Query

Could you please provide an overview of the land corruption risks that could undermine the implementation of the EU deforestation regulation (EUDR)?

Caveat

The author has used the large language model (LLM) Claude for language editing in the drafting of this Helpdesk Answer.

At the time of writing, the timeline and other aspects of the implementation of the EU regulation on deforestation-free products (EUDR) were being debated by Member States. The author has attempted to provide an account of these development as of the end of November 2025, but notes that the planned implementation of the EUDR may be subject to further change

Introduction

Forests cover approximately 32% of the planet’s total land, supporting biodiversity, storing carbon, regulating rainfall patterns and providing livelihoods for 2.6 billion people (FAO 2025). Despite their vital role, and although deforestation rates declined globally between 2015-2025, forest loss persists as a major concern in many tropical and subtropical areas globally (FAO 2025).

Forest loss includes deforestation and forest degradation (FAO 2018:6; FAO 2025:110). Agriculture alone drives about 90% of this forest loss (Fripp et al. 2023: 6), with timber, palm oil and cocoa being significant drivers. Other drivers include climate change, logging, infrastructure development and fires, underpinned by broader economic, institutional and demographic factors.

The European Union deforestation regulation (Regulation (EU) 2023a/1115 –hereafter EUDR) represents an ambitious attempt to balance the European Commission’s trade objectives with environmental and climate goals by preventing deforestation-related commodities and products from entering the European market. It responds to evidence that EU consumption is a significant driver of global deforestation. Between 2005 and 2017, EU imports were linked to 16% of deforestation associated with international trade, with previous regulations proving insufficient because they focused narrowly on illegal logging rather than addressing all forest loss drivers (European Commission 2021b). To understand the challenges the EUDR may face, it is important to consider how forest land is managed in commodity producing countries and throughout their supply chains.

The scale of public forest management6b58d4ef39ba makes good governance crucial. Approximately 73% of the world’s forests are publicly owned and managed by governments. The level of control these public officials exert over decisions on forest classification, land allocation and the issuance of permits creates opportunities for corruption (UNODC 2023: 7). Land corruption in the forest sector encompasses a range of illicit practices in land administration and management, from bribery and opaque land deals to embezzlement, with a risk “to undermine the framing, implementation and subsequent monitoring of policies aimed at conserving forest cover” (Transparency International 2016: 9).

Research from Transparency International highlights that land corruption is a worldwide challenge, with additional demand for land, including from climate-based solutions, potentially aggravating pre-existing corruption risks (Maslen 2023). This issue is particularly relevant to the implementation of the EUDR that mandates proof that products do not originate from recently deforested land. Although the EUDR mentions corruption only briefly, it represents the first EU-level recognition of corruption as a driver of deforestation (Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023). Addressing land corruption can also help fulfil some of the EUDR’s other stated priorities such as protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples given that their access to ancestral forest lands may be obstructed by corrupt land transactions.

Accordingly, this Helpdesk Answer examines how land corruption risks may undermine the implementation of the EUDR. It provides an overview of the EUDR regulation itself, identifies documented corruption patterns in forest-risk commodity sectors and examines how these threaten the EUDR’s core requirements. Finally, it reviews proposed mitigation measures that operators, relevant authorities and oversight bodies (including civil society) can adopt to mitigate these corruption risks. Although the EUDR has only recently come into force and there is little direct evidence of its implementation, known corruption patterns in the sectors it covers show where the key vulnerabilities are. The brief provides evidence from across regions where governance challenges intersect with significant forest-risk commodity production.

Overview of the EUDR

The EUDR is a recent EU legal instrument which aims to ensure that key agricultural products sold in the European market do not drive deforestation or forest degradation, therefore strengthening the EU’s contribution to global climate and biodiversity goals (European Commission 2023b).

The EUDR replaces existing regulations such as the forest law enforcement governance and trade (FLEGT) regulation and the timber regulation (EUTR) that addressed deforestation by focusing exclusively on timber, specifically on illegal logging4b0f1dff06c1 as a main driver.

In contrast, the EUDR targets seven high-risk supply chains contributing to forest loss: cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy and wood, and their derived products. Both raw materials (e.g. timber) and finished products (e.g. furniture) must comply. In case of final products containing multiple regulated commodities (for example, chocolate with soy derivates), each supply chain must comply.

The EUDR combines legality and sustainability requirements. Operators and traders must comply with local laws and prove that products entering the EU are deforestation-free by EU standards, closing the gap that previously allowed unsustainable yet “legal” deforestation to continue (Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023: 301).

Box 1: Key definitions

Deforestation: conversion of forest to agricultural use. Forest conversion for non-agricultural purposes, such as road construction, falls outside the scope of the regulation.

Deforestation-free: commodities produced on land that has not been deforested or degraded after 31 December 2020 are considered deforestation-free.

Degradation: the gradual changes in forest structure that reduce biomass. This includes the conversion of primary forest into other wooded land, or into plantations or planted forest.

Forest-risk commodities: an alternative term to deforestation-free that reflects the wording of the UK Environment Act (2023), referring to commodities produced on land subject to illegal deforestation.

Primary forest: naturally regenerated forest of native tree species, where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes are not significantly disturbed

Operator: under the EUDR, an operator is any individual or legal entity engaged in commercial activity that places relevant products on the market or exports them.

