Blog

Accountability deficit: Why do citizens vote for corrupt politicians?

This is a guest post for U4 by Manoel Gehrke, Nic Cheesemanm, and Licia Cianetti from the Centre for Elections, Democracy, Accountability and Representation (CEDAR) based at Birmingham University, UK.

Following flawed elections in Gabon and Zimbabwe – and as election campaigning hots up in the United States – corruption is increasingly in the news. Opposition parties in all three countries allege the incumbent government is corrupt and deserves to lose power. Yet this message is controversial and citizens may lack the information needed to effectively evaluate such claims. While many of the wild allegations made by Donald Trump in the US are demonstrably false, citizens in Gabon and Zimbabwe face a heavily restricted media environment,which makes it even more difficult for them to accurately assess and evaluate the information they receive. This raises an important question: when do citizens punish governments following corruption accusations?

The idea that citizens punish corrupt government is fundamental to the idea of democratic accountability, and is as important to the health of a political system as it is to the fight against graft. So what does the evidence tell us? Unfortunately, the picture is decidedly mixed. While politicians are more likely to be voted out of office in countries where governments are more corrupt, there are many reasons – including disinformation and their own self-interest – why citizens may keep voting for corrupt candidates. In so doing, they become complicit in the deterioration of their own democracies.

Corruption and re-election: The global picture

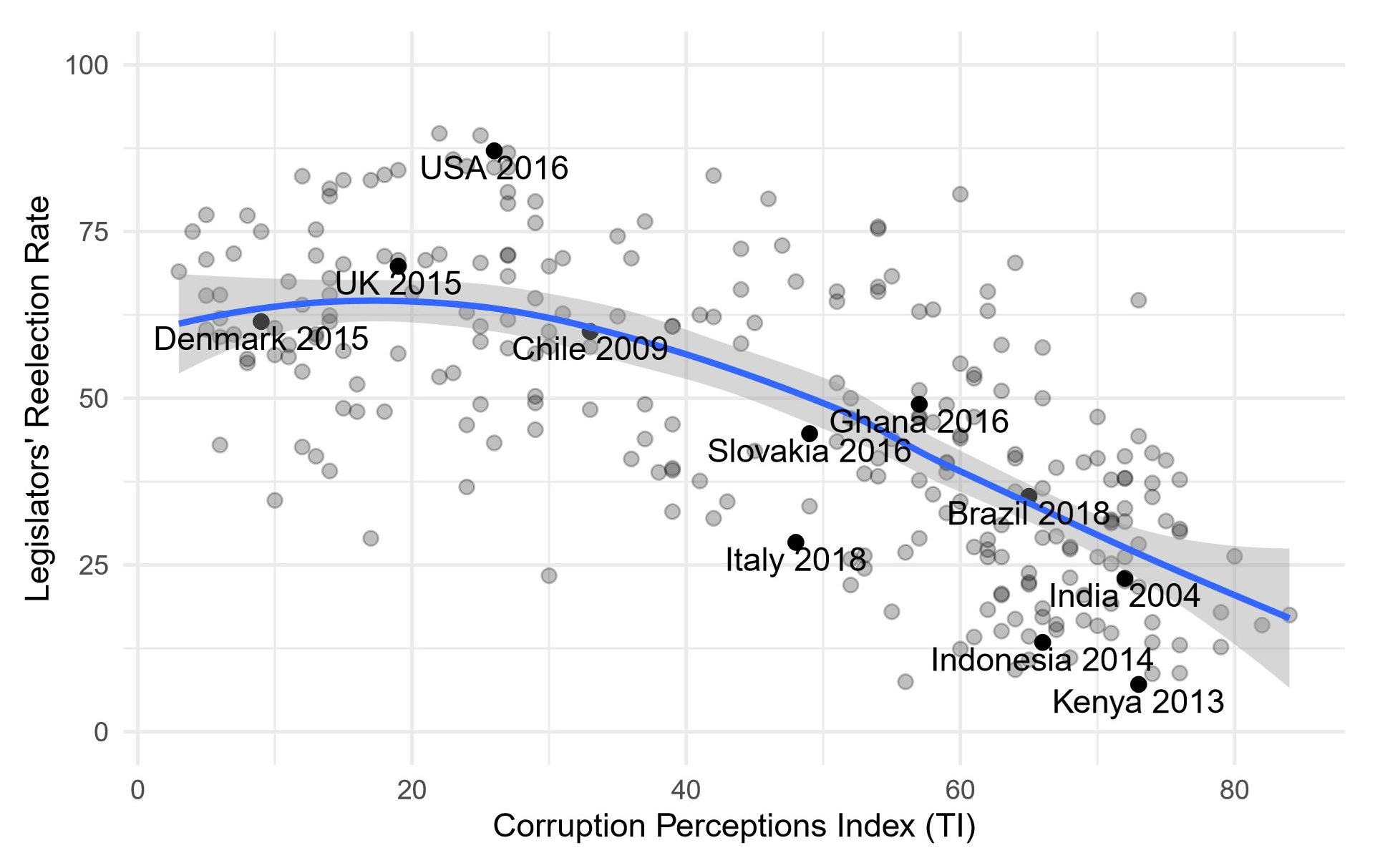

Building on a recently released dataset for 262 national elections across 63 democracies between 2000 and 2018, our analysis reveals that citizens are less inclined to re-elect politicians in countries where governments are seen to be more corrupt. This suggests that they may be responding to frustration with graft by punishing those in power, especially as this relationship holds even when we control for each country’s level of economic development. The magnitude of this correlation is dramatic: in countries where perceptions of corruption are low, most legislators win re-election, but where corruption is high, most are defeated.

