Could support to ACA networks be more effective than to individual agencies?

The spread of specialised anti-corruption authorities (ACAs) over the last 30 years has led to the establishment of their own international and regional networks, in particular between 2000 and 2015. But no comparative analysis exists to shed light on the purpose, activities, achievements, and challenges of these networks.

When U4 started to study the networks in 2015, we identified seven regional and one international network whose membership was limited to specialised anti-corruption bodies. (We thus made a distinction between the ACA networks and broader, multi-stakeholder anti-corruption alliances.) We later added four networks, two that had a slightly different membership and were donor-facilitated, and two that were established in 2018.

Examining the 12 networks, our study sought to answer two questions: What is the purpose of the existing ACA networks, and are they achieving what they set out to do? We hoped the findings would suggest whether it might be more effective for development partners to support anti-corruption agencies through these networks rather than, or in addition to, supporting individual agencies, whose ‘return on investment’ has often been below expectations.c3a308a1302b

Could the mismatch between expectations and the ACAs’ actual performance, within the constraints of their independence, authority, and resources, perhaps be more effectively addressed at regional and international level? All the information we could gather points towards the conclusion that unless a donor or overarching international organisation provides considerable support, or the chair of the network pursues effective membership fee collection, the networks are unlikely to be sustainable. The networks’ ambitions, of course, go beyond mere sustainability.

Networks of longer-established accountability institutions, such as supreme audit institutions and national human rights institutions, provide examples of the potential benefits of international networking and standard setting.24d7b586af5c Studying their organisation, operations, and support may help point the way towards greater sustainability and effectiveness for ACA networks.

Following the example of other accountability institutions

Supreme audit institutions have been organised for more than 60 years in the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI), which currently has 192 full members. INTOSAI considers itself an autonomous, independent, non-political, and non-governmental organisation that promotes the exchange of experiences in the governmental audit community. It has a special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (UN), and its importance was acknowledged in a resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2014, titled ‘Promoting and fostering the efficiency, accountability, effectiveness and transparency of public administration by strengthening supreme audit institutions’.

National human rights institutions have to comply with the 1993 Paris Principles if they want to be internationally accredited and have access to the UN Human Rights Council and other bodies. These principles set out minimum standards for national human rights institutions, such as a broad yet clearly defined mandate based on universal human rights standards; autonomy from government, with independence guaranteed by legislation or the country’s constitution; pluralism, including membership that broadly reflects society; adequate resources; and optional powers of investigation. A peer review system operated by a subcommittee of the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) determines the accreditation status of each national human rights institution. By May 2019, 79 of 123 institutions had been found to be in full compliance with the Paris Principles (GANHRI 2020). The diffusion of human rights standards has been centrally assessed through the United Nations and promoted through regional networks.

In the spirit of the Paris Principles, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) convened a conference together with Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission in Jakarta in 2012. The gathering, which brought together a highly experienced group of former and acting heads of anti-corruption authorities as well as representatives from some regional networks, produced the Jakarta Statement on Principles for Anti-Corruption Agencies. The Jakarta Principles have been discussed at various conferences since then, and a commentary is forthcoming. But the principles still do not have an institutional ‘home’. Some regional networks, and as of 2019 even the IAACA, have started making reference to the Principles, but there is still a long way to go before anti-corruption authorities and their networks achieve the level of institutionalisation and international clout of INTOSAI or GANHRI.

A lack of information = inactivity?

It has been difficult to obtain information from and about most of the ACA networks discussed in this brief – a principal reason why our research has stalled over four years. Unfortunately, one of the main commonalities of the ACA networks is their public invisibility and lack of up-to date web presence. One may argue that visibility is not an essential requirement for such networks, as it is the relations between network members that matter most. But the overall lack of references to the networks online, as well as at international conferences, may well be an indicator of their general inactivity. It is not surprising, then, that U4’s attempts to reach out to the networks and their coordinators often met with unresponsiveness.

