Query

What are the biggest corruption issues in the national revenue administration in Tanzania? What are current integrity initiatives? Which measures have worked so far and which not? How do these compare to other countries’ tax administrations?

Background

Tax administration and corruption

Tax administration is the system by which government agencies implement and enforce tax regulation, including the identification and registration of taxpayers, processing of tax returns and third-party information, verification of tax returns, collection of taxes and the provision of services to taxpayers (Alink and van Kommer 2016:163). A tax authority is the government institution that is primarily responsible for overseeing these duties (Academy of Tax Law n.d.). Efficient tax administration provides a critical source of revenue for governments to finance public services and infrastructure development, thereby supporting effective economic development and social welfare (Salawu 2023).

However, due to the complexity of tax laws and the high discretionary powers of tax officials, tax administration is considered to be one of the areas of public administration most vulnerable to corruption (Morgner and Chêne 2014:2). The main opportunities for corruption in tax administration relate to collusion between tax officers and taxpayers (often resulting in tax evasionb16830036755), corruption by the tax official themselves, patronage networks, and international tax fraud and evasion schemes (Morgner and Chêne 2014:2). In addition, as well as using corrupt means to break the rules, undue influence by powerful interest groups can be a means of changing the rules, such as where vested interests use their clout to change tax codes to shift the tax burden onto other social groups or business rivals (Morgner and Chêne 2014:2).

The tax base in Tanzania in a regional perspective

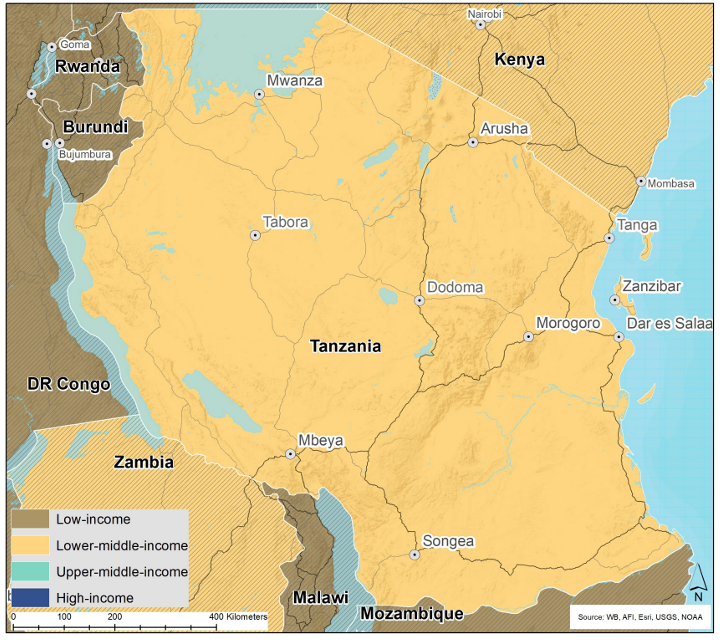

Tanzania ranks comparatively low for GDP, $1.28 thousand per capita as of 2025, at 31st place in Africa (ISS Futures 2025; IMF 2025). It is a lower-middle income country and as of 2023, its population was 66.6 million, with a life expectancy of 66.8 years (WHO n.d.). Despite rich mineral deposits the country scores poorly on various indices of basic infrastructure and almost 75% of people in Tanzania live below the poverty line (ISS Futures 2025).

Figure 1: Tanzania and neighbouring countries

Source: ISS Futures 2025

As such, effective tax collection in lower-middle income countries such as Tanzania is particularly important to finance public services such as health, education, infrastructure and security, and ultimately make progress towards the more equitable distribution of scarce economic resources.

Nonetheless, inefficiency in tax administration affects many low and middle-income countries, and Tanzania – where levels of voluntary tax compliance have historically been low – is no exception (Ng’eni 2016). The tax collection rate in Tanzania is slightly lower than some regional peers such as Burundi, but not significantly so (NAO 2025:21). In 2024, Tanzania’s tax revenue equated to 13% of GDP (World Bank 2025).

Table 1: Tax yield for East African countries for five years

|

Country |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 |

2023/24 |

|

Kenya |

13.70% |

15.00% |

14.20% |

13.8% |

|

Rwanda |

16.30% |

15.80% |

15.00% |

14.9% |

|

Tanzania |

11.70% |

12.80% |

12.50% |

13.0% |

|

Uganda |

13.00% |

13.50% |

13.70% |

13.5% |

|

Burundi |

17.00% |

17.60% |

18.00% |

17.0% |

Source: NAO 2025:21.

Crucially, a tax-to-GDP ratio of 15% has been identified as a ‘tipping point’ associated with an acceleration in the rate of economic growth and development (Choudhary, Ruch and Skrok 2024), suggesting that further reforms to enhance the effectiveness of revenue collection could generate positive spill-over effects. The National Development Vision established the target that by 2025, tax revenue should account for 20% of GDP, though it seems improbable this target will be met (Shirima 2021: 135).

In a wider context, African countries have inherited tax systems from former colonial powers that continue to exercise considerable influence on international tax frameworks (Etter-Phoya and Mukumba 2021). Many of the tax treaties that African countries inherited are based on past priorities from as far back as 60 years, which were often based on unequal bargaining power (Hearson 2015). This has led some to be vulnerable to unnecessary revenue loss, as past governments had negotiated away taxing rights for which they now get no concessions in return (Hearson 2015:34).

According to Etter-Phoya and Mukumba (2021) this, by design, has embedded inequality within the international tax regime with regards to complex rules around transfer pricing, intellectual property, shell companies and offshore financial centres. In practice, multinational companies continue to pursue aggressive tax avoidance and tax evasion strategies in African countries, including through profit shifting (African Union Commission 2015: 24). In the early twenty-first century, Tanzania reformed its investment and tax laws in an effort to attract foreign direct investment by providing a range of incentives to multinational companies, including ‘the ability to repatriate 100% of profit, capital allowance and ability to carry forward tax losses to [offset] future liabilities’ (Shirima 2021:140).

The Tanzania Revenue Authority

The Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA) is a semi-autonomous revenue authority (SARA), founded in 1996 by Act of Parliament No. 11 of 1995 to oversee tax administration in the country (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:427. TRA n.d.). The TRA manages four core departments: customs and excise, domestic revenue, large taxpayers and tax investigations (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:427). The Zanzibar Revenue Authority (ZRA) is responsible for revenue administration in Zanzibar; however, this Helpdesk Answer will focus only on the TRA and on the national tax system and tax administration in mainland Tanzania.

