Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption issues and anti-corruption measures in Vietnam, with a focus on the sectors related to its nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Background

Vietnam is a lower middle-income country situated in Southeast Asia, bordering the Pacific Ocean on one side and Cambodia and Laos on the other (World Bank 2025). It was under French colonial rule for six decades, during which its natural resources were heavily exploited, and its power centralised, with the French ruling on all levels of the administration and economy (Duong 2015:23). While Vietnam gained independence in 1945, until 1975 it experienced the American war which significantly damaged its economy (Duong 2015:23).

Today, Vietnam is a socialist republic with a one-party system, with its political power structure divided into the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), the government and the parliament, known as the national assembly (Hanns Seidel Stiftung 2021). It has undergone a recent shift with the death of the previous CPV general secretary, Nguyễn Phú Trọng, who passed away in 2024. After this, authorities restored a power sharing agreement that divided duties between the CPV general secretary, the president, the prime minister and the national assembly head, effectively diluting the successive CPV general secretary’s rule (Freedom House 2025). The national assembly is elected by citizens every five years, and, recently, there have been indications that the national assembly has been able to operate more independently from the executive branch (Hanns Seidel Stiftung 2021).

International pressures have also had an influence on Vietnam, particularly due to its deepening international trade relationships, which have required more political openness and regulatory compliance (Cuong 2024:19; EAF 2019). For example, Vietnam now participates in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and is a close trading partner of the European Union (EU), signing a partnership and cooperation agreement in 2012 with a free trade agreement that came into force in 2020 (BMZ n.d.).

Despite these reforms, power has remained relatively centralised under the CPV, despite economic liberalisation in recent decades (Cuong 2024:17). There is reportedly little to no organised opposition to the CPV, nor is there an independent judiciary (BMZ n.d.). Control by the government and the party are also notable during national assembly elections, and civic participation is limited (Hanns Seidel Stiftung 2021; BMZ n.d.; Freedom House 2025).

Anti-corruption has been a prominent policy issue in the country in recent years. There have been some shifts towards stronger governance systems in the country, which have included enhanced local governance, upgrades to legal frameworks, anti-corruption measures and some improvements in electoral practices (Cuong 2024:17). Improvements to the anti-corruption legislation has led to an increase in prosecutions for corruption within the political system itself.

The well-known national anti-corruption campaign, which was initiated by general secretary Trong, is often referred to as the “blazing furnace” and has aimed to raise awareness of corruption in the country (Pham 2024). In 2023, it had led to 24,162 people being disciplined for receiving bribes or incorrectly declaring their income (Pham 2024). However, the context within which this campaign has been conducted is complex. While the government has carried out this widespread anti-corruption campaign and prosecuted numerous public officials, some have argued that this has partly been as a means for top leaders to purge enemies (Freedom House 2025). Some suggest that the vertical political structure still lends itself heavily to corruption, given that many accountability institutions are under the direct supervision of the CPV (Duong 2015:23).

Despite crackdowns and high-level political commitments, the evidence indicates that corruption remains to be a continuing issue in Vietnam, impeding the country’s development. The “blazing furnace” on corruption has, according to some, led to several unintended consequences (Tatarski 2022). While the country possesses substantial potential for economic growth, particularly in sectors related to the green energy transition and climate change mitigation measures, corruption remains a complex and persistent challenge. This Helpdesk Answer provides an overview of the current corruption and anti-corruption issues in the country as well as how these risks affect its green energy transition and other climate change mitigation initiatives.

Overview of corruption in Vietnam

The extent of corruption

Table 1: Vietnam’s performance on selected governance indicators

|

Worldwide Governance Indicators (World Bank) |

CPI (TI) |

GCB (TI) |

Rule of law (WJP) |

UNCAC |

Freedom House |

||

|

Control of Corruption (percentile rank, 100 being the highest) |

Rule of Law (percentile rank, 100 being the highest) |

Voice and Accountability (percentile rank, 100 being the highest) |

Rank (of 180) / Score (of 100) |

Bribery rate (% of citizens over past 12 months) |

Rank (of 142) / Score (0 [worst] to 1 [best]) |

Status |

Score (of 100) |

|

38.39 (2013)

35.24 (2018)

38.63 (2023) |

39.44 (2013)

52.38 (2018)

50.47 (2023) |

10.80 (2013)

8.25 (2018)

15.20 (2023) |

88 / 180 (2024)

40/100 (2024) |

15% (2020) |

81 / 142 (2024)

