Query

Please provide an overview of recent developments with regards to corruption and anti-corruption in Moldova, with a focus on state capture and the prospects for reform.

Overview of corruption in Moldova

Background and recent political developments

Moldova emerged as an independent parliamentary republic following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 (The World Bank 2017; BBC News 2017). Russian forces, however, remain on Moldovan territory, east of the Nistru River, supporting the breakaway region of Transnistria, which is mostly inhabited by Ukrainians and Russians but also has a sizeable ethnic Moldovan minority (CIA 2022).

Moldova is still one of the poorest countries in Europe, with recent economic growth largely reliant on “remittance-induced consumption” (World Bank 2021, para 1). The ageing and shrinking population in combination with a decline in remittances has also led to a low growth in productivity and a dependence of much of the population on social assistance and pensions. A drought in 2020 and the impact of Covid have further shown how vulnerable the economy is to shocks. However, the new government has started to work on more inclusive and resilient growth models and has looked to regain trust among international partners and citizens (World Bank 2021).

Years of Communist Party rule in the post-independence period ended with violent protests and a rerun of parliamentary elections in 2009 (CIA 2017). Between 2010 and 2019, Moldova was ruled by a series of pro-Europe coalitions, but in 2016, Igor Dodon, a pro-Russian candidate won the presidency, backed by the oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc, head of the nominally pro-European Democratic party and the richest man in Moldova (Hajdari 2019). The two politicians “created a particular system of government that resemble[d] a political cartel” (BTI 2020: 3). Subsequently, in 2019 Dodon’s PSRM party won the largest share of the vote in the parliamentary elections.

Following these elections, PSRM entered into a coalition government with the pro-European coalition ACUM, with the ACUM's Maia Sandu inaugurated as prime minister. Despite the apparent juxtaposition between the pro-Russian leanings of the PSRM and the pro-European agenda of ACUM, Longhurst (2021: 71) notes that both parties were united in their determination to oust “the oligarchic regime created by the Democratic Party of Moldova (PDM) under the stewardship of oligarch in chief Vladimir Plahotniuc”.

After surviving an immediate constitutional crisis in June 2019 during which, the constitutional court first voided and latter validated her appointment as prime minister (Constitutional Court of Moldova 2019), Sandu lost a vote of no confidence in November 2019 when PSRM withdrew its support (Deutsche Welle 2019).

A year later in November 2020, Sandu stood as a candidate in the presidential elections, in which she ultimately defeated Dodon by a margin of 57.75% to 42.25% in the second round (Deutsche Welle 2020). While the election was positively evaluated by the OSCE/ODIHR Election Observer Mission, the election campaign was “characterised as negative and divisive, involving personal attacks and polarising, intolerant rhetoric”(European Commission and HR/VP. 2021: p.3). In addition, the mission voiced concerns over vote buying and organised transportation of voters on the day of the election and, similarly to earlier years, lack of campaign funding oversight” (European Commission and HR/VP 2021: 3).

Despite her victory, President Sandu was faced with the prospect of working with a legislature in which Dodon and his allies controlled 54 of a total of 101 seats (Reuters 2021). After repeated attempts to form a workable government failed in early 2021, a constitutional tussle over whether circumstances justified the dissolution of parliament were met ensued (Balkan Insight 2021). This was criticised at the international level, including by the US State Department, which released a press statement that called the PSRM-dominated parliament’s attempt to replace the president of the constitutional court in April “a blatant attack on Moldova’s democracy” (USDS 2021). Finally, snap elections were held in July 2021.

The result was another clear victory for Sandu’s Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), which swept up 63 of the 101 seats in parliament, providing the government with a clear pro-European mandate (Leontiev 2021).

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. After reviewing recent trends with regards to the incidence of corruption in Moldova, the following section considers the prospects for reform in the wake of the 2021 parliamentary elections and the consolidation of PAS’s political authority.

