Rwanda is often presented as a success story for managing to reduce corruption in society. On closer inspection, informal and formal governance in Rwanda are interlinked and this blurs the lines between licit and illegal practices. Clientelism, favouritism, and cronyism are entrenched in the establishment and maintenance of order in Rwanda.e2e69e36fce5 Other possibly more overt forms of corruption, such as bribery or kickbacks, are much more repressed, highlighting a narrow economic understanding and application of the definition of corruption.

Corrupt practices continue mainly because of power abuses, lack of control, and interdependencies related to the state’s reliance on informal governance. This reliance corresponds to a ‘social embeddedness of public policies.’ This co-production of norms – relying on state and non-state actors – is a key generator of the co-production and continuity of corrupt practices. If this facet of corruption is not seen in international rankings, it is simultaneously related to the curtailment of free speech in Rwanda, and to the intertwining of formal and informal governance – both of which ensure less visibility of and less attention to certain aspects of corruption, as opposed to the more documented financial implications of petty corruption.

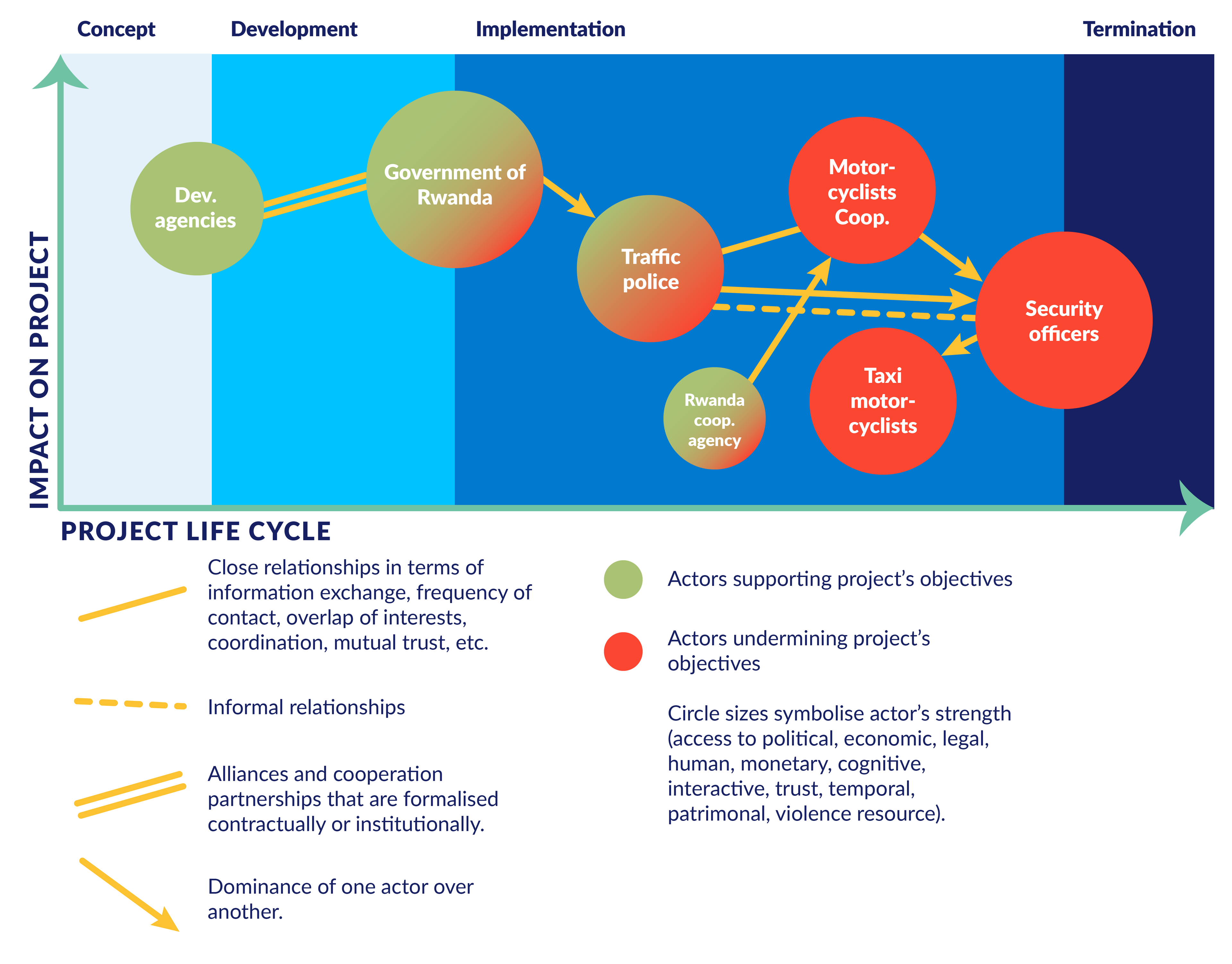

An examination of how Kigali’s taxi motorcyclists deal with corrupt security officers and police officers brings insights on how to perform a social diagnosis, to reach a more tailored policy design, and to define strategic measures, which can be devised to reduce the implementation gap. Knowing how to estimate actors’ room for manoeuvre and their ability to instrumentalise or to circumvent the administration’s oversight mechanisms may be of benefit to development practitioners and the government of Rwanda.

Looking at actors’ rationale, the relationships among those actors, and their espousal of social norms, it is possible to establish a social map of a particular environment. Taxi motorycle drivers, police officers, and security officers from taxi motorcyclists’ co-operatives in Kigali are the main protagonists under examination. Using social norms theory, it is possible to identify patterns of behaviour, determine the actors’ level of agency, and measure the conditionality of actors’ preferences and how taxi motorcyclists relate to sanctions. Put another way, a social norms approach helps identify if the corrupt practices under scrutiny are a social issue or if they correspond to mere opportunistic and individual actions. Interviews and participant observations, carried out in 2013 and 2019, were the basis for understanding the evolution of actors’ practices and their cognitive perception.

