The main elements for managing organisational integrity

Sascha works for a development aid agency. She arrived last week in Galta as the new manager of a project established to deliver vaccines, as a new pandemic is quickly spreading all over the country. While Galta is a high corruption risk environment, Sascha's organisation applies a zero-tolerance policy for corruption, punishing severely all instances of malpractices.

Sascha wants to ensure her team understands well ethics requirements as any corruption case could heavily impact the project’s reputation and vaccines’ delivery. Yet, she does not know how rules established at the distant headquarters are perceived and internalised by her team. She is unsure on how to best communicate on ethics policies and to motivate her team to respect the rules. Sascha is aware that the way she will manage integrity is going to impact not only the project, but also her relationships with colleagues and her own self-perception.

What are the main challenges and solutions for aid agencies to ensure the respect of ethics policies and support their employees?

Palazzo frames the concept of organisational integrity in four parts: 1) the quality of rules, procedures and activities of an organisation; 2) the relationship between employees and their organisation; 3) the integrity of employees; and 4) the ethical quality of employees’ interactions.

Thanks to interviews with development practitioners and desk-based research (see methodology below), this paper examines those interrelated elements to understand how they can be helpful to reduce corruption risks within an aid organisation. Firstly, it introduces the notion of organisational integrity, presenting the compliance-based approach and the values-based approach. It then further examines compliance, looking in particular at the implementation of ethics policies and anti-corruption training, two main tools used by donors to reduce corruption risks. The paper then examines in detail the values-based approach, looking at two framing concepts: psychological contracts and social norms. For each section, theoretical aspects and common practices are elaborated.

Ethics in the organisational culture

The different rationales related to organisational culture

Some research on business ethics acknowledge the relationship between unethical behaviour and organisational determinants. In other words, corrupt practices and unethical decisions by individuals would be (in theory) influenced not only by individual characteristics or goals, but also by social and organisational factors in the organisation. In theory, organisations with well-implemented organisational integrity would be more likely to prevent individual staff members’ malpractices and private self-serving tendencies.

While organisational integrity is related to many different aspects and departments within an organisation, a culture of integrity has been described as what holds organisational integrity together. Schein, one of the pioneers in exploring organisational culture, defined the concept as "a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration” […].926b65b673ea The concept is that employees’ attitude towards corruption is shaped by their experiences, by their understanding of rules and procedures and how values and norms are embedded within the organisation and perceived and implemented by others.

Different factors may drive people to act ethically in an organisation. Below are three examples building on the scenario with Sascha above:

1. The compliance approach

Factors characterising this approach include:

- It is a duty to comply with moral principles (to do the right things).

- Employees are autonomous decision makers following reason-based principles.

- The compliance management system safeguards that employees comply with rules and procedures.

