Query

Please provide a summary of the key AML/CFT risks of mobile money services and regulatory approaches to mitigate these risks, with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa.

Nature and extent of mobile money services

Mobile money services have risen to prominence in recent years – and especially since the COVID-19 lockdowns – as a means of replacing cash in financial transactions without relying on formal bank accounts, particularly in low and middle-income countries (Dornbierer 2020).

FATF (2013) has categorised mobile money services (particularly mobile payments) as one of a series of new payment products and services (NPPS). These are innovative payment methods that offer traditional financial services via new means: in the case of mobile money, mobile phone technology.

Specifically, mobile money services refer to a mobile-phone based financial service that enables digital money transfers, payments and storage. Mobile money services provide for the use of mobile money (or m-money), a form of electronic currency (or e-money) whose value is either stored directly on a mobile phone or linked to a mobile phone account obtained by clients upon registration for the service (Kersop & Du Toit 2015a).beed6e55b2d2

Mobile money services are primarily targeted at/designed for people who lack formal bank accounts (also known as the unbanked population). These services are facilitated by a network of agents and are distinct from traditional mobile banking services (Aron 2017; GSMA 2025).

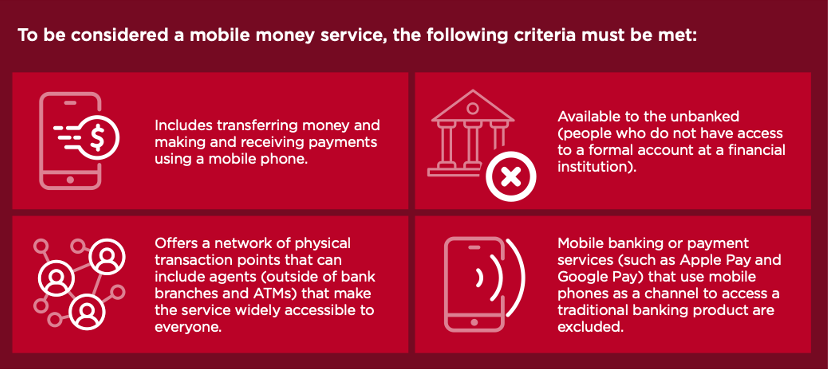

The criteria that define mobile money services are summarised in the Figure 1 below, created by the Groupe Speciale Mobile Association (GSMA 2024b), the worldwide trade association of mobile network operators.

Figure 1: What is a mobile money service?

Source: GSMA 2024b

Unlike mobile banking, which requires a bank account and uses smartphone applications to access banking services, mobile money services can be accessed using a basic mobile phone and do not require a bank account (Shirono et al. 2021). Mobile money payments or transfers are common in low and middle-income countries whose economies are largely cash based and where a large share of the population does not have access to a bank account. These mobile money payments are distinct from so-called mobile payments (e.g. Apple Pay), which are linked to existing bank accounts and are more typical in developed economies (Aron 2018).

Moreover, mobile money systems are managed through an extensive network of agents rather than traditional bank branches. These agents typically operate under various contractual arrangements with a parent mobile network operator (MNO), often in collaboration with a bank (Aron 2018).

Table 1: Comparison table: Mobile money vs. mobile banking

|

Mobile Money |

Mobile Banking |

|

|

Bank account |

Not needed |

Required |

|

Provider |

Mostly MNO but can also be a bank, fin-tech company or other |

Bank product |

|

Types of transactions |

Mainly P2P and P2B but other types of transactions also possible and increasingly used |

All kinds of transactions |

|

Banking |

Done by agents via shops and retail outlets |

Done by bank employees via bank branches |

Source: Based on Sharma 2014, modified by the author

Actors involved in mobile money services

There are several actors involved in the provision of mobile money services, and the way they relate to each other can vary significantly across countries and jurisdictions. According to Jenkins (2008), some of the main actors are:

- mobile network operators (MNOs): lead mobile money service delivery by providing the platform and offering customers access through mobile phones. They often coordinate with other actors in the mobile money ecosystem to expand reach and ensure operational reliability.

- banks: hold and safeguard customers’ funds associated with mobile money in dedicated trust accounts. They play a custodial role to ensure financial security and regulatory compliance. Furthermore, they might also develop their own mobile money products and services (FATF 2013).

- agents: serve as the frontline for customer interaction and are typically small business owners operating retail shops. Their responsibilities include onboarding new users, providing local support and cash-in/cash-out operations, for which they are sometimes referred to as CICO (Ahmad, Green and Jiang, 2020).

- customers: are the end users of mobile money services, typically using them for transactions such as transfers and payments through their mobile phones.

- regulators: are authorities that create an enabling environment as well as regulation for mobile money. They also monitor and enforce its compliance. These can include financial as well as telecommunication regulators.

- businesses, employers, merchants: businesses and employers may use mobile money to pay wages or accept payments.

Additional actors and types of service providers can be involved in a mobile money ecosystem, such as fin-tech companies or mobile telephone equipment manufacturers, payment networks, software developers or telecommunications industry standards setting groups (FATF 2013).

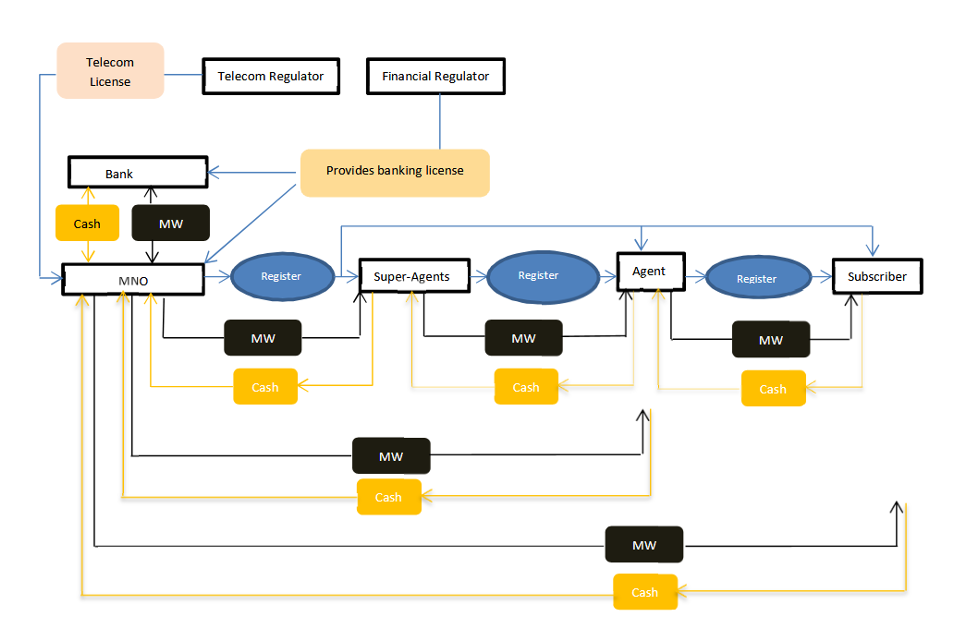

Different types of tiers of agents also exist, whose roles and levels of responsibility can differ across mobile money systems, as well as across countries.cc39bf5b6ce1 The actors interact in a complex layered manner, as shown in Figure 2, which describes the mobile money system in Ghana (MW stands for mobile wallet).

Figure 2: Actors involved in the MTN Ghana mobile money system

Source: Williams 2013

Opening a mobile money account typically begins with the customer visiting a registered agent or service provider outlet, such as a shop affiliated with an MNO. The customer is required to present a valid form of identification, such as a national identity card or a driving licence. The agent captures the customer’s details, registers the SIM card (if not already registered) and creates a mobile wallet account linked to the customer’s phone number (Tobbin 2011).

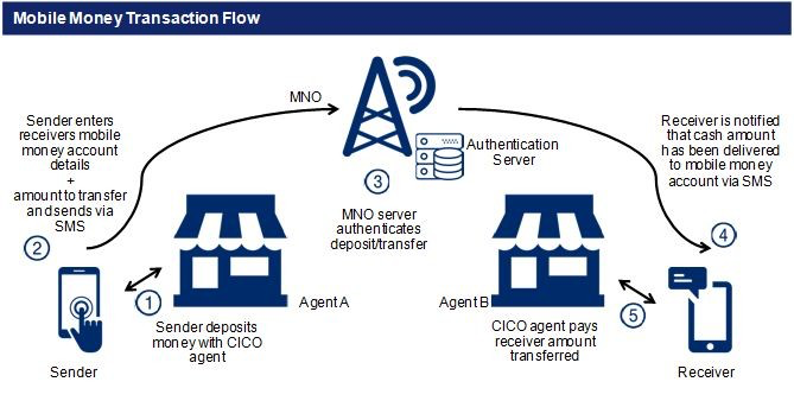

Once the account is activated, the customer can use the account to deposit, withdraw, transfer money or make payments, for example. To send money via a person-to-person (P2P) transaction, the sender needs to first cash in their mobile account via an agent and then accesses their account using a simple code-based menu (or mobile app if the sender owns a smartphone). The agent enters the recipient’s mobile number, the amount to transfer and a PIN to authorise the transaction.10cf884adbec The recipient instantly receives the funds on their mobile money account, which they can use directly or withdraw as cash through a local agent (Aron 2017; Tobbin 2011).