Taxi motorcycle drivers appear to be mostly involved in petty corruption practices; they can save money by paying bribes rather than expensive fines. Yet, they also face a system of extortion that is institutionalised: ‘The police and the security officers are always asking us for money. We are being milked for our money!’ Corrupt practices are supported by structural elements. This may be in the form of delegating authority to security officers, which adds another level of authority and, therefore, more opportunities for corruption as these officers are not sufficiently supervised. Interpersonal relationships and power relations also support corrupt practices. Two examples of this are security officers issuing fines in total illegality but with the tacit support of motorcycle co-operatives and the police, and the redistribution of officers’ bribes to superiors.

Interestingly, corrupt practices are also normalised through ritualised social exchanges. For example, a religious lexicon is adopted by taxi motorcycle drivers who ask for ‘forgiveness’ to access corruption. The use of context-specific vocabulary, special gestures, and cultural references all contribute to the ritualised exchanges among actors. However, corrupt practices do not correspond here to particular social norms, as actors do not develop normative expectations towards corruption. This presents possible remedial actions in a bid to implement anti-corruption measures in the taxi motorcycle sector. Rather than trying to change or create social norms, a consideration of the actors’ empirical expectations may provide the way forward. For instance, by changing attitudes through the positive promotion of the status of taxi motorcycle drivers; increasing security officers’ sense of accountability; and diminishing the incentives for bribery by reducing fines.

Social mapping (looking at stakeholders’ capacities) presents a way to better contextualise anti-corruption policies. In Rwanda, anti-corruption policies have had some paradoxical consequences for the road traffic safety policy. The withdrawal of the police force from traffic control duties opened the door for motorcycle co-operatives’ security officers to assume de facto the position of a road safety regulating authority for the taxi motorcycle drivers, without any checks and balances to curtail it. This consequently increased corrupt practices: when interviewed in 2013, approximately 85% of the 70 motorcycle drivers stated that they had paid a bribe to the police in the month prior to the survey. By 2019, only 25% of the drivers interviewed confirmed that they had paid a police bribe; yet 100% confirmed that they had bribed security officers.

Figure 1. Social map of interrelationships: National anti-corruption strategy in the road sector – main implementing actors.

- Booth & Golooba-Mutebi 2012; The Economist 2017.