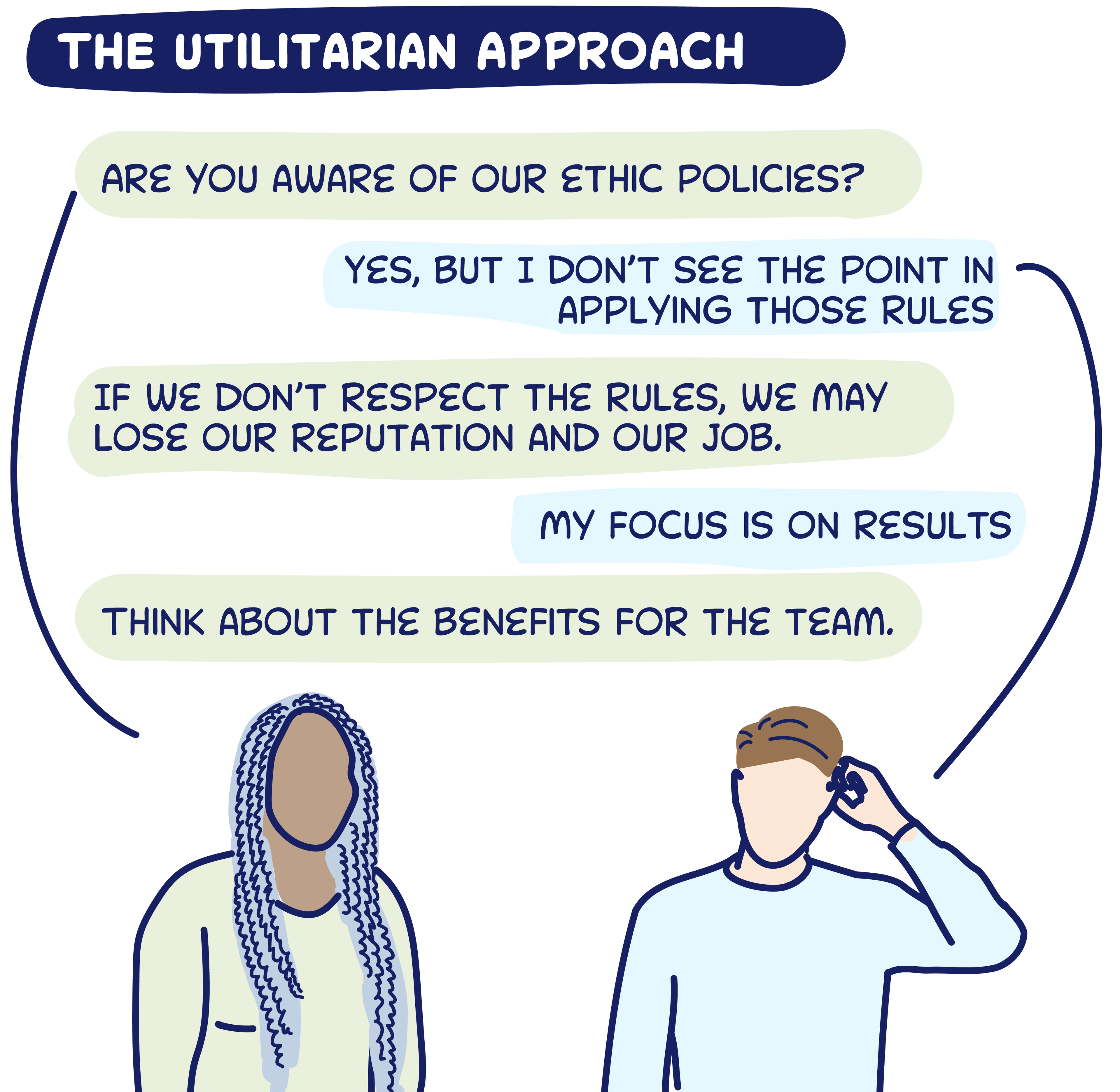

2. The utilitarian approach

Factors characterising this approach include:

- It is based on the economic benefit of an action.

- Employees are pushed to achieve a beneficial result for the social group.

- It is part of the performance system based on results. It is controversial as it relates ethics to benefits, not to moral principles. It is not followed by development aid agencies.

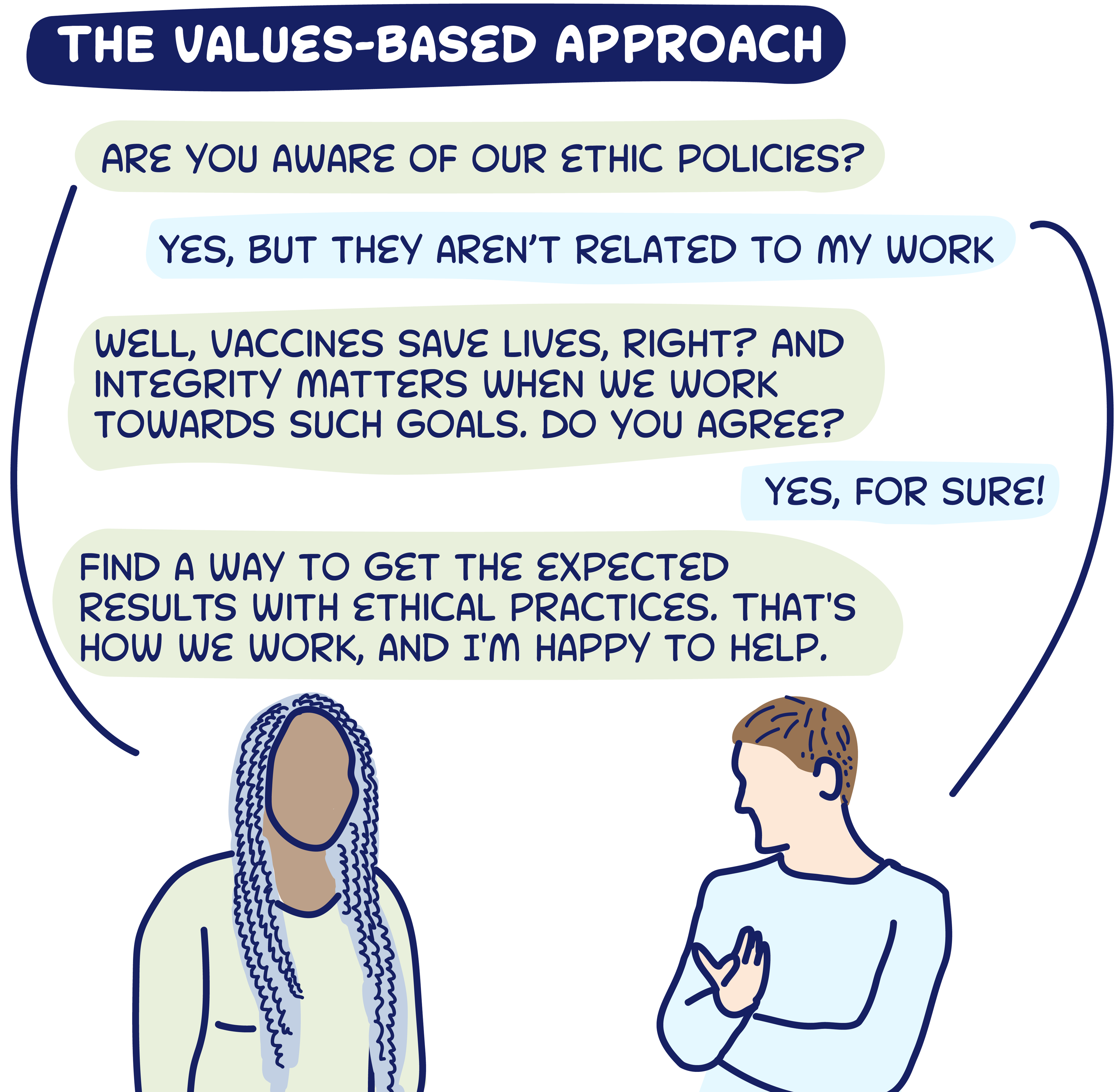

3. The values-based approach

Factors characterising this approach include:

- It focuses on the values of action.