Trader: traders are those distributing and selling products in the EU market.

The EUDR came into force in June 2023, but subsequent political debates have delayed its implementation. Following calls from EU agriculture ministers in July 2025 for simplification, the European Commission proposed in October 2025 a simplified regime for micro and small businesses and downstream operators. This proposal requires approval by the European Parliament and the European Council. In November 2025, the European Parliament voted to postpone EUDR implementation until the end of 2026, with an additional grace period for small businesses until 30 June 2027. The European Parliament also voted to open a review window for the EUDR, making it possible that the regulation would be subject to further amendments over 2026 (RFI 2025). The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) and other CSOs have raised concerns that delays and proposed amendments will water down the provisions of the regulation and reduce its level of ambition (EIA 2025).

How it works

Article 3 of the EUDR sets up a due diligence framework4ede51646444 that defines three essential conditions for products entering the EU:

- Deforestation-free: they must be deforestation-free, that is, they are not produced from land deforested or degraded after 31 December 2020. Commodities produced on deforested or degraded land before this date are exempted.

- Legality: they comply with the relevant laws of the country of production. The EUDR lists the relevant kinds of laws including land use rights, environmental protection and labour laws, along with anti-corruption regulations. Human rights protected under international law and the principle of free, prior and informed consent for Indigenous peoples are also included.

- Due diligence: the operator/trader has performed due diligence and submitted a due diligence statement electronically through the EUDR information system. The due diligence is a three-step process:

- collecting information to prove the product is deforestation-free and legal

- assessing risks of non-compliance, that is, demonstrating that the information gathered has been checked against the risk assessment criteria

- justifying how they determined the risk level and adopting adequate mitigation measures in case of risk

A key tenet of the due diligence system is supply chain traceability. In practical terms, this means that operators and traders are required to map plots at farm or polygon level,a20464b5e85c link geolocation data to each shipment entering the EU, verify that production did not cause deforestation and complies with the relevant legislation of the country of production, and attest this in the due diligence statement. Operators must be aware of the applicable legislation in each country they source from. Relevant legislation includes national and regional laws, as well as international law, such as multilateral and bilateral treaties and agreements that apply in domestic law. This encompasses land use rights, environmental protection, forest management, third-party rights, labour and human rights, tax, anti-corruption, trade and customs regulations, but only when these laws specifically affect the legal status of the production area or link to EUDR objectives.

Operators must demonstrate that documentation is verifiable and reliable, including considering corruption risks in the country of production. The European Commission’s (EC) guidance (2025a) further clarifies:

‘Relevant documentation is required for the purposes of the risk assessment pursuant to Art. 9(1)(h) and 10 of the Regulation. Such documentation may, for example, consist of official documents from public authorities, contractual agreements, court decisions or impact assessments and audits which may have been carried out. In any case, the operator has to verify that these documents are verifiable and reliable, taking into account the risk of corruption in the country of production.’

Where corruption levels are high, operators should conduct enhanced verification using additional evidence such as independent audits or forensic tracking methods. Downstream operators must also verify that upstream suppliers have properly conducted this legal due diligence (European Commission 2025b).

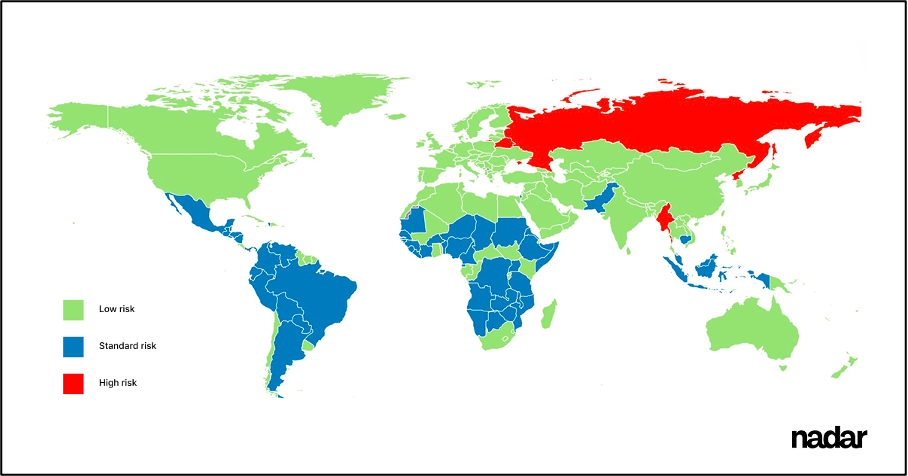

In October 2025, the EC proposed simplification measures by removing due diligence requirements for downstream operators and traders once products are already in the EU market, and by allowing micro and small-scale primary operators in low-risk countries to comply through simplified, lighter procedures. These measures are tied to the benchmarking system that the EC introduced in May 2025. Accordingly, countries are classified as low, standard or high risk based on deforestation linked to commodity production (Busse 2025).

Figure 1: map of EUDR country risk benchmarking scores given by European Commission in May 2025

Source: Busse 2025

This ranking guides businesses and enforcement authorities in conducting due diligence, with higher-risk countries facing more severe and strict checks (Li et al. 2025). As of November 2025, these proposals were not yet adopted and require approval by the European Parliament and Council. Some analysts and non-governmental organisations argued that the proposed changes could weaken the due diligence system and the regulation’s effectiveness (EarthSight 2025).

