Query

Please provide a summary of the recent development of public-private partnerships (PPPs) between governments and industry in curbing illicit finance, including the evidence on their effectiveness.

Introduction

The last ten years has witnessed a proliferation of partnerships between private sector entities, such as banks, and public authorities, such as financial intelligence units (FIUs), with the stated aim of sharing information to prevent and detect forms of illicit finance. This Helpdesk Answer explores the rationale for and evolution of these partnerships, as well as the available evidence on their effectiveness. Lastly, it gives an overview of some of the challenges they face but also concerns associated with such partnerships as raised by commentators.

The answer purposefully adopts the term “public-private partnership for sharing financial information” (shorthanded here as FISPs).eae3e167c822 With this, the focus of the answer is limited to partnerships whose primary purpose is to enhance financial information sharing567774b789c2 between the public and private sectors. While there are also voluntary and regulatory initiatives whose goal is to improve information sharing between private entities, so-called private-to-private-partnerships (for example, between commercial banks), this falls beyond the scope of this answer.ee8a683e0b8b

FISPs may focus on addressing the financial dimension of one form of crime, but more commonly of multiple forms. Within the literature, the term “illicit finance” is often used and, while there is no consensus on a definition of this term, Benson (2024) notes it is largely considered to be broader than money laundering and captures a wider range of criminal activities such as corruption, terrorism financing and proliferation financing, among others. There are two main overarching links between illicit finance and corruption:

- the proceeds of a variety of corruption offences may be laundered through financial accounts and other vehicles (FATF 2011: 16)

- corruption may facilitate illicit finance practices, such as bribery in exchange for more lax oversight of the financial sector (Transparency International 2019)

The work of FISPs therefore may contribute to addressing corruption, even if most of the literature on such partnerships does not spell this out explicitly and instead refers to illicit finance more widely.

Rationale

According to Artingstall and Maxwell (2017: ix), FISPs have largely emerged as a response to perceived limitations in the existing anti-money laundering (AML) regulatory framework, which is largely based on recommendations by the global Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Artingstall and Maxwell (2017: 3-4) describe how the FATF framework essentially assigns specific roles to private and public actors:

- AML obligations require private sector entities across various sectors70b8d483557c to use customer due diligence (CDD) or enhanced due diligence (EDD) as well as transaction monitoring procedures to identify and monitor client relationships that present a money laundering risk, and are obliged to file suspicious transaction reports (STRs) to the appropriate authorities.

- A financial intelligence unit (FIU) is mandated to receive and analyse STRs and pass on the pertinent results of this analysis to law enforcement authorities. They typically also have the statutory powers to request information from private sector entities.

- The law enforcement authorities then decide how to use the information passed on by the FIU; for example, to open a formal investigation of possible money laundering or predicate offences, or whether to use the intelligence for ongoing investigations.

- Oversight of the AML regulatory regime is conducted by one or more designated supervisory bodies, such as banking supervisors, dedicated AML supervisory agencies or professional bodies entrusted with AML supervisory responsibilities.

However, information sharing under the FATF framework has encountered reported operational challenges when implemented at the national level (Maxwell 2020: 11). For example, Artingstall and Maxwell (2017: 10) find that private sector entities can find it difficult to fulfil their AML obligations in the absence of adequate guidance from public agencies on patterns or trends in criminal activity as well as specific information about individuals or entities under investigation or being monitored. Furthermore, while it is an obligation in many jurisdictions for FIUs to provide feedback to these entities on the reports they submit, legal provisions often do not specify how or when this information should be conveyed to reporting entities.e7ba9f2436e3

There have also been concerns raised regarding the quality and relevance of information shared by private sector entities and, with that, its usefulness for law enforcement responses to money laundering. Artingstall and Maxwell (2017: vi) conducted interviews with heads of various FIUs and found that, while there had been a rapid growth in the number of STRs filed in most jurisdictions, an estimated 80% to 90% of suspicious reporting was of no immediate value to active law enforcement investigations. The study also highlights how this is linked to the underresourcing FIUs typically experience: “given the resources that are typically available to them, the sheer number of reports can overwhelm the FIUs that are tasked with understanding their relevance in a timely manner” (Artingstall and Maxwell 2017: 5). They also interviewed private sector financial crime control leaders, 85% to 95% of whom either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that the framework for reporting suspicious transaction reports is leading to the effective discovery and disruption of crime (Artingstall and Maxwell 2017: vi).

In a similar vein, Vogel (2022:53) concludes that if an FIU is confronted with high volumes of low-quality STRs, it is likely that private sector entities are reporting out of “formal compliance” rather than reflecting on the quality of information; he also notes this may be attributed to the lack of guidance and feedback they receive from FIUs on what kind of information is actionable.

Against this background and the perceived limitations of the current system, according to Marsh (2024: 2), “[t]he aim of establishing a public-private partnership or platform for financial intelligence sharing is to vastly increase the flow of targeted, useful information back and forth between law enforcement and financial institutions”. Similarly, Vogel (2022:53) concludes that FISPs are largely a response to the need to align the reporting of private sector entities with law enforcement priorities through more purposeful information sharing. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that FISPs are not intended to replace the standard reporting obligations private sector actors face under the AML framework as outlined by the international standard set out by the FATF (“FATF framework”), but rather to complement it.833ae855fe74

A study commissioned by the EFIPPP (2025a: 7-8) explains that while cooperation between public and private actors is already facilitated under the existing FATF framework and standard reporting obligations, certain characteristics of FISPs enhance them. Namely, FISPs offer more institutionalised forms of cooperation which can facilitate more targeted and direct lines of communication, which enable, for example, private sector actors to obtain more direct feedback from FIUs on what kind of information is useful for investigatory and prevention purposes (EFIPPP 2025a: 7-8).

Key characteristics

As the European Commission (2022:2) notes, “there is no commonly agreed definition of what constitutes a public-private partnership in the framework of preventing and fighting [money laundering/terrorist financing]”, but they are “generally understood to imply the setup of a specific framework for sharing information between FIUs, law enforcement authorities and the private sector” beyond existing obligatory information sharing based on suspicious transaction reporting.

