Query

Please provide information and data on the relationship between corruption and human rights in Ecuador, as well as the existing links between gender and corruption in the country.

Caveat

There are very few publicly available resources on the topic of gender and corruption in Ecuador, which speaks to a need for more data and information on gendered forms and impact of corruption in the country.

Background and extent of corruption in Ecuador

Background

Ecuador is a South American country that gained its independence from Spain in 1830. It has adopted about 20 constitutions since independence, with its latest iteration in place since 2008 (Knapp et al. 2020). In the past three decades, the country has experienced periods of political instability, as evidenced by the election of six presidents between 1996 and 2006 who all failed to complete a four-year term (BBC 2018).

Between 2007 and 2017, the country was under the leadership of Rafael Correa, during which time the country experienced a decline in adherence to the rule of law, civic space and political opposition (Human Rights Watch 2017). Correa’s term in office came to an end in 2017 and his deputy, Lenin Moreno, was elected as president after winning the election as the candidate of the ruling party Alianza Pais (BBC 2018).

Upon assuming power, President Moreno promised to change governance style from that of his predecessor (Valencia 2017) and to curb corruption (Collyns 2017). A few months into Moreno’s term in office, Ecuadorians voted to reinstate the presidential limit to two terms, which had been removed from the constitution by the Correa in 2015, thereby restricting him from running for office again (The Guardian 2018). The new president also suspended his vice president, Jorge Glas, who was implicated in the Odebrecht scandal for accepting bribes worth US$13.5 million (Picard 2017). In 2018, another vice president, Maria Alejandra Vicuna, was suspended amid allegations that she took kickbacks during her time in congress (AP News 2018).

Another significant highlight was the conviction of former president Correa in April 2020 for accepting US$7.5 million in bribes during his time in office. He was sentenced in absentia to eight years in prison (Valencia 2020). An appeal court upheld the eight-year sentence, which effectively banned him from running for public office for 25 years (Moskowitz 2020).

Table 1: Ecuador’s performance on relevant governance indices

|

Government indices |

Score |

|

CPI score and rank 2019 |

38 (93 out of 180 countries) |

|

Freedom House |

65 (partly free) |

|

2020 CIVICUS Monitor |

Obstructed |

|

2019 EIU Democracy Index |

6.33 (flawed democracy) |

|

2019 WGI: Control of Corruption |

-0.50 |

|

Rule of Law Index 2020 |

0.49 |

|

Press Freedom Index 2020 |

32.64 |

|

IPI 2019 |

5.95 |

|

2019 Global State of Democracy: Checks on Government |

0.54 |

Extent of corruption

Corruption remains a major challenge in the country. According to Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Ecuador scored 38 out of 100, where 0 indicates the most corrupt and 100 the most clean. This places the country in 93rd place out of 180 countries (Transparency International 2019a). The country’s CPI score has increased steadily from 31 in 2016, but the current score of 38 is below the regional average of 43 and still ranks lower than the majority of countries in the region.

Ecuador also underperforms on various components of the Worldwide Governance Indicators, which rate performance from -2.5 (worst) to +2.5 (best). For instance, it scored -0.50 on control of corruption, -0.58 on rule of law, -0.40 on government effectiveness, and 0.06 on voice and accountability (World Bank 2019). These poor performances form the backdrop to the public’s loss of confidence in the government, with the latest Latinobarometer showing that Ecuadorians’ government approval dropped from 66% in 2017 to 46% in 2018, and only 25% of citizens have trust in the government (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 45, 54).

The majority of Ecuadorian respondents (56%) in the latest edition of the Latinobarometer perceived that the levels of corruption had increased in 2018, which though troubling is somewhat below the regional average of 65% (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 62). Despite the perceived increase in corruption, surprisingly only 8% of respondents regarded corruption as the main problem in Ecuador,9af88092b41c compared to 20% of people in Colombia and 19% in Peru (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 59). This could be related to the change in government at the time the data was collected, with the new president Moreno promising to curb corruption and stripping former vice president Jorge Glas of his powers when he was convicted of accepting bribes in the Odebrecht scandal (Picard 2017; BTI 2020; Freedom House 2020).

When asked about the most corrupt institutions in Ecuador, respondents ranked judges and magistrates (59%) as the most corrupt, followed by councillors (59%), parliamentarians (58%), businesspeople (56%), officials of the national tax office (55%), the police (54%) and public officials (54%) (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 67).

However, since the political transition in 2017, there have been some improvements in democracy and the rule of law. For instance, Ecuador has advanced on the Democracy Index over the past five years from a hybrid regime to a flawed democracy, and currently has a score of 6 out of 10, with 0 indicating total authoritarian regime and 10 indicating full democracy (Economic Intelligence Unit 2020). Intriguingly, the 2018 Latinobarometer showed that support for democracy was at its highest (71%) in 2015 during Correa’s presidency, but had gone down to 50% in 2018 (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 16).