0.50 (2024) |

Accession 2009 |

20 (not free) (2024) |

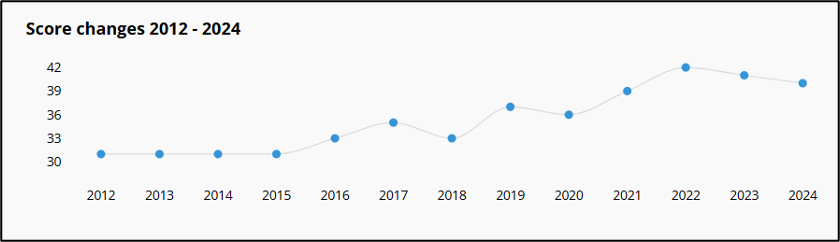

As seen in Table 1, Vietnam scores relatively low in indicators of corruption, suggesting that there are problems in the country regarding political corruption. However, there has been moderate improvement on the scores over recent years. For example, while Vietnam’s CPI score is still fairly low, there has been notable improvement since 2012, with its score going from 31 out of 100 in 2012 to 40 out of 100 in 2024:

Figure 1: Vietnam’s CPI score (out of 100) from 2012 to 2024

Source: Transparency International 2024.

Vietnam’s rule of law indicator from the Worldwide Governance Indicators has also strengthened in recent years, suggesting that the country has improved several factors such as control of organised crime, speediness of judicial processes, confidence in the police force, and other security matters (World Bank n.d.). However, Freedom House (2024) assesses that Vietnam is “not free”, noting that opposition to the CPV is banned in practice and that freedom of expression, religious freedom and civil society activism are tightly restricted.

Additionally, Vietnam currently sits on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) list of jurisdictions under increased monitoring (otherwise known as the “grey list”). The FATF notes that while Vietnam has taken steps towards improving its anti-money laundering (AML) regime and ensured the independence of its financial intelligence unit, there are still strategic deficiencies including its domestic coordination and cooperation in its AML, a need to improve targeted financial sanctions, customer due diligence and suspicious transaction reporting, beneficial ownership reporting, among several others (FATF 2025).

Forms of corruption in Vietnam

Bribery

The literature indicates that bribery is pervasive in Vietnam and regularly occurs at lower levels of the public sector – including at traffic stops, permit applications or other public services – to higher levels, with complex corruption schemes involving government officials and large sums of money (Tran 2023). Since January 2021, largely due to the “burning furnace” campaign, 1,400 party organisations were disciplined for corruption, a large number of these including bribery cases (Abuza 2024). However, while these numbers may indicate a commitment to punishing corruption, some argue that the CPV only prosecuted lower-level party officials and regulators, while the higher-level party officials have enjoyed impunity (VOA News 2024).

There have been widespread cases of public and political officials accepting bribes in various sectors, such as food safety department officials accepting bribes for fast-tracking approvals to 25 people including high-ranking officials and a former minister, who were imprisoned for extorting money from people taking repatriation flights during the Covid-19 pandemic (Vinex Official 2025; Thuy et al. 2023; Nguyen at al. 2023; Shad 2023).

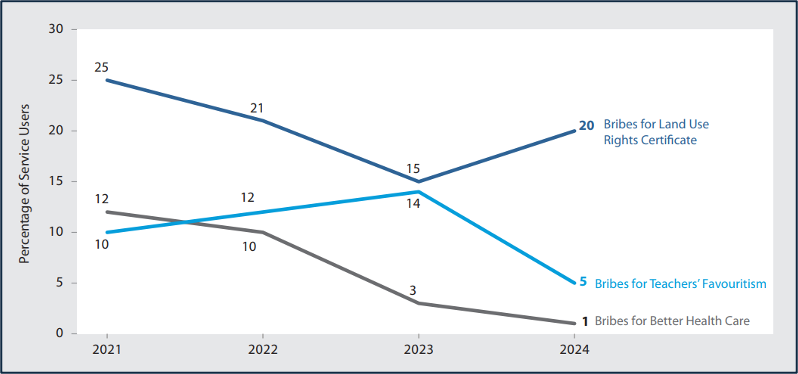

Figure 2 below estimates the petty bribe frequency reported by public service users (collected by the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index) in Vietnam in three different areas:

Figure 2: Estimated bribe frequency for public services as experienced by users, 2021-2024

Source: CECODES, RTA and UNDP 2025:18.

This data indicates that while bribes to teachers and healthcare providers have declined over the last three years, those for land use rights certificates are rising, and remain a considerable problem facing Vietnamese citizens. While the “burning furnace” campaign may have resulted in the prosecution of numerous corruption cases, the campaign has arguably failed to prevent everyday, petty corruption (Al Jazeera 2021). Citizens report that public officials such as law enforcement regularly demand bribes, known colloquially as nuôi công an or “feeding the police” (Al Jazeera 2021).