The TRA is mandated to collect, assess and account for tax revenue for the central government. Although the country’s tax base remains relatively small, the TRA is tasked with collecting many different types of taxes, including value added tax (VAT), digital service tax, stamp duty, corporation tax, capital gains tax, pay-as-you-earn (PAYE), income tax, withholding tax and gaming tax, as well as various customs taxes and a wide range of other levies.42ec740e9a50 The processes for administering tax are set out on the TRA’s website (TRA 2025).

As a SARA, the TRA has, in principle, has a more autonomous status than traditional revenue authorities (Jeppesen 2022). SARAs were established under the assumption that a more autonomous agency would be subject to less political interference through their autonomy (Jeppesen 2022). However, the board of directors is appointed by the minister of finance, and the commissioner general is appointed by the president, so the TRA’s independence may be limited (Kiunsi 2021: 64).

According to Tanzanian academics, in the past few years, the TRA has made efforts to modernise the country’s tax administration through initiatives such as the electronic fiscal devices programme, which was intended to improve VAT compliance (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:427).16d348d7b7ac Other policy changes have been enacted as part of an attempt to increase the TRA’s effectiveness, including the Tax Administration Act (2015), which consolidated all provisions related to tax administration to streamline the enforcement of tax laws by the TRA4f89f59cd2a5 (Shirima 2021:136). Research suggests that recent governance reforms in the TRA have been relatively effective and contributed positively to the process of state-building (Kim & Kim 2018:35).

Indeed, there have been indicators of improved performance, with the number of TRA staff rising from 4,749 in 2021 to 6,989 in 2025 (TRA 2025b). Over the same period, the TRA (2025b) has reported an increase in revenue collection of 78%. However, as the TRA does not publish annual reports, there is a lack of data that makes it difficult to determine the extent to which the increased tax revenue is attributable to the country’s recent economic growth or improved tax collection measures.

Nonetheless, the TRA faces several challenges, including balancing efficient tax collection with maintaining a business-friendly environment (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:427). Moreover, despite the progress made, Semboja et al. (2023: 42) have estimated that the TRA collects only 47% of the country’s tax revenue potential, suggesting that steps can be taken to further improve the agency’s effectiveness.

Corruption has historically been cited as a problem in the TRA (Fjeldstad 2003). Corruption in tax administration undermines public trust – the foundation of tax compliance (Kiunsi 2021: 70). Moreover, Tanzania forms part of the so-called ‘southern route’ for smuggling illicit goods such as drugs and counterfeit goods to Europe (Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime 2019). Informal cross-border trade (ICBT) is common in the region, amounting to 42% of all trade (Charles 2023: 2). Tanzania’s porous borders with the high-conflict countries of Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) also make it vulnerable to organised crime. Organised crime in the region drives corruption in Tanzania in general and high levels of customs violations in particular (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

This Helpdesk Answer examines the key drivers and forms of corruption that affect tax administration in Tanzania under the TRA, particularly those that impact the effectiveness of the TRA as an institution. It considers wider contextual factors that help or hinder tax administration and the implications these have on the country. Finally, it looks at the integrity measures that the TRA has enacted to reduce corruption and related offences, as well as recommended measures that have been proposed by analysts and practitioners.

Corruption risks in Tanzania’s tax administration

Drivers of corruption in tax administration

The literature suggests that there are several core drivers of corruption in tax administration in Tanzania, which include a complex tax system, overseen by an institution with a monopoly over decision-making, relying on a legal framework that enables opacity. The TRA’s capacity constraints, a large informal economy and social norms that encourage non-payment of taxes by citizens prevent effective tax administration and may contribute to corruption in the agency. Furthermore, Tanzania’s geopolitical environment can exacerbate corruption risks given the instability and organised crime networks operating in the wider region (ENACT Africa 2023).

Complex international tax rules

The international tax system has complicated rules for multinational corporations about tax payable in different jurisdictions. The complexity of this system, together with low enforcement capacity in many African tax administrations, enables aggressive tax avoidance by multinational companies (Etter-Phoya & Mukumba 2021; Shirima 2021). Trade mispricing, base erosion and profit shifting are tax avoidance strategies used by multinational corporations to exploit grey areas in international tax frameworks, effectively shifting profits from the countries where they are earned to low tax jurisdictions.

African tax administrations often lack sufficient lawyers, forensic accountants and investigators to match multinationals in negotiations about transfer pricing and asset valuations (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa 2015: 31). Profit shifting is sometimes facilitated by bribery – yet this type of offence is ‘virtually undetectable, hard to sanction and as a result can be found even in the tax administration in highly developed countries’ (Bilicka & Seidel 2020).

Tax rules and procedures for small to medium-sized enterprises in Tanzania are also complex in relation to the size of the economy (Kyomo and Buhumila 2025:430). Complicated tax rules, together with inefficient enforcement processes and a lack of transparency, reportedly reduce trust among the public in the fairness of the tax system (Kyomo & Buhumila 2025: 426-427).

As of early 2025, businesspeople at a meeting between the Confederation of Tanzanian Industries and the TRA on tax administrative practices were complaining that tax assessments often exceeded their actual earnings, resulting in job losses and the closure of some factories (Mwendapole 2025).

Extensive discretion by TRA officers when enforcing tax regulations

Enforcement of tax law is primarily conducted by the TRA, but law-enforcement agents – who are not themselves tax specialists – may also be involved when there is a need to assist enforcement actions (Kiunsi 2021: 68-69).

Shirima (2021:134) states that the tax legal regime grants TRA officers widespread powers, including to access taxpayers’ bank accounts even without a court decree, to sell assets and close businesses to recover tax liability and to collect taxes through the use of third parties. These discretionary powers are not limited to TRA agents; Shirima (2021:135) states that under section 10 of the 2004 Income Tax Act, the minister of finance has the right to exempt certain classes of firms from tax liabilities, simply through publishing this decision in the government gazette. These wide-ranging discretionary powers of tax officials and the minister of finance in Tanzania have, according to Shirima (2021:140-1), created opportunities for undue influence and corrupt behaviour.