Aidoo (2025: 10) describes how, despite a diversity in models, FISPs normally do share some core characteristics. These include the fact that participation by private sector actors is voluntary, cooperation is grounded by trust and confidentiality agreements between the partners, and there is a focus on mutual learning and coordination.

Beyond this, FISPs can display significant variation in operating model, nature of information shared, thematic focus and participants. The remainder of this section gives a brief overview of some of these key characteristics of FISPs.

Governance and operational model

In terms of their governance, FISPs tend to be coordinated by national bodies to whom the partnership remains accountable in terms of outcomes and performance (Maxwell 2020). While FIUs often coordinate and even participate in FISPs, this is not always the case and another national body, such as a police agency, may instead play this role (Maxwell 2020: 15).

In terms of how FISPs structure their day-to-day operations, Maxwell (2020: 14) outlines three models:

- Co-location model: seconded public and private sector analysts work together in a dedicated office space in real time to share information and fulfil other objectives.

- Regularly convened meetings: public and private sector representatives – normally senior officials rather than analysts – convene on a regular basis to share information, which is then relayed back to their operational staff.

- Convened meetings with non-permanent membership, at the direction of the FIU: the FIU decides when to convene meetings, often on an ad hoc basis and the members invited to attend will often depend on the exact topic or case at hand.

As of 2020, most existing FISPs adopted either the second or third models and co-location remains a model employed by few (Maxwell 2020: 14).

Nature of information shared

In the context of financial investigations, information is often distinguished as being strategic or tactical in nature (European Commission 2022: 2-3; Maxwell 2020: 13):

Strategic information: aggregated information related to money laundering that serves to improve the compliance function of obliged entities. This can include, for example, typologies, trends, risk indicators, alerts or other information designed to improve the quality of STRs. These knowledge products do not contain confidential information and typically do not require a specific legal basis to be shared.

Tactical information: personal data or information which may be relevant to criminal law investigations. For example, the names of persons of interest or entities might be shared by law enforcement actors with private sector entities who can use this information to monitor their financial activities or disclose assets held by suspects. The legal basis for, and constraints on, this kind of information exchange depends on the national context.

While most FISPs share strategic information, many do not share tactical information or, if they do, only to a limited extente9199c9ea476 (EFIPPP 2025b: 5; Maxwell 2020: 13). This normally depends on whether or not national frameworks allow for so-called legal gateways, which enable tactical information to be shared in a way that does not violate data protection regulations (Maxwell 2019: 6; Bociga et al. 2024: 824). Furthermore, the legal requirements for doing so may be different depending on whether it is law enforcement or private actors doing the sharing (EFIPPP 2025a: 17).

The nature of the information shared is strongly correlated with the kind of cooperation a FISP aims to achieve. A study commissioned by the EFIPPP (2025a: 7-8) describes FISPs that may engage in one or more of the following three types of cooperation:

- cooperation to identify new investigative leads to trigger or guide investigations

- cooperation to support the gathering of evidence in support of ongoing investigations

- cooperation to disrupt a specific threat through preventive measures

Thematic focus

The defined thematic focus of FISPs can vary; some may encompass all sectors with AML reporting obligations, while others are more sector-specific and limit participation (Artingstall and Maxwell 2017; European Commission 2022: 5). The thematic focus of the FISP often has a bearing on which participants are invited to take part (EFIPPP 2025a: 20). For example, in the UK, while financial institutions are among the leading private sector participants involved in the JMLIT, there may be other dedicated FISPs in place for DNFBPs such as the Legal and Accountancy Intelligence Sharing Expert Working Groups (ISEWG) (Bociga et al. 2024: 822).

Further, other FISPs might be defined instead by the fact that they focus on the financial dimension of only one crime (for example, human trafficking) (MROS 2023: 6; EFIPPP 2025a: 20). In other cases, FISPs will be mandated to focus on illicit finance more broadly but will, within their structure, operate dedicated working groups on specific crimes.

Participation

In terms of which actors participate in FISPs, FIUs and relevant law enforcement actors (for example, representatives of economic crime investigatory bodies or branches) are normally present. However, given that FISPs are voluntary in nature, private sector entities are not per se required to participate.

Keatinge (2017) notes that larger financial institutions are, more often than not, the main participants because they are more likely to have sufficient resources to allocate to this purpose. Maxwell (2019: 6) also found that, as of 2019, FISPs generally comprised only a small numbers of regulated private sector entities relative to the total number of entities subject to AML obligations.

While participation is voluntary, this does not typically mean that every private sector entity wishing to participate necessarily can, and there are often vetting processes for being admitted. In a study on JMLIT (Bociga 2024), an FISP from the UK, an interviewed representative from the fintech sector expressed their view that many companies were not able to participate because they “were considered too small”.

Evolution and cases

Evolution

The evolution of FISPs is normally traced back to the establishment of the UK’s Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT) in 2015 (see overview below). Maxwell (2020: 12) describes how the JMLIT was regarded as a unique innovation,a8ed43e7fcc6 and that in subsequent years there was greater political momentum for FISPs which by 2020 had become a “mainstream component of the architecture to tackle financial crime in liberal democracies”.

For example, at the 2016 London Anti-Corruption Summit, 21 national governments committed to establish FISPs (UNCAC Coalition 2016).1b66f66ff94c They were also endorsed at the 2017 FATF plenary in Buenos Aires (Keatinge 2017) as well as subsequently by the United Nations Security Council and EU Commission and Parliament (Vogel and Lassalle 2023: v).