There are also mobile money services offered primarily over the counter (OTC). In such cases, a mobile money agent performs the transactions on behalf of the customer, who does not need to have a mobile money account to use the service. In some cases, the customer does not even need to verify their identity (GSMA 2015).

Figure 3: Mobile money transaction flow

Source: Douglas 2016

While mobile money services operate through mobile money accounts, typically provided by an MNO or in collaboration with one, there can be different models of mobile money service provision, depending on the entity that takes on the role of issuing the mobile money. FATF (2013) differentiates between three main models of mobile money services according to the type of provider.

- Mobile network operator (MNO) model: mobile money services are typically provided by MNOs, or in partnership with one, through mobile money accounts. In the MNO model, mobile payments are essentially an extension of telecom services, with customer funds typically held in prepaid accounts managed by the mobile operator or its affiliate or, in some jurisdictions, a partner bank. In this model, MNOs bear the operational and financial responsibility (FATF 2013). Notable examples are M-PESA in Kenya, M-Pitesan in Myanmar and MTN mobile money in Uganda (Shirono et al. 2021).

- Bank-centric model:mobile money services may be provided by formal banks, which differ from traditional mobile banking services as mobile money services are not tied to specific bank accounts held by one of the bank’s customers. In bank-centric mobile money services, a bank “either develops new products offered through the mobile phone to serve the previously unbanked, which are tied to limited transaction accounts or, alternatively, is a provider of electronic money that is not tied to a payment account” (FATF, 2013:7). Eazy Money in Nigeria is such an example (Shirono et al. 2021).

- Between a fully bank led and MNO led models exists a hybrid approach in which financial institutions and MNOs collaborate to provide mobile payment services through shared agent networks, targeting areas underserved by traditional banks. In this setup, MNO retail outlets and partner retailers function like limited-service bank branches, handling customer registration, deposits and cash withdrawals, often under the branding of either the bank or the MNO (FATF 2013). An example is the South African collaboration between Nedbank and Vodacom to re-launch M-PESA in the country (Kersop & Du Toit 2015a).

These different models can coexist within a country with other models, such as the “third-party led model”, which is a variation of the MNO led model where another party assumes the role of mobile money issuer (e.g. OPay and Palm Pay in Nigeria, started by an internet provider Opera). The MNO led model can therefore be also referred to as a “non-bank led model”. The majority of mobile money services are MNO led; in sub-Saharan Africa and Middle East and North Africa nearly two-thirds are MNO led (Shirono et al. 2021).

It is also important to note that these models describe simplified scenarios and, in practice, more complex models exist with overlapping roles of various actors within the mobile money ecosystem. Other providers and actors include mobile remittance services or mobile payment platform operators (Chatain et al. 2011). Nevertheless, these models might offer a useful starting point for comparability and understanding the different regulatory regimes based on the different models.

Typology of mobile money services

Transactions conducted via mobile money can take place between all types of users, including person-to-business (P2B), person-to-person (P2P), business-to-business (B2B) or government-to-person (G2P) (FATF 2013; Shirono et al. 2021).

From the perspective of end users, mobile money services involve a range of products that use mobile phones to conduct basic financial transactions such as transferring money, paying bills and accessing savings and credit (GSMA 2025).

Some services are prepaid, as when customers cash in funds via agents, who in return issue them mobile money that the customers can transfer further. Other mobile money services can be post-paid, meaning they are paid only after the service or purchase has been made. In that case, MNOs can be regarded as providing short-term credit, loan or payment schemes (FATF 2013).

Mobile money users can receive salaries into their mobile money account, transfer them to family and friends in the country or internationally using the same agent network. The services have gradually been expanding and increasingly offer interest bearing savings, microloans and other financial products, all delivered digitally and without the need to visit a bank branch or ATM (Shirono et al. 2021).

An overview of some of the most common types of mobile money services from the point of end user is described in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Basic typology of mobile money services

|

Service Type |

Description |

|

Cash‑in/cash‑out |

Deposits and withdrawals of cash via agent network. |

|

P2P transfers |

Peer mobile wallet transactions can either be performed by sending or receiving funds. |

|

International remittances |

P2P transfer to or from a different country. |

|

Merchant and bill payments |

Purchase of goods at physical or online merchants and payments for services, including bills for utilities. |

|

Bulk disbursement |

Transfers made by organisations or governments to distribute salaries or programme/cash transfers. |

|

Mobile money account-to-bank account transfer (and vice versa) |

A direct movement of funds from a mobile money account to a customer’s bank account. The movement of funds can also flow from the bank to the mobile money account. |

|

Savings |

Service linked to a mobile money account which not only stores funds but provides principal security and, sometimes, an interest rate. |

|

Credit |

Mobile phone is used to provide microcredit to customers directly through their mobile money account. |

|

Insurance |

Micro-insurance products integrated with customers’ mobile money accounts and offer compensation guarantees for specified loss or damage. |

Source: GSMA 2025

Prevalence of mobile money services

Mobile payments are the result of a gradual evolution that started in the late 1990s with the introduction and spread of the mobile telephony around the world (FATF 2013). The first mobile money service targeting unbanked customers was established in 2001, but it was the rise of Kenya’s M-PESA after 2007 that brought international attention to the potential of these services (Aron 2017).

Today, a significant volume of financial transactions in some countries is conducted through mobile phones and mobile money services. The latest state of the industry report on mobile money conducted yearly by the GSMA reports that around 108 billion transactions worth over US$1.68 trillion flowed through mobile money accounts in 2024 (GSMA 2025). There were more than 2 billion registered accounts and over half a billion monthly active accounts worldwide (GSMA 2025).

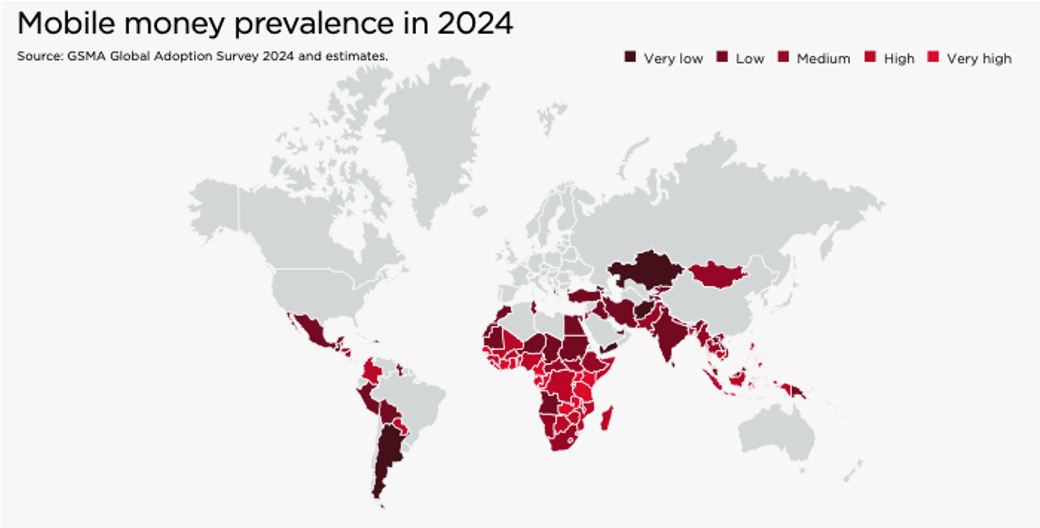

As seen in Figure 4, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is at the heart of mobile money globally, both in scale and economic impact. It is the region with the highest volume and total value of mobile money transactions, with 80 billion transactions of a total value of around US$1.1 trillion in the region in 2024 (GSMA 2025).

While South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific have seen increasing adoption of international remittances, the growth of this transaction type has also been driven primarily by sub-Saharan Africa (GSMA 2025). While international remittances were the fastest-growing transaction category by value, reaching US$34 billion in 2024 globally, over US$100 billion in merchant payments represented the highest-value transaction type within the mobile money ecosystem.