The Bertelsmann Foundation suggests this could be partly attributed to the populism of the previous administration as the former president Correa enjoyed more citizen support than his successor and “portrayed his administration as one turning the country into a real democracy” (BTI 2020). However, the report also cautioned that evaluation of “citizens’ approval of democratic norms and procedures” is complex in Ecuador as data does not always indicate clear trends. For instance, when asked whether they preferred to have a democratic or a non-democratic regime, 26% of Ecuadorian respondents said it did not matter, showing that a large percentage of the population has no commitment to basic conventions and values of democracy (BTI 2020).

On a positive note, many Ecuadorians believe they can play a part in curbing corruption. When asked whether it is better to keep quiet if they know of something corrupt, marginally more people disagreed than agreed (49% to 47% respectively) (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 63). However, Ecuadorians have the highest tolerance for corruption in the region, with only 58% of citizens agreeing that they become an accomplice if they do not report an act of corruption they are aware of, compared to countries such as Brazil (82%) and Argentina (80%) (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018: 64).

Gender and corruption

There is very little information on the relationship between gender and corruption in Ecuador, despite the increased focus on the topic in Latin America in recent years (Ferreira et al. 2016; López 2019). For instance, the 2019 Global Corruption Barometer for Latin America and the Caribbean highlighted that one in five people had experienced or knew someone who had experienced sextortion when accessing public services, with a majority of the victims being women, who are usually primary caregivers for their families.

In addition, 71% of respondents believed that sextortion happens at least occasionally in the region (Transparency International 2019b: 20-21). Though the report did not include data from Ecuador, it gave a clear picture of the problem of gender and corruption across the region.

The only available study on Ecuador was carried out in 2017 by the Center for the Study of Situations of Bribery, Extortion and Coercion, which surveyed 308 rural-based women regarding their experience of corruption in their daily lives. According to the results, 57% of the respondents said they had experienced extortion from public officials and teachers (Santos 2018). This corresponds to findings from the 2019 Global Corruption Barometer, which showed that women in Latin America are more likely to pay bribes for health services and public school education compared to other sectors, whereas men are more likely to pay bribes for police, utility services and identity documents (Transparency International 2020b: 20).

About 35% of the 308 respondents said they had resisted extortion, but only a small number of those who refused to comply with a demand for a bribe were still able to access the public service they were seeking (Santos 2018). The study illustrates how corruption affects a majority of rural women in Ecuador who are subject to extortion, with the result being that many of those who are unable or unwilling to pay are denied access to public services, which they heavily depend on as the primary caregivers of their families.

It is worth mentioning the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) indicators, which measured gender equality in Ecuador with a range from 0 (extremely unequal) to 4 (equal). Gender inequality in access to public services is categorised as extreme (-0.1), which means 75% or more of women lack access to basic public services of good quality based on their gender. Gender inequality in accessing state business opportunities is categorised as extreme (0.67), meaning 75% or more of women are restricted access to state business opportunities even when they are qualified. Access to state jobs is ranked as unequal (1.58), meaning at least 25% of women cannot access state jobs even if they are qualified, due to their gender. In the area of civil liberties, Ecuador scores 1.39, meaning women have substantially fewer civil liberties than men (V-Dem Institute 2019).

Such gender inequalities can lead to higher corruption risks for women. Systematic discrimination against women produces social dynamics that generate and facilitate gendered forms of corruption, such as sextortion, as women are forced to pay bribes to access equal opportunities and services. Various studies from Latin America and beyond have shown that women and girls encounter coercive sexual demands to obtain land, a business permit, a work permit, public housing or even good grades (Transparency International 2020b; Sierra and Boehm 2015; Transparency International 2015). In addition, gender inequalities make it harder for women as victims of corruption to seek justice for corrupt abuses of power as they fear possible reprisals, discriminatory myths and social stigma associated with sex and corruption (Castro 2018; Carnegie 2019).

Corruption and human rights

The impact of corruption on human rights varies from clear and specific violations of individual rights to the manner in which corruption functions as an obstacle to the wider realisation of human rights (Chêne 2016; U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, no date). Corruption can constitute a direct human rights violation when the intent of the act is specifically to restrict a human right; for example; through bribing or politically influencing judges to deny due process and a fair trial to a defendant, or vote buying to undermine the right to political participation. In some instances, the intention may not be to violate human rights, but the effect is the same. For example, when public officials demand payments for services that should be free they restrict the intended beneficiaries’ access to public goods to which they are entitled. Overall, corruption diminishes public trust and weakens the ability of the government to respect, protect and fulfil human rights (Chêne 2016; U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, no date).

The following are some examples of the relationship between corruption and human rights in Ecuador.

