The number of specialised anti-corruption agencies (ACAs) has grown exponentially during the last three decades, especially since 2003 when the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) required the existence of such bodies in each State Party (Articles 6 and 36). Yet, there is little empirical evidence as to whether or why ACAs have been effective, amid criticism that some agencies are little more than ‘talking shops’ or vulnerable to instruments for political ends.b69c3cd103ba Further, while there is academic debate over whether countries should spread anti-corruption functions among several agencies or concentrate them in one overarching institution,fa004b5fa637 there is similarly a lack of evidence to help with resolving this discussion. More rigorous and comparable evidence of what factors enable and support the effective performance of ACAs will provide policymakers, civil society and ACA staff with the knowledge to request changes.

The agreement and international acknowledgement of the Jakarta Principles

In November 2012, UNDP and UNODC, in collaboration with the Corruption Eradication Commission of Indonesia, organised a meeting in Jakarta to develop a set of basic standards to guide the establishment and operations of ACAs. The 50 expert attendees, including more than a dozen current and former heads of ACAs from around the world, wrote the Jakarta Statement on Principles for Anti-Corruption Agencies. The statement’s 16 Jakarta Principles offer guidance on conditions for ACAs to have ‘necessary independence’.

The International Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (IAACA) endorsed the Jakarta Statement at its 2013 annual conference in Panama. It was also noted by the Conference of the States Parties to the UNCAC in 2013 in Resolution 5/4, Follow-up to the Marrakech declaration on the prevention of corruption and again in 2017 in Resolution 7/5, Promoting preventive measures against corruption.

The Jakarta Principles are normative principles based on the experience of expert drafters and what they consider to be good practice, and some scholars have recommended that, rather than taking them as an international benchmark, they should be treated with caution.90c9af6ce61a Indeed, there has never been systematic empirical research to test whether compliance with the principles – in their totality or as individual principles – is related to the effectiveness or performance of ACAs. The expert meeting on ACA performance undertaken as part of the International Anti-Corruption Academy’s (IACA) Global Programme on Measuring Corruption in the summer of 2023 identified this as an evidence gap and called for a systematic review of the effectiveness of compliance with the Jakarta Principles.cf5dd806d963

