Query

We would like an update of the overview on corruption and anti-corruption in Sudan. In particular, we would be interested in the role and results of the Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee and the overall role of state/military-owned companies in the transition process in Sudan.

Background

Following the ousting of President Omar al-Bashir and his National Congress Party (NCP) in 2019, Sudan’s transition to democratic rule has been denoted by a failing economy; political tensions; and continuing widespread protests for justice and reforms. These challenges are aggravated by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic (HRW 2021).

The military leaders and civilian protesters who overthrew the previous repressive regime are “uneasy partners” in a transitional government (Freedom House 2020a). Initially, the military forces had taken control of the country; however, citizens’ protests continued. In June 2019, security forces under the Transitional Military Council (TMC) killed 127 protesters in the capital Khartoum, resulting in a backlash that ensured that the short-lived junta include civilian leaders in a new transitional government headed by the Transitional Sovereign Council (TSC) in August 2019. The elections have been set for late 2023 or early 2024 after a 39-month transitional timeline was agreed upon (IFES 2021). After the Juba peace agreement of 2020, rebel groups were also included in the Sovereign Council and the Council of Ministers, which are vital parts of Sudan's executive body (Sudan Information Service 2021). Despite the challenges, the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) (2021) notes that the transitional government has “achieved significant progress toward a comprehensive peace in Sudan”.