Economic, social and cultural rights

Right to health

Corruption in the health sector in Ecuador ranges from favouritism in the placement of health centres to embezzlement or mismanagement of health funds. For instance, it was recently reported that there was an unfair and preferential “distribution” of hospitals in Ecuador, which favoured provinces where certain National Assembly members came from, which prompted an investigation by the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control into possible corruption (El Universo 2020). There is as yet no information on whether the investigation has been completed, but such alleged clientelist distribution of medical centres leads to the marginalisation of citizens in non-favoured areas, whose right to access health services is restricted.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated corruption in Ecuador’s health sector as criminals aim to benefit from the increased demand for medical supplies (Posada 2020; Espinoza 2020). According to a recent report by the comptroller general, there is evidence of hospitals purchasing overpriced medical kits without following procurement rules (Contraloría General del Estado 2020). For instance, the report finds that hospitals in Guayaquil purchased body bags for US$615,000 when they should have cost US$46,910. The responsible officials did not justify why they did not seek alternative offers from state contractors or why an unregistered contractor was invited to participate directly in the procurement process (Kitroeff and Taj 2020; Hurtado 2020).

As the above corruption scandal unfolded, Ecuador’s health sector was under enormous strain and the country’s COVID-19 death toll was one of the worst in the world (Cabrera and Kurmanaev 2020). Ecuador’s attorney general accused unscrupulous individuals who profited from the suffering of many people of immorality against the backdrop of such human suffering (Kitroeff and Taj 2020). This one example illustrates how corruption in Ecuador’s COVID-19 response restricted the government’s ability to effectively fulfil the right to health for all citizens.

Right to an adequate standard of living

As noted by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (2019: 53), corruption affects the financial ability of Latin American states to fulfil their human rights obligations, particularly those rights related to providing an adequate standard of living, such as food, water and housing. It exacerbates poverty as much-needed resources to the standard of living are diverted into private pockets.

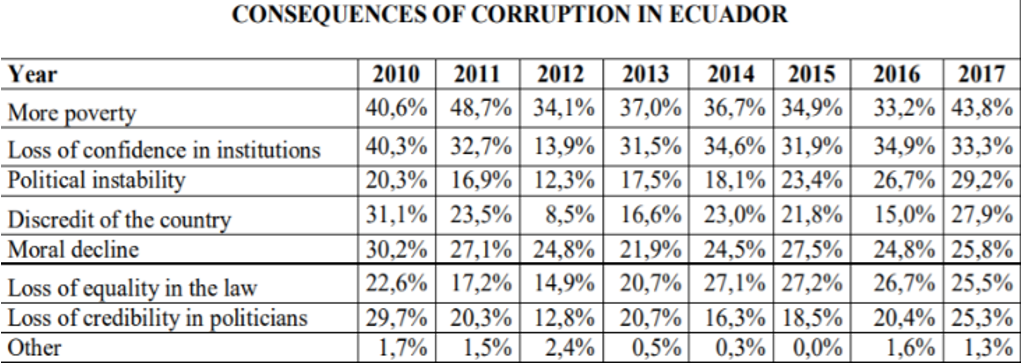

The diagram below shows perceptions of corruption by poor people in Ecuador from 2010 to 2017.

Consequences of corruption in Equador

Source: Tobar-Pesántez, L. and Solano-Gallegos, S. 2019, p. 5. The perception of poor people from the Canton of Cuenca-Ecuador on corruption (2010-2017).

As shown above, most respondents perceived poverty as the main consequence of corruption in the country. When asked who is most affected by corruption, the majority of respondents (average 49% from 2010 to 2017) agreed that corruption mainly affects the poorest people (Tobar-Pesántez and Solano-Gallegos 2019: 8). In the eyes of citizens, corruption in the country clearly affects the right to an adequate standard of living for the poor and disadvantaged.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened economic conditions and hunger, more people in Ecuador have turned to food relief programmes (Reyes 2020). However, these programmes are also prone to corruption. In May 2020, the then-director of the National Risk Management Service resigned following an investigation by the attorney general’s office regarding corruption in the procurement of 7,500 food kits to be distributed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Medina 2020). According to reports, baskets were fraudulently purchased for US$150 each, when the market value was less than US$85 (Primicias 2020). Had the government procured each basket at market value, it would have almost doubled the number of purchased baskets and ensured that more people had access to food. Hence, corruption restricted the ability of the government to fulfil the right to food for people who missed the few food kits bought for inflated prices.

Rights of indigenous communities

Ecuador is rich in natural resources such as gold, silver and crude petroleum. Though the extractive industry contributes to more than half of Ecuador's exports, it is also characterised by a lack of transparency in financial as well as environmental impact data (GAN Integrity 2020). This opacity has severe consequences: in 2019, President Moreno stated that a special audit into US$4.9 billion worth of oil-related infrastructure investment in the past 10 years had revealed that approximately US$2.5 billion was lost to corruption (Pipoli 2019).

