Query

Please provide an overview of Ecuador’s anti-corruption framework, with a focus on preventive measures and corruption risk management in public administration.

Caveat

This Helpdesk Answer is written in the English language, although many of the key sources on which it draws are available only in Spanish. Online translation tools were used for this purpose, and some language and diagrams are reproduced here in English. These tools can be error prone so the translations should be considered indicative rather than fully accurate.

Background

Ecuador is a country on the Pacific coast of South America with an estimated population of just over 18 million. It has faced long periods of military rule and economic upheaval. Its population is ethnically diverse and is characterised by a high degree of inequality (MacLeod et al. 2025). Its economy is strongly dependent on oil, making it particularly vulnerable to global economic shocks. It is also a major exporter of agricultural produce (International IDEA 2025). Ecuador’s economy contracted by 1.5% in the third quarter of 2024 compared to the same period in 2023, and the country faces a significant budget deficit (Chiriboga 2025).

The established presence and considerable influence of international criminal organisations and a dysfunctional prisons system have contributed to high levels of violence in Ecuador (International IDEA 2025). This has peaked in recent years; according to one estimate, the homicide rate increased by 430 percent from 2020 to 2025 (Goebertus 2025). In its 2024 country report on Ecuador, Freedom House notes that violent crime has a major impact on the functioning of the state and on citizens’ daily lives. At least 15 judges and prosecutors have been murdered since 2022 (Goebertus 2025). During the first four months of 2024, 92 attacks against journalists were recorded (CIVICUS 2024). Key governance challenges include due process violations and corruption implicating state officials (Freedom House 2024).

As a country that borders the world’s two largest producers of coca, Colombia and Peru, Ecuador is strategically placed to serve as a transit hub for the drugs trade. In 2024 it became the top exporter of cocaine to Europe, with Mexican drug cartels exploiting the country’s weak institutions and porous borders. In 2024, 6,818 homicides were recorded in Ecuador (Norwegian Refugee Council 2025).

Ecuador is a multiparty republic with a unicameral legislature. The president is both head of state and head of the government. The president and vice president are directly elected and serve four-year terms. Members of the cabinet are appointed by the president. Legislative power is vested in the national assembly, whose members are also elected to four-year terms. In a September 2008 referendum, voters approved a new constitution, which has subsequently been amended at several junctures (MacLeod et al. 2025).

Ecuadorian politics has long been characterised by instability, with the armed forces continuing to play a significant role in public life. The political landscape is fragmented, volatile and polarised. Between 1996 and 2023, most democratically elected presidents did not serve full terms. One exception was Rafael Correa

who served as president from 2007 to 2017, but who faced corruption allegations throughout his tenure. In 2020, an Ecuadorian court sentenced Correa – who was residing in Beligum – to eight years in prison in abstentia for accepting bribes from private firms in exchange for state contracts (BBC 2020).

In 2023, then-president Guillermo Lasso Mendoza made use of a constitutional clause27eedaad9bf2 to dissolve congress, and by doing so ended his presidential term (Atlantic Council 2023). The ensuing election campaign was marked by significant organised crime violence, including the assassination of candidate Fernando Villavicencio. In October 2023, Daniel Noboa Azín won the election to serve the remainder of Lasso’s term (Freedom House 2024). In January 2024, the new government made use of emergency powers to expand the role of the military. Noboa was re-elected in April 2025, defeating leftist candidate Luisa Gonzalez. Electoral observers considered that overall, the elections had been peaceful and transparent (International IDEA 2025).

Extent of corruption in Ecuador

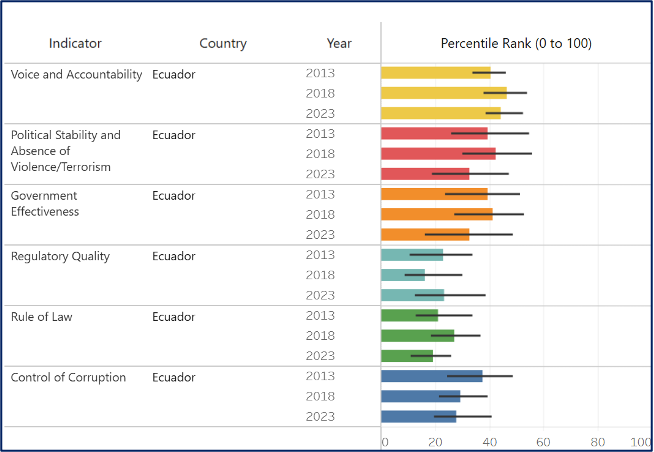

Corruption remains a major challenge in Ecuador, with global indicators pointing to deteriorating levels of corruption control in recent years. While the country largely experienced improving scores for the World Bank’s six Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) between 2013 and 2018, these subsequently mostly declined between 2018 and 2023, including for the rule of law and control of corruption indicators with an exception for regulatory quality.ebedd7b8fd90

Table 1: Ecuador’s scores on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) at 3-year intervals.

|

Indicator |

2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

|

Voice and accountability |

-0.25 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

|

Political stability |

-0.18 |

-0.09 |

-0.34 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.45 |

-0.32 |

-0.49 |

|

Regulatory quality |

-0.84 |

-0.89 |

-0.72 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.87 |

-0.66 |

-0.96 |

|

Control of corruption |

-0.50 |

-0.63 |

-0.65 |

Source: World Bank Group n.d.

Similar patterns can be observed in terms of Ecuador’s percentile rank727e56bf0545 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ecuador’s percentile rank on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators between 2013 and 2023

Source: World Bank Group n.d.

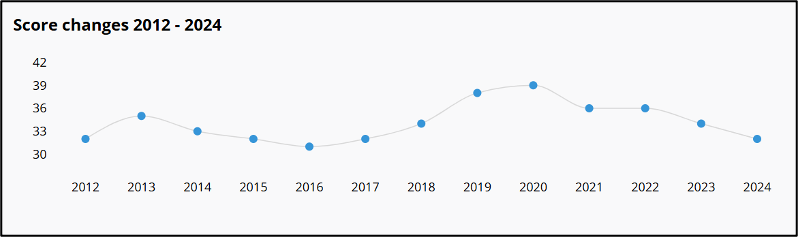

Ecuador consistently ranks poorly on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), which measures perceived levels of public sector corruption, scoring among the lowest in Latin America. It scored 32/100 in 2024, dropping from 36 in 2022 and a high of 39 in 2020 (see Figure 2) (Transparency International 2025).

Figure 2: Ecuador’s score on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) between 2012 and 2024

Source: Transparency International 2025

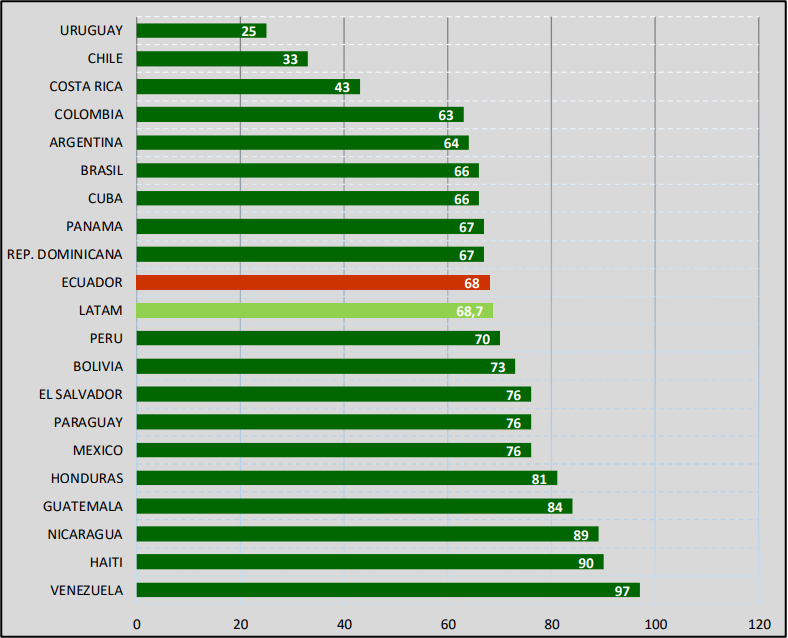

El Círculo de Estudios Latinoamericanos (CESLA) created a composite indicator on estimated corruption levels in Latin America. This indicator relies on different existing indices from organisations such as the World Bank, Transparency International and the World Economic Forum, and accorded Ecuador a score of 68 out of 100. While this puts Ecuador close to the estimated regional average, CESLA classifies any score from 61 to 80 as constituting ‘high levels of corruption and extremely weak anti-corruption policies’.