The response rate to our online survey and email inquiries in 2016 and 2017 was extremely low. A questionnaire that was sent out to 10 networks, followed by an online survey for their member organisations, was answered by 24 individual respondents, some of them from the same agency. Of these, 14 were members of the European Partners against Corruption (EPAC) and the European Contact-Point Network against Corruption (EACN), which functions as a single network and was one of the most forthcoming in terms of providing first-hand information.ab34bbc85219

During the course of the research we also added two reportedly well-functioning networks that are organised by development partners and whose membership extends beyond anti-corruption authorities. The Corruption Hunter Network, facilitated by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), brings together individual investigators and prosecutors of corruption cases worldwide, regardless of whether they come from a specialised anti-corruption entity. The Arab Anti-Corruption and Integrity Network (ACINET), funded and facilitated by UNDP, also includes civil society and academic organisations among its members.

In late 2018, the Anti-Corruption Division of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Organization of American States, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Ibero-American Association of Public Ministries jointly initiated the Latin American and Caribbean Anti-Corruption Law Enforcement Network (LAC LEN). Its purpose is ‘to promote the exchange of experiences and good practices between the different jurisdictions of the region in order to equip anti-corruption law enforcement officials with the tools and knowledge necessary to effectively investigate and prosecute transnational corruption cases’. LAC LEN thus helps fill a void left by the demise of the Network of Government Institutions for Public Ethics in the Americas (2002 to ca. 2006).

At about the same time, the Council of Europe supported the establishment of a network especially for corruption prevention authorities at a conference in Šibenik, Croatia. By the time of its fourth meeting in Tunis in October 2019, the Network of Corruption Prevention Authorities (NCPA) comprised 24 anti-corruption authorities, mostly from European countries, but also from West Africa and the Middle East–North Africa region, and most recently Brazil, Canada, and Palestine.