Then, the paper focuses on systematic corruption challenges in the country, most notably state capture and judicial corruption.

Finally, the paper takes stock of anti-corruption progress that has been made over the last decade or so to address these entrenched issues.

Extent of corruption

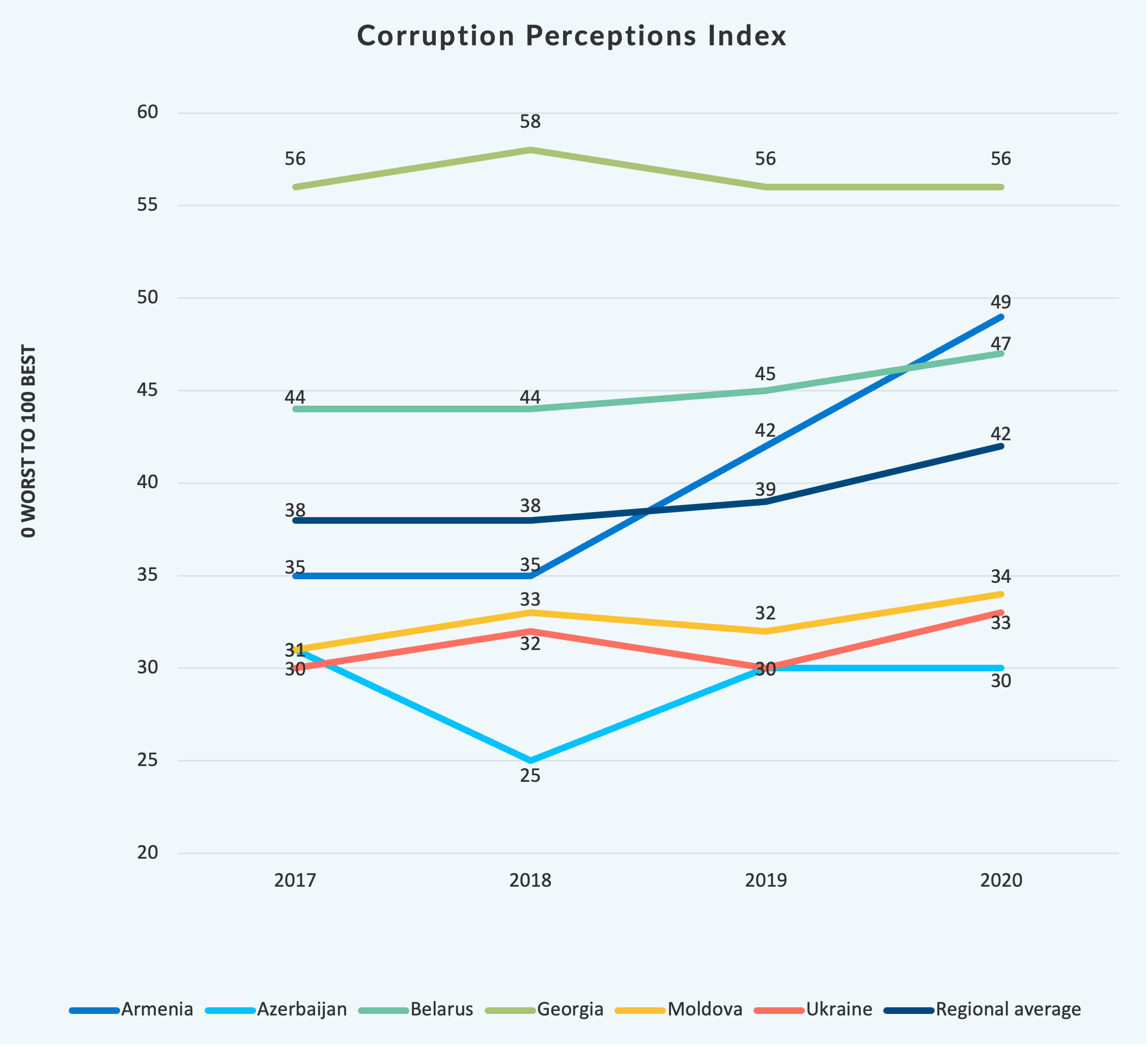

Transparency International ranked Moldova at 115, alongside the Philippines in the 2020 Corruption Perception Index (CPI). With 34 out of 100 points there has been a small improvement of 5 ranks and 2 points since 2019. Countries with a low CPI score are said to be plagued by “untrustworthy and badly functioning public institutions” where anti-corruption laws exist only in name and people are frequently confronted with bribery and extortion (Transparency International 2017; Vlas 2017).