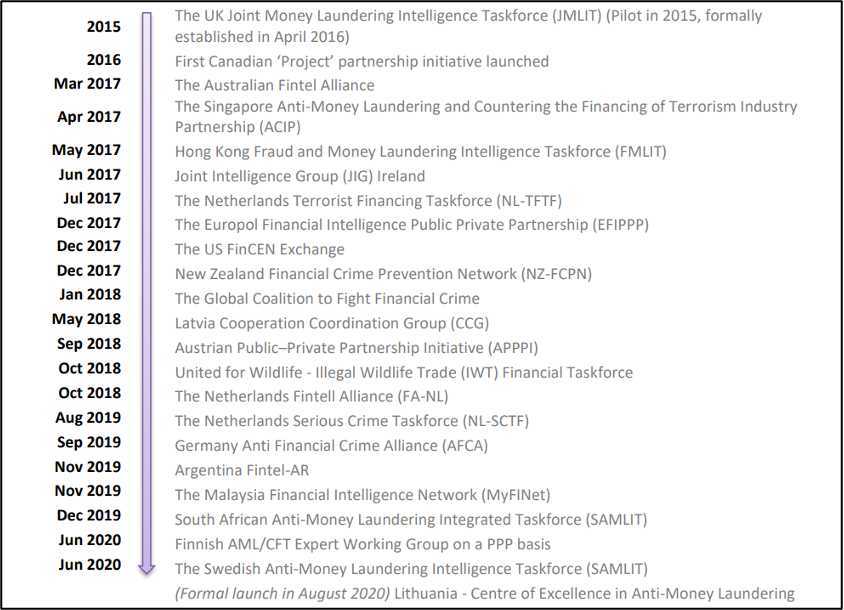

Maxwell (2020) identified 22 FISPs being established between 2015 and 2020 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Timeline of partnership development between 2015 and 2020

Source: Maxwell 2020: 12

This desk review did not locate any source providing an updated timeline or list from the period 2020 to 2025, making it difficult to comprehensively estimate the number of FISPs at the time of writing. Nevertheless, while the growth rate appears to have somewhat abated, FISPs do continue to emerge. For example, the Swiss Financial Intelligence Public Private Partnership (Swiss FIPPP) was established in 2024; in the same year, the Nigerian financial intelligence unit announced it was developing such a partnership (Nduka Chiejina 2024).

Cases

The remainder of this section provides a brief overview of five FISPs,6ae0074d5cc3 with a focus on their key characteristics as described in the previous section. It is possible to observe significant overlaps between different FISPs – which may take inspiration from each other – and degrees of variation. However, these examples also speak to the fact that the model and mandate of FISPs rarely remain static but rather evolve over time.

Additionally, an overview of existing evidence of their effectiveness is included. Given the rationale for FISPs, efforts to measure their impact or effectiveness normally assess whether the quality and quantity of information shared marks an improvement compared to standard reporting and, for example, enhances law enforcement responses to illicit finance.

However, it should be noted that such measurement efforts are inherently complex for a number of reasons. One is that many FISPs have been established only recently, making it difficult to conclusively measure impact (Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland 2023: 6).

Furthermore, it can be especially difficult to measure the impact of strategic information as opposed to tactical, given the former is primarily concerned with guidance of a preventive nature (Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland 2023: 6).

Finally, some FISPs – especially those which have more resources and/or have been operating for longer periods of time – that engage in the sharing of tactical information have reported statistics and case studies, which claim outcomes, such as an increase in the quantity and/or relevance of STRs produced, as well as investigations or prosecutions which have resulted from such information (Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland 2023: 6). However, most of the sources cited do not detail the methodology by which they have attributed the outcomes claimed to the information shared under the FISP.

Indeed, most existing assessments are internally conducted, often by representatives of the FISP themselves; the desk review for this Helpdesk Answer did not locate any comprehensive, independent efforts to measure the effectiveness of FISPs.

UK Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT/JMLIT+)

JMLIT (or since 2021 JMLIT+) is a FISP in the UK that facilitates tactical and strategic information sharing towards the prevention and detection of money laundering and other forms of economic crime (EFIPPP 2025). It has more than 200 members, including law enforcement, regulators, public sector bodies, financial institutions, insurance and investment companies, telecommunications firms, technology and social media companies, virtual asset service providers, accountancy and legal firms, the gambling industry and NGOs (NECC n.d.).

It was first piloted in 2015, and then in 2018 was incorporated into the multi-agency National Economic Crime Centre (NECC), which is housed in the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA).

JMLIT+ members may participate in so-called public-private threat groups and ad hoc focused working groups (known as cells) to detect current or emerging threats and to identify opportunities for collaboration.7dd9205e4d2f Meetings normally take place on a quarterly or monthly basis (EFIPPP 2025b: 8). These groups develop and share a combination of strategic information such as threat assessments, typology alerts and sector-specific guidance, as well as tactical information, for example, related to accounts suspected of being linked to money laundering activities (Bociga et al. 2024: 821-822). A more recent development is the data fusion capability that enables the sharing of bulk data in targeted datasets from the banking sector to the NCA, which can be used to identify persons of interest to be as well as develop guidelines (NECC n.d.).

JMLIT has a management team that acts as a single point of contact for all JMLIT+ groups and coordinates between the NECC and the groups, ensuring that all stakeholders are briefed on progress and opportunities for collaboration (NECC n.d.).

In terms of quantitative indicators on effectiveness, the UK NECC (2025) has reported that the JMLIT+ has been responsible for the following outcomes between its initial establishment in 2015 and the end of 2024:

- more than 10,700 accounts have been identified that were not previously known to law enforcement

- over 8,100 accounts have been closed

- more than 391 arrests

- more than 1,230 legislative orders granted in part due to JMLIT+ activity

- over UK£248 million in assets identified and frozen

Furthermore, while it did not attempt to quantify the impact, the NECC has reported that over this period 90 JMLIT alert products, such as typologies of emerging criminal trends, were disseminated. The NECC claimed these have not only been used by private sector entities to improve their compliance but have also led directly to targeted law enforcement actions (EFIPPP 2025b: 22).