Interestingly, an analysis of M-PESA transaction level data in Kenya shows that while remittances received through an international money transfer constituted only 0.02% of all transactions, their average value was US$85, approximately 60% of the average monthly income in Kenya. This makes remittances significantly larger in value than any other transaction category (Shirono et al. 2021).

Figure 4: Mobile money prevalence in 2024

Source: GSMA 2025

Benefits of mobile money for financial inclusion

Mobile money services are seen to contribute towards financial inclusion as they provide people with access to a broad range of formal financial services (FATF 2013). According to FATF (2025:10), “financial inclusion efforts seek to address the needs of individuals and entities that either have no access to regulated financial services (unserved) or have access, but only in a limited manner (underserved)”.

However, financial inclusion has increasingly been understood as encompassing not just access to financial services but also their use, quality and the user’s financial literacy (FATF 2015).dc2df7548a7d Definitions and conceptual approaches vary in emphasis and acknowledge that exclusion, whether voluntary or involuntary, can arise from a range of individual, structural and systemic factors.89cd9ce604b3

The adoption of mobile money offers underserved populations a convenient and affordable way to conduct secure transfers and payments, while also providing a safe and private means of storing funds. As users become registered and integrated into mobile financial ecosystems, they often gain a pathway to more advanced formal financial services accessed directly through their mobile phones, such as savings accounts, microcredit or insurance products. These services can support small-scale business and livelihood investments, and offer protection against health, agricultural or climate related risks, acting as a stepping stone toward deeper financial inclusion and long-term economic resilience (Aron 2017).

This is especially true in regions with limited coverage by formal banks. Analysis of data from the International Monetary Fund’s Financial Access Survey (FAS) – a supply-side database tracking financial service availability – shows that in many low and middle-income countries, mobile money now provides more access points than traditional banking, with mobile money agents outnumbering both ATMs and bank branches (Shirono et al., 2021). In another recent study, the World Bank (2022) found that in 12 countries (all of which are located in sub-Saharan Africa),219cbefd4b2e adults who have mobile money accounts but no formal bank account now outnumber those with a traditional bank or other regulated financial account.

Despite the contribution of mobile money services towards enhancing financial inclusion, gaps in reaching vulnerable groups of the population remain. About 1.4 billion adults globally (as of 2021) lacked any formal financial account, bank or mobile money (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2022). Furthermore, in sub-Saharan Africa, one-third of mobile money account holders report relying on assistance from a family member or agent to use their account, highlighting persistent barriers related to digital literacy and usability (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2022).

Financial exclusion does not affect all population groups equally. For example, while overall, women are only 7% less likely than men to own a phone, this varies greatly by deployment and by country, with a significant gender gap persisting in many jurisdictions, especially when it comes to mobile money account ownership (GSMA 2024b). Women are underrepresented users of mobile money services due to a number of barriers, including mobile phone ownership, affordability, digital literacy and relevance of products and services to women (GSMA 2021; GSMA 2024b).

ML risks in relation to mobile money services

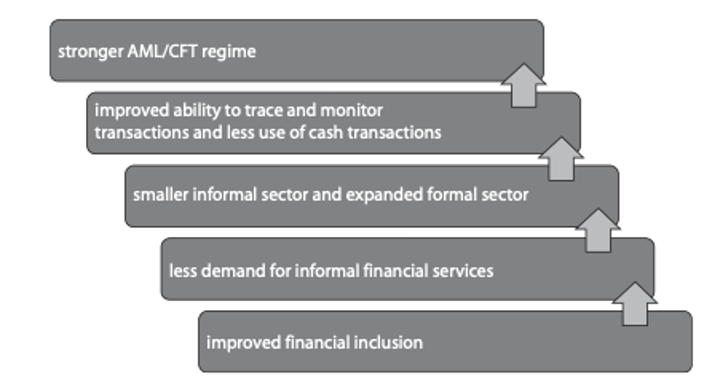

Lopez (2019) has argued that by creating records of financial history, mobile money can reduce the risk of fraud, theft and corruption. Indeed, to the extent that mobile money services contribute to financial inclusion and formalisation, they have the potential to reduce the risk of money laundering and terrorist financing, as depicted in Figure 5.

FATF President Elisa de Anda Madrazo stated that “bringing more people into the formal financial sector is crucial to our fight against financial crime, as it reduces the size of the black and informal markets where criminals and terrorists hide their operations” (FATF 2025b).

Figure 5: How financial inclusion can lead to a stronger AML/CFT regime

Source: Financial Market Integrity Unit, World Bank cited in Chatain et al. 2021: 5

Nonetheless, all financial services are vulnerable to exploitation by criminals to a certain degree, and mobile money systems are no exception.Mobile money services share many of the same money ML/TF vulnerabilities with traditional banking. The nature of mobile money services introduces additional risk factors, including being fast, easily available and often anonymised (GSMA 2015).

There have not been many well documented or high-profile cases of ML or TF conducted via mobile money (GSMA 2015:24)6ec9b822ab29 and, therefore, most analyses of risks are hypothetical or based on typologies used in retail payments and other new payment systems (Solin & Zerzan 2010).

In principle, criminals can exploit mobile money at all stages of a laundering operation, taking advantage of fairly easy-to-open accounts and rapid transaction speeds. Whether during the placement, layering or integration activities, each stage presents unique vulnerabilities that can be exploited to conceal the origin and ownership of illicit funds (Whisker and Lokanan 2019). Solin & Zerzan (2010) differentiate ML and TF risks throughout the different stages of the payment system (loading, transferring, withdrawing), which correspond to the three stages of an ML process:

- Placement/loading: in the placement stage, illicit funds enter the mobile money system, often through cash deposits or mobile wallet top-ups. A key vulnerability is the ability to register multiple or fraudulent accounts, allowing criminals to deposit funds anonymously, via poorly regulated providers. Through the practice of the so-called smurfing or structuring, the funds can be divided into small amounts that are less likely to be detected.

- Layering/transferring: mobile money enables rapid, real-time transfers between accounts to money service businesses or across borders, making it well-suited for layering purposes to obscure the origin of criminal funds. These fast transfers can be difficult to trace and stop, enabled by the anonymity of multiple account registrations and limited transaction monitoring.

- Integration/withdrawing: illicit funds can be reintroduced into the formal economy via mobile money by buying goods or services directly or through further transfers that mask the origin of funds. The speed and anonymity of earlier stages make it difficult for providers and regulators to detect such integration activities. In cases when the funds have been “smurfed” and divided into smaller batches, they can be withdrawn at the same time.

Regarding the types of ML/TF risks connected to mobile money, Chatain et al. (2011) and Solin & Zerzan (2010) recognise four major risk categories: anonymity; elusiveness; rapidity; and poor oversight. Risks of different payment systems can be compared across these categories. For example, mobile money scores lower in risk than cash across all four categories except rapidity.

FATF (2013) highlights several risk factors that can help identify the ML/TF risks linked to NPPS, including mobile money services: non-face-to-face relationships and anonymity; methods of funding; access to cash, geographical reach; and segmentation of services. Segmentation of services includes risks arising from the large number of entities involved in mobile money systems, as well as the use of third parties and agents.

Table 3 outlines key ML/FT risk typologies in mobile money and associated risk factors based on Chatain et al. (2011: 33-37), FATF (2013) and (GSMA 2015: 23-24).

Table 3: Mobile money ML/FT risks and associated risk factors

|

Type of ML/TF risk |

Description of that risk |

Associated risk factors |

|

Non-face-to-face relationships and anonymity |

Mobile money accounts can sometimes be opened with limited face-to-face interaction (whether through agents, digital platforms or directly via the mobile system), increasing the anonymity of users and potential misuse of accounts for illicit purposes. The risk of user anonymity arises particularly during account use or top-up processes. The extent of this risk depends on the effectiveness of AML/CFT safeguards in place, such as customer due diligence procedures and transaction or funding limits (FATF 2013). Moreover, mobile money systems can mask the true identity of senders and recipients due to practices like phone pooling in rural communities or phone delegation in wealthier circles. In both cases, the phone and mobile account are registered to someone other than the actual user, complicating customer profiling and oversight (Chatain et al. 2011). |

Challenges in performing customer due diligence (CDD) in rural or remote areas due to high costs (GSMA 2015). Risk of impersonation or use of synthetic identities where non-face-to-face verification exists or processes are weak (Chatain et al. 2011). Prevalence of informal or poor ID systems in many countries (e.g. lack of national ID) (Chatain et al. 2011). Prepaid mobile users often remain unidentified when registration with providers is not required (Chatain et al. 2011). Use of (third-party) agents who may not rigorously verify identity documents (GSMA 2015). |

|

Methods of funding and access to cash |

Cash based or non-bank options of funding methods of mobile payment services obscure the origin of funds, increasing vulnerability, especially when third parties are involved or proper identification is lacking (FATF 2013). Access to cash through international ATMs or linked services like prepaid cards further heightens ML/TF risks. These tools can enable cross-border withdrawals from anonymously funded accounts, making it difficult to trace the flow of illicit funds (FATF 2013). |