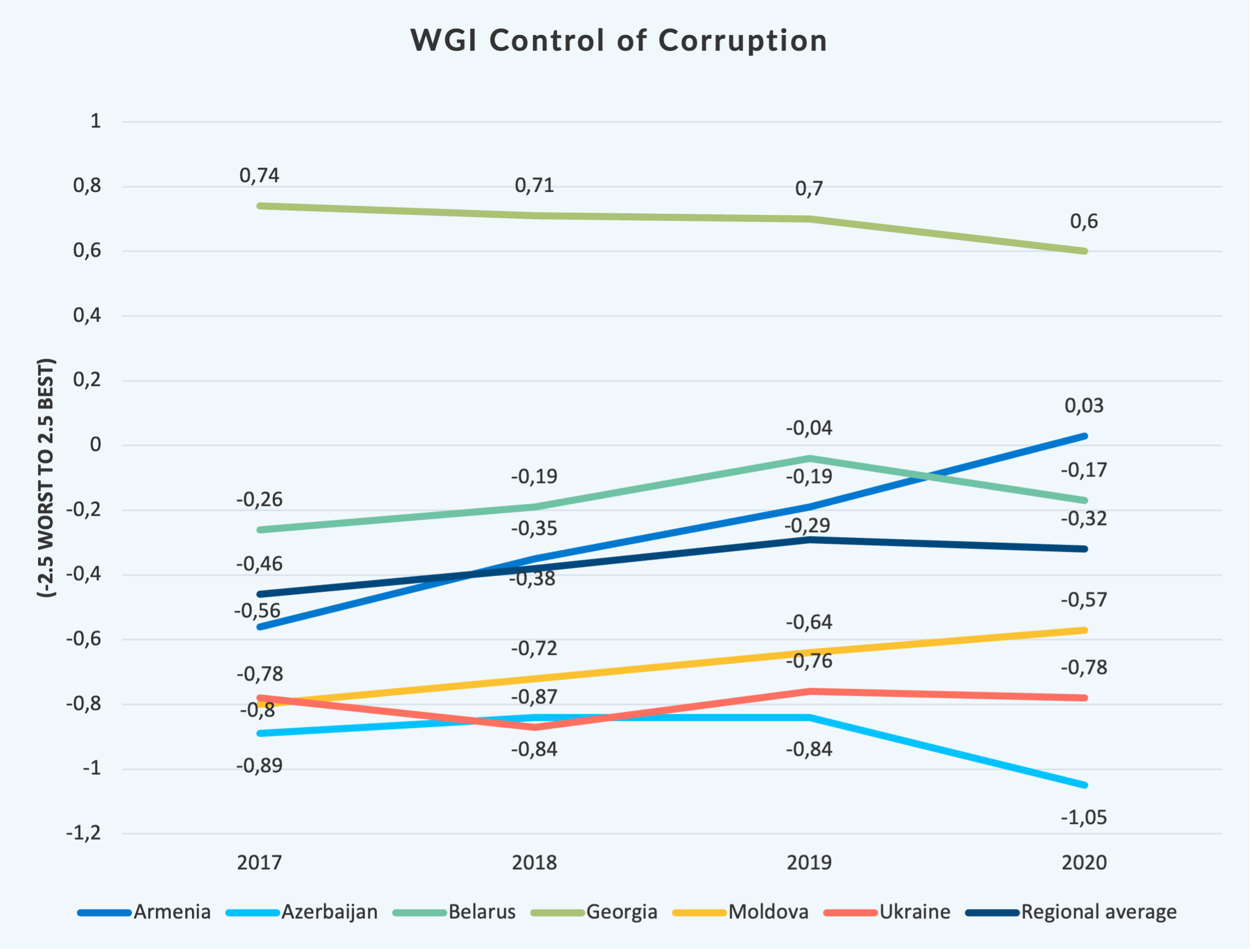

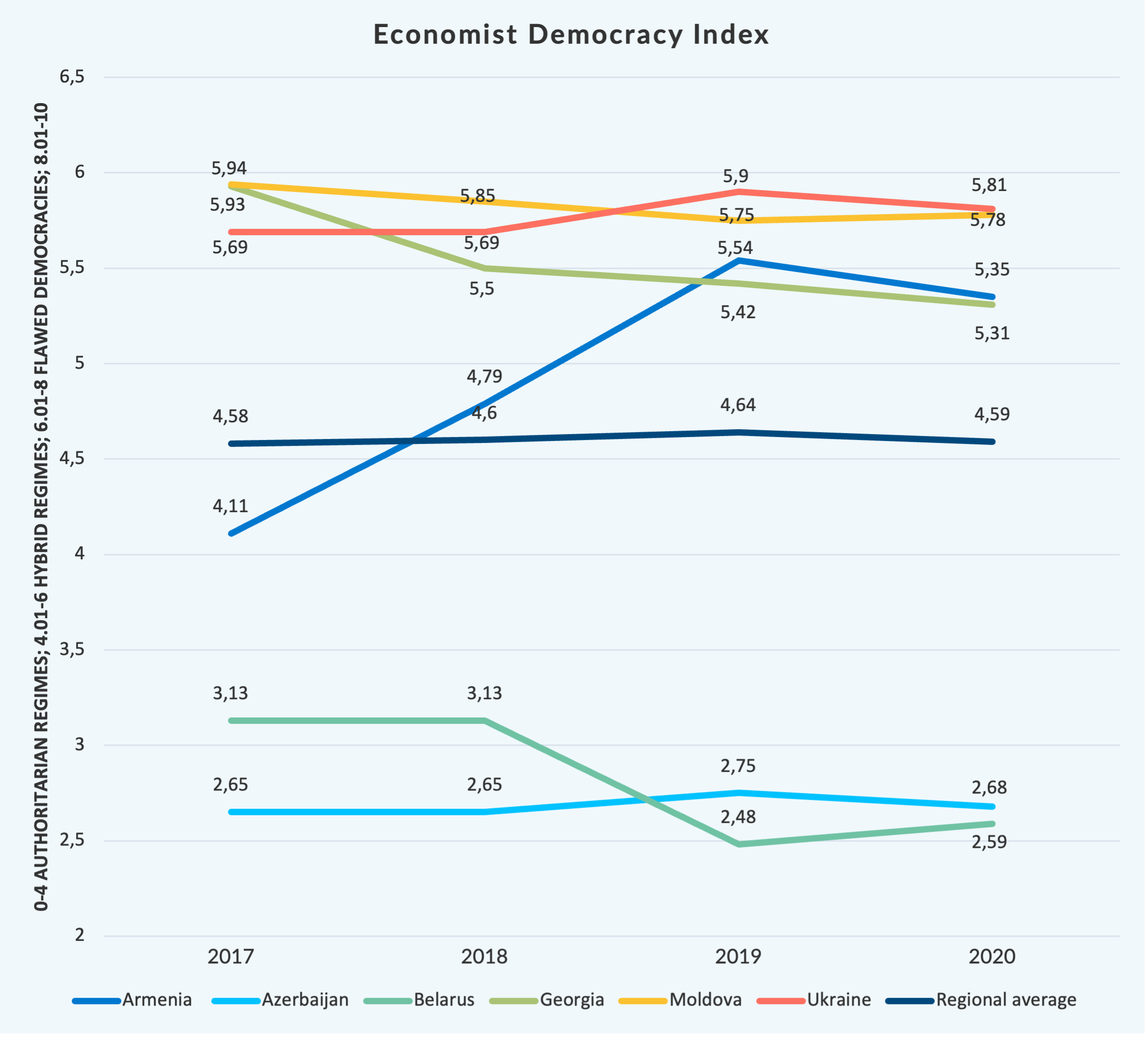

Overall, since 2017 the governance indicators have remained relatively stable. Table 1 gives an overview of the different available indicators from 2017–2021.

For a complete set of graphs comparing Moldova to other Eastern Partnership countries on the indices included in Table 1, see the annex.

