A policy approach to the politicisation of corruption

Where corruption is politically embedded, anti-corruption efforts are constantly at risk of facing pushback and unintended consequences, or of being ineffective. To avoid these risks, we suggest a two-pronged approach revolving around direct anti-corruption interventions and more indirect accountability reforms. See U4 Issue Tuning in to the politics of (anti-)corruption: astute interventions and deeper accountability’ for more details.

Direct anti-corruption efforts

Direct anti-corruption efforts involve targeted action on specific corruption risks and challenges. To avoid subversion by political actors, direct interventions need to become highly targeted, bottom-up, and chosen according to the viability of local political conditions, rather than due to donor preferences or preconceptions of what anti-corruption should look like. To do this, practitioners should:

Target the most feasible areas

Integrity-building programmes can be more effective by concentrating on sectors or areas of public administration where anti-corruption does not threaten the interests of power-seeking political actors and where there is some support – from citizens, businesses, or other groups – to push forward reforms. The Anti-Corruption Evidence consortium led by Mushtaq Khan and his team at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London said that, for anti-corruption strategies to work, they must be feasible to implement.

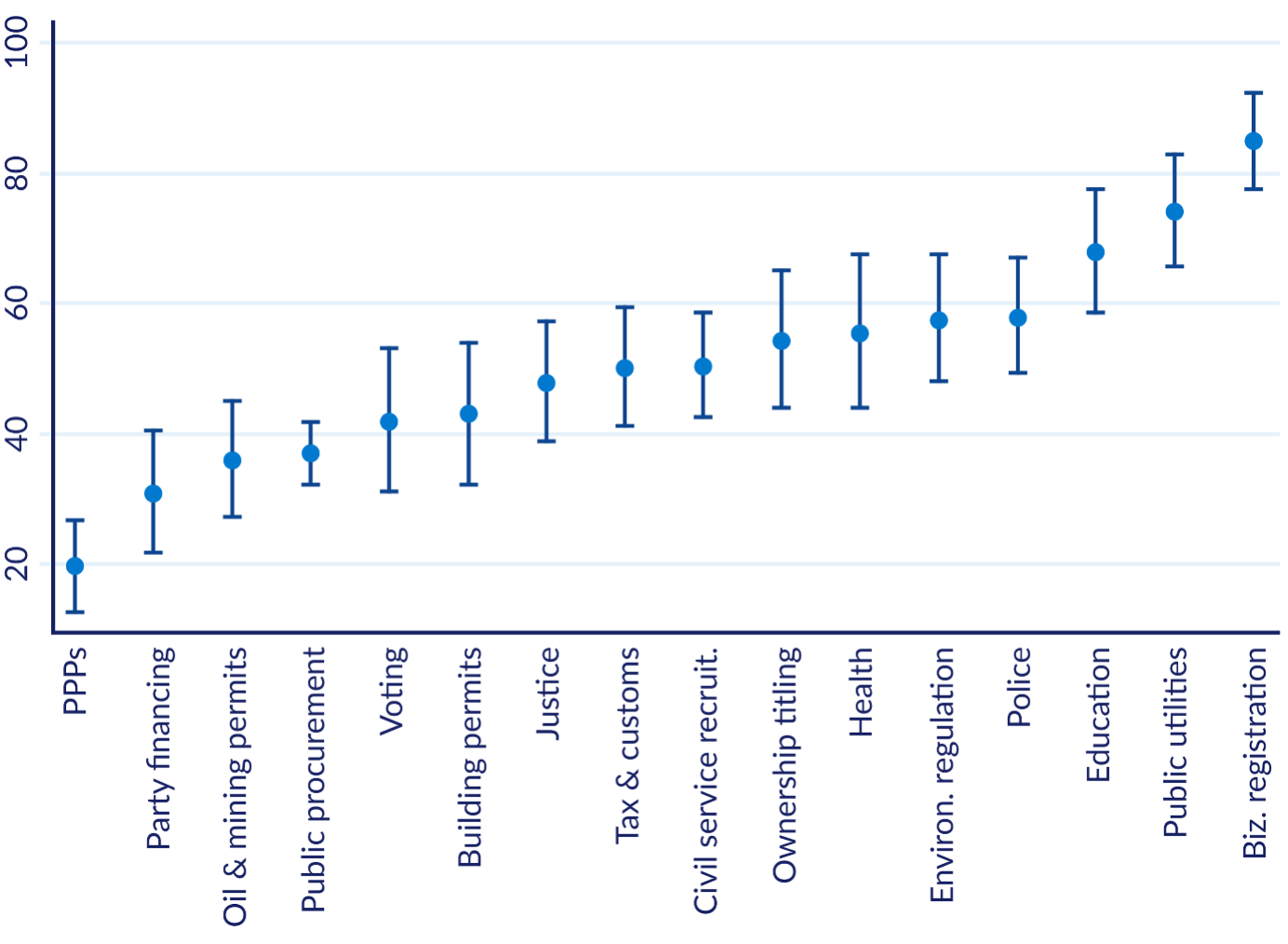

Taking its cue from that emphasis, a U4 analysis by Uberti (2020) assesses whether an anti-corruption practice is either central or peripheral to the political stabilisation strategies used by political elites in Albania. Through expert surveys, the aim was to identify where organised opposition to reform was likely to be low enough to make reform feasible. The feasibility ratings are presented in Figure 1 below. The sectors believed to be most amenable to anti-corruption interventions include education, public utilities, health, and environmental regulation.

Figure 1: Estimated feasibility of anti-corruption interventions in Albania, by sector

Source: Uberti, 2020.

Mobilise the winners of reform

Identifying a reform area that is politically viable is not enough; even sector-specific reforms can face pushback. And so, another important task for practitioners is to understand the political dimensions of particular sectors or subsystems. This can help galvanise actors and generate the core ingredients for reform: legitimacy to change, influence over others to make changes, and a capacity to expand a network of supportive actors.

Groups must be motivated to ‘keep up the pressure’. Mushtaq Khan and colleagues stress how these kinds of coalitions can spur horizontal enforcement of reforms. The Building State Capability faculty at Harvard University describe this as being about initiating, maintaining, and growing an ‘authorising environment’ for reform.

The heart of these strategies is about mobilising those who gain from reforms – that is, those who lose from corruption. Practitioners should identify who may win from reform, and who has the influence to change specific issues. Successful strategies do not always depend on persuading those in high office; critical mass can also shape action.

Build new forms of capacity

Coping with the politics of anti-corruption also requires skills and capacity that may involve unorthodox forms of support. One form of skill-building could aim to enable practitioners to take more adaptive approaches that include greater flexibility and emphasis on ongoing learning that may be better suited to cope with ‘political surprises’ as reforms play out.

