Blog

Greenwashing: A form of corruption

Everyone seems to be talking about greenwashing. Environmentalists, politicians, business leaders, consumers, investors, risk consultancies, the UN, and development banks all are worried about it. But before the 2000s the word was the almost-exclusive preserve of the environmental movement. It perfectly summed up the way in which corporate environmental claims hid a host of environmental ‘sins’.

Indeed, the term was first coined back in the 1980s by Jay Westerveld, a New York environmentalist, as a comment on hotels placing stickers with slogans like “Save the environment, re-use your towels” in their rooms. Greenwashing, here, was about the hotel industry taking no further substantive actions to reduce their environmental impact, whereas reducing the amount of laundry would help the industry save costs.

What is greenwashing?

Most definitions of greenwashing describe processes of conveying false or misleading information about activities, organisational procedures, products, or services having positive impacts for the climate. Many have argued that greenwashing is a result of consumers’ growing ‘environmental consciousness’ – and the cynical assessment of the same by corporate actors. In this view, corporations aim to hide their environmentally and socially damaging practices behind a veneer of climate action, allowing them to cash in on concerns about climate change. The term has become very broad, covering false advertising, eco-labelling (the process of giving products or services labels that aim to convey messages about the sustainability of products), product design (using green colours, or vague terms like “natural”), and using green messaging to shield companies or governments from broader social, human rights, or environmental criticisms.

Standard definition of greenwashing

The process of conveying a false impression or providing misleading information about how a company’s products, services and/or business practices are more environmentally sound than they actually are. Greenwashing is based on some type of unsubstantiated claim with the aim to either deceive relevant stakeholders into believing that actions/products/services etc are environmentally friendly or misdirect criticism about the environmental and social harm of the same actions/products services etc.

Greenwashing and corruption

The link between greenwashing and corruption was made glaringly obvious with the discovery of Volkswagen’s carbon emissions fraud. This led several actors to produce guidance on the links between greenwashing and fraud. In academic discussions in the field of business management and organisational ethics, this link between greenwashing and fraud is well established.

Multilateral development banks are also acutely aware of the risk that greenwashing can pose to their investments. Indeed, greenwashing in international development is becoming better understood. Several studies have been produced in recent years about the uptake by corporate actors of the Sustainable Development Goals and the links to greenwashing (see for instance, Lashitew 2021 and Pimonenko et al. 2020). Of broader concern, however, is the relationship between climate financing of development projects (mainly in renewables) and greenwashing. Achiba Gargule’s work on the Lake Turkana Wind Power Project is particularly insightful. The project in Kenya was funded by The Finnish Fund for Industrial Cooperation and the Danish Climate Investment Fund, supporting a consortium comprising Vestas (a Danish wind turbine manufacturer), Milele (an African energy company founded by former GE executives), and Anergi (an energy company managed by the South African management company Harith General Partners). Gargule demonstrates how the green credentials of the project (as a renewable energy initiative), combined with some – very limited – social responsibility initiatives, were used to greenwash serious allegations of corruption regarding ‘irregular’ land acquisitions which deprived Indigenous People of their rights, as well as alleged human rights abuses. The case is currently in the Kenyan courts.

5 points to consider

In 2018 the Oxford English Dictionary described corruption as “dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those with power” (cited in Corzo and Praes 2019). By this definition greenwashing is certainly corruption. Even if we use the most common definition of corruption: “abuse of entrusted power for private gain”, there are five important dimensions to the connection between corruption and greenwashing that must be considered.

- On a basic level we can agree that corporate actors have a lot of power, which is entrusted to them by shareholders, consumers, governments, and others. So when they knowingly promote a green image based not on a systematic reconfiguration of their business practice but through misleading narratives of low-impact green initiatives, they are essentially abusing this power in order to gain an unfair advantage in the market. This advantage results in private gains through increased profits.

- The chief argument in establishing the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in the United States was that bribery gives an unfair competitive advantage and distorts the market. Without proper assessment of ‘green claims’ or corporate social responsibility initiatives, greenwashing can have a similar effect.

- As consumers and stakeholders become aware of greenwashing as a business strategy, the continued use of greenwashing harms those companies that are serious in their efforts to reduce their own environmental impact by eroding public trust in private sector actors generally. Trust in climate initiatives (beyond the private sector) may suffer from greater public mistrust and this could lead to negative environmental impacts.

- Greenwashing can be fraud. A key example here is the Volkswagen carbon emissions scandal.

