Harnessing legislative advocacy to advance the anti-corruption agenda in Colombia: Opportunities and challenges

In democratic systems, civil society plays a significant role in the approval and repeal of laws. In Colombia, the advocacy activities carried out by civil society organisations (CSOs) around the legislative process have led to the incorporation of new topics in the legislative agenda and provided strategic inputs to strengthen the discussions on various bills.

Since 2021, Transparencia por Colombia (TpC) has been implementing the Anti-Corruption Legislative Agenda (ALA), an initiative that aims to combat corruption through legislative advocacy. As part of this effort, TpC has:

- Promoted citizen oversight of congressional activities to monitor anti-corruption efforts and identify corruption risks within bills

- Disseminated recommendations to strengthen all types of bills by incorporating an anti-corruption approach, which is based on their knowledge and expertise in the prevention, control, and sanction of corruption in Colombia

- Provided technical input on how to prioritise and mainstream anti-corruption in structural or sectoral bills, particularly those related to access to goods and services

The advocacy strategy, which is constantly being tailored to the particular dynamics of Colombia’s legislative context, has enabled TpC to establish itself as a technical partner to Congress.

As an anti-corruption-specialised CSO, TpC actively seeks opportunities to impact bills across various sustainable development topics – not just those directly related to addressing corruption. TpC views legislative advocacy as an alternative for advancing anti-corruption mainstreaming, as laws can lead to significant structural changes in a country.

This Practice Insight focuses on outlining the windows of opportunity and challenges experienced by TpC when conducting anti-corruption legislative advocacy in two crucial bills for the country: the National Development Plan 2022–2026 (NDP) and the National Health Reform (the ‘Health Reform’). The former defined the guidelines and priorities for President Gustavo Petro’s four-year term; however – due to the Colombian legislation – it must be approved as a law, and thus must complete the bill process. The latter aimed to structurally modify the country’s health system.

In both cases, the advocacy efforts yielded mixed results. For the NDP, although most of TpC’s recommendations were not adopted, its advocacy led to the approval of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS) – a structural measure aimed at addressing corruption across all sectors and levels. In the context of the Health Reform, despite limited influence on the bill’s drafting, TpC effectively highlighted the need to incorporate an anti-corruption approach into health-sector discussions. By partnering with experts and health-focused CSOs, TpC successfully changed legislators’ mindsets, recognising that these measures were crucial for ensuring the proper functioning of the system and, consequently, safeguarding the right to health.

Although the analysis presented is specific to the Colombian context – where the NDP must be debated and approved by Congress (same process as any other law) and reviewed by the Constitutional Court – its findings can be extrapolated to other countries with democratic systems based on participation and representation. This paper will benefit: 1) CSOs interested in engaging in anti-corruption legislative advocacy or strengthening their efforts in this regard; 2) members of Congress and national government officials interested in identifying and creating spaces for CSOs’ participation in the legislative process; and 3) governments, cooperation agencies, and other donors interested in CSOs’ legislative advocacy as a strategy to combat corruption.

This Practice Insight begins with a brief description of the methodology used for its preparation, as well as the role of CSOs in the legislative process in Colombia. Then, it outlines TpC’s experience in both case studies – the NDP and the National Health Reform – with special emphasis on the opportunities, challenges, and strategies to advocate for anti-corruption mainstreaming in these bills. It concludes with some recommendations for CSOs, donors, members of Congress, and government officials involved in the discussion of bills, to strengthen anti-corruption legislative advocacy efforts.

Methodology

This Practice Insight is based on TpC’s experience with its ALA initiative, as well as on the information collected through semi-structured interviews and collective discussion spaces with members of Congress, public officials from the health sector, experts, community-based organisations (CBOs) in the health sector, and cross-sector CSOs (eg health, democracy, governance, human rights, and citizen participation) that have engaged in legislative advocacy.

Between February and March 2024, seven semi-structured interviews were conducted to characterise the role of civil society within the NDP and the Health Reform (see Table 1).

Table 1: Details of interviewees

|

Actor |

Number of interviewees |

|

Health-focused CBO |

1 |

|

Member of Congress with an active role in the bills under study |

2 |

|

Public official from the health sector |

1 |

|

Expert in the health sector |

2 |

|

Health-focused CSO |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

7 |

In mid-March 2024, a nine-member focus group – which comprised representatives from five CSOs actively engaged in the legislative activities of congress – convened. The discussion revolved around good practices, challenges, and strategies when conducting legislative advocacy. The topics addressed were:

- The role of civil society in the legislative process

- The opportunities, strategies, and challenges identified to impact legislation

- CSOs’ response to conflicts of interest of members of Congress and lobbying

- Lessons learned and opportunities for improvement, to increase the possibilities to impact legislation

The role of civil society in the legislative process in Colombia

TpC adopts the definition of CSO presented by the Organization of American States (1999): ‘any national or international institution, organisation, or entity made up of natural or legal persons of a non-governmental nature’. Aligned with this definition and the research conducted, CSOs involved in legislative advocacy in Colombia can be classified into three categories (see Table 2).

Table 2: Civil society categories

|

Types of CSOs |

Main work |

|

Grassroots |

Various citizens’ associations that are formed around specific needs. The common interest may be territorial, social, or sectoral. Examples of such associations include: community organisations, citizens’ oversight bodies’, and trade unions. |

|

Academic and technical |

Organisations involved in research and knowledge generation of a technical and scientific nature. Examples include think tanks specialising in health, peace, economics, and corruption, and academic research centres. |

|

Corporatised |

Organisations that carry out research and advocacy to protect private interests. Examples include health industry associations and trade union organisations. |

The research suggests that, regardless of the category to which they belong, CSOs in Colombia primarily play the following roles in the legislative process:

- Consultative: During public hearings or forums, contributing technical comments on the bills under discussion or on issues addressed in the participation space

- Technical assistance:Providing theoretical inputs to enhance the objectives, scope, and articulation of bills, as well as the discussions around them

- Monitoring and oversight: Monitoring the progress and content of bills that are of interest to them

- Awareness raising:Conducting educational activities to provide citizens with information about the functioning of Congress and some specific bills

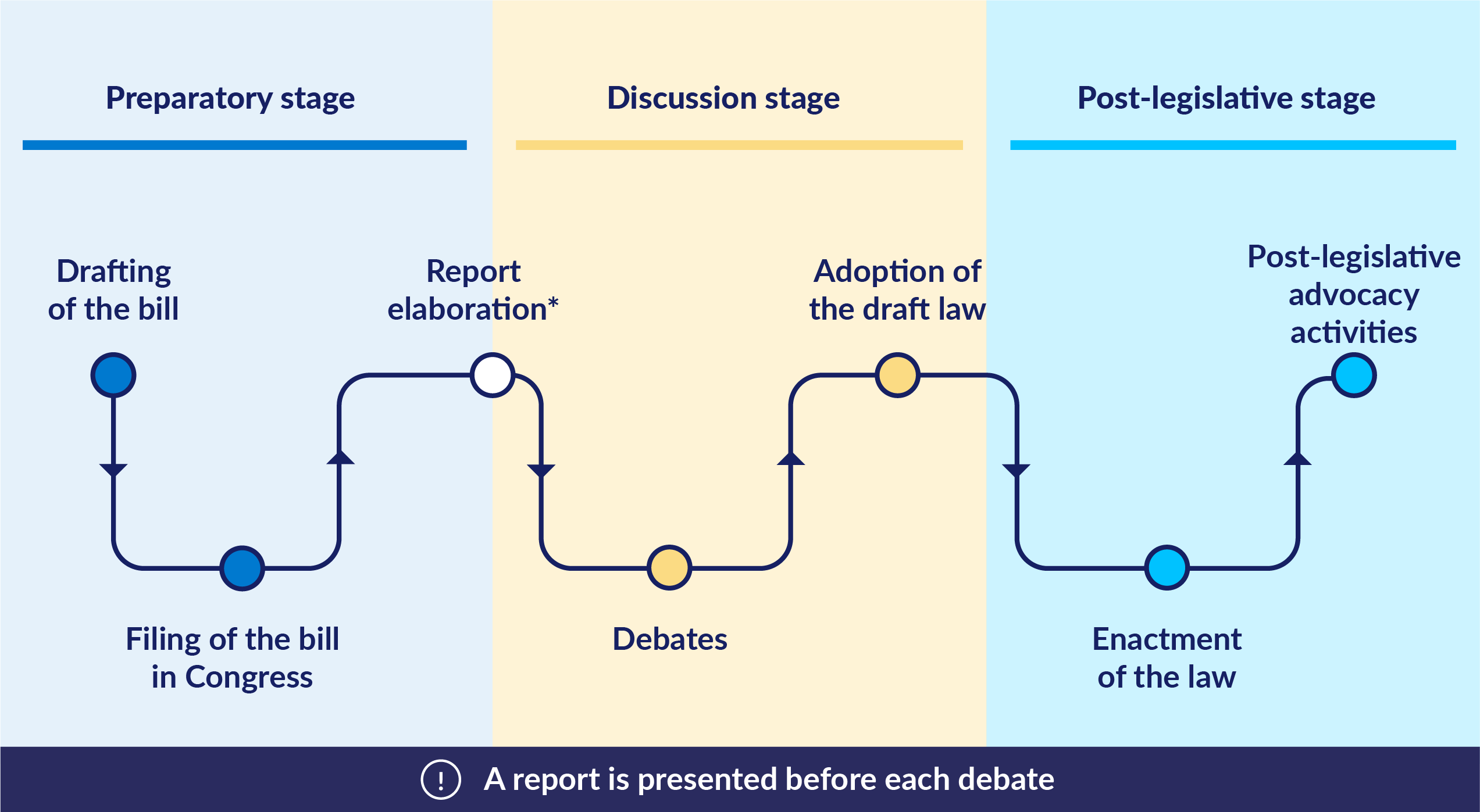

Although CSOs can assume a variety of these roles during the legislative process of the bills they are interested in (see Figure 1), their impact can vary significantly based on their capacities, experience, and relationships with members of Congress and government officials involved with a bill. As one of the members of Congress interviewed observed ‘some actors have more power than others to be heard, increasing their possibilities to impact legislation’.b142f23c78cb

Figure 1: Phases of the legislative process in Colombia

The research indicates that the impact of CSOs on a specific bill depends on both internal and external factors. External factors include the country’s current situation and the willingness of the sponsors of the bill and the members of Congress to engage with CSOs. Internal factors include the CSO’s location (urban or rural); political affinity; knowledge of specific issues; established relationships; and the available technical, human, technological, and material resources.