Larger scale bribery is reportedly commonplace when private businesses interact with public officials. This year, 30 former officials of northern Vinh Phuc, Phu Tho and central Quang Ngai provinces entered into court proceedings after having been accused of corruption, where prosecutors claimed that between 2010 and 2024, businesspeople had spent over US$5 million bribing public officials to win contracts in multi-billion-dollar infrastructure projects in the three provinces (France24 2025). Bribery is also considered a common strategy for local businesses when starting operations (VOA News 2024; Hung and Dung 2022:72).

Vu et al. (2023) used longitudinal data collected from surveys of small and medium sized companies in Vietnam and found that larger and more established businesses are more likely to pay bribes, which are often greasing and rent-seeking bribes, than smaller informal businesses in provinces with poorer business environments. Their evidence also suggests that international companies working in Vietnam tend to transfer the risk of bribery through subcontracting bribery-related transactions to third parties or intermediaries, rather than handling it themselves (Vuong, Bach and Vu 2024). Other research finds that bribery regulations and punishments result in lower levels of bribery in small and medium businesses in Vietnam, but larger companies that can afford higher bribes will continue to do so (Hung and Dung 2022).

The negative impact of bribery is notable on the economy, particularly in private sector investment. Research finds that excessive bribes have reduced the amount of investment by Vietnamese companies, particularly when the unofficial expenses exceed 10% of revenue of the businesses as this is when they become too much of a burden, and companies then avoid making longer term investments (Phuongo 2020).

Additionally, a study into a dataset from the survey of small and medium scale Vietnamese manufacturing companies by Efobi, Vo and Orkoh (2021) finds that, when a business pays a bribe, it reduces the wages of its employees (predominately those with the highest wage bracket) by an average of 27.6%. They find that businesses transfer the cost of bribery to their employees, while the businesses ultimately benefit from paying the bribe.

Bribery in infrastructure and other large-scale projects in Vietnam has also undermined investor confidence and may be deterring potential funding from international sources. For instance, in 2020 the World Bank Group announced the six-year debarment of an individual who had solicited bribes and failed to disclose his relationship with a bidder in the Da Nang Sustainable City Development Project, which included initiatives such as promoting more environmentally sustainable transport modes for Hanoi (World Bank Group 2020).

Several studies suggest that the cause of high levels of bribery in Vietnam is low public sector salaries (Pham 2024; Duong 2015). Nguyen and Nguyen (2023:17) note that public sector salaries are neither competitive nor performance based, that there are many regulations on additional subsidies and incomes, and that there is a lack of job description and result-based promotion mechanisms, all of which has led to public sector workers to seek bribes to supplement their incomes. Even some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) report paying bribes to public officials facilitate their work (Behrens 2024:182). This is reportedly further exacerbated by high levels of bureaucracy that increases the processing time for receiving permission for events (Behrens 2024:182). While the government has attempted to address this issue by increasing public sector salaries in recent years (VOA News 2024), many still argue that the salaries remain inadequate for the cost of living in Vietnam.

Embezzlement

Bribery and embezzlement are often intertwined in Vietnam. For instance, there have been documented cases of employees at the State Bank of Vietnam receiving bribes to change their inspection results and cover the bank’s wrongdoings, through allowing the embezzlement of funds (RFA Vietnamese 2023). Despite recent economic liberalisation in the country, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) continue to dominate the landscape and create these opportunities for corrupt officials (EFA 2019).

One recent highly publicised case of embezzlement was the case of Truong My Lan, which led to the controversial use of the death penalty (later changed to life imprisonment) (Du and Ha 2024; Reuters 2025). Lan owned 91.5% of Saigon Commercial Bank and over 10 years ordered bank officials to approve more than 2,500 loans to shell companies that she owned, causing the bank to lose approximately $27 billion (RFA Vietnamese 2024). This amounted to approximately the equivalent of 3% of Vietnam’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Hutt 2024). European Union (EU) partners were particularly critical of the use of the death sentence for corruption (Hutt 2024). Furthermore, others have criticised the court’s ruling on this case, noting that it only focused on punishing Lan and Saigon Commercial Bank and recovering assets, while it failed to compensate the bank’s customers who were the direct victims of the fraud (RFA Vietnamese 2024).

In a similar case, a Hanoi court sentenced the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology’s former chief accountant to death after being convicted of embezzling more than US$6.2 million between March 2009 and February 2023, modifying financial statements to do so (Nguyen 2024). Two other institute directors and another former chief accountant were also sentenced to prison for failing to act responsibly in this case (Nguyen 2024).