Most mobile money systems rely on agents to accept cash deposits (cash-in), which are then converted to digital value. This creates a risk that illicit cash is introduced into the mobile money system at the placement stage, after which it can be transferred or layered further (Solin & Zerzan 2010). Criminals can deposit the proceeds of crime through “smurfing”: cashing-in multiple small transactions via different agents, obscuring the money trail and avoiding detection (Solin & Zerzan 2010). Weak oversight of agent networks: agents may not ask questions about the source of funds and are sometimes poorly supervised (Solin & Zerzan 2010). Lack of electronic records at the initial deposit point can be an issue (especially if a customer is not registered or agents do not log customer information for a cash-in). |

|

Geographical reach |

Many mobile money platforms offer international remittances and cross-border transactions, which can potentially facilitate both cross-border ML and TF, especially in regions with poor financial oversight. Moreover, high use of mobile remittances without harmonised oversight can create vulnerabilities, though providers should supervise these transactions and impose transaction limits in line with FAFT Recommendation 16 (GSMA 2015). |

If cross-border regulatory coordination and information sharing between countries is limited, criminals can exploit this to move funds internationally via mobile money (Dornbierer 2020). Similarly, risks increase if providers do not keep records of transactions and/or do not make them accessible to the authorities (FATF 2013). However, each transaction can be linked to a telephone number, amount and date and is therefore somewhat traceable (Solin & Zerzan 2010). Stopping rapid mobile money transactions – which happen in real time – is challenging (Chatain et al. 2011), all the more so when it comes to international money transfers involving low-income countries in which fewer resources are available for monitoring and oversight. Stringent restrictions on cross-border transactions might push customers to informal channels (like hawala) are usually subject to even less oversight (Aron 2017). |

|

Segmentation of services - Number of entities involved

|

One of the issues that FATF (2013) raises with regard to the segmentation of services is that numerous entities may participate in delivering mobile payment services (MNOs, banks, third-party providers, agents), with their roles differing based on the specific business model employed. In some cases, a single entity may perform multiple functions while, in others, responsibilities are distributed among various entities. This complexity can pose regulatory challenges in clearly assigning accountability for implementing effective AML/CFT controls. |

When multiple entities are involved, it becomes difficult to determine which entity is accountable for ensuring AML/CFT compliance at each stage and to prevent a potential loss of information about customers and transactions, especially when actors are spread across several countries (FATF 2013). Different entities often fall under different supervisory authorities (e.g. telecom regulators vs. financial supervisors) and MNOs might not be familiar with AML/CFT requirements (FATF 2013). Without effective coordination, each participating entity may have different AML/CFT policies, leading to inconsistent application of CDD or record keeping (FATF 2013). |

|

Segmentation of services - third-party and agent risks |

A second issue that FATF (2013) raises with regard to the segmentation of services is that mobile money services are often run via many independent agents or unaffiliated third parties who can be far removed from bank or mobile phone companies providing mobile money services. While this makes mobile money highly accessible for customers, these intermediaries can be points of vulnerability if the provider cannot ensure adequate training or monitor for compliance, or if they do not share collected customer information with the responsible entity.

|

Incentive structures that reward agents with commissions for mobile money payments (GSMA 2015, Williams 2013) can create perverse incentives to overlook suspicious behaviour or onboarding irregularities. Agents could potentially even abuse their position as a hub for mobile users to operate ML and TF schemes (GSMA 2015). While agents need to adhere to due diligence and reporting processes, close supervision of a vast network of agents is difficult. Therefore, the ultimate responsibility for effective AML/CFT policies, as well as appropriate training and monitoring of agents should lie with the provider of the mobile money services (Chatain et al. 2011). |

Furthermore, mobile money systems involve multiple actors – customers, merchants, employees and agents – each of whom may have an opportunity for ML/TF related crime. A summary of these risks by each actor is outlined below, based on a risk assessment conducted by GSMA (2015: 25-26).

- Customers can pose ML/FT risks when they open an account with fake identity documents, open multiple accounts under different identities or conduct structured transactions to avoid detection. Customers could conduct transfers of funds that are the proceeds of criminal activity.

- Merchants may launder funds by disguising the proceeds of crime as legitimate business transactions since they can receive high volumes of mobile money payments at times. They may also be used by accomplices posing as customers to launder criminal funds through fake transactions.

- Employees of mobile money providers may facilitate or overlook suspicious activity, open false accounts or commit theft of funds. Internal abuse – such as bypassing controls or manipulating records – poses a significant threat if not mitigated through monitoring and internal controls.4bd943fa0641

- Agents who handle cash-in and cash-out transactions are particularly vulnerable to being used to place illicit funds into the system because of their ability to falsify records or omit reporting. Risks include intentional or negligent non‑compliance with due diligence and reporting of suspicious activity, permitting customers to exceed transaction limits, fraudulent registration or intentionally facilitating transactions proceeding from crime.

Addressing the ML/FT risks of mobile money services

This section explores the process of mitigating the ML/TF risks described above. First, it looks at the FATF framework for managing the ML/TF risks associated with mobile money, then it considers which actor is responsible for managing these risks. Next it provides an overview of regulatory approaches to mitigate these risks. Finally, it reflects on the challenges associated with regulating mobile money in developing countries.

FATF and mobile money services

Under the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) AML/CFT regime, non-bank mobile money providers are typically classified as money or value transfer services (MVTS).e4faaa29bd4f As mobile money businesses engage in activities such as money or value transfer services or the issuance and management of payment instruments, they are considered to be financial institutions by FATF (2013; 2016).

The FATF Recommendations prescribe certain compliance obligations that national governments are expected to impose on MVTS providers, including those offering mobile money services. This means that mobile money service providers must implement core AML/CFT controls such as customer identification and verification, record keeping, suspicious transaction monitoring and reporting, and a risk-based approach to mitigation (FATF 2013; FATF 2012-2025).

The industry body GSMA (2015) has issued guidance outlining its interpretation of how the FATF Recommendations apply to mobile payment service providers. While not officially endorsed by the FATF, it is a leading industry initiative aimed at aligning mobile financial services with international AML/CFT standards (FATF 2016:19). Table 4 lists and describes the FATF Recommendations that are most relevant to mobile money according to GSMA (2015).

Table 4: FATF Recommendations most relevant to mobile money

|

FATF Recommendation |

Relevance to mobile money services |

|

Recommendation 1: Assessing risks and applying a risk-based approach |

FATF recommends that all countries and financial institutions should implement a proportional risk-based approach (RBA) to AML and CFT measures. Unduly strict measures that exclude legitimate customers could undermine the effectiveness of an AML/CFT regime by driving financial activity back into unregulated channels, such as hawala systems. This means that a holistic risk assessment evaluating potential risk factors should be undertaken, bearing in mind “the risks, risks mitigants, and functionality” of a particular mobile money service (FATF 2013:18). Recommendation 1 requires financial institutions to conduct their own risk assessments, which can support broader national or sectoral assessments. It complements Recommendation 2, which calls for coordinated, risk-based AML/CFT policies informed by national risk assessments. |

|

Recommendation 10: Customer due diligence |

This recommendation outlines customer due diligence (CDD) obligations, including identification and verification of customer identity, handling non-face-to-face scenarios, understanding the purpose of the business relationship, and ongoing monitoring. It also requires that these measures follow an RBA. Identity verification after establishing the business relationship in non-face-to-face settings is permitted, provided risk mitigation steps, such as transaction limits, are in place. Simplified CDD are allowed in lower-risk scenarios to support financial inclusion. For example, when offering limited financial products to underserved populations, some CDD elements may be inferred from the nature of the account or typical transaction patterns. However, simplified CDD must still be proportionate to risk and cannot be applied where higher risks exist, such as with PEPs, anonymous transactions or high-risk jurisdictions. FATF’s financial inclusion guidance emphasises that monitoring should be aligned with a financial institution’s risk assessment and mitigation strategies. Regulators should respect these determinations if they are well documented and compliant. Technology based models can aid monitoring through thresholds or alerts, which should be periodically reviewed to ensure they remain appropriate. |

|

Recommendation 11: Record keeping |

Financial institutions are required to maintain records of all transactions for at least five years to support investigations and prosecutions when necessary. CDD related records must also be kept for five years. While this applies even to low-risk accounts, the financial inclusion guidance clarifies that no specific format is required for compliance. Institutions are not obligated to retain photocopies of ID documents, only the relevant information provided in them. Record keeping can take various forms, including electronic scans of IDs and registration forms or handwritten notes on identity or transaction documents. Here, flexibility offers space to align with privacy considerations. |

