1. Introduction

In the ongoing struggle against corruption and related offences, many countries have established specialised anti-corruption institutions, distinct from the regular institutions of justice. The most familiar of these special bodies are the so-called anti-corruption agencies (ACAs), which typically wield some form of investigative and/or prosecutorial power. Scores of countries have ACAs of some kind, and there is already a great deal of research and commentary on ACA models.0f373eae72cf Considerably less attention has been paid to another form of anti-corruption specialisation, namely specialised anti-corruption courts. Though these are not as ubiquitous as ACAs, many countries have created a special judicial body, division, or set of judges to focus, exclusively or substantially, on corruption-related cases. Many other countries are currently considering whether to establish such special courts. Yet while there is a body of literature that discusses judicial specialisation more generally,733178002058 there is little systematic, comparative analysis focused specifically on specialised anti-corruption courts.

In 2016, we took a first step towards filling that gap by presenting a comparative overview of the 17 specialised anti-corruption courts that existed at that time, with particular attention to the rationale for their creation and to basic design choices.901343dd8f353208ae671294 The original U4 Issue was based on a review of secondary sources for a broad range of countries and on interviews with key stakeholders in five countries that have specialised anti-corruption courts of some kind: Indonesia, Kenya, the Philippines, Slovakia, and Uganda. Four country case studies based on this fieldwork were published in June 2016.05ea1b80cda2 Since the publication of the original overview, the anti-corruption court in Bulgaria has ceased to exist, while the one in Afghanistan is apparently defunct as well. The court in Mexico has not become operational, although enabling legislation has been in place for more than five years. Meanwhile, at least nine more countries have established specialised anti-corruption courts.

This updated paper expands on and modifies our 2016 work in light of these developments. We have incorporated 13 additional courts in the analysis and categorisation, including three Eastern European courts that were not considered in the original paper. The design of the new courts in particular allows us to make minor adjustments to the categorisation of court designs by function, though we observe emulation and convergence more than any new models. The new courts align with rather than radically challenge the observations of our original study. As in that study, the current discussion is based on a general review of secondary sources and on in-depth case studies of selected countries. Here we examine four: Madagascar;932c09accd10 Ukraine;eba6f3c57c9f Zimbabwe;2f9e386a48df and Albania.c26049af541e

This update follows the original structure. Section 2 explains our working definition of a ‘specialised anti-corruption court’ and lists the countries with such institutions that we reviewed in our research. Section 3 discusses the three principal rationales for establishing a specialised anti-corruption court – efficiency, integrity, and expertise – and offers some preliminary observations about each. Section 4 turns to questions of institutional design, highlighting the diversity of existing anti-corruption courts and identifying some of the key design questions that anyone thinking of setting up or reforming such a court should consider. A brief conclusion summarises some of the main themes of the paper and calls for investments in data transparency and research to allow for more rigorous assessments of the effectiveness and impact of specialisation.

Like the original U4 Issue, this update does not attempt to put forward best practices or to systematically assess the performance of any existing court system. Such an analysis would be well beyond the scope of this paper, given time, space, and data limitations. In particular, the lack of any systematic baseline information continues to preclude a general assessment of whether specialisation has been a good or a bad thing. This Issue’s more modest goal is to provide an overview of different types of specialised anti-corruption courts and to highlight some of the key challenges and trade-offs that must be considered when designing such institutions.

2. Overview: Specialised anti-corruption courts and judges around the world

For purposes of this paper, we define an ‘anti-corruption court’ as a judge, court, division of a court, or tribunal that specialises substantially (though not necessarily exclusively) in the adjudication of corruption cases. Using this definition, our initial survey, conducted in 2015, identified 17 jurisdictions that had specialised anti-corruption courts at that time: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Botswana, Bulgaria, Burundi, Cameroon, Croatia, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Palestine, the Philippines, Senegal, Slovakia, and Uganda.

We have decided to omit Afghanistan’s anti-corruption court from this 2022 update as it is not clear whether has continued to exist in any form under the Taliban regime. Bulgaria’s Specialised Criminal Court was abolished by the Bulgarian Parliament in early 2022.

Meanwhile, nine more countries have established specialised anti-corruption courts since the publication of the original paper: Albania, Armenia, Madagascar, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the courts around the world, with functional courts currently operating only in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. The Americas do not have this level of specialisation on corruption cases. In Mexico, a 2015 constitutional amendment called for the creation of a specialised anti-corruption chamber in the Federal Administrative Court. Even though the amendment entered into force in 2017, judicial appointments were still stalled as of late 2021.5830893fee47

Figure 1. Anti-corruption courts in the world, 2022

Specialised anti-corruption courts: Albania, Armenia, Bangladesh, Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Croatia, Indonesia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malaysia, Montenegro, Nepal, North Macedonia, Pakistan, Palestine, the Philippines, Senegal, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe.

In addition, there are three borderline cases that we did not include in our list but that deserve brief mention.

First, Papua New Guinea’s National Court has created a ‘fraud and corruption track’, with streamlined procedures to expedite the processing of corruption cases. However, the judges presiding in these cases are regular National Court judges. Other than the special procedures, there is no meaningful institutional separation between this corruption track and the regular National Court. Thus, while the practice of creating special rules for corruption cases in the regular courts is itself interesting and worthy of study, Papua New Guinea’s approach does not really involve the creation of a special court to hear corruption cases.

Second, Brazil has created a set of federal-level special courts to deal with cases involving money laundering and related financial crimes. While money laundering is obviously closely intertwined with corruption, in the end we did not include the Brazilian special courts in our survey, in part because ‘core’ corruption offences, such as bribery and embezzlement, are not adjudicated in these courts.f5e6709d1245

Third, we have not included Tunisia’s special judicial chamber for complex economic and financial offenses, which was established in 2016 within the Court of Appeals in Tunis. The jurisdiction of this special unit is broad, including not only some bribery offenses but also tax, customs, foreign exchange, and banking crimes.d0c68a8f4a8f Because the court’s jurisdiction is defined in terms of complex economic crime rather than corruption as such, and we were unable to establish what percentage of the docket consists of corruption cases, we have not included it further in the analysis.

By contrast, we did choose to include countries where the specialised judge or court also has authority to adjudicate a set of non-corruption cases. These include Bangladesh, Croatia, and Slovakia, from the original paper, plus Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia, added in this update. We took this decision because these judicial bodies have a substantial focus on corruption cases regardless of their complexity (although with some jurisdictional limitations as regards the public profile of defendants), and because corruption cases make up a substantial part of their dockets.

In none of these cases do we claim to have made the ‘correct’ decision regarding classification. As is almost always true when one tries to define the boundaries of any category, there are some tricky borderline cases and judgment calls. But our objective in this paper is not to provide a conclusive definition and definitive list of anti-corruption courts. Rather, we hope to illustrate some of the most significant institutional design choices involved in setting up judicial institutions that will focus on corruption cases.

In most countries that have specialised anti-corruption courts, these courts were created by statute, though there are exceptions.91cd05f1a678 Specialised anti-corruption courts are a relatively new phenomenon. Although the oldest such court, that of the Philippines, was established in the 1970s, none of the other specialised anti-corruption courts identified in this study began operation prior to 1999, and most of them were established within the past two decades (often concurrently with, or following, the establishment of a specialised anti-corruption agency). The dates of establishment of the 27 operational anti-corruption courts that we reviewed are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Specialised anti-corruption courts by country and year established

|

Year |

Country |

|

1979 |

Philippines (pursuant to provisions in the 1973 Constitution) |

|

1999 |

Pakistan |

|

2002 |

Indonesia (substantially revised in 2009) |

|

2003 |

Kenya (substantially revised in 2016) |

|

2004 |

Bangladesh |

|

2006 |

Burundi |

|

2008 |

Croatia |

|

2009 |

Slovakia |

|

2010 |

Serbia (Organised Crime Department with jurisdiction in large-scale corruption cases; in 2016 Corruption Departments at High Courts were added) |

|

2011 |

Cameroon |

|

2012 |

Senegal (pursuant to authorisation in a 1981 statute) |

|

2013 |

Botswana |

|

2016 |

Madagascar |

|

2018 |

Sri Lanka |

|

2019 |

Albania |

|

2020 |

Zimbabwe |

|

2021 |

Armenia |

Although in many of the above countries the specialised anti-corruption courts have been entirely ‘home-grown’, in other cases the international donor community has played a significant role. Indeed, in a few cases the impetus to create a specialised anti-corruption court has been largely donor-driven. This was most evident in Afghanistan, where the international community (particularly the United States and the United Kingdom) pressured the Afghan government to move rapidly to create anti-corruption courts – both because corruption was viewed as a serious obstacle to economic development and security in Afghanistan, and because international donors were frustrated by the extent to which the funds they provided to the Afghan government were misappropriated.f8cb6d7e0796 Likewise, the creation of Nepal’s Special Court seems to have been at least partially a response to pressure from international donors concerned with substantial ‘leakage’ in donor-funded programs.68b4d9619954 In both of these cases, donors – principally the US and UK governments in the Afghanistan case, and principally the Asian Development Bank in the Nepal case – also provided extensive financial and technical support to the courts, both during and after their creation.