Lastly, the NECC also reports exemplary law enforcement cases in which JMLIT information played role. For example, in 2022, the JMLIT operations group supported the police branch of the Ministry of Defence police by identifying 45 previously unknown accounts associated with a corporate entity that was suspected of fraud and money laundering in relation to a publicly issued defence contract (EFIPPP 2025b: 23); this ultimately resulted in the freezing of UK£53 million (EFIPPP 2025b: 23).

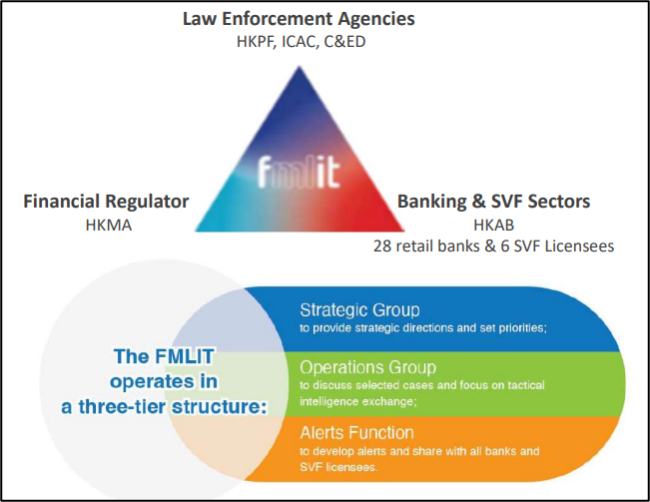

Hong Kong Fraud and Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (FMLIT)

FMLIT is a FISP from Hong Kong which enables the sharing of strategic and tactical information. Maxwell (2020: 56) highlights that while FMLIT addresses a wide range of money laundering risks, countering fraud is treated as a priority. It was established as a pilot in 2017 and became permanent in 2019 (Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau 2022: ix).

It brings together financial institutions, the central bank (Hong Kong Monetary Authority), as well as specialised law enforcement bodies such as the commission against corruption and customs (Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau 2022: ix). Maxwell (2019: 16 ) notes that because the legal gateway used by FMLIT to share information does not derive from domestic AML law, the Hong Kong FIU is – somewhat uniquely – not a leading agency within the partnership. As of 2023, 28 retail banks participated in FMLIT; the taskforce states it is adopting a phased approach on expanding its membership (Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau 2022: 33).

Strategic information is distributed through an alerts function, which regularly publishes guidance on typologies, trends and new topical issues, such as “money mule” risks (Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau 2022: 21). Tactical information is exchanged between financial analysts from the banks and law enforcement investigators in regularly held, confidential operations group meetings.

Figure 2: Membership and organisational structure of FMLIT

Source: HKBA 2024

Over 2023, it was reported that FMLIT identified 6,400 new suspicious accounts and contributed to the freezing or confiscation of around US$51 million in criminal proceeds (HKCGI 2024). Further, Zeng (2025) reports that the number of STRs filed on the basis of FMLIT intelligence reportedly quadrupled year on year in 2024, and the volume of criminal proceeds which had been confiscated increased by 34%.

FMLIT also provides details about individual cases. For example, in 2022 it initiated a pilot project to target money mules who set up bank accounts across different local retail banks to receive and launder crime proceeds of telephone and other fraud. This resulted in the identification of 400 suspicious bank accounts previously unknown to law enforcement (Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau 2022: 22).

Fintel Alliance (Australia)

In Australia, the Fintel Alliance enables the exchange of strategic and tactical information as part of the measures against money laundering, terrorism financing and other serious crime (Austrac 2025).

It is organised by the national FIU known as the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC), which includes hosting an office for the operations hub (see below). The alliance has over 30 members, including major banks, remittance service providers and gambling operators, as well as law enforcement and government agencies (Maxwell 2020: 52). The alliance was established in 2017.

In terms of strategic intelligence, the alliance publishes a series of financial crime guides to help understand, identify and report suspicious financial activity to detect and prevent criminal activities (Austrac 2025). In terms of tactical intelligence, the alliance partners work and collaborate both in person and virtually through two main mechanisms:

The operations hub, in which analysts seconded by public and private sector actors exchange and analyse financial intelligence “in close to real time”. This is achieved through co-location, where the analysts share a dedicated office space (Austrac 2025). As noted by Anderson et al. (2021), such co-location allows for more agile collaboration among partners on time-sensitive cases. Private sector analysts are vetted and cleared to access classified intelligence and there are restrictions in place on what information they can share with their seconding institution.

The collaborative analytics hub, which is essentially a common platform for data sharing and advanced analytics across public and private partners, aiming to provide intelligence to law enforcement that can facilitate investigations. In 2025 Austrac announced it would expand the operations of the hub, citing its success in producing actionable intelligence for law enforcement (Austrac 2025).

In terms of quantitative indicators, the Fintel Alliance regularly reports results in its annual reports. For example, in 2019 it reported having (Fintel Alliance 2019: 2):

- completed 320 investigations with the support of private sector members

- contributed to the arrest of 108 persons of interest

- contributed to the closure of accounts related to 90 high-risk customers

- identified or protected potential 87 victims of fraud

The same report also provides more detail on case examples. For example, it reports intelligence received from the alliance helped law enforcement to identify and disrupt a US$850 million fraud scheme that involved participants inventing fake businesses to claim false refunds (Fintel Alliance 2022: 23).