|

Recommendation 14: Money and value transfer services (MVTS) |

Money or value transfer service (MVTS) providers, including mobile money operators offering P2P services, should be licenced or registered with a competent authority and comply with AML/CFT obligations (in line with Recommendation 26). Providers must also register or maintain an up-to-date list of their agents and ensure this information is available to authorities upon request. Agents are considered an extension of the principal financial institution and should be included in the provider’s AML/CFT programme. While regulatory authorities primarily supervise the provider, it is the provider’s responsibility to train, monitor and manage agent compliance. The intensity of agent monitoring should be determined using an RBA, factoring in transaction volumes, services offered, agent’s location and the type of monitoring system in place. |

|

Recommendation 15: New technologies |

Countries and financial institutions are required to assess the ML and TF risks associated with new products, business practices, delivery mechanisms and technologies. Their risk assessment should be conducted before launch, and institutions should regularly review and adapt their risk-based measures as products evolve. While adopting new technologies does not automatically trigger stricter CDD requirements, a dedicated risk assessment is still mandatory. Institutions must consider factors such as transaction types, target customers, intermediaries involved and the complexity of the technology to determine the appropriate level of CDD. |

|

Recommendation 16: Wire transfers |

Providers need to include accurate information about both the originator/sender and the beneficiary/recipient in wire transfers and to ensure that this data travels with the transaction across the entire payment chain. Providers must also detect transfers missing this information and freeze accounts if required by the UN Security Council rules, although there are nuances to the application. For qualifying cross-border transfers above a set threshold, only the sender’s information must be verified by the ordering institution, while the receiving institution verifies the recipient. For domestic transfers, simplified sender identification may be permitted if traceability is ensured. Additionally, countries may set a threshold of up to USD/EUR1,000, below which verification of both parties may not be required, unless there is suspicion of ML or TF. |

|

Recommendation 18: Internal controls and foreign branches and subsidiaries |

Financial institutions should establish AML/CFT programmes, and financial groups should implement group-wide frameworks that include information sharing procedures and policies. These programmes must cover internal policies and controls, compliance management, employee screening, ongoing training and an independent audit function. Institutions should also develop robust internal controls for monitoring and reporting suspicious activity and fostering a culture of compliance. The scope and scale of these measures should correspond to the institution’s risk exposure and its business size. |

|

Recommendation 20: Reporting of suspicious transactions |

Financial institutions are required to promptly report any suspicions of criminal activity or TF to the country’s financial intelligence unit (FIU). Together with the Recommendation 11 on record keeping requirements, this obligation falls under measures that are non-risk-based, meaning they are always mandatory (FATF 2025). Nevertheless, applying an RBA to individual financial services still helps institutions allocate resources more effectively. Financial institutions must establish internal monitoring systems capable of detecting unusual or suspicious behaviour. |

|

Recommendation 26: Regulation and supervision of financial institutions |

Financial institutions offering money or value transfer services should be licenced or registered and subject to effective monitoring systems to ensure compliance with national AML/CFT regulations. Countries using an RBA to supervision may adjust the frequency and depth of oversight based on the level of ML/TF risk and the adequacy of the institution’s internal controls and procedures. |

|

Recommendation 34: Guidance and feedback |

Competent authorities should issue guidance and provide feedback to help financial institutions implement national AML/CFT measures, especially for identifying and reporting suspicious transactions. According to the financial inclusion guidance, effective public–private information exchange is key to aligning public and private sector efforts and countering financial crime while supporting financial inclusion. |

Source: GSMA 2015

Determining the actor subject to AML/CFT obligations

The actor responsible for AML/CFT obligations depends on the structure of the mobile payment model. In a bank-centric model, the bank managing customer funds and relationships is the financial institution subject to AML/CFT rules. In an MNO-centric model, the MNO or its subsidiary acts as the financial institution, offering the service, managing customer relationships, holding the funds and bearing AML/CFT responsibilities accordingly (FATF 2013).

When multiple entities are involved in the provision of the mobile money service and the primary provider is unclear, countries should assess certain factors to identify the most appropriate entity to designate as the appropriate provider(s) (FATF 2013):

- the entity that has visibility and management of the mobile money

- the entity that maintains relationships with customers

- the entity that accepts the funds from the customer

- the entity against which the customer has a claim for those funds

Another way to determine which entity is responsible for ensuring compliance with AML/CFT measures is the rule of the account provider. This rule “identifies the provider of the account as the party best suited to verify AML/CFT practices applied at the other stages of the money flow” (Chatain et al. 2011: 10).

Because the account provider is the entity that maintains the account records, they are best positioned to monitor customer activity and ensure compliance across the mobile money value chain, whether it is an MNO, a bank or another entity. However, since account management can be outsourced, regulators must clearly identify which entity holds ultimate legal accountability for compliance breaches (Chatain et al. 2011).

Mobile money providers often rely on a network of distributors or agents who interact directly with customers at the point of sale. These agents may carry out AML/CFT measures, such as customer due diligence (CDD), on behalf of the provider, particularly when loading funds into accounts or issuing mobile money. In such cases, the agent is acting on behalf of the mobile money provider and is considered its representative (FATF 2013: 35).

Regulatory approaches to mitigate AML/CFT risks of mobile money

Before developing appropriate risk-based AML/CFT measures, all actors involved in the regulatory action should first understand the distinct features of mobile money services, including their specific advantages, risks, and the safeguards needed to address those risks. GSMA (2015)23c980fedd4a advises the actors to:

- familiarise themselves with the FATF Recommendations and relevant legislation

- document the specific country risks and risks posed by different customer groups

- study the national risk assessment

- undertake a risk assessment with a focus on ML/TF risks of mobile money

- assess the risk factors and mitigation measures

Guided by the FATF’s international standards, governments, regulators and mobile money providers have adopted various measures to reduce the ML/TF risks of mobile money. Table 5 below summarises such measures and regulatory approaches, including a rationale for these approaches, together with potential unintended consequences associated with their application.

Table 5: Regulatory approaches to mitigate ML/TF risks of mobile money

|

Regulatory approach |

Rationale for approach |

Potential unintended consequences |

|

Licensing and registration In line with the FATF Recommendation 26,* countries should establish licensing and registration procedures for mobile money providers to ensure they are authorised to provide offered services. The type of licence granted to mobile operators affects their role in mobile money and the extent of their AML/CFT responsibilities. Licensing approaches generally fall into two categories: provider-based and service-based licences (Chatain et al. 2011). |

In the provider-based model, only existing financial institutions can issue mobile money. MNOs must partner with a bank, which bears most regulatory and AML/CFT responsibilities. This model, used in countries like Brazil and India, limits non-bank participation and may restrict financial inclusion. The service-based model focuses on the service rather than the provider, allowing both banks and non-banks (like MNOs) to issue mobile money if licenced. This approach has gained popularity due to its positive impact on innovation and financial inclusion. While prudential requirements are lighter than for banks, full AML/CFT compliance remains necessary (Chatain et al. 2011). |

The provider-based model, which limits mobile money issuance to banks and requires MNOs to act only as partners, is seen as stringent and not proportionate to the lower risk of mobile money. This may deter non-bank innovation and restrict access for underserved populations. By contrast, while the service-based model encourages broader participation and fosters innovation, it may introduce regulatory challenges if licensing and oversight mechanisms are not adequate (Chatain et al. 2011). |

|

Supervision is also mandated by FATF Recommendation 26. The two main supervisory authorities for mobile money are central banks (or financial regulators) and telecommunications authorities. However, some countries entrusted supervision to other institutions, such as the FIU in Spain (Chatain et al. 2011). Countries should require providers to include agents in their AML/CFT programmes and actively monitor their compliance. The provider remains legally responsible for meeting AML/CFT obligations and is accountable for agents’ actions (FATF 2013:31). |

Many countries have established oversight mechanisms for mobile money by assigning supervisory authority to the central bank or financial regulator rather than the telecommunications authority. This approach is seen as more effective since financial supervisors are better equipped to assess risk, enforce AML/CFT compliance and understand financial operations, even when services are delivered by telecoms or third-party providers. To strengthen oversight, some countries establish dedicated units within central banks to supervise non-bank financial providers. Others require telecoms companies to set up separate entities for their financial services to avoid regulatory overlap. These mechanisms help clarify responsibilities and improve supervision (Chatain et al. 2011). |