Figure 3: CESLA’s indicator for corruption levels in Latin America, July 2024

Source: CESLA 2024

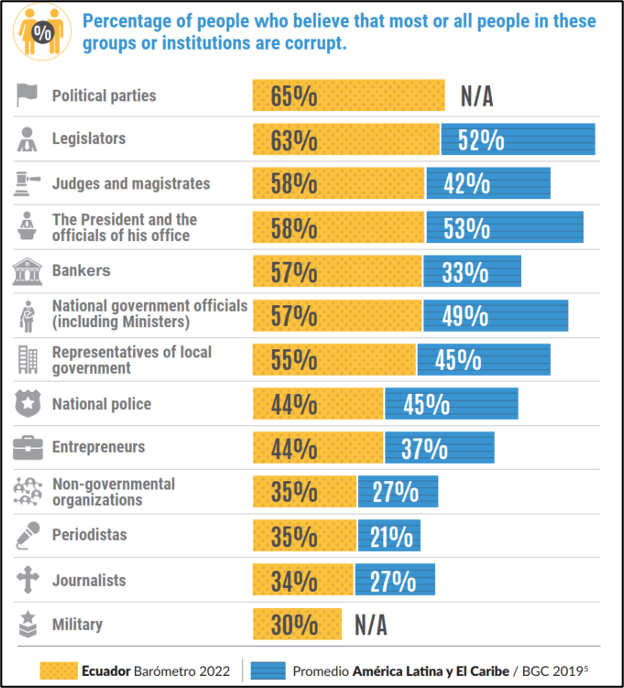

Recent survey data from Ecuador consistently indicates that citizens consider corruption to be a significant issue in their country. A 2021 survey by the Latinobarómetro Corporation showed that 72% of Ecuadorian respondents believed that the level of corruption in the country has increased in relation to the year prior to the survey (Corporación Latinobarómetro 2021). According to the 2022 Ecuador Corruption Barometer, 93% of Ecuadorian respondents believe corruption is a big or very big problem in their country (FCD and Transparency International 2023). The respondents also expressed their views on which kinds of groups and institutions they believed were most corrupt (see Figure 4). These results showed that political parties, legislators, the judiciary and members of the public administration are widely believed to behave in a corrupt manner. Furthermore, comparisons to a similar 2019 survey indicate a largely deteriorating trend across most categories of public official with the notable exception of police; for example, 57% of those surveyed in 2023 thinking most or all national government officials were corrupt, compared to 49% in 2019.

Figure 4: Results of a question from the 2023 Ecuador Corruption Barometer compared to a similar 2019 survey

Source: FCD and Transparency International 2023: 18

According to a 2022 survey conducted for the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), 65% of respondent businesses believed that corruption and largescale bribery in Ecuador had increased over the previous 24 months (CIPE 2022). Additionally, 68% of respondent businesses said they abstained from public procurement processes because competition was unfair (CIPE 2022). Other analyses have also flagged the high risk of corruption in public contracting in Ecuador, suggesting that lawmakers and interest groups collude over official appointments and the allocation of resources, compromising public integrity (BTI 2024).

In addition to indices and surveys, a recent string of high-profile cases indicates corruption risks, including cases implicating members of the executive branch and wider public administration. The Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo (FCD)9af007e7df24 points to a case in which weak conflict of interest regulations enabled the minister for the environment to grant a permit to a company owned by Ecuador and managed by the national president of the ruling National Democratic Action (ADN) party to develop a real estate project in a protected area. Furthermore, the environmental impact assessment for the project was contracted to a consulting firm in which another minister held shares (FCD 2024). A 2020 study found that gaps in the regulation of conflicts of interest also presented significant corruption risks at the lower levels of public administration (FCD, PADF and CSIS 2020: 5-6).

As well as domestic actors, corruption involving public officials in Ecuador can also be driven by multinational companies, especially those seeking a stake in the country’s natural resources and other sectors. In 2017, then vice president of Ecuador Jorge Glas was sentenced to six years in jail for taking U$13.5 million in bribes as part of an international grand corruption scheme spearheaded by the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht (BBC 2017). In 2024, a US court convicted the former comptroller general of Ecuador, Carlos Polit, for accepting up to US$10 million in bribes from Odebrecht in exchange for rescinding and refraining from imposing fines against them(US Department of Justice 2024). In a further example, in 2024, a Swiss trading house, Gunvor, was found guilty by courts in Switzerland and the United States of bribing Ecuadorian officials between 2013 and 2020 to facilitate their purchases of oil at below-market prices (Budry Carbó and Duparc 2024).

Several commentators have argued that enforcement against corruption is limited. Chiriboga (2025) argues that Ecuadorian law enforcement’s capacities were outdated and ill-equipped to take on the powerful organised crime networks operating in the country. Similarly, the judiciary reportedly struggles to adjudicate impartially; lower court judges have used habeas corpus to override criminal convictions, especially in cases involving drug trafficking and political corruption, thereby eroding public trust in the legal system (BTI 2024). According to BTI (2024), transparency activists and the media play a critical role in holding government and the judiciary to account, but they also face threats, particularly from criminal networks. Investigative journalism has uncovered high-level scandals, but this has not always resulted in adequate legal follow-up (BTI 2024).

Voss (2025) argues there has recently been a ‘historic anti-corruption push initiated by Ecuador’s [prosecutor general’s office]’ in the form of scaled up investigations and prosecutions, although conceding that this push has been met with political polarisation that may undermine its sustainability. Merino (2023: 46) highlights that many journalists, academics and legal analysts argue that prosecution for corruption can be selective, and in some instances, may amount to persecution against political opponents.

Between 2023 and 2024, action was taken in relation to the Encuentro,834f955bb13a Metastásisd46c88c264ab and Purga cases, which concerned various alleged corruption schemes implicating a total of 76 defendants, including judges, police officers, prison officials, lawyers, legislators, businessmen and politicians (The Cuenca Dispatch 2024). In October 2024, 30 individuals with alleged ties to drug lord Leandro Norero were ordered to stand trial for influencing appointments in the justice system and obtaining favourable court rulings (Reuters 2024a). In November 2024, 20 convictions were handed down (Reuters 2024b).

The OECD Public Integrity in Ecuador report (2021a) points out that Ecuador’s anti-corruption efforts have mostly focused on sanctioning individual instances of corruption, without addressing the underlying systemic issues that incentivise and enable corrupt behaviour. The OECD more generally recommends that policymakers ‘shift the focus from ad hoc integrity policies to a comprehensive, risk-based approach with an emphasis on cultivating a culture of integrity across the whole of society’ (OECD 2017b).

This Helpdesk Answer takes this risk-based approach as its point of departure to consider Ecuador’s approach to systematically preventing and managing corruption risks in its public administration. The paper first outlines Ecuador’s anti-corruption legal and institutional frameworks, charting the evolution of legislation, policies, institutions and bodies across the different branches of the state. It then focuses on corruption risk management measures more specifically, including by describing the different measures that public administration entities are obliged to undertake, both within their respective organisations, but also at a cross sectoral level. It subsequently summarises assessments of Ecuador’s system undertaken by the OECD, but also civil society actors, highlighting the various challenges and recommendations they have identified. Finally, informed by the challenges identified in the Ecuadorian context, the answer describes select approaches undertaken by other Latin American states to prevent and manage corruption risks in their respective public administrations.

Legal and institutional framework

Institutional actors

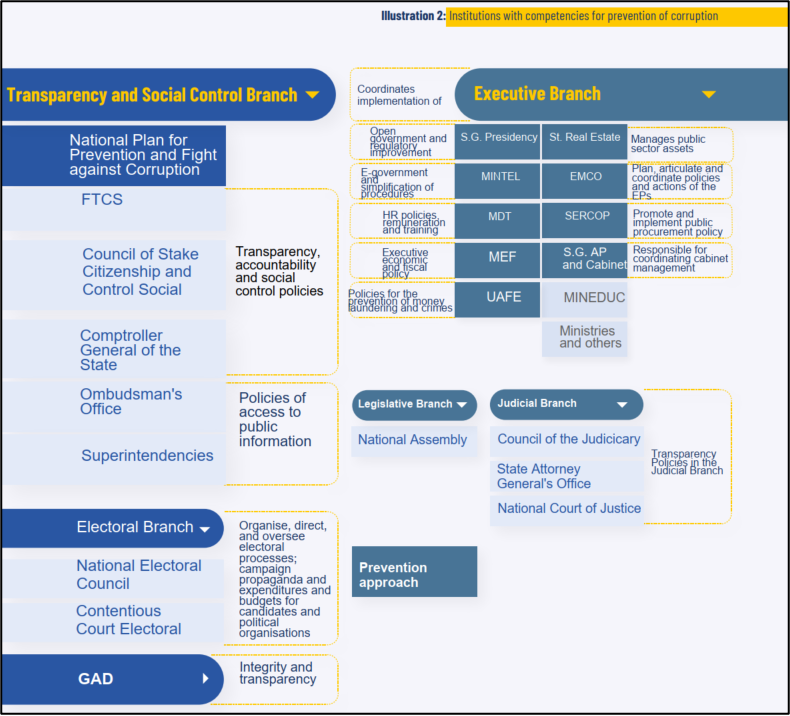

In Ecuador, roles and responsibilities for preventing and managing corruption risks in public administration are spread across multiple institutional actors (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Overview of institutional actors with a role in preventing corruption as listed in the PNIP

These institutional actors are located across the five branches of the state – electoral, legislative, executive, transparency and social control, and judicial – which are set out in the 2008 Constitution. The actors most relevant for control of corruption within the public administration are found within the latter three branches.