In Ukraine, civil society actors managed to enlist the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Union (EU), the World Bank, and other donors for the creation of the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) in 2018. The IMF and EU even made the establishment of the HACC a condition for financial assistance. The HACC has since received considerable support from various donor agencies for its capacity building and facilities.a972946905b5

In Albania, international stakeholders substantially influenced the establishment of the Special Courts against Corruption and Organised Crime. An expert group which devised the overall architecture of the reform included representatives of international service projects, and it modelled the new structure on existing anti-corruption institutions in Europe. In addition, the Venice Commission, a constitutional expert body of the Council of Europe, made several recommendations on the design of the court that led to adjustments. Essential to the success of the overall reform process in Albania has been its continued promotion by the EU and the United States, which have provided support through various initiatives. Crucially, Albania was granted EU candidate status in June 2014, but the start of accession negotiations was made conditional on sustained progress on justice reforms and actions to counter organised crime and corruption.dd8d44a92607

Even in many cases where direct donor pressure had relatively little to do with the decision to establish an anti-corruption court, international donors have been heavily involved in providing training, financial support, and other assistance for these institutions, often as part of general support to judicial reform. Examples of such donor support include, but are certainly not limited to, technical training provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to the Uganda High Court’s Anti-Corruption Division;5a940945831d USAID support for streamlining adjudication of corruption cases and creation of an electronic register of corruption cases in Serbia;46bbb235d29f training and refurbishment provided by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) to the Anti-Corruption Division of the High Court in Sierra Leone;7304b3aa618a training provided by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) for judges on Indonesia’s Tipikor courts and the Malaysian anti-corruption court;e239eec19c4a and both training and funding provided to Palestine’s Corruption Crimes Court by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the European Union Coordinating Office for Palestinian Police Support, and several bilateral donors.08229294a8ed

Clearly, although specialised anti-corruption courts are not as ubiquitous as ACAs, they are fast becoming an important part of the repertoire of anti-corruption reformers. There is a need to reflect critically on their potential justifications and drawbacks and to carefully consider how such courts should be designed. Section 3 focuses on the former issue – the ‘why’ – while section 4 turns to the latter question – the ‘how’.

3. Reasons for creating a specialised anti-corruption court

Court specialisation is a common phenomenon all over the world. Proponents typically emphasise that specialised courts can promote greater efficiency, often through streamlined procedures, as well as higher-quality and more consistent decisions in complex areas of law.0c8de50720e4 Consistent with this, Gramckow and Walsh find, in their review of international experiences with court specialisation, that specialisation can help the processing of complex cases that ‘require special expertise beyond the law, such as in bankruptcy, environmental, or mental health issues, or cases that must be handled differently to better reflect the needs of a particular court user group, such as business cases or family matters’.5e8c3a16f140 The arguments for specialised anti-corruption courts are similar, though these courts also have some distinctive features. While the reasons for the creation of specialised anti-corruption courts are varied, three stand out as particularly salient: efficiency, integrity, and expertise.

3.1. Efficiency

Perhaps the most common rationale for the creation of specialised anti-corruption courts is the desire to increase the efficiency with which the judicial system resolves corruption cases. Indeed, in most of the jurisdictions that have adopted a specialised anti-corruption court, the desire to speed up the processing of cases has been one of the main public justifications. This was true, for example, in Botswana,6d8ee43ecec7 Cameroon,307f00e467e8 Croatia,4d78430b868b Malaysia,8bf23a1e8fa3 Palestine,8377606af7b1 the Philippines,b37988f6661b Sri Lanka,70f18fa8207e Thailand,b8bc731c9ed2 and Uganda.3503bd2438d5

This is understandable. Many countries – particularly, though not exclusively, developing or transition countries – face substantial backlogs and delays throughout the judicial system. And while judicial inefficiency is undesirable in all cases, it may be especially pernicious with respect to anti-corruption cases, for two reasons. First, the urgency of making progress in the fight against corruption means that extensive judicial delays in dealing with corruption cases are particularly problematic, especially since such delays threaten to undermine public confidence in the government’s commitment and capacity to combat corruption effectively. Second, substantial delays in processing cases increase the risk that defendants or their allies may exert undue influence on witnesses, tamper with evidence, or take other action to interfere with the ordinary and impartial operation of the justice system. While such concerns are not unique to corruption cases, they are especially acute with respect to such cases.

How, exactly, is the creation of a specialised anti-corruption court supposed to increase the efficiency with which the judicial system handles corruption cases? There are three main mechanisms.

First, part of the logic is simply that a specialised court, which handles only corruption cases or similar offences, will have a more favourable ratio of judges to cases and will therefore be able to process cases more quickly. Besides improving the judge-to-case ratio, a specialised anti-corruption court may enable those overseeing the judicial system to assign more capable judges to corruption cases, further promoting their efficient resolution. While these factors sometimes help specialised anti-corruption courts process cases more quickly than the ordinary courts, this is not always the case. Many anti-corruption courts seem just as swamped as the regular court system, perhaps more so.

Furthermore, the judge-to-case ratio does not improve at all in those countries that do not limit their special anti-corruption judges to hearing only corruption cases. In Bangladesh, for example, although certain designated ‘special judges’ may preside over corruption cases, these judges also have to deal with regular cases and other (non-corruption) special cases. As a result, critics say, they remain overburdened and unable to ensure timely trials for corruption cases.64faa9d2e08c In the city of Rangpur, Bangladesh, as many as 226 corruption cases were reportedly pending in early 2021 because the position of special judge had been vacant for more than 18 months.0861564993c4 Similar criticism has been made with respect to thespecial ‘gazetted’ magistrates in Kenya, described in more detail in Box 1. One should also keep in mind that any improvement in the judge-to-case ratio for corruption cases, or the allocation of more talented judges to such cases, can come at the cost of diverting judicial resources from other areas of pressing need.

Box 1. The Kenyan experience with gazetting magistrates for corruption cases

In Kenya, the 2003 Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act (sec. 3) established a system for trying offences under that law, as well as other offences with which the defendant could be charged at the same trial. Under this system, the Judicial Service Commission can, through notice in the Kenya Gazette, appoint ‘as many special Magistrates as may be necessary’. The expectation was that these ‘gazetted’ magistrates would deal with corruption cases in a timelier fashion by developing special expertise for complex economic crime cases that often rely on electronic evidence. Having been gazetted was like being licensed to hear corruption cases; but while that license was based on experience and seniority, no special training or other capacity building was provided to these magistrates. Despite these shortcomings, the system expanded from the capital city of Nairobi, the initial location of just two gazetted magistrates, to all the counties. By 2015, about 30 active magistrates were gazetted to hear corruption cases, but those outside Nairobi were still hearing other cases as well.

The effectiveness of this system was undermined by the Kenyan practice of rotating magistrates every two years. Many corruption cases cannot be finalised within that time frame, due to capacity constraints as well as defendants’ ability to stall the process through all available legal means, such as by filing constitutional challenges that can take years to resolve. When a magistrate is rotated to a new post before the case is finished, either that magistrate has to travel back to finish the trial hearing or the case must be handed over to a new magistrate. Either alternative leads to additional delays (Director of Public Prosecutions 2014, 4).