According to research, while central banks may lack the technical expertise to oversee mobile money systems, communications authorities at times feel unprepared to manage financial risks. Both have shown reluctance to take full supervisory responsibility, leading to regulatory gaps and uncertainty. Chatain et al. (2011) do not recommend the FIU model, as FIUs may lack experience and resources for supervising MNOs. Moreover, legal barriers may limit the sharing of information such as suspicious transaction reports (STRs) and lead to inconsistent compliance approaches (Chatain et al. 2011). |

|

Tiered or simplified KYC requirements & (simplified) CDD** Where ML/TF risks are low, financial institutions may apply simplified CDD, but never fully skip it. These measures must still meet basic CDD standards, though the level of detail and frequency can be reduced (FATF 2013). This means adopting tiered customer due diligence where small-value transactions have low ID thresholds, while higher value or more risky transactions trigger comprehensive ID protocols (GSMA 2015). FATF (2025a: 63) observes that some countries have developed specific legal and regulatory frameworks to promote mobile money services by adopting a tiered approach to CDD. These foresee that simplified CDD protocols could apply “when the products or service are accessed in specific circumstances, for example, face-to-face via a non-bank agent or through a mobile phone or an e-money issuer”. In addition, these simplified CDD measures are backed in some countries by regulations that impose ID requirements for people registering a SIM card (FATF 2025a: 63). |

Enables inclusion by allowing those with no formal ID or proof of address to open basic accounts, thereby bringing more users into regulated channels (GSMA 2015: 16). Several SSA countries accept alternative IDs (voter card, letter from local officials, etc.) to allow registration for mobile money accounts and expand mobile money account ownership (GSMA 2015: 43) In comparison with cash, mobile money provides traceability, with every transaction being recorded via the sender’s mobile number, amount, receiver’s mobile number, date (GSMA 2015). Tracing transactions and money flows through account-based mobile money services, rather than over-the-counter transactions, helps mitigate risk (GSMA 2015). Mobile money providers can build customer profiles using data collected during registration and through ongoing activity, such as income, transaction history and service use. These profiles help detect unusual or suspicious transaction patterns (Chatain et al. 2011: 51) and could be requested by regulators as part of a CDD process. |

Regulators must carefully determine the type of identification that should be provided when registering an account as well as the extent of due diligence required. If the standards are set too high, this might create an obstacle for financial inclusion and for people to join the formal financial system (GSMA 2015).*** On the other hand, if the rules are too lax, criminals may exploit the opportunity of a simple account registration. Similarly, given the high-volume, low-value nature of mobile money transactions, if CDD requirements are not kept simple and cost-effective this might negatively affect the viability of these services (GSMA 2015). |

|

Transaction and balance limits Regulators can choose to impose limits on account balances, single transaction amounts (including withdrawals), the frequency of transactions, cumulative transaction values over set periods (daily, weekly, monthly or yearly), geographical or purchasing limitations or a combination of these (FATF 2013). The industry body GSMA states that mobile money service providers must place “limits on transactions and balances using mechanisms that provide close oversight of the system” (GSMA 2015:30). |

Institutions can design tiered services with varying restrictions to keep lower-risk products eligible for simplified CDD, applying stronger AML/CFT measures as functionality and risk grow (FATF 2013). Transaction limits can also force larger transfers into formal banking channels. Service providers’ monitoring systems can be designed to flag high frequency or high total-volume activity below these limits (Solin & Zerzan 2010). This can act as a safeguard against the risk of structuring discussed in Table 3, provided systems are sophisticated enough to aggregate activity. |

If limits are set arbitrarily low, users might revert to cash or less regulated methods (e.g. hawala) for convenience, which could in turn increase overall opacity in the system (FATF 2013). Strict limits might also constrain legitimate use cases (e.g., small businesses needing to make slightly larger transfers or with higher frequency); therefore, some mobile money providers offer special accounts for corporate users with higher transaction limits (Aron 2017). Criminals may adapt by opening multiple accounts or using networks of accomplices (smurfing) to circumvent limits, which means limits alone are not sufficient (GSMA 2015). |

|

Record keeping, monitoring and reporting obligations To fulfil the requirement to implement automated transaction monitoring systems and report suspicious transactions to the financial intelligence unit, mobile money providers have developed electronic systems to identify and monitor suspicious transactions (GSMA 2015). A survey conducted by GSMA (2015) showed that most surveyed providers monitor staff, agents and customers for AML/CFT compliance, tracking transaction patterns and conducting on-site checks, sometimes with mystery shoppers. |

Transaction monitoring systems aid the identification of suspicious activity or suspicious trends in activity, aligning mobile money providers with global standards like FATF (GSMA 2015). |

Implementing robust monitoring technology can be costly and complex for telecom companies, especially smaller providers, possibly leading smaller providers to shut down (GSMA 2024b) or to higher fees for users. Emulating SAR (suspicious activity report) requirements from developed countries can reduce the attractiveness of mobile money for low-income users, e.g., if providers over-report (Goldby 2013). In some countries, government surveillance of mobile money platforms is more aimed at tracking operators’ revenues for tax reasons than it is in preventing financial crime (Martin 2019). |

|

Agent regulation, monitoring and training Imposing licensing requirements or background checks for mobile money agents, requiring providers to train agents in KYC and AML red flags, and conducting agent profiling and audits (GSMA 2015). |

Vetting and registering agents helps ensure a basic level of professionalism and accountability, which is important for providers due to their liability for AML/CFT screening conducted by agents (GSMA 2015). |

In theory, stricter agent rules could reduce the number of agents, especially in remote areas if the compliance burden or costs (e.g., licensing fees) are too high. This could reduce access for some communities, or reliance on informal brokers or third parties who are unregulated. |

Regulatory challenges of mobile money in low-income countries

While mobile money has become popular in low-income countries due to its accessibility compared to formal banking, many people still face barriers such as a lack of formal identification or limited financial literacy. Due to these factors, as well as the lack of financial and technical resources needed to effectively supervise mobile money services, regulators in these jurisdictions often face challenges in designing cost-effective KYC and CDD systems. These constraints can leave gaps in AML/CFT oversight, making mobile money systems more vulnerable to misuse.

The complex interface between telecom and banking sectors in delivering mobile money services can leave regulatory responsibility unclear or fragmented, creating high demands for the already strained regulatory capacity to guide the sector effectively. However, many regulators in low-income countries face limited capacity and expertise to oversee these innovative services, which can lead to regulatory gaps and uncertainty (Chatain et al. 2011). Moreover, the one-size-fits all approach outlined in some FATF Recommendations, such as the strict uniform requirements for reporting systems for suspicious activities, may be impractical in low-income countries (Goldby 2013).

Regulatory oversight is further weakened by inadequate technological infrastructure, especially in rural areas where unreliable networks and electricity shortages not only limit service availability but also make conducting CDD prohibitively costly, hampering the supervision of mobile money services (GSMA 2015; Carbonell and Escudero 2025). While mobile payment systems generate a digital record of each transaction, allowing for traceability and investigation by authorities (Dornbierer, 2020), many institutions might lack the sufficient expertise, resources or cross-agency collaboration to effectively analyse the data.

Recourse constraints might also make it challenging for many service providers to fully comply with the desired AML/CFT measures, such as the creation of automatic monitoring and flagging systems or sufficient training and oversight of agents who may be at risk of not consistently following KYC procedures or identifying suspicious activities (Solin & Zerzan, 2010). The criteria to which service providers must adhere to obtain a certification by GSMA, which include the establishment of a dedicated compliance unit and a money laundering reporting officer role (GSMA 2019: 13-18), might also pose a challenge for some.

Practices such as phone pooling in low-income and rural communities may mask the true identity of users of mobile money services, since the phone and its mobile account are registered to someone other than the actual user, complicating customer profiling and oversight (Chatain et al. 2011). Furthermore, a knowledge barrier due to language differences or limited financial and digital literacy among both consumers and agents, can reduce the effectiveness of AML controls, create gaps in understanding the services, lead to consumer security concerns (Mogaji & Nguyen 2022) and ultimately also exposure to fraud and misuse.

Lastly, one of the most critical issues is the lack of formal identification of substantial portion of the population,c539539399a0 which complicates the implementation of KYC requirements and increases the ML risks (Solin & Zerzan 2011). In low-income countries where official ID documentation exists, substantial parts of the population often remain unidentified, while some countries lack formal ID systems altogether.abda077314b9

Some regulators permit alternative accredited forms of identification of ID cards, such as voter cards, student cards or even letters from village chiefs or community leaders. The FATF financial inclusion guidance provides examples of such IDs but warns of the risks of fraud and misuse. Typically, these alternative IDs are restricted to specific transaction types and are subject to thresholds and limits (GSMA 2015).