Most mining deals are reportedly negotiated and approved through corrupt means, without due consideration to the impact on the environment or affected indigenous communities (Koenig 2019). According to reports, most controversial contracts in recent years have been signed with companies from China, which is Ecuador’s largest creditor, and most deals are tailored to line the pockets of oil executives, middlemen and government officials (Zuckerman 2016).

Though indigenous communities have a constitutionally guaranteed collective right to “free prior informed consultation” in projects that could affect them environmentally or culturally, Magdaleno (2018) states this right is frequently violated in practice as the private interests of oil companies and public officials are prioritised over the rights of indigenous communities. On the last visit to Ecuador in 2018, the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples pointed out that the government was failing to adequately consult or the obtain the consent of affected indigenous people in extractive projects (Tauli-Corpuz 2018).

On a positive and historic note, the Waorani indigenous community recently succeeded in preventing the government from selling their indigenous land to oil companies without due consideration to their right to be properly consulted (United Nations Development Programme 2020).

Civil and political rights

Right to a fair trial

Corruption in Ecuador’s justice sector ranges from bribery to political interference in judicial work (US Department of State 2019). According to the 2018 Latinobarometer, 59% of respondents from Ecuador believed that judges and magistrates were engaged in corrupt activities, higher than the percentage who held the same view of the police (54%) (Latinobarómetro Corporation 2018). Such high levels of corruption in the judicial sector damages the right to a fair trial as corruption erodes the independence, impartiality and integrity of the judiciary.

According to the US Department of State (2019), judicial corruption in Ecuador affects the right to a fair trial as judges and magistrates reportedly adjudicate cases excessively hastily or slowly depending on political influence. Before the transition in 2017, human rights activists and protestors were arrested, and the judiciary played a part in convicting them for dubious crimes such as “blocking public thoroughfares” or “rebellion” (Pásara 2014: 2-4). Human Rights Watch (2020) also confirms that corruption, inefficiency and political interference had infested Ecuador’s judiciary for years and it was common for the government to interfere in cases involving its interests. As the independence of judges is a prerequisite for fair and just trials, such political interference affects the right to a fair trial as predictability and transparency in judicial processes could be impeded.

Though the new government has improved judicial integrity and independence, the country’s Organic Code on Judicial Function still exposed judges to political pressure through a broad rule allowing the suspension or removal of judges for “criminal intent, evident negligence or inexcusable error” (Human Rights Watch 2020). Previously, the broad rule was abused to suspend or remove 145 judges between January 2013 and August 2017, as well as 19 judges between January and August 2019 for “inexcusable errors” in their judgments (Human Rights Watch 2020).

The Organic Code was reformed in December 2020, including new measures on the concept of inexcusable error (Samaniego 2020). According to reports, the Council of the Judiciary will only be able to exercise disciplinary actions against judicial officers for an inexcusable error if there is a prior ruling from a judge. This will likely limit political intimidation of judicial officers by the Council which previously had the sole discretion to discipline officers without any ruling from a judge (Lahora 2020).

Right to security of the person

The right to security of the person is under threat due to the increased rate of drug trafficking in Ecuador. According to Insight Crime, the country has silently become a key piece in the global drug trade, providing major drug trafficking routes to the US and Europe. Organised drug traffickers usually rely on networks of corrupt officials to ensure the smooth shipment of drugs, and have even reportedly provided security for drug shipments and their traffickers, as well as transported drugs in their official vehicles and carried out assassinations on behalf of the traffickers (Bargent 2019a).

As a result, there is a rise in violent crimes and murder rates in border provinces such as Esmeraldas and Sucumbíos where traffickers operate with impunity as corrupt security officials turn a blind eye (Bargent 2019b; Bargent 2019c). Hence, corruption and organised crime have restricted the right to security of the person due to increased violence and crime in border provinces.

Conclusion

Corruption has a negative impact on gender and human rights in Ecuador. It affects a majority of women who experience extortion when seeking public services, and those who are unwilling or unable to pay are more likely denied access to services. In addition, systematic discrimination against women in Ecuador, as shown by V-Dem indicators, can produce social dynamics that generate and facilitate gendered forms of corruption such as sextortion as women are compelled to pay bribes to access equal opportunities and services to men.

Corruption also affects social, economic and cultural rights such as the rights to health and an adequate standard of living, as it hinders the government’s financial ability to provide basic services to citizens. In addition, political interference in the judiciary compromises the right to a fair trial as it impedes predictability and transparency in judicial processes. Lastly, corruption in Ecuador’s security forces facilitates a growth of drug trafficking, which greatly affects the right to security of the person due to increased crime.

- The survey did not mention what was perceived as the most problematic issue in Ecuador.