In 2015, the system underwent changes, including the creation of an Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Division (ACEC) of the High Court at Milimani Law Courts in Nairobi (Munene 2015). As one of seven High Court divisions, the ACEC hears appeals from subordinate courts, but it is also a court of first instance for civil asset forfeiture. Such cases currently constitute the large majority of cases heard by the court. Another specialty of the ACEC is that it manages its own registry and can take over corruption and economic crimes filed with other High Court divisions (Kenya Gazette, vol. CXVIII, no. 153).

During the second half of 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic slowed down all proceedings, the case clearance rate at the High Court was 54%. The average time to determine a case (disposition) was 266 days, with 93% of cases resolved within a year. Milimani Magistrates’ Court, hearing first instance cases from Nairobi, had a clearance rate of only 44%; average time to disposition was 576 days, and only 14% of cases were determined within a year. Unfortunately, the publication of case statistics on the Kenyan judiciary’s website was discontinued after 2019 (Republic of Kenya Judiciary 2019).

Gazetted magistrates are reportedly still battling a backlog and delays caused by workload, absence of defence or witnesses, lack of court availability, and/or pending points of appeal at a superior court. The majority of corruption cases go on appeal at the High Court in Milimani, and these appeals seem to be processed with more efficiency, though they are increasingly in competition with the quickly growing number of civil forfeiture cases.

To address the delay in resolution of corruption cases, in February 2022 a specialised committee was established to examine bottlenecks and to advise the National Council on the Administration of Justice on how corruption cases can be moved expeditiously. This may include the development of practice guidelines to guide the conduct of trials handled by gazetted magistrates. Recommended practices may include pre-trial conferences where the trial schedule is set, issues are settled, and all parties including the magistrate, prosecutor, and defence attorneys participate.

The authors would like to thank the heads of the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Division of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Transparency International Kenya, Milimani Law Courts in Nairobi, and GIZ Kenya for sharing their experiences and insights during semi-structured interviews in August 2015. We thank the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission for providing follow-up information in November 2021 and August 2022.

Second, anti-corruption courts may streamline the procedures for handling corruption cases in various ways. For instance, as discussed in greater detail below, some anti-corruption courts are courts of first instance, with appeals going directly to the country’s supreme court, thus bypassing the usual intermediate appellate courts. Something like this structure is used, for example, in Burundi,9521c4c1b94c Cameroon,16f801f9acb7 Nepal,e99273bc6e8a Senegal,e01c8aa83b96 Slovakia,2f12b500399f and Sri Lanka.f5c15ceb3a2e

Botswana presents an interesting variant on this theme. There, as in many other countries, the regular lower courts lack the jurisdiction to resolve constitutional questions. In an ordinary criminal trial, when a defendant raises a plausible constitutional objection, the trial must be temporarily suspended and the case transferred to the High Court, which will resolve the constitutional question and return the case to the lower court. Because defendants in corruption cases are especially likely to make constitutional arguments, this feature of the Botswanan system was a frequent source of delay in those cases. Botswana’s chief justice therefore created the specialised Corruption Court as a division of the High Court, giving it jurisdiction over constitutional issues.4566d3a569a0 However, in Botswana corruption cases still begin in the magistrate courts; the special anti-corruption division of the High Court remains an appellate tribunal. As a result, the creation of the specialised anti-corruption division has not sped up case processing as much as proponents hoped.ec1d0efb1498

We see something similar in Uganda, where the Anti-Corruption Division of the High Court has managed to keep the average time to decision at first instance at about one year, despite deliberate attempts by accused persons to delay their trials by every possible legal means. Prior to 2010, if the defendant raised a constitutional objection, the trial would be automatically suspended and the issue referred to the Constitutional Court. However, an appendix to a Constitutional Court ruling in 2010 ended this practice. Now, before a purported constitutional objection is referred to the Constitutional Court, the Anti-Corruption Division must first decide whether the objection has sufficient merit.9b56a4ba8299

Third, in order to speed up the processing of corruption cases, many jurisdictions impose special deadlines on their anti-corruption courts. Examples include Cameroon,663781ab4491 Nepal,e9a3eac95ad2 Palestine,9f41296a42e2 the Philippines,a974642d2b30 and Indonesia.06e041697dac The deadlines vary a great deal across countries, in part because of other differences in the structure, function, and organisation of the courts. There also seems to be quite a bit of variation across countries in the degree to which the deadlines are observed in practice.

The Corruption Crimes Court in Palestine is notable for its especially tight deadlines. At least as a matter of formal statutory law, this court is supposed to hear any case brought to it within ten days and to issue a decision within ten days after the hearing, with an allowable postponement of no more than seven days.9ecf81af0a12 Of course, some may question whether these requirements are too demanding, not only because of the difficulty of meeting such short deadlines in practice – an issue discussed further below – but also because ten days may not be sufficient time to hear a case fairly and competently.

Malaysia provides another prominent (if less extreme) example. At the time Malaysia established its specialised anti-corruption courts, the average time required for a corruption case to make its way to final resolution was about 8.5 years.31d12cd5dc32 Malaysia therefore imposed a legal requirement that the anti-corruption courts process cases within one year (a requirement that does not apply to judges in the regular courts). In Malaysia, researchers found that roughly 75% of cases in 2012 were in fact completed within the one-year time limit.9357305854c68d8ab7e78f06

In contrast, anti-corruption courts in many other countries have struggled to adhere to the statutory deadlines. For instance, in the Philippines, the special anti-corruption court, known as the Sandiganbayan, is supposed to resolve each case within three months, but in practice cases could take close to a decade to resolve.8b01cd0db08c These extraordinary delays have prompted proposals for reform. A bill enacted in 2015 created two new divisions of the Sandiganbayan (bringing the total number of judges from 15 to 21), reduced the quorum requirements, and transferred cases involving smaller amounts of money to the regional trial courts.0d21633d952c This was followed by the introduction, in 2017, of new procedural rules that facilitate the efficient processing of criminal cases and prohibit several motions that have been abused to delay trial. In 2018 another reform gave the court the authority to serve subpoenas and notices electronically. Together these reforms led to a reduction in the average time of case disposition from eight years in 2016 to five years by 2019. During the pandemic the Sandiganbayan was one of the first courts in the Philippines to introduce remote hearings, and it has been able to keep the average case disposal time at around five years.f988767bcf26

The Sandiganbayan is not the only specialised anti-corruption court that has struggled with lengthy delays. Indeed, failure to comply with case-processing deadlines is more likely the norm than the exception. In Nepal, the Special Court is supposed to decide each case within six months of filing, and any appeal of a Special Court decision is supposed to be resolved by the Supreme Court within three months.f2d840523c9c In practice, however, cases take much longer, sometimes up to 11 years.122ec5f6cf3b In Pakistan, the National Accountability Courts are supposed to resolve cases within 30 days but have taken closer to 500 days on average.4379e61c927c

In general, although many specialised anti-corruption courts were created to improve efficiency in the processing of corruption cases, complaints about excessive delay in these courts are common in many (though not all) of the jurisdictions that have created them. In addition to the Nepal, Pakistan, and Philippines examples noted above, other countries where complaints about excessive delay have been prominent in the public discussion include Bangladesh,24b9735b3682 Botswana,acff01715f27 Croatia,e8b28f27ff2c and Kenya.b4ec592ea31a That said, some of the reasons an anti-corruption court might fail to meet its targets for timely case processing lie outside of the court’s direct control. A common culprit (or perhaps scapegoat) is the prosecutor’s office. In some cases, delays in case processing (and failure of the specialised courts to comply with their deadlines) have been attributed to overworked, understaffed, or inefficient prosecutor’s offices. Examples include Botswana,9eddf0b487e5 the Philippines,17a1f00862f9 and Nepal.b7d03c18b55b Some critics, however, have blamed the anti-corruption courts for being too indulgent with prosecutors who continually seek postponements – a criticism raised, for example, in Botswana85cef848c034 and the Philippines.7a122d721147

Taken together, experiences with specialised anti-corruption courts around the world suggest that although there may well be efficiency gains associated with the creation of such courts, reformers must be cautious. They should not be overly optimistic about, and should not overpromise, the extent of such gains. The degree to which efficiency gains will be realised in practice depends on many factors, including the resources devoted to the court, existing levels of judicial capacity, and several of the institutional design choices discussed further in Section 4.