In addition to identification requirements for mobile money accounts, many jurisdictions might require citizens to register their SIM cards due to ML and national security concerns. When this process is not aligned with mobile money account registration and a different set of documents are required to identify users, this might pose an additional barrier to financial inclusion (GSMA 2021), as has reportedly been the case in South Africa.9059c86a9b63

Good practices to strengthen AML/CFT controls on mobile money services

This section summarises some examples of good practices to strengthen AML/CFT controls on mobile money services across sub-Saharan Africa. It first introduces the actions taken by regulators and then covers initiatives by providers and industry bodies.

Actions taken by regulators

Tiered or simplified KYC requirements

Ghana: in 2015, the Central Bank of Ghana issued guidelines to regulate the issuance and operation of electronic money, allowing non-bank entities to enter the market. Customer accounts are classified into three main tiers under a risk-based approach, each with specific KYC and CDD requirements, with level 1 accounts requiring minimal documentation and being subject to low transaction and balance limits (FATF 2025: 91).cb3f2f5b38bc

Transaction and balance limits

Ghana: in the Ghanaian system, the lowest tier accounts are subject to low transaction and balance limits – US$72 as a daily limit, US$716 monthly and a US$239 balance; while enhanced KYC accounts permit US$1,194 daily, $11,936 monthly and balances up to $4,774. Moreover, there are two tiers of over-the-counter (OTC) services for those who do not have a mobile money account. For customers without ID, the limits are the most restrictive. With ID, OTC users can transact up to US$477 daily and US$4,774 monthly, similar to level 2 account holders (GSMA 2015: 43).

Monitoring & reporting obligations

Tanzania became the first country to deploy a mobile money monitoring system (M3) for regulators in 2016. The platform enables the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) to track mobile money transactions and ensure regulatory compliance. While praised by the national audit office for improving oversight, concerns have been raised about “scope creep” as the system may also be used to assess tax liabilities, beyond its original regulatory purpose (Martin 2019).

Kenya’s Safaricom uses Neural Technologies’ Minotaur software to manage AML/CFT risks by facilitating KYC through watchlist checks and ID verification, monitoring all user activity (customers, agents, staff) for suspicious patterns and building behaviour profiles to detect anomalies like smurfing or high-risk transfers. It validates transaction locations to spot irregularities, tracks agents’ operations and monitors internal employee activity to ensure authorised system use (GSMA 2015).

Agent regulation, monitoring and training

Ghana: the Bank of Ghana issued agent guidelines to support the structured development of agent networks, including recommendations on recruitment and management of agents, agent eligibility and due diligence, or reporting and sanctions (Bank of Ghana 2016).

Nigeria: Similarly, the Central Bank of Nigeria issued detailed regulations in 2013 outlining eligibility criteria, responsibilities and supervisory expectations for agents and their relationships with financial institutions to provide minimum standards and enhance financial inclusion (Central Bank Nigeria 2013).

Supervision and enforcement actions

Liberia: in Liberia, regulatory authorities have taken enforcement action against Lonestar Cell MTN Mobile Money Inc. for repeated violations of the Central Bank of Liberia’s mobile money regulations. The company was fined millions of Liberian dollars for persistent non-compliance and for failing to meet minimum local corporate governance standards. The South African telecom company has been fined in a number of other countries across SSA (FrontPage Africa 2024).

Uganda: in recent years, Uganda’s financial intelligence authority has imposed fines on several telecom companies for non-compliance with AML regulations related to mobile money services. Penalties have reached up to UGX500 million (approx. US$132,000) due to inadequate transaction monitoring and failure to report suspicious activities (Arctic Intelligence 2024).

Initiatives by service providers and industry bodies

Strengthening AML systems at mobile money service providers (detection, monitoring, reporting, training)

Methods to identify ML/TF:GSMA (2015: 25-26) identifies a number of strategies to detect potential money laundering or fraud. This includes on-site visits by service providers to determine whether licenced mobile money agents comply with their ML/TF obligations, as well as “mystery shopping” tactics. Furthermore, service providers (and supervisors) could examine a sample of records kept by agents to look for evidence of:

- fraudulent ID documents

- multiple SIM ownership

- numerous frequent transactions just below the limit

- presence of customers on watchlists or sanctions databases

- mismatched account balances

- personal relationships between customers/merchants and agents that could point to risks of collusion

- transfers to high-risk locations

GSMA mobile money certification: a global initiative independently assessing the ability of mobile money service providers to deliver secure mobile money services, protect the rights of consumers and to prevent ML and FT. Principle 2 in the GSMA certification guidance lists criteria to which service providers must adhere in the area of AML/CFT and fraud (GSMA 2019). These include:

- dedicated compliance unit

- appointment of a money laundering reporting officer

- customer due diligence

- monitoring and reporting of suspicious activities

- AML and CFT training

- fraud management

Guidance for mobile money service providers on these aspects of AML/CFT compliance is provided by GSMA (2024d: 14-18). Several providers across sub-Saharan Africa, including Kenya’s Safaricom and Tanzania’s Vodacom, have been certified by GSMA.10405b52c8ec

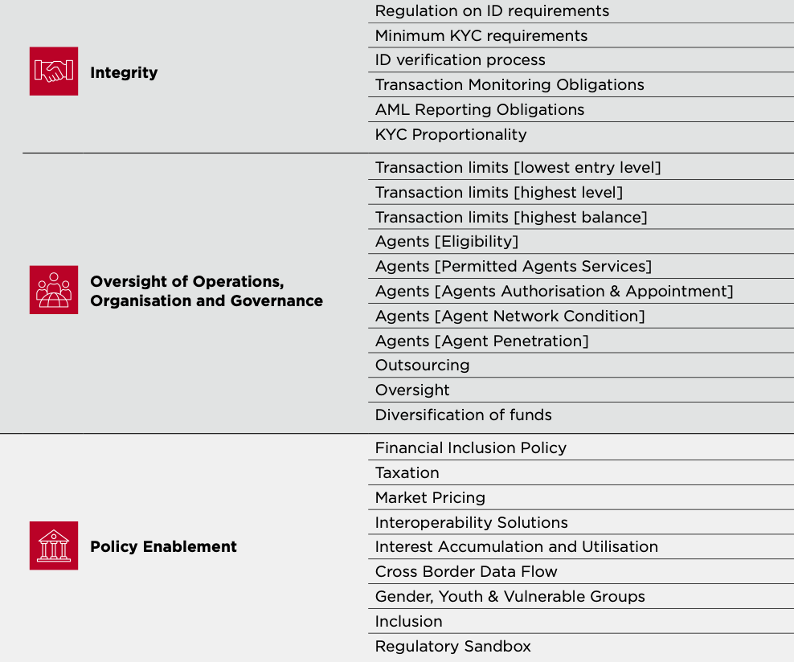

GSMA mobile money regulatory index: also developed by GSMA, the index provides an assessment of how well regulatory frameworks foster sustainable mobile money ecosystems. The index aims to help policymakers and industry stakeholders identify strengths and gaps in country level digital finance regulations as it covers several relevant indicators, including transaction limits and agent networks, KYC, transparency and disclosure, and policy enablers (including a financial inclusion strategy) (GSMA 2024a).The most relevant indicators are highlighted in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Select Indicators from the Mobile Money Regulatory Index 2022

Source: GSMA 2024a

Balancing AML and financial inclusion in mobile money services

The mobile money sector is an emerging industry and its regulation is still evolving. To respond to AML and CFT concerns associated with these services, many countries have introduced specific legislation, largely within the past decade. A key objective in such regulation has been balancing the objectives of financial inclusion and innovation against those of financial integrity and AML measures (Goldby 2013; GSMA 2015; FATF 2025; Kersop & Du Toit 2015a; Kersop & Du Toit 2015b). FATF (2013) guidance explicitly notes that financial inclusion and AML/CFT objectives can be complementary if measures are calibrated correctly. In fact, recent publications by FATF (2025) recognise that overly cautious, disproportionate AML/CFT measures can exclude or underserve legitimate users by limiting or raising the cost of access to regulated financial services.

On the one hand, countries need to assess the ML and FT risks of mobile money and take steps to mitigate them in line with their country’s realities and in line with the FATF Recommendations (GSMA 2015). On the other hand, as over-regulation might lead to financial exclusion, ultimately hampering financial integrity, it is important to mitigate the risks of ML and FT in mobile money services in a way that does not impose unnecessary burdens on the stakeholders and actors involved (FATF 2025; Kersop & Du Toit 2015a).

As Chatain et al. (2011: 32) highlight: “low amounts of money, traceability, and the monitoring features of m[obile] money programs could make m[obile] money far less risky than other methods of payment, particularly cash”.