Embezzlement has an especially negative impact on the allocation of public funds for public services. Research into panel data in 63 provinces and cities in Vietnam found that corruption (particularly embezzlement) weakens the positive impact of local spending on educational achievements and, when combined with nepotistic hiring practices, results in a decrease in the local labour quality, having an overall detrimental effect on human capital in Vietnam (Hoa 2018).

Nepotism and favouritism

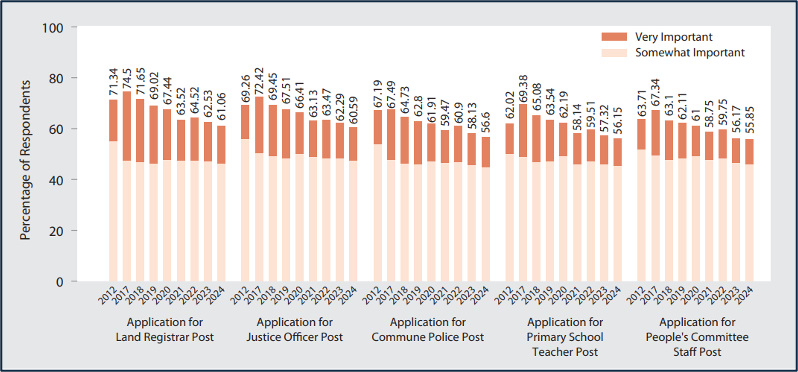

Nepotism is widespread within the political elite circles in Vietnam, particularly in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the ruling party (Fforde 2024; Duong 2015). Between 56% and 61% of Vietnamese citizens surveyed in the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index consider that personal connections are required for applying for civil service positions, highlighting particular concerns around the prevalence of nepotism in recruitment practices in the public sector:

Figure 3: Trends in citizen perception of the importance of personal connections for selected civil service positions, 2012-2024

Nepotistic practices have led to civil servants being employed based on personal connections rather than meritocracy (Duong 2015:26). It reportedly affects every aspect of the public sector, from healthcare, land management and construction to education, directly affecting the capability of these public mechanisms (Duong 2015:26). Senior party leaders have the final say on nepotism and favouritism in the bureaucracy and have also had control over the privatisation of SOEs and the emerging private sector, leading to further opportunities for corruption and crony collusion (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023:2).

One of the key challenges is the influence of entrenched interests, where individuals who have benefited from the current system have resisted reforms that threaten their power (Fforde 2024: Cuong 2024). The long-standing one-party system is reportedly central to this, which primarily enforces top-down policies that maintain the status quo (Cuong 2024:20).

Ishizuka (2020) lists a number of major nepotism cases at the central, provincial, district and commune level in Vietnam in recent years. To note a few, in 2017 the former minister of industry and trade was dismissed from state positions for scandals that included the appointments of his son to leadership positions in SOEs; another case included four siblings and one nephew who worked as leaders in the district people’s committee offices and the district party committee in An Duong district, leading to the secretary being reprimanded and family members transferred elsewhere in 2018; and in 2016, the party secretary, People’s Committee chairman, and deputy chairman in the Ha Son Commune Party were found to be relatives, and nine other officials were also found to be related to them (Ishizuka 2020:289-290).

Nepotism in the public sector has been found to lead to distorted public spending across the country. One study from 2011 investigated a dataset on promotions of public officials in Vietnam to understand their impact on the public infrastructure of their hometowns. Nguyen, Do and Tran (2011) found that there was a strong positive effect on several outcomes, including roads to villages, marketplaces, clean water access, preschools and irrigation, as well as the hometown’s propensity to benefit from the state’s “poor commune support programme”. They note that this nepotism is not only limited to top-level officials but is also pervasive to those without direct influence over shaping budgetary policies, indicating that nepotism in Vietnam works through informal channels.

Finally, at the municipal level, Mahanty and Dang (2015) found that horizontal ties among commune authorities (society) were stronger than vertical connections to higher levels of government (the state). This suggests that individuals often feel a greater personal obligation to their communities than to the formal state apparatus, a dynamic that can foster nepotism and favouritism at the local level.

Corruption risks in the implementation of Vietnam’s (NDCs)

Vietnam is particularly vulnerable to climate change threats, with its average temperature having risen 0.5°C–0.7°C in the past 50 years, and 70% of its population being vulnerable to hazards such as tropical monsoons (Huynh 2016:3). In response to the growing risks of climate change both in Vietnam and globally, the country joined the international community in becoming a party to the Paris Agreement and subsequently submitted its first nationally determined contributions (NDC) in 2016, with updated NDCs published in 2022 (NDC Partnership n.d.).

To meet its NDC target, Vietnam is aiming for a 15.8% reduction in its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions below business-as-usual levels (BAU) by 2030, and up to 43.5% reduction below BAU with international support (UNDP n.d.). In 2021, Vietnam also announced its intention to reach net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, alongside commitments to phase out coal and curb methane emissions (CAT 2023).