Executive

Within the executive branch, the general secretariat of public integrity (Secretaría General de Integridad Pública) is part of the presidency of the republic and is responsible for the management, monitoring and evaluation of the implementation of the national public integrity policya5ac9d0e1bd4 and coordinates entities of the executive branch as well with the other four branches (Presidencia de la República 2024).

It was established in 2024, but was previously known as the secretariat of anti-corruption public policy, and before that the general anti-corruption secretariat. In 2019, the presidency’s anti-corruption secretariat was created with competencies for coordinating measures to counter corruption. However, this was met with resistance from other state entities, which complained about the duplication of effort and interference in the functions of the judiciary, leading to the secretariat’s dissolution in the same year (Desfrancois 2022). In its short time of operation, the secretariat had three different heads (FCD and UNCACC 2021: 21).

Other executive bodies have specific functions within the anti-corruption framework. For example, the Ministry of Labour (Ministerio del Trabajo) is responsible for policies on employment and human resources in the public sector, including recruitment, promotions, capacity building and disciplinary aspects (OECD 2021a). The Ministry of Economy and Finance (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas) reports to the comptroller general’s office and other supervisory authorities in instances of non-compliance with the Organic Code of Planning and Public Finance (Presidencia de la República 2024). The financial and economic analysis unit (Unidad de Análisis Financiero y Económico – UAFE), an autonomous technical entity of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, is responsible for the implementation of policies and national strategies for the prevention and identification of money laundering and financing of crimes (OECD 2021a). It serves as Ecuador’s financial intelligence unit (FIU) and, since 2016, has been a member of the Egmont Group.

The national service of public procurement (Servicio Nacional de Contratación Pública – SERCOP) is responsible for advising contracting entities and training suppliers of the national public procurement system on the application of the rules governing the system’s contracting procedures, as well as for analysing and monitoring all public procurement processes, including identifying any suspected irregularities (Presidencia de la República 2024).

While SERCOP plays more of a coordination role for public contracting, every public administration body independently manages the contracting process within its own budget and referral terms (US International Trade Administration 2024). Moreover, each executive ministry or agency is responsible for overseeing the implementation of certain anti-corruption and integrity policies within its internal operations, as described in further detail below.

Transparency and social control

The role of the transparency and social control branch(Función de Transparencia y Control Social - FTCS) is to promote and encourage the control of public sector entities, including in efforts to curb corruption (OECD 2021a: 22). The branch is overseen by the coordination committee (Comité de Coordinación) which is composed of the heads of nine FTCS entitiesc7fdec4ef073, with the support of a technical secretariat (FTCS 2024: 51). According to Article 206 of the constitution, the coordination committee must ‘formulate public policies of transparency, control, accountability, promotion of citizen participation and prevention of and fight against corruption’ and ‘develop a national plan to fight corruption’ (FCD and UNCACC 2021: 19). Furthermore, it should ensure that all entities work together to implement transparency and anti-corruption policies (FTCS 2024: 51).

The council of citizen participation and social control (Consejo de Participación Ciudadana y Control Social) is a powerful entity within the FTCS; its duties include promoting public participation and countering corruption; establishing accountability mechanisms for public sector institutions and entities, such as citizen oversight and social monitoring bodies; and investigating ‘reports about deeds or omissions affecting public participation or leading to corruption’. The council designates the heads of several public institutions, including the attorney general, the ombudsman, the public defender, the prosecutor general and the comptroller general (OECD 2021a: 23). Depending on the role, these are either designated by the council from a shortlist proposed by the executive government or other relevant bodies, or by citizen selection committees organised by the council (Consejo de Participación Ciudadana y Control Social n.d.). The designation process generally faces reported delays and it has been argued can be vulnerable to political manipulation (Noboa 2025).

Another entity is the office of the comptroller general (Contraloría General del Estado), which operates a state control, oversight and audit system with a view to verifying public institutions’ compliance with their mandates and ensuring the proper management of public resources. The office of the comptroller general’s duties include overseeing the internal and external auditing of public sector institutions and private sector entities; determining cases of administrative and civil negligence; and collecting evidence of criminal liability regarding activities under its control (OECD 2021a: 23).

Two other relevant entities within this branch are the superintendency of information and communication (Superintendencias de Información y Comunicación) and the ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo) which have competences for guaranteeing access to public information(OECD 2021a: 24).

Judicial

Within the judicial branch, the office of the prosecutor general (Fiscalía General del Estado) directs criminal investigations and proceedings. Its transparency and anti-corruption unit leads criminal investigation into suspected acts of corruption as well as acts that undermine transparency in public life. The public administration unit investigates suspected acts of embezzlement, bribery, illicit enrichment and extortion (OECD 2021a: 24)

Legislation and policies

Ecuador’s anti-corruption framework comprises international treaty commitments, domestic legal instruments (laws, decrees, regulations) and a patchwork of strategies, policies and action plans. Ecuador is a signatory to the 2003 United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), the 1996 Inter-American Convention against Corruption (IACAC), as well as to the Lima Commitment issued at the Eighth Summit of the Americas in 2018, which outlines 57 non-binding commitments focused on preventing and countering corruption through improved democratic governance (Presidencia de la República 2024).

In recent years, there has been a surge in legislative and policy initiatives designed to address corruption, many of which incorporate a strong focus on preventive measures and mainstreaming integrity across the public administration. Nevertheless, the number of new initiatives, some of which were introduced to replace others before their originally planned expiration period, has arguably led to a complex framework susceptible to fragmentation and duplication.

Constitution

Ecuador’s 2008 constitution, most recently amended in 2024, introduced key principles such as transparency, accountability and citizen oversight into Ecuador’s public administration system (Presidencia de la República 2024 and Constitute Project 2025). It also created the transparency and social control function – one of the five branches of government.

The constitution stipulates in Article 8.3 that the state’s primary duties include guaranteeing its inhabitants the right to live in a democratic society free of corruption. Article 230 prohibits nepotism in public office. Article 231 sets out the requirement for public officials to submit asset declarations, requiring them to submit a sworn statement of net worth at the beginning and end of their term in office. Article 232 deals with conflicts of interest, making it clear that officials who have vested interests in economic activities that are subject to government monitoring or control cannot themselves be responsible for controlling or regulating those activities.

Article 233 lays down rules for misconduct in public office. It makes it clear that all public servants are accountable for their actions and will be held liable for the management and administration of public assets. Individuals who have been convicted of crimes such as embezzlement, illicit enrichment, extortion, bribery, influence peddling, money laundering and corruption-related organised crime are banned from running for public office and from taking part in public procurement processes.

Criminal code

The Comprehensive Organic Criminal Code (Código Orgánico Integral Penal –COIP) was first enacted in 2014 and revised in 2020 and 2021. While the COIP does not define corruption, it outlines certain acts of corruption such as embezzlement, bribery, extortion and illicit enrichment. Furthermore, the amendments in 2020 and 2021 introduced new corruption-related offences, including: obstruction of justice; overpricing in public procurement; and bribery in the private sector (Asamblea Nacional 2013 and 2022; Ecuador Transparente 2022).

Public procurement legislation

Public procurement is governed by the 2008 Organic Law of the National Public Procurement System (Ley Orgánica del Sistema Nacional de Contratación Pública –LOSNCP). It mandates the use of an online platform (the Portal de Compras Públicas) to manage procurement processes electronically (Superintendencia de Ordenamiento Territorial, Uso y Gestión del Suelo 2025). In 2017, SERCOP, the entity responsible for overseeing the national procurement system, began implementing ISO 37001 to introduce an anti-bribery management system to public procurement processes (IsoTools 2017).