3.2. Integrity

A second motivation for creating specialised anti-corruption courts is to ensure, to the extent feasible, that corruption cases are heard by an impartial and independent tribunal, free of both corruption and undue influence by politicians or other powerful actors. This rationale should be familiar, as it is one of the standard justifications for creating ACAs to investigate and/or prosecute corruption cases. While the integrity rationale has not featured as prominently as the efficiency rationale in public discussions regarding the creation of specialised anti-corruption courts, in a few instances the interest in ensuring judicial integrity was a central motivation for the creation of such courts.

Perhaps the best illustrations of this are Indonesia and Ukraine. In Indonesia, post-Suharto reformers established the so-called Tipikor courts primarily because of concerns about widespread corruption in the regular judiciary, which made it very difficult to secure corruption convictions of well-connected public officials and their cronies.9cf0d4833ea1 The designers of the Tipikor court system therefore enacted a number of specific measures to promote judicial integrity, including provisions requiring the participation of ‘ad hoc’ judges who are not part of the regular judiciary.1833218816b3 Similarly, civil society reformers in Ukraine after the Maidan Revolution distrusted the integrity of the regular courts, particularly in the context of corruption cases. They therefore pushed for the creation of a specialised anti-corruption court, with special candidate screening procedures that involve a panel of international experts, principally as a means of ensuring greater judicial integrity.9271bc2dac40

While Indonesia and Ukraine are the best-known examples of countries where the promotion of judicial integrity was a principal rationale for the creation of specialised anti-corruption courts, this factor seems to have been significant in some other cases as well. In Slovakia, one of the arguments for giving the Special Criminal Court (SCC) jurisdiction over serious corruption cases was the concern that local networks of elites (and criminal elements) could interfere with or otherwise distort judicial decision making in the regional courts. The SCC, as a national court located in the capital, was thought to be less susceptible to this problem.393851dc5f2e In Albania, by constitutional law, candidates for judges and judicial civil servants in the specialised courts, as well as their close family members, must successfully pass a review of their assets and background. They must also consent to periodic reviews of their financial accounts and personal telecommunications.d169a62f7e10

The degree to which specialised anti-corruption courts are more willing and able than ordinary courts to convict high-level or well-connected defendants, however, appears uneven. Some courts have been praised for their independence. An example is the Indonesian Tipikor courts, although subsequent developments – including the expansion of these courts to all Indonesian provinces, following a successful constitutional challenge to the courts’ original design – have raised concerns about an erosion of integrity in the Tipikor system.49e73721cc3b In many other countries, however, the anti-corruption courts have been criticised for having done too little to eliminate the culture of impunity. Such criticisms have been voiced in, among other places, Burundi,9a47b72bf659 Cameroon,30e9a1a181f0 and Nepal.2e0651ec7699 Moreover, although the usual worry raised with respect to political interference with the judiciary in corruption cases is that the courts will shield powerful wrongdoers from legal accountability, in some countries critics have alleged that the government is able to manipulate the anti-corruption courts, and anti-corruption prosecutions more generally, in order to harass political opponents. Such criticism are heard in, for example, Bulgaria,d78607270f8b Burundi,8926f325d99d Cameroon,67fef2f2a7fc and Tanzania.9addd0c8ab36

Of course, the creation of specialised anti-corruption courts is no guarantee that these courts will not themselves be corrupted. Even in Indonesia, where the role of the specialised courts as a bulwark against corruption has been most explicit, several judges on these courts have themselves been indicted for corruption.5bc54dbd8934 And in the Philippines, the Supreme Court dismissed a Sandiganbayan associate justice due to his alleged links to a massive corruption scheme involving the Philippine legislature.008e38a67f0b The Bulgarian Specialised Criminal Court was criticised for having been captured by political interests of the Borisov government and colluding with the powerful Specialised Prosecutor’s Office; both specialised institutions were abolished by a newly elected parliament in April 2022.bbfe7feced3e

3.3. Expertise

A third justification for creating a specialised anti-corruption court, closely related to but distinct from the interest in increasing efficiency, is the desire to create a tribunal with greater expertise. After all, many corruption cases, especially those involving complex financial transactions or elaborate schemes, are more complicated than the run-of-the-mill cases that make up many generalist judges’ criminal dockets. Indeed, the desire for a more expert adjudicative body – to promote not just efficiency but also accuracy – is a common justification for the creation of other types of specialised tribunals.464e34d0ec7e Perhaps surprisingly, though, the interest in fostering expertise has not been emphasised in most of the public discourse about the creation of specialised anti-corruption courts. True, this interest is sometimes invoked. For example, in Croatia, the creation of a specialised tribunal, to handle not only corruption cases but also other serious crimes, was in part an effort to build judicial capacity to handle the most complex and socially significant criminal cases, principally through the recruitment of more experienced judges to serve on these courts.1b2bafb7c4f9 But in most countries specialised expertise has been less prominent as a rationale for anti-corruption courts than for other sorts of specialised courts, such as those reviewed, for example, by Gramckow and Walsh.dd488a9d3c63

That said, the fact that corruption cases often call for special expertise has provoked some discussion of reforms to existing anti-corruption courts. First, and most straightforwardly, there have been increasing calls for, and some investment in, better training for judges on anti-corruption courts, particularly regarding financial matters, accounting, and anti-money laundering rules. The need for anti-corruption judges to receive more training in these and other technical issues has been raised, for example, in Bangladesh,e836f2c5448e Kenya (see Box 1), and Malaysia.442128e21e80 Second, some jurisdictions that do not currently provide for exclusive specialisation by their anti-corruption judges may reconsider that choice. In Malaysia, for example, the judges of the anti-corruption trial courts rotate between these courts and other courts; critics have argued that having generalist judges sit on a specialised court is in tension with the very notion of having specialised courts in the first place, and they have pressed for more specialisation.679a66ec29c9 And in Palestine, the 2012–2014 National Strategy on Anti-Corruption specifically called for judges of the Corruption Crimes Court to devote themselves exclusively to those cases so as to develop their expertise in the field.662b3b265b43 This was made mandatory by law in 2018.f490e9728f81

Table 2 summarises the main mechanisms and institutional design considerations that are currently used in anti-corruption courts to raise efficiency, integrity, and expertise. The institutional design considerations are extremely simplified here and are discussed in more depth in Section 4.

Table 2. Summary of motivations, mechanisms, and design considerations

|

Motivation |

Mechanisms |

Institutional design considerations |

|

Efficiency |

Favourable judge-to-case ratio Efficiency gains through expertise Streamlined procedures Deadlines |

Number of judges Scope of jurisdiction:

Specialisation only at some levels (first instance or appellate) or throughout, depending on where bottlenecks are found Relationship to prosecutorial authorities |

|

Integrity |

Insulation from existing court system, e.g., location of court; special selection and recruitment mechanisms Surveillance and asset declarations |

Number of judges and recruitment pool Geographic expansion (the larger and more decentralised the court network, the more difficult it is to oversee integrity, but there might also be benefits in some competition and possibility to refer cases to another geographic area) |

|

Expertise |

Selection of judges with special expertise and capacity to understand complex financial cases (regular rotation can be an obstacle unless there is a pool of such specialists) Targeted training |

Scope of jurisdiction Human resources Management: establishment and maintenance of an expert pool |

4. Institutional design choices

Although many countries have anti-corruption courts of some kind, there is a great deal of variation in the design of these institutions. Anyone considering the creation or reform of an anti-corruption court must pay attention to institutional design questions. There is no single ‘correct’ model or ‘best practice’ for the design of a specialised anti-corruption court; the appropriate design depends on many contextual factors and on the main objectives for the institution. In this section we discuss five of the most significant choices that institutional designers must make:

- The relationship of the special anti-corruption court to the regular judicial system

- The size of the anti-corruption court

- The procedures for appointing and removing special judges

- The substantive scope of the anti-corruption court’s jurisdiction

- The relationship to prosecutorial authorities

4.1. The relationship of the special anti-corruption court to the regular judicial system

Anti-corruption courts come in a variety of forms. Some are established as special branches or divisions of existing courts, while others are separate, stand-alone units within the judicial hierarchy. In still other cases, individual judges are given special authorisation to hear corruption cases, but there is no distinct anti-corruption structure, unit, or division. Across these categories, designated judges may work exclusively on corruption cases, or they may continue to preside over other cases as well. For example, in Bangladesh and Kenya, the trial court judges or magistrates designated as special judges/magistrates do not hear corruption cases exclusively; rather, they continue to serve as regular trial judges for ordinary criminal matters or other special cases.c1105979ffed And in Senegal, the Court for the Repression of Illicit Enrichment085bde279a8a is an ad hoc tribunal whose members are appointed from the pool of senior judges. These judges may continue to serve on their original courts even after appointment to the CREI.a525ed0a3f5a

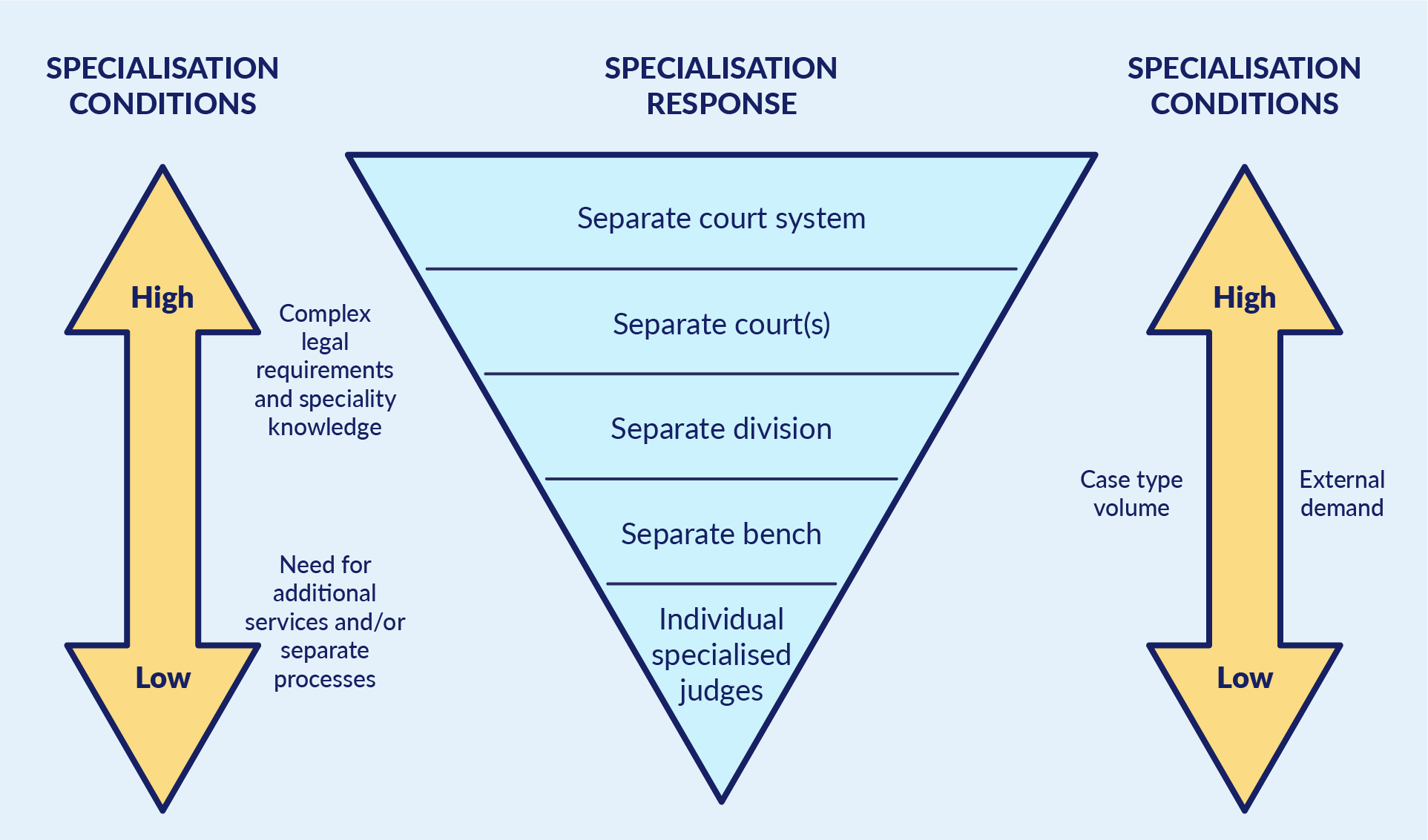

Different degrees of institutional separation and specialisation come with different costs and benefits. Gramckow and Walsh61d92fef561f have set forth some basic considerations (see Figure 2). Generally speaking, a greater degree of institutional separation will typically be more appropriate when the caseload is higher, when the need for efficiency is greater, and when the need for specialised expertise is more acute.7430a91a34c1 Another consideration that is particularly relevant with respect to corruption cases is the fact that defendants in such cases can often afford the best lawyers, who will use all available legal means to delay the legal process and challenge a guilty verdict. In countries like Uganda, where only the first instance courts are specialised for corruption cases, the general appellate courts can struggle with the high volume of appeals.4be14d812ead

Institutional separation also comes with costs. The more elaborate and extensive the specialised system is, the more expensive it is likely to be. Other potential negative effects of specialisation may include overly close relationships between specialised judges and other actors (lawyers, experts); loss of perspective and failure to see the bigger picture; and the risk of counterproductive status differentials between specialist judges and generalist judges.f44333e7dfe1

Figure 2. Gramckow and Walsh decision-making model for specialisation choice

Source: Adapted from Gramckow and Walsh 2013, p. 16.

While it is important to ask whether the anti-corruption court should be a separate body and whether the designated judges should specialise exclusively in anti-corruption cases, perhaps the most significant question with respect to the relationship between anti-corruption courts and the regular judicial system concerns the place of the special court in the judicial hierarchy. In particular, should the specialised anti-corruption court have original jurisdiction (that is, serve as a first instance trial court), or appellate jurisdiction, or some combination? And which court should have appellate jurisdiction over the anti-corruption court’s rulings? The countries that have created specialised anti-corruption tribunals have made quite different choices with regard to these questions.

Classifying the existing anti-corruption courts into categories that capture their relationship to the rest of the judicial hierarchy turns out to be difficult because of the great variety of systems. The place of the anti-corruption court in the judicial hierarchy (in terms of level or rank) does not always correspond to its function (first instance or appellate), and the systems for appeals vary considerably.

If we divide by function, four main categories can be distinguished. First, the most common approach is for a special anti-corruption court to serve as a first instance trial court. Examples in this category include Bangladesh,a268f2238144 Burundi,f2e7624c302634c44c9237c5 Cameroon,f8f20d548996 Nepal,f68d2e32c9ec Montenegro,6c5682c3e8e9 Pakistan,ad7253a65349 Senegal,7ac96862ec2d Sierra Leone,5fd420a4cc2b Slovakia,b1901df8b92c Sri Lanka,434e6db1f823 and Thailand.2e83241dadaf36c73f5d76d2 Appeals from there go through one or more of the usual intermediate layers of appeals or directly to the country’s supreme court.

Second, some countries have adopted a hybrid system in which the anti-corruption court can serve as a court of first instance in some cases (usually in more significant cases) and as an appellate court in other cases. The two notable examples in this category are the Philippines and Uganda. In the Philippines, the Sandiganbayan has exclusive original jurisdiction over corruption offences committed by sufficiently high-ranking public officials. When those offences are committed by lower-ranking officials, the regional trial courts have original jurisdiction and the Sandiganbayan has appellate jurisdiction.6ba50f868728 The Ugandan system is similar, in that the Anti-Corruption Division (ACD) of the High Court typically only serves as a court of first instance in high-value cases; in other cases, the ACD hears appeals from magistrate judges.