The key government ministries responsible for overseeing the implementation of its NDCs are the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, the National Committee on Climate Change and the Ministry of Planning and Investment, with financial support provided by a number of countries and international financial institutions, such as Denmark, Germany, Japan, the Asian Development Bank and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (NDC Partnership n.d.).

The climate change mitigation sectors included in Vietnam’s NDCs are energy, agriculture, land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF), waste and industrial processes (UNDP n.d.; NDC Partnership n.d.). As such, there is a broad array of sectors that will be affected. The following section provides an overview of corruption risks noted by the literature in two sectors key to Vietnam’s NDCs that are particularly prone to corruption risks: the energy and forestry sectors. While these include emerging areas, some literature is already pointing to risks that have been observed or considered to be likely issues in the future.

The energy sector

In 2022 at the COP27, the International Partners Group (IPG) and Vietnam announced a Just Energy Transition Partnership204598e1f6aa (JETP), meaning that by 2030 funding worth US$15 billion will be mobilised to help the country achieve its net-zero commitment by 2050 (Wischermann 2023; Gverdtsiteli 2024:16). Vietnam’s policy and investment plan under the JETP is to phase out coal and expand the use of renewables (BMZ n.d.). JETP is one of the primary schemes used for Vietnam’s green energy transition, among others, which include green bonds, blended finance and domestic and private sector investment.

To achieve an equitable and socially inclusive green energy transition, Vietnam needs to implement significant policy, legal and financial reforms to change its energy system and reduce the emission of GHGs. Vietnam is still heavily dependent on coal and is one of the fastest growing per capita GHG emitters worldwide, despite being one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change (International Rivers and the Vietnam Climate Defenders Coalition 2024:4). In recent decades, much of Vietnam’s economic growth can be attributed to the exploitation of its natural resources, which has significantly included the exploitation of fossil fuels (World Bank 2011a).

Broadly speaking, Vietnam’s energy sector is considered to be one of the country’s corruption vulnerabilities, as investors in energy have reportedly been frustrated by opaque regulations, red tape and the slow pace of policy implementation (Abuza 2024). Climate change plans (which include the green energy transition) are centralised and top-down in Vietnam and are often detached from local realities, which leads to slow or incomplete implementation (Strauch, du Point and Balanowski 2018:39). Research indicates that the most common weakness at the provincial level of climate change planning is that the local climate action plans are poorly integrated into local planning and budget processes, with some reporting that the current approach to climate change planning is that it is a “money-making machine for consultants with little effect on changing investment choices” (Strauch, du Point and Balanowski 2018:46).

There are numerous reports of corruption scandals affecting the energy industry. For example, in December 2023, the former chairman of the Vietnam Oil and Gas Group was arrested for taking bribes from Xuyen Viet Oil and Gas Co (Abuza 2024). The firm’s mismanagement played a large part in the oil shortages in Ho Chi Minh City in the third quarter of 2022 when there was a 40% decline in oil imports and a 35% decline in diesel imports (Abuza 2024). In January 2024, at the 25th Central Inspection Commission1dc92bf3cead session, over 80% of those disciplined were from SOEs or government entities that were involved in the energy sector (Abuza 2024). Finally, senior trade officials have been accused of mishandling the nation’s nearly US$300 million petroleum price stabilisation fund (Bloomberg News 2024).

These risks continue to cast a shadow over Vietnam’s progress in implementing the green energy transition under the JETP, with analyses indicating that the oversight mechanisms governing this transition have been insufficiently robust. For example, Gverdtsiteli (2024) examines governance processes in three JETP countries – South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam – and notes that poor governance and a lack of transparency is prevalent throughout each of these. Notably, when Vietnam’s JETP governance plan was being developed, anti-corruption civil society organisations and experts were not involved in the planning process and anti-corruption measures were not adequately assessed, with anti-corruption only mentioned briefly with no thorough risk assessment conducted (Gverdtsiteli 2024:5, 17).

Similarly, Wischermann (2024) highlights this lack of accountability and oversight mechanisms. While the JETP declaration in Vietnam emphasises the rights of workers affected by the energy transition, it does not explicitly mention civil society (Wischermann 2023). During the 2021 JETP negotiations, four of the most prominent representatives from Vietnamese civil society were arrested under the pretext of tax evasion and sentenced to prison (Wischermann 2023). This, among other incidents in Vietnam, has led to academics and activists criticising the IPG leaders for a lack of action regarding human rights violations (Gverdtsiteli 2024:22).