To enforce the EUDR and provide oversight over operators and traders, EU member states’ competent authorities are responsible for enforcing compliance, conducting checks, and ensuring that operators meet due diligence (Li et al. 2025). Penalties are also envisaged and include the confiscation of products, fines proportionate to annual turnover and market exclusion (Li et al. 2025). Countries of production are also affected by the stricter requirements on sourcing practices, which may necessitate changes in land use management, documentation and supply chain monitoring to maintain access to the EU market (Li et al. 2025).

Land corruption

Transparency International defines land corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain in the administration, allocation, use and control of land and natural resources”(Transparency International 2024b: 3). Within the forestry sector, corruption operates at multiple levels and across the entire value chain. Both high-ranking institutional officials and private actors can be involved in corrupt behaviour. Examples include but are not limited to:

- land registry officials fraudulently issuing titles to facilitate land grabs or legitimise illegal occupation

- politicians allocating forest concessions to companies they secretly control

- forestry officials accepting bribes from private actors to ignore illegal logging in a protected area

Transparency International, alongside organisations such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), has contributed to a better understanding of corruption risks in the land sector, including in regions with weak governance and extensive tropical forest. These contributions highlight that forests are particularly vulnerable because of their high economic value, insecure or contested tenure systems, conflicting public-private interests and limited oversight in remote areas (UNODC 2023: 13). The high level of discretionary decision-making concerning land use creates opportunities for fraud and abuse, such as timber laundering. Timber laundering, or “timber-washing”, refers to the practice of disguising illegally harvested wood as legal by, for example, mixing it with legitimate stock or falsifying documents. In this way traffickers can move illegal timber through legitimate supply chains and into international markets (UNODC 2023: 31–39).

Other forms of corruption that often facilitate ongoing abuse include petty bribery, that is, payments to officials to overlook violations or expedite approvals. The links between corruption and discrimination often mean that corrupt systems undermine land rights, drive evictions and exacerbate inequality, harm Indigenous people and ultimately contribute to forest loss (Transparency International 2024b:5–6). One of the most dramatic consequences of corruption in the cocoa industry, for example, is the ongoing use of child labour and human trafficking, as documented in West Africa; corruption exacerbates this issue because local officials may accept bribes to ignore violations, and companies may falsify paperwork to hide illegal practices (Soma Cacao 2024).

Corruption is a significant driver of forest loss, operating across local, national and transnational governance levels. This means that corruption does not operate in isolation at any single level, rather it creates interconnected pathways where local bribery enables illegal land conversion; national-level corruption provides legal cover and protection for forest-risk commodities production; and transnational networks launder the proceeds and create markets for products linked to forest loss (UNODC 2023). Recent literature exploring the causes of deforestation has brought attention to corruption’s pervasive influence across different contexts, showing how countries with higher perceived corruption tend to experience greater deforestation rates (Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023; Cozma et al. 2021; Koyuncu & Yilmaz 2008). Cisneros and Nuryartono (2021), for example, examine how forest conversion in Indonesia is shaped by complex political, clientelist dynamics and palm oil price cycles. They look at how the country's decentralisation reforms implemented during the palm oil boom, created financial incentives for local political elites to support forest conversion. They note that deforestation increases around the time of mayoral elections, suggesting that local political actors leverage the lucrative palm oil sector for short-term electoral gains, often resulting in an increase of forest loss, with political and economic incentives reinforcing each other, especially when elections coincide with favourable palm oil market conditions (Schütte & Syarif 2020; Box 3).

Politically connected elites and officials use shell companies and nominee arrangements to obscure ownership of forest conversion operations, enabling them to profit from deforestation while evading accountability. As illustrated in Box 3, opaque corporate structures facilitate illegal or irregular permit issuance, with significant environmental and social impacts. The absence of beneficial ownership registries facilitates such practices as the ultimate beneficiaries remain hidden from operators, enforcement authorities and civil society oversight (UNODC 2023: 54).

Corruption often marginalises communities by denying them access to information, consultation or legal recourse. This makes it easier for companies or politically connected individuals to seize land or secure irregular concessions, pushing deforestation into customary or Indigenous territories (Johnson & U4 2020). Finally, weak institutional conditions, especially low salaries for forest officials and remote working environments, create strong incentives for corruption (UNODC 2023, p 22).

Together, these dynamics show how corruption actively drives forest loss, both by enabling illegal activities and by shaping land uses, incentives and enforcement outcomes in ways that favour deforestation. While the EUDR does not refer to the concept of land corruption per se, it is relevant given that forestry and the seven specific commodity sectors are all vulnerable to corruption; furthermore, the presence of corruption can mean that the due diligence requirement of the EUDR will not be fulfilled for a product, making it imperative that operators and traders screen for land corruption risks.

How corruption could undermine EUDR compliance

By integrating anti-corruption laws of producer countries within its due diligence framework, the EUDR represents an ambitious attempt to link European consumption to global deforestation and an important step forward in recognising corruption as a driver of deforestation. However, its success depends on the integrity of systems such as land registries, permit processes and supply chain documentation that may be compromised by corruption in the production countries or throughout the supply chain, potentially undermining the regulation’s ability to effectively prevent deforestation-linked products from entering the EU market.