Nevertheless, to increase the chances of impacting a specific bill, it has proven effective to identify the windows of opportunity that may arise during its legislative process and, based on them, employ the most suitable strategies and tools to achieve the desired advocacy goals. Strategies can range from organising discussion spaces related to a bill, to raising awareness through social media to engage citizens.

Another factor to be considered when analysing the role of civil society in the legislative advocacy – and which has been identified as a desensitising factor – is the risk for the CSO to be instrumentalised by the members of Congress and public officials who try to impose certain agendas or policies on them, or for them to to be misinterpreted as lobbyists. This risk should be considered by the CSO both in the process of developing a legislative advocacy and in all its advocacy activities.

TpC’s anti-corruption legislative advocacy work in the legislative process of the two case studies – the NDP and the National Health Reform – illustrate the opportunities, challenges, and obstacles CSOs face when conducting anti-corruption legislative advocacy.

The National Development Plan 2022–2026

From November 2022 to May 2023, TpC conducted legislative advocacy to strengthen the NDP by incorporating an anti-corruption approach and adjusting the proposed measures to mitigate corruption potential risks in implementation. Within the ALA initiative, they took advantage of different avenues, such as creating and participating in collective spaces, conducting bilateral dialogues, and involving the community through social media.

Even though not all recommendations made to the NDP were included in the draft law approved by Congress in May 2023, TpC achieved significant wins, especially ensuring that the national government committed to establishing a National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS). Additionally, this experience provided several lessons, including the need to always be prepared, targeting messaging to the interests and needs of congressmen involved in discussing and approving the bill, being flexible, and developing a solid and ongoing communication strategy to capture public attention throughout the whole legislative process.

This section provides an overview of the NDP, outlines the opportunities that were available for CSOs to impact the bill-drafting process, and presents the results of TpC’s anti-corruption legislative advocacy strategy.

What is the National Development Plan and who is involved?

In Colombia, the NDP is a comprehensive policy framework that outlines the country’s strategic priorities and development goals over a four-year period, coinciding with the presidential term.99fbff243935 It serves as a roadmap for the government’s economic, social, and environmental policies, setting specific goals, targets, strategies, and budget for both the short- and mid-term.

For its drafting, the government – represented by the National Planning Department – consults with the National Planning Council and the Territorial Planning Councils, which represent various sectors of society and act as advisor bodies in this process. The resulting bill must be completed within a maximum of six months from the moment the president takes office.

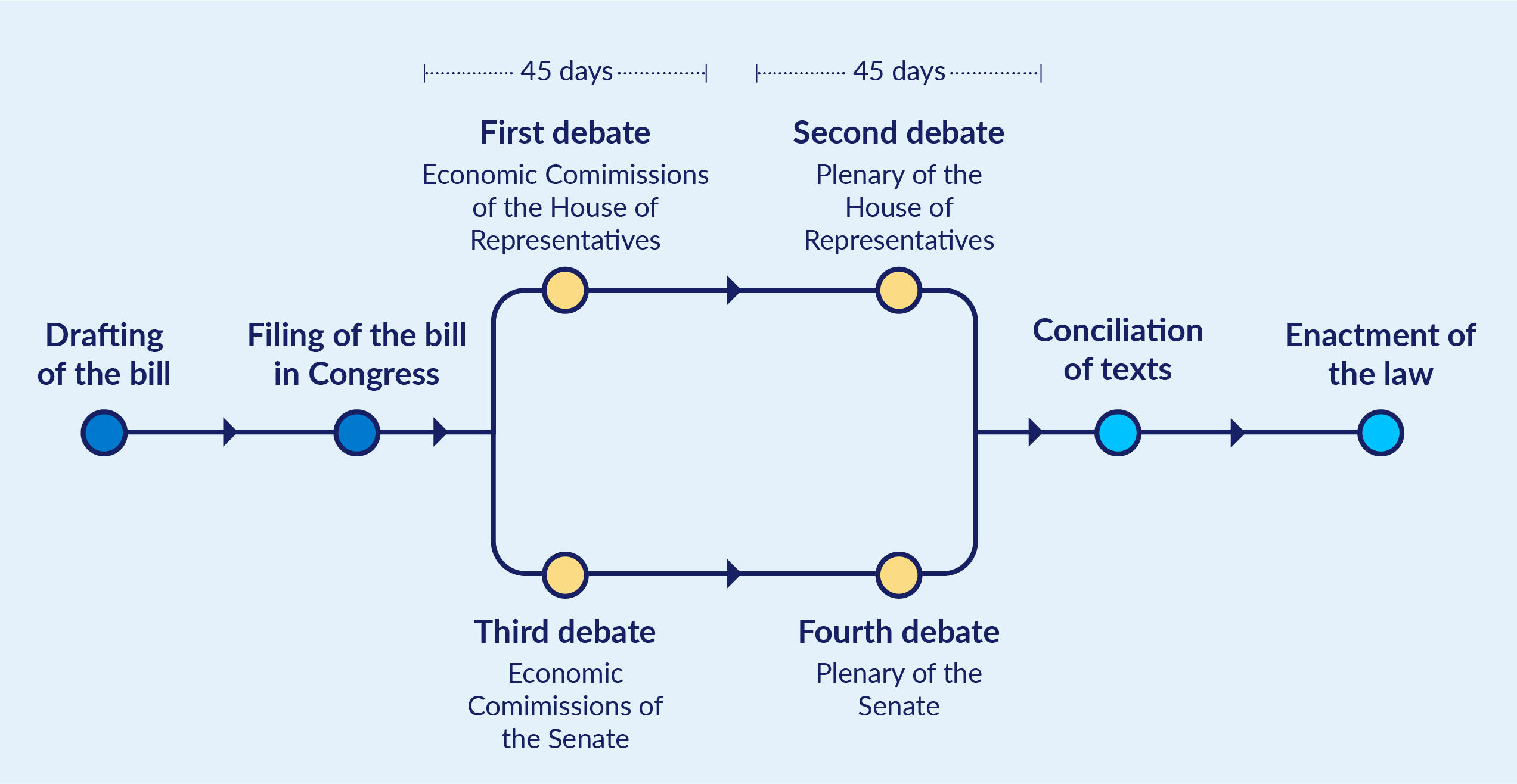

The NDP must be approved within a maximum of three months after the government submits the bill to Congress. The economic commissions of both the Senate and the House of Representatives conduct joint debates on the bill, followed by separate yet simultaneous debates in the plenary sessions of each chamber. Figure 2 illustrates the legislative process.

Figure 2: Legislative process of the NDP

Congress cannot modify the core aspects of the project unless it has the endorsement of the National Planning Department. Consequently, advocacy efforts on the NDP should target not only members of Congress but also the government officials from the principal ministries and presidential agencies to which the NDP assigns specific functions and responsibilities.

Anti-corruption commitments in the NDP: A minimal and disjointed approach

In February 2023, President Gustavo Petro submitted his NDP proposal to Congress.f357b75f7320 It was an extensive document that included ambitious goals and policy guidelines to address deep-rooted social, economic, and environmental issues.b5ae6dcb982d Although Petro’s campaign proposals included several related to combating corruption,18ed1ed47079 the anti-corruption measures included in the NDP were minimal, disjointed, and lacked clear strategies to address corruption effectively.4137dc187267 For example, it included measures to enhance citizen participation in public management and strengthen environmental information systems. However, it lacked clarity on the public entities responsible for their implementation, the sources of funding, and how these measures would integrate with the existing efforts.bca1e19abfd3 In summary, the NDP did not provide a comprehensive strategic approach to combating corruption, failing to address it as a structural problem involving multiple sectors and levels.