To study the TRA’s enforcement and due processes, Komba (2025) conducted interviews with tax practitioners in law firms, tax accounting firms, members of the tax appeals board and members of the revenue appeals tribunal. The study found that the TRA has extensive discretionary power over taxpayers and that its tax enforcement powers are often extra-judicial as they do not entail the oversight of judicial organs (Komba 2025:69). Indeed, if a taxpayer wishes to appeal against a tax assessment issued to them, the 2015 Tax Administration Act stipulates that this appeal must be lodged with the commissioner general of the TRA rather than with a neutral third-party arbiter or court (Shirima 2021:137).

While extensive powers are useful for the agency, they can create a risk of abuse by TRA officers that can lead to taxpayers being wrongly deprived of their assets and having to cover high costs related to litigation (Komba 2025:72). Komba (2025) describes the due process in the collection and enforcement of taxes as being undermined by tax officials who do not observe professional integrity and violate taxpayers’ rights during the process. For example, there was a reported instance of a taxpayer challenging the collection of tax as no tax assessment was issued, to which the commissioner general refused to refund the money (Komba 2025:72).

At the same time, legal penalties for tax avoidance are low, with the chief provision simply being that the TRA commissioner general has the power ‘to adjust a person’s tax liability as appropriate to counteract any tax avoidance […] that may result because of a transaction aimed at tax avoidance’ (Shirima 2021:140). As such, it appears there is little criminal liability for tax offences. In Shirima’s (2021:143) view, the low risk of detection and punishment for tax evasion incentivises taxpayers to seek to collude with tax officials to reduce their tax liability, including through the payment of bribes.

The pattern of combining force, corruption and tax enforcement was found in Kiunsi’s (2021:69-70) study of interactions between tax officials and small businesses. Malpractices by staff at the TRA were alleged in interviews with business owners, which reportedly led to a hostile relationship between taxpayers and tax collectors and seemed to result in a negative view of the wider government (Kiunsi 2021:70). Dissatisfaction with the integrity of the TRA has reportedly led to a growing number of potential taxpayers transforming their businesses into small ventures with limited capital of 4 million Tanzanian shillings to qualify for informal sector identity cards and therefore avoid interaction with tax officers (Kiunsi 2021:70). As such, the government loses revenue due to tax avoidance.

The informal economy

Tanzania’s informal economy is comparatively large. In 2023, it accounted for approximately 45% of the country’s GDP, thereby imposing considerable constraints on economic growth, and second only to Zimbabwe in Africa (ISS Futures 2025). In 2020, it was estimated to account for 92.2% of employment in Tanzania (Thonstad 2025:11). This shadow economy creates challenges for tax collection, which relies on documentation and formalisation (Epaphra 2015: 2; Msafiri and Semboja 2022). The informal sector operates largely ‘outside the reach’ of the TRA, despite recent attempts to focus on finding more effective ways to tax the informal sector. One tax official stated that: ‘The informal sector holds immense potential, but mistrust and fear of penalties keep them from registering’ (Kyomo & Buhumila 2025: 430).

A large portion of Tanzania’s income is based on subsistence agriculture, which is also difficult to tax (Epaphra 2015:8; Msafiri and Semboja 2022). Moreover, the formal sector (comprising of large-scale farms, minerals and some manufacturing enterprises) buys from the informal sector, which further inhibits tax collection (Epaphra 2015:8).

The informal economy consists of unregulated and sometimes unlawful trade within Tanzania and across its borders. Informal cross-border trade (ICBT) is common, amounting to 42% of trade in the region (Charles 2023: 2). It is also facilitated by the so-call ‘Zanzibar route’, whereby the regulations of some products provide rent-seeking opportunities as the import duty imported to Zanzibar is lower than that of mainland Tanzania (Andreoni, Mushi and Therkildsen 2020:23). The large transaction costs associated with cross-border trade drive informal and illicit behaviour to avoid these costs (Charles 2023: 1). With so few border posts and banks, states often have no alternative but to ‘turn a blind eye’ to the practice (Charles 2023: 5).

ICBT is resilient to formalisation because it ensures financial survival for people living on the margins, including women (Charles 2023: 2). Corruption is common, and traders are subject to demands for bribes by police and border officials, particularly on the borders with the DRC and Burundi (Charles 2023: 16). Women are especially subjected to sextortion (Charles 2023: 6). Illicit cross-border trade is described by Charles (2023:5) as an ‘embedded social system’ in Tanzania.

The extractive industries

The extractive industries are particularly prone to corruption. The OECD (2016: 9) estimates that one in five cases of transnational bribery worldwide occur in the extractive sector. High politicisation and discretionary power in decision-making processes in the sector, particularly when combined with inadequate governance, can result in favouritism, clientelism, political capture, conflicts of interest, bribery and other forms of corruption (OECD 2016:18).

Tanzania has a large variety of natural resources, ranging from oil and gas to gemstones, coal, iron ore, nickel, gold and silver (TIC n.d.). While there is the potential that these resources could positively contribute to the development of the country, the Policy Forum (2025a:4) notes that resources including gold, diamonds and natural gas are particularly vulnerable to illicit financial flows, meaning their profits are often illegally shifted across borders. The Global Organised Crime Index (2023:4) points to the government’s establishment of mineral trading hubs to better oversee the trade in minerals as part of an effort to reduce smuggling and tax evasion, though it notes that opacity in the sector makes it difficult to determine the success of this initiative.

The transparency and accountability of multinational companies operating in the Tanzanian mining sector is an area of concern (Shirima 2021:139). Tax and royalty policies related to large-scale operations led to multinational corporations profiting from natural resources while making limited contributions to the Tanzanian exchequer (Shirma 2021:139). Scandals in the mining sector have included the 2017 ban for gold and copper concentrates, after the government initiated investigations of fraud and tax evasion by Acacia Mining (Roder 2019:3). This led to the responsible Minister of Energy and Minerals to resign and the Tanzania Mineral Audit Agency to be dissolved over collusion with multinationals and an ‘economic war’ against Acacia Mining, resulting in increased resource nationalism in the country (Roder 2019:3).

Recent analysis of the tax regime for mining companies in Tanzania by Scurfield (2023: 2) notes Tanzania’s ‘innovative approach […] based on an “equitable sharing principle”’ according to which deals are negotiated between the government and mining firms on a case-by-case case that set out how ‘economic benefits’ are to be split. While Scurfield (2023: 1) observes that there is limited transparency in the sector, despite laws requiring the government to disclose the terms of deals struck with mining companies, details about most of the contracts have not been publicly disclosed. Scurfield (2023: 1) states that the practice of negotiating profit-sharing ‘on a project-by-project basis, without any legal guardrails […] increases the risks of corruption and unfavourable deal terms’. In his view, the current approach increases tax avoidance risks, engenders opacity and reduces public trust that revenues from the sector are apportioned fairly (Scurfield 2023: 8).