As of November 2025, the implementation of EUDR has not started, meaning there is no evidence on corruption undermining compliance with the EUDR. Nevertheless, documented corruption patterns in some of the commodity sectors covered under the regulation, as well as its compliance mechanism, suggest that the EUDR may face corruption vulnerabilities.

Corruption risks in traceability

Traceability is at the heart of the EUDR, and it is critical to help operators and traders identify and manage supply chain risks. Operators and traders must provide geolocation data37aa8085ddc4 and detailed supply chain information to demonstrate that commodities were produced in deforestation-free areas. However, in sectors with extensive intermediaries, informal production practices and weak land administration, documentation can be manipulated.

Corruption can undermine traceability through three mechanisms. First, manipulation of official records, including land cadastre, concessions and cooperative lists, facilitates illegal land conversion, as documented in Indonesia (UNODC 2023: 31-39). In Papua New Guinea, weak governance and corruption heighten the risks inherent in complex supply chains where transshipment and indirect export0d6eed571718 are common, making the timber trade increasingly opaque and contributing to serious breaches of Indigenous customary land rights (Global Witness 2017). Second, forged origin documentation allows commodities from protected areas to enter formal supply chains. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, investigations documented the widespread use of falsified cooperative cocoa fairtrade certificates (Reuters 2024). Third, payments to forestry officials enable illegal cultivation in protected areas to go unreported. For example, in Vietnam forest protection staff turn a blind eye to illegal logging in return for payments (Cao 2018), while Indonesian authorities were investigating a trend of underpayment of fines by companies that operate illegal plantationsin the palm oil sector (Jong 2024).

Moreover, fragmented supply chains create opportunities to mix legal and illegal products. An EarthSight report (2024) documented how Brazilian soy linked to deforestation and land grabbing was laundered through complex global supply chains and entered European meat and poultry sectors, demonstrating that laundering can occur far beyond the country of production. More specifically, the investigation showed that soy grown on illegally cleared land was exported by major global traders and used in animal feed supplied to European poultry companies. Although the underlying illegality occurred in Brazil, the laundering was reportedly facilitated by actors well beyond the producing country, including international commodity traders, European feed producers, large poultry processors and leading EU retailers.

Box 2: Indirect intermediaries in Côte d’Ivoire’s supply chains

In Côte d’Ivoire, one of the world’s largest cocoa producers and exporters, the cocoa supply chain is characterised by indirect sourcing through intermediaries, as opposed to direct sourcing from producer cooperatives. Only about 40% of cocoa is easily traceable, making it difficult to determine the origins of the remaining supply and assess its associated deforestation risks.

Intermediaries frequently mixed cocoa sourced from protected forests with legal batches. Traders then obtained falsified origin certificates through small payments to local officials, allowing illegally produced cocoa to enter formal supply chains.

The persistence of practices such as opaque intermediary networks and document forgery means that falsified coordinates and forged cooperative certificates could create an appearance of compliance while actual production continues in protected forests (Mighty Earth 2017; Kroeger et al. 2021).

Corruption risks in legality validation

The EUDR legality requirement can be undermined by opaque land records and non-public permits, which make it difficult for operators to demonstrate compliance. Products may appear “legal” because permits are formally valid, but they have been obtained through corrupted processes that operators’ document reviews cannot easily detect. The most direct threat arises from political capture of licensing processes, where officials with discretionary licensing authority issue permits to politically connected applicants who fail to meet legal requirements. The case of Indonesia presented in Box 3 exemplifies how weak regulations and uncertainties in the law were exploited to favour economic and political interests, leading to serious legal abuses and the violation of human rights (Colchester et al. 2006).

It is important to note that where corruption violates local anti-corruption laws, such acts would directly render production illegal under the EUDR’s legality requirement. Operators must therefore assess corruption risks as part of their due diligence wherever such laws exist. However, the more fundamental challenge arises in contexts where corruption operates within or manipulates the legal framework itself, rather than simply violating it. In such cases, the EUDR's reliance on formal legality as a baseline may be problematic as the domestic legal framework may have been compromised to mask illegality as legitimate compliance.

Stassart et al. (2025) carried out a review of land and tenure laws as well as land grabbing practices in the Amazon and the Matopiba regions of Brazil and found evidence of a recursive relationship between corruption and legality. They found that land grabbers are able to capture and hijack processesintended to protect property rights such as tenure formalisation, enabling them to give their logging plantations the veneer of legality.

Four mechanisms in particular compromise legality validation. First, retroactive legalisation allows illegal land occupation to be formalised. In Brazil’s Amazon, public forests are often illegally registered via the rural environmental registry (CAR) with the aid of corrupt notaries or registry officials (IPAM 2020; Imazon 2023). Second, selective or inconsistent enforcement of environmental laws enables politically connected actors to bypass regulations. Investigations in Brazil show that manipulation of CAR registrations allows land grabbers to avoid penalties, highlighting weak accountability (Mongabay 2023). Third, forged or manipulated documents facilitate illegal trade. In Myanmar and Papua New Guinea, bribery and falsified permits are reportedly widely used to launder timber and circumvent export controls (UNODC 2024; Global Witness 2021). Finally, large-scale corruption in forest concessions occurs where “shadow permits” are granted with minimal oversight, allowing collusion between officials and companies, as documented in Cameroon, Liberia and the DRC (Global Witness 2017).