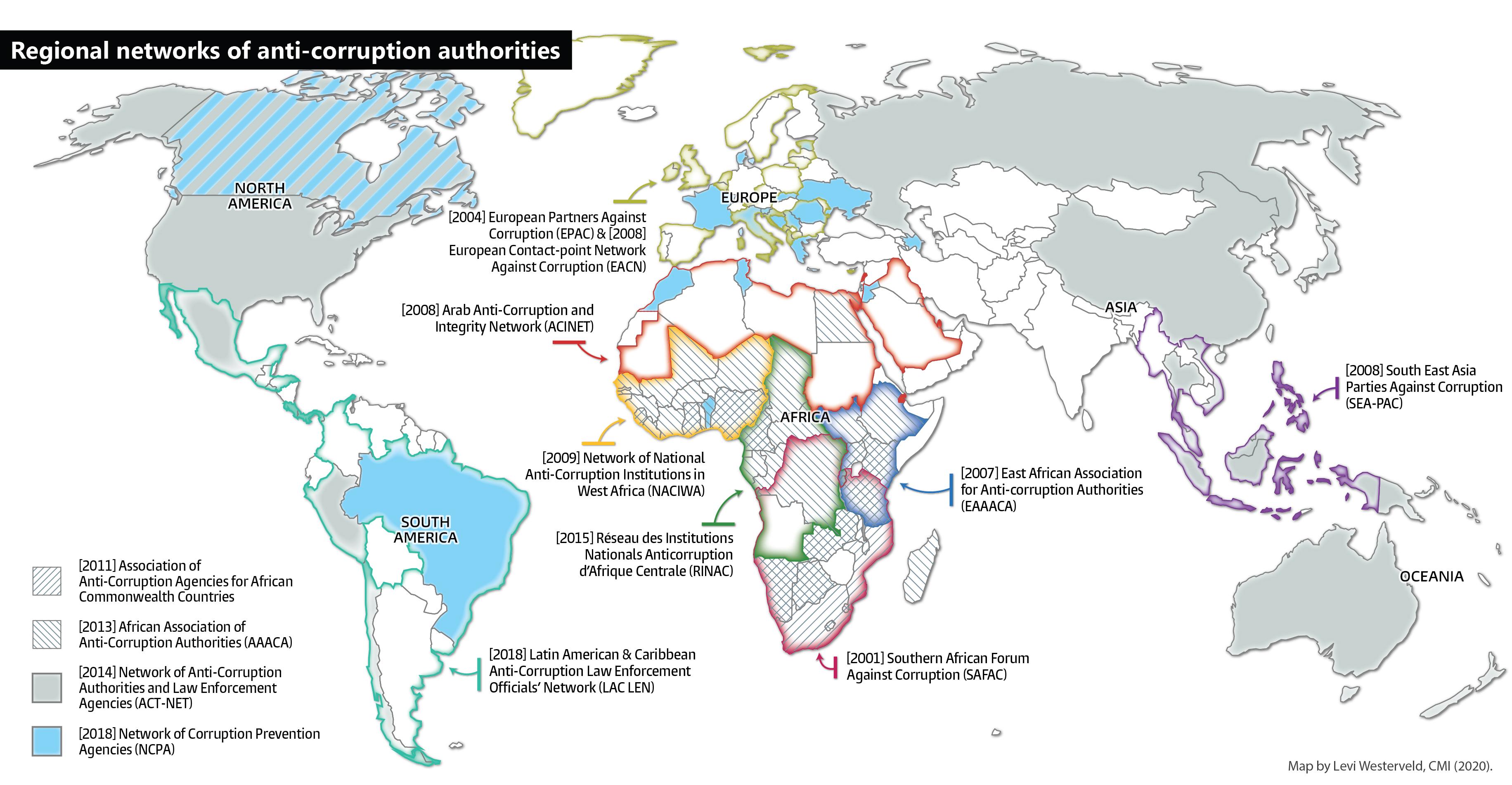

Mapping ACA networks

Africa has the highest density of ACA networks, as shown in Figure 1. Some African countries such as Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania are members of at least four networks: the Southern African Forum against Corruption (SAFAC), the African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (AAACA), the East African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (EAAACA), and the Association of Anti-Corruption Agencies in Commonwealth Africa.’

Figure 1: Regional networks of anti-corruption authorities

List of ACA networks in order of establishment

- Southern African Forum against Corruption (SAFAC), established in 2001. SAFAC is a network of anti-corruption bodies (where they exist) and representatives of governments in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). SAFAC had no functional website in January 2020 and appears to have been inactive for at least three years.

- European Partners against Corruption (EPAC) and European Contact-Point Network against Corruption (EACN). Established in 2004 and 2008, respectively, they mostly act as one network.

- Corruption Hunter Network, established by Norad in 2005.

- International Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (IAACA), established in 2006.

- East African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (EAAACA), established in 2007.

- South East Asia Parties Against Corruption (SEA-PAC), established in 2008 (initial memorandum of understanding in 2004).

- Arab Anti-Corruption and Integrity Network (ACINET), established by UNDP in 2008.

- Network of National Anti-Corruption Institutions in West Africa (NACIWA), established in 2009.

- Association of Anti-Corruption Agencies in Commonwealth Africa, established in 2011 and facilitated by the Commonwealth Secretariat. No website.

- African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (AAACA), established in 2013.

- Network of Anti-Corruption Authorities and Law Enforcement Agencies (ACT-NET) established by Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in 2014. No website.

- Réseau des Institutions Nationales Anticorruption d’Afrique Centrale (RINAC), established in 2015. The network appears to have been inactive for at least two years.

- Latin American and Caribbean Anti-Corruption Law Enforcement Officials’ Network (LAC LEN), jointly established by the Anti-Corruption Division of the OECD, the Organization of American States, Inter-American Development Bank, and Ibero-American Association of Public Ministries in late 2018. No website.

- Council of Europe’s Network of Corruption Prevention Authorities (NCPA), established in 2018.

Purpose and goals

The declared purpose and goals of the majority of networks are similar. Leading the list are capacity building, cross-border cooperation in investigations and asset recovery (through information exchange, both formal and informal), and legal harmonisation among member states. Some ACA networks (AAACA, SAFAC, and ACINET) also refer to the promotion and implementation of regional and international anti-corruption conventions.