Public participation spaces in the NDP’s legislative process

In developing the NDP, the National Planning Department convened 51 Binding Regional Dialogues across the country to collect citizens’ concerns, expectations, and proposals. The prioritised topics were territorial planning, human security and social justice, the right to food, productive economy for life and countering climate change, and regional convergence to address socio-economic disparities between regions.ff8bd1720405 In total, 250,000 people participated; 14,383 needs for change were identified; and there emerged 22,945 proposals to be included in the NDP.684af2609c89

During the discussion of the bill, since neither Congress members nor the National Planning Department organised spaces of public participation, CSOs held their own to continue strengthening the bill by providing concrete observations and recommendations. CSOs also sent their concerns and recommendations to the aforementioned actors via email, and used press and social media – primarily X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram – to inform and engage the public. Involving the public was expected to apply pressure on Congress members to adopt the proposed changes, thereby enhancing the CSOs’ possibilities to impact the bill-drafting process.

Following the bill’s debates and the conciliation of the texts resulting from the Senate and the Chamber of Representatives, the President signed it into law on 19 May 2023. From then on, strategic litigation became an attractive option for some CSOs to, for example, advocate for the removal of certain articles of the resulting law.

TpC’s strategy

TpC conducted advocacy activities across all three phases of the legislative process: preparatory, discussion, and post-legislative.

Preparatory phase

The Binding Regional Dialogues949020b20511 aimed to foster civil society participation. However, among the topics prioritised for discussion, there was no reference to the phenomenon of corruption.0fd23d96f8f8 Furthermore, since there was no broadcasting of the dialogues, there is no evidence that the anti-corruption initiatives were discussed in some of the sessions. This posed a significant obstacle for CSOs working on anti-corruption issues, as they were unable to provide proposals on the matter. To address this issue, TpC – along with other CSOs – decided to send documents containing observations and proposals via the official institutional emailof the National Planning Department.

TpC’s recommendations emphasised incorporating an anti-corruption perspective in the NDP, including:e0a37d4c262e

- Formluating and implementing a national strategy to address corruption

- Strengthening the existing institutional anti-corruption architecture by establishing a National Anti-Corruption Agency with budgetary and administrative autonomy, responsible for organising, coordinating, and leading the government anti-corruption efforts, while facilitating collaboration with other branches of power

- Enhancing public management processes related to access to information, budgeting, employment, and public procurement

- Mainstreaming anti-corruption strategies in priority sectors and systems, such as the political system, Peace Agreement implementation,41873e21190f beneficial ownership transparency, extractive industries, the private sector, defence, and environmental sectors

Despite TpC’s efforts, the National Planning Department did not provide a response.

Discussion phase

In February 2023, the government presented the NDP bill to Congress. From that point on, anti-corruption legislative advocacy expanded to include a new target actor: members of Congress, who were now tasked with conducting the legislative process and approving the bill within 90 days.

In addition to mapping changes from the document outlining the foundations of the NDP to the bill presented to Congress, TpC identified positive aspects and measures that could help enhance anti-corruption commitments, as well as gaps or deficiencies in the text.

This mapping exercise was crucial for ensuring solid participation in the various opportunities that arose during this phase to impact the discussions surrounding the NDP. This included engaging collective spaces, holding bilateral meetings with members of Congress, and providing technical assistance in reviewing amendments. Each of these opportunities presented several challenges.

Collective discussion spaces

As part of its advocacy strategy, TpC participated in two collective discussion spaces and organised an additional one to discuss the NDP’s articles. The TpC-led event was designed to facilitate a technical and proactive exchange between members of Congress from various political parties, their advisors, academics, and civil society representatives. The objective was to develop recommendations to mainstream anti-corruption measures, transparency, and accountability into the NDP. During this space, the conversation revolved around the absence of a cross-cutting anti-corruption approach in the NDP, the removal of anti-corruption measures in the proposed articles, and the opportunities for improving the text before the first debate began.

The advantage of organising such events is that the organiser has the freedom to define the timing, format, methodology, invitees, and topics of discussion. In contrast, participating in spaces organised by other CSOs can offer fewer opportunities for influence due to constraints set by the organiser, such as time limitations or specific topics for discussion.

Nevertheless, while collective spaces for dialogue represent a window of opportunity for CSO advocacy, they also present several challenges. First, the ability of CSOs to organise such spaces depends on the human, financial, material, and technical resources. These factors determine the size, scope, quality, and frequency of the events, and consequently play a crucial role in shaping the impact and effectiveness of CSO participation in legislative processes.

Second, the CSO must develop a methodology that optimises their contribution in these spaces. This requires prior mapping of pivotal actors, identifying their specific areas of interest, and determining the best approach to engage with each of them. A potential solution to these challenges is to create joint collective spaces and co-lead them with other CSOs. This would enable the pooling of capacities, resources, and expertise from multiple organisations.

Third, since participation in these spaces is voluntary and not convened by the sponsor of the bill, it can frequently be challenging to persuade strategic actors – such as members of Congress and government officials – to attend. To address this challenge, it has proven to be effective for CSOs to:

- Prioritise invitees based on their specific interests and roles in the legislative process being discussed, ensuring that all political parties are included

- Clearly highlight in the invitation how their participation will offer valuable insights into the legislative discussion

- Confirm attendees’ participation a few days before the event through various channels, to ensure effective engagement

Bilateral meetings with members of Congress

TpC’s participation in both their own and other CSOs’ collective discussion spaces opened a new avenue for advocacy: bilateral meetings with members of Congress. TpC was invited, prior to the bill’s first debate, to four meetings with advisors to the House of Representatives to discuss the progress, challenges, risks, and opportunities associated with mainstreaming anti-corruption in the NDP. These meetings enabled closer contact with congressional advisors, allowing for a more detailed discussion regarding public funds management and the creation of a National Anti-Corruption Strategy to address corruption from a systemic approach.

As one representative of a CSO who was interviewed noted, meetings with advisors are the most productive and effective in terms of advocacy, as they are the ‘most suitable mechanism for conveying ideas to congressmen, given their specialised technical knowledge in specific areas’.c4b0cc420d47 For TpC, these spaces were crucial for understanding in detail the concerns of legislators regarding the NDP and reinforcing the importance of adopting, through proposals for amendments, the observations made on anti-corruption measures.

Technical assistance in reviewing amendments

The set of advocacy strategies implemented so far has established TpC as a strategic technical partner for legislators, enhancing the discussion of the NDP in terms of anti-corruption measures. Consequently, during the discussion phase, TpC provided technical assistance to members of Congress in the review of amendments. This is relatively uncommon, as members of Congress do not always seek this type of support. When they do, they expect their concerns to be addressed with the same immediacy with which the discussion is conducted in Congress.

Post-legislative phase

The enactment of the NDP led some CSOs to pursue strategic litigation before high courts. To date, over 40 public actions of unconstitutionality against the NDP have been presented to the Constitutional Court by CSOs, requesting the repeal of articles deemed unconstitutional.16bad94657ba While none of these address issues related to corruption, they demonstrate the capacity of CSOs to impact the laws that have already been approved.

The results

TpC’s legislative advocacy activities focused on advancing recommendations in the following thematic areas:7cc1ba6b46f4

- Anti-corruption approach: Strengthening the country’s anti-corruption institutional architecture, and the creation and implementation of a NACS

- Implementation of the Peace Agreement: Applying the measures designed to guarantee the right to access information, ensure budgetary and contractual transparency, and establish accountability processes and territorial equity

- Environment: Enhancing entities’ capacities to prevent environmental crimes, improving the interoperability of systems which contain and manage environmental data and policies, and publishing that information in clear and simple formats for citizens

- Formalisation of public employment: Incorporating criteria of competence and merit in new modalities for accessing public employment

- Public–grassroots alliances: Establishing clear and objective criteria for the distribution, administration, and use of public resources; enhancing accountability; centralising information; maintaining open data formats; and ensuring citizen consultation

- Citizen participation in public decision-making and management: Creating spaces for citizens to actively participate in public decision-making processes

- Social protection system with universal coverage: Given that government transfers are intended to support communities and citizens living in poverty and vulnerable conditions, it is key to publish – in real-time and in open data format – the resource allocation algorithms and criteria, the status of resource execution, and the list of the final beneficiaries of those transfers.

- National drug policy: Incorporating measures to prevent acts of corruption by criminal groups associated with drug trafficking, and strengthening actions to monitor illicit financial flows and money laundering

- Administration of funds: Including the obligation to publish contractual information and accountability mechanisms targeting companies or entities that manage public resources

- Budget transparency: Creating a public access website for budget-related information and ensuring the interoperability of data in the existing information systems

- Extraordinary powers of the president: Precisely defining the scope of the extraordinary powers granted to the president by the NDP and establishing a periodic obligation to render accounts

- Dissolution of CSOs: Adjusting provisions in accordance with the international standards established by the Organization of American States (OAS) on the right to freedom of association

TpC’s anti-corruption advocacy on the NDP yielded mixed results during the legislative process. Not all of the proposed recommendations were included in the final draft of the NDP. For example, certain recommendations adopted during the first debate were later removed in the second debate’s report. Likewise, other recommendations that made it into the second debate were eliminated during the final conciliation of articles (see Annex 1).

Nonetheless, TpC had important wins. During the discussion of the bill, legislators removed most of the articles that granted ambiguous extraordinary powers to the President and modified the text to ensure that public procurement rules applied to public funds. TpC proposed these adjustments due to concerns about corruption risks associated with discretionary decision-making and lack of transparency in information, which legislators accepted. Moreover, through its legislative advocacy, TpC succeeded at convincing the government to establish the NACS.