Box 3: Political capture of the licensing process in Indonesia

During his tenure in the 2000s, the former governor of the East Kalimantan province in Indonesia bypassed mandatory administrative and legal procedures to grant logging licences to 11 companies that failed to meet the requirements for such permits and were linked to him personally. He abused his position to exert pressure on the officials responsible for issuing the licences. These licences authorised the clearing of more than 1 million hectares of forest to make way for a palm oil plantation.

To achieve this, the governor issued an agreement for land development and wood use on behalf of the companies, despite lacking the authority to do so. The companies concerned did not submit any of the documentation required to obtain the permits, including plantation boundary records, commercial forest concession documents or a feasibility study for the plantation, among other materials. The resulting loss to the state amounted to US$24.6 million (UNODC 2023: 36; Schütte and Syarif 2020).

Corruption risks in due diligence

Under the EUDR, due diligence requires operators and traders to collect complete and verifiable data as well as submit a risk assessment. However, there can be risks that the data and information operators rely on have been falsified. For example, investigations by Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) reveal that in Myanmar’s teak sector high-grade logs are routinely mis-graded with the complicity of grading officials, allowing subcontractors to launder premium timber (EIA 2024, pp.10–12). Auditors and inspectors may be bribed or co-opted to provide favourable reports (EIA 2024, pp.8–9), further compromising the integrity of compliance checks. Corruption risks in the supply chains are often neglected, as illustrated by the Dutch teak case in Myanmar (Box 4), where customs and courts found that traders had failed to account for such risks (Schütte and Syarif 2020: 15; UNODC 2023:50).

On the other hand, procedural compliance risks arise when operators rely on document verification without investigating whether underlying governance systems are compromised, as illustrated by the case study in Box 4. Operators can meet formal EUDR requirements, that is submitting due diligence statements, collecting documentation, conducting risk assessments, without interrogating whether underlying land registries, permit processes or enforcement systems are compromised by corruption.

Box 4: Failure to assess corruption risks in teak supply chains in Myanmar

In 2018, a Dutch court ruled against a Netherlands based importer of teak from Myanmar for failing to comply with the due diligence obligations required under the EU timber regulation. The company had imported 19,680m³ of teak for use in luxury yacht production without securing the necessary import documentation or verifying the legality of the timber prior to shipment.

The court of the Hague found that the importer had not carried out a corruption risk assessment, despite the well-documented high-risk nature of Myanmar’s forestry sector. The timber in question originated from an area where logging had previously been prohibited by national authorities, further heightening the risk of illegal sourcing. The court also noted that Dutch authorities had already warned the importer in 2014 for similar failures to conduct adequate due diligence (UNODC 2023: 50).

Enabling conditions for corruption

The corruption risks that threaten to undermine the EUDR are mostly systemic in nature, rather than linked to individual misconduct (Fripp et al. 2023; Wood et al. 2021; Transparency International 2024). Fragmented supply chains create opportunities because commodities pass through multiple intermediaries (traders, processors, cooperatives) before reaching exporters. In the Côte d'Ivoire’s cocoa sector, investigations found intermediaries had routinely mixed cocoa from protected forests with legal batches, with falsified origin certificates masking the true source (Mighty Earth 2017). Weak land registries characterised, for example, by complex procedures or lack of ownership transparency, create the opportunity for corrupt officials to issue multiple titles for the same plot or backdate documents to support fraudulent claims (UNODC 2023). Limited transparency, on the other hand, means that concession awards, licence renewals and inspection results are not publicly disclosed, making it difficult to detect irregularities and creating a false appearance of legality (UNODC 2023). Operators and traders may also find it difficult to meet due diligence requirements where supply chains are complex and opaque. For example, the absence of beneficial ownership registries in producer countries further obscures who profits from forest conversion, enabling politically connected elites to hide their interests behind shell companies (UNODC 2023).

These systemic vulnerabilities involve a diverse set of actors: state institutions (land registries, forestry agencies, customs) that control official data and enforcement; private sector actors (operators, traders, intermediaries) that manage supply chain information; and even civil society organisations that provide independent oversight. Corruption can occur within any actor group or through collusion between them, making multi-stakeholder accountability mechanisms essential.

EUDR vulnerabilities to corruption

Beyond corruption risks that may emerge along supply chains, some observers argue that the EUDR itself has arguably some design vulnerabilities that could affect its successful implementation by exposing the system to corruption.

Country benchmarking

The country benchmarking classification, released by the EC in May 2025, uses a methodology that critics argue focuses too narrowly on historical deforestation metrics and political sanctions, failing to sufficiently incorporate governance, legality and enforcement capacity. Critics argue that some countries with significant governance challenges have been classified as “low risk”, and products and commodities originating from these countries may not be required to have a full risk assessment or adopt mitigation measures, potentially creating blind spots (Canby and Walkins 2025; Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023: 305). A proposed addition of a “negligible risk” or “no risk” category, as part of the simplification measures, may further undermine the foundation of the EUDR due diligence system, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI 2024).

Reliance on domestic legality

As discussed previously, formal legality may not reflect actual integrity. The EUDR provides no clear mechanism for operators to distinguish between genuine legal compliance and formal compliance achieved through corruption. This creates a risk that operators and traders who rely on document checks will inadvertently accept products from corrupt sources (Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023).