- Employees are motivated to contribute to collective goals and to act for the worthwhile purposes and values of their organisation.

- Employees regulate their behaviour mainly by themselves and mutually. Work environment (eg perception of practices, well-being, etc.) is crucial to promote and enable good conduct.

As explained above, the compliance approach emphasises the duty to comply with integrity requirements and the need to ensure compliance is effective. The values-based approach focuses on the capacity for employees to regulate their behaviour by themselves and mutually, thanks to the active connection with collective goals and organisation’s values. In contrast, utilitarianism relates to the material benefits of an action for a social group. It will not be expanded further in this paper as it is less relevant to the operational reality of aid organisations.

The compliance approach and the values-based approach can be combined to ensure a minimum integrity standard and to motivate employees. The next section will give insights on how the compliance-based approach and the values-based approach can be implemented to develop a culture of integrity within the organisation.

The culture of integrity in practice

All organisations with budget spending responsibilities have a compliance-oriented system, with rules and processes ensuring adherence with the rules. For several development aid agencies, the culture of integrity is operationalised by the compliance system. For example, there is a long tradition of integrity management at GIZ, but it has been recently merged into a compliance and integrity unit where integrity serves the compliance system. At Enabel, ensuring organisational integrity is part of the Audit Department. Similarly, the Italian cooperation aimed at establishing a “culture of legality, ethics and integrity”, relying among other measures on a disciplinary system, a monitoring system for compliance and corruption-risk assessments. In fact, according to interviews one of the priorities for development aid agencies is to respect a legal framework for integrity, having in place an anti-corruption management system.

Formal rules are important to define ethical standards within an organisation and for employees to know what is appropriate. Yet, establishing formal rules and a control system might not be enough to enable a culture of integrity. The integrity system should also address informal norms. For example, prejudice and gender-related discrimination can be based on implicit unconscious biases and stereotypes and not only explicit harassment. As Schein explains it, building or modifying an integrity culture within an organisation requires understanding and modifying employees’ assumptions, not only behaviours. It requires developing awareness on ethics and its benefits, to drive employees to engage in ethical behaviour and finally to support employees in ethical behaviours while sanctioning inadequate behaviours.

Some development aid agencies started to introduce elements that can be related to the values-based approach for integrity. In particular, the Swiss Development Cooperation initiated a process to develop a corresponding organisational culture: “In 2018, 200 employees participated in a process on organisational culture for integrity. Several measures were identified, in particular: to create space for dialogue; to embrace a feedback culture, to reduce distance with the leadership, to define leadership principles. We even thought about organising an internal contest of the best failure to enhance the value of open communication.”b382952e8cba This approach is interesting for several reasons:

- A participative methodology can be useful to establish an integrity culture and employees’ engagement towards values, as explained for example in this handbook for employee engagement.07461b2e4f3a

- Communication influences how employees see their organisation and do their work. Patterns of communication reflect organisation’s integrity culture. An open communication is a way to develop trust and honesty (see for instance this article on integrity management).6fbe7fadd7dc

- As acknowledged by a paper on organisational integrity in the private sector, a strong engagement of the senior leadership is an important factor to drive an ethical culture. It can be based on oversight, role modelling, communication, etc.

Finally, developing an integrity culture mixes various dimensions: the individual level (eg. work recognition, rewarding ethical behaviour); interpersonal interactions (such as supporting a grievance system to drive ethical conduct); group dynamics (for example ensuring inclusivity, but also role and task clarity within teams); relationships among groups (eg. collegiality among services); and inter-organisational relations (for instance between development aid agencies and partners). Next sections will go further on how to enable corresponding environment.

Ensuring a minimum standard of integrity with the compliance approach

Implementing ethics policies

What do ethics policies look like?

In practice, ethics policies typically include aspects of compliance and values. The "code of conduct" is a typical compliance-based approach tool for integrity management. It describes procedures and what is expected from employees, from systematic monitoring to penalties for those who break the rules. For example, Australian’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) defines all integrity rules which should be respected by employees, giving a few scenarios on border lines situation and how the law applies to those situations.