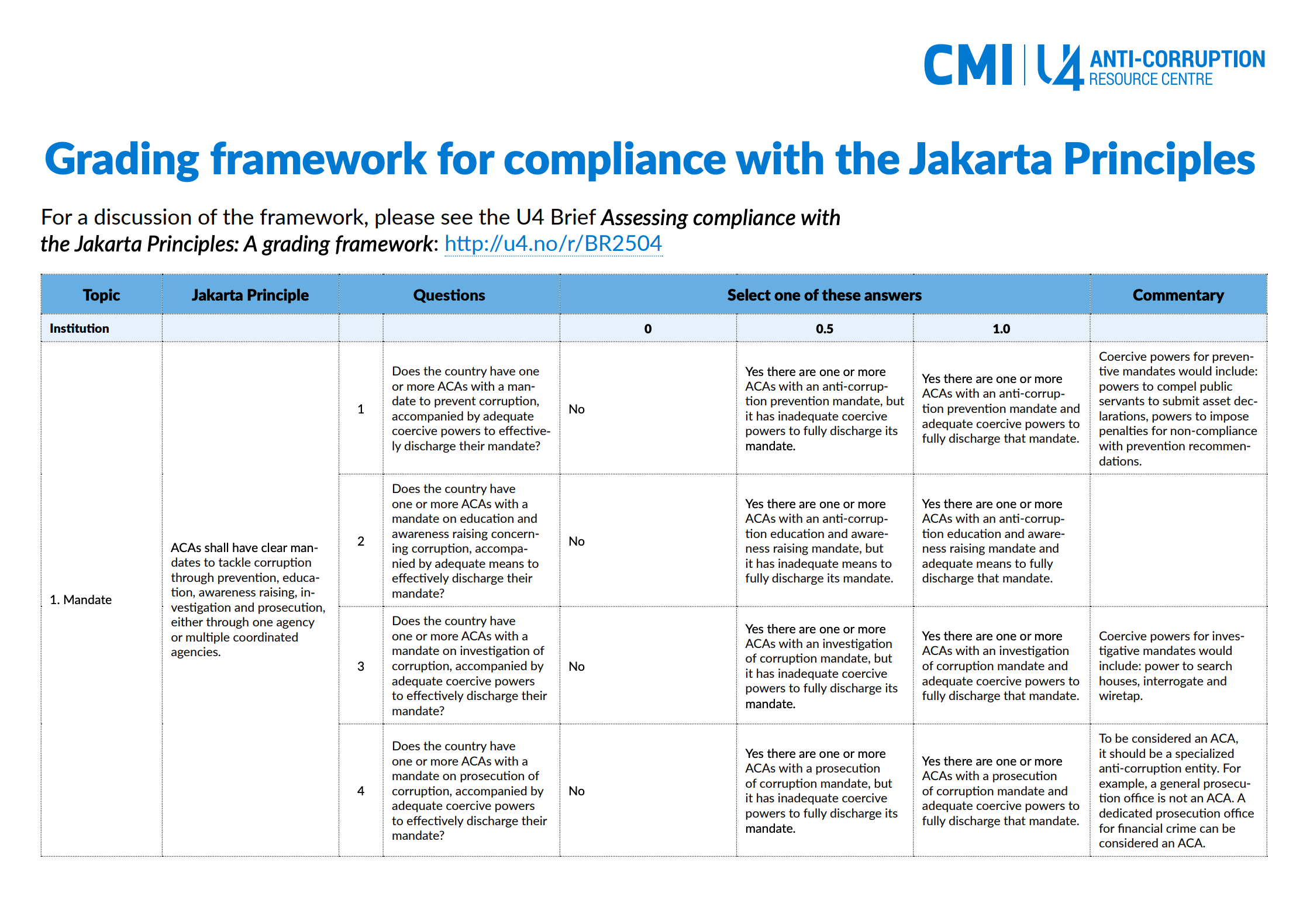

In fact, as part of the Colombo Commentary, a simple yes-or-no compliance checklist was developed in 2020. We are not aware of it having been used by anyone to collect data, but we have used this as our starting point. To operationalise the checklist for research purposes, we drafted more specific questions that allow for assessment of an agency’s compliance according to a three-point grading scheme. We then invited a group of professional and academic experts with backgrounds in law, economics and social sciences to review the draft framework and discuss their comments. The framework was then piloted using desk research to collect data on three ACAs in different regions. These results were presented to an international audience of around 50 specialists, from ACAs and experts who have worked with and on ACAs, who gave further feedback on the framework at a workshop at IACA in May 2025.

In the following sections, we discuss the rationale behind the grading and weighting of the different questions, our decisions about the appropriate scope and unit of analysis, some tricky questions that came up, and how we have attempted to resolve those questions. The framework is annexed to this Brief, thereby making it a public good. We conclude with our ideas on how to use compliance data for further research on performance and effectiveness.

Grading framework for compliance with the Jakarta Principles

Our grading framework evaluates anti-corruption agencies' adherence to the 2012 Jakarta Principles, providing a basis for linking compliance to improved effectiveness and evidence-based reform. It scores agencies on 50 questions across five themes (institution, leadership, human resources, financial resources, oversight).

The development of the grading framework

The Colombo Commentary contains a self-evaluation framework with more than 80 closed, binary questions. It does not allow for nuance or for distinguishing between de jure existence and de facto application of legal authorities.

Building on the Colombo evaluation framework, we organised the principles and questions along five themes: institution, leadership, human resources, financial resources and oversight. For each question, we allocated a score based on the assessment of the agency: 0 for non-compliance, 0.5 for partial compliance and 1.0 for full compliance.6e633566482a This will result in an agency having a score for every Jakarta Principle and theme, as well as an overall score for compliance. The framework contains 50 questions but they are not evenly distributed. The number of questions per principle varies from 1 to 7.

For example, for the principle on permanence, there is only one question about an ACA’s legal status: whether it is established by executive decree (0), law (0.5) or constitution (1.0), based on the assumption that establishment by the constitution is more likely to ensure continuity, which is the essence of the principle. By comparison, for the principle on adequate and reliable resources, six questions are needed to establish compliance because the principle specifies multiple dimensions of resources and provides guidance on how to assess adequacy and reliability.

To ensure that all principles have equal weight, scores for each should be standardised depending on the number of questions. With a multiplier (number of questions per principle / total number of questions [50]), it is possible to achieve a score of up to 50/16 per principle (3.125 on our scale). Given that there are 16 principles, this results in a total score of up to 50 points. The overall compliance could also be expressed as a percentage score. However, for research, if not policy purposes, overall scores or ranking are of less interest than how an ACA performs on individual questions, principles or themes. This may also allow the identification of patterns of compliance with the principles, for example, whether compliance in some areas is generally lower. For further research, it will be interesting to examine what, if any, a difference in compliance with individual principles or a combination of several principles makes against select performance indicators.

For two questions, we have retained the Colombo evaluation framework’s binary ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answers:

- Q 33: Is there a legally guaranteed minimum budget for the ACA?

- Q 41: Are the ACA audit reports published?

All other questions require judgements about the degree of compliance, posing a challenge about how to define partial (score 0.5) or complete fulfilment (score 1.0) of a question/criterion. The framework currently contains a column with explanatory comments, but these are not exhaustive. The grading sometimes contains assumptions or value judgements: De facto collaboration with other stakeholders (score 0.5) is considered stronger when it is formally conducted (score 1.0).