Geolocation

The EUDR's traceability requirements depend on the integrity of geolocation data provided by suppliers. However, GPS coordinates can be easily falsified, and there are limited mechanisms to verify their accuracy. While satellite imagery can detect deforestation, it cannot definitively link cleared areas to specific shipments without reliable ground-truthing463b2ae83e23 (Wood et al. 2021: 29-30)

Furthermore, national cadastral systems in many producer countries are incomplete, outdated or vulnerable to manipulation. When operators cross-reference supplier coordinates with official land registries or forest concession maps, they may be checking their data against systems that are themselves corrupted. In such contexts, geolocation data may be technically accurate but still providing misleading information for due diligence (zu Ermgassen et al. 2024; UNODC 2023).

Overview

Table 1 represents the author’s synthesis of how the aforementioned forms of corruption and enabling interact across the EUDR’s three core requirements. A single illicit act (e.g. bribing officials to falsify land titles) can simultaneously compromise traceability (by obscuring true origin), legality (by creating false legal appearance) and due diligence (by providing fraudulent documentation that passes surface-level checks). These cascading effects highlight that countering corruption demands system-wide reforms rather than isolated fixes.

Table 1. Mapping EUDR corruption risks

|

Corruption / compliance risk |

Traceability risks |

Legality risks |

Due diligence risks |

Enabling / persistent conditions |

|

1. Tenure/permit irregularities |

Fraudulent or duplicate land titles obscure true origin of production; front companies may mask ownership. |

Land illegally allocated through patronage or corruption; permits later “regularised” to appear legal. |

Officials may accept bribes to validate forged tenure documents in due diligence checks. |

Weak land administration enables manipulation of titles and permits. |

|

2. Geolocation/data integrity risks |

Fake or imprecise geolocation data make farm boundaries unverifiable; allows product laundering. |

Illegal farms can be disguised as compliant by falsifying location data. |

Auditors unable to verify coordinates due to poor data systems or manipulated records. |

Lack of reliable cadastral data and technical capacity perpetuates unverifiable mapping. |

|

3. Document fraud at transport/export |

Fake transport permits or waybills obscure product origins in traceability systems. |

Illegal products gain legal appearance through forged export licences or customs clearances. |

Bribes or collusion allow falsified paperwork to pass as compliant documentation. |

Weak enforcement and systemic tolerance for document fraud maintained through corruption networks. |

|

4. Procedural compliance masking governance failure |

Over-reliance on documents encourages superficial traceability. |

Legal frameworks remain captured by elites; compliance serves formality rather than justice. |

Companies focus on box-ticking instead of investigating real governance risks. |

Institutional culture rewards procedural compliance over substantive governance reform. |

|

5. Political capture and beneficial ownership opacity |

Shell companies and nominee arrangements obscure true ownership, making supply chain mapping unreliable. |

Politically connected elites secure permits through influence, creating formally legal but corrupt concessions. |

Absence of beneficial ownership registries prevents operators from identifying conflicts of interest or elite capture. |

Lack of transparency requirements for ultimate beneficial owners enables covering of corrupt interests. |

|

6. Bribery and collusion in enforcement |

Payments to forestry officials allow illegal production in protected areas to go unreported, breaking chain of custody. |

Bribes to grading officials enable mis-classification of timber or agricultural products, making illegal products appear legal. |

Auditors and inspectors may be bribed to provide favourable reports, compromising independent verification. |

Low salaries for forest officials, remote working environments, and weak accountability mechanisms create strong incentives for corruption. |

Mitigation strategies and good practices

This section provides a list of mitigation measures that have the potential to help address the corruption risks detailed in the previous sections.

The measures discussed here draw on evidence backed strategies from the land sector and other forest-risk commodity contexts. The measures presented here are not exhaustive but prioritise practical interventions that directly support EUDR implementation in the short to medium term. However, it is important to note that while the EUDR can be strengthened to effectively counter corruption, addressing governance weaknesses beyond the EUDR may be necessary in the longer term, which requires working closely with production countries, the private sector and local communities.

Data integrity and verification

The EUDR offers an important opportunity to strengthen integrity across forest-risk commodity supply chains. For example, zu Ermgassen et al. (2024) recommend that the private sector and government authorities, supported by the EC, combine the mandatory plot-level coordinates with large-scale satellite imagery or sensing data that can capture complex dynamics such as indirect land use change in areas with a predominance of smallholder production. The use of mixed method technology has been used by the multinational Cargill in partnership with the WRI to produce a more reliable deforestation baseline in the soya bean supply chain used in Brazil and Paraguay, and palm and cocoa globally, according to Kroeger et al. (2021: 55). The public availability of spatial data and technology is constantly evolving and provides opportunities for enhancing transparency and the integrity of datasets (Fripp 2023: 49).

Ghana provides an example of how to integrate commodity and forest data within a single and coherent national system, through inter-agency collaboration. Ghanaian forests are used for multiple productions (timber, palm oil, cocoa and coffee), creating complex issues around land use and competing interests. The government decided to align different datasets instead of managing the sectors separately. The forestry commission and the Ghana cocoa board have been working closely to connect their respective monitoring systems: forest data through the national forest monitoring system and cocoa production data through wider sector initiatives. This joint approach is increasingly expanding beyond these two bodies to include land administration services responsible for cadastres, agencies that issue permits and institutions overseeing environmental impact assessments. By linking these datasets, Ghana is creating a more complete picture of who is using the land, for what purpose and with what environmental implications (Fripp et al. 2023: 82).