Table: 1: governance indicators Moldova 2017-2021

|

Control of corruption |

Corruption Perceptions Index score |

The Economist Democracy Index |

Rule of Law Index score |

Press Freedom Index (rank) |

Freedom House Democracy Score |

UNCAC Status |

||

|

Score |

Percentile Rank |

|||||||

|

2017 |

-0.80 |

21.15 |

31 |

5.94 |

0.49 |

80/180 |

35 |

Ratified (2007) |

|

2018 |

-0.72 |

25.96 |

33 |

5.85 |

81/180 |

35 |

||

|

2019 |

-0.64 |

28.85 |

32 |

5.75 |

0.49 |

91/180 |

34 |

|

|

2020 |

-0.57 |

30.29 |

34 |

5.78 |

0.50 |

91/180 |

35 |

|

|

2021 |

0.51 |

89/180 |

35 |

|||||

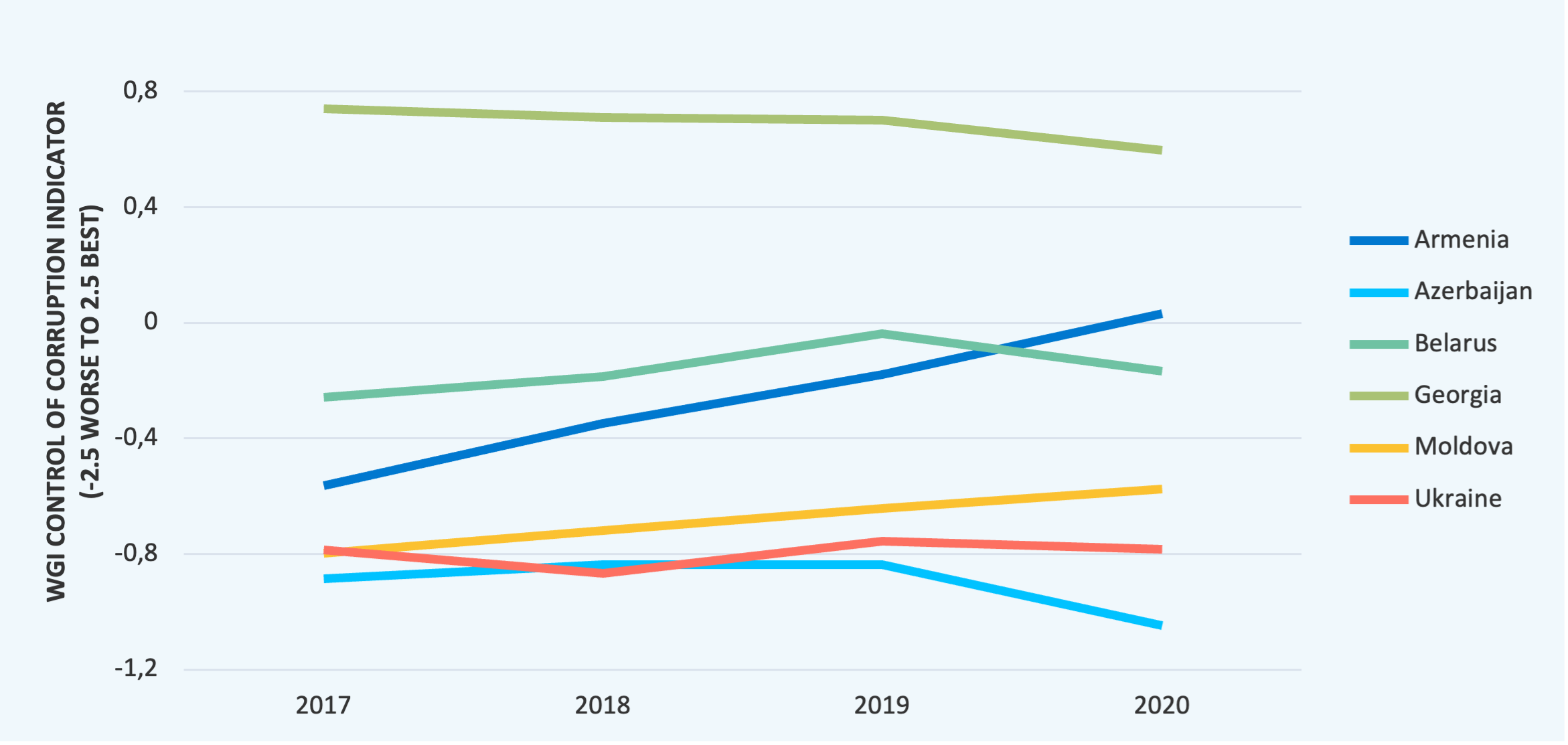

Figure: 1: WGI Control of Corruption Indicators Eastern Partnership Countries 2017–2021.

Comparing the country to the other Eastern Partnership countries, Moldova is on the lower end of the performance scale, but has witnessed some small improvements since 2017 (Figure 1).

In 2017 a study by the Expert Grup found that an estimated 8% to 23% of the annual GDP was lost to corruption and about 2% of GDP was paid in bribes. The study also highlights that this about the equivalent of all expenses for roads incurred in 2016 (Expert Grup 2017).

In the 2020 World Bank Doing Business Report Moldova is ranked 48 out of 190 countries, and the business environment is widely viewed to be compromised by corruption, lack of judicial independence and outdated regulations (European Commission and HR/VP 2021).