There are two important differences, however. First, in the Philippines, the Sandiganbayan’s original jurisdiction is limited by law; while in Uganda, the ACD has original jurisdiction in all corruption cases, but as a matter of discretion it chooses only to serve as a court of first instance in more significant cases. Second, in the Philippines, Sandiganbayan decisions can be appealed directly to the Supreme Court.3dbba81dcd16 In Uganda, on the other hand, ACD decisions are appealed first to the Court of Appeal (which in the Ugandan judicial hierarchy is between the High Court and the Supreme Court), and only then to the Supreme Court.be0d9fc9bc25 Tanzania emulated the Ugandan model in 2016 in that its Corruption and Economic Crimes Division at the High Court hears both appeals from lower courts as well as trials of cases of a certain magnitude. Unlike the Ugandan Anti-Corruption Division, it consists of only one judge and two lay judges who are appointed on a case by case basis but has no embedded magistrates. Its appeals go to the general Appeals Court.6d5c3c6fd7dc

In Botswana all corruption cases are heard initially by regular magistrate courts, but appeals are taken to the Corruption Court (a division of Botswana’s High Court), rather than to the ordinary appellate courts. Decisions of the Corruption Court can be appealed to the Court of Appeal, the highest court in Botswana’s judicial hierarchy, in the same way as any other High Court decision in Botswana.6f0b5dabb3e5 As the Botswana Corruption Court only has appellate functions and never functions as a court of first instance, it should be considered a separate, third category: a special appellate division.

Fourth, and increasingly common, are specialised anti-corruption court systems that include both courts of first instance and appellate courts. These comprehensive parallel systems comprise a set of anti-corruption trial courts as well as a set of anti-corruption appellate courts to hear appeals from the anti-corruption trial courts. Albania,a2a91bc7032c Armenia,60e2e3687f4b Malaysia,9aad7726ca7f Indonesia,cc1cd0b0629d Ukraine,28a478bbf4db and Zimbabwe1835011163f0 have created such systems.

Serbia constitutes a special case, with a comprehensive parallel system for large-scale corruption cases and first instance specialisation only for other corruption cases. Corruption cases involving high-level public officials and/or exceeding a certain monetary threshold are heard by the Organised Crime Court in Belgrade, with appeals going to the Organised Crime Department of the Appellate Court. Other corruption cases, however, are heard at the Corruption Departments that are part of the High Courts in Belgrade, Kragujevac, Niš, and Novi Sad.432644268fa2 Their appeals are heard by the general Appellate Court.

Table 3 classifies the anti-corruption courts we surveyed based on their relationship to the regular judicial system, distinguishing four broad categories.

Table 3. Models of anti-corruption courts

|

Model |

Countries |

|

Trial court Anti-corruption court has original jurisdiction over corruption cases. Appeals from there go through one or more of the usual intermediate layers of appeals or directly to the country’s supreme court. |

Bangladesh* |

|

Hybrid court Anti-corruption court may serve as a court of first instance for some (more important) corruption cases, and serves as an intermediate appellate court for other corruption cases that are heard in the first instance by generalist trial courts. |

Philippines |

|

Appellate court Anti-corruption court only hears appeals. |

Botswana |

|

Comprehensive parallel court with both trial and appeal function Anti-corruption court system includes both first instance trial courts and appellate courts. |

Albania |

* In Bangladesh and Kenya, lower-level courts’ judges are designated as anti-corruption judges/magistrates, while still hearing other cases at the general courts as well. Kenya added a specialised appeals layer in 2015.

** The current design of the Anti-Corruption Court in Burundi could not be established with certainty at the time of this update.

*** In Serbia the functional specialisation depends on the magnitude of corruption cases. A comprehensive parallel system is in place for large-scale corruption cases and those involving senior public officials, whereas for all other cases specialisation is limited to the first instance trial level.

4.2. Size of the court: How many judges?

A deceptively simple question that must be addressed when creating a special anti-corruption court is how large such a court should be. How many judges should sit on this court, or – if there is not a single body or division designated as a special anti-corruption court – how many special anti-corruption judges should there be? The answer to this question depends on answers to the questions posed in the previous subsection, in that the number of judges required depends in part on whether the specialised court is a court of first instance, an appellate court, or both. Even taking this factor into account, countries vary quite a bit in terms of the number of judges they designate as specialised anti-corruption judges.

The main advantage to appointing a large number of judges to the special anti-corruption court is straightforward: insofar as one of the objectives of such a court is to promote the speedy, efficient resolution of corruption cases, a higher judge-to-case ratio is desirable. This is especially true in countries that have a very large number of cases that could potentially come before the court, posing the risk of substantial backlogs. In the Philippines, for example, legislation attempted to address the persistent long delays in cases before the Sandiganbayan by increasing the number of judges from 15 to 21. Some critics contended that this increase was not nearly large enough, and that the number of Sandiganbayan judges ought to have been tripled to 45.e3c4df7b8722

There are, however, at least three potential costs to increasing the number of judges on a specialised anti-corruption court.

First, and most obviously, there is a concern about finding enough qualified judges. If the objective in creating a specialised court is not simply to improve the judge-to-case ratio for corruption cases but to ensure that highly qualified, experienced judges sit on these cases, it may be challenging to fill a significantly larger number of judicial positions, at least in countries with a limited judicial talent pool. This is especially true if the establishment of an anti-corruption court is accompanied by other judicial reforms that affect the operation of the judiciary, such as the lustration of judges.057c0f343999 Moreover, as the number of specialised anti-corruption judges increases, these positions may appear less ‘elite’ and thus less attractive to potential applicants.9b4b267ba9ce

A second concern about expanding the size of the specialised court is that recruiting highly qualified jurists to the specialised court may draw talent away from the regular courts, with an adverse impact on the rest of the judiciary. In many countries this will not be a significant problem, as the total number of well-qualified judges will be sufficiently large relative to the size of the special anti-corruption court. But in at least some circumstances, the judicial talent pool may be small enough that institutional designers will need to take seriously the question of how to allocate the most talented judges across courts.

A third problem is related but distinct: anti-corruption courts must be staffed only by judges of high integrity. For this reason, as discussed further below, some anti-corruption courts make use of special screening and selection procedures. But the more judges that need to be recruited for the special court, the harder it will be to rigorously apply those integrity criteria.

Worrisome developments in the Indonesian Tipikor courts since 2010 illustrate the concern. Under the original design of that system, each judicial panel comprised two career judges and three ad hoc judges, selected according to a careful screening procedure. These ad hoc judges had a strong reputation for integrity and impartiality. After a Constitutional Court ruling required the expansion of the Tipikor system, there was a need to significantly increase the number of judges, including ad hoc judges. Not only were there substantial difficulties in staffing all these new positions in 34 provincial capitals, but there were many more reports of malfeasance by the new judges, suggesting that the integrity screening and oversight were not as effective as previously.fe1e1c62162f

Since the initial recruitment round in 2010–2011, only a handful of new ad hoc judges have been appointed to the Tipikor courts. Concerns about their qualifications and integrity remain. Even though the law calls for the establishment of anti-corruption courts in all of Indonesia’s 347 districts, this has not happened as of 2022. Some observers have proposed recentralising the court in Jakarta, thereby reducing the number of required judges and easing the costs of oversight. Others recommend that the judges from the provincial-level courts travel and hear cases at district level, closer to the local prosecution and witnesses.4cc95dd4d5f7

In sum, when deciding how many judges to assign to a specialised anti-corruption court, institutional designers need to carefully evaluate the trade-off involved in increasing the number of judges, weighing the favourable impact on the judge-to-case ratio against the potential adverse impact on judicial capacity and integrity. In countries that have a very large number of corruption cases but are blessed with a good supply of qualified judges, a larger anti-corruption court may make sense; by contrast, when the number of cases that require the attention of a specialised tribunal is more limited, and the number of qualified judges is more limited as well, a smaller court is probably advisable. The hardest situations – unfortunately perhaps also the most common – involve settings where the number of corruption cases is large, but there are also significant limits on the available judicial talent pool.