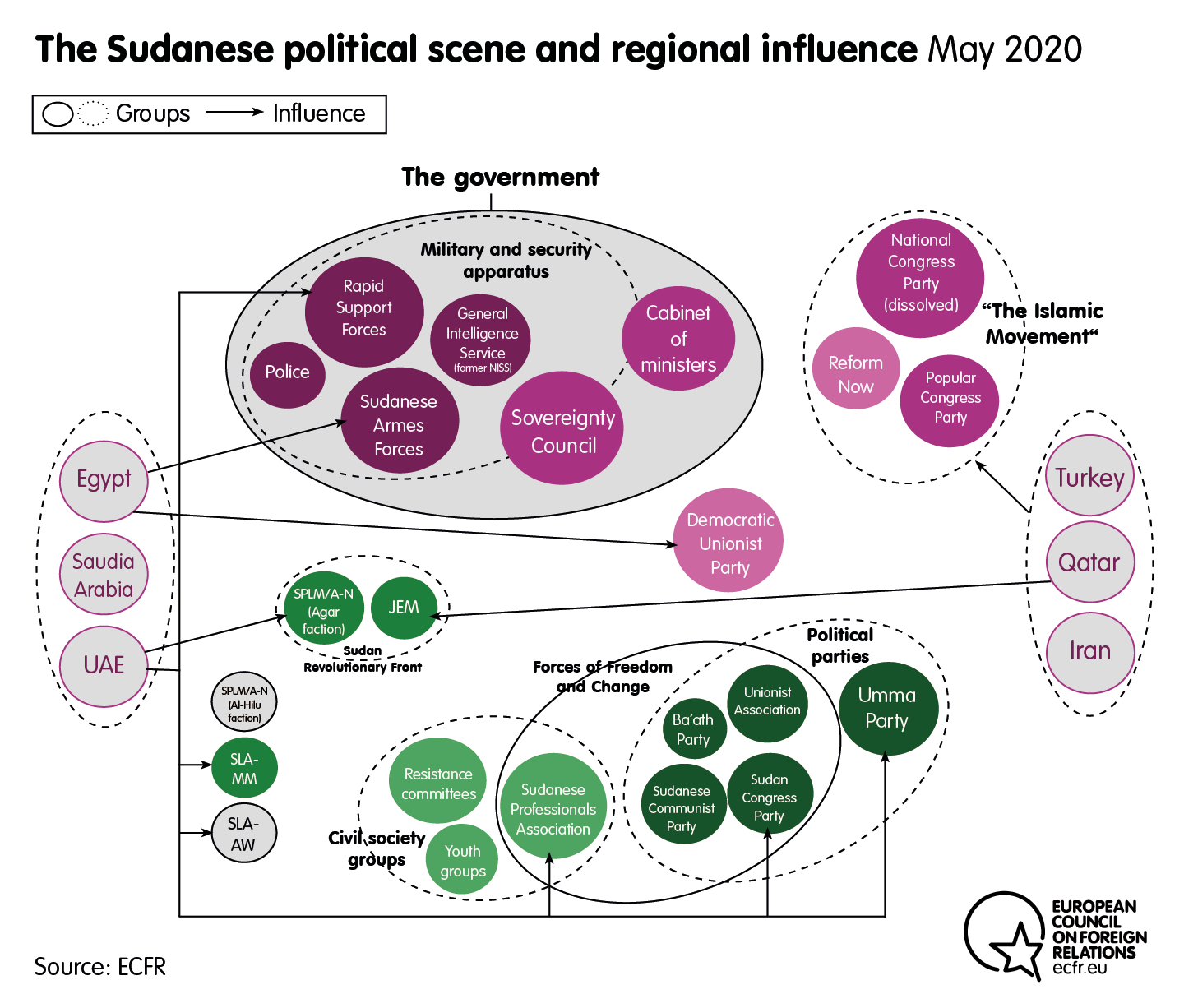

The Sudanese political scene and regional influence, May 2020

Source: Gallopin 2020

The constitutional charter signed in 2019 acts as the guideline for the transitional period (ConstitutionNet 2021). The previous regime’s kleptocratic grip on power was apparent to both domestic and international observers. While the draft constitutional charter sets out broad goals, including reducing corruption and recovering assets, it is worth noting that endurance and commitment will be needed to establish legal mechanisms and institutional practices to bring about systemic change (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020, 31; Schütte 2020). Freedom House (2020a) notes that the civic space is gradually “opening to individuals and opposition parties”. However, the report mentions that several players from the previous regime, known for its corruption and human rights abuses, remain influential and hold positions in the current transitional government. Such actors have also not made their commitment to political freedoms and civil liberties explicit (Freedom House 2020a).

The separation of South Sudan from Sudan in 2011 resulted in several economic challenges. The area of maximum impact came from the loss of oil revenue that accounted for more than half of the Sudanese government's income and 95 per cent of its exports (World Bank 2021a). In the past, political, and economic corruption have been the main obstacles to using Sudan's remaining available resources optimally (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020, 31).

In the Sudanese context, a transition from authoritarian rule to democracy would involve the current transitional government to address the country's continued economic crisis (Marsden 2021). An International Monetary Fund (IMF) Staff Monitored Programme (SMP) report notes that during the al-Bashir era, the provision of fuel subsidies resulted in widespread smuggling which presented a sizeable setback to the budget, leading to a deficit that had to be covered by printing money, and ultimately prompting high inflation. Currently, there are ongoing economic reform programmes which have been introduced to induce stability and create opportunities for more social spending, including “removing fuel subsidies, unification and liberalisation of the exchange rate, and an increase in electricity tariffs” (Marsden 2021). With respect to the negative impact of subsidy cuts, it is planned to be softened by a Family Support Programme, which is a social safety net project that plans to support 80 per cent of the population with cash payments. This scheme is based on significant donor support, with ongoing efforts to roll it out and expand access (Marsden 2021).

Sudan has been experiencing unprecedented challenges due to the Covid-19 pandemic (World Bank 2021b). The economic impact of the pandemic includes the increased price of essential foods, rising unemployment, and falling exports. Moreover, restrictions on movement make the financial situation worse, with commodity prices soaring across the country (World Bank 2021a). The country’s annual inflation jumped to 330.78 per cent in February 2021 (Al Jazeera 2021). As a result, several regions in Sudan had to declare states of emergency following violent protests against a rise in food prices in the first quarter of 2021 (Salih 2021). In such a context, an Enterprises Survey by the World Bank, and the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) highlights losses and economic fragility among Sudanese enterprises (World Bank 2021b).

It ought to be noted that Sudan’s political climate is in an evolutionary state with regular developments taking place, and this dynamic scenario may lead to changes that may not be adequately captured in reports available in the public domain. An IMF report (2020) notes that the analysis of governance performance, as well as corruption in Sudan, requires a contextual understanding of (Akanbi et al. 2020, 4):

- the innate fragility of the Sudanese state,

- its limited institutional capabilities,

- shortage of reliable and up-to-date data,

- an overall atmosphere of opacity.

All these factors in turn, contribute to weak governance and make the effects of corruption severe (Akanbi et al. 2020, 4).

Extent of corruption

Sudan ranks 174 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) with a score of 16/100 (Transparency International 2021). The country’s scores have improved by 3 points since 2019 (Transparency International 2021).

The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) (2020) accord the following scores in percentile rank to Sudan. Percentile rank showcases the country's position among all nations under the aggregate indicator, with 0 relating to the lowest position and 100 to the highest (World Bank 2020):

|

Indicator |

2018 |

2019 |

|

Control of corruption |

5.8 |

7.7 |

|

Government effectiveness |

4.3 |

5.3 |

|

Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism |

6.2 |

6.7 |

|

Regulatory quality |

3.8 |

3.8 |

|

The rule of law |

10.6 |

10.6 |

|

Voice and accountability |

3.0 |

5.4 |

The 2020 TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix places Sudan in the “high” risk category, ranking it 167 out of 194 surveyed countries with a risk score of 66 (TRACE International 2020).