This integrated model allows forest and commodity data to be reconciled with land titles, farm boundaries, production records and compliance processes including the EUDR. As the system evolves, public access to key information is becoming a central feature, improving transparency for communities, companies and regulators. Fripp (2023: 82) argues that together these reforms are helping Ghana build a traceable, accountable and open framework for managing land use across its forest and agricultural landscapes.

Open data platforms that integrate information from multiple government agencies can reduce corruption risks by making inconsistencies visible. Ghana’s approach of linking forest, cocoa, land administration and environmental data illustrates how integrated systems make it harder to conceal illegal conversions or secure fraudulent permits (Fripp et al. 2023). Similarly, digital public infrastructure for traceability, such as the open-source system used for Honduras’ coffee exports, ensures that geolocation, production volumes and shipment information are recorded transparently and can be audited by multiple stakeholders. Making such platforms publicly accessible, while protecting commercially sensitive information, enables civil society and the media to play watchdog roles.

Risk assessment and benchmarking

Canby and Walkins (2025) argue that the EUDR would benefit from a broader view of what constitutes a risk by integrating governance quality and corruption indicators into the risk classification and benchmarking. Both the EU and companies can also integrate quantitative, objective and internationally recognised corruption data – such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index or the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment– into their risk assessment methodologies, regardless of a country’s official EUDR classification (Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023: 310). By integrating this kind of data, the EU and companies could add a more objective measures of institutional integrity to risk assessments. This strengthens risk detection, reduces false “low-risk” assumptions and ensures that due diligence reflects actual governance conditions, not just regulatory labels. Moreover, it counteracts the risk of inadequate or misleading EUDR country benchmarking that can create complacency among operators and traders.

Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps (2023: 295) argue that companies should analyse land use dynamics at multiple scales to understand systemic risks, including corruption in land allocation and permitting systems prevalent in the forestry sector. For example, property-level analyses can help identify proximate drivers of deforestation (e.g. cattle ranching, soya bean expansion), while jurisdictional analyses capture indirect drivers, such as the displacement of other land uses (Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023).

Enabling civil society and multi-stakeholder monitoring

Civil society organisations, local communities and Indigenous peoples play a critical role in detecting and exposing corruption in forest-risk commodity sectors. In Indonesia and Malaysia, local organisations have documented traceability failures, exposed fraudulent certification schemes and mapped ancestral lands to counter illegal concessions, but they were largely excluded from the EU-Indonesia-Malaysia EUDR task force established in 2023. Representatives from Indonesian civil society organisations noted that civil society has the capacity to collect field data and document violations, and that their experience and knowledge can benefit EUDR implementation (Human Rights Watch 2024).

Civil society monitoring serves multiple anti-corruption functions. First, independent monitoring can verify the accuracy of operator due diligence statements by cross-referencing geolocation data with ground observations, identifying discrepancies between reported and actual land use. Environmental groups in Malaysia, for instance, found that authorities systematically under-reported deforestation rates and civil society can address these data gaps (Human Rights Watch 2024). Second, community-based monitoring systems can detect illegal activities in remote areas where official oversight is limited or compromised. Indigenous organisations in different regions have been particularly effective at identifying encroachment on community lands and documenting human rights violations associated with commodity production. Third, investigative journalism and civil society research exposes high-level corruption that operators’ document reviews cannot detect, such as politically connected beneficial ownership or regulatory capture.ac4d987d8a49

Effective civil society participation depends on strong whistleblower protections and freedom of information laws; the skills and resources to gather and analyse data, such as training in satellite monitoring, legal frameworks and supply chain mapping. Formal mechanisms for participation are also important and include consultations with competent authorities, audits and grievance systems. The EUDR recognises this by requiring enforcement authorities to respond to well-founded concerns from civil society, creating an opportunity to build on this provision.

Multi-stakeholder initiatives that bring together governments, companies, civil society and affected communities offer promising models. In Argentina, the industry platform VISEC brought together these actors to develop national traceability and certification systems for soy and beef that meet both EUDR and local sustainability standards. Similarly, Honduras achieved EUDR compliance in its coffee sector through cooperation among local cooperatives, processors, exporters, and civil society partners to develop open-source digital infrastructure for plot-level traceability (Li et al. 2025). These collaborative approaches may help balance commercial interests with transparency and accountability, while ensuring that smallholders are not excluded from compliance processes or subjected to corrupt gatekeeping.

International and regional cooperation

One of the criticisms levelled at the EUDR is that it represents a unilateral measure designed by European authorities without adequately engaging producer country stakeholders (Besliu 2024). This approach undermines the regulation’s legitimacy and risks creating tensions that could weaken implementation.

However, existing international frameworks provide established mechanisms that the EUDR could leverage to strengthen cooperation and address corruption more systematically. The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), ratified by most producer countries, provides comprehensive provisions on prevention, criminalisation, international cooperation and asset recovery that are directly relevant to forest-sector corruption. Chapter IV establishes mechanisms for international cooperation including mutual legal assistance, extradition and asset recovery that could support enforcement of the EUDR’s legality requirements. By connecting compliance more explicitly with UNCAC obligations, the EUDR can create synergies between trade access and anti-corruption commitments.