4.3. Selection and removal of judges

In most countries, anti-corruption judges have the status of regular judges, and so the procedures for appointing, removing, and overseeing them, as well as their terms and conditions of service, are the same as those for other judges at a comparable level of the judicial hierarchy. However, a few countries have special rules for judges on the anti-corruption court, most notably with respect to appointments. For example, there are sometimes special appointment rules or qualifications requirements for anti-corruption judges. These often take the form of requirements that the judge have sufficient rank and/or experience before becoming eligible for appointment as an anti-corruption court judge. In some countries, notably Slovakia, judges are also required to pass a security clearance, designed to ensure that they do not have anything in their backgrounds that might make them susceptible to blackmail or other forms of improper influence. This requirement in Slovakia was initially limited to judges on the Special Criminal Court, but it has since been extended to all judges.327b1f8b49cf

The most far-reaching efforts to establish special rules for the selection of anti-corruption court judges have been in Indonesia and Ukraine. Judges who sit on the Tipikor courts in Indonesia include not only career judges but also so-called ad hoc judges (typically lawyers, law professors, retired judges, and other legal experts). Applicants for ad hoc judge positions must meet a strict set of selection criteria, with both civil society representatives and Supreme Court staff serving on the selection committee. Tipikor court judges are then appointed by the president for a term of five years, renewable one time only. Under the original 2002 legislation, the Tipikor courts decided cases in panels of five judges, three of whom had to be ad hoc judges; this system was designed to weaken the influence of the career judges, who were viewed as a greater corruption risk. However, pursuant to the 2009 revisions to the authorising legislation, enacted in the wake of the 2006 Constitutional Court ruling that invalidated the original Tipikor court system, the head of the Tipikor court in each judicial district (a career judge) can determine the combination of career and ad hoc judges on the panels.7417a3e4ebbe

The Ukrainian High Anti-Corruption Court is the only anti-corruption court so far that involves international experts in the judicial selection process. The High Qualification Commission of Judges manages the recruitment process of candidates for the whole of Ukraine’s judiciary. It is assisted by a Public Integrity Council (PIC) consisting of 20 members from civil society, academia, the media, and other professions, who participate in the screening of judicial candidates’ ethics and integrity. For the selection of HACC judges, the Commission is supported by a second council, the Public Council of International Experts (PCIE). It consists of six international experts proposed by international organisations to the Ukrainian government. The PCIE screens HACC candidates for integrity and ethics based on their asset declarations, memos from the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, and interviews. To proceed in the selection process, candidates must have at least three supporting votes from the PCIE and nine supporting votes from the PIC, or 12 votes in total. So if a candidate is opposed by four of the six PCIE members, he or she cannot progress in the process.b1c70bfef746

Ukrainian civil society groups pushed hard for the inclusion of foreign experts in the HACC selection process because of their deep distrust of the ordinary judicial selection processes and their belief that foreign involvement was essential for ensuring the appointment of honest and impartial judges to the HACC. These civil society groups succeeded in gaining the support of the Venice Commission and the International Monetary Fund, which made the involvement of international experts in the HACC selection a condition for release of further loans. While the High Qualification Commission of Judges reportedly came to appreciate the rigour of the PCIE during the first-ever selection round of HACC judges, 28 judges who were rejected by the PCIE in early 2019 on integrity grounds remained sitting on the bench of other courts.c3b33ce28030

Special selection and removal procedures for anti-corruption court judges are most sensible when concerns about judicial integrity are strongest. In Slovakia, the main perceived threat was from criminal networks that might be able to blackmail or corrupt judges. In Indonesia and Ukraine, the concern was the pervasive influence of powerful elites over the regular courts, as well as systematic corruption in the court system. Special judicial appointment procedures, however, may not be necessary to ensure integrity, and most other countries with special anti-corruption courts have not adopted special appointment and removal procedures. It is not always clear whether this is because policymakers in these countries have determined that special procedures are not necessary, or because of other political or practical considerations.

It is also important to keep in mind that special judicial appointment procedures are not sufficient to ensure integrity. They are, at most, one potentially helpful component of a larger strategy to protect judicial integrity, and they may or may not be worthwhile depending on the particular context. The case for special appointment procedures or criteria is strongest when the ordinary judiciary would be particularly susceptible to undue pressure or influence in corruption cases, which an alternative method of judicial selection might avoid.

4.4. Substantive scope of anti-corruption court jurisdiction: What cases does the court hear?

Anti-corruption courts vary in the scope of their substantive jurisdiction. Simplifying somewhat, there are three main dimensions along which a specialised anti-corruption court’s jurisdiction may vary (aside from the distinction between original and appellate jurisdiction, discussed previously). These are (a) the specific offences covered, (b) the magnitude of the offence (usually measured by the amount of money involved), and (c) the seniority of the government officials allegedly involved.

Type of offence: Most anti-corruption courts deal with a broad range of corruption and corruption-related crimes. Furthermore, some of the specialised courts that we have classified as anti-corruption courts in fact have broader jurisdiction that includes not only corruption and related economic crimes, but other serious crimes as well. This is particularly common in Southeastern Europe, where the specialised courts also hear organised crime and other cases (see Box 2). Similarly, Nepal’s Special Court has jurisdiction not only over corruption and money laundering, but also over ‘treason against the state’.a716c282cca9 Conversely, the jurisdiction of some other anti-corruption courts is more narrowly limited to a subset of specific corruption-related offences. For example, Senegal’s Court for Repression of Illicit Enrichment, as its name implies, only has jurisdiction over the crime of illicit enrichment – the use of public office or a relationship with the government to misappropriate public funds – and closely related corruption or concealment offences.fa7bab546c49

Box 2. Extended jurisdiction of anti-corruption courts in Southeastern Europe

by Ivan Gunjic

There are a number of specialised courts and court divisions in Southeastern Europe that have substantial jurisdiction not only over corruption cases but over other types of offences as well. This additional group of offences includes (a) organised crime (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovakia); (b) crimes against the state and the public order, most notably terrorism (Albania, Bulgaria, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia); (c) crimes related to international criminal law (Montenegro, North Macedonia); and (d) other serious crimes, such as human trafficking (North Macedonia) or premeditated murder (Slovakia). The added responsibilities range from organised crime cases exclusively (Croatia) to all the above-mentioned offences (North Macedonia).

The scope of jurisdiction of the courts in question does not necessarily reflect the proportion of corruption cases in their docket. While the Special Criminal Court in Slovakia is competent to adjudicate considerably more types of offences than the USKOK Courts in Croatia, their respective dockets include a similar share of corruption cases, between one-third and one-half (Stephenson 2016b; Attorney General Croatia 2021). Remarkably, two-thirds of the caseload of the Specialised Department for Organised Crime, Corruption, Terrorism and War Crimes of the High Court in Podgorica, Montenegro, consists of corruption offences, despite the broad remit evident in the department’s name (High Court Podgorica 2020).

There are several possible reasons for the extended jurisdiction of anti-corruption courts in Southeastern Europe. First, countries might aim to take advantage of benefits resulting from the pooling of different case types. Such benefits can arise from shared characteristics of the cases in question, such as similar challenges they pose for the judiciary or overlapping groups of participants. The close links between corruption and organised crime in the region (e.g., Holmes 2007) might help explain why these two types of offenses are consistently handled together. Furthermore, some anti-corruption courts in Southeastern Europe have incorporated competences of pre-existing court structures from which they emerged. The former Serious Crimes Courts in Albania, which were transformed into the SPAK Courts in 2019, had jurisdiction over certain corruption cases since 2014 (Gunjic 2022). The extended competences of anti-corruption courts in the region could also be the result of conditionality pressure from the European Union. For instance, the Audiencia Nacional of Spain, which holds jurisdiction over various types of serious crime, has been described as a possible blueprint for the Special Court in Slovakia and the now-abolished Specialised Criminal Court in Bulgaria (Kuzmova 2014). Croatia and Romania played a similar role for Albania (Gunjic 2022).