Amendments were made to public procurement legislation in 2024 with a view to curbing corruption and money laundering (Bedoya 2024). Innovations included the establishment of an anti-money laundering and anti-corruption unit within SERCOP and the formation of citizen observatories.Furthermore, thelaw was modified to prevent abuse of contracting procedures between multiple government entities and private suppliers (known as ‘inter-administrative contracting’)including by prohibiting the formation of consortia for these purposes. The reform also updated the definition of collusion in contracting and established the possibility of suspending contracts where there are indications that collusive practices have occurred (Bedoya 2024).

Anti-money laundering (AML)

First enacted in 2016, the Organic Law on Prevention, Detection and Eradication of Money Laundering (Ley Orgánica para la Prevención, Detección y Erradicación del Delito de Blanqueo de Capitales) obliges both financial and certain non-financial entities to establish preventive programmes, file suspicious transaction reports, and respond to oversight by the UAFE. It applies to a broad range of entities including banks, insurers, real estate agents, notaries and virtual asset providers.

However, public sector actors are also increasingly subject to AML obligations in Ecuador. A new anti-money laundering law is set to enter into force on 29 July 2025. It provides for a broad institutional restructuring, including the establishment of a national coordination council against money laundering and its preceding crimes, the financing of terrorism, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (Consejo Nacional de Coordinación contra el Lavado de Activos y sus Delitos Precedentes, la Financiación del Terrorismo y de la Proliferación de Armas de Destrucción Masiva denominado – CONCLAFT) (El Informativo 2025). Obliged entities include central government agencies, decentralised autonomous governments (GADs), political parties and movements, public enterprises, and public banks and social security entities. These are required to implement internal control and compliance programmes, appoint a compliance officer, file suspicious transaction reports when irregularities arise and conduct risk-based due diligence for contracts and suppliers. The law works alongside Ecuador’s public procurement legislation by requiring contracting entities to verify supplier backgrounds against UAFE alerts or red flags. Public officials and institutions face civil, administrative and criminal penalties for non-compliance (Registro Oficial 2024).

Transparency and access to information

Ecuador’s Organic Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information (Ley Organica De Transparencia Y Acceso A La Informacion Publica –LOTAIP) was first enacted in 2004. It was revised in 2009 and again in 2023 to emphasise proactive transparency, centralised portals and open data formats. It guarantees access to ‘any document in any format’ held by public institutions and private entities receiving and implementing public resources. It also promotes citizen participation and accountability by stipulating proactive publication of key institutional data such as budgets, contracts, organisational structure, personnel directories, salaries and audit results (López Carballo 2013; Cuenca 2023). The LOTAIP stipulates that in the event an obligated entity does not provide the requested information in compliance with the law, the ombudsman is responsible for intervening and decisiding on corrective measures.

Administrative law

The Organic Administrative Code (Codigo Organico Administrativo –COA)sets out obligations with which members of public administration are required to comply when engaging in administrative procedures and managing state finances. The Organic Code of Planning and Public Finance (Código Orgánico de Planificación y Finanzas Públicas– COPLAFIP) also establishes transparency and other requirements for the management of public resources (FTCS 2024: 34).

Law of public services and code of ethics

The Organic Law of Public Services (Ley Orgánica de Servicio Público –LOSEP), enacted in 2010, is Ecuador’s central framework governing public servants’ duties. Article 22 of the LOSEP requires officials to administer public resources efficiently and in accordance with the law. It applies uniformly across all branches and levels of government, public enterprises and public banking institutions. The LOSEP aims to professionalise public service through merit-based recruitment (including through competitive examinations) and by enhancing transparency, efficiency and quality in public administration (Ecuador Legal 2025).

In 2021, a code of ethics (Código de Ética) was decreed by President Lasso. This was applicable to all public administration entities, which were mandated to create internal rules to implement the decree (Flores Vera 2022). It included a ban on remunerating the spouses of the president and vice president; it prohibited the nomination of relatives of executive branch officials to government positions; it required a pre-emptive declaration of potential conflicts of interest; and it prohibited the unofficial use of official aircraft, vehicles and government property (US Department of State 2025).

However, the decree was rescinded by President Noboa when he took office. In December 2023, President Noboa decreed a new code of ethics, which similarly included rules on nepotism, gifts, personal use of state assets and limits on appointing relatives to state roles. However, he issued another decree rescinding the new code in February 2024, offering no justification for this decision, but stating that it was the president’s responsibility to ‘direct the public administration’ (Primicias 2024a).

Internal control standards

The general comptroller’s office of the state periodically issues internal control standards for entities, organisations of the public sector and legal entities of private law that receive public resources. In 2023, it issued technical standard no. 200-1 on

integrity and ethical values (200-01 Integridad y valores éticos),which, among other things, stipulated that the highest authority in each entity managing public resources was responsible for issuing the code of ethics and adopting tools to prevent and manage integrity risks and conflicts of interest to contribute to the proper use of public resources and measures against corruption within their entity (Presidencia de la República 2024: 4).

ISO 37001

ISO 37001 is an international standard dedicated to establishing, implementing, maintaining and improving an anti-bribery management system within an organisation, with a focus on risk management (Endara 2019). In the late 2010s, a multistakeholder committee involving over 40 executive branch entities was set up to adopt and implement ISO 37001 in the Ecuadorian public sector (Endara 2019). Different institutions then set up internal bodies to implement and monitor the standard. For example the Ministry of Economy and Finance created an anti-corruption committee that regularly reviewed bribery risks within the ministry, identified through the implementation of the anti-bribery management system (OECD 2021a: 55).

2022 national anti-corruption strategy/national public integrity policy 2030

In 2022, President Lasso presented a national anti-corruption strategy (Estrategia Nacional Anticorrupción), with the objective of developing a coordinated framework to counter corruption and strengthen public integrity. The strategy recognises corruption as a systemic problem that damages trust, undermines governance, increases transaction costs and obstructs public investment. It frames corruption as not just a legal issue but also a cultural, institutional and ethical crisis. In response, it stresses the need for public integrity, transparency and ethical leadership at all levels of the public administration.

The strategy also recognised several systemic weaknesses within Ecuador’s system that needed to be addressed: weak and fragmented oversight institutions; a lack of consistent public ethics codes and enforcement; over-centralisation; low-quality regulation; vulnerability to influence peddling and nepotism; and normalisation of corruption in certain segments of society and governance. To achieve this, the strategy sets out eight areas for government action (Presidencia de la República 2022; Primicias 2022):

- raising awareness of corruption’s causes and consequences

- promoting shared responsibility across sectors

- targeting corruption in high-risk, high-impact areas

- preventing and managing conflicts of interest

- ensuring transparency in public spending

- building institutional capacity for prevention and enforcement

- promoting transparent and responsible public procurement

- countering transnational corruption

(Presidencia de la República 2022; Primicias 2022)

In July 2024, the strategy formulated under President Lasso was transformed by President Noboa into the national public integrity policy 2030 (Política Nacional de Integridad Pública –PNIP). This formalised the eight strategic objectives, making them mandatory for all executive branch entities (Primicias 2024b). One of the stated goals of the PNIP is to:

‘[T]o create transparency and integrity pacts, generate institutional anti-corruption strategies in prioritised public entities within the executive branch, coordinate national policy with entities from other branches of government and decentralised autonomous governments, and forge alliances between the public and private sectors to fight corruption.’ (Presidencia de la República 2024: 60)

The formulation and monitoring of the PNIP is coordinated by the general secretariat of public integrity (Presidencia de la República 2024: 38). The PNIP was created through a consultative process involving different representatives of the executive branch, with support from a technical team involving the international AC expert Robert Klitgaard and experts from UNDP (Presidencia de la República 2024: 23).

The PNIP explicitly acknowledges the findings of the 2021 OECD assessment report on public integrity in Ecuador,311913874c3e stating (Presidencia de la República 2024: 13, 38):

‘Based on the OECD report, the lack of a national system for public integrity and the fight against corruption is evident, thus raising the need for its creation to consolidate the first pillar of public integrity

in Ecuador.’

As described in further detail below, risk identification and management is a key emphasis of the integrity system envisioned under the PNIP. As such, stateentities are obliged to assess their risk environment, identify corruption risks and undertake measures to manage them (Presidencia de la República 2024: 22).

The national plan for public integrity and the fight against corruption 2024-2028 (PNIPLCC)

In December 2024, the national public integrity and anti‑corruption plan 2024–2028 (El Plan Nacional de Integridad Pública y Lucha contra la Corrupción 2024-2028 –PNIPLCC)was launched. In contrast to the PNIP, the formulation and monitoring of the PNIPLCC is coordinated by the FTCS coordination committee (FTCS 2024: 3), but it still applies to all five branches of the state, including executive bodies (FTCS 2024: 52-55).

As with the PNIP, the PNIPLCC recognises the importance of a public integrity approach as promoted by the OECD (FTCS 2024: 19). It also acknowledges the coordination challenges Ecuador’s system faced in the past, as well as the fragmentation and politicisation of institutions which have led to inconsistent and at times selective enforcement (FTCS 2024: 41).

