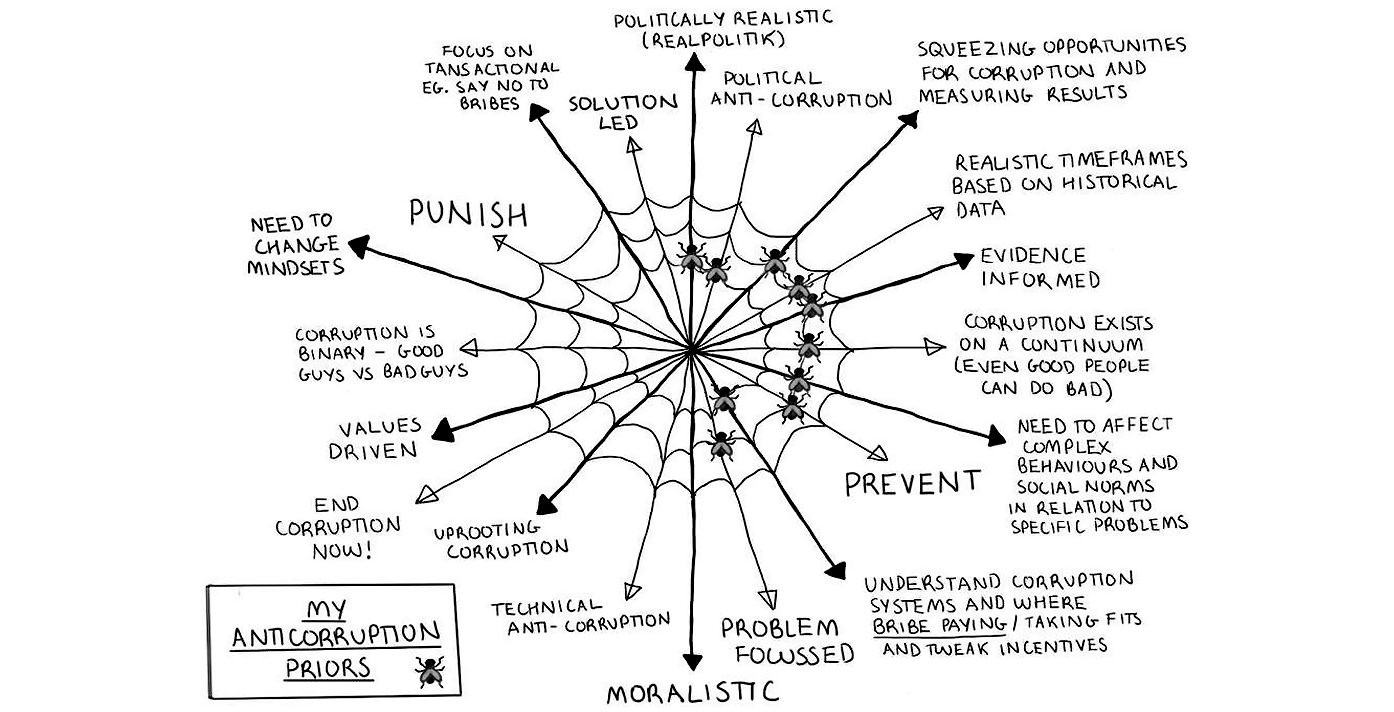

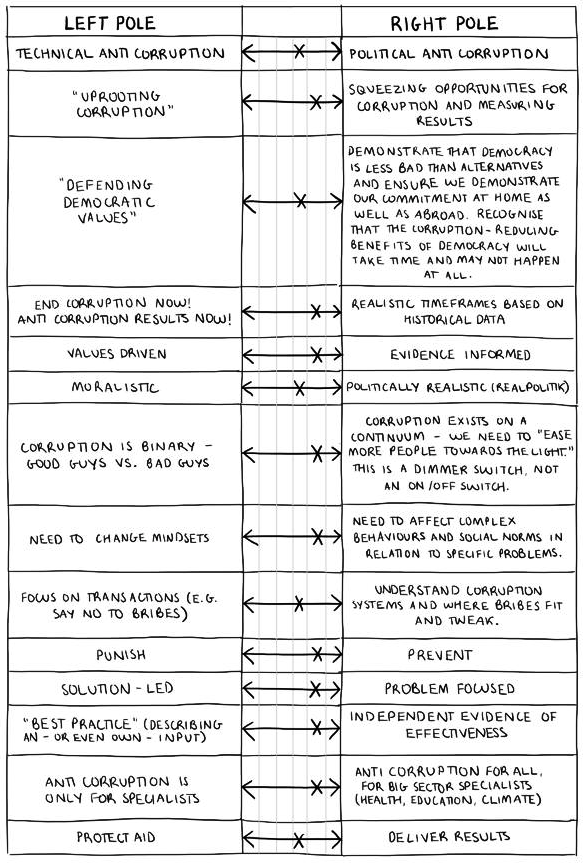

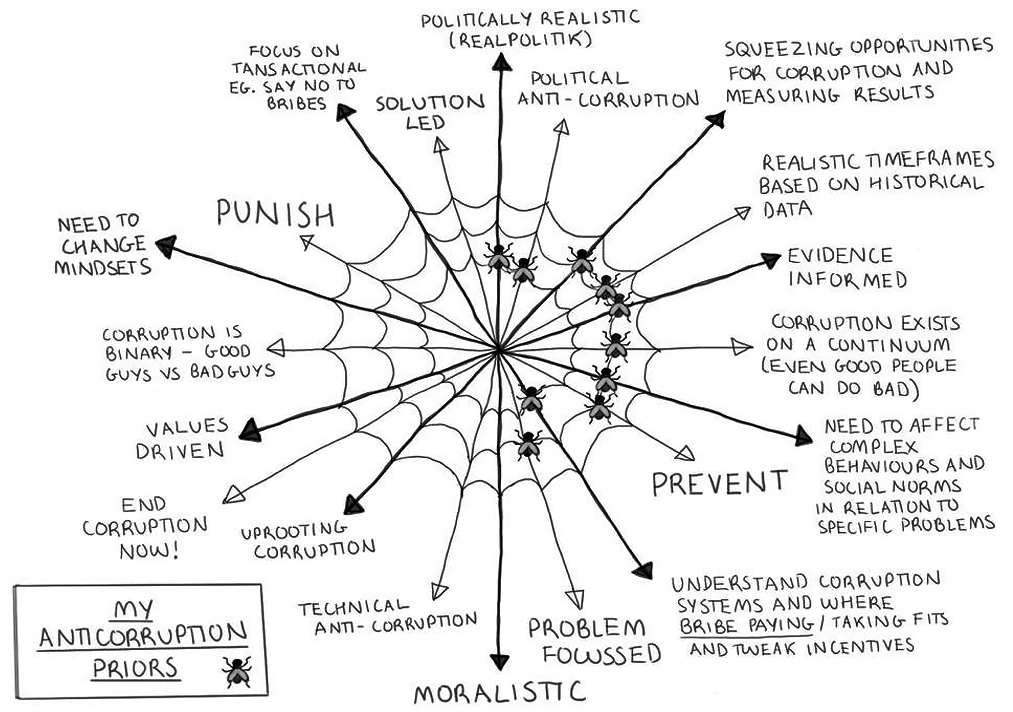

Thinking harder, I plotted my anti-corruption worldview along various axes, marking ‘X’ for the position of my priors on each. None of the Xs are at an extreme pole, and may move over time (I try to be open to influence).

But I am aware that some of my labels on the right are my adverse reactions to statements or positions (on left) that I don’t agree with, and I may unfairly mischaracterise these, or set them up as ‘straw people’ to knock down. This table is work in progress – I’ll work on a more objective version with U4 colleagues.

Table. A quick sketch of my anti-corruption worldview

(Download this table as a PDF)

Credit: Hamsiidris by-nc-nd

The table looked dull, so I sketched the axes crossing each other. My daughter thought it looked like a spider web, and she drew it as one. My ‘priors’ became flies. I like graphics and think that they can help engage others (my priors). But others may think this trivialises a very serious subject (their priors…).

Figure. My anti-corruption 'priors', biases and assumptions, plotted as a web

Credit: Hamsiidris by-nc-nd

My priors need a bigger t-shirt

My priors don’t lend themselves to snappy slogans, but I think that is the reality of nuanced, evidence-informed public policy (another prior here: I learnt – from the unintended consequences of Nancy Reagan’s Just say no! campaign against drugs – that messages can become too simple). I understand why we have simple slogans to rally around, but we should not confuse these with effective behaviour change communication (ie, challenging other people’s priors).

I am aware that my priors risk distorting anti-corruption initiatives. I am director of an anti-corruption organisation, so my biases may carry some weight. But better to be open about these than ignore them.

Over to you

So, what are your priors? Worth setting them out? Put some berries in the porridge? Some flies in your web?

If this blog annoys you, or you think the porridge or spider’s web trivialise a very serious subject – that’s the point! What does this tell you about your priors?

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)