Gverdtsiteli (2023) also finds that, despite the Vietnamese government opening up to international donors through funding its environmental projects and facilitating knowledge exchange, there is still little scope to influence policymaking processes and policy implementation in the country beyond these project opportunities. The CPV continues to keep foreign development actors out of these decision-making processes in regard to environmental decisions, suggesting that the party continues to defend its political interests on the domestic front (Gverdtsiteli 2024).

Abuse of power and undue influence of commercial interests in the JETP is another risk as, while the Vietnamese resource mobilisation plan (RMP) acknowledges a “just transition” as one that brings social benefits to wider society, it lacks a dedicated working group to assess people’s needs and the impacts of the transition on the population (Gverdtsiteli 2023:29). One illustrative case of this was in 2024, when a former deputy minister of industry and trade was jailed for six years after being found guilty of abuse of power in a solar energy development plan (France24 2025). The individual had admitted to taking a US$57,600 bribe to favour solar power plants in the Ninh Thuan province over others (France24 2025). The Vietnamese government also launched a probe into 32 wind and solar projects over allegations of abuse of power in 2024 (Sanderson 2024).

The forestry sector

The forestry sector is another significant focus area for Vietnam to achieve its NDCs, particularly as its forests act as carbon sinks, meaning they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. More than 40% of Vietnam is covered by some form of forest, making Vietnam a key target for donor REDD+ investments (Huynh 2016). In 2017, Decision No. 419/QD-TTg was issued, which meant that the Vietnamese government had approved the national programme on the reduction of GHGs through the reduction of deforestation and forest degradation, sustainable management of forest resources, and conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks (REDD+) by 2030 (Thuy et al. 2019:15).

During COP26, Vietnam also made a commitment to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 with its participation in the voluntary carbon market as a one of the key strategies of achieving this (WTO Center 2023). A pilot emissions trading scheme (ETS) project was launched in June 2025 and will ultimately be eligible through both domestic and international mechanisms, including the clean development mechanism (CDM) and the joint crediting mechanism (JMC) (ICAP 2025; Bo-Yu 2025). These projects are broadly under the mandate of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and are expected to substantially expand in the coming years, with subnational governments acting as the implementing bodies (Pham et al. 2021:4).

Given that the carbon market is an emerging sector in Vietnam, there has been little published to date on evidence of forms of corruption and corruption risks in the associated projects. Some corruption risks have been reported or may occur during the counting of carbon emission reductions, bribery during project approval, and regarding uncertain land tenure for local communities and unequal benefits distribution.

Firstly, concerns have been raised recently regarding Vietnam’s official trading platform for the country’s carbon credits, as this has yet to be announced (Bo-Yu 2025). Additionally, the emissions allowance allocation process will be coordinated across multiple ministries, which differs from the single-agency approach used in most countries and may cause oversight issues in the future (Bo-Yu 2025). While this does not constitute evidence of corruption, these vulnerabilities could create conditions conducive to future corruption risks if oversight mechanisms are not rigorously maintained.

In global carbon markets more broadly, several corruption risks have been noted in the literature. For example, recording transitions and ownership of carbon credits has historically been an issue as voluntary carbon credits do not have the same security used for financial or energy markets, making these credits a potential vehicle for money laundering and bribery (Marks and Scotland 2025:11). There is also a lack of benchmarked prices and standardised contracts, making monitoring suspicious transactions more challenging than in more established markets (Marks and Scotland 2025:11).

At the project development stage of reforestation and forest preservation, Marks and Scotland (2025:7) note that, in jurisdictions with political instability and weak governance, risks may arise such as contested land tenure, violations of community rights, forced resettlement, bribery during permitting processes and inadequate environmental management. Some of these risks have been observed in the forestry sector in Vietnam, with corruption scandals that have involved responsible government agencies, such as the 2023 dismissal of the director general of the department of national parks, wildlife, and plant conservation for receiving bribes (B.Tribune 2023; Abuza 2024).

Huynh (2016:10) notes that corruption is prevalent in the forestry sector in Vietnam largely due to several factors:

- inconsistences in legislation and policies that create gaps in which bribery can thrive

- the slow operation of the “one-stop-shop” office for forest licensing

- unclear division of duties and allocation of tasks among state officials at different levels

Corruption has reportedly played a role in determining who benefits from forests and how forest-related revenues from REDD+ projects are distributed. A participatory governance assessment for REDD+ projects was carried out, and it highlighted the importance of forest governance challenges, observing that the main corruption risks involved benefit distribution and forest law enforcement around forest land and forest contract issues (Hunyh 2016:13).