The PNIPLCC is structured around three pillars: public and private integrity; transparency and accountability; and citizen participation and integrity promotion (El Universo 2024)d185fbbf7fb9. Under the first pillar, the PNIPLCC aims to (FTCS 2024: 65):

‘[S]trengthen institutional and legal capacities to prevent and combat corruption by creating specialised structures, promoting integrity, and implementing mechanisms for monitoring and managing corruption risks in both the public and private sectors.’

The PNIPLCC then outlines 14 actions to achieve these goals, setting out responsibilities and timelines for implementation until 2028 (FTCS 2024: 70-79):

- the creation of the national integrity system3955573d047b

- establishment of institutional integrity units (IUI)e87c9b1ed8f6

- public institutions to implement integrity self-assessment processes

- development of an application/guide to ethical dilemmas for different sectors

- record of corporate compliance on integrity issues

- promote the national assembly’s approval of anti-corruption and conflict of interest laws

- establish the public service integrity forum

- establish the business sector integrity forum

- develop and implement methodologies for identifying and managing corruption risk

- strengthen the internal control systems of public administration

- design and implement a dissemination, training and education plan

- induction programme for entry into public service

- create a laboratory for the identification and prioritisation of money laundering risks

- strengthen administrative simplification in the public service

Public Integrity Law 2025

In May 2025, President Noboa submitted a bill on reforms to public procurement. The national assembly reportedly expanded the scope of the bill significantly, which resulted in a ‘legal medley’ (Primicias 2025). In June 2025, the assembly approved the new Public Integrity Law (Ley Orgánica de Integridad Pública). The law focuses on various goals, including eradicating violence and corruption within the public administration and improving public sector efficiency (Human Rights Watch 2025), and has four key areas: public procurement, institutional strengthening, public management, and the eradication of criminal networks (Lexis 2025). It makes amendments to up to 20 existing legal instruments (Lexis 2025).

The act introduces more severe sanctions for corruption-related offences, more verification requirements during public procurement, as well as strengthening the ability of oversight bodies to conduct audits into the use of public funds (Hayu 2025).

However, some aspects of the law have attracted significant controversy; for example, clauses increasing punitive sentences for crimes committed by children linked to organised criminal groups (Human Rights Watch 2025) as well as clauses that could allow the president to dissolve public companies created by law (La Derecha Diario 2025).

Corruption risk management

The U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre describes corruption risk management (CRM) as a process which takes place primarily at the organisational level:

‘Corruption risk management is a process to identify, assess and mitigate corruption risks within an organisation and its activities. It is also a way to analyse causes for corruption and ultimately to implement and manage corrective and preventive measures to curb corruption risks. (...) It is an important part of implementing anti-corruption policy. CRM holds a strategic dimension, as it implies backing from the top leadership and is integral to all decisions and activities of an organisation, from the institutional level to projects and programmes. (...) At the institutional level, CRM is helpful in coordinating integrity and compliance policies, in defining rules and procedures, and in determining proper control.’ (U4 2025)

The approach generally follows three main steps: risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation (U4 2025). Corruption risk management is therefore largely a preventive approach, but risk mitigation also requires reactive measures, such as investigative responses and corrective actions following the documentation of a corruption risk that has materialized in a concrete case (U4 2025).

In Ecuador, corruption risk management processes have formally been embedded at various levels of public administration. This includes internally-orientated processes at the organisational level. For example, many public entities are obliged to implement ISO 37001, the internal risk management approach specifically targeting bribery. Additionally, under the Organic Law of the State Comptroller General, each public sector institution that manages public resources is obliged to establish an organised, independent and well-resourced internal audit unit to conduct risk management processes, which areoverseen by the office of the comptroller general (OECD 2021a: 59-60).

Furthermore, in 2022, the now defunct secretariat of anti-corruption public policy launched a corruption risk methodology for 30 executive branch entities to implement self-assessment and mapping methodologies for institutional corruption risks (Metodologías de Autodiagnóstico y Mapeo de Riesgos Institucionales de Corrupción – MAMRIC) (Presidencia de la República del Ecuador 2022b). Senior managers within these entities were mandated to carry out a self-assessment of corruption risks in their internal operations and to develop strategies and actions in response (OEA/MESICIC 2024: 3; Estrategia Nacional Contra la Corrupción 2022: 31).

In general, there appear to be few studies assessing either: (i) the effectiveness of existing corruption risk assessment efforts in Ecuador; or (ii) the extent to which they are implemented consistently across public administration. The most prominent assessment was conducted by the OECD in 2021 when it evaluated the quality of corruption risk management conducted by internal audit units embedded in various public administrative bodies that manage public resources. The evaluators concluded that, while the corruption risk management procedures used were aligned with international standards in theory, in practice not all of these units were implementing risk management consistently (OECD 2021a: 59-60).

Some Ecuadorian agencies and initiatives have also used risk-based approaches to identify corruption risks at a cross-sectoral level, which is a different understanding of the approach as defined by U4. For example, the UAFE undertakes risk assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing across public entities and other private sector actors (OEA/MESICIC 2024: 1-2). Additionally, as part of the 2022 national anti-corruption strategy, risk assessments were undertaken by the then secretariat of anti-corruption public policy of 30 executive branch institutions, which resulted in nine institutions being classified as at high risk of corruption (Primicias 2022).58b57527d39c However, a recent OECD report concluded that the guidance issued to the institutions to conduct self-assessments of their exposure to corruption risks lacked specified methods to collect data and data sources (OECD 2025: 14).

There are many commitments related to corruption risk management in the recently adopted PNIP and PNIPLCC; these combine a mixture of institutional approaches that look within an organisation - in line with the U4 approach – and wider approaches which look across sectors, and the respective organisations and entities they contain.

The PNIP recognises the absence of an effective corruption risk management system in Ecuador (Presidencia de la República 2024: 72) and sets out to create:

‘[I]nter-institutional coordination scenarios to ensure, from a preventive perspective, the management of corruption risks, develop and support the implementation of a self-diagnosis methodology to map and mitigate institutional corruption risks, and develop typologies of corruption to inform the public.’ (Presidencia de la República 2024: 60)

As such, the PNIP sets out three key actions in this regard, which the general secretariat of public integrity is responsible for overseeing (Presidencia de la República 2024: 67; 84):

- develop corruption risk ‘maps’ detailing sectoral and national risks

- establish a methodology for identifying the modus operandi of alleged irregularities, violations of integrity and the proper management of corruption risks

- develop the regulatory framework for the management of corruption risks including through the appointment of specialised personnel

As a follow up to the second action, in mid-2025 the secretariat of public integrity published a new methodology for evaluating and managing corruption risks at the institutional level (MEGERIC). This is framed as a self-diagnosis tool for executive entities to identify and manage corruption risks within their organisation (Presidencia de la República 2025). The document describes the different stages of the risk management process, explaining the process and different sources of information which should be used to identify and classify risks, as well as mitigation measures (Presidencia de la República 2025). Under the planned implementation, the secretariat will train executive entities on the methodology; following this, within each entity, an institutional compliance officer will design a work plan and establish a working group to implement it (Presidencia de la República 2025: 17). Each entity will be obligated to provide outcome reports on the risk identification and assessment process, as well as actions plans which will be monitored periodically by their institutional compliance officer (Presidencia de la República 2025: 8).

Executive branches will be obligated to implement this methodology, producing a report summarising the initial corruption risk assessment and a Final report on the implementation of the Corruption Risk Identification and Assessment Process; and 2) Final report on the follow-up and monitoring of the action plans is envisioned that thehis tool must be impleacmented periodically and obligatorily by the Institutional Compliance Officer. I(Presidencia de la República 2025: 8)

The PNIPLCC contains a commitment to develop and implement methodologies to identify and manage corruption risks in public and private institutions, although it lists the office of comptroller general as the actor responsible for overseeing this (FTCS 2024: 75-76). The PNIPLCC envisions that the risk assessment methodology would be designed and rolled out to public sector entities by the end of 2028. Due to the absence of cross references to the PNIP made in the PNIPLCC, it was unclear from the desk review if there are plans to ensure there is no duplication across these different risk management methodologies.

Overview of assessments of Ecuador’s system

Various international, civil society and other observers have conducted assessments of Ecuador’s anti-corruption framework . These are summarised in this section but, as noted above, Ecuador’s system for preventing and managing corruption risks in public administration has undergone significant overhauls in recent years with, for example, the PNIP and PNIPLCC. Given how recent these are, this Helpdesk Answer was unable to identify any similar assessments on the effectiveness of newer initiatives, either in terms of their design or implementation.