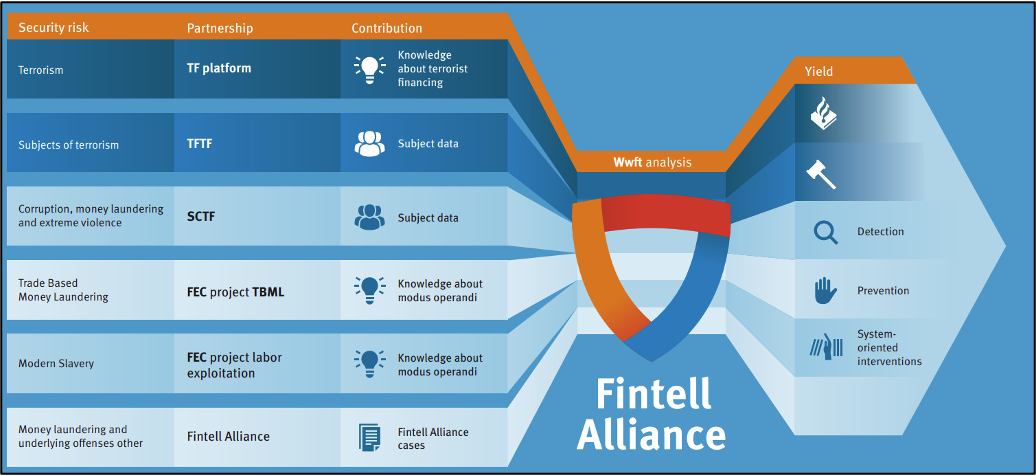

Fintell Alliance & Serious Crime Taskforce (Netherlands)

In the Netherlands, the Fintell Alliance is a FISP sharing strategic and tactical information to counter money laundering and terrorist financing (EFIPPPa 2025). Kosta et al. (2024: 27) describe how the alliance was designed to be mutually beneficial, supporting banks to fine-tune their monitoring and compliance systems while at the same time providing the FIU with more useful “unusual transaction reports”.6f300f734887 It is a partnership between the Dutch FIU and four major banks (Kosta et al. 2024: 27). It was established in 2018 initially as a pilot (Kosta et al. 2024: 27).

Bank employees are seconded to participate in the alliance but are subject to a screening process by the FIU (Kosta et al. 2024: 28-29). Members are not permitted to divulge any information shared beyond the alliance, and a secure data room is used for all Fintell Alliance meetings (Kosta et al. 2024: 28-29).

Employees from the FIU and the participating banks under the Fintell Alliance work at one physical location (Fintell Alliance NL 2023) and interact daily (EFIPPP 2025b: 8). In the event intelligence shared may be actioned for an investigation, the public prosecutor’s office may also be invited (Kosta et al. 2024: 28-29). An evaluation of the alliance undertaken by KPMG (2023: 130) concluded this model ensured shorter lines of communication and fostered effective collaboration.

The alliance forms part of a wider framework made up of other PPPs, including the Serious Crime Taskforce (SCTF) and various projects to address other crimes (see Figure 3) (Fintell Alliance NL 2023). The alliance holds regular meetings with these taskforces for coordination purposes (Kosta et al. 2024: 29).

Figure 3: Infographic detailing Fintell Alliance’s work

Source: Fintell Alliance NL 2023

The SCTF focuses on corruption, money laundering and extreme violence, and also enables strategic and tactical information sharing (Kosta et al. 2024: 23). Its members also include the five major banks and the domestic FIU, plus the national police, public prosecution service and the fiscal information and investigation service (Kosta et al. 2024: 21-22); Kosta et al. (2024: 27-28) distinguish the SCTF from the Fintell Alliance by stating that law enforcement agencies play a more leading role in the former (for example, in using information in investigations against corruption or organised crime). The SCTF started as a pilot in 2019 and become permanent in 2021 (Kosta et al. 2024: 21-22).

Both the Fintell Alliance and the SCTF have reported examples pointing to their effectiveness. In its mutual evaluation report of the Netherlands, the FATF (2022: 59) highlighted a case in which the members of the Fintell Alliance conducted a joint analysis of information shared, and uncovered an underground banking network involving more than 200 bank accounts and 600 companies with suspicious transaction activity estimated at €200 million. Due to its complexity, the report mentions it would have been unlikely that individual reporting institutions could have identified the scheme by themselves (FATF 2022: 59). In 2023, the SCTF claimed its work over 2023 led directly to 600 new suspicious transaction reports being issued to law enforcement involving activity worth an estimated €77 million (EFIPPP 2025a: 10).

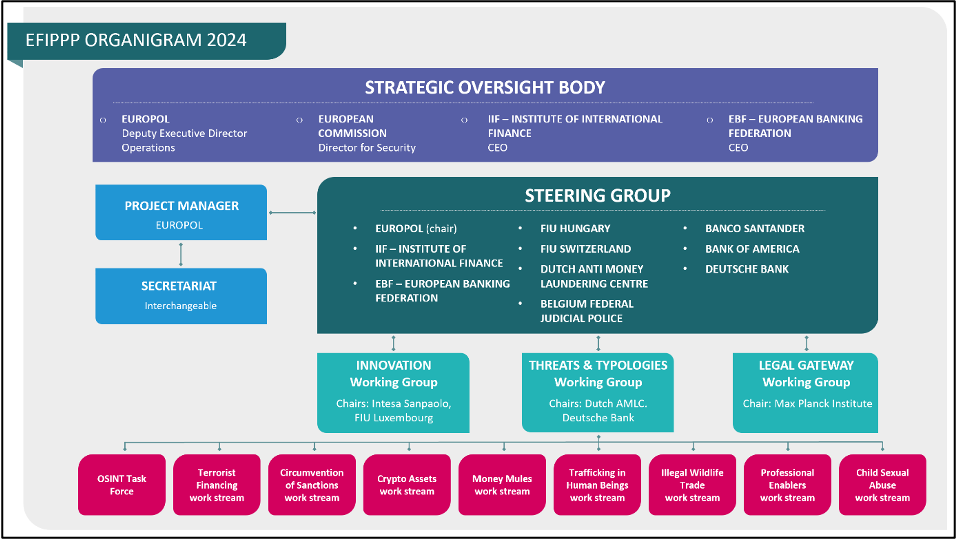

Europol Financial Intelligence Public Private Partnership (EFIPPP)

The EFIPPP (n.d.). describes itself as the first PPP for transnational information sharing in the field of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing. Its stated objective is to share both strategic and tactical information.

As of 2025, EFIPPP states it currently had “around 100 member institutions and observers from across the EU and some third countries” (EFIPPP 2025a: 4). Only law enforcement agencies, FIUs and financial institutions are full members, while other bodies – such as banking associations and international institutions – have observer status. It was first established in 2017 with a total of 28 institutions from 8 countries participating.