Research also indicates that these unclear land tenure regimes in Vietnam could increase the risk of powerful parties securing more rights, elite capture, and forest stewards being unable to participate in REDD+ projects and receive related revenues (Pham et al. 2021:10). The need to examine legal frameworks around land tenure at both national and subnational levels to identify areas of potential conflict with customary laws has been highlighted in Vietnam since 2012 (Hunyh 2016:20). Thuy et al. (2019:46) also echo concerns that securing land tenure can protect the rights of local communities and ethnic minorities, but that this remains a significant issue in Vietnam.

Further complicating the matter, the two responsible ministries for the carbon market, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, reportedly hold different beliefs around who forest carbon rights belong to, which could pose additional problems for how revenues are distributed (Pham et al. 2021:10).

Finally, these risks may be potentially further complicated by wider political developments in the country, given that one of the reported unintended consequences of the crackdown on corruption are delays to infrastructure projects as public officials have been in “self-preservation mode” to avoid potential corruption allegations (Tatarski 2022). This has affected the land sector as officials are reportedly delaying important decisions in order to not make mistakes, particularly related to land valuation and compensation (Tatarski 2022).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework

Legal framework

International conventions and initiatives

Vietnam signed the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in December 2003 and ratified it in 2009 (UNODC 2009). It was reviewed by the UNCAC implementation review mechanism in 2011 and was found to have met almost all of the UNCAC requirements, particularly regarding an improvement in its legal systema551b2fd53f8 (UNODC 2023:4). However, the review found that there were deficiencies regarding the coordination between agencies responsible for anti-corruption, the expansion of signing bilateral mutual assistance agreements, expanding corruption crime regulations to the private sector, enhancing the independence of anti-corruption agencies, among several others (UNODC 2023:5).

In 2007, Vietnam’s anti-corruption agencies joined the South East Asia Parties Against Corruption (SEA-PAC) which is a channel of cooperation between anti-corruption agencies in the region to prevent and counter corruption (ASEAN-PAC n.d.:4).

Notably, Vietnam is not a signatory to the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention (1997).

Domestic legal framework

The Law on Anti-Corruption, passed in 2005, is one of the leading legal instruments used to counter corruption in Vietnam (Tran and Nguyen 2020). In 2012, amendments were made to the Anti-Corruption Law, including Decree 59 on the implementation of transparency chapters, Decree 78 on rules for asset and income declarations of public officials, and Decree 90 on the rights of businesses and citizens to enquire for information (Huynh 2016:5). It was further amended in 2018, and provides for the prevention and detection of corruption, including embezzlement, taking bribes, abusing one’s position or power for the illegal appropriation of assets, abuse of official capacity, among others.

The Vietnam penal code (updated in 2025) also criminalises corruption offences such as bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power. Originally, the penal code included the death penalty for bribery and embezzlement, but the 2025 update abolished this (Baker McKenzie 2025). The update also covers bribery of foreign public officials.

Additionally, the government adopted a national strategy on anti-corruption in 2020, which includes measures to raise awareness of anti-corruption laws and policies, as well as mobilise the active participation of its citizens in anti-corruption (Huynh 2016:4).

Contributions to political parties are not regulated in Vietnamese law, particularly as there is just one political party (Global Compliance News n.d.). However, public officials must report to their immediate supervisor all gifts given within five working days from the date of receipt (Global Compliance News n.d.).

Whistleblowing is covered by the Law on Denunciation No. 03/2011/QH13 which protects whistleblowers and their relatives, despite the individual having to give their name and address while making the report. Duong (2015:24) notes that the organised protection and confidentiality of whistleblowers is limited, with there being some cases of whistleblowers being prosecuted for exposing political elites.

The literature generally observes that the CPV has put in increasing efforts to curb corruption in recent years, with countering corruption high on the agenda. Several anti-corruption institutions and legal frameworks have been set up and strengthened as a result of this increased commitment (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023). Cuong (2024) positively notes that preventive measures have been the focus of Vietnam’s anti-corruption strategy and have included mandatory asset declarations for public officials, rules to prevent conflicts of interest and more transparency in public procurement processes.

However, research finds that there is still a large implementation gap and a lack of effective enforcement mechanisms (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023:3). There is arguably still the ineffective implementation of many anti-corruption laws and policies, particularly regarding measures on asset declaration and conflicts of interest, and a lack of preventive measures for collusion between high-ranking officials and private companies to manipulate public policies (state capture) (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023:18).

Other research into Vietnam’s public sector finds that anti-corruption policies are still inadequate and contribute to the normalising and acceptance of corruption in the public sector (Nguyen et al. 2023:63) This suggests that Vietnam still needs to develop a more robust and holistic anti-corruption framework and that the government and CSOs should work together to raise awareness of the impact of corruption to promote a culture of transparency, accountability and integrity (Nguyen et al. 2023).