The proposal to establish a NACS stemmed from TpC’s earlier work, which had identified the need for a comprehensive and sector-specific approach to address corruption. The House of Representatives’ interim Commission on Anti-Corruption and Public Integrity adopted the proposal and championed TpC’s recommendation before the full chamber. After drafting the NACS amendment, the authors sought TpC’s expert input to strengthen it with an anti-corruption focus.

For the NACS amendment to be included in the NDP, it had to be supported not only by the majority of the senators and representatives but also by the National Planning Department. Nonetheless, the National Planning Department was reluctant to incorporate it into the final text of the NDP, since ‘they did not want to assign new functions to entities’.b222a8946a6d

In this context, TpC recognised the need to develop a communication strategy to make this proposal visible and apply pressure to both members of Congress and officials from the National Planning Department to approve the amendment related to the NACS. To this end, TpC published a press release across several media outlets1dd3f4202ec4 and wrote a thread on X3d599780b887 to expand its reach on social networks. These efforts gained traction, with the media outlets covering the need for a NACS in Colombia and citizens engaging by sharing and commenting on the X thread. As a result, members of Congress endorsed the NACS, leading to its incorporation into the final text of the NDP bill on 19 May 2023.

The implementation of the NACS has been slow. It was not until May 2024, that the national government published a draft decree regulating the NACS. To date, this proposal is still being refined, with no concrete steps taken towards implementation. Moreover, the draft decree still lacks coverage on critical issues, such as guaranteeing human rights, protecting public resources, ensuring conditions for socio-economic development, and safeguarding the environment.

In response, TpC promptly sent observations and technical recommendationsc27542c20642 through official channels to the National Planning Department. TpC advocated for the NACS to: include a differentiated approach for territorial entities; align with existing national legislation; broaden the definition of corruption to recognise victims of corruption and focus on reparations; and produce reports to monitor and warn about potential corruption acts.

The final decree has not yet been published, so it is too early to determine if TpC’s recommendations have been considered. In any case, what happened with the NACS illustrates that sometimes the inclusion of anti-corruption measures in a law is insufficient to advance counter corruption. Effective regulatory and implementation processes are also essential.

Lessons learned

TpC’s efforts to mainstream anti-corruption in the NDP helped to identify several lessons for future anti-corruption legislative advocacy:

- Advocacy opportunities, such as bilateral meetings and technical assistance, can pose risks for CSOs. They may be instrumentalised by members of Congress and public officials to advance their own agendas, stigmatised for supporting a particular senator or representative, or misinterpreted as lobbying.

- CSOs should evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of each advocacy opportunity before engaging.

- The effectiveness of advocacy efforts often depends on the CSOs’ ability to adapt to congressional dynamics and timing.

- Technical assistance to members of Congress and public officials – leveraging CSOs’ expertise – is the window of opportunity that has the greatest potential for direct impact, as it facilitates more direct dialogue.

- In collective discussion spaces organised by other CSOs, advocacy opportunities may be fewer as they are limited to the parameters set by the organisers. To be more impactful in these spaces, ‘it is useful to prioritise primary messages and clearly show how they contribute to the bill’s discussion’.c1e7e6ff8bd0

The National Health Reform

Between February 2023 and April 2024, TpC conducted legislative advocacy to integrate anti-corruption measures into the bill that sought to restructure Colombia’s health system. As part of its ALA initiative, TpC leveraged various advocacy opportunities. These included: participation in closed-door technical roundtables; raising awareness about corruption risks on social media; participating in collective discussion spaces; and partnering with health sector CSOs and experts to broaden its impact.

Since TpC lacked experience in the health sector, its legislative advocacy strategy involved establishing continuous dialogue and collaboration with health experts to integrate its anti-corruption approach with sector-specific expertise. This innovative approach allowed TpC to establish itself as a relevant actor in the Health Reform discussions, becoming the only actor not directly associated with the health sector to be included in these discussions.

In this case, Así Vamos en Salud – a CSO with expertise in health – was strategic in integrating the anti-corruption analysis into the reform bill. This hand-in-hand work was possible because their team identified possible corruption risks in the bill and, in researching possible allies, identified common agendas with TpC and then connected with them with the idea of conducting a joint analysis.

Although not all of TpC’s recommendations were incorporated into the bill, its advocacy efforts successfully positioned the need for anti-corruption measures to comprehensively address corruption in the health sector. Additionally, when the Reform bill reached its third debate (out of four), the corruption and implementation risks identified by TpC were crucial in the decision of the Senate’s Seventh Commission to reject the bill.

Several lessons were learned from this experience, including the importance of collaborating with sector-specific CSOs to access new stakeholders and advocacy spaces, as well as the need to incorporate an anti-corruption approach in discussions of sector-based bills for protecting human rights.

This section provides an overview of Colombia’s current health system, followed by a brief analysis of the bill presented by the national government. It also outlines the opportunities, obstacles, and challenges identified when conducting anti-corruption legislative advocacy for sector-based bills, as well as the results.

Colombia’s health system

The Colombian General System of Social Security in Health aims to ‘guarantee the fundamental right to health, regulate it, and establish protection mechanisms’.7b877358169a To ensure universal health coverage, four essential functions were established: resource financing, resource administration, regulation, and health service provision.7bdd4d0472e6 In each of these, both private and public sectors are involved.

Resource financing

The health system is funded through two main regimes: contributory and subsidised. The contributory regime covers employed individuals, including the self-employed, while the subsidised regime supports those without employment who cannot contribute. It is the state’s responsibility to ensure access to health for those who cannot afford it. In 2023, the health sector received 59 billion Colombian pesos (approximately US$14,000,000), representing 18% of the national budget,229be0a4c21b making it the second-largest recipient of budgetary resources.

Resource administration

Health Promotion Entities (HPEs) administrate the system by offering insurance to people and managing financial risks in the provision of health services. They handle resource administration and contract Healthcare Service Provider Institutions (HSPIs) to offer services nationwide. According to data from the Ministry of Health of Colombia, by May 2024, 27 HPEs were operating in the country.b86662473677

Individuals under the contributory regime choose an HPE, which provides them with a list of HSPIs they can use, as well as the medical and health services they can access.4e68724ccfb7 The HSPIs provide the HPEs with information about the services they have delivered to individuals connected to the HPEs that they are contracted with.1542efd3fff3 The HPEs verify this information and request the Administrator of the Resources of the General System of Social Security in Health (ARGSH) to distribute funds to pay the HSPIs.3ba369aa2ad4

Regulation

The regulatory process is overseen by two public institutions: the ARGSH and the Superintendence of Health.dc91faef7b04 The ARGSH verifies the accuracy of information submitted by the HPEs, while the Superintendence of Health ensures that the HPEs meet financial requirements for their operation and service quality standards.5c9aac5a45bb

Health service provision

The HSPIs, which are private sector clinics, and state social enterprises (SSEs), which are public sector hospitals, are responsible for providing health to users referred by the HPEs with which they have agreements.

The implementation of this system has dramatically increased universal health coverage, from 22% in 1995 to 98.55% in May 2024.f4ed5fe93fa6 It has also led to substantial improvement in main health indicators. Between 1993 and 2022, the adolescent fertility rate dropped from 84.68% to 56.81%; the infant mortality rate decreased from 24.9% to 10.65%; and the life expectancy at birth increased from 69 to 73.7 years.7388ed849617

Nevertheless, the system still faces challenges related to access to and the quality of health services at the territorial level, social determinants affecting health quality, and the timely care for high-cost diseases. Between 2016 and 2020, 67 acts of corruption directly related to the health sector were reported in the press. These events were mainly administrative (63%), private (27%), and political (10%). The estimated cost of corruption in these cases was US$1.63 trillion.1508006ea330

What did the Health Reform aim for and who was involved?

In February 2023, the Ministry of Health submitted a bill to reform the health system.09a3aa29bf95 The Health Reform aimed to shift from a predominantly curative model to one focused on primary care, emphasising prevention, prediction, and resolution. The proposed measures, according to the text filed, were:

- Enhancing transparency in resource management

- Strengthening oversight, inspection, and control of the health system

- Addressing gaps in service delivery and access to medicines, and improving responsiveness to the needs of each territory

- Settling debts of HPEs with HSPIs that have public or private – or mixed – ownership

- Improving coordination between public and private stakeholders

- Centralising the administration of the system’s financial resources in the ARGSH and, consequently, eliminating the HPEs as intermediaries between the ARGSH and the HSPIs

- Strengthening citizen participation in the decisions

- Formalising health personnel by providing permanent contracts and improving their working conditions

The proposed structural changes to the system sparked divided opinions among stakeholders. Those in favour argued that these adjustments would address the system’s existing shortcomings.dfa31a7a7797 In contrast, critics – including HPEs, HSPIs, health professionals, suppliers, and grassroots CSOs – raised concerns that the proposed changes would negatively impact access to and the quality of health services, thereby compromising the right to health.585540be1fde

Additionally, the Health Reform lacked a comprehensive strategy to address corruption within the sector.e03e5f5e1289 Also some of the proposed measures could have inadvertently created or exacerbated corruption risks.