Forms of corruption

Grand corruption

The previous Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Sudan (2020) highlights the state capture during al-Bashir’s rule. The erstwhile regime was marked by extensive neopatrimonialism, in which portions of the state apparatus were handed over to cronies, family and political supporters at the cost of the public interest. De Waal (2019, 12) refers to the pre-revolution political system as a “collusive oligopoly posing as a centralised authoritarian kleptocracy”.

With the advent of the transitional government under the TSC, the Empowerment Elimination, Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee is dismantling NCP's kleptocratic networks (Dabanga 2020; Dabanga 2021b). However, it ought to be noted that several key players from pre-revolution times, including General Dagalo, popularly known as Hemeti, still occupy critical positions in the Sudanese governance context (Freedom House 2020; Dabanga 2021b). As mentioned later in the section on military-owned businesses, Hemeti and his paramilitary group of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) maintain tight control of several key sectors of the economy, and these businesses are shrouded in opacity. The absence of transparency within the top rungs of government and business is historically known to trigger grand corruption in the Sudanese setting (Elamin 2019).

GAN Integrity (2021) reports that political interference is common in business operations, and corruption in public procurement, land administration, customs, tax administration, and the judiciary is rampant.

Petty corruption

Sudan continues to be plagued by petty corruption (GAN Integrity 2019). The police are significantly affected by accusations of corruption. The police have the authority to issue on-the-spot fines to those breaking traffic rules. Fines range between SDG50 (US$8) and SDG 100 (US$16). Such a practice is designed to support the courts by reducing their burden. However, it ends up resulting in frequent abuse by officers who use this authority to regularly demand bribes from violators to forgo such fines. A significant cause for this is that police officers are poorly paid, and, reportedly, many extort bribes to supplement their income (SDFG 2016).

Facilitation payments to gain access to public services and utilities is also commonplace. Obtaining licences, getting water and electricity connections often require bribes (GAN Integrity).

For a complete overview of the forms of corruption pre-2019, please refer to the previous Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Sudan (2020)

Focus areas

Military-owned business

The business climate in the country is known to be riddled with systemic corruption as a legacy of the NCP rule (Ardigo 2020, 5; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020, 16). During the al-Bashir era, most investors in Sudanese companies were linked either to the government or to military groups operating in the country (De Waal 2019, 18). Sudan has several so-called “grey companies”, which are government-owned/military-owned semi-public entities financed with public funds, but which were earlier “entrusted” to individuals (mostly Islamists) to run them on behalf of the NCP (Baldo 2018; Ardigo 2020, 7).

In the past, such an extensive system of crony capitalism ensured that such state-owned grey companies received preferential treatment to access hard currency, as well as lax regulation and oversight. In addition, this led to many of the companies not favoured by the then incumbent forces to resort to “any number of fraudulent procurement practices, such as substituting inferior and cheaper products; false invoicing for strategic goods allegedly procured; paying kickbacks to foreign suppliers and government officials awarding contracts; and collusion with other companies competing for government contracts” (Baldo 2018).

According to Finance Minister Ibrahim al-Badawi, currently, such grey companies, which are often military-run, dominate the business climate, but the profits, which are estimated to be around US$2 billion annually, do not reach the treasury (Creta 2020). Several civilian politicians view the military’s opaque business activities as “inappropriate", adding that their "profits are not included in the state budget” (Reuters 2021).

De Waal (2019, 16) points out that a cause of the business structure being this way is that the principal sources of political finance “lie in the areas of dramatic growth (gold and mercenary work) and the network of corruption around crony capitalism and the residual oil rentierism”.

De Waal (2019, 20) also opines that a critical factor is that Sudan's economy has not developed despite widespread acknowledgment of the challenges of corruption, rentierism and macroeconomic imbalances, along with a pressing need to address the economic crisis. For example, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) under the control of General Hemeti appear to have only further increased their authority on the gold trade as one form of business (De Waal 2019, 20). The RSF is the same paramilitary group that stands accused of the Khartoum massacre in 2019 (Al Jazeera 2019). Currently, the income from gold mining and the taxes on military-owned companies are not included in the budget (Dabanga 2021).