Finally, corruption in the forestry system is reportedly pervasive, with bribes often paid to forest officials or local police officers to gain their support for illegal logging (Global Organised Crime Index 2023:3). According to the Global Organised Crime Index (2023:3), the introduction of a digital timber tracking system has doubled the size of royalties collected from logging, indicating some success in addressing the black market for timber. High-ranking police and local government officials have also been arrested for their involvement in the illicit economy and illicit trade, but there have been few convictions (Global Organised Crime Index 2023:4).

Social factors

Taxpayers often consider social factors related to tax payment and the potential benefits in return (Bräutigam 2008 cited in Kim and Kim 2018:40). Taxpaying is often driven by these social norms: peoples’ beliefs about what ‘others whose opinion matters to them would do and think they should do in this situation’ (Scharbatke-Church 2025). Research by Fjeldstad et al. (2020:10) finds that tax compliance in Tanzania is strongly associated with the customer’s perception of detection and punishment risks, alongside the businessperson’s perception of other businesses’ compliance behaviour. Taxpayers’ trust and perception of the tax administration (whether it is working beneficially for the common good) is another important social driver for tax compliance (UNDP 2024:135). Studies have found that countries with higher voluntary compliance are positively correlated with national identity, trust in the tax authority and perceived fairness in how the government treats the survey respondents’ own ethnic group (UNDP 2024:136).

In contexts where receipts are rarely issued for everyday transactions and tax returns are seldom filed for small businesses, citizens may make a rational choice to save money by evading tax. Since the TRA’s enforcement capacity is low, they may expect that this tax evasion will not be punished. A recent survey demonstrates that businesspeople in Tanzania believe that over 50% of other businesses are evading taxes (Asri et al. 2025: 4); 63% of Tanzanian businesspeople believe that tax evasion is justified if levels of public service delivery by government are unsatisfactory (Asri et al. 2025: 11).

Tanzania also relied heavily on foreign assistance for its state-building efforts, rather than relying on its own domestic tax base to mobilise resources (Kim and Kim 2018:42). While its dependency on foreign aid has declined over recent years, official development assistance still represents roughly 5% of GDP, which is just over a quarter of the government budget (Bourguignon and Platteau 2023:114). For taxpayers to be confident in the system, they must perceive that there will be a positive outcome from their payments, such as being used productively to fund fixed capital formation and social services (Kim and Kim 2018:40). Kim and Kim (2018) contend that extensive foreign assistance and tax exemptions has resulted in a low tax morale and tolerance for tax evasion and avoidance. Kim and Kim (2018:42) argue that the state-building process in Tanzania has not contributed to an implicit fiscal contract between taxpayers and the government.

Regional instability and organised crime

While tax crimes and corruption are usually viewed as distinct and separate crimes, they are often intimately linked, as Grasso and Ring (2023: 6) put it, corruption ‘greases the wheels’ of organised crime and tax crimes (Grasso & Ring 2023: 6).

Tanzania is exposed to regional organised crime, which takes advantage of flawed institutional structures, including courts and law enforcement (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). Most organised crime in and around the country involves illicit trade routes and requires cross-border smuggling, which often entails corruption to facilitate it (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

Tanzania’s neighbouring states Mozambique, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have a history of conflict. Most of these neighbours are currently enduring some form of violence, including insurgencies and civil war. Despite Tanzania’s historical political stability, it is vulnerable to the effects of instability in the wider region (ISS Futures 2023). Regional instability drives transnational organised crime networks across East Africa, including in Tanzania (ENACT Africa 2023). Tanzania’s long coastline is likewise attractive to organised crime (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). As such, Tanzania is a transit route for various types of trafficking, including arms, drugs and human trafficking (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

There is anecdotal evidence that Tanzania’s customs officials are tolerant or involved with trafficking activity (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).The smuggling of counterfeit goods is also a particular area of concern for Tanzania, with more than half of all goods imported into the country estimated to be counterfeit, including ‘pharmaceutical products, foods, construction materials, clothes, electronics, auto spare parts and tools’ (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). In 2025, industrialists and traders raised concerns to the TRA over the growing problem in Tanzania, noting that counterfeit goods were flooding the market through illegal border crossings (Mwendapole 2025). Smugglers frequently evade taxes on excise goods such as cigarettes and alcohol, which should net the TRA substantially more than they currently do. More than 50% of beer sold in Tanzania is sourced from the illicit alcohol trade (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

Financial secrecy

Tanzania, like most countries, provides for the incorporation of companies. While necessary for business, there are several structural factors that can provide opportunities to create multiple corporate layers of financial secrecy behind which individuals can conceal their ill-gotten gains. While Tanzania has a legal framework (the Companies Regulations – 2023) to facilitate some level of beneficial ownership transparency to mitigate these risks, there are obstacles to the implementation of this framework (Global Financial Integrity 2025). The obstacles cited by Global Financial Integrity (2025:19) relate to loopholes in the legislation, inadequate enforcement mechanisms for regulatory agencies and a lack of international coordination as many beneficial owners may live in one nation but have assets in another.

Moreover, while Tanzania has recently been removed from the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) grey list in June 2025, strategic deficiencies in its investigations and prosecutions for money laundering were consistently identified by the international body since October 2022, leading to its placement on the grey list for over two years (FATF 2025). Financial secrecy complicates effective tax administration by restricting financial information, making it difficult to assess tax liabilities and enforce compliance (Esteban and Barreix n.d.). While there is little documented information on the impact of financial secrecy on the tax administration in Tanzania, it is possible that this hinders the effectiveness of the TRA and opens up opportunities for corruption.

Forms of corruption in Tanzania’s tax administration

Administrative corruption

Administrative corruption consists primarily of bribery or embezzlement, which, while typically involving small amounts, collectively have a high economic cost and cause extensive social harm (Barrington et al. 2024: 247).