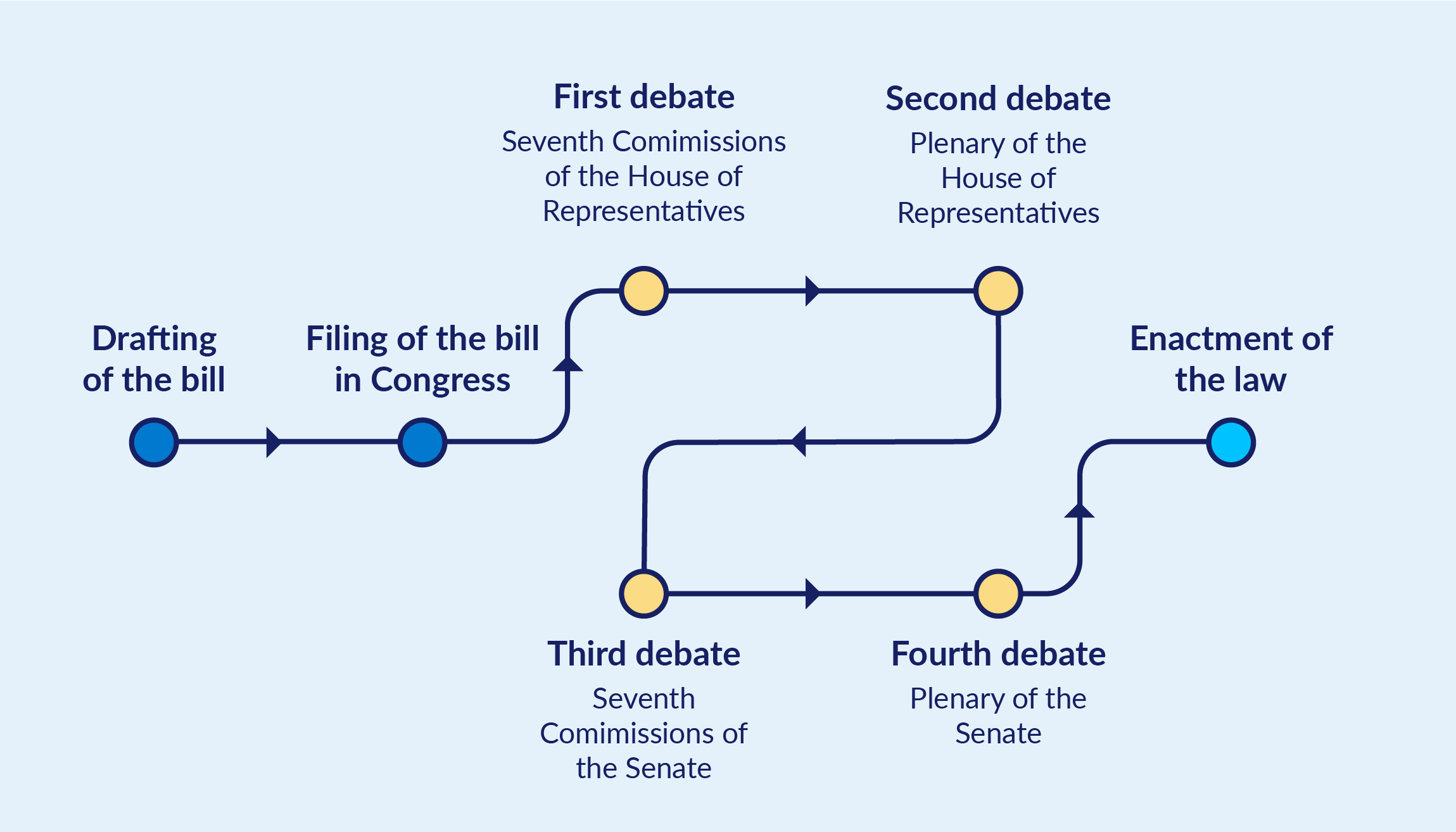

To become law, the Health Reform’s bill needed to be approved in four debates: two in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate of the Republic. The bill had to pass the first debate by 20 June 2023, and be approved in the remaining three debates by 20 June 2024.7957c3722419 This timeline provided legislators with sufficient time to analyse and consult on the aspects that generated doubt (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Legislative process of the Health Reform

In addition to the Ministry of Health as the bill’s author, several other public entities participated in the legislative process, including the ARGSH, the Superintendence of Health, the National Institute of Drug and Food Surveillance, and the Ministries of Education and the Interior.

TpC identified two reasons for engaging in anti-corruption legislative advocacy in this bill. First, some of the proposed measures were likely to create risks of corruption and implementation challenges, which could undermine the system’s effectiveness and impact the guarantee of Colombian’s right to health. Second, the bill represented an opportunity to address and mitigate corruption within the health sector, thereby improving the availability, timeliness, and quality of health service provision.72c195a441b8

TpC’s strategy

As with the NDP, TpC conducted advocacy activities across all three phases of the legislative process.

Preparatory phase

For the bill-drafting process, the Ministry of Health decided to prioritise patient associations as representatives of citizens. This decision took into account the challenges faced by the National Planning Department in incorporating citizen input through the Binding Regional Dialogues in the preparation of the NDP. Despite the government’s intention to incorporate citizens’ contributions into the NDP, the sheer volume of suggestions and the impossibility of incorporating them all into the reform meant that citizens’ expectations were not met.

Considering this, the Ministry of Health convened various working sessions with patient associations in closed-door meetings between January and February 2023. This was the first opportunity civil society had to engage in the legislative process of the Health Reform. According to a representative from a patient-focused CSO who was interviewed, ‘these meetings provided a platform to voice concerns about the health system’.7a395d043c8c

Many of their observations and recommendations were successfully included in the bill presented to Congress by the Ministry of Health. As noted by an attendee of these meetings, the effectiveness of their advocacy efforts was attributed to ‘the multiple sessions held, which allowed a comprehensive explanation of the proposals, and to the Ministry of Health’s demonstrated interest and willingness to integrate the suggestions provided’.6af7d0e0dd51 The consolidated relationship with the Ministry of Health during the preparatory phase was crucial for patient associations’ advocacy efforts. During the discussion phase, the Ministry acted as a bridge between these associations and Congress, enabling them to successfully incorporate their recommendations into the bill during the discussions in Congress.

Prioritising the participation of grassroots CSOs – such as patient associations – in the bill-drafting process was crucial, as they represent people with a common interests. These organisations possess in-depth knowledge of the health system’s functioning and unmet needs of patients.7cf98fb99cd0 However, other types of academic or technical CSOs were not given the opportunity to participate in the bill-drafting process of the Health Reform. For TpC, this represented a significant barrier to advocating for the incorporation of an anti-corruption approach, both to address corruption in the current system and to mitigate potential corruption risk that could arise from the implementation of the proposed measures.

Discussion phase

The submission of the Health Reform bill brought new opportunities for CSOs interested in conducting legislative advocacy. In March 2023, the Seventh Commission of the House of Representatives convened nine public hearings in different cities across the country to gather the main citizen concerns regarding the health system.1187304a8acb However, according to interviews with experts in the sector – and similar to what occurred with the NDP – citizens did not perceive their contributions were reflected in the report for the first debate.

In addition, during the period between the drafting of the bill and the consolidation of the report, neither the Ministry nor the members of Congress invited anti-corruption CSOs to contribute to the text of the bill. This can be partly explained by the fact that anti-corruption CSOs did not necessarily have technical knowledge of the health sector and, as a result, they were not prioritised in the discussion.

However, in February 2023, when the first debate on the Health Reform was scheduled, TpC collaborated with a health-related CSO, Así Vamos en Salud (AVS, for its initials in Spanish) to carry out a broader analysis of the health sector and identified the following corruption risks in the reform:

- There are potential administrative and transparency risks associated with the contracting processes of health services.

- There is a lack of clarity regarding the financing and the establishment of new bodies responsible for coordination of the services across the country – services which traditionally have not worked well together. Moreover, the proposed reform did not outline clear accountability mechanisms to mitigate corruption risks in decision-making processes.

- The reform does not provide assurances regarding the availability of budgetary resources to finance training programmes, or the relocation of professionals currently employed by the HPSI.

- The proposed reform did not allocate budgetary resources to train public servants who would take leadership roles under the HPSI. Neither did it provide specific criteria for the recruitment and selection of this personnel. In this context, conflicts of interest could likely turn into corruption. This was a special concern for regional hospitals, as many are captured by corrupt networks or by particular political interests, and it is seen that these interests influence the procurement of medicines, services, and technologies.

- It is imperative to establish a dedicated entity to oversee the training of officials tasked with reporting data to the health system. This would facilitate citizen- control exercises and decision-making for adjustments in the sector.

- The extent to which the ARGSH would be able to assume the responsibilities of the HCPs – that is, collecting and managing users’ data submitted by the PSIs, and paying the PSIs for their services provided – should be considered. This would be in addition to their ongoing role of auditing the quality of information submitted. This situation could enable corruption, given that a single actor is responsible for carrying out the entire process without the capabilities and without an external auditing process.

- There is potential for opacity and corruption in the audit and payment process for the provision of health services. The reform proposes a payment scheme of 80% upon presentation of invoices and 20% following the audit, which carries significant risk for the stability and financing of the system, given that a substantial portion of public resources is committed without a prior review process.