A collection of leaked documents obtained by Global Witness shows that Hemeti and the RSF control a significant part of the Sudanese gold industry (Global Witness 2019). These documents provide a glimpse into the RSF's financial networks providing evidence of the use of various front companies and banks based in UAE and Sudan (Global Witness 2019). Hemeti's brother Abdelrahim Hamdan Dagalo and Abdelrahim’s two younger sons are the owners of the El Junaid gold company. Abdelrahim is commonly recognised as the deputy head of the RSF, and El Junaid and RSF are allegedly “deeply intertwined”. An interview of an anonymous RSF officer with the BBC revealed that “an Abdelrahim Dagalo” had given the “order to clear the Khartoum sit-in.” However, this allegation could not be corroborated by the BBC (Dabanga 2019). Two other UAE based front companies – GSK (an information technology and security firm) and Tradive General Trading LLC are used by the RSF. Tradive is known to be channelling millions into and out of RSF accounts, allegedly as a means to partially cloud the militia's activities, El Joney Hamdan Dagalo, Hemeti's brother, is Tradive's beneficial owner (Dabanga 2019; Global Witness 2019).

The leaked bank documents seem to demonstrate that the RSF have an account with the National Bank of Abu Dhabi, which is currently a part of First Abu Dhabi Bank. This points to the financial autonomy of the RSF, suggesting that the paramilitary force's financial control does not lie with the military or the civilian components of the power-sharing Sovereign Council (Global Witness 2019).

The reason such a setup matters is that the RSF tend to justify their control of various companies by claiming that that the profits go towards the general welfare of the Sudanese people. For example, the RSF were rich enough for Hemeti to pledge over US$1 billion to support in stabilising the Sudanese Central Bank after the economic crisis and protests, which ultimately lead to the overthrow of the erstwhile regime in 2019. At that time, Hemeti claimed: "We put US $1.027 billion in the Bank of Sudan… the funds are there, available now” and that the RSF “supported the state at the beginning of the crisis by buying the essential resources: petrol, wheat, medication”. He went on: “People ask where do we [the RSF] bring this money from? We have the salaries of our troops fighting outside [abroad] and our gold investments, money from gold, and other investments” (Dabanga 2019).

Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok has criticised the country’s military over its vast business interests, saying that, “every army in the world invests in defence companies,” however, “it is unacceptable for the military and/or security services to do so in productive sectors, and thus compete with the private sector” (Al Jazeera 2020). Apart from the aforementioned gold sector, vital areas such as rubber, meat exports, flour and sesame are deemed to be heavily controlled by the military. Varying reports find that around 250 companies are under military control (Al Jazeera 2020). However, our conversations with activists suggest that the number of military-owned companies can be close to 400 in reality. Such companies are exempt from paying tax, and they currently operate in total opacity (Al Jazeera 2020). There are no concrete plans of transferring such companies to the government, according to the head of the Sovereign Council, army chief General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, adding that he is only willing to have such military owned firms pay tax (Al Jazeera 2020). Hamdok has stated that the government has control over only 18 per cent of the state's resources. It is a priority for Hamdok to return companies belonging to the security sector to the government (Al Jazeera 2020).

Joseph Siegle, director of research at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, opines that the end to such military-owned companies is particularly crucial for creating additional space for a competitive private sector to grow, stimulating productivity, and generating employment. Siegle adds that political stability and improvement of overall security in the Sudanese context requires that military leaders be financially accountable to the elected civilian leadership (Al Jazeera 2020).

Recently, the Defence Industries System, one of Sudan's most prominent military companies, reported its intention to separate its civilian and military wings. Jibril Ibrahim, the Minister of Finance and Economic Planning, opines that the company ought to pay taxes and be transparent in terms of its structure and operational plans, like any other Sudanese private sector business (Dabanga 2021).

However, to increase foreign investor confidence, further reforms are needed (Marsden 2021). Government and military officials holding direct and indirect stakes in many enterprises create a system of patronage and cronyism, which distorts market competition to hinder the functioning of foreign firms without political connections (GAN Integrity 2021). Moreover, with court systems, tax, and customs administrations, as well as public procurement posing significant corruption risks, foreign companies are wary of investing in the country (GAN Integrity 2021). Curbing such military control in business can thus play a vital role in boosting the current Sudanese economic scenario (Marsden 2021).

Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee

With tackling corruption being made one of the top three priorities of the transitional government, there is measured optimism in the international community about such actions translating on the ground (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020). Nevertheless, Sudan's Empowerment Elimination, Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee established by Sudan's Draft Constitutional Declaration and controlled by the transitional government is tasked with tracking and retrieving government money stolen by operatives of the defunct regime under their notorious embezzlement drive known as “tamkeen”77dfde6ab0fb or empowerment (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020; Suda Now 2020). It is due to operate until the end of the transition period (Abdelaziz and Eltahir 2021).

The Committee has played a vital role in breaking the NCP’s grip on the political scene and state resources. However, many officials linked with the former regime are still deployed at the state and local levels (Dabanga 2021b).