The EFIPPP Secretariat is located in the European Financial and Economic Crime Centre (EFECC) at Europol, and governance is supported by a strategic oversight body and steering group (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Organigram of EFIPPP as of 2024

Source: EFIPPP 2025

Despite its stated objective, EFIPPP appears to face limitations in sharing tactical information. This is perhaps not surprising; in a mapping exercise commissioned by EFIPPP, it was found that most EU member states do not have national level FISPs exchanging tactical information (EFIPPP 2025b: 5).3bdc2cdbffee Nevertheless, EFIPPP reportedly aims to promote the exchange of tactical information between jurisdictions that do have a domestic legal gateway for information sharing (RUSI 2019: 24), although this Helpdesk Answer could not identify case studies or other publicly available information on the frequency to which this is done in practice.

The strategic information shared by EFIPPP is largely achieved through three working groups, dedicated to innovation, threats and typologies, and legal gateways. The threats and typologies working group – which is broken down into a further nine work streams – has developed typologies based on recent investigations carried out by Europol and competent authorities to improve the detection of suspicious transactions. These typologies comprise detailed risk indicators, including specific geographical indicators, but do not contain personal data (Maxwell 2020: 80). The legal gateways working group has conducted a mapping exercise to better understand legal avenues to share information within a financial institutions, between EU member states and countries with equivalent personal data protection rules, as well as with countries with non-equivalent personal data protection rules (Maxwell 2020: 81).

This Helpdesk Answer was unable to locate reports giving quantitative or qualitative examples of EFIPP’s effectiveness. However, one noted impact of EFIPPP is that it has supported member states in the development of their own FISPs, such as the Germany Anti-Financial Crime Alliance (RUSI 2019: 24).

The EFIPPP has made efforts to assess the impact of FISPs more generally, undertaking a survey to which representatives of seven FISPs responded (EFIPPP 2025b). Respondents were asked to give their assessment on how often different “scenarios” produce value to criminal investigative outcomes (see Figure 5). While the EFIPPP (2025b: 8) acknowledges these responses are subjective and are not necessarily comparable, the results suggest a largely shared perception that certain FISP activities do regularly support criminal investigative outcomes, such as where information shared is used to improve the completeness and precision of compulsory information requests.

Limitations and concerns

Various commentators have highlighted that despite the proliferation of FISPs in the past decade, several limitations persist which restrict their potential. However, others note what might be better characterised as concerns about FISPs, highlighting certain risks they can pose. This section provides an overview of some of the key points of debate.

Information sharing bottlenecks

Some commentators argue that the emergence of FISPs have not fully resolved the information sharing issues the AML system experiences and that bottlenecks persist in various respects.

In most countries, regulated private sector entities are prohibited from sharing tactical intelligence with one another (Maxwell 2025). This creates inefficiencies given that most money laundering schemes involve the use of multiple accounts in multiple institutions (Anderson et al. 2021) and even if suspicious activity is detected in one account, the client may circumvent this by establishing a new account with another financial institution (Artingstall and Maxwell 2017: ix).

In most cases, the establishment of FISPs does not legally override this prohibition on sharing between private sector entities. This not only means the gap is unaddressed but it can create significant communication bottlenecks between the various partners participating in the FISP. However, Maxwell (2025) describes how some countries in recent years have passed legislation to enable “private-to-private (P2P) collaboration”. In this vein, Aidoo (2025: 7) gives the example of the UK’s Criminal Finances Act 2017 which introduced a mechanism by which multiple financial institutions can submit joint disclosure reports to the FIU to report on suspicious activities they have detected in their business operations.

Anderson et al. (2021) highlight that FISPs are still largely national in focus, which means they are not usually able to share information with public or private actors from other jurisdictions. Moreover, the FISP confidentiality agreements that enable STRs to be shared in one jurisdiction often exclude their circulation to affiliates or subsidiaries of the same financial institution in other jurisdictions (Anderson et al. 2021). While the EFIPPP marks something of an exception, as noted above, this Helpdesk Answer was unable to ascertain to what extent it has been able to facilitate the exchange of tactical intelligence between countries.

Finally, information sharing may be impeded by technological limitations. Writing in 2017, Artingstall and Maxwell (2017: 3) noted of FISPs that “their ability to disrupt underlying crime is restricted, in particular, by the lack of a technological basis to process a large volume of cases through the partnership model”. However, Aidoo (2025) argues that recent technological innovations and tools such as machine learning and secure information-sharing platforms can potentially be embraced by FISPs to process more data at a faster rate and produce stronger analysis, and ensure the information shared is protected.

Resourcing

As discussed above, FISPs need investment, and their full potential can be limited if resourcing is insufficient and/or unpredictable. A survey of FISPs from across Europe, found that “the size and resourcing of partnership activity varies quite significantly from partnership to partnership” (EFIPPP 2025b). For example, the UK’s JMLIT+ has a predictable budget and is staffed by a number of full-time officers from the NECC and NCA; in contrast, in the Netherlands, the Fintell Alliance has no dedicated public funding; instead, the public bodies participating must resource their engagement out of existing budgets (EFIPPP 2025b: 17).

This has implications for the model FISPs adopt and the impact they can achieve. Maxwell (2019: 7) finds insufficient resources for partnerships will diminish their ability to “invest in technology, to expand the operational bandwidth and to develop co-location arrangements”. Elsewhere, Maxwell (2020: 24) has argued that with exceptions such as Australia and the UK, most FISPs still tend to operate on a small scale.

As well as the public agencies, resourcing considerations also affect private partners. Given the reliance on voluntary participation, Aidoo (2025: 14) explains that FISPs require significant investment from banks, especially in models which use regular meetings and seconded staff for co-location purposes. The contributions financial institutions make to FISPs often come in addition to their standard AML compliance obligations, and Aidoo (2025: 14) notes “[s]ome banks worry that devoting resources to PPP topics might leave other areas under-monitored, potentially triggering supervisory scrutiny”.