A "code of ethics", on the other hand, is based on the values-based approach. It focuses on general values, rather than specific instructions on behaviour, relying on an employee’s capacity to apply moral reasoning. Rather than telling what to do, the organisation presents a framework providing general values as well as the support employees can get to apply these values. For example, the ethics charter from the French Development Agency “aims to strengthen the identity, unity and performance of the Group, facilitate the working life of employees and protect the Group and employees against the risk of reputation damage”; “it identifies a reference system for the values and meaning” related to the legal and compliance framework, with a “particular vigilance with regard to preventing corruption, notably in procurement”.68aeb86da212

Some organisations have a hybrid approach. For example, GIZ Code of Ethics defines integrity principles and values, but also describing how people within GIZ should interact among themselves and with external persons and how the organisation manages and implements those principles.

Difficulties and solutions with the respect for ethics policies

Gender is an important aspect to ensure integrity within work relationships, within an organisation and with partners. Accordingly, we could expect the aid organisations’ ethics policies to take a particular stance on gender within their ethics policies. Yet, the review of ethic policies from development aid organisations shows that most of them refer to gender only in terms of avoiding sexual misconduct and harassment. Such policies could go beyond this to embrace diversity and inclusion, and combat gender imbalances, harmful gender stereotypes, and implicit bias. Even if separate and additional gender equality policies may exist, references to gender within ethics policies can promote gender equality by enhancing benevolent attitudes, supporting gender parity in employment and promotions as well as encouraging inclusive and gender-sensitive corruption reporting and whistleblowing mechanisms.

According to interviews, one of the main difficulties to operationalise ethics policies within development agencies is their decentralised structure, across countries. For example, with more than 23 000 employees in 120 countries, 70% of whom being national staff, GIZ has to rely on its country offices to make sure that the basic messages are transferred and adapted to its different audiences. It is the responsibility of the country directors and heads of programmes to adapt rules and communication to the context and to ensure that they are properly implemented. With only a small team at the HQ level, it is very difficult for integrity managers to liaise with all heads of programme and country directors to ensure that local integrity framework is adequate.

As a way to overcome decentralisation-related difficulties and to prevent any breaches on ethics policies, Enabel works with focal points. “In each country, we have one focal point for fraud prevention, appointed by the country manager. Focal points prepare material and deliver integrity briefings and they prepare training on corruption (such as face-to-face sessions on ethical dilemmas). 75% of focal points are local staff, and they can be HR managers or financial managers. It is important to empower local staff as focal points, as they know the context and it is a better way to convey the message rather than relying on outsiders.”0497a060d078 Similarly, the French Development Cooperation use referent persons for good governance and for conformity, within regional agencies (covering several countries).

Another solution is to invest more on internal data collection on integrity issues. For example, at the New Zealand Customs Authority, “We do keep all sorts of statistics to define what particular integrity issues we might be seeing in particular groups and in what circumstances.”6f99ef78c37b That way, some implementation gaps can be detected and addressed. NZ Customs Authority is able to assess risks by category (abuse of office, conflict of interest, dishonesty, etc.), by seniority, and units, using that information to improve communication on ethics policies.

Another difficulty is that development aid agencies employ staff from and in very different socio-cultural backgrounds. Moral imperatives and ethics are not universal; the perception between what is public and what is private can vary, as well as the logic of employees. Moreover, in some contexts, staff are more likely than others to face internal pressures or external pressures from their social network. A starting point could be to define well the notion of ethics within the organisation to facilitate its operationalisation. Finding coherence and consistency between organisational ethics policies and ethical expectations from individuals is an important factor for integrity. Finding the right communication channel to facilitate correspondence between actions and values is another. For example, Sida chooses to integrate integrity discussion during annual performance assessment, between employees and their line manager. “We suggest some areas that should be discussed and it is up to managers to do it. Yet, we cannot follow up if they decided to talk about it or not.”59eed805bfe9

A related difficulty is to make sure that project staff understands how to combine the focus on results and the respect of ethics policies. On one side, most of development aid agencies need to follow a zero tolerance for corruption policy, with a clear commitment to ensure that public money is not tainted by corruption. On the other side, development practitioners connect with legitimate purposes of their organisation and outcomes of their development programme. They are engaged to deliver results, sometimes in a very adverse context. Denying their struggle would create tensions between the headquarters level and implementers, leaving alone implementers to adapt ethics policies to their context. This is why open communication on ethical aspects is important to accompany staff, as the AFD attempts to do with its ethics advisory service:

Listening to employees’ ethics concerns: best practices from the AFD

The French Development Cooperation (AFD) has developed a specific approach to support employees facing ethical dilemmas. The ethics adviser is an independent office, attached to the general management. It does not follow specific objectives and neither enforcement procedures, presenting an unusual and intriguing outlook: “While a whole process starts when employees contact compliance department, when they contact me, no process is launched: I have no power, no investigation capacities and I do not represent any directorate; I am neutral.”*

The goal of the ethic desk is to listen to the employee’s concerns and to help them build a constructive approach toward ethical dilemmas. For example, “an employee can contact me on a confidential basis before reporting a situation or a decision. The employee knows the procedure, but he wants to discuss before acting. My role is to develop awareness on consequences for acting or not acting so that the employee can take an informed decision and create the conditions to protect his integrity. Integrity is a great principle but in practice, safeguarding own integrity is based on many micro-decisions.”*

Accordingly, the ethics office is a space for free and confidential dialogue to discuss a broad range of topics: conflict of interest, toxic management, harassment or work suffering, ethical decisions, etc. "Within the AFD, we have a very dedicated and motivated staff, looking for meaning and purpose in their job. Some collective or individual decisions or situations can hurt employees’ convictions."* A neutral space for dialogue can help keep employees’ commitment and recognition of their beliefs. Of course, there are other internal spaces for dialogue on ethical aspects; yet in those instances, employees’ voice is often circumscribed by their position within the organisation.