Based on this analysis, TpC and AVS focused on three fundamental aspects to promote anti-corruption measures:f688f75d4bc7

- Visibility of and access to information:Corruption risks were identified due to opacity in information, restrictions on access to public information, and a lack of adequate tools to guarantee the supervision of the management of the public resources.2a97c82b8b85

- Institutional framework and governance:The proposed governance of the health system was complex and did not subscribe to a thorough and clear auditing process. This could increase discretion in the decision-making processes and in the management of the health system – magnifiying the risk of corruption.

- Control and sanction: Corruption risks arose from a weak culture of self-regulation, inadequate external control, weak mechanisms for sanctioning corruption, and a lack of guarantees for citizen participation and oversight.

TpC recommended:

- Implementing a comprehensive budget transparency strategy that covers all funding sources for the health system, allowing real-time tracking of public resource usage by all involved actors (public, private, national, and local)

- Ensuring mandatory publication of procurement information by individual institutions – both public and private entities

- Creating effective interoperabilityschemes for existing information systems

- Establishing clear, objective criteria for centralised medication purchases throughpublic auctions, to mitigate discretion in decision-making

- Developing sectoral anti-corruption strategy that integrates various system actors, builds on existing mechanisms, and addresses sector-specific risks such as power co-optation in regional public hospitals and health departments

- Adjusting the length of term of the directors of the HSPIs to ensure it does not overlap with the term of the municipal or district mayor or governor; this change aims to prevent political interference in the appointment of HSPI directors and reduce the risk of clientelism at the local level

- Strengthening institutional capacity of the ARGSH and mechanisms for prior, concurrent, and subsequent auditsto prevent mismanagement of health resources and ensure a proper and transparent flow of funds throughout the system

- Establishing a merit-based selection processfor the Superintendent of Health

- Creating specific mechanismsfor citizens and institutions to report corruption, and to protect whistleblowers

- Incorporating mechanisms to ensure transparency and controlover logistics operators distributing supplies, medicines, and goods nationwide, ensuring price variations between regions are based on objective criteria

Prior to the scheduling of the second debate, the interim Anti-Corruption Commission of the House of Representativescb00a3048fbd convened a technical roundtable on 25 April 2023to discuss the corruption risks related to the Health Reform.3c94e440c8c5 This space resulted from the advocacy efforts of CSOs that were part of the commission’s Technical Secretariata64cf7b30d8a as well as health sector experts, who used the media to highlight certain corruption risks associated with the implementation of the proposed Health Reform. Nevertheless, the roundtable included only health sector experts and only two anti-corruption experts: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre and TpC. The ongoing collaboration with AVS allowed TpC to introduce an anti-corruption analysis into the Health Reform discussion, demonstrating a deep understanding of the health sector.

In October 2023, the House of Representatives established an interim Commission for Health Reform, which organised six national dialogue roundtables to reach agreements and draft the report to be discussed in the second debate.672e081f085a These roundtables prioritised the engagement of health sector actors, patient associations, HPEs, health sector trade unions, and selected academics, limiting once more the involvement of anti-corruption CSOs.

Despite this, TpC was able to indirectly participate in these spaces through AVS, which was invited for being a health-related CSO. This collaboration allowed TpC to provide a more thorough analysis of the 143 articles in the Health Reform and offer more specific recommendations.51c647c7c0ae This helped members of Congress to identify inherent corruption risks in the Health Reform and provided a more comprehensive understanding of how corruption manifests in the health sector.

When the bill moved to the Senate for its third debate in December 2023, new advocacy opportunities arose. The Seventh Commission of the Senate bureau convened 14 public hearings across various cities of the country to collect inputs from different sectors.d81922294525 Approximately 2,000 people attended these hearings. However, the focus on informing the public about the Health Reform was prioritised over ensuring meaningful citizen participation. One interviewee described these participatory spaces ‘a fallacious democracy’, noting that ‘citizens were heard, yet their observations and proposals were not incorporated into the bill’.e955bee3dd79

In February 2024, before the third debate, the Seventh Commission of the Senate convened seven closed-door technical roundtablesto facilitate a dialogue between experts and public entities from the health sector and obtain their perspectives on the Health Reform.d96938f9aebf This invitation came just ten days after TpC requested a public hearing in Bogotá through formal communication channels.

Unfortunately, none of these roundtables addressed anti-corruption issues. The prioritised topics were related to the licensing, production, and distribution of medicine; working conditions of health professionals; patient experiences in the Colombian health system; governance and use of information technologies; experiences and perspectives on primary healthcare; extramural teams and health service networks; and financial aspects of the health system, including resource flow, payments, and sustainability. Nevertheless, TpC participated in the governance and use of information technologies and in the financial roundtables, where recommendations were shared on budget and procurement transparency, the audit system, and the need to develop a sectoral anti-corruption strategy. The participants’ interventions resulted in 147 conclusions, which included TPC’s concerns about corruption vulnerabilities within the Health Reform, and these became the basis for the Senate’s decision to reject the Health Reform.

From the submission of the bill to its rejection, TpC, AVS, and other CSOs held bilateral meetings with members of Congress,which were crucial opportunities for discussing the positive and negative implications of the Health Reform proposals. This facilitated a more technical and detailed discussion of the Health Reform.

Throughout the discussion phase, TpC used media to broaden the scope of its advocacy efforts. TpC conducted a communication strategy to disseminate the identified corruption risks and its recommendations to address them. This included creating reels and stories on Instagram, and threads on X, as well as contributing to press columns, radio interviews, and analysis in television programmes.

One significant challenge was gaining coverage from mainstream media, as initially journalists did not perceive the anti-corruption perspective as compelling. To overcome this, TpC developed a joint communications campaign with AVS, successfully reaching journalists interested in both anti-corruption issues and health issues. These efforts also contributed to strengthening public opinion regarding the bill.

Post-legislative phase

Ultimately, the bill was rejected in April 2024 due to concerns that its provisions were impractical, failed to address the underlying structural issues of the health system, and jeopardised the financial sustainability of the health system.912e7f3c3832

On 8 May 2024, senators from the Seventh Commission who opposed the Health Reform organised a consultation forum to collectively develop a technical and feasible approach aimed at strengthening the Colombian health system, improving the service’s coverage and quality, and ensuring long-term sustainability.06ab2f0d025c The attendees included: grassroots CSOs (eg patient organisations for those with orphan diseases); academic CSOs (eg university research centres); health sector expert CSOs (eg AVS); and corporatised CSOs (eg the Colombian Association of Integral Medicine Companies).

TpC was once again the only anti-corruption CSO invited to participate in the discussion. This reflects the growing recognition among some legislators of the need to incorporate an anti-corruption approach into the Health Reform discussion. It also demonstrates that integration of TpC’s anti-corruption approach with sector-specific experts – as was the case with AVS in this instance – is crucial for mainstreaming anti-corruption measures in the sectoral discussions.

The results

The advocacy efforts of TpC and AVS had mixed results. While several of their recommendations were included in the report presented for the second debate, during the debate itself, the text was altered to the point of contradicting many of the original recommendations. For example, the article establishing a merit-based process for appointing directors of state social enterprises (article 42) was revoked, perpetuating political patronage risks at the territorial level. Additionally, the percentage of invoices paid without prior audit was increased from 80% to 85% (article 70), generating risks associated with the misuse of public resources.99fd1a87a9f7

Moreover, there was not enough political will to address core concerns, such as committing to transparency measures during the transition period from the existing model to the new one, reconsidering the procedure for calculating the Capitation Payment Unit,516dc7f01481 and defining and limiting the new proposed functions for the ARGSH.0c455f57bca0

However, there were some positive outcomes in the second debate, as several other anti-corruption recommendations issued by TpC and AVS were incorporated into the text (see Table 3).

Table 3: Recommendations adopted by the Plenary of the House of Representatives

|

Recommendation issued |

Adjustment made |

|

The Health Reform assigns to the ADRES/ARGSH the functions of collection, management, payment, and audit of resources and expenditure. This excessive concentration of functions within the ARGSH creates significant corruption risks. |

Accountability measures for the ARGSH’s corporate governance were included, enhancing oversight and transparency while limiting the discretion in decision-making. |

|

Although extraordinary powers of the president are established in the Constitution and the Law, the Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence indicates that they must be clearly defined to mitigate risks associated with the concentration of power and discretion in decision-making. |

The extraordinary powers of the president to issue provisions for capitalising a public HPE named ‘the new HPE’ were eliminated. |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration

In general, the impact of the recommendations was limited, partly because many legislators were not fully aware of the need to incorporate anti-corruption measures into the Health Reform. Nonetheless, TpC kept highlighting potential corruption and implementation challenges within the Health Reform, while advocating for the inclusion of anti-corruption measures to address these issues.

Consequently, during the second debate, several members of the House of Representatives recognised that all proposed adjustments must include anti-corruption measures to safeguard public resources and ensure the functioning of the health system. As a result, TpC was invited to consultative spaces throughout the post-legislative phase during April, May, and June 2024.

Despite the limited impact of the anti-corruption legislative advocacy that was conducted, this experience opened up opportunities for TpC to collaborate with other organisations and raise awareness about corruption in the health sector.