OECD assessments

Although Ecuador is not currently in the OECD accession process, the OECD has conducted several country visits and commissioned several reports on the country as part of its public governance reviews series.

Andrade et al. (2023: 9) argue that the OECD reports and recommendations have greatly served Ecuador’s governing bodies and administrators in strengthening the country’s preventive approach to corruption. As noted above, Ecuadorian national stakeholders themselves have acknowledged the contribution of the OECD reports in shaping their new policies.

The OECD’s evaluations are premised on the concept of public integrity. This is defined in the 2017 OECD council recommendation on public integrity as the ‘consistent alignment of, and adherence to, shared ethical values, principles and norms for upholding and prioritising the public interest over private interests in the public sector’ (OECD 2017).

The OECD’s 2021 assessment report on Public Integrity in Ecuador: Towards a National Integrity Systemfound that Ecuador’s anti-corruption efforts had largely been focused on enforcement and sanctioning rather than on prevention or systemic reform. The evaluators also observed that the fragmented institutional framework and lack of political continuity hindered the development of an effective integrity system within the executive branch. It noted that ‘leadership for the integrity and anti-corruption agenda has been passed from one secretariat to another over the last few years’ (OECD 2021a:11). In reviewing the national public integrity and anti-corruption plan for 2019-2023 developed by the transparency and social control coordination committee, it found that the plan only contained minor references to entities from other branches, especially from the executive branch (OECD 2021a: 34).

In its executive summary, the report identified four key shortcomings in Ecuador’s then public integrity system (OECD 2021a: 4):

- Public integrity functions were dispersed across the five state branches (executive, legislative, judicial, electoral, and transparency and social control), with little coordination. Although some cooperation exists, especially in terms of enforcement, there was no system-wide mechanism for unifying strategies or promoting collaboration across institutions.

- Integrity related objectives in national plans, such as the public integrity and anti-corruption plan 2019-2023 and the national development plan 2017-2021,suffered from weak levels of ownership, a lack of follow-up and limited participation from the executive branch.

- Following its abolition in 2019, the anti-corruption secretariat was not replaced,2c7f255d9e6b leaving a gap in coordination. Other executive branch actors, such as the Ministry of Labour, were underutilised in terms of mainstreaming integrity.

- Tools for managing conflicts of interest, whistleblower protection and risk management were unevenly applied across ministries and lacked a unified, preventive focus.

In response, the report provided a roadmap for developing a comprehensive national integrity system based on five key recommendations (OECD 2021a: 5):

- Ecuador could create a national integrity and anti-corruption system, led by the president, that includes actors from all state branches and levels of government. The system should institutionalise dialogue with civil society, academia and the private sector.

- The national development plan 2021-2025 could be used to define a roadmap towards a national integrity and anti-corruption strategy for the 2023-2026 term.

- Ecuador could develop a long-term policy on integrity and anti-corruption to fulfil the constitutional anti-corruption duties of the state as well as to contribute to the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 16 and other international integrity and anti-corruption commitments.

- Ecuador could define clear integrity responsibilities within the executive branch by empowering the general secretariat of the presidency to coordinate prevention related aspects of integrity policy. At the same time, the mandate of the Ministry of Labour could be enhanced by tasking it with the promotion of a culture of integrity throughout the public sector.

While the OECD has not released a follow-up report on the implementation of these recommendations, many of these proposed steps appear to have been nominally endorsed through the adoption of the PNIP.

In 2024, the OECD published another report titled Promoting Public Integrity across Ecuadorian Society: Towards a National Integrity System, which takes a whole of society approach, and contains sections and recommendations on citizen participation, cultivating citizen commitments and the private sector (OECD 2024a). The report contained some similar findings to the 2021 report, for example, recognising there were still continuity challenges:

‘[R]epeated institutional changes of the main institution with responsibilities for public integrity in the Ecuadorian executive function have led to a lack of continuity in the efforts to promote public integrity in Ecuador and to consolidate a national public integrity system.’ (OECD 2024a: 16)

It also reiterated the need for enhanced coordination, noting that:

‘Ecuador could strengthen the inter-institutional coordination body[15]0766a47fb68c for the prevention of corruption to ensure strategic cooperation between the five state functions and all levels of government, with the contribution of civil society, academia and the private sector.’ (OECD 2024a: 19-20)

The OECD maintains a portal of OECD public integrity indicators (PIIs)to assess national anti-corruption and integrity systems; the indicators enable comparisons across participating countries. In 2025, the OECD published the OECD Public Integrity Indicators: Ecuador Country Fact Sheet,which was largely based on data collected from Ecuadorian stakeholders in 2023 (OECD 2025: 2).

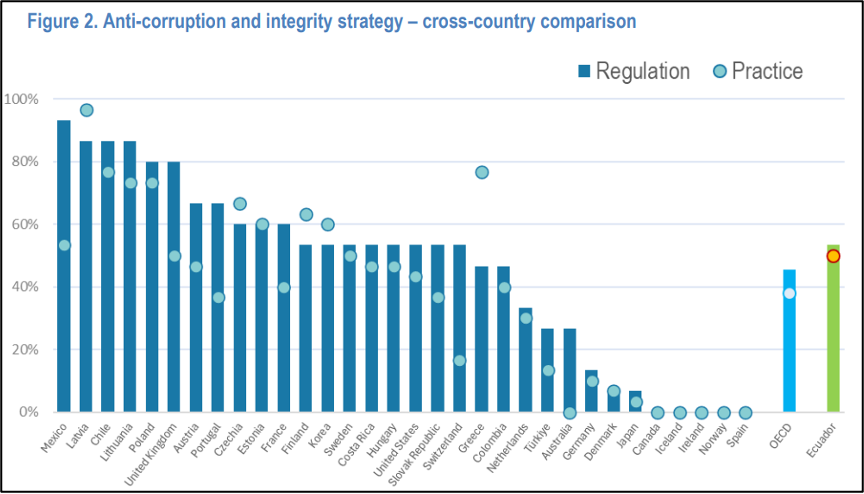

One of the most relevant indicators pertains to the quality of the country’s anti-corruption and integrity strategy, which is broken further down into scores for regulation and practices. Reviewing the 2022 national anti-corruption strategy, the OECD found Ecuador fulfils 53% of regulatory criteria on the quality of the strategic framework and 50% of criteria on the practice of the strategy, compared to the OECD averages of 46% and 38% respectively (OECD 2025: 5).a1b055105d26

Figure 6: a cross-country comparison of the OECD’s anti-corruption and integrity strategy indicator

Source: OECD 2025

It highlighted also positive elements of the strategy: the wide coverage of its eight strategic objectives (also reflected in the PNIP) and its implementation structure centred around the secretariat for public integrity, which the OECD said had the potential to improve coordination and the sustainability of the strategy’s implementation. However, it noted shortcomings in the lack of public access to information on the strategy’s implementation as well as the lack of a clear financial plan for the strategy, which could in turn undermine sustainability (OECD 2025: 6).

Other third-party assessments

Aspects of Ecuador’s anti-corruption framework, especially preventive measures, have also been assessed by civil society actors. Ecuador is currently undergoing its second cycle of review under the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), which focuses on Chapter II (preventive measures) and Chapter V (asset recovery). Ecuador has completed the self-assessment for the second cycle and is awaiting a peer review by two other states parties. This peer review process was extended and is ongoing, with the cycle expected to conclude by June 2026. As of July 2025, however, the Ecuadorian government has not yet publicly released the self-assessment checklist, full country report nor the executive summary.

Nevertheless, the civil society organisation Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo (FCD), with the support of the UNCAC Civil Society Coalition, produced an independent evaluation report to align with Ecuador’s review cycle in 2021 (FCD and UNCACC 2021). The report noted that the government did not respond to a majority of requests for the provision of information and inputs into the assessment (FCD and UNCACC 2021: 6).

The report identified several strengths in Ecuador’s existing anti-corruption framework, such as the existence of a constitutional and legal framework grounding preventive policies and practices, as well as significant advances in public procurement transparency and regulation (FCD and UNCACC 2021).

However, it also highlighted some key challenges, including the then general anti-corruption secretariat’s poor coordination of preventive measures (FCD and UNCACC 2021: 10), a lack of political will (FCD and UNCACC 2021: 22) and a lack of cohesion among oversight bodies, noting the underdevelopment of the transparency and social control branch of government. It also pointed out the absence of multisectoral mechanisms for monitoring and follow-up of current public policies (FCD and UNCACC 2021: 19).

The report also assesses Ecuador’s performance in implementing and enforcing other prevention orientated measures in line with the articles under UNCAC Chapter II (see Figure 7).