The ethics office is also there to check for incongruities between ethics rules and their interpretation, as staff can come from very different socio-cultural backgrounds. Moreover, ethical rules can be difficult to interpret or even to apply in confusing situations. A free dialogue on ethics can help to reduce distance between headquarters’ expectations and field staff reality, avoiding potential dissents. Furthermore, it informs the organisation on potential implementation gaps or specific needs for further training or sensitisation.

* Catherine Garreta, Ethical Advisor, French Agency for Development, interview on 7 September 2021.

Anti-corruption training to enhance compliance and ethical reflection

The different rationales behind anti-corruption training

Within its recommendations on public integrity as well as a public integrity handbook, the OECD emphasises the need for integrity training to develop a culture for integrity as well as to curb and prevent corruption. Several approaches towards integrity training can be identified, with some aid agencies mixing different approaches.

The compliance-based approach enhances obedience by reasserting what are the rules and what is expected from employees. This approach can be based on individual training (eg. self-paced training) or collective learning. For the Head of Internal Audit at Enabel, training based on socialisation is the most successful because most employees are influenced by their environment, by what others do and if there is pressure to act in a certain way: “80% of staff can be influenced by training. If you tell them and repeat what are the rules, if they see others respecting rules and spreading the word on integrity, they will largely comply with the rules”.2b4531d63cfa However, the way employees perceive integrity rules can influence compliance; external incentives for action can be less efficient than inner motivation for action.

The values-based approach is based on facilitated dialogue, free discussions as a way to encourage an open communication culture and to raise employee awareness on ethical issues. In this perspective, the accent is less on deontology (the duty to respect rules) and more on the development of ethical thinking. Employees develop the capacity for active judgement on morally complicated cases, as well as the possibility to connect with ethics policies and the values of their organisation.

Anti-corruption training in practice

Several development aid agencies, such as AFD, Enabel GIZ or Sida developed compliance web-based training, explaining internal processes and regulations for anti-corruption. For example, “At the AFD all employees must follow a mandatory annual online training on fraud and corruption, which fulfilment has an impact on their annual profit-sharing bonus”.f0ff5b335350

New approaches based on socialisation are also emerging within development aid agencies. For instance, at Sida risk managers and corruption experts are the ones training their colleagues: “Our risk management and corruption experts take the lead to organise training sessions and discuss different aspects of risks related to corruption, for example sharing their experience on how whistleblowing cases are managed.”35c3721f5c79 Similarly at the AFD, a learning practice is based on peer-to-peer dialogue with other development agencies and with employees sharing expertise but also past experiences on particular risk situations: “During training, a lot of space is dedicated to exchange with colleagues. At the compliance department, we are not specialists in all sectors and geographic areas, so it is very useful to have experts explaining specific risk situations.»e5970721b50a

Another perspective is to base training on transformative dialogue, to challenge existing norms and cognitive perceptions and to empower staff to modify power dynamics they are involved in. Storytelling, ethical dilemmas training can be used as a moral compass. An example is the Swiss Development Cooperation using Theatre Forum to speak about sextortion, sexual harassment and gender. Theatre Forum is based on experiential learning, where participants watch, take part and discuss a particular situation, as a way to modify their perception on the situation and their future actions.

Whatever chosen perspective, training should be a safeenvironment for voicing questions, concerns and ideas. Yet, ensuring the right conditions for dialogue is not easy, as biases exist to free speech (social exclusion, power dynamics, cultural and cognitive differences, methodological biases, etc.). It is important to reiterate the existence of reporting mechanisms and the structural measures protecting employees’ personal integrity, to apply Chatham house rules for free speech, and to use methodologies for participative and inclusive discussions. Developing knowledge on psychological pitfalls related to corruption, and how to read the warning signals would also protect staff against integrity risks.

Considering impact is another key aspect to ensure the quality of anti-corruption training. For Sida, ensuring impact is by tailoring anti-corruption training to the experience of participants. “Within the course, participants have to see their own weaknesses for corruption risk management and to look for solutions to address those weaknesses. Follow-ups are also proposed with coaching sessions. Yet, after that our sphere of control is gone”.e6f0c201e9f3 It is in fact difficult for development aid agencies to ensure that participants internalise training content and apply it in their work.

