The nature and roles of legal empowerment

Legal empowerment (LE) is the use of laws and rights specifically to increase relatively powerless populations’ control over their lives. In short, it means helping people to know, use, and shape the law. Legal empowerment builds people’s capacities and power to improve their lives, such as by elevating and protecting their income and assets or gaining greater access to health and education services. This may involve combating corruption, in both explicit and implicit ways, as corruption is often an obstacle to such goals.

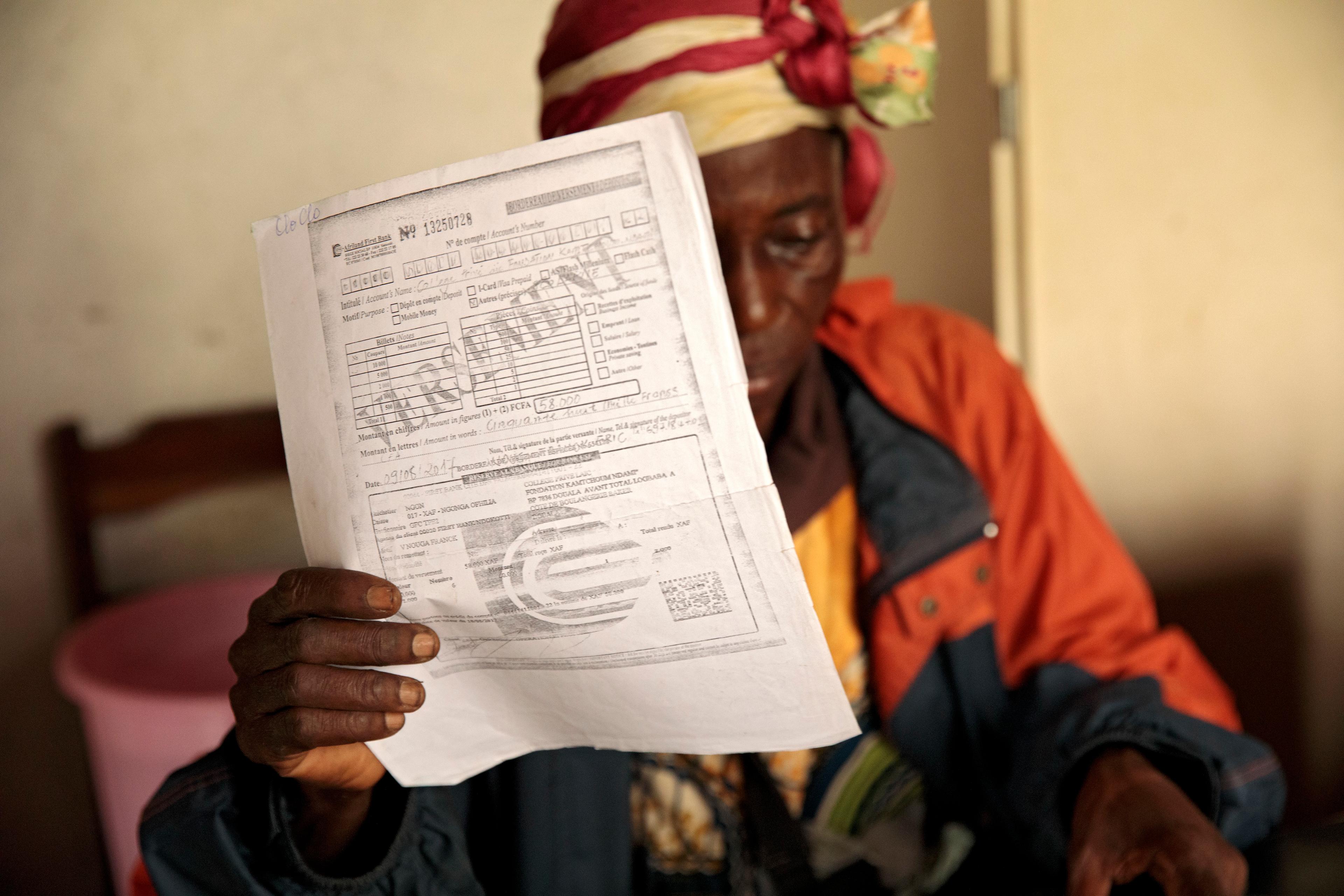

Legal empowerment includes people taking their cases to courts of law, to administrative bodies, to land, labour, and housing tribunals, and to traditional justice systems, among other venues. But it also can involve enforcing people’s rights through social accountability processes that seek to monitor and otherwise influence public officials and public services. Thus there is substantial (although not complete) overlap between legal empowerment and social accountability interventions.