An Open Society Foundations report on seeing new opportunities within anti-corruption identifies further key areas of support relevant for coping with the politics of anti-corruption. As political backlash is a risk, one area of aid can go toward reinforcing care and protection structures. Interventions could provide resources for digital, physical, and psychosocial security.

Funding peer self-help networks can help sustain reforms in the face of opposition, providing solidarity, resilience, information-sharing, and a sense of mutual care for members. The Corruption Hunter Network, a solidarity group for anti-corruption legal professionals supported by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), is a globalised version of such a network. A U4 study on networks of anti-corruption authorities suggests that there is scope to improve these kinds of peer networks.

Developing accountability constraints

In addition, efforts are needed to help support political accountability. The aim is to build up sufficient answerability and sanctions so that corruption is squeezed out of politics. In countries with a credible rule of law and with committed political leadership, then conventional accountability institutions – the judiciary, parliament or other oversight institutions – should be supported as a priority. Yet, in contexts of high politicisation, these accountability measures could clash with ruling elites’ interests. We suggest alternative and more realistic approaches that can align with politicians’ incentives.

The list below summarises the policy options. These are meant as initial possible options, and their viability should be assessed country to country. They are based on the key criteria that there is empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of these interventions to build accountability and ultimately control corruption. We organise the options into three building blocks of accountability: access to information; new forms of collective action; and smart sanctions.

- Purpose:

Access to information

Aim:

More equitably distribute information about the workings of government.

Types of reforms:

– Support free press through promoting press plurality and economic sustainability.

– Support internet access and online spaces for social collaboration.

– Digitalise public services so that decision-making can be tracked. - Purpose:

New forms of collective action for the economy, public services and representative organisations.

Aim:

Overcome the reasons why social groups do not organise for more accountability to generate stronger collective pressure for more accountability.

Types of reforms:

– Collectively organise business around formal associations.

– Develop trust in key public services through long-term investments in nurturing strong leadership and management.

– Help political parties develop programmatic agendas. - Purpose: Develop smart sanctions.

Aim: Stronger sanctions mean corrupt actors may self-restrain and norms around accountability standards become internalised.

Types of reforms:

– Support the development of pro-integrity social norms, so that corrupt behaviour is socially sanctioned.

– Support domestic and international sanction regimes and frameworks.

Building accountability suggest a multi-sectoral agenda for anti-corruption: practitioners need to connect with other government departments, they need to be involved with those promoting democracy, as well as sectors such as welfare, media support, ICT, and infrastructure development. These practices are not about short-term programmes. Many of the options imply incremental approaches but require long-term and credible backing.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)