In practice, one of the tasks that the networks have carried out most successfully, at least in terms of quantity of output, is capacity building through joint trainings, in particular for technical-level staff.

Membership

The regional ACA networks typically have between 10 and 25 member organisations each. Membership essentially depends on the number of countries in the designated region and on the existence of specialised anti-corruption bodies in these countries.

In 2016, the IAACA, an international network, had over 300 organisational members and over 2,000 individual members, including investigators, prosecutors, and anti-corruption experts. Its new website stated in early 2019 that ‘over 140 countries and regions participate in the Association through organisational and individual membership’.

The networks facilitated by Norad and UNDP are not, strictly speaking, networks of anti-corruption authorities. Norad’s Corruption Hunter Network has a core of about 20 individual members, mostly prosecutors of large corruption cases, who are selected by the development agency. Additional guests are invited on an ad hoc basis to meetings that Norad organises twice a year. ACINET includes 47 ministries and official agencies from 18 Arab countries, two observer members, and the ‘Non-Governmental Group’, which consists of 25 independent organisations from civil society, the private sector, and academia.

As shown in Figure 1, some anti-corruption authorities are members of several networks, but no two regional networks have exactly the same membership.

Organisational models and funding

In terms of their organisational structure, the networks we examined fall into two broad categories: those with chairs that rotate among network members, and those with fixed secretariats. The secretariats may be linked to either a national anti-corruption authority or a larger regional organisation or donor.

RINAC, SAFAC, and SEA-PAC have or have had rotating chairs, so that members take turns hosting annual meetings. NACIWA is closely affiliated with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), but its secretariat has rotated among its members. NACIWA went quiet for a three-year period, between 2011 and 2014, but re-emerged in March 2015 in a General Assembly meeting at ECOWAS. The cost of the venue for NACIWA meetings is borne by the respective chair, and members pay for their own travel, but in the past UNODC often covered the costs of venue, accommodation, and travel. According to NACIWA’s constitution, membership dues are US$2,000 year.

The EAAACA and AAACA have permanent secretariats in Uganda and Burundi, respectively. They are also mainly funded by member fees: US$15,000 per year for each of the EAAACA’s eight members, and US$2,500 each for the AAACA’s 33 member countries. With its membership fee and additional contributions from development partners, the EAAACA has a robust budget to fund its many activities, as detailed in the next section. The AAACA, on the other had, had a budget of just US$162,000 in 2015, not enough to run all its planned activities, even though its membership includes almost the entire African continent. Its annual general meetings have received additional support from hosting countries, UNODC, and the African Development Bank.

The IAACA is also, per its constitution, primarily financed through member fees, the rates being determined by the network’s executive committee. Its secretariat was hosted by China for a decade before it passed to the Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Centre (ROLACC) in Doha, Qatar, in 2016. Following the handover, the website became inactive, and insofar as information could be obtained, it appears there were also fewer activities. In early 2019, a new website was set up for an annual meeting hosted at the UNODC, with the draft of a revised constitution for the IAACA. It is not clear whether that new constitution was finalised and agreed upon by the end of 2019.

Still other networks have fixed secretariats attached to larger regional organisations. Examples are ACT-NET, ACINET, the Commonwealth network, and EPAC/EACN. The funding for these secretariats comes from the organisations they are affiliated with/based at, though members may contribute additional funding.

The Corruption Hunter Network is unique in that it was founded and is funded entirely by a single agency, Norad, which selects the members and invites them to events organised and paid for by the agency.

Achievements and challenges

The scant information obtainable online and the lack of responsiveness to our surveys makes an assessment of the achievements and challenges of ACA networks very difficult. The little evidence we were able to collect over the past four years does not allow us to identify a best-performing network or recommend a best practice model. However, it seems clear that those networks that have sufficient funding to afford a permanent secretariat and dedicated staff have a better chance of longevity. Ownership by members and rotation of chairs is great – until a member drops the ball and fails to convene. Once this happens, the network becomes inactive, and it can take years before another member organisation steps up to restart operations (as in the case of NACIWA).