According to the 2020 law that led to its creation, the Committee has the authority to (Asharq Al-Awsat 2021):

- abolish public positions

- terminate the service of officials who obtained jobs through nepotism

- dissolve profit and non-profit organisations

- request reports and information from state institutions

- summon individuals to provide information

- seize bank accounts of persons, institutions, and companies with the intent of dismantling the former regime

At the time of al-Bashir's arrest, “US$351 thousand, €6.7 million, £5.2 million and SDG5 billion packed in bags designed for maize” were seized, and in December 2019, the former president was charged with two years house arrest for corruption (Schütte 2020). The status on Bashir currently is that he is to be handed over to the International Criminal Court (ICC) on alleged charges of war crimes in the western Darfur Province (Amin 2020).

Activists reveal, however, that such proceeds of corruption found upon al-Bashir’s arrest are merely the tip of the iceberg, with various assets being stashed by NCP kleptocrats. Such a context gave rise to the support that the Committee received from the general public and civilian leaders (Dabanga 2020).

The 18-member Committee, also known as the Tamkeen Removal (Empowerment Elimination) Committee, is made up of two members of the Sovereign Council5eb27c605f10 and representatives of government ministries, such as ministries of defence, interior, justice, finance, federal rule, the paramilitary RSF, the general intelligence, the political and social Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) that led the revolution against the Bashir rule and the office of the Attorney General (Suda Now 2020).

The Committee has already succeeded in bringing huge sums back into the state treasury (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020). Salah Manaa, the spokesperson for the Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee, puts the early estimates of the confiscated proceeds of corruption in the form of cash, shares in companies and real estate at US$3.5 billion to US$4 billion (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020). Wagdi Salih, another member of the Committee, has said it handed over more than US$1 billion to the ministry of finance and US$400 million to the ministry of religious affairs and endowments (Abdelaziz and Eltahir 2021). To tackle corruption in local contexts, branches of the commission have been set up at the state/provincial level as well. (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020). The Committee also dissolved the Islamic Da'awa (Call) Organisation and transferred its assets to the finance ministry, a decision considered by observers as a substantial blow to the financial might of the Islamists as the organisation was known to run the state from behind the scenes (Suda Now 2020). The board of the Central Bank was also dissolved (Suda Now 2020). So far, the Committee has seized more than 50 companies and 60 organisations, 20 million square meters of residential property and 420,000 hectares of farmland. Among other assets recovered are factories, hotels, schools, and a golf course on the outskirts of Khartoum (Abdelaziz and Eltahir 2021).

Another seizure is that of Tayba, a broadcaster that Bashir had financed and which the Committee said had broadcast content supporting groups including the Muslim Brotherhood and Boko Haram. Tayba's infrastructure is said to be more advanced than that of the national broadcaster. It will now be used to launch new channels in Sudan (Abdelaziz and Eltahir 2021).

At the individual level, the Committee has confiscated properties from Abdelbasit Hamza - a prominent figure in the Islamist business domain, former minister of foreign affairs - Ali Karti, former police chief - General Mohammad Najeeb, and former minister of defence - General Abdelrahim Mohammad Hussein. The Committee has also dismissed 109 ambassadors and diplomats from the ministry of foreign affairs, 651 employees in different government bodies, and 98 legal counsellors from the ministry of justice who had been hired without appropriate qualifications (Suda Now 2020).

The finance minister reports that retrieved sums have boosted the national budget with SDG128 billion (around US$280 million). With respect to spending the retrieved money, Committee member Mohammad Alfaki said that the funds will help in the pay increase of civil servants and the establishment of the sovereign fund, which will be set up to support development, boost the educational and health services and stabilise the economy (Suda Now 2020).

Despite its popular mandate, it ought to be noted that the Committee is a political and not a legal body (Dabanga 2020). The Committee also faces criticism for applying “selective justice” after it removed hundreds from the civil service “without proper explanation or [an] appeal process” (Abdelaziz and Eltahir 2021). Some critics reportedly view the Committee as a “means for easy political point-scoring by a government struggling to manage an economic crisis, while others are concerned about what they see as a shaky legal framework”. Several members of the al-Bashir government who engaged in bribery during his rule have escaped scrutiny; others are a part of the active political life, even having roles in the transitional government. They include senior security officials such as General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemeti), who sold the services of his RSF troops to foreign powers for use in the ongoing civil war in Yemen. Hemeti's ascent to high office was assisted by a personal fortune gained through “violently-acquired gold mining and smuggling” (Freedom House 2020a).