There are many connections between administrative corruption and tax crimes (Grasso & Ring 2023: 1-2; Turksen et al. 2023). Evidence suggests that officials from the TRA operate within complex networks including intermediaries to facilitate the bypassing of inefficient bureaucratic hurdles, often with informal payments involved (Basel Governance 2021). This can also include collusive conduct such as small traders paying bribes to avoid expensive licensing fees or businesses bribing a tax official to escape company tax. Before reforms starting in the late 1990s, such as the introduction of value added tax and the establishment of the TRA as a semi-autonomous agency, the revenue department within the Ministry of Finance in Tanzania was reportedly nicknamed ‘the tax exemption department’ in the early 1990s due to its widespread practice of granting tax exemptions to businesses that were willing to pay for this service (Shirima 2021:131).

There have also been instances of coercive corruption. In 2020, during the case of Proches Christian Kavishe v the Republic, an employee of the TRA was charged and convicted of corruption (Shirima 2021:141). The TRA employee, alongside two police officers, demanded a bribe from two businessmen who were travelling with their merchandise from Nairobi through the border to Mwanza (Shirima 2021:141). The businessmen refused to pay the bribe but were held up with their merchandise until they decided to pay.

Shirima (2021:133) states that, according to reports made by small businesses such as hotels and restaurants, tax officials in Tanzania have used taxpayers’ poor knowledge of tax legislation to extort them, making them pay more than they are required to. While Shirima does not state explicitly whether tax officials are personally pocketing these extra payments or simply cajoling taxpayers into paying more taxation, the implication is that this is a form rent-seeking for private gain on the part of individual TRA officers.

Cross-border corruption

One of the forms of corruption in Tanzania identified by Epaphra (2015:4, 6, 18) is customs offences,efa94d6f7c33 including smuggling and trade misinvoicing. Trade misinvoicing comprises several practices where customs information is misreported or manipulated to achieve different objectives, such as transfer pricing, bypassing import duties or export bans, smuggling and dumping (Andreoni and Tasciotti 2019:13). It can lead to either over-invoicing or under-invoicing, depending on the aims and results in a reduction in tax revenue. While not all trade misinvoicing involves corruption, many cases may involve collusion between private individuals on one hand and customs agents or tax officials on the other.

By analysing trade data, Andreoni and Tasciotti (2019) found that between 2013 and 2017, the cumulative value of trade underreporting in Tanzania amounted to over US$10 billion. The authors note that in Tanzania, the management of trade and tariff schedules provide opportunities for rent-seeking behaviour. They contend that trade misinvoicing and related forms of corruption serve as ‘key channels’ to allocate rents across influential networks across both the public and private sectors (Andreoni and Tasciotti 2019:12). Evidence suggests that, historically, the underreporting of trade in Tanzania points to corruption practices within the country’s internal tax administration (Fjeldstad and Rakner 2003 cited in Andreoni and Tasciotti 2019:9).

The authors cite structural reasons for trade misinvoicing, such as the fact that customs officials are undertrained and there is a high demand for corruption (Andreoni and Tasciotti 2019:14). In addition, profits from trade misinvoicing are also funnelled into politics through patron-client networks, which poses additional challenges to implementing anti-corruption reforms in customs and tax administration. This is because, according to Andreoni and Tasciotti (2019:14), revenue and port authorities in Tanzania are contested by political factions seeking to capture the large rents managed by these agencies. As such, they have few incentives to introduce reforms that would curb the illicit profits generated by trade misinvoicing.

Furthermore, low enforcement capacity in African tax administrations has enabled aggressive tax avoidance by multinationals (Etter-Phoya & Mukumba 2021). Corporate tax abuse, in the form of base erosion and profit shifting, forms the majority of illicit financial flows from Africa (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa 2015: 79). A significant contributor to illicit financial flows from Tanzania appears to be tax evasion from the undervaluation of imported goods (Epaphra 2015: 5).

Regulatory capture

Regulatory capture refers to ‘the result or process by which regulation, in law or application, is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest towards the interests of the regulated industry, by the intent and action of the industry itself’ (Carpenter and Moss 2013:13). These practices are common in the customs and tax sector, not least as ineffective tax collection primarily benefits multinationals and high net-worth individuals (UNCTAD 2025).

Since influential businesspeople can have an interest in weak tax authorities, they may attempt to influence politicians to change tax policies and practices. To give one example, Andreoni and Tasciotti (2019:14) observe that importers involved in trade misinvoicing have strong incentives to use part of the rents they accumulate to ‘corrupt the authorities involved in designing trade schedules […] and in implementing and enforcing import duties’. In these ways undue influence and corruption can reduce tax intake and facilitate tax avoidance (Grasso & Ring 2023; Turksen et al. 2023; UNECA 2015: 69).

There are indications that private interests – specifically, private sector entities subject to taxation by the TRA – have successfully influenced policy decisions to advance their own interests. Fjeldstad and Rakner (2024) argue that private companies are key sources of campaign financing and thus exercise considerable influence over elections in Tanzania, which can later translate to favourable treatment regarding tax policy and policy application.

For instance, the VAT act that was introduced in Tanzania in 1997 allowed for few exemptions and the zero-rating of only a limited range of products. It was therefore expected to broaden the revenue base, leading to increased tax revenue (Fjeldstad and Rakner 2024:129). However, the private sector mobilised to oppose the bill, by lobbing the parliament and the Ministry of Finance, pushing for their own special interests. The lobbyists employed the services of tax consultants to do so, most notably the former deputy commissioner general of the TRA (Fjeldstad and Rakner 2024:130). A revised VAT act signed in 2015 reintroduced many exemptions that had been originally abolished, as well as granting the Ministry of Finance discretionary power to issue further exemptions.

Grand corruption

Grand corruption is defined by Barrington et al. (2024:153) as ‘the abuse of high-level entrusted power usually with significant impact and potentially large private gain’. Grand corruption usually involves senior officials and extensive resources and causes deep damage to institutions and societies, and there have been some cases that indicate that this may be a problem in the tax administration sector of Tanzania.

In 2015, Tanzanian authorities suspended the head of the TRA as a result of a corruption probe, after the prime minister visited the main port of Dar es Salaam and found that 349 shipping containers that were listed as having arrived in the port were nowhere to be found (Reuters 2015). Other senior officials in the TRA were also suspended. Additionally, in 2020, two Chinese nationals were convicted of offering a US$5,000 bribe to the commissioner general of the TRA to evade company tax (The Citizen 2020). However, there is no information in the public domain to indicate that this offer was accepted by the commissioner, nor whether the head of the TRA was actively involved in the corrupt networks case.