Three networks – the Corruption Hunter Network, EPAC/EACN, and EAAACA, all established between 2004 and 2007 – were particularly responsive to our questions. We share some of their history, challenges, and achievements below. While their profiles demonstrate a variety of approaches, a common element is that all three networks have had strong institutions ensuring their sustainability.

Corruption Hunter Network: Individual moral support and technical help

Norad’s Corruption Hunter Network has consistently met twice a year for almost 15 years. Long-time members are able to quickly build trust with new members through practice-oriented discussions under Chatham House rules. Investigative journalists and select civil society organisations are also invited on an ad hoc basis, often to discuss specific cases or projects.

The coordinator of the network, asked about its main achievements to date, commented that she considers it an achievement…

…when a network participant states that ‘without the network [and] the contact and knowledge I gained through getting to know these people, we would never have been able to win this case’. Or when a previous network member says that ‘this is the only meeting I go to where people really welcome me’, or ‘if I had not had the comfort and moral support from the network, I would have had no one to talk with’.

She added:

A good number of participants have also, over the years, provided assistance to other participants without being paid (Norad cannot pay salaries), but only had their expenses covered, which again demonstrates dedication.

The author has been fortunate to be part of this network for several years. It is difficult to put a value on the moral support that participants say they receive, or to provide hard evidence of benefits attributable to the network alone, but neither should be underestimated. Hand-selected participants and a closed-door approach allow for informal peer exchange that might not be possible in a more public forum. The network thus complements more formal networks, though it cannot replace them.

At each gathering of the ‘Corruption Hunters’, Norad organises side events open to the public. An example is the panel discussion on how the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention has affected the investigation and prosecution of financial crime, organised in collaboration with U4, the University of Bergen, and the Norwegian School of Economics in May 2019. Also in collaboration with U4, the Corruption Hunters discussed and published common challenges and recommendations for managing a hostile court environment.

A short video interview about the purpose, challenges, and achievements of the network with one of its founders, Eva Joly, is available at https://vimeo.com/283914213/4a9da4a172.

EPAC and EACN: Linking the political and the technical

European Partners against Corruption (EPAC) is composed of anti-corruption authorities and police oversight bodies from Council of Europe member states. European Contact-Point Network against Corruption (EACN), a more formal network established by a European Council decision, brings together anti-corruption authorities from European Union member countries. The two networks mostly work together as one, given their shared mission and goals. Most anti-corruption authorities in Europe are also members of both. Since 2016, the EACN secretariat has been housed at the Austrian Federal Bureau of Anti-Corruption. It organises annual meetings of the 60 member bodies. The network’s board meets quarterly, and different working groups, such as those on analysis of big data or on communication tools, meet more frequently. Meetings and developments are reported in a quarterly newsletter posted on the EPAC/EACN website.

EPAC/EACN communicates through email, a website, the quarterly newsletter, phone/Skype, and the secure Europol platform for experts. A contact catalogue of all its member organisations is also available on its website. Fourteen of its members responded to our survey, and their evaluation of their membership experience was very positive throughout. Members consider the main achievements of the network to be its guidelines and its work in enabling professional relationships across borders.

EAAACA: A lapse, recovery, and branching out

The East African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (EAAACA) consists of the anti-corruption authorities of eight countries in the region. The Ugandan Inspector General of Government (IGG) initially funded the EAAACA secretariat. The Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) was a prominent EAAACA donor, providing roughly US$12 million between 2012 and 2014. Its contributions covered office rent, secretariat and staff salaries, research activities, member state personnel training, and legal/regulatory harmonisation activities. In September 2014, Sida and the EAAACA entered into a US$20 million contract, but Sida terminated the support in March 2015 due to alleged deficiencies of the EAAACA secretariat. Activities lapsed, after which the Ugandan IGG again stepped in to fund an extraordinary meeting that was held to discuss the future of the EAAACA without Sida funding. The annual membership fee for its eight members was raised to US$15,000 and now pays for the secretariat and annual meetings. In addition, development partners have supported some of the network’s work plan for 2020, which amounts to US$2 million.