The high barriers to entry to FISPs may exclude smaller financial institutions and other private actors which may nevertheless be vulnerable to illicit finance risks. Resourcing challenges therefore entail limitations to the volume of information shared as well as a small number of private sector participants relative to the total number of obliged entities, with membership often concentrated in the retail banking sector (Keatinge 2017).

Derisking

Financial institutions are obliged to refrain from entering into business relationships when they are unable to perform the appropriate customer due diligence (European Commission 2022: 15). In what is known as de-risking, some institutions may then choose to terminate or restrict business relationships with clients or categories of clients, which have unintended consequences for financial inclusion and contractual rights.

This may also be the case for information shared under FISPs. Vogel (2022: 57) cautions that if information shared under an FISP influences a private sector’s decision to terminate a business relationship, the affected party may be able to attribute such consequences to the state and claim to have suffered discriminatory treatment at its hands. The European Commission has recommended that FISPs should respect contractual clauses and the rights and obligations of both parties to a business relationship (European Commission 2022: 15).

At the same time, it is also important that financial institutions do not jeopardise investigative actions by prematurely terminating business relationships or undertaking other actions unless this has been agreed in advance with law enforcement actors. In this respect, the EFIPPP (2025b: 14) describes how FISPs can help manage this risk, for example where law enforcement agencies file “keep open” requests to the respective financial institution to refrain from closing the account at the risk of compromising the investigation.

Voluntary approaches versus strengthening existing obligations and capacities

Some commentators highlight the existence of a tension between FISPs and the general AML/CTF frameworks, expressing concerns that the former may take away from law enforcement’s responsibilities and private sector entities’ standard reporting obligations under the latter. It has been emphasised that FISPs should not amount to “an outsourcing of investigative functions” from public to private entities (EFIPPP 2025a: 8).

Many have pointed out that FISPs would not be strictly necessary if public authorities’ capacities to fulfil their envisioned role under the FATF system were enhanced. For example, law enforcement agencies have their own means to access – subject to the provisions of data protection legislation and the appropriate legal safeguards – the information they need to conduct their investigations without the need for FISPs; for example, filing warrants or disclosure orders against financial institutions. Prior to the existence of FISPs, FIUs and law enforcement also used a variety of methods to communicate with private sector entities, such as establishing contact groups and disseminating alerts and guidance to the regulated sectors (Artingstall and Maxwell 2017: 10). Lastly, obliged entities can already – again in accordance with the law – provide as much information to FIUs as they wish on a voluntary basis as part of their standard reporting obligations.

Vogel (2022: 56) asks policymakers to consider the possibility that:

“[F]ailures in the detection of criminal assets are frequently not the result of insufficient compliance efforts on the part of the private sector but rather the result of insufficient performance by, and underlying inadequate resourcing of, public authorities when it comes to the assessment of the information reported by obliged entities.”

Vogel (2022: 54) argues that rather than increase reliance on voluntary inputs from these actors, efforts should be directed towards improving deficiencies in the existent legal framework. He suggests this may ultimately be more sustainable in any case given that the voluntary and informal information sharing under FISPs might be more liable to be legally challenged (Vogel 2022: 55). Similarly, Fisher (2024: 88) suggests improved regulation – for example, to make good quality STR reporting a legal obligation with more stringently enforced penalties for failures to comply – could obviate the need for FISPs.

Data protection

One of the most significant challenges faced by FISPs is to maintain their effectiveness and ambition in terms of information exchange while complying with data protection law. According to Vogel (2022: 57) the existing AML/CFT framework already “frequently struggles to find the right balance between criminal policy needs and data protection law” and this can be more challenging with FISPs given the more informal nature of information sharing taking place.

As discussed, the provision of tactical intelligence between obliged entities and law enforcement authorities may contain personal data relating to the account holder, account information and transaction data, among other things. Vogel (2022: 57) notes that since such the main purpose of such information is “the identification of criminal suspicion and thus the initiation of criminal proceedings”, processing this data should be treated with corresponding levels of gravity.

The extent to which such information sharing complies with data protection law often hinges on whether or not there is an exemption provided in AML instruments to do so and, even then, a necessity and proportionality threshold may need to be met (Vogel and Lassalle 2023).

This may differ from one domestic legal framework to another. Kosta et al. (2024: 30-31) conducted an analysis of information sharing undertaken by the Fintell Alliance in the Netherlands into the legality of sharing personal data as requested by law enforcement agencies under the normal AML framework as opposed to the informal FISP setup. They found that while the alliance did not have its own legal framework for sharing personal data, the fact that the alliance is run by the Dutch FIU meant that data transfers could be justified with reference to the rights and obligations enjoyed by the FIU under the main AML legal instrument (the Wwft). Therefore, they conclude that the alliance does not violate data protection regulations.

However, commentators have expressed more doubts about FISPs’ compliance with the European data protection frameworks, notably the general data protection regulation (GDPR). In their analysis, Brewczyńska and Kosta (2024) concluded that voluntary or informal data exchanges – especially those that pertain to individuals – are not covered by GDPR’s lawful-processing principles (Articles 6–9) and violate requirements for necessity, proportionality and purpose limitation. Furthermore, they note that FISPs often do not have clear roles defined as data “controller” or “processor” as mandated by the GDPR (Brewczyńska and Kosta 2024: 479).

The European Data Protection Board (2023) penned a letter to the EU institutions on data sharing for AML purposes that also flagged significant concerns. It emphasised that countering crime is a public task and that “limiting the flow of information from obliged entities to public authorities constitutes a safeguard for individuals”; on this basis the board argues that the processing of information arising from STRs – given their sensitive nature – should be limited to public authorities.