A better approach with respect to the Committee, according to Mohamed Abdelsalam, dean of the University of Khartoum law school, would have been to establish a group of independent commissioners, rather than politicians, who are able to apply the law equally to every individual. An appeals commission, as well as a judicial tribunal charged with reviewing the Committee’s decisions, have yet to convene (Abdelaziz and Eltahir 2021).

The constitutional declaration of 2020 recommends the creation of an independent anti-corruption commission. While a timeline for the commission's creation is yet to be announced, Sudan's transitional parliament has approved the Anti-Corruption National Commission Law after removing all the provisions that contradict the articles stipulated by the Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee. The primary purpose of the Anti-Corruption Commission would be to counter corruption in the country (i.e., after the overthrow of the NCP in 2019), whereas the funds recovery Committee is tasked with dealing with corruption in the Bashir era (i.e., pre-2019). The National Legislature has said that there would be no conflict between the roles of the commission and the dismantling Committee (Asharq Al-Awsat 2021). However, our conversations with activists working on the ground reveal that challenges and constraints may emerge from having two bodies tasked with the role of anti-corruption enforcement.

Schütte (2020) cautions on the effectiveness of such types of commissions in implementing anti-corruption measures in post-conflict settings and adds that often what is required is a precise mandate, operational independence, and sufficient resources to bolster the effectiveness of anti-corruption commissions, as broad mandates, few resources, and political intervention have rendered such bodies ineffective in several cases.

Legal and institutional framework

Prior to the 2019 revolution, Sudan’s government was known to make superficial efforts to counter corruption. During al-Bashir’s “war on corruption”, several bankers and businesspersons were targeted and presented to the public as the reason for Sudan’s economic predicament (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020, 11). However, it can be said that such an exercise had more to do with cleaning up images than fighting corruption as corrupt public officials and political actors were not held accountable or prosecuted when they broke the law (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020, 11; Creta 2020).

In such a context, experts opine that curbing corruption in Sudan requires more than a new law or commission. Lasting change would be dependent on active enforcement mechanisms and substantial political will (Creta 2020).

Legal framework

It was a challenge to meaningfully address corruption, under Bashir's rule, in part due to the administrative setup of the country. Even though Sudan has signed and ratified conventions such as the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC), their implementation remains weak (Sunjka 2021). While the construction of a new legal framework for anti-corruption is underway, the transitional government is yet to make substantial headways in tackling corruption. Systemic corruption from the Bashir regime continues to undercut ongoing programmes for change (Sunjka 2021).

For a detailed overview of the anti-corruption legal framework as it stands, please refer to the previous version of the Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Sudan (2020). This paper provides new additions as well as updates in legal areas that have witnessed changes.

Even after the 2019 revolution, Sudan’s legislative framework pertaining to anti-corruption is not very comprehensive and lacks enforcement (GAN Integrity 2021). One of the issues being addressed currently is the manner in which corruption is defined in the Sudan Penal Code of 2003, including attempts of corruption, bribery, and money laundering (Sunjka 2021).

Despite provisions requiring disclosure of wealth by public officials, and laws against bribery, Sudanese elites have routinely enriched themselves and targeted opponents by exploiting the inherent weaknesses of the existing system and relying on their clientelist networks. Simultaneously, unemployment and inflation rates have gone up, while the economy remains in crisis (Sunjka 2021).

The Council of Ministers and transitional parliament recently approved the legislation for the anti-corruption commission (ACC). However, Sunjka (2021) notes that the approval of the law is not an end in itself. The previous section on the Anti-Corruption and Funds Recovery Committee highlights the challenges in the setting up and functioning of the two anti-corruption bodies.

Sunjka (2020) notes that, while addressing corruption is a top priority for the transitional government, undoing the harms of three decades of authoritarian rule requires drastic changes. A crucial area that the administration needs to focus on, according to Sunjka (2021), is to provide a new whistleblowing mechanism for citizens to hold the government accountable, which ensures that citizens are safely able to report corruption. When it comes to tackling and preventing human rights violations related to corruption, sensitivities around tensions between religious and ethnic groups ought to be kept in mind. In essence, Sunjka (2021) states that a significant overhaul of the country's governance structure is required to successfully address corruption. Strategies for this exercise ought to include dismantling the established methods for corruption that have given public officials the means to enrich themselves over the years (Sunjka 2021).

Currently, the Cybercrime Act is allegedly being used to stifle dissent, with a proposed Security Bill also being viewed as an attempt to legally restrict freedom of expression (Sudan Information Service 2021). The draft Internal Security Agency Bill (Security Bill) has provoked criticism from across Sudan’s political spectrum on the grounds that it grants authorities the right to detain individuals without a court order or warrant for two days, which acts as a reminder of the al-Bashir regime (Dabanga 2021c). Legal analysts suggest that Sudan’s judicial system also lacks the resources and political will to find justice for victims of protest crackdowns. In an interview with Newlines Magazine, Nabil Adib, the human rights lawyer who leads the Committee to investigate the June 2019 massacre, said that Sudan would be "destabilised" if he publishes the Committee's findings (Sudan Information Service 2021).