Institutional framework

There are several government agencies from the national to local level responsible for overseeing anti-corruption efforts. The CPV steers the anti-corruption work through the Central Steering Committee for Anti-Corruption (CSCA), which is an advisory agency of the VCP (UNODC n.d.). The CSCA directs, coordinates and monitors anti-corruption efforts nationwide, particularly in more severe and complex cases (UNODC n.d.). The Central Inspection Commission of the Communist Party of Vietnam is responsible for countering and disciplining corruption and misconduct within the CPV (Vietnam News 2024).

The government inspectorate (GI) is a ministry-level anti-corruption agency responsible for inspection affairs on the works of government agencies and provincial authorities in line with the direction of the CSCA (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023). The state audit sits under the national assembly’s jurisdiction and audits, examines, and makes assessments and recommendations to the national assembly on public assets and finance, with the state auditor general elected by the national assembly (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023).

Provincial steering committees on anti-corruption also exist, under direct supervision of the CSCA, which develop and coordinate anti-corruption policies at the provincial level and monitor and supervise the anti-corruption action plan at the provincial and city level. They also investigate, trial and sentence corruption cases in their provinces and cities (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023).

Reportedly, these anti-corruption institutions are strong and well-coordinated at the central level, with 18 agencies in total involved but with strong coordination of the Central Steering Committee on Anti-Corruption and Wrongdoings (CSCACW) under direct leadership of the CPV’s General Secretary to address cross-agency cooperation and bureaucracy challenges (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023:12).

However, the close relationship between anti-corruption institutions and the CPV may create the false perception that anti-corruption is the CPV’s internal affair. Additionally, having multiple anti-corruption agencies has presented issues as their duties and responsibilities often overlap (Duong 2015:24). While the National Anti-Corruption Steering Committee (NASC) was established in 2006 to coordinate and organise these agencies, this has resulted in competition at the institutional level between agencies as their roles are still not fully clear (Duong 2015:24).

Due to nepotism and favouritism, local level anti-corruption institutions have been less successful than those at the central level (Nguyen and Nguyen 2023:13). Indeed, in July 2025, the party general secretary highlighted several of these issues, urging improvements in the operation of provincial steering committees and local anti-corruption bodies (Vietnam News 2025).

Other stakeholders

Media

The media in Vietnam is reportedly closely controlled by the CPV, with independent reporters and bloggers often imprisoned (RSF n.d.). The army has developed Force 47, which is a unit with 10,000 cyber-soldiers who are tasked with defending the party line and attacking online dissidents (RSF n.d.). The 2019 Cybersecurity Law requires online platforms to store user data on Vietnamese soil and hand it over to authorities when requested (RSF n.d.).

There have been some indications that public engagement has been successful in bringing corruption cases to light in recent years, such as the case of one individual who admitted in 2019 to bribing officials with millions of dollars to secure a deal when the company AVG was acquired by the state-owned telecom company Mobifone (Cuong 2024:18). Investigative journalists were central to uncovering this scandal through reporting on the irregularities and potential losses to the state budget, which led to public outrage (Cuong 2024:18).

However, this case may not be indicative of a general trend. In another instance, journalists from two newspapers in Vietnam, Thanh Nien and the Tuoi Tre, uncovered corruption in high ranks and broke the stories to the public, only to be later prosecuted for distributing false information (Duong 2015:24).

Civil society

There are few, if any, anti-corruption civil society organisations operating in Vietnam. Civic space is shrinking in the country, and human rights and environmental activists are facing growing repression from the government, including arrest (BMZ n.d.; Wischermann 2023). Freedom House (2025) categorises Vietnam as “not free” and reports that freedom of expression, religious freedom and civil society activism are tightly restricted, and that the government has cracked down on the use of social media and the internet to voice dissent. Nonetheless, international donors such as the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), the Danish International Development Assistance (Danida), UK Aid, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) have supported anti-corruption efforts in the country. For example, one project spanning between 2002 and 2009, which was funded by these donors, included several anti-corruption initiatives in Vietnam, such as transparency in public service delivery, legal sector reform, public financial management reform, among others (Norad 2011).

- JETPs are multilateral platforms between developed and emerging economies designed to deliver climate finance to support countries to transition to an equitable and socially inclusive low-carbon economy (Shai 2024). The International Partners Group (IGP) includes France, Germany, United Kingdom, United States and the European Union.

- The Central Inspection Commission is responsible for disciplining corruption and misconduct within the CPV.

- These included the issuance and amendment of important anti-corruption legal documents such as penal code 2015, criminal procedure code 2015, anti-money laundering law 2012, anti-corruption law 2012, law on denunciation 2012 and the circular on praising whistleblowers in anti-corruption cases (UNODC 2022:4).