Based on the literature reviewed, the following section outlines several recommendations for countries and regulators to foster proportionate AML/CFT regulatory approaches to mobile money. A more comprehensive, if slightly outdated, list of recommendations is provided by Chatain et al. (2011: 107-135) for both regulators and mobile money service providers.

Conduct a national risk assessment

To develop proportionate AML/CFT regulatory approaches and establish a national standard for lower and higher risk scenarios in the mobile money industry, ideally a sector-specific risk assessment would be conducted (FATF 2013). This would take account of the sector’s strengths, vulnerabilities and risks (GSMA 2015). This can be used to inform the design of simplified KYC and CDD measures.

The World Bank has recently developed a financial inclusion product risk assessment moduledesigned for the appraisal of ML/TF risks associated with financial inclusion products. As part of the risk assessment process, workshops convene “experts from the financial intelligence unit, the financial sector supervision department, the financial inclusion department or group (usually part of the central bank), telecom authorities (with regulatory responsibilities for mobile money), and representatives from the private sector” (FATF 2025a: 117-119). The objective is to determine whether CDD requirements can be simplified to reduce financial exclusion. In Nigeria, Tanzania and Zambia the exercise concluded that the regulatory framework required revision to facilitate simplified CDD for certain mobile money products (FATF 2025a: 119).

Adopt a risk-based and proportionate framework for mobile money

Once a risk assessment has been conducted, there is broad consensus in the literature that balancing financial inclusion and AML compliance requires a regulatory approach guided by the criteria of proportionality (see Chatain et al. 2011:143-154). In practice, this means that risk mitigation procedures should be tailored to the level of risk associated with the specific product or service, following a risk assessment (FATF 2013). FATF (2025: 34) states that, in lower-risk scenarios, countries are “required to not only enable but also advocate for the adoption of simplified measures”.

There is agreement in the literature that progressively more stringent approaches can be useful in this regard, such as the tiered KYC and CDD measures adopted in several countries. This tiered structure balances financial inclusion with AML/CFT risk controls by linking higher transaction and balance ceilings to stronger customer identification and monitoring (GSMA 2015). Moreover, some authors argue that regulatory areas that currently do no allow for a risk-based approach, such as SAR reporting obligations, pose an issue for low-income countries and should be reconsidered (Goldby 2013).8c00ba260abd

Strengthen regulatory efforts and supervision of mobile money services

In general, supervision of mobile money remains limited, with many regulators lacking experience, resources and clarity on AML/CFT issues. For example, a GSMA (2024c) survey showed that 82% of respondents perceived regulations as slowing down technological advancements and failing to address the risks of rapidly evolving mobile money payments systems. Uncertainty also exists over whether financial examiners can access sensitive data like SMS messages, raising concerns about privacy and regulatory scope (Chatain et al. 2011). Therefore, authorities could strengthen their regulatory and supervisory capacity to follow the rapidly evolving mobile money ecosystem, including its risks.

Harness technology along the risk mitigation process

Technology could be leveraged to strengthen AML/CFT safeguards in mobile money systems by enhancing identification, verification, monitoring and fraud detection. Advanced tools such as facial, voice and fingerprint recognition can significantly reduce anonymity risks by uniquely linking accounts to individuals, especially in non-face-to-face transactions. Predictive modelling and AI-driven systems have demonstrated their potential in uncovering smurfing fraud chains, enabling mobile money service providers to detect suspicious transaction patterns and block high-risk accounts or mobile numbers in real time (Whisker & Lokanan 2019).

Leverage information from mobile money transactions for investigations

Despite some challenges that might exist with full identification of mobile money users, mobile money accounts are not anonymous. The accounts and their transactions should be traceable due to a digital footprint in the form of the date of the transaction, telephone number, value of money sent and sometimes even a location (Solin & Zerzan 2010). These recorded transactions might show patterns and reveal the identities of the users behind them (de Koker 2009a in Chatain et al. 2011).

However, this data is only traceable and usable for monitoring or investigation if authorities have access to it and are able to use it for these purposes. This means they require resources for technology and personnel, with appropriate regulatory processes to follow. A more systematic, targeted focus on mobile payments “could help strengthen a country’s resilience to money laundering and terrorist financing” (Dornbierer 2020).

- FATF refers to mobile money also as “mobile payments” (FATF 2013).

- Kenya’s M-PESA systems is run by retail agents who use their own cash and M-PESA e-money balances to serve customer transactions, operating within standard account limits and through wholesale agents, such as banks or large merchants, who hold higher e-money limits and provide liquidity support to retail agents (Aron 2018).

- Technology to facilitate mobile money payments varies and can include “text messaging, mobile Internet access, near field communication (NFC), programmed subscriber identity module (SIM) cards and unstructured supplementary service data (USSD)” (FATF 2013:7).

- Some approaches stress inclusion, while others focus on exclusion, particularly of vulnerable groups. Access may be tiered, and exclusion can be voluntary (e.g. due to cultural norms or reliance on intermediaries) or involuntary, stemming from income constraints, lack of collateral, perceived credit risk or discrimination. Broader barriers include weak infrastructure, poor regulation, lack of credit data, low consumer awareness and uncompetitive markets (Aron 2017). Further systemic barriers include armed conflict, extreme poverty and natural disasters (Goldby 2013).

- Nearly 20 years ago, Beck et al. (2008) defined financial inclusion as a state in which everyone can access a range of quality financial services at affordable prices in a convenient manner. Nowadays, Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) defines financial inclusion as a state when “all people and businesses have access to — and are empowered to use — affordable, responsible financial services that meet their needs. These services include payments, savings, credit and insurance” (CGAP 2025, para. 1).

- These 12 countries were Benin, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Guinea, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- Many published cases of criminal conduct linked to mobile money are the accounts of fraudulent behaviour, false identification and misuse of existing accounts. See Digital Frontiers Institute (n.d.) for more on abuse of mobile money services in Bangladesh, and Dornbierer (2016) in Uganda.

- For example, in Uganda, in 2013, approximately US$850,000 was stolen by MNO staff and agents via seven transactions and funnelled through 138 accounts before being withdrawn. In another case, employees of the same MNO embezzled US$2.4 billion over six months by exploiting weak know-your-customer KYC and IT system controls (Dornbierer 2016).

- According to the FATF glossary, “Money or value transfer services (MVTS) refers to financial services that involve the acceptance of cash, cheques, other monetary instruments or other stores of value and the payment of a corresponding sum in cash or other form to a beneficiary by means of a communication, message, transfer, or through a clearing network to which the MVTS provider belongs.” GSMA (2015: 29) notes that “a mobile money provider would not be classified as an MVTS provider if it is simply providing bill payment services and not providing P2P services”.

- See GSMA (2015:19-20) for a proposed step by step guide for both regulators and providers to streamline the workflow of a risk-based assessment process.

- For example, when Tanzania first distributed ID cards to a portion of its registered residents in 2016, concerns emerged about the quality of the cards. A particular concern was illegible signatures, which led many financial service providers to reject them as valid identification (Boshe 2021).

- While ID systems now rely on digital data in more than 90% of countries, it has been estimated that globally around 850 million people still lack official proof of their identity (as of 2021) (Metz, Casher and Clark 2024).

- South Africa illustrates the challenges of aligning AML/CFT requirements with SIM card registration rules. While the country allows flexible, risk-based processes for mobile money KYC (including non-face-to-face verification), these measures conflict with the stricter face-to-face SIM card registration requirements introduced in 2009. The duplication of requirements between these two processes and two sets of legislation is seen as undermining the flexibility originally intended to promote financial inclusion, adding costs and inconvenience for customers and providers (Chatain et al. 2011: 55).

- In the words of Elly Ohene-Adu, from the Bank of Ghana (GSMA 2015: 42): “In a country with limitations on the type and quality of IDs and a large rural sector with no street or house markings, regulators have to be creative in the agenda on financial inclusion. Ghana’s innovative 3-tiered KYC system is to ensure that everyone in the financial pyramid and certainly, at the bottom of the pyramid, can be roped into the formal financial system and can transact under a risk-based regime structured around maximum balances, daily and monthly transaction levels.”

- For a list of 15 certified providers as of August 2025, see: https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/mobile-money/certification/

- According to Goldby (2013) the FATF should consider moving away from a one-size-fits-all suspicious activity reporting model and consider alternatives suited to local contexts. In some cases, strict SAR requirements may be impractical, and streamlined reporting – accepting multiple formats and minimising bureaucracy – may be more effective. Where reliable CDD and record-keeping are in place, SARs could be limited to cases of clear suspicion, with law enforcement given conditional access to service providers’ records for investigations, avoiding unnecessary filings.