The report made several recommendations for priority action – many of which overlap with those made by the OECD – including the development (with the meaningful involvement of non-state actors) of a national plan on the prevention of and measures to counter corruption, improvements in the coordination of prevention policies and actions, and the development of model codes of conduct.

Figure 7: FCD and UNCACC’s assessment of Ecuador’s performance in implementing and enforcing UNCAC Chapter II on preventive measures (Articles 5-14)

|

UNCAC articles |

Status of implementation in law |

Status of implementation and enforcement in practice |

|

Art. 5 - Preventive anti-corruption policies and practices |

Partially implemented |

Poor |

|

Art. 6 - Preventive anti-corruption body or bodies |

Largely implemented |

Moderate |

|

Art. 7.1 - Public sector employment |

Largely implemented |

Moderate |

|

Art. 7.3 - Political financing |

Partially implemented |

Poor |

|

Arts. 7, 8 and 12 - Codes of Conduct, conflicts of interest and asset declarations |

Partially implemented |

Poor |

|

Arts. 8.4 and 13.2 - Reporting mechanism and whistleblowers protection |

Partially implemented |

Moderate |

|

Art. 9.1 - Public procurement |

Largely implemented |

Good |

|

Art. 9.2 - Management of public finances |

Largely implemented |

Good |

|

Arts. 10 and 13.1 - Access to information and participation of society |

Partially implemented |

Moderate |

|

Art. 11 - Judiciary and prosecution services |

Partially implemented |

Moderate |

|

Art. 12 - Private sector transparency |

Partially implemented |

Poor |

|

Art. 14 - Measures to prevent money-laundering |

Partially implemented |

Moderate |

Source: FGD and UNCACC 2021

There are relatively few academic assessments of Ecuador’s anti-corruption system. In one exception, Desfrancois (2022) describes the evolution of this system from 2008 and 2022, noting similar challenges such as obstacles to coordination and the overlapping mandates of various bodies.

Other practices from Latin America

This section provides an overview of select approaches undertaken by other Latin American states to prevent and manage corruption risks in their respective public administrations. It primarily relies on examples identified or recommendations made in OECD reports of other countries in the region.

Given the key challenges consistently identified in Ecuador, these ‘best practices’ are grouped around three subsections: improving coordination, ensuring continuity and enhancing risk management.

However, it should be noted that building an effective anti-corruption framework is often a heavily context-dependent undertaking; the OECD recommendation on public integrity recognises that (OECD 2017):

‘[N]ational practices on promoting integrity vary widely across countries due to the specific nature of public integrity risks and their distinct legal, institutional and cultural contexts.’

Improving coordination

As discussed above, Ecuador has consistently faced coordination challenges in implementing planned anti-corruption interventions; while evidence is inconclusive, it is likely these may also affect corruption risk management practices as led by public administration bodies.

Ecuador continues to have more than one coordination body for these purposes. While the FTCS coordination committee and the general secretariat of public integrity do not perform the same role – and also have distinct institutional grounding in different branches of the state – the plans set out under the PNIP and PNIPLCC suggest there may be overlap in some of their responsibilities – including in the management of corruption risks - thus affirming the continued need for stronger coordination.

Latin American countries like Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Peru have developed national integrity systems that bring together institutions across all state branches. These systems promote formal and informal cooperation among government institutions, create multistakeholder coordination bodies that often include the judiciary, legislative branches and civil society actors, as well as enable coherent implementation and monitoring of public integrity policies across sectors and levels of government (OECD 2021a). An overview of different public integrity systems across Latin America drawn up in 2022 illustrates the regular practice of having one coordination unit, accompanied by fixed coordination mechanisms; furthermore, many integrate a significant role for civil society, the private sector and other actors into their system (see Figure 8) (OECD 2022b).

Figure 8: OECD’s overview of public integrity systems in Latin America (as of 2022)

| Country | Co-ordination Unit | Co-ordination mechanism | Includes legislative | Includes judiciary | Includes other actors |

| Argentina | Secretary of Institutional Strengthening (Secretaría de Fortalecimiento Institucional) in the Executive Office of the Cabinet of Ministers | Informal co-ordination through working groups System is in the process of being reformed | No | No | No |

| Brazil | Office of the Comptroller General of the Union (Controladoria-Geral da União, CGU) | Anti-corruption Inter-ministerial Committee (Comitê Interministerial de Combate à Corrupção, CICC) | No | Yes | No |

| Colombia | Transparency Secretariat (Secretaría de Transparencia, ST) | National Moralisation Commission (Comisión Nacional de Moralización, CNM) | Yes | Yes | National Citizens' Committee for the Fight against Corruption (Comité Nacional Ciudadano para la Lucha contra la Corrupción) |

| Chile | Ministry of the General Secretariat of the Presidency (Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia) | Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency (Comisión para la Integridad Pública y Transparencia) | No | No | An anti-corruption alliance was established as a working group with the private sector and civil society, but they do not participate in the co-ordination structure. |

| Costa Rica | n.a. | Informal co-ordination, agreements between institutions | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Ecuador | Anti-corruption Secretariat (Secretaría Anticorrupción) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Mexico | Executive Secretary of the National Anti-corruption System (Secretaría Ejecutiva del Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción, SESNA) | Comité Coordinador del Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción | No | Yes | Citizen Participation Committee (Comité de Participación Ciudadana) |

| Peru | Secretariat of Public Integrity (Secretaría de Integridad Pública, SIP) | High-level Commission against Corruption (Comisión de Alto Nivel Anticorrupción, CAN) | Yes | Yes | Includes private sector, unions, universities, media and religious institutions (with voice, without vote) |

Source: OECD 2022b: 22

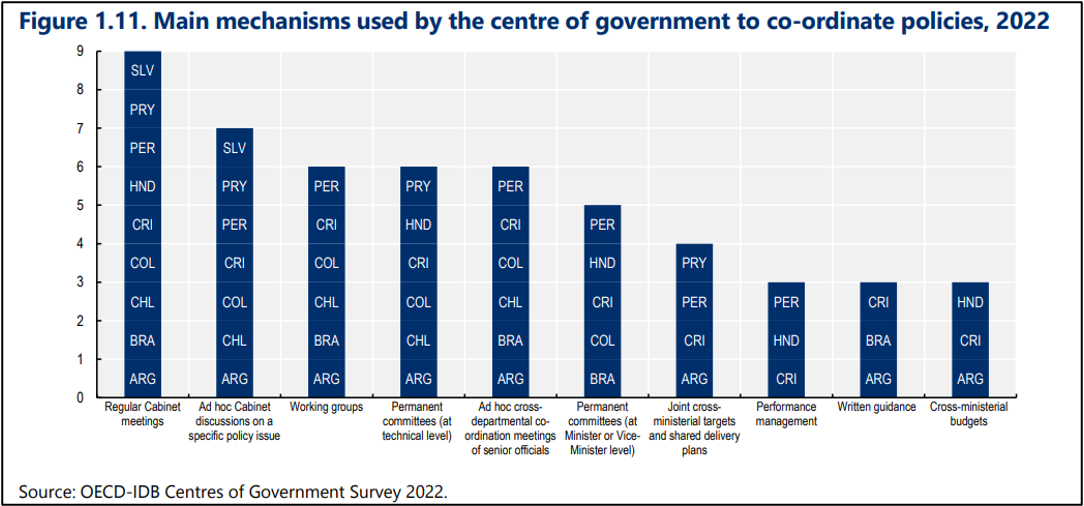

In its report on Colombia, the OECD (2017c:26) highlighted that, as in most countries, mandates and functions for preventing, detecting and sanctioning corruption in Colombia were distributed across multiple institutions. It described how Colombia overcame this challenge by establishing a national moralisation commission (CNM), which brought together all the significant anti-corruption stakeholders into a coordinating unit, although noted that the commission continued to face some coordination challenges in implementation. Another OECD survey (OECD 2024b) found that systems across Latin American countries use a variety of mechanisms to coordinate cross-sectoral governance related policies (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Overview from OECD survey of select Latin American countries on the main mechanisms used to coordinate policies as of 2022

Source: OECD 2024b: 26

According to the OECD, it is:

‘[E]ssential to create spaces for dialogue, reflection and cooperation between the branches and autonomous bodies which, while respecting their autonomy, enable taking advantage of common efforts to implement coherent public integrity agendas in all public domains, with a view to increasing its credibility and trusts’ (OECD 2024a: 30).

Argentina enhanced ministerial coordination for integrated internal controls and risk management, as well as addressing fragmentation by harmonising ethics codes and conflict of interest procedures across branches (OECD 2019a). The Organization of Latin American and Caribbean Supreme Audit Institutions (OLACEFS) describes how in some Latin American countries, coordination occurs between supreme audit institutions and public entities, to ensure the internal control measures they take align with those pertaining to risk management (OLACEFS 2021: 53-58).