As a way to mitigate corruption risks and pressure on employees, development aid agencies can also consider partners in their integrity training. SIDA proposes training to its Swedish partners within civil society, public agencies, academia etc. and to their international partners. This training is related to corruption risk management, corruption as an obstacle to development and the implementation of Agenda 2030 and different thematic courses (such as gender or climate).“We believe it's important that our partners are aware of those issues, to follow our guidelines but also our priorities in doing international development work.”491632cd90e0

Complementing the compliance perspective with the values-based approach

Understanding psychological contracts

What psychological contracts refer to

In a values-based approach, integrity culture can be enhanced when aligning organisation work conditions and employees’ needs and desires. One important concept to achieve this alignment is the psychological contract. Psychological contracts refer to the employee-organisation relationship. It is defined as “an individual’s beliefs regarding the terms of conditions of a reciprocal exchange agreement between the focal person and another party”.a06842fe69af In a few words, the employer-employee’s relationship is expected to be reciprocal while employees develop formal but also informal expectations towards their employer. Those expectations are based on the belief that the employer owes them material and immaterial benefits due to their contribution.

In the psychological contract’s perspective, many factors are considered to develop organisational integrity. For Rousseau, psychological contracts are based on a mix of economic and social components. In particular, work conditions are the most important factors: benefits, job security, career development, work-life balance. A study on what employees value most in the psychological contract shows that many aspects are immaterial: trust and respect, open communication, fair treatment, interesting work, equal opportunity, safe work environment, etc. A more recent study shows that breaches can occur when employees perceive a lack of support, unfairness, few resources and distrust. It is worth noting that other factors can also influence employees’ expectations, such as their level of qualification, the national context, or societal factors.

Contract breaches can also be related to gender as career opportunities and treatment can be unequal between men and women. In particular, gender-based discrimination can be based on contractual beliefs and orientation between men and women (for instance, a belief in some cultures that women are less oriented to a future in the company or less willing to go an extra mile).

Accordingly, psychological contracts are related to the broader debate on the link between work conditions and ethical behaviours. Some theoretical studies show that job security and related long-term employment enhance the development of an esprit-de-corps which in turn can limit the risk of short-term corrupt behaviours. Similarly, studies demonstrate that public servant motivation can influence the willingness to report malpractices. At the contrary, studies show that long-term socialisation and solidarity can inhibit the willingness to report on colleagues. In fact, motives for being corrupt are not necessarily based on economic gains but also love, friendship, status and the desire to impress others. Other studies emphasise the impact of meritocratic recruitment on civil servant performance but do not find any relation with salaries, internal promotion or career stability. Therefore, the connection between employment conditions and ethics behaviour remains ambivalent in the literature; it is worth keeping that complexity in mind when considering the use of tools related to psychological contract.

Applying the concept of psychological contracts

Not all development aid agencies offer job security and career perspective for all their employees. At the contrary, many job positions in development projects are based on fixed-term contracts, in relation with the project’s timeframe, available funding as well as agreements between countries. Moreover, career perspectives may be limited for local staff, as development aid agencies are mainly government organisations which may reserve positions only to their national staff. This situation may have consequences on employees’ perception of their psychological contract and consequently their attitude towards integrity. In particular, employees without career opportunities are less likely to have psychological safety, so it might impact their capacity to speak up and raise concerns. For example, a laboratory experiment with employees from the private sector shows a link between psychological contract breaches and the willingness to report fraud. Reciprocity, financial sustainability, and outcomes of previous reports of unethical activity are the main drivers for fraud reporting intentions.

Development aid agencies employ a wide range and a diversity of employees in the delivery of aid. Some development aid agencies make a distinction between their local and international staff, in particular on salary and economic incentives. Of course, defining pay levels for different kinds of personnel is a complex issue. It is not viable to transform salary policy solely in the pursuit of psychological contract’s integrity. Yet, aid agencies should keep in mind that differential wage structures could undermine integrity. Communicating appropriately can help to reduce the perception of unfair treatment and to minimise risks to damage relations between employees and with the organisation.

While psychological contracts are not as such discussed withinpolicy or practice by any of the agencies, some agencies consider ways to link work conditions and the support for the integrity culture. Global Affairs Canada provides a good example:

The management of Values and Ethics at Global Affairs Canada

Global Affairs Canada has an Inspection, Integrity and Values and Ethics Bureau. It includes a Missions inspections division conducting on-site and virtual assessments (when travel is not possible) involving all employees working abroad. “We look at a broad set of criteria: leadership, governance, ethics knowledge, management of response to address allegations of malfeasance, but also work satisfaction, workload, morale, etc. While the first preoccupation for inspections is to ensure good conditions to achieve objectives, inspections can also inform on ethics internalisation by employees and their well-being”.* Inspection division is independent, ensuring data privacy and objectivity in the conduct of data collection. Anonymised results are shared with the Heads of Mission and programme areas. Recommendations also inform program areas, training objectives and the Values, Ethics and Workplace Wellbeing Division.

The Values, Ethics and Workplace Wellbeing Division is also part of the Bureau. Its Values and Ethics Unit promotes awareness of the department’s Values and Ethics Code and Conduct Abroad Code, which outlines core values and expected behaviours to support a healthy and effective workplace. “Personal development, competency and awareness are key to building confidence in ethical decision-making as well as an internal motivation to act ethically. It is also important to work towards building a stronger culture of integrity and a better organisational climate, as opposed to relying on rules to be enforced by the organisation.”** Moreover, the Division includes an Employee Assistance Unit offering counselling services, and an Informal Conflict Management Unit; both can provide important support to employees facing difficult situations.