On 13 September 2024, the Ministry of Health presented a new bill on the Health Reform.ddf7b7bdb8d9 Therefore, TpC continues to prioritise anti-corruption advocacy in the health sector.

Lessons learned

TpC’s efforts to integrate anti-corruption measures in the Health Reform identified several main lessons for future legislative advocacy on this issue:

- Partnering with sector-specific CSOs and health sector experts creates new advocacy spaces and allows for the quick drafting of precise observations on and well-founded recommendations for a bill, leveraging the strengths and expertise of both CSOs.

- Incorporating an anti-corruption lens into sector-based bills is essential for protecting human rights. Sectoral actors recognise corruption but often lack solutions. Therefore, advocating for anti-corruption measures within sector-specific legislation is critical to promoting a systemic approach to countering corruption.

- Effective advocacy within sector-based bills requires clear and concrete recommendations that translate technical concepts into actionable solutions, presented in attractive formats and using simple language, quantitative data, and compelling messages. Providing real-life examples to highlight the impact of corruption within the sector can make the message resonate.

Eight windows of opportunity for legislative advocacy

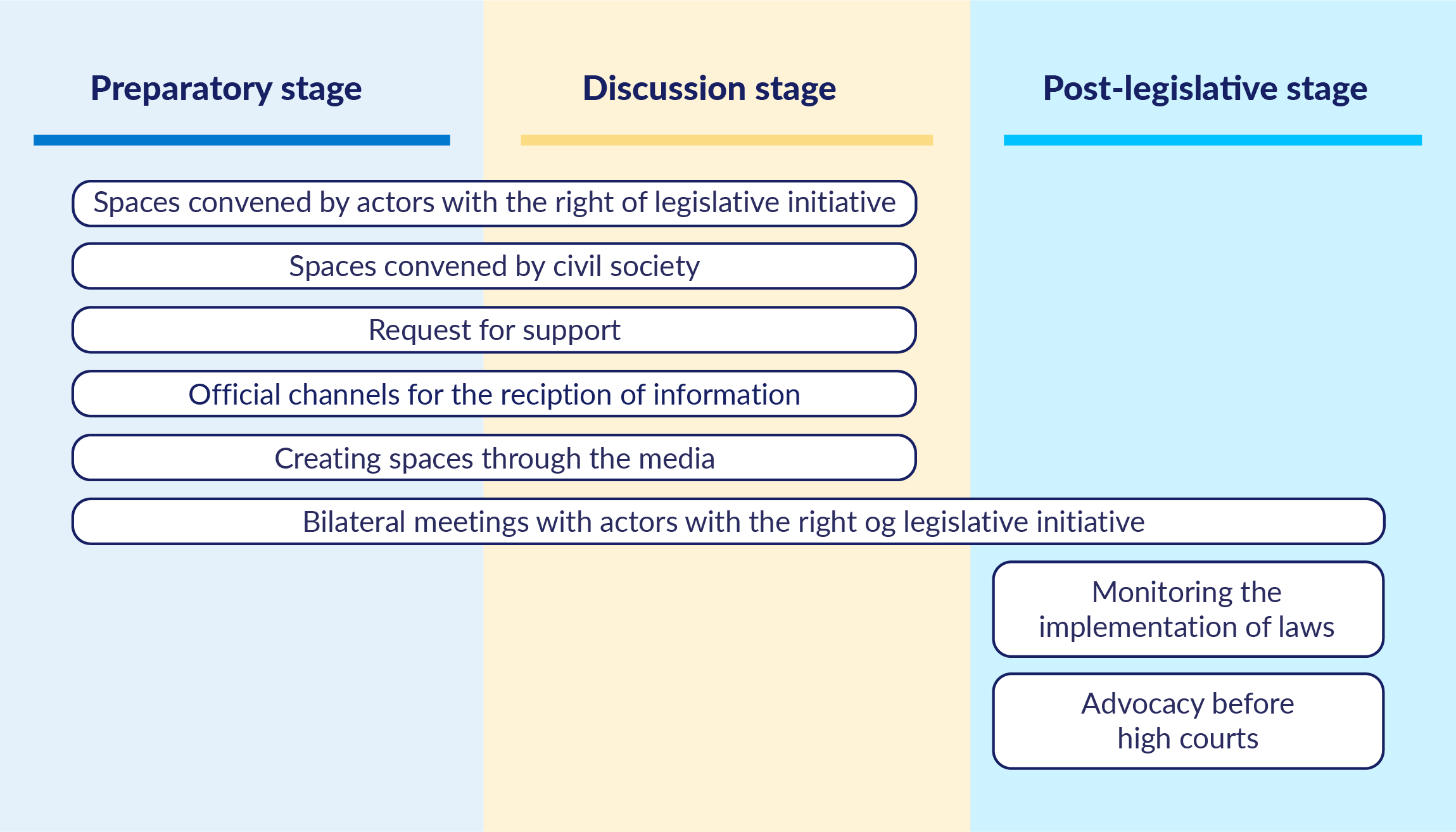

TpC’s experience in these two case studies has identified eight windows of opportunity for CSOs to engage in anti-corruption legislative advocacy (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Windows of opportunity to influence the legislature by phase of the procedure

These windows are typically brief and depend on several factors, such as the nature of the legislation, the prevailing circumstances, and the existing political will. It is also worth noting that choosing one window of opportunity does not mean that others cannot be taken advantage of simultaneously or afterward. In fact, in the cases studied, several windows were utilised during the legislative process.

However, experience and research reveal that it is not always strategic to engage in every opportunity that arises – as the effort can be significant, and the results are not always proportional. For example, in the case of the NDP, a considerable investment of resources (human, financial, material, and technical) was made to position TpC’s recommendations, but in the end, the most strategic and effective approach was to focus on the NACS.

It is also important to acknowledge that legislative advocacy presents various challenges.

Incorporating CSOs’ observations and recommendations into bills

Despite developing strategies and tools to impact legislation, CSOs’ contributions are rarely reflected in bills. The research reveals there are two main reasons for this. First, members of Congress often do not see the added value of CSOs’ observations and recommendations. This leads to insufficient support for their incorporation. Second, CSOs are frequently invited to participation spaces that do not foster genuine dialogue; neither does their participation result in their input being incorporated into the bills.

The nine-member focus group revealed that to increase the incorporation of their recommendations, CSOs continuously review and adapt their advocacy strategies, considering the timing, legislative dynamics, issues of public relevance, and opportunities for collaboration with other CSOs. Nevertheless, as CSOs do not have the authority to directly modify bills, they must always rely on legislators as intermediaries to bring about changes. This will always be a limitation to the effectiveness of CSO advocacy.

Ultimately, it is important to acknowledge that the success of legislative advocacy efforts should not be measured solely by the changes made to bills. Advocacy can also be considered effective when, for example, the actions undertaken lead to the rejection of a bill due to its potential to create new corruption risks or exacerbate existing ones, as occurred with the Health Reform. Additionally, even if a bill is not modified, advocacy spaces such as bilateral meetings with members of Congress can contribute to shifting their perspectives and influencing their work in the long term.

Aligning legislative agendas

Congress members, public entities, and CSOs define their legislative agendas based on particular interests. Consequently, the topics prioritised by CSOs often do not align with those promoted by legislators, ministries, or other government officials promoting legislation.

This discrepancy is particularly evident in anti-corruption efforts. Despite corruption being a prominent political banner of most parties during elections, the anti-corruption agenda is frequently deprioritised by most legislators once elected.

To overcome this challenge, some CSOs have to identify the common ground between both agendas and focus their legislative advocacy efforts on them. For instance, during the discussions on the NDP, TpC successfully integrated anti-corruption measures into articles on environmental issues, budget transparency, and fund management. This was achieved by engaging members of Congress on topics they cared about and demonstrating how anti-corruption measures could contribute to advancing their agenda.

In cases where none of the topics on both actors’ agendas align, many CSOs opt out of legislative advocacy. However, others develop innovative strategies to engage with members of Congress and relevant public entities to ensure their topics of interest are recognised, valued, and prioritised. To achieve this, it is essential to clearly communicate how CSOs’ input can strengthen the bills that are prioritised by legislators and public entities who are authorised to submit them to Congress. As one CSO member who was interviewed stated, the objective is to ‘market ideas’ that resonate with congressional interests.

While this approach is complex, it has been a fundamental strategy for TpC, as an anti-corruption CSO, for introducing this new topic into certain legislators’ agendas. For example, at the outset of the Health Reform bill, most members of Congress did not prioritise the potential corruption risks inherent to the Health Reform proposal. It was only through TpC’s targeted alerts that the anti-corruption approach gained attention. TpC highlighted how corruption threatened the state’s ability to ensure the right to health – an issue that aligned with congressmen’s interests. This approach led some legislators to advance TpC’s arguments and recommendations in their discourse during the debates.26c26cf1b9ac

Coordinating dialogue spaces

Coordinating dialogue spaces between CSOs, members of Congress, and government officials presents significant challenges. Sometimes they lack interest in engaging with civil society; while in other cases, they have constrained schedules. However, CSOs have developed some practical strategies to address this challenge.

In some instances, it has been useful to propose brief, focused conversations at times and formats convenient for legislators and government officials. Alternatively, engaging with their advisors – who often have more time and willingness to delve into the proposed issues – has proven to be easier and more effective for advocacy purposes. This approach was successful during the NDP discussions.