State capture is a ‘type of systematic corruption whereby narrow interest groups take control of the institutions and processes through which public policy is made, directing public policy away from the public interest and instead shaping it to serve their own interests’ (Barrington et al. 2024: 298).

Direct evidence of state capture of the TRA is scarce. However, there have been some practices in Tanzania that indicate instances of interference by the executive branch in the administrative functioning of the TRA, including frequent dismissals of the commissioner by a previous president (Kiunsi 2021: 64-65). There have also been unclear directives from the executive about tax dispute resolution, indicating a pattern of the executive overreaching their authority into the realm of tax administration (Kiunsi 2021: 64-65). Shirima (2021:136,142) concurs, arguing that political intervention is a risk in tax administration in Tanzania; given that the ruling party effectively dominates the parliament and is able to pass legislation at will, the minister of finance has the ability to establish new tax laws ‘that suit the needs of the ruling elite class’. The Policy Forum (2025b) has observed that political considerations, such as the design to maintain electoral support, has occasionally led to the selective enforcement of tax regulations.

Similarly, while there is no public information about high-level penetration of the TRA by organised criminal groups, there are some clear risk factors. A study of the illicit narcotics trade along the eastern African seaboard posits that the regional criminal market requires more than bribery of low-level customs officials to operate (Haysom, Gastrow & Shaw 2018). The authors argue that, across East Africa, the trade relies on political protection by senior officials ‘who exert control over ports, customs and law-enforcement agencies’ (Haysom, Gastrow & Shaw 2018:1). They note, however, attempts by the Tanzanian central government to crack down on corruption and illegal drugs in the country’s ports around 2017 partly succeeded in disrupting criminal markets (Haysom, Gastrow & Shaw 2018:19-23).

State capture in the South African Revenue Service

Evidence of state capture is available in the case of the South African Revenue Service (SARS). This is a rare example of judicial findings about interconnections between grand corruption and tax crimes and is relevant to other tax administrations.

In 2018, a judicial commission of inquiry into SARS found evidence that President Jacob Zuma had colluded with multinational management consulting firm Bain and the SARS chief commissioner to dismantle a previously effective tax authority. Together, Bain and the commissioner embarked on a ‘premeditated offensive’ against the tax authority in ways that benefitted both parties in ‘symbiotic’ ways: Bain received a large state contract; the commissioner consolidated his personal power at the institution (SARS Commission 2018: 27). They restructured the institution, eliminating successful units such as the large business centre, compliance unit and integrity unit, removing oversight mechanisms over settlements, and triggering the exit of experienced senior managers (SARS Commission 2018: 42-57).

The commission found that capture by private interests (both legitimate and illicit businesses) destroyed institutional and human capacity at the formerly effective institution in ways that would be difficult for it to recover (SARS Commission 2018: 2-47). One result of this conduct was a loss of tax revenue; but the commission concluded that an even more serious impact was the decimation of human capacity and governance at the institution (SARS Commission 2018: 57-58).

The impact of corruption in Tanzania’s tax administration

Estimates2624676c3f67 suggest that Tanzania should be collecting approximately double the tax revenue it currently does: Semboja et al. (2023: 42) calculate that the tax collection rate is only 47% of the country’s tax revenue potential. Tax Justice Network (2024) estimates that, as of 2024, the country loses US$124 million to global tax abuse, which is equivalent to 14.03% of the health budget and 5.92% of education spending. This directly reduces the ability of the state to invest in key social sectors.

While corrupt practices by no means account for all of this missing tax revenue, corruption in tax administration can reduce revenue collection rate in two main ways. First, corruption undermines voluntary tax compliance. Legitimacy and trust in public institutions are the foundation of voluntary tax compliance – citizens’ perceptions of whether a tax authority is trustworthy significantly affect levels of compliance and overall revenue collection (Chindengwike & Kira 2021: 2). An IMF study found that 1% increase in the share of citizens’ perception of little or no trust in the tax department leads to a 0.22% decrease in VAT tax efficiency (Yamou, Thomas & Cai 2024:2).

Second, corruption weakens the institutional capacity of tax administrations to enforce anti-avoidance measures (Ismail & Richards 2023:1; Policy Forum 2025a). This was highlighted in a recent study of Nigeria, in which researchers demonstrated a link between profit shifting by multinationals and the erosion of capacity at the tax administration. The authors found that the effect of profit shifting in reducing tax administration capacity was greater when corruption was part of the illicit behaviour (Gabanatlhong et al. 2024: 5).

Research shows that, in the past, perceived corruption at the TRA had a negative effect on tax compliance (Kim & Kim 2018:57). Encouragingly, the picture from Afrobarometer survey data is one of general improvement over the past decade in levels of trust in the TRA and perceived corruption, with a slight decline from 2022 to 2024.

Table 2: Afrobarometer data on Tanzanians’ trust in and perceptions of corruption on the part of TRA officials

|

2012 |

2015 |

2022 |

2024 |

|

|

Percentage of those surveyed who stated that ‘most’ or ‘all’ tax officials are involved in corruption |

38 |

14 |

12.4 |

16.7 |

|

Percentage of those surveyed who stated that they trust the TRA ‘somewhat’ or ‘a lot’ |

N/A |

38 |

72.4 |

66.6 |

Source: Afrobarometer (2015, 2017, 2023, 2025).

Conceivably, the slight decline recorded from 2022 to 2024 is related to the protests that broke out in 2023 and 2024 as a result of tax related grievances among traders and allegations of corrupt practices by TRA staff. In 2023 a strike took place in markets in Dar es Salaam during which shop owners shuttered their businesses in protest (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:426). A key issue included the alleged indiscriminate seizure of goods by TRA officers under the pretext of value verification, which was viewed by affected businesspeople as a means of extorting illicit payments in exchange for not seizing goods, particularly during the import process (The Chanzo Reporter 2023). Other grievances pertained to the TRA’s inability to distinguish between street vendors and legitimate traders, the freezing of traders’ bank accounts, introduction of a new VAT return system perceived as unfair, and the complexity and difficulty in understanding these tax laws (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:426). Within a few days, the strike had spread nationwide, and ten foreign envoys sent a joint letter to the Tanzanian government stating that many investors were experiencing significant disruptions due to the TRA demanding payments and account reconciliations dating back 15 years, and that the TRA was refusing to recognise tax concession agreements that had previously been put into place (Kyomo and Buhimila 2025:426). Similar protests also took place in 2024 (Mosenda 2024). These incidents, Kyomo and Buhimila (2025) note, underscore the need for the TRA to put into place a more predictable and transparent tax administration system.