These judgements are informed by theory and experience as compiled for the Colombo Commentary and should be empirically tested. One reviewer of the draft framework remarked:

If collaboration among state organizations is laid down by law or decree, additional formalization may not be necessary or even not be foreseen in the legal system. Similarly, cooperation between ACAs and civil society organizations might face legal or factual hurdles that may lead to situations where factual cooperation is, in terms of the desired outcome and results, the most efficient way to join public and private forces. This may be equally true when it comes to cooperation with the private sector.

We have therefore moved away from the Colombo Commentary’s specificity of formalising collaboration with memoranda of understanding. The full score is gained when ‘The legislation requires or allows collaboration and it takes place on a formal, regular and continuous basis’ (Qs 5–9). We have not specified how data should be collected. One option is to have agencies self-report; another is to have a dedicated assessor grade all agencies in a sample. Both have limitations and may be subject to different kinds of biases. Thus, it important to provide further guidance, as far as possible, on what constitutes ‘sufficient’ and ‘adequate’ in the context of some questions. Independent verification and triangulation would certainly add to the rigour of future analysis, as would publication of results.

Unit of analysis

ACAs shall have clear mandates to tackle corruption through prevention, education, awareness raising, investigation and prosecution, either through one agency or multiple coordinated agencies (Jakarta Statement 2012, p. 2).

The first Jakarta Principle does not prescribe a particular model of ACA, but in the spirit of the UNCAC, wants to see countries clearly define core anti-corruption functions and assign them to one or several bodies. In developing the assessment framework, we had in-depth discussions on whether the unit of analysis should be an individual agency or an anti-corruption ecosystem, especially in those countries where mandates are split across several bodies. We concluded that the approach should depend on the purpose of the assessment. However, for the principle on mandate, we suggest scoring according to anti-corruption functions as spelled out in the Jakarta Principles: prevention, education, awareness raising, investigation and prosecution. Thus, a country with a corruption prevention agency and a corruption investigation body would get the same score as a country with a sole ACA that has both preventive and investigative mandates.

After these questions about the ACA(s) mandate, however, the unit of analysis of the questionnaire is a single agency (with whatever mandate it may have), and if there are several, the framework should be completed for each agency individually. To compare countries with different ACA models, that is, a multi-agency model and a single-agency model, an average score would have to be calculated for the multi-agency model. This could help identify the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches and their performance outcomes. Alternatively, the framework could be used to assess agencies of a certain model only.

Tricky questions

Finding good indicators of compliance with the principles is particularly challenging when it comes to defining what is ‘adequate’ and ‘sufficient’ and what marks partial fulfilment.

For example, this is the case in terms of the development of a good measure for the complex principle on adequate and reliable resources:

ACAs shall have sufficient financial resources to carry out their tasks, taking into account the country’s budgetary resources, population size and land area. ACAs shall be entitled to timely, planned, reliable and adequate resources for the gradual capacity development and improvement of the ACA’s operations and fulfilment of the ACA’s mandate (Jakarta Statement 2012, p. 3).

It is not by coincidence that the evaluation framework in the Colombo Commentary leaves the judgement on ‘sufficiency’ to the eye of the beholder: ‘Is the current ACA budget sufficient to ensure that the ACA can effectively discharge its mandate?’

One difficulty here lies with translating this into indicators that allow for accurate comparisons across contexts that vary widely in terms of size of economy and extent of corruption risk. One suggestion (Q 35), drawing on a 2012 study by De Jaegere showing a positive correlation between a budget of US$1 per inhabitant in the country for the ACA and country rankings in global corruption indexes, was to set US$1 per capita as a threshold for compliance. However, neither the mandate of the 20 ACAs that were part of this study nor purchasing power in the country were considered in these calculations.

Another indicator (Q 36), used by the Transparency International ACA Strengthening Initiative (2017), localises the indicator by putting the ACA budget in relation to the overall national budget. Sufficiency is reached when the ACA budget reaches or exceeds 0.2% of the national budget. This indicator also does not consider different ACA mandates.

A more nuanced approach, suggested by one of the reviewing experts, is to establish a ratio of the ACA’s budget allocated to core functions that directly relate to its mandate or a budget sufficiency ratio estimating the budget that the agency needs to fully implement its core programmes and operations, for example, the total budget allocated to the agency divided by the estimated budget needed to fulfil and meet the objectives outlined in its mandate multiplied by 100. However, calculating such an estimate using the same methodology would take extra time and resources for the completion of this assessment. For now, we have left in the indicators for expenditure/capita and percentage of national budget and invite fellow researchers to determine alternative, easy-to-use (proxy) indicators to measure budget sufficiency.