Institutional framework

With respect to the anti-corruption bodies, Acting Attorney General of Sudan, Mubarak Mahmoud Osman, commented that since his country is one that understands the consequences of corruption, it also sees value in properly rebuilding its institutions. Osman has stated that various courts are tackling corruption cases, with high profile members of the former regime, including the al-Bashir, being investigated. Osman added that the government has pushed for an asset recovery law and is revising rules regarding procurement while also implementing counter-terrorism legislation. Sudan is deemed to be using the UNCAC as the bedrock of its anti-corruption policies. However, he cautioned that the country still “needs technical support” in setting up and running the revised legal infrastructure (UNGA 2021).

The General Intelligence Service (GIS), which is set to work on counterterrorism and anti-corruption efforts, has replaced the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) known for harassing, detaining, and targeting al-Bashir's opponents (Freedom House 2020a).

A new body known as the Council of Partners for the Transitional Period was created by including a new article (Article 80) into the interim constitution. The body comprises the parties of the Juba peace agreement, namely the prime minister, the military, the FFC and the rebel groups. The council is to handle the main political issues that may come up during the transition period. A significant governance risk identified by critics concerning the council is that its authority can ultimately supersede the other governance bodies set up under the transitional government (Freedom House 2021).

The interim constitution envisions a comprehensive legal reform, including the establishment of an independent judiciary, to replace the politically influenced system from the authoritarian era. After large scale protests for accelerated judicial reform, the first few appointments were announced in late 2019, amongst whom was the first female chief justice of the country. A different system of military courts has also been established to deal with members of the armed forces and security services (Freedom House 2020a).

The politically biased National Election Commission of the NCP era was supposed to be replaced by a new one per the interim constitution. However, neither a framework for elections nor a new body of members has been formed (Freedom House 2021).

A new public prosecutor was appointed in 2019, as required by the interim constitution. One of the first cases prosecuted by the office was the case of al-Bashir itself. Later on, 27 members of the security forces were prosecuted by the office for their involvement in the detention and murder of a schoolteacher; ultimately, the conviction led to death sentences in December 2019 (Freedom House 2020a). While the right to due process is a requirement according to the interim constitution, there is also a provision that grants the government emergency powers to suspend parts of the document. Despite such a provision presenting a risk for abuse, the FFC has defended the measure saying that it is needed in the current Sudanese climate of ongoing tensions and instability, adding that the provision may be necessary to complete the prosecution of former regime members (Freedom House 2020a).

For a complete list of institutions tasked with good governance and anti-corruption responsibilities, please refer to the previous version of the Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Sudan (2020).

The head of the Friedrich-Ebert-Foundation’s office, a democracy promotion organisation, in Sudan opines that Sudan needs sustained anti-corruption programmes that result in "efficient and effective administration" of services. Administrative reforms which would result in the lowering costs of essential services could go far in addressing one of the significant causes of unrest that threatens stability in Sudan (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020).

Despite considerable support for reducing corruption, Sudan faces an uphill battle (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020). Kinda Hattar, Regional Advisor of the Middle East and North Africa at Transparency International, observed that, while there may be "changed faces" in the Sudanese administration, the country is yet to change "systems that allow the corrupt to come back" (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020).

Dismantling corruption in Sudan will thus require a “180-degree approach”, including improving the legal mechanism, the judicial system, and other institutions that have been abused by corrupt actors for decades. Simultaneously, Sudan's civic space must be strengthened to allow citizens to hold the government accountable without fear of retribution (Maclay and Elmahdi 2020).

Other stakeholders

Media

Historically, journalists have faced a hostile environment in Sudan.National newspapers were frequently closed, and journalists were detained without charge when protests began in 2018. The NISS, before its closure, interrogated Shamael al-Nur, a journalist at the Al-Tayyar newspaper, after anti-government material was posted on its Facebook page in 2019. The TMC, akin to the earlier regime, also exhibited repressive tactics during its brief time in power. It closed down the Sudan bureau of Al Jazeera in May 2019 (it was restarted in August) and detained Sadiq al-Rizaigi, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Al-Sasha and president of the Sudanese Journalists' Union (SJU) without an official reason (Freedom House 2020a).

While the current TSC has abstained from the most oppressive methods used by the al-Bashir government, journalists continue to condemn its activities, such as its decision to close trade union organisations under the guise of them being associated with the old regime (Freedom House 2020a).