Magnitude of the offence: While the jurisdiction of most anti-corruption courts is defined by the nature of the offence rather than its magnitude, in some countries the specialised anti-corruption court only hears cases involving sufficiently large sums. In Cameroon, for instance, the Special Criminal Court only has jurisdiction over embezzlement cases involving especially large amounts; other embezzlement cases are heard by the ordinary courts.7378171ac506 The Philippines amended the law on the Sandiganbayan to restrict that court’s original jurisdiction to cases involving amounts of money that exceed a specified threshold.83d35d7937ed

Identity of the defendant: Some anti-corruption courts’ jurisdictions are limited not only to particular offences, but to particular offenders. The Sandiganbayan, for example, only has original jurisdiction over cases brought against sufficiently senior public officials.fbd715ede90b Interestingly, Burundi limits the jurisdiction of its Anti-Corruption Court in the opposite direction: although this court has broad jurisdiction over a range of corruption offences, only Burundi’s Supreme Court can rule on criminal charges brought against a range of high-level government officials, including ministers, deputies, senators, generals, provincial governors, and senior judges.63226d53d6d5

In Serbia the identity of the defendant and/or the monetary magnitude of the offense both determine which specialised court will hear the case. Corruption cases fall under the jurisdiction of the Organised Crime Departments when the receiver of the bribe is a senior elected or appointed official and/or when the illicit gain exceeds the amount of US$2 million or the value of the public procurement exceeds US$8 million. The Corruption Departments have jurisdiction over a comprehensive list of corruption cases (such as abuse of office, bribery, embezzlement, and money laundering), as long as they do not fall within the jurisdiction of the Organised Crime Departments.f6cf79be70ea

As emphasised above, there is no single right answer to the question of the appropriate substantive jurisdiction for an anti-corruption court. That said, it is possible to summarise some of the main advantages and drawbacks to imposing limits on the jurisdiction of such a court along one or more of the three dimensions noted above. The first advantage to imposing limits on an anti-corruption court’s jurisdiction is straightforward: as discussed earlier, a key determinant of a court’s efficiency is the judge-to-case ratio. While one way to improve that ratio is to increase the number of judges, another way is to decrease the number of cases, thereby enabling the court to focus its resources on those cases that are considered most important, or those for which adjudication by a specialised tribunal is otherwise most desirable. A second potential advantage to limiting the anti-corruption court’s jurisdiction is political. One purpose of such courts is to increase public confidence that the legal system is able to tackle corruption effectively, countering the perception of impunity for high-level officials and their cronies. Also, because the specialised court may require considerable public resources, and its judges may sometimes be perceived as having more favourable terms of employment than other judges, the sustainability of the court may depend on the public’s continuing belief that this body is necessary. Both of these perceptions can potentially be undermined if a large proportion of the court’s docket appears to consist of cases that seem relatively unimportant.

This line of criticism is not purely hypothetical. In Nepal, for example, critics have harped on the fact that a large number of cases heard by the Special Court involve forged certificates rather than major bribery cases, though this may be more the fault of the anti-corruption agency’s choices regarding which cases to prosecute.ccbc2e9131d5 Likewise, in Slovakia, critical media coverage has highlighted the fact that many of the cases resolved by the Special Criminal Court involve petty bribes, sometimes less than 20 euros. This has led some civil society activists to propose limiting the SCC’s jurisdiction to more important cases.52bb5547c3c3 And some critics complain that Zimbabwe’s fledgling anti-corruption courts have been inundated with petty cases.701cbf7823db

This is not to say, however, that limiting an anti-corruption court’s jurisdiction is a good idea in all (or even most) cases. After all, if the specialised court is indeed a better venue than the regular courts for adjudicating corruption cases, then giving the specialised court broader jurisdiction will mean that the specialised court’s distinct advantages (greater efficiency, expertise, integrity, etc.) will be brought to bear on a larger number of cases. Moreover, even ‘minor’ corruption cases may be important – either because they cumulatively have a large impact on the society, or because instances of seemingly low-level corruption can figure significantly in the workings of larger corrupt networks.

4.5. Relationship to prosecutorial authorities

Often, specialised anti-corruption courts are directly linked to specialised anti-corruption authorities or similar prosecutorial bodies, with the jurisdiction of the anti-corruption court limited to cases brought by the ACA. And sometimes the ACA has exclusive jurisdiction to file cases in the special anti-corruption court. For some anti-corruption courts, particularly those in countries influenced by the more inquisitorial French civil law tradition, special anti-corruption prosecutors and investigators are integrated into the institution of the anti-corruption court itself, with those prosecutors having exclusive jurisdiction to bring cases before the court – though they may also take cases referred by other entities. This is so, for example, in Burundi,4abe37410ae2 Cameroon,2b104f34f02b and Senegal.56773a2872f9

In contrast, some anti-corruption courts hear cases brought by the regular prosecutor’s office, either because the country does not have an ACA or because the ACA lacks the power to bring prosecutions directly. In Malaysia and Kenya, for instance, the public prosecutor (not the ACA) has the power to file cases in the anti-corruption courts.5c2a55cd7c62 And in some countries, the anti-corruption court may hear cases brought either by the ACA or by the regular prosecution service. In Uganda, for instance, the High Court’s Anti-Corruption Division hears cases brought both by the Director General of Public Prosecutions and bythe Inspector General of Government (Uganda’s ACA), as well as by Uganda’s Revenue Authority.ea47ae291ca4

Indonesia is a particularly interesting example to consider here, because the authority to bring cases before the Tipikor courts was altered by a ruling of the Indonesian Constitutional Court. Under the original 2002 law, only Indonesia’s ACA, known as the KPK, could bring cases before the Tipikor courts; equivalent cases brought by regular prosecutors were heard by the regular courts. In 2006 Indonesia’s Constitutional Court held that this two-track system violated the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law. The court’s logic was that two defendants charged with identical misconduct could be tried by different judicial institutions – with different compositions, procedures, and conviction rates – depending on whether the KPK or the regular prosecution service brought the case.f6c18a9c96f0 The 2009 revisions to the law remedied this problem by requiring all corruption offences to go to the Tipikor courts, whether they are brought by the KPK or the regular prosecution service.

One of the issues that reformers should keep in mind is that the effectiveness of a specialised anti-corruption court depends in large measure on the effectiveness of the body or bodies that have the power to file cases in that court. When that body is ineffective, the entire process is hobbled: in other words, the chain is only as strong as its weakest link. In several countries, specialised anti-corruption courts seem to do a good job handling the cases that come before them, but the most significant cases – the ones for which a specialised court is arguably the most important – do not reach the court at all, because the ACA or prosecutor’s office does not bring these cases. Indeed, corrupt elites may be content to allow a specialised anti-corruption court to operate without interference so long as they can exert enough influence over prosecutors or law enforcement to avoid any serious risk of prosecution. Several critics in Slovakia, for example, have asserted in the past that this is the main reason for the lack of any convictions of high-level politicians in Slovakia’s Special Criminal Courtac7ba7239be3 – something that was sadly confirmed by the unravelling of a corrupt network of police, prosecutors, and even a judge in 2020.6504dabeef1a Similarly, in Zimbabwe, the new anti-corruption courts have fallen short of expectations in part because of inadequate investigations and insufficiently prepared prosecutors.01fb0bfd4f17

There is some debate about the extent to which a specialised court itself can influence the behaviour of prosecutors. In the Philippines, many observers noted that the Office of the Ombudsman that investigates and prosecutes corruption cases was often responsible for the lengthy delays in cases heard by the Sandiganbayan, for example by not being adequately prepared on hearing dates and requesting frequent continuances. This has been addressed to some degree by new procedural rules issued by the Supreme Court in 2017 and 2018.36332e0ad7ed

The larger point here is that institutional designers need to think about the anti-corruption justice system as a whole and design the system so that the various parts work effectively in tandem. These component parts include the ACA (and/or regular prosecutors), special anti-corruption courts, law enforcement, and so on. Only when the context is well understood does it make sense to carefully consider a range of institutional design choices.