In terms of the future outlook, Vogel et al. (2024: 7) argue that the “[t]he uncertainty surrounding the interaction of the [AML and data protection] frameworks would become even more problematic if public-private information sharing were to lead to an even more comprehensive, and therefore more intrusive, processing of customer data [such as bulk transfers]”. Elsewhere, Vogel (2022: 57) has called for more efforts to define appropriate rules for public-private information sharing to ensure it becomes more effective and legally sustainable. Aidoo (2025: 19) argues that emerging privacy-enhancing technologies – such as the tokenisation of personal data where identifiers are replaced by tokens – may be able to address at least some confidentiality issues.

Potential tensions between public and private interests

Some commentators have flagged concerns that the motivation of private actors to participate in FISPs may not always be well intentioned and their interests may conflict with the public interest as served by the public actors. Knust (2024: 111-14) describes how in theory FISPs work through interdependence, relying on both law enforcement’s mandate to investigate financial crime and private sector actors’ desire to minimise the damage illicit finance can cause to their commercial interests. At the same time, they note that the logic private sector actors follow is largely dictated by profitmaking and that this can lead to misalignment.

Indeed, various potential kinds of tensions in this regard have been identified in the wider literature. For example, public stakeholders consulted as part of a European Commission study (2022: 17) warn that some of the information shared in FISPs could conceivably be used to provide select market participants with a competitive advantage and therefore lead to a distortion of competition.

Vogel (2022: 55) argues that in cases where a small number of entities are involved in priority setting for FISPs, it is possible that the agreed priorities, which are applied system-wide, may reflect the commercial interests of the few rather than public interest objectives more broadly. As discussed, private sector participation in FISPs is often limited to a small sub-section of entities, most frequently large multinational retail banks, who therefore may have been able to influence public priorities.

Vogel recommends that priorities are set based on impartial, public interest focused policy considerations and are, for example, informed by objective evidence on the most relevant criminal threats (Vogel 2022: 55). Keatinge (2017) notes that FISPs have been encouraged to open up not only to a more diverse group of financial institutions but also to civil society organisations that could support with data protection and transparency concerns.

Within FISPs, private sector entities have dual roles as a participant in an exercise in voluntary information exchange and as a regulated entity subject to enforcement requirements. Fisher (2024: 89) highlights an important distinction in this regard:

“With voluntary disclosure, the private sector controls what information is disclosed. With compelled disclosure, the information sought is listed by the law enforcement authority.”

They explain that if oversight is reduced and a wide discretion is accorded to private sector entities, it can enable them to “conceal any vulnerabilities in terms of inadequate customer-due-diligence material or complicit involvement” (Fisher 2024: 89). More generally, regardless of how much information is withheld in a voluntary disclosure, the participation of a financial institution as a valuable collaborator within the framework of an FISP might make regulators less likely to apply the full force of a regulatory enforcement action or indeed to investigate compliance failures at all. Indeed, a law firm has revealingly cited the need to “minimize…risk of an enforcement action taken against the bank for AML failures” as a major incentive to participate in an FISP (Anderson et al. 2021).

The European Commission (2022: 16) warns that the information shared may also give an insight into the investigative techniques and strategies of law enforcement authorities, which if leaked, could undermine wider financial crime investigatory efforts. In some FISPs such as the JMLIT+, there are due diligence vetting processes in place for all applicant members, who are also made to sign trust and confidentiality agreements to prevent them from leaking information (EFIPPP 2025b: 21).

- For a recent overview of such partnerships, see Maxwell, N. 2025. A new era of private sector collaboration to fight economic crime.

- While in some cases the terms information and intelligence are used interchangeably, Artingstall (2016) explains that intelligence is typically understood to refer to information which has “gone through a process of analysis and production, from which decisions on action can be made and conclusions drawn”. Given that not all information shared through FISPs necessarily undergoes such a process, this Helpdesk Answer primarily refers to information sharing unless otherwise stated.

- Swiss authorities commissioned a review which found that when the PPP term is used in international financial circles, it is normally taken to mean “public-private financial information sharing partnership[s]” which is often abbreviated to FISPs (Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland 2023: 2). For the sake of greater clarity, this Helpdesk Answer uses the term FISP, even where the term PPP is used in the literature.

- The FATF Recommendations call for national legal frameworks to impose reporting obligations on financial institutions – such as banks, securities firms and money services businesses – as well as so-called designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs), which includes real estate agents, lawyers and accountants.

- For example, under Article 46 of the EU directive 2015/849 of the European Parliament and Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, national governments are simply asked to “ensure that, where practicable, timely feedback on the effectiveness of and follow-up to reports of suspected money laundering or terrorist financing is provided to obliged entities”. In a national example, Article 41(2) of the German AML lawonly states that the national FIU “shall provide the obligated party with feedback on the relevance of its report within a reasonable time”.

- That being said, it has been argued that the fact that FISPs are grounded on voluntary exchanges, as opposed to the legal nature of obligations, this can lead to conceptual confusion and even tensions if not well managed (Vogel 2022). This is discussed in further detail in the “Challenges and concerns” section below.

- For example, Maxwell (2020: 13) found that, as of 2020, the mandate of FISPs such as the Argentina Fintel-AR and the Germany Anti Financial Crime Alliance was limited to exchanging strategic information.

- In its mutual evaluation report of the UK, the FATF commended JMLIT as “an innovative model for public/private information sharing that has generated very positive results since its inception in 2015 and is considered to be an example of best practice” (FATF 2018: 6).

- These were Afghanistan, Argentina, Australia, Colombia, France, Georgia, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates (UNCAC Coalition 2016). The desk review for this Helpdesk Answer did not identify any publicly available follow-up review of these countries’ progress against this commitment.

- These five FISPs were selected based largely on the basis of volume of information available on their key characteristics and effectiveness.

- JMLIT+ currently runs dedicated threat groups for fraud, money laundering, tax crime and evasion and terrorist financing (EFIPPP 2025b: 13).

- In the Dutch system, the term “unusual transaction report” is used in place of suspicious transaction report.

- However, according to a study commissioned by the EFIPPP (2025a: 22), whenArticle 75 of Regulation (EU) 2024/1624 comes into force in 2027, there may be a stronger legal basis across the EU to do so.