The RSF controlled by Hemeti continues to target journalists since the transitional government came to force (Freedom House 2020a). Activists are also being charged in Sudanese courts for spreading “false news” under the Cybercrime Act of 2018. Khadeeja al-Deweihi, a human rights worker, was charged under the act for a Facebook post discussing the health situation in Sudan. Al-Deweihi was asked to appear at the Office of the Prosecutor in late 2020, where she was asked about her partisan views and her engagement with the Communist Party of Sudan (Sudan Information Centre 2021). By the end of 2020, more than 80 national media workers were let go owing to their alleged affiliation with the NCP and al-Bashir (Freedom House 2021).

The NISS allegedly monitored private communications without oversight or authorisation during the NCP era, and the government was known to use defamation laws to prosecute social media users that criticised it. Internet access was restricted in sporadic episodes during the revolution and even after the TMC took power in 2019. The Internet was unavailable for most of June 2019, which coincides with the time of the RSF's massacre of protesters in Khartoum and the popularity of the #BlueForSudan Twitter campaign calling for the formation of a civilian government (Freedom House 2020a).

With the right to privacy being assured to citizens under the interim constitution, the surveillance state that was characteristic of the former regime is being undone under the current administration (Freedom House 2020a).

According to Reporters Without Borders, most of the newspapers are still affiliated with supporters of the former regime. Moreover, fake news machinery such as the Cyber Jihadist Unit, which was to observe trends and keep track of the online activities of journalists and activists, still exists, and continues to spread false information on social media in order to undermine the transitional government (Reporters Without Borders 2021).

While the interim constitution guarantees press freedom and internet access, older draconian laws against the media remain to be dismantled. For a free and independent press culture to take hold after 30 years of oppressive rule, it needs support, protection, and training (Reporters Without Borders 2021).

At a Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) forum held in February 2021, pro-democracy reporters started a new alliance dedicated to investigating corruption in the country. Known as the Journalists for Anti-Corruption Initiative, its founding has provided an opportunity to discuss the challenges journalists face while exploring the country’s corruption problems (Schmidt 2021). Such alliances may be necessary given the context at hand. For example, a CIPE report notes that there are few politically independent journalists, most of whom are not trained to undertake anti-corruption investigations, and those who have the expertise often lack security and protection (Schmidt 2021). Another significant challenge is the lack of reliable public and open data about government functioning. Beneficial ownership information is also limited.Although Sudan has a freedom of information law, a journalist at the CIPE forum reported having to take a government institution to court to receive general information about its functioning and operations (Schmidt 2021).

The country ranks 159/180 in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders 2021). Sudan is rated “not free” in Freedom on the Net, with a score of 30/100 according to Freedom House (2020b).

Civil society

Under al-Bashir, international and domestic non-governmental organisations (NGOs) faced serious difficulties or were prevented from operating altogether. The transitional government aims to loosen the restrictions on civil society activities. Under the new transitional governance, NGOs expelled by al-Bashir will be allowed to continue humanitarian operations in conflict-affected areas (Freedom House 2020a).

While the civic space is opening up in the country, activists opine that there is limited anti-corruption expertise. Nevertheless, a few organisations contributing to good governance and anti-corruption activities are the following:

The Al-Khatim Adlan Center for Enlightenment (KACE) aims to "develop, consolidate and spread the culture of peace and democracy". It runs programmes on increasing dialogues between various civil society actors, government bodies and private sector organisations. Its campaigns include civil society leadership training in governance, awareness against institutionalised violence against women and educational reform for plurality and peace (KACE Sudan 2021). KACE hosts the Sudan Anti-Corruption Resource Center and is supported by the Center for International Special Projects, operating within the framework of the Rapid Response to Democratic Opportunities project (SARC 2021). It seeks to organise, convene and support locally driven anti-corruption reform efforts and build effective governance in Sudan (SARC 2021).

The Sudan Democracy First Group (SDFG) emerged to promote "democracy in its intersection, with peace, justice, and balanced development". It currently works in four areas, namely (SDFG 2021):

- civil society in areas of conflict

- advocacy aimed at solidarity and protection

- reforms aimed at governance and institutions

- civic engagement for peace building

Sudan Innovation and Entrepreneurship Network (SIEN) is a network of start-ups and entrepreneurs in Sudan whose goal is to collectively reform and develop the entrepreneurship and innovation industry in the country (SIEN 2021).

- Empowerment (tamkeen) is the term with which the ousted government supported its associates in state affairs by granting them extensive privileges, including government positions and control of various companies (Dabanga 2021b).

- The transitional ruling military-civilian body established after the ouster of Bashir in 2019.