The EAAACA reported a wide array of activities and outcomes in response to our questionnaire:

- Members of the East African Community spearheaded the establishment of the draft East African Community Protocol on Preventing and Combating Corruption. The Protocol has been adopted by the EAC Secretariat but is yet to be finalised as a regional anti-corruption policy.

- The EAAACA has developed the Regulations, prevention and investigation manual, which outlines diverse strategies that members are applying to fight corruption under different political, legal, and social regimes.

- A comparative analysis was undertaken to assess what each country has done towards implementing the requirements of the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption.

- Several regional training programmes have been conducted. These reportedly improved members’ skills in asset recovery, crime detection and investigations, and whistle-blower and witness protection, among other areas.

Additionally, the Asset Recovery Inter-Agency Network for Eastern Africa (ARIN-EA) has been set up to facilitate the exchange of information on individuals, companies, and assets for the purpose of recovering proceeds of illicit activities. ARIN-EA is hosted by EAAACA’s secretariat, although its presidency rotates. Each of its eight member countries has appointed three focal points that the network can contact for information and assistance requests. Direct contact with the focal points is then established through a secure platform. By the end of 2019 ARIN-EA had recorded 30 requests from within the region and internationally (as it also collaborates with other regional asset recovery networks). German International Cooperation, the European Union and UNODC support its activities.

The EAAACA has become an example of a regional association with seemingly strong ownership by its members and a practical regional outlook. It has reportedly started not only to facilitate learning but also to benchmark members’ progress in asset recovery and online declaration systems.

Going beyond annual meetings and statements

The most stable networks appear to be those that are closely linked to and/or funded by a larger regional or international organisation, such as the United Nations, the African Union (for AAACA), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (for SEA-PAC), the Commonwealth, or the Council of Europe (for EPAC/EACN and NCPA). Such organisational backing provides a normative-political framework that favours stability. However, it can also foster inertia and a formality that leaves little space for peer-to-peer exchange. Where peer learning and practical collaboration are the objective, the importance of building trust through face-to-face meetings and trainings held on a regular basis cannot be overstated. As the example of EPAC/EACN demonstrates, annual meetings and shared principles, on one hand, and informal exchanges in working groups and via closed platforms, on the other, are not mutually exclusive.

There is much to be learned from other networks and associations of accountability institutions, such as INTOSAI and GANHRI. Based on their example and on the limited information we compiled about the ACA networks to date, the following concluding points and recommendations seem in order:

- The combination of diversified resource mobilisation, with a strong base in membership fees, and a permanent secretariat appears to be a necessary condition for an ACA network’s longevity, if not effectiveness.

- A secretariat seems even more important when joint capacity building is the goal. Peer learning requires consistent facilitation over time. When regional networks struggle, the global IAACA could offer support, once it has consolidated itself again.

- Networks should conduct regular internal evaluations, perhaps following annual meetings. How useful is the network for the members? What can be improved? These evaluations could be in form of debriefing sessions or anonymous questionnaires. Ideally there should also be follow-up with members who failed to participate in meetings or other network activities, to learn their reasons for non-participation.

- The Jakarta Statement and its commentary, which has potential to be an integrating force among anti-corruption agencies, remains underused. It would seem natural for a reawakened IAACA to take this up and institutionalise it further, following the example of other accountability institutions whose global organisation, standardisation, accreditation, and peer review have helped strengthen their members’ independence and performance.

We have done our best to collect comprehensive and correct information about the networks, and we welcome to be informed about any needed corrections or updates. Please contact sofie.schuette@cmi.no.

- Johnsøn, Taxell, and Zaum 2012; Doig, Watt, and Williams 2005; Recanatini 2011; De Sousa 2010.

- De Jaegere 2011.

- Informative responses were received only from EPAC/EACN, South East Asia Parties Against Corruption (SEA-PAC), East African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (EAAACA), Norad’s Corruption Hunter Network, Association of Anti-Corruption Agencies in Commonwealth Africa, and African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (AAACA).