In general, we have sought to be faithful to the principles and evaluative framework of the Colombo Commentary. However, the principle on removal contains specific reference to the removal process of a chief justice, as it was deemed particularly rigorous and a relevant benchmark by the developers of the Jakarta Principles:

ACA heads shall have security of tenure and shall be removed only through a legally established procedure equivalent to the procedure for the removal of a key independent authority specially protected by law (such as the Chief Justice; Jakarta Statement 2012, p. 2).

A comparative study of the legislation of 46 ACAs found that by 2015 in many countries, the procedures for removing the head of an ACA were vague and open to misuse by those in power. While removal often requires a criminal conviction, ambiguous terms like ‘misbehaviour’ or ‘incompetence’ are used without clear definitions. In some jurisdictions, removal decisions involve legal review by public prosecutors and final rulings by high or supreme courts.87c2f618d0bf

Removal processes for ACA heads should consider a country’s political and institutional context. In competitive regimes, ACAs may enjoy independence akin to courts, especially if public support matters to ruling parties. The strength of parliamentary veto powers varies, influencing executive control. Though no universal method suits all, removals should follow transparent, open procedures involving multiple stakeholders – government branches and civil society – rather than sole executive discretion. Clear criteria for removal help prevent the misuse of power and protect agency integrity. A well-structured removal process ensures accountability and shields ACA leaders from arbitrary or politically motivated dismissal.178bf4c2d558

As removal processes for chief justices are often problematic, we decided to include two questions and indicators for due process, without benchmarking the process to other key independent authorities such as a chief justice:

Q 16: Is there a legally established procedure for the removal of the ACA head involving at least two different branches of state?

- No procedure is legally established (score 0).

- Yes, the process is legally established but involves only one branch of state (score 0.5).

- Yes, the process is legally established and includes at least two branches of state (score 1.0).

Q 17: Does the ACA head’s removal process require that certain limited grounds of misbehaviour or incapacity be proven in order to be triggered?

- No such grounds are required or grounds are required but determined by the executive only (score 0).

- Grounds are required and to be approved by legislature or judicial body or oversight body or ACA itself (score 0.5).

- Grounds are required and to be approved by legislature or judicial body or oversight body or ACA itself and ACA head is able to publicly defend themself against any charges (score 1.0).

What’s next? A foundation for research on effectiveness

This framework is offered as a public good, with the aim of enabling researchers to bridge the evidence gap by exploring the relationship between ACA adherence to the principles and anti-corruption performance. Such research could inform the practice of ACAs worldwide, empowering reform by linking institutional design to real-world anti-corruption performance and might lead to modification or updating of the Jakarta Principles or the development of alternative benchmarks.

However, to build a robust evidence base, data must be collected with care. When we piloted the framework in late 2024, by collecting data for three ACAs from different regions, we found that only around half of the questions could be answered based on readily available online public resources. Hence, follow-up interviews to complete the assessment would be required. These interviews could also be used to verify the information, which is also critical for rigour.

We have since simplified the framework, and would recommend further piloting to help identify specific needs for more elaborate guidance on individual questions.

While the degree of ACA compliance with the 16 Jakarta Principles may be of interest for its own sake, the ultimate aim behind the development of this framework is to use assessment findings to empirically and systematically test whether (non-)compliance with several or all principles results in a significant difference in the performance of ACAs.

Such research could seek to explore statistical relationships between a) compliance levels as determined through our methodology and b) other indicators of corruption or anti-corruption performance. Any such quantitative analysis would require careful decisions about the most appropriate performance indicators for the dependent variable and recognise the limitations of such research. An initial attempt at this was undertaken by Transparency International (2017) by correlating enabling and performance indicators of its tool.

There is considerable potential for research to identify whether certain minimal levels of compliance or adherence to specific principles or sets of principles is relevant to performance. We further recommend studying cases of changes in compliance over time. This could help identify the effect that a change in compliance has on performance, particularly if the framework is combined with more precise local indicators and qualitative interviews.

Huge resources are being invested in the creation of ACAs worldwide. Yet, at the same time, there is widespread disillusionment with the lack of success of anti-corruption efforts. This framework is offered as a resource to underpin research towards improving our evidence base about what works. We encourage academics and practitioners to trial it, critique it and adapt it – and to share their results with the wider community.

Grading framework for compliance with the Jakarta Principles

- Eg De Sousa 2010; Smilov 2010; UNDP 2005; Heilbrunn 2004; Meagher 2005; Mungiu-Pippidi et al 2011; Amundsen and Jackson 2021.

- Eg De Speville 2010; OECD 2013; Mota Prado and de Mattos Pimenta 2021.

- Stephenson 2015.

- Schütte, Ceballos, and David-Barrett 2023.

- The scores can easily be adjusted to 1, 2 and 3 or any ordinal scale.

- Schütte 2015.

- Schütte 2015.