In addition to having a centralised coordination unit and fixed mechanisms, another good practice on coordination emerging from the region is embedding integrity units and coordinators into different public administration entities. For example, in Peru, each federal entity is mandated to establish an integrity management unit internally. These units undertake integrity risk management, the development of the entity’s integrity plan, as well as ensure smooth communication with the country’s centralised coordination body (OECD 2022c: 15). For Ecuador, the planned establishment of IUIs or institutional integrity officers in the human talent units of public administration entities as per the PNIPLCC may signal a movement in a similar direction. Peru has also adopted peer-learning workshops to improve coordination on anti-corruption responses more generally with different institutional actors, especially sub-national government bodies (OECD 2021b).

Ensuring continuity

Ensuring the continuity of anti-corruption initiatives has also repeatedly been cited as a challenge in Ecuador, often attributed to recent political volatility. The OECD (2021c: 31) recognises this as a wider challenge, and that in practice, even where initiatives generate attention and enthusiasm when launched for the first time, this tends to gradually decrease.

In this regard, the adoption of long-term strategies with clear action plans can improve the chances for greater continuity. The OECD (2024a) encouraged Ecuador to design a state policy for integrity and anti-corruption to ensure continuity beyond election cycles, citing positive examples it identified from Mexico and Colombia. This involves co-creation of strategies with civil society and private sector input, sequencing strategy development through actionable, measurable action plans, and using indicators, baselines and evaluation mechanisms for monitoring.

In its report on Costa Rica, the OECD commended the adoption of the national strategy of integrity and prevention of corruption 2021-2030 (ENIPC), praising its ‘long-term vision until 2030 [that] allows an incremental approach in implementing the objectives and to ensure continuity, which is particularly needed in the area of integrity policies’(OECD 2022b: 26). The OECD (2022b: 26) also highlighted Costa Rican authorities’ commitments to adopt action plans through an open and participative process, and to establish a follow-up monitoring mechanism based on indicators, as efforts that could make the strategy more sustainable.

The OECD (2022a: 9) recommends that integrity initiatives are accompanied by appropriate staffing and financial resources to signal political will. In this vein, another good practice for ensuring continuity is the hiring and integration of technical experts to support the implementation of anti-corruption initiatives, continuing in their roles even in the event of a political turnover. The OECD (2022b: 26) recommended that Costa Rica consider establishing two technical sub-commissions – one on prevention and one on enforcement – to support the implementation of the ENIPC. It argued this could ‘contribute to strengthen continuity beyond changes in government and of the heads of the respective members of the high-level commission’ (OECD 2022b: 26).

The OECD also recommends that the hiring of dedicated personnel in each entity can help anchor the integrity system across the wider public administration (OECD 2021c: 31). In this vein, the example of the integrity management units in Peru is again cited as having laid the foundations for institutionalising integrity in the public sector (OECD 2024c: 44). The model adopted for the integrity management units in Peru sets out several safeguards for the role, including ensuring that the head of each unit has a senior position in the entity’s organisational structure, that they enjoy independence and are sufficiently financially resourced (OECD 2021c: 35).

In order to support Mexico’s efforts to design a corruption risk assessment and management guide, UNDP (2020) surveyed and collected best practices, identifying two examples from the region: Colombia and Paraguay. In the case of Colombia, it found the guide for corruption risk management was sustainable because its clarity, adaptability and lack of excessive budgetary implications had led to wide take up by Colombian public entities (UNDP 2020: 66). UNDP (2020: 74) found that Paraguay’s guide received legitimacy and buy-in from executive branch entities after they received tailored trainings provided by the national anti-corruption body. While each entity was responsible for allocating its own resources towards implementing the guide, the secretariat had offered training to ensure operational costs could be kept to a minimum, which UNDP (2020: 74) concluded helped financial sustainability.

Enhancing risk management

As discussed above, Ecuador has adopted corruption risk management processes in its public administration, and under the PNIP and PNIPLCC it intends to scale this up. Available evidence suggests these processes are largely aligned with international standards, although consistent implementation by public administration entities can be challenging and that data collection methods can be unclear.

In its reports on Latin American countries, the OECD has in several instances issued recommendations on how states can enhance their existing risk management processes.

In an example from Brazil, integrity risk management became mandatory for all public entities in 2017, and the office of the comptroller general of the union (CGU – O Gabinete do Ministro da Controladoria-Geral da União) has distributed practical guides to support federal entities in their implementation (OECD 2022c). However, in its consultations, the OECD identified that implementation by these entities was often inconsistent, responsible actors found the processes overly complex and that the full range of risks were often not adequately identified. In response, the OECD (2022c) recommended Brazilian authorities enhance the risk management model by adapting the guidance given to federal entities in a way that applied behavioural insights. This would help public managers responsible for implementation to become more aware of cognitive biases in judgement and to improve their ability to better understand, identify and assess integrity risks. It also recommended that Brazil undertake enhanced capacity building and training of these managers, including through the use of technological tools.

The report also recommended that Brazil make greater use of the data collected through its existing analytical tools on integrity and corruption cases to develop solutions that support integrity risk management in federal entities based on predictive models (OECD 2022c). The OECD has made similar recommendations in its report for Mexico, noting that the state had made a lot of progress in terms of collecting data and information through, for example, budget-related data sourced from different executive bodies. It noted that this data could be used more systematically for preventive purposes, for example, towards cross-sectoral mapping to identify the sectors and public administration entities at highest risk of corruption and to support such entities in their internal management of such risks (OECD 2021c: 108-109).

- For more details on this constitutional clause, known as muerte cruzada or ‘mutual death’, see Prieto, G. 2023. Ecuador’s Mutual Death Clause.

- For an overview of the WGI indicators, see page 13 of Maslen, C. 2022. How-to Guide for Corruption Assessment Tools (3rd edition).

- Percentile rank indicates the country's rank among all countries covered by the aggregate indicator, with 0 corresponding to lowest rank, and 100 to highest rank.

- Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo (FCD) is the national chapter of Transparency International in Ecuador.

- The so-called Metastásis and Purga cases concerned alleged corruption schemes involving drug traffickers and criminal justice actors. For more detail, see Voss, G. 2024. Metastasis Case Exposes Ecuador’s Corruption Cancer; Carillo, L. 2024. Ecuador Arrests Judges, Lawyers and Police Officers for Helping Criminals.

- The so-called Encuentro case concerned an alleged corruption scheme in the electricity sector. For more detail, see Ecuador Times. 2023. Electrical Sector, the ‘Meeting’ Point of the Corruption of Three Governments.

- This is discussed in further detail on page 19 of this Helpdesk Answer.

- These are: the Superintendent of Companies, Securities and Insurance; the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control; Superintendent of Popular and Solidarity Economy; Superintendent of Banks; the Superintendent of Banks; the Ombudsman of Ecuador; office of the comptroller general; the Superintendent of Economic Competition; the Superintendent of Territorial Planning, Land Use and Management; and the Superintendent of Data Protection.

- An overview of the report’s findings is given in the Overview of Assessments of Ecuador’s System section below.

- The second pillar on transparency and accountability contains several actions to establish mechanisms that enable evaluation and oversight of public management. The third pillar on citizen participation and the promotion of a culture of integrity focuses on social oversight and ethics education in preventing corruption (FTCS 2024: 11).

- The PNIPLCC envisions the creation of a national integrity system that would link the various institutions responsible for ensuring transparency and ethics in public administration (FTCS 2024: 70-71).

- The PNIPLCC envisions that each public entity will either have an IUI or institutional integrity officers in ‘human talent units’ to ensure that integrity related actions are properly coordinated and that risks associated with corruption are addressed proactively (FTCS 2024: 70-1).

- These were: oil (contracts, production, marketing, transportation), electrical power, telecommunications, public works, social security (institutions and services), health, public procurement, financing (national and international), drug trafficking, executed budgets, foreign investment (public/private partnerships), local governments (Presidencia de la República 2024: 60).

- As explained above, this entity was later replaced by the general secretariat of public integrity, established in 2024.

- The OECD (2024: 18-19) describes that in response to a 2021 recommendation, Ecuador set up an inter-institutional co-ordination body which brought together representatives of all relevant public sector institutions from all five state functions. However, the body only reportedly met twice in 2022, before being temporarily suspended. While the OECD recommended restoring and strengthening the body, this desk review was unable to locate evidence the body is active.

- Under the indicators, ‘regulatory criteria’ largely concern the strategy document and its coverage, whereas practice focuses on the actors and steps taken to implement that strategy. For a more detailed breakdown of the indictors and how they are measured, see OECD 2025: 13-17.