Moreover, LE is partly about law reform. That is, it can equip people to advocate for and secure changes in laws, rules, systems, and regulations that will improve their ability to exercise their rights and live better lives. Legal empowerment is therefore a broader concept than legal aid or legal services, which largely work within the confines of existing laws. LE has prominent power and sometimes political dimensions – helping people gain more control over their lives – that do not figure as centrally in legal aid.

Civil society organisations are leading promoters of legal empowerment activities, although government agencies can also play a role. Civil society LE efforts can constrain corruption even in the absence of reliable state institutions, and may help bring about somewhat more functional and accountable institutions.

LE plays an increasing role in the programmes of international development institutions, although this role is often implicit. This applies to many initiatives that are undertaken in connection with sectors such as justice, local governance, education, health, and natural resources.

Impact on corruption

There is strong evidence that LE interventions can help constrain corruption in service delivery and government operations, as well as advance accountability in other ways. LE activities can involve community organising, mobilising media, and strategic efforts to engage key officials. Case studies suggest an impact on corruption in multiple fields, as reflected in the examples below. It should be noted that LE principally affects petty rather than grand corruption.

Education. Local committees working with the Uganda Debt Network monitored the implementation of Uganda’s Poverty Action Fund. Community monitors detected poor-quality construction of classrooms, as well as embezzlement of public resources. As a result, the government moved to strengthen public accountability in school construction.

Public health. A study of a social accountability programme focusing on maternal health in Uttar Pradesh, India, found that a modest intervention – informing women of their rights and how to lodge complaints – yielded substantial results. The initiative reduced bribe-taking that had been imposed on women when they were informally and illegally charged for health services that should have been free.

Social safety nets. Under the Citizens Against Corruption programme in Bangalore, India, 15 projects by civil society organisations countered corruption in the provision of social safety net benefits. A programme evaluation found that almost all of the grantee organisations were helping people receive rations, job cards, and other benefits without having to pay bribes.

Multiple public services. The Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Program (SERAP), a Nigerian NGO, helps partner populations use Nigeria’s Freedom of Information Act to access public information about health, education, and water services provided by local and state authorities. SERAP also helps people file complaints with anti-corruption institutions.

Legal systems. In Liberia, the Community Justice Advisor programme helped clients secure implementation of a 2003 law that granted inheritance rights to women.

Democratic governance. Providing the public with information about corruption on the part of local politicians in Brazil decreased the re-election chances of reportedly corrupt officials.

Recommendations for donors

Donors should support legal empowerment as a multifaceted means for constraining corruption and otherwise strengthening justice services or service delivery in other fields, often in the context of sector-specific programmes such as health or education. Donors can support:

- LE work, particularly by civil society. NGOs and other civil society actors merit political and financial support for their LE anti-corruption initiatives, especially since their LE efforts are generally more creative and effective than those of government agencies.

- LE endowment funds. To help ensure sustainable, independent anti-corruption efforts by civil society, donors and other funding sources could establish politically independent LE endowments.

- Training for government personnel on LE. Donors can support governments to proactively train their personnel to welcome rather than resist cooperation with the populations they serve, and with the civil society elements that work with these populations to curb corruption.

- Complementary support for media. Support for media and for investigative journalism in particular – sometimes in combination with LE, sometimes separately – could prove to be fruitful arenas for combating corruption.

- A robust research agenda. Funding agencies can support quantitative and qualitative studies to document the progress, impact, and lessons flowing from LE efforts to constrain corruption.