* Michel Lacourcière, Deputy Director, Mission Inspection Division at Global Affairs Canada, interview on 8 November 2021.

** Jessie MacNeil, Deputy Director, Values and Ethics Unit at Global Affairs Canada, interview on 22 October 2021

Another perspective is to connect employee motivation with the mission or purpose of the organisation. For example, a study on public servant motivation shows that public servants are more willing to report wrongdoing when they can connect to values and contribute to the common good and that public servant motivation can be stimulated. While New Zealand Customs Authority is not a development aid agency, it stands out as a lone example of a public organisation connecting the values-based approach not only to the work environment conditions but also to the worthwhile purposes of the organisation:

The use of psychological contract in New Zealand Custom Authority

The psychological contract approach at New Zealand Customs authority is based on both material and immaterial aspects: “Psychological contract is our underlying principle. We offer flexible working arrangements, a genuine commitment to diversity and inclusion, a solid pay and recognition for work, and a high trust environment for all our employees. In return, we expect employees to come and do a good job, operate with integrity and maintain the reputation of customs. As a result, we have a very low attrition rate, around 6%,”* which corresponds to half of the turnover in NZ public services in 2018.

The organisation puts a strong emphasis on values to generate integrity commitment: “What is part of our contract is an opportunity for people to protect and promote New Zealand. Employees can be very proud about wearing the uniform.”* This values-based approach is based on psychological contract, but also peer pressure: “As we have such a strong reputational and integrity base, the peer pressure is innate.”*

This peer pressure and strong focus on values can on occasion generate downsides, in particular on reporting malpractices: “Because we have a base level of trust and confidence from the public, because we have a solid reputation, it can be hard for some to send that message. Officers don’t want to be the one that creates reputation damage and they may not be willing to report on something relevant. Moreover, some people have an aura and that means others are reluctant to report an issue to those people; they feel they may be targeted.”*

* Janine Foster, Director Risk, Security, and Assurance, New Zealand Customs Service, interview on 2 July 2021

In summary, psychological contracts show that fulfilling employee’s needs and expectations, ensuring a safe and fair work environment, connecting with motivational drivers can support an integrity culture and can drive towards ethical behaviours. Accordingly, considering employee’s well-being and work satisfaction could inform corruption risk identification processes. Next section will go further on how to manage social dynamics.

The Social norms approach

Social norms are accepted standards of behavior, prescribing or proscribing behavior within social groups.0e3c92d3bc78 Accordingly, individuals face normative pressure to behave in certain ways.

For integrity in the health sector or for tackling gender inequalities, social norms theory is used to induce change at the group and individual level. It supposes understanding what support such norms and how norms can be altered.In particular, Bicchieri emphasises the role of social proximity and repeated interactions for norm compliance. In that perspective, diagnosing internal or external normative pressures in a given context is a way to evaluate group conformity towards ethical and unethical principles. Following her reasoning, practices follows social norms when:

- Individuals behave in a certain way to conform to a descriptive norm (eg. “I do it because I believe others do the same.”). It creates interdependencies among individuals to respect those empirical expectations;

- Individuals have normative expectations (eg “I do it because other people expect me to”); It corresponds to an injunctive norm to respect a collective belief to act in certain ways;

- Social sanctions apply when behaviour is different from the norm.

Operationalising the social norms approach

There is a growing attention3a6c977a7a1c to consider socialisation to enhance compliance with ethics policies. However, while social norms theory offers a real potential, “a lot has to be done to operationalise social norms theory”.237f58da8aa7 Up to our knowledge, no development aid agency uses the social norms approach to curb corruption within its own organisation. Measuring changes requires a baseline and regular evaluations of different variables: personal preferences, perception of descriptive norms, perception of injunctive norms, and behaviour. Those different metrics require lots of information, and triangulation is important (eg. interviews, surveys and focus groups). “The best way to introduce social norms approach within organisations would be to incorporate it into existing processes for corruption risk management and/or ethics management.”a5c81fb95cbd

Attitudinal integrity surveys are a way to collect data on the employee’s attitude towards the compliance system, as well as morale and engagement towards the organisation. For example, a study on the US police integrity asked police officers to evaluate cases of police misconducts, assessing the seriousness of offences, their perception of discipline and willingness to report. Another method tries to capture employees’ attitude towards integrity by assessing specific contexts, behaviours and perceived consequences of their action.

Those integrity assessments can help employees to understand what constitutes integrity in their work environment and to activate the appropriate attitude towards corruption. For example, when asked whether “a gift should be accepted when necessary”, it recalls the need to respect ethical policies. If employees did not develop a strong attitude towards gifts, they are more likely to withhold judgement (eg. answering a neutral option), informing the organisation about employees’ knowledge level on ethics policies and the need for reinforcement. According to recent studies, gamified assessment are promising tools to measure bribery behaviour and attitudes, as decisions taken during gameplay are correlated to the ones taken during real-life situations and they are more interactive and appealing than “traditional” assessments. For example, the Amsterdam Leadership Lab has developed a serious game called Building Docks to assess integrity risks in the workplace.