Figure 1. Re-election rates and Corruption Perceptions Index (2000–2018)

Note: Data on legislators’ re-election rates from Martin, McClean and Strøm (2023) and data on Corruption Perception Index (CPI) from Transparency International. The line is fitted with a local polynomial regression. We reversed the CPI scale to make interpretation easier.

Citizens’ demand for accountability is not the only thing that might explain this pattern, of course. The existing literature tells us that incumbent members of parliament are more likely to keep winning in countries that have been democracies for longer and have more institutionalised party systems. This means that we would expect to see countries such as Denmark and the UK higher up in Figure 1, and Indonesia and Kenya lower down.

However, numerous cases do not fit with the predictions of previous theories, providing further evidence for the idea that we need to factor in corruption perceptions to fully explain where countries are located in Figure 1. This includes relatively new democracies such as Chile and Ghana, where re-election rates are higher than existing theories would suggest, and long-standing democracies like India and Italy, where they are lower. To explain the distribution of countries in Figure 1 we therefore also need to factor in the way that perceptions of corruption can shape satisfaction with the status quo, no matter how long a country has been a democracy. In Italy, for example, persistent concerns about corruption erode trust in elected representatives and drive citizens to vote for change, despite the fact the country has been a democracy for a long time.

This suggests that the relationship between perception of corruption and re-election rates is causal and not just coincidental. In turn, we need to think carefully about how the existence of this relationship shapes the beliefs and actions of politicians and citizens.

Looking through politicians’ eyes

If we look at the situation through politicians’ eyes, the lower chances of remaining in office in countries where corruption is higher will not necessarily encourage them to be clean. Members of parliament operating in unstable political environments with high turnover rates might decide to try and steal funds at an even faster rate given the short time that they can expect to stay in office. In addition, politicians may become more attentive towards special interests that can look after them if they end up outside of government, such as businesses, and spend more time cultivating friendships within the judiciary.

This fits with a broader pattern identified in Sub-Saharan Africa following the introduction of multi-party elections in the early 1990s. In countries such as Kenya and Zambia the need to raise funds to fight elections, and the pressure to raise funds in order to contest upcoming elections, meant that rates of corruption in some cases went up rather than down.

Critical citizens and the perils of populism

Political leaders face particularly low incentives to stay clean in countries where voters struggle to carefully distinguish between individual candidates. In such cases, politicians may not be held accountable for their own bad actions and decisions, and so voting patterns do not accurately reflect politicians’ performance. It is therefore important to consider the information available to citizens and the incentives that shape their behaviour.

Voters operate in challenging informational environments and candidates often accuse their rivals of being corrupt in order to gain political advantage or mask their own failings. This makes it harder for citizens to differentiate between politicians, and to hold corrupt leaders accountable, especially when the formal media is heavily politicised, and leaders deploy disinformation via social media.

When this happens, blame may not attach to any individual politician so much as the political class more broadly. In turn, this helps to explain why the spread of mobile broadband internet has increased voter disillusionment with politics. It is also a large part of the explanation for why evidence of corruption can undermine trust in the broader political system and increase support for populist ideas. Most notably, it plays straight into a core claim of populist leaders, namely that the entire establishment is ‘rotten’ and that only an ‘outsider’ can be trusted to put things right.

In this way, concern about corruption can propel populist leaders to prominence, such as Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and of course Trump in the US. The rise to power of populists on anti-corruption tickets might initially appear to be an opportunity to develop a cleaner form of politics. In reality, populist leaders – whatever their campaign slogans – have typically been more corrupt than the leaders they replaced. Once in office, their efforts to centralise power and weaponise checks-and-balances institutions against political enemies leave political systems even more vulnerable to corruption.

The combination of populist claims that the system is corrupt, and evidence of the corruption of populist leaders themselves, is particularly toxic because it encourages voters to believe that dealing with graft is impossible. Research on anti-corruption campaigns in countries such as Albania and Nigeria finds that the very messages designed to inspire anti-corruption sentiment often have the opposite effect. One reason for this is that the act of prompting individuals to think about corruption ‘primes’ them to think about how widespread the problem is, and this encourages them to ‘go with the flow’ rather than inspiring resistance. Researchers have found, for example, that exposure to certain anti-corruption messages made people no more likely to report instances of graft, and more likely to pay a bribe.

No easy answers

Popular apathy is especially worrying because citizens often have incentives to vote for corrupt leaders. In winner-takes-all political systems, for example, voters may tolerate corruption among leaders of their own party or ethnic group because they expect to share in the proceeds, or to be worse off under the leader from a rival party or ethnic group. Under these conditions, voters may consciously choose to vote for corrupt candidates, undermining any incentive for reform.

The complex consequences of corruption allegations reveal just how challenging it can be to ensure political accountability. Neither the tendency for voters to reject sitting legislators in more corrupt countries, nor revelations about corruption scandals in the media, necessarily lead to straightforward gains either for the fight against graft or the consolidation of democracy. This raises profound questions about how democratic political systems can cope with corruption, and corruption allegations, in contexts in which politicians are savvy, media headlines contradict each other, and voters are confused and tired.

Ensuring that politicians are held accountable is therefore a formidable challenge, but it is not an impossible one. Our research suggests that despite the many factors that blur lines of accountability, voters are more likely to reject incumbents in countries where perceptions of corruption are higher, and that is a powerful instinct that can be harnessed to promote cleaner politics in the future. Efforts to further strengthen accountability should focus on addressing the barriers identified above, enabling citizens to better understand which leaders are responsible for which actions and policies, establishing respected and authoritative sources of information on politicians’ performance that gain public trust, and showing citizens that even if they expect a short-term benefit from their leaders acting in a corrupt manner, the long-term effect of graft is higher taxes and poorer public services that leave them worse off. This is no easy task, but countries that achieve it will begin to win the battle against corruption.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)