Integrity measures

National initiatives

The Tanzanian government’s anti-corruption initiatives are set out in its national anti-corruption strategies. This has included phases I to III and now is implementing the National Anti-Corruption Strategy and Action Plan Phase IV (2023-2030) (President’s Office 2023). This current phase increases focus on empowering civil society to participate in anti-corruption initiatives, enhanced transparency in state institutions, enhanced ICT-based systems in public service delivery and strengthening integrity in the electoral processes (President’s Office 2023).

The Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau (PCCB), which is an independent anti-corruption body, reported that it had monitored over 1700 development projects to tackle corruption risks in sectors such as infrastructure, health and local government financial management (Maricha 2025). It also recently focused on improving tax collection, to help address gaps in tax systems where local councils had failed to remit withholding taxes in full (Maricha 2025). The PCCB additionally conducts surveys across rural and urban households in Tanzania on the perceptions and experiences of public officials on corruption in the country.

Regional initiatives

There have been regional level initiatives focused on improving integrity mechanisms in tax authorities, premised on the notion that organisational level reforms will be ‘pivotal’ in ‘mitigating corruption risks’ (Manyika & Marima 2025: 66). The East African Revenue Authorities Technical Committee on Integrity (EARATCI) has organised biennial meetings for commissioners of tax authorities in the region since it was founded in 2014. The committee encourages the use of integrity measures such as ‘capacity building, informer rewards, proactive investigations, lifestyle audits, vetting, and integrity testing’ (KRA 2024a).

The EARATCI also launched the East African Revenue Authorities Integrity and Anti-Corruption Strategy 2023-2026 (KRA 2025). This framework provides guidance for tax authorities to implement measures such as integrity communication strategies, whistleblower frameworks, technological means of reducing interaction between tax officials and citizens and invest in staff training (KRA 2025). The Kenyan Revenue Authority stated that the ‘implementation of integrity initiatives has led to an 8% increase in the overall tax-to-GDP ratio among member countries’, however, it does not provide a breakdown or source for this statistic (KRA 2024a). The TRA is a member of the EARATCI but has not publicised specific actions taken relating to this initiative.

In 2024, Tanzania hosted a gathering of representatives from revenue authorities of East African Community member states on the theme of Enhancing Integrity through the Use of Technology and Data Analytics. The EARATCI called on member states to fully automate tax collection processes ‘to eliminate revenue loss caused by graft’ by decreasing the contact between tax officials and taxpayers and thereby reducing opportunities for collusion and extortion (Amos 2024).

Reforms at the Tanzania Revenue Authority

A 2016 empirical study in Moshi municipality found a significant relationship between the level of integrity of tax officials and rates of revenue collection by the TRA (Isaac and Kazungu 2016:1679). The authors therefore recommended that municipal councils conduct regular ethics and integrity training programmes, seminars and workshops for their employees (Isaac and Kazungu 2016:1681). Additionally, the study emphasised the importance of standards of conduct and clear monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for these standards.

Since then, there have been several integrity related reforms at the TRA. One author reports that the TRA has an anti-corruption strategy (Kiunsi 2021: 59) though this does not appear to be available on the TRA website. There are other signs that the TRA is taking anti-corruption within the agency increasingly seriously. The TRA recently published a press release in which the commissioner general ‘warned newly recruited TRA employees against engaging in corrupt practices in the course of performing their daily duties’ (TRA 2025c). The Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau (PCCB) also recently reaffirmed its commitment to work with the TRA to ensure tax compliance targets in Tanzania (The Guardian 2025). The two agencies work together to counter tax evasion and corruption to uphold the integrity of the tax system (The Guardian 2025).

The TRA has also established a whistleblower hotline that appears to allow for the public to report corruption and tax evasion anonymously (Malima, Pillay & Obalade 2022). Interestingly, Malima, Pillay and Obalade (2022) found in their study of the Arusha region that small-business owners who perceived that non-compliance with tax regulations exposed them to the risk that whistleblowers would report them to the TRA were more likely to comply with tax regulations.

The TRA has also engaged in capacity building workshops led by international bodies. For example, in 2024, the World Customs Organization (WCO) ran a risk management workshop with the TRA, organised under the WCO Anti-Corruption and Integrity Promotion (A-CIP) Programme (WCO 2024). It focused on various corruption risks and the need to formulate strategies to address these different risks involving different actors in the supply chain (WCO 2024).

In addition, the TRA has launched a public education campaign aimed at persuading citizens to adopt rule-following behaviour and move away from a culture of non-payment of tax (Bizlens 2025). According to the World Customs Organization (2024), the TRA is also adopting new risk analysis techniques, although there does not yet appear to be available data on the effectiveness of these measures. The International Growth Centre (2025) reports that, from 2022 to 2023, the organisation supported the TRA to improve the use of data generated by the electronic fiscal devices adopted in 2010, such as making it more accessible and linking it to other relevant databases.

Finally, Kyomo and Buhimila (2025:430) report that officials at the TRA have recently proposed setting up blockchain based tax ledgers to record all business transactions in real-time, to make it more difficult for taxpayers to evade taxes.

Other potential policy interventions

In the past few years, various recommendations have been advanced to improve integrity and reduce corruption in the Tanzanian tax administration. Shirima (2021:142), for instance, points to the fragmentation of taxation policies in Tanzania and the discretionary power of the minister of finance and commissioner general who both exercise influence over tax policies and implementation. Shirima therefore calls for a uniform interpretation of the tax law regime to ensure that the implementation and application of laws is consistent (Shirima 2021:144).

The Policy Forum (2025a:9-11) proposes numerous recommendations to curb illicit financial outflows from Tanzania, including amending the Tanzanian Tax Administration Act (2019) and the Investment Act (2023) to ensure that tax incentives are transparent, time-bound and performance based. These two acts provide the legal framework for tax collection, enforcement and compliance for taxpayers and investors in Tanzania.