Another strategy has been to identify legislators and government officials with a strong interest in a bill under discussion and whose statements align with the CSOs’ proposed recommendations, and to focus advocacy efforts on them. Once the target actors are defined, CSOs should clearly define the objectives of their legislative advocacy, but also the added value of their inputs in the drafting and discussion of the bill. Ideally, these contributions should be supported by solid technical evidence.

Building capacities for effective legislative advocacy

One of the principal findings of the research is that to increase the chances of success, it is crucial for CSOs to build their capacities to engage effectively in the legislative process. The interviews highlighted a direct correlation between CSOs’ capacities and the success of their impact on legislation. One of the public officials who was interviewed noted, ‘organised civil society is currently the only entity with the capacity to participate and have an impact. However, in Colombia, civil society’s influence in legislative matters has often been monopolised by corporate organisations, meaning that only certain interests are represented in Congress.’628ea210a8c3

Initially, one might assume that possessing basic knowledge of the legislative process or connections with members of Congress or their advisors is enough to influence legislation. However, the research indicates that, in most cases, this is insufficient.

Legislative advocacy requires human, financial, material, and technical resources to seize the windows of opportunity that may arise during the legislative process of a bill. Such resources are not always available and are difficult to access. In both case studies, these resources were essential for organising collective discussion spaces, attending bilateral meetings, and closely monitoring the bill’s debates. For TpC, it was of significant benefit to have a team with the following qualities:

- A comprehensive understanding of the legislative process and the strategic thematic areas for both bills, eg anti-corruption, participation, health, human rights, peacebuilding, and environment, etc.

- Experience in bill-monitoring processes.

- Tools and methodologies to monitor members of Congress, public officials and, other relevant actors involved in bill discussions, to identify their interests, positions on issues, and relationships with others. Based on this analysis, appropriate anti-corruption legislative advocacy strategies can be developed.

Although only corporatised CSOs engage in lobbying to promote particular interests, legislative advocacy is often mistakenly conflated with lobbying. This misconception has become an obstacle for securing funding for legislative advocacy activities, as these initiatives are often perceived as conflicting with the guidelines of international cooperation. It is essential to clearly define the scope of these actions to avoid confusion and ensure alignment funding regulations related to lobbying.

Collaborating with other CSOs

Collaboration with other CSOs is an effective strategy for impacting legislation, as it enables the optimal use of resources by leveraging each CSO’s expertise and capacities. However, joint work between CSOs is not common practice. Competition often arises among CSOs, as each organisation seeks recognition for its advocacy efforts, which limits opportunities for joint action. Furthermore, even when mutual interests exist, reaching a consensus can be challenging.

For TpC, collaborating with other CSOs has been crucial for maximising its advocacy efforts. This approach has allowed TpC to reach a broader audience, apply pressure from various fronts, and gain access to advocacy spaces that were previously not available. This collaboration was particularly evident in TpC’s advocacy around the Health Reform. Several bilateral meetings were held with AVS, where common ground was identified, and joint efforts were made to impact the Health Reform discussions.

In conclusion, legislative advocacy requires continuous identification of available windows of opportunity and associated barriers to develop innovative strategies and tools that best suit the achievement of desired advocacy goals (see Annex 2).

Strengthening anti-corruption legislative advocacy

The recommendations below are directed towards three distinct groups: anti-corruption CSOs currently engaged in anti-corruption legislative advocacy or are considering doing so; members of Congress and government officials interested in identifying and creating spaces for CSOs participation in the legislative process; and the donor community.

Civil society organisations

Establish institutional processes for legislative advocacy

Clear institutional policies and procedures help CSOs maintain their reputation. TpC recommends:

Publishing advocacy activities and interactions with decision makers

Anti-corruption CSOs should proactively take transparency measures and share the following on their websites and social media: the members of Congress and public officials they interact with and whom provide technical assistance; the objectives of each advocacy activity; and the technical contributions made to legislative discussion. Sharing this information demonstrates the CSOs’ commitment to transparency and may encourage citizens to engage in legislative monitoring.

Defining ‘red lines’ for advocacy

To maintain the CSOs’ autonomy and optimise advocacy efforts, it is essential to define thematic and individual limits. This will provide clear guidance to CSOs on when they should distance themselves from an issue or actor.

Regarding thematic limits, CSOs must define concepts and premises that cannot be reconciled. This will allow them to establish conversations and advocacy actions with legislators, government officials, and other CSOs from a common base, which they can then build on. For instance, when discussing the Health Reform, TpC defined the following ‘red lines’ – issues upon which they were not prepared to compromise: health is a fundamental right; inequities in access to health services must be reduced; corruption undermines human rights; and corruption disproportionally affects vulnerable populations.

With regard to the individual limits, anti-corruption CSOs should avoid bilateral meetings with legislators or public officials who are under investigation or sanctioned for corruption, as well as those who pose risks to democratic institutions.

Creating social media content to strengthen citizen dialogue

Enhanced dialogue with citizens helps CSOs identify their needs and determine corruption risks associated with proposed bills. It is also important for CSOs to develop additional strategies to connect citizens with legislative activity. Informed citizenship can be crucial in expanding the reach of the concerns – and recommendations – of CSOs regarding a bill.

Develop actionable legislative advocacy strategies

When conducting legislative advocacy, anti-corruption CSOs can diversify the topics and areas they address. However, their advocacy efforts must be aligned with their capacities to ensure impact. TpC recommends:

Identifying legislative agendas

Once they have identified the legislative agendas of legislators, the government, relevant public entities, and other CSOs, anti-corruption CSOs should focus their advocacy efforts on sector-based and structural bills – as with the Health Reform and the NDP – but specialise in specific topics to optimise resources and position themselves as an allied actor.

Mapping relevant actors, including CSOs and experts, for progressingprioritised issues

Once those sectors that have been deemed strategic to focus on have been identified, it is advisable to map CSOs and experts who are willing to collaborate in developing technical and sector-specific recommendations with a focus on addressing corruption. Such collaboration will require a certain degree of specialised knowledge.

Despite the absence of a sector-based bill in the pipeline, it is recommended for anti-corruption CSOs to maintain a regular dialogue with sector-specific CSOs to facilitate future collaborations. Consequently, prior to the discussion of a bill, both CSOs will have greater clarity on how to develop joint advocacy strategies

Ensuring legislative advocacy activities are backed by technical research

Anti-corruption legislative advocacy should remain technical, to avoid falling into political discussions and stances. The technical approach would enable anti-corruption CSOs to approach a greater number of stakeholders in a multi-party scenario.

CSOs should clearly explain corruption risks in proposed bills and highlight the need for anti-corruption measures. This will help legislators, government officials, and citizens understand the importance of this safeguards.

Government officials

Citizen participation should not merely satisfy legal requirements. Advocacy efforts that promote the common good can significantly strengthen the legislative exercise. TpC recommends:

Strategically prioritising bills

A strategic approach must include an analysis of: the number of bills in process in each chamber; the public entities involved; the legislative procedure each bill must follow; and the legislators supporting each bill and the CSOs that can contribute to strengthening each bill – especially from an anti-corruption perspective.

This analysis allows legislators and government officials to focus on specific bills and mainstream anti-corruption efforts more effectively.

Leveraging CSOs’ expertise

Given the breadth of topics addressed in Congress, it is impossible for a single legislator to master all areas or have an advisor for each. Anti-corruption CSOs help members of Congress and government officials better understand issues. This enables deeper analysis, the drafting of anti-corruption legislation, and adjustments to the bills to strengthen anti-corruption measures.

Although CSOs traditionally offer technical assistance, it is encouraging when members of Congress and government officials seek out CSOs to contribute thematically and conceptually to their legislative work. TpC recommends using legislative vacancy periods to create spaces for thematic exchange and the drafting of draft bills.

Sharing information with citizens

Maintaining open dialogue about collaborative efforts between members of Congress and anti-corruption CSOs is essential, for fostering trust and bridging the gap between citizens and the legislative branch

Given the perception of insufficient anti-corruption initiatives in Congress, showing the joint efforts of members of Congress and anti-corruptions CSOs would demonstrate commitment to addressing corruption. Personal social networks (belonging to the congressmen and Congress), Congress’s website, media outlets, and spaces for dialogue with citizens should be used to publicise these efforts.

Clarifying the scope of citizen participation spaces

The case studies in this research highlight the need to manage citizen expectations when new participation spaces are introduced. Given the interest of participants (CSOs or non-organised citizens) for their input to be taken into account, members of Congress and government officials convening the spaces should clearly define: the purpose of the space; the participants; the methodology; and the scope and how citizens’ proposals will be assessed.

TpC also recommends including in these spaces’ agenda a specific part for identifying corruption risks. This will allow participants to make informed decisions on whether to support a particular bill or not, and adjust their inputs in future participation spaces.

Establishing strategic alliances with CSOs

Such allianceselaborate joint proposals for cooperation programmes and projects and focus on strengthening the anti-corruption knowledge of Congress members. Due to the changes in international cooperation, there are currently more opportunities for presented proposals to be implemented throughout CSOs and public bodies.

Governments, cooperation agencies, and donors