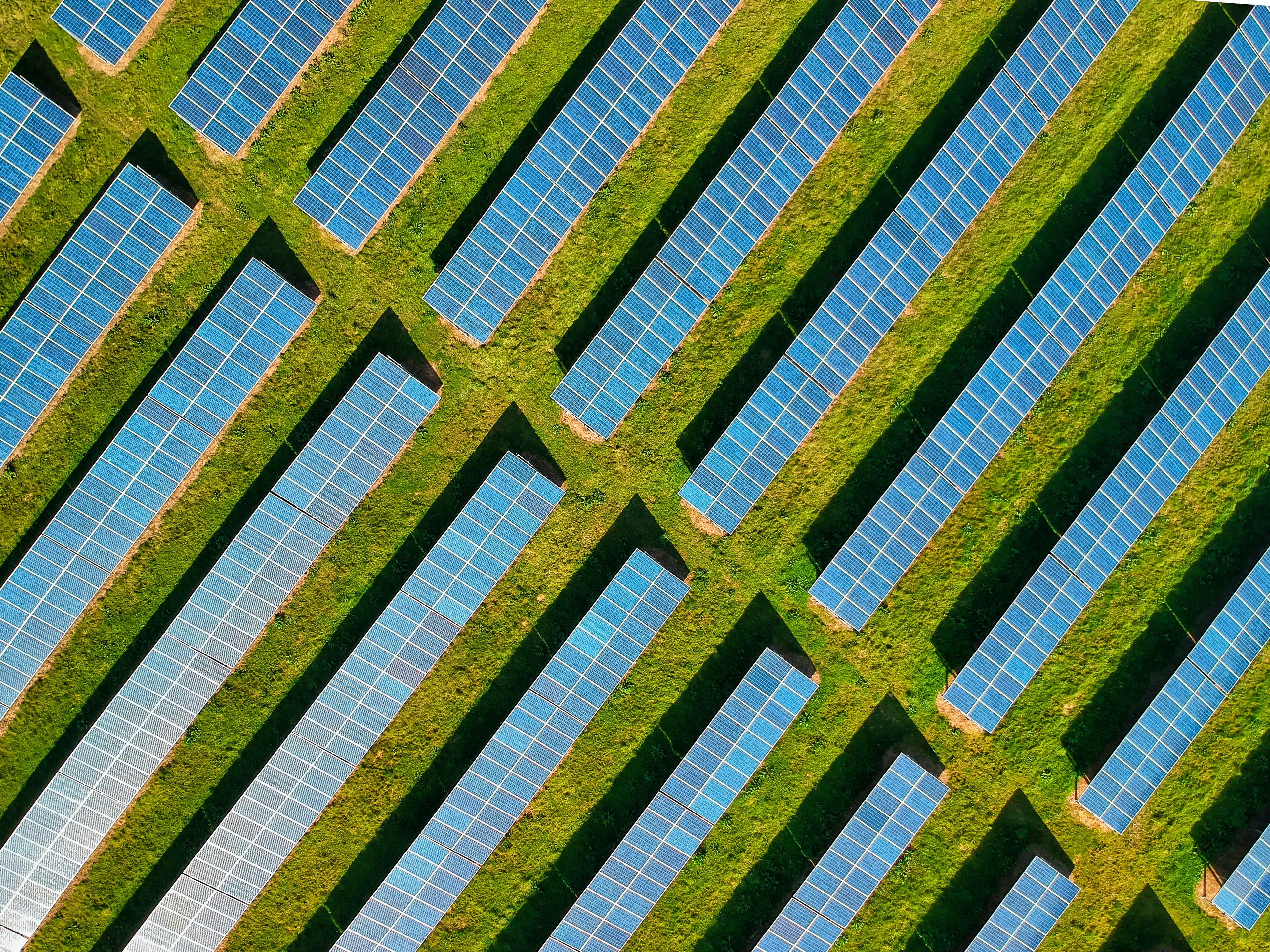

- Corruption can be greenwashed. For example, land registry officials can be bribed so that green-energy companies can bypass land laws, allowing the purchase or lease of land for wind or solar farms.

Greenwashing is corruption

There are of course, people in the private sector with a desire for a more sustainable world and who understand the responsibilities of business beyond profit maximisation. But the primary job of corporations is to make more money for their investors and shareholders. This will, sadly, be the primary goal no matter how ethical a company may be. That means there is always a possibility of conflict between the profit motive on the one hand and ethical responsibilities on the other. We can already see the results of this conflict in lacklustre climate efforts: addressing climate change doesn’t really make much money. For consumers, it is difficult to see the difference between genuine environmental concern and cynical profiteering from green messaging. And that is a huge problem.

It is a problem because, like it or not, business has a lot of power in our world. This power comes not just from their size, market share, and disproportionate political influence, but also from the power entrusted to them by shareholders, investors, consumers, and governments. They abuse that power if they promote misleading green messages. They benefit from that abuse of power through increased profits and market share. Yes, profits might be reinvested, but profits are also private gains. Greenwashing, in my opinion, is a type of corruption and should be treated as such.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)