Regional frameworks may offer additional points of leverage. The African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC) commits member states to transparency, accountability and elimination of corruption in public services. The African Union’s (AU) land governance strategy specifically addresses corruption in land administration and natural resource management, providing a policy framework that aligns with EUDR objectives (Transparency International 2024a). In Latin America, the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption establishes similar standards. By referencing these regional commitments, the EUDR could frame its requirements as supporting rather than imposing governance reforms, thereby reducing criticisms it has received that it amounts to a form of legal colonial intervention (see Besliu 2024; Garcia Da Silva and Milcamps 2023: 305).

Sectoral initiatives also demonstrate the value of international cooperation. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), implemented in 28 African countries, requires disclosure of beneficial ownership, contracts, revenues and licensing processes in the extractive sector. While focused on mining and oil, EITI methodologies for multi-stakeholder verification, public disclosure and corruption risk assessment offer tested approaches that could be adapted to forest-risk commodity sectors. Similarly, the FLEGT process, which the EUDR replaces, established voluntary partnership agreements (VPAs) between the EU and producer countries to jointly address illegal logging. Despite its limitations, the FLEGT partnership approach and focus on governance reforms provide potential lessons for EUDR implementation, particularly the importance of sustained technical assistance and capacity building. The case of Ghana discussed above is an example of how VPAs have encouraged positive reforms (Fripp et al. 2023).

Enhancing supply chain transparency

Supply chain transparency is fundamental to both EUDR compliance and anti-corruption efforts, and achieving it requires addressing the layers of opacity that enable corrupt practices. Three interventions can in particular reinforce transparency: beneficial ownership disclosure, open data platforms and the use international financial regulations.

Beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) is essential for exposing politically connected elites who profit from forest conversion through shell companies and nominee arrangements. Without clarity over who ultimately controls companies operating in forest-risk commodity sectors, neither operators conducting due diligence nor enforcement authorities can detect conflicts of interest, asset concealment or proceeds from corruption. However, the coverage of beneficial ownership across jurisdictions is patchy; for example, as of 2023, 23 of 54 African countries have laws requiring beneficial ownership disclosure, with Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and several others establishing central registers (Etter-Phoya et al. 2023). When publicly accessible and properly verified, these registers allow investigators to trace corporate ownership structures and identify red flags. In Nigeria, for example, tools linking beneficial ownership data to politically exposed persons revealed over 500 red flags in the extractive sector, with 75% of companies with irregular ownership structures concentrated in oil and gas (EITI n.d.).

Having beneficial ownership information available and requiring operators and traders to check and verify it could arguably strengthen the EUDR’s due diligence processes. This could reduce the scope for intermediaries to obscure ownership and help verify that suppliers are not controlled by officials with regulatory authority over the sector, a clear corruption risk. Producer countries, supported by international initiatives, such as the African Beneficial Ownership Transparency Network, EITI and Open Ownership, could establish or adapt beneficial ownership registers that cover forest-risk commodities.

International financial transparency mechanisms provide additional leverage. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards on anti-money laundering require countries to identify and verify beneficial owners and report suspicious transactions (UNODC 2023: 54). Forest-sector corruption often involves money laundering through timber exports, land transactions or commodity sales, making financial intelligence units potentially valuable partners in detecting irregularities. EITI members already commit to disclosing beneficial ownership, contracts, revenues and state participation in extractive sectors (Maslen 2025:23-24). These transparency standards could be extended to forest concessions and agricultural commodity agreements.

- Forest land management refers to how forest land resources, including plants, animals and water or soil, are overseen and used for the production of goods that satisfy human needs. This often involves trade-offs among stakeholders such as producers, owners and Indigenous communities (FAO 2014; UNODC 2023: 24)

- Illegal logging refers to unlawful tree cutting according to relevant national regulations, as well as any illegal actions along the wood supply chain, such as transport, processing or export, even when the wood was legally harvested (FAO 2014: 10).

- For more information, the reader is invited to consult the following sources: the EU has produced the implementing regulation (EU) 2025/1093 and commission guidance (2025) that specify the procedures for risk classification, due diligence data submission and verification protocols. The guidance document was updated in April 2025, and a step-by-step guide on how to implement the EUDR is also available on a dedicated portal. The World Resources Institute also provides a seven question summary of the EUDR that is a useful and clear introduction to the regulation. The European Forestry Institute has developed the Methodological Note: Developing a Legality Due Diligence Tool for EUDR Compliance.

- A polygon is a specific type of data that uses multiple coordinate pairs to define a closed area or boundary, often for larger or more complex plots. The EUDR advises using polygons for plots of land above four hectares to provide more details on the perimeter of each land plot.

- This requires operators and traders to either collect their own geolocation data – for example, through a custom-built GPS system – outsource the collection to a third-party provider or in some cases use monitoring tools developed by the EU such as earth observation data from the European Space Agency. The EUDR further envisions that EU authorities will verify geolocation data through inspections using satellite monitoring tools and in-situ analysis (EU Space Agency 2024).

- Transshipment is a logistics operation and refers to transferring goods from one mode of transport to another, while indirect export is when goods physically pass through a third country’s port or hub before reaching the final market.

- Ground truthing in cartography refers to confirming data collected at a distance by measurements made on location (GIS Geography n.d.).

- Examples of investigative journalists reporting on land corruption include: MacLean 2017; AlJazeera 2013; Sawadogo 2025.