The Policy Forum also recommends that the TRA sign automatic tax information agreements with key partners to monitor offshore activities, as well as improving cooperation with the FATF.55c9cbce4c61 Moreover, to counter losses from illicit financial flows, it calls for better coordination between the TRA, the Bank of Tanzania, the financial intelligence unit and the Ministry of Minerals, such as a joint task force to conduct joint audits and investigations into high-risk sectors (Policy Forum 2025a:10-11). In addition, it calls for the TRA to prioritise digital monitoring, mandate e-invoicing, and train TRA auditors and tax officers in forensic accounting techniques.

Through their research in Tanzania, Chindengwike and Kira (2021) recommend that to increase Tanzanian taxpayers’ voluntary compliance during self-assessment, authorities should increase the level of tax transparency. This point is further reflected in a study conducted by Omary and Pastory (2022), whose research in the Illala municipality in Tanzania found that maintaining tax fairness, appropriate and moderate levels of penalty for non-compliance, and tough measures to curb tax revenue corruption are key to increasing levels of tax compliance in the region. Concerningly, the Policy Forum (2025b) has observed that in recent years there has actually been a reduction in the publication of data on key revenue streams, including taxes and levies. While tax authorities sometimes share tax information with law-enforcement authorities, this is not automatic and poor cooperation between law-enforcement authorities is often a barrier to information sharing.

Furthermore, in their study on compliance at the TRA, Kyomo and Buhimila (2025:431) recommend that the agency should focus on community engagement initiatives; to build trust, foster understanding and cultivate a culture of voluntary compliance among the public.

Beyond recommendations put forward specifically in relation to Tanzania, the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (n.d.) provides policy recommendations to counter fiscal corruption more broadly. They propose that national governments:

- enhance the autonomy and capacity of tax administrations

- reduce taxpayers’ interactions with tax officials9a0b7161ec0d

- improve internal control, audits and oversight of tax agencies

- encourage whistleblowing751b7affea45

- establish credible penalties for non-compliance

Benchmarking against other sub-Saharan African countries

The Kenyan Revenue Authority

The tax authority of Tanzania’s neighbour Kenya publishes more communications about its integrity management systems than the TRA does, but little independent data exists to verify this information.

The Kenyan Revenue Authority (KRA) states that collaborative efforts for information exchange and data sharing among tax authorities in the region are underway. The automatic exchange of information (AEOI) platform enables participating states to exchange financial account information automatically. This eliminates the bureaucratic processes that can stymy cooperation and is a powerful tool for countering cross-border tax evasion (KRA 2024b).

The KRA has established an intelligence unit to support investigations into illicit financial flows, demonstrating an appreciation for the sensitivities and difficulties associated with gathering this information.

The KRA is committed to employing collective action as an anti-corruption method. It runs workshops in collaboration with the World Customs Organization in customs administrations to train staff to implement integrity measures (KRA 2024b). KRA also collaborates with the Kenyan Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission to train corruption prevention committees (CPC) and integrity assurance officers (IAOs) within the KRA (KRA 2024c).

The KRA has introduced technological innovations:

- iWhistle, a web-based platform that facilitates completely anonymous whistleblowing

- data-driven risk mapping to support investigations

- profiling of tax evaders (Kenya News Agency 2025)

Other integrity measures include compulsory ongoing lifestyle audits and asset tracing for staff. These measures are matched by statistics indicating increased enforcement measures against staff. Employees are supported by an integrity incentive scheme that offers rewards for ethical behaviour (Kenya News Agency 2025).

Zimbabwean Revenue Authority

A recent article claims that the Zimbabwean Revenue Authority (ZIMRA) is at the ‘forefront’ of regional initiatives to implement integrity measures (Manyika & Marima 2025: 66).

ZIMRA’s integrity promotion framework includes:

- recruitment policies providing for vetting and psychometric testing, prioritising integrity

- an asset declaration policy and lifestyle audits

- a policy prohibiting accepting gifts

- automation initiatives, including enhanced surveillance at border posts using drones and CCTV

- corruption risk assessments identifying ‘corruption hotspots’ (Manyika & Marima 2025: 66-77)

The article contends that these measures have been successful but contains no information about how this was measured.

Uganda Revenue Authority (URA)

Kim and Kim’s (2018) study found that Tanzania’s tax administration generally achieves better outcomes in terms of tax performance and tax compliance than that of the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA), even though they have introduced similar tax reforms. In particular, the authors note that Tanzania’s tax administration was more effective and accountable to taxpayers.

Their research finds that Tanzanians generally showed stronger support for the legitimacy of tax authorities than Ugandans, and this has been a longstanding trend (Kim and Kim 2018:55). Nonetheless, both countries have similar level of difficulties with transparency and the accessibility of tax systems; around 70% of Tanzanians and Ugandans answered in the Afrobarometer that it is ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ to get information about tax liabilities (Kim and Kim 2018:55); 85% of respondents from both countries responded that it is difficult to know how the government spends tax revenue (Kim and Kim 2018:55).

The study concludes that the TRA in Tanzania took proactive measures to collect tax liabilities and charged heavy interest rates and penalties for compliance failure and offences when compared to the URA (Kim and Kim 2018:57).

- It is worth noting that, in the absence of the collusion or complicity of a public official, acts of tax fraud or tax evasion by taxpayers are unlikely to be considered a form of corruption.

- Local government licences, charges, fees and levies are administered by local government authorities, while the Zanzibar Revenue Authority (ZRA) is responsible for collecting non-union taxes in Zanzibar: VAT, stamp duty, hotel levy and fees, licenses and duties.

- However, it has been reported that there have been inconsistent interpretations and applications of these laws (Shirima 2021:136).

- These electronic fiscal devices ‘automatically transmit information about business transactions’ to the TRA and help businesspeople to file tax returns electronically (Shirima 2021:138). However, in practice, observers have concluded that that these devices have ‘not improved the performance in VAT collections as expected’ (Shirima 2021:138; Fjeldstad et al. 2020: 3). [See also Buluba et al (2025: section 2.1)]

- The customs and excise department in the TRA is responsible for the overseeing of the customs sector in Tanzania (International Trade Administration n.d.).

- It should be noted that these figures are difficult to verify and should be considered estimates.

- Note: Tanzania was on the FATF grey list for over two years but has recently been removed (see FATF 2025).

- The TRA has in principle addressed this by not accepting cash payments from taxpayers, and instead payments are now made via banks.

- A useful resource for both public and private organisations is Internal whistleblowing systems: Best practice principles for public and private organisations (2022) from Transparency International, which supports organisations’ implementation of effective internal whistleblowing systems by highlighting best practice examples.