Social norms can also be integrated within management processes to support integrity culture. In line with the values-based approach, ethics leaders (eg. through role modelling) have a key role to influence integrity culture and to vehicle integrity-related values. Trendsetters and policy entrepreneurs can also take on a crucial role of dealing with group pressures and supporting adequate social norms. As mentioned earlier, the focus persons used by Enabel to develop awareness on ethic policies, or the referent persons for good governance and for conformity at the AFD are good examples of policy entrepreneurs to enhance compliance with ethic policies.

Finally, social norms approach can also be used during ethics training discussions. Themes can question normative stakes and implicit biases on cross-cutting ethical issues, such as on gender, fairness, impartiality. Focus groups (for instance on sociability pressures), the use of vignettes, values training can be useful to enhance adequate normative environment and corresponding behaviour. For example, an experiment with civil servants in Burundi shows that communicating messages on professional values of integrity increase moral costs and prompt fairer service delivery.

Enhancing integrity by combining approaches

The compliance approach: obedience but not always integrity culture

The compliance approach can rely on well-known mechanisms to get obedience from individuals, through control (from the leadership and peer pressure) and sanctions in case of integrity breaches. This formal approach is necessary for development aid organisations to comply with legal frameworks and to structure integrity management. Development aid agencies embrace related practices to ensure a culture for integrity and structural conditions to protect staff personal integrity. While this contractual approach brings clear advantages in terms of standardisation, it can be difficult to apply in certain contexts. Moreover, it can generate a superficial adherence to organisations’ integrity norms as it remains an external incentive for individuals to adhere to integrity rules. It is important for aid organisations to ensure that support functions (such as anti-corruption training, ethics advisory services) are close enough to employees so that they connect to and apply ethics policies.

The values-based approach: trust and well-being for enhancing integrity

The values-based approach attempts to build a trust-based relationship between employer and employees. It means for organisation to rely on a different mode of regulation, not based entirely on vertical control but on employees’ self-regulation and on the confidence in their capacities to act ethically. It is also a way for employees to connect with the legitimate purposes and values of their organisation and to develop ownership to apply ethics policies. Development agencies use that approach to enhance an integrity culture based on open dialogue, to develop active moral judgment and to ease the implementation of ethics policies. Drawbacks also exist, such as the fear to report when staff get scared to damage organisation’s reputation or to confront their peers.

In a values-based approach, models such as ‘psychological contracts’ could offer a means of improving integrity management. Answering employees’ expectations, providing space to listen to employees’ concerns and needs, and ensuring fair work conditions for all employees could help build employees’ commitment and respect for ethics policies. Distress in the workplace could be considered as an additional red flag for corruption risk prevention. Similarly, the social norms approach presents attractive indicators to detect and to prevent corruption risks, looking at attitudes towards corruption.

In conclusion, employee’s engagement can be achieved by enabling a virtuous work environment, considering employee needs and desires. Values-based approaches are worth considering as a complement to compliance approaches to build an enabling environment and to reduce the risk of malpractice and corruption.

Enabling an integrity-based environment

- Indicators related to employee’s well-being and work satisfaction should inform corruption risk identification processes.

- Shifting the focus from the individual to the network in the design of anti-corruption policies is a way to better consider organisational and social factors related to corruption.

- The promotion of integrity within development aid organisations can be heightened giving more attention to gender, in particular within ethics policies (promoting gender parity in employment and encouraging inclusive and gender-sensitive corruption reporting and whistleblowing mechanisms) and training (for instance, by tackling implicit biases).

- Schein 1997, p.17

- Andrea Siclari, Knowledge Learning Culture, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Interview on 07/07/2021.

- Schneider 2010, p.160.

- Heywood et. Al. 2017, p.26.

- Agence Française de Développement, Ethics charter AFD Group, 2017.

- Patrick Risch, Head of Internal Audit at Enabel, Interview on 05/07/2021.

- Janine Foster, Director Risk, Security & Assurance, New Zealand Customs Service, Interview on 02/07/2021.

- Carolina Miranda, Programme manager, Unit for learning and organisational development, Swedish International Development Agency, Interview on 01/10/2021.

- Patrick Risch, Head of Internal Audit at Enabel, Interview on 05/07/2021.

- Yves Picard, Director of the Compliance Department, French Development Cooperation, Interview on 07/09/2021.

- Lena Fassali, Programme manager, Swedish International Development Agency, interview on 10/08/2021.

- Emilie Loiseau, Anti-corruption officer and Legal advisor for the French Development Cooperation, Interview on 07/09/2021.

- Lena Fassali, Programme manager, Swedish International Development Agency, interview on 10/08/2021.

- Ibid.

- Rousseau 1989, p.123.

- See for instance Hechter 2001, p. xi.

- See for instance Mungiu-Pippidi 2017.

- Claudia Baez Camargo, Head of Public Governance at the Basel Institute on Governance, interview on 30/06/2021.

- Ibid.