The National Integrity and Anti-corruption Strategy (NIAS) 2017–2020 Impact Monitoring Survey for Moldova found that there was a decrease from 25% to 19% in the share of the respondents who believe that the level of corruption in Moldova has reduced. At the same time, the number of respondents who indicated that they find any instance of corruption unacceptable grew from 53% to 57%, a trend especially evident among businesses (UNDP 2021: 11).

In 2020, only 15% of respondents believed that efforts to counter corruption are effective (compared to 18% in 2017). More encouragingly, the overall bribe incidence has decreased from 7.5% of respondents who reported giving bribes in the form of cash in 2017 to 6% in 2020 (UNDP 2021: 69). Similarly, while 4.6% of those surveyed stated they had paid bribes in the form of gifts in 2017, this figure had declined to 3.1% by 2020 (UNDP 2021: 11)

The NIAS 2017–2020 Impact Monitoring Survey for Moldova also identified a number of sectors that are especially prone to corruption, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2: areas where citizens most frequently faced demands for unofficial payments (UNDP 2021: 69).

|

Sector |

2017 |

2020 |

|

health care |

16% |

11% |

|

police |

8% |

8% |

|

border police |

7% |

10% |

|

educational establishments |

7% |

8% |

Overall, in the study from 2020, women were more likely to pay bribes than men (12% vs. 8%) (UNDP 2021: 69). The bribe rate among people with a high level of education (14%), those residing in Chisinau (13%) and people with a high level of income (17%) was higher than average, which the study explains by reference to the fact these groups interact more frequently with authorities (UNDP 2021: 67).

Table: 3: areas where businesses most frequently faced demands for unofficial payments (UNDP 2021: 69).

|

|

2017 |

2020 |

|

Agency for Intervention and Payments in Agriculture (AIPA) |

4% |

4% |

|

cadastral office |

3% |

3% |

|

public procurement agency |

NA |

3% |

The institutions that reportedly solicited bribes most frequently from businesses are displayed in Table 3, although the authors of the study emphasise the results for the businesses are not conclusive because of the small number of responses received (UNDP 2021: 69).

In light of this mixed picture, a large part of the population still seems to be unconvinced that the anti-corruption measures in the country are effective. According to the Impact Monitoring Survey, there has been a slight decrease since 2017 in respondents stating that the current measures to counter corruption are effective, where 1% (2% in 2017) state that the measures are very effective and 12% (versus 13% in 2017) find them fairly effective. Meanwhile, 35% of respondents in 2020 found them absolutely ineffective (29% in 2017). In addition, while the overall indicators reflecting how many respondents reported corruption grew from 9% in 2017 to 14% in 2021, 48% of respondents that had experienced corrupt practices and notified them reported that the behaviour was not sanctioned but they “suffered some damage”, a steep rise from 28% in 2017. The main reason for not reporting corruption was either that respondents believe that it would be useless and no measure would be taken (48% from 49% in 2017) or that there is no system to protect whistleblowers (27% from 36% in 2017) (UNDP 2021).

A 2021 study by UNICRI analysed illicit financial flows and organised crime in Moldova. The main criminal activities in Moldova are identified as being “corruption, tax evasion, illicit drug trafficking, human trafficking, tobacco smuggling and the smuggling of illicit goods” (UNICRI 2021: 14). The Moldovan banking sector and shell companies in different jurisdictions are identified as important players in these crimes. Transnistria is reportedly often involved in money laundering schemes as the financial and banking regulations there to not comply with international norms (UNICRI 2021).

Prospects for reform: the recent elections

The July 2021 elections saw the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) secure a majority in parliament. Observers have seen this as a clear step forward for the country’s pro-European and anti-corruption movement as it reflects a popular consensus that corruption is a key impediment to democratic consolidation and lends momentum to needed reforms (Leontiev 2021).

Announcements by the PAS government to the effect that they will end the “the rule of thieves” have led to cautious optimism on the part of pro-European political commenters (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2021). In addition, interviews with civil society organisations in Moldova conducted while researching this paper indicate that the entry to power of the new PAS government has reversed the previous trend of restricting civic space.

It appears that PAS’s rise to power has at least partly disrupted kleptocratic figures, and key financial institutions are now run by new figures, while investigations into corruption and other misbehaviour are ongoing (Transparency International Moldova 2020a).

Despite these encouraging signs, there have also been some troubling developments that point to a lack of a strategic approach when it comes to implementing anti-corruption measures and reforming the justice sector.

PAS dominance in the legislature

PAS’s control of the legislature provides a window of opportunity to push through rapid and comprehensive anti-corruption reform. However, there is some cause for concern that without adequate checks and balances, the new figures in government could resort to established patterns and modes of governance that are problematic.

Some of the actions taken by PAS since coming to power demonstrate a zeal for rapid results but not always for adherence to formal procedures, which risks setting a dangerous precent. Notably, the new government sought to rush through complex changes to legal frameworks in early August 2021, at a time when many people were on leave.

Specifically, PAS parliamentarians introduced four legislative amendments to key pieces of legislation:

- draft law no.169/2021 amending law no.132/2016 on the National Integrity Authority and law no.133/2016 on public officials’ financial disclosure and interest declarations (Parliament of the Republic of Moldova 2021a)

- draft law no.178/2021 amending law no.1103/2002 on the National Anti-Corruption Centre (Parliament of the Republic of Moldova 2021b)

- draft law no.180/2021 amending law no.947/1996 on the Super Council of Magistracy, law no. 514/1995 on the Organisation of the Judiciary, and law no. 3/2016 on the prosecutor’s Office (Parliament of the Republic of Moldova 2021c)

- draft law no.181/2021 amending law no.3/2016 on the prosecutor’s office (Parliament of the Republic of Moldova 2021d)

The PAS-controlled parliament also left fewer than the regulation 15 days typically required for consultation, which left insufficient time for experts, CSOs and other actors to comment on the proposed legislative changes (Transparency International Moldova 2021a)

This not only precluded an opportunity for meaningful debate and consultation on the proposed changes but also directly contravened recommendations made by the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) in Moldova’s most recent evaluation. In Moldova’s second compliance report in the fourth round of evaluations, GRECO (2020: 4) had criticised the previous government’s “repeated failure to systematically ensure adequate timeframes for meaningful public consultation and parliamentary debate.”

Moreover, it appears that, rather than officially publishing draft legal changes, the amendments were initially posted on the website of the PAS political party in contravention of the law on the transparency of decision-making processes (Republic of Moldova 2008).

Beyond procedural concerns related to consultation and transparency, Transparency International Moldova also criticised the substance of some of the proposed changes. The organisation expressed concern about the changes proposed by draft law no. 169/2021, including planned changes to the composition and mandate of the Integrity Board (Transparency International Moldova 2021b).

Similarly, they noted that the proposed amendment to law no.1103/2002 would have abolished the competition procedure to appoint the director of the National Anti-Corruption Centre, in contravention of international and national standards (Transparency International Moldova 2021c).

These legislative initiatives seem to have been part of a wider effort by PAS to wrestle political control of key positions in institutions with a role to play in anti-corruption efforts. A good example is the tussle over the Prosecutor General’s Office, where the PAS administration has sought to replace Prosecutor General Stoianoglo (Necsutu 2021a).

Stoianoglo was originally appointed during the tenure of former president Dodon and is perceived to be close to him (Necsutu 2021b). As Prosecutor General, Stoianoglo dropped charges against controversial businessman Veaceslav Platon, who is alleged to have been involved in major corruption scandals including the “theft of the century” and money laundering schemes such as the Russian Laundromat (Necsutu 2018; OCCRP 2016). According to Necsutu (2021a), Stoianoglo was a former employee of Platon’s, and that his wife has companies in Ukraine linked to ones owned by Platon.

The PAS government seems to have tried to remove Stoianoglo in a variety of ways. First, efforts by the PAS government to revise the law on the prosecutor’s office seem to be at least partially about removing Stoianoglo as Prosecutor General (Venice Commission 2021a). As TI Moldova (2021d) have observed, the law of the prosecutor’s office has now been amended 19 times since 2016, “the only effect being the substitution of some persons with others in important positions” as each parliamentary majority attempts to tip the balance of power within the Superior Council of Prosecutors in its favour.

As the conflict between Stoianoglo and PAS escalated in autumn 2021, he was arrested in October by the Information and Security Service on corruption charges (Banila 2021), a move that his supporters – largely from the same breakaway region of the country that Stoianoglo hails from – claim is political motivated (RFE 2021).

While PAS spokespeople claim Stoianoglo is culpable of failing to investigate significant corruption cases (Necsutu 2021b), authorities seem to be struggling to make a clear case against him (Ernst 2021).

The politicisation of key posts thus remains a concern, and the new government has also been accused of clientelism, not least as a lawyer who previously represented President Sandu was appointed as ombudsman (ZDG 2021a) before having to resign in December in the face of criticism from civil society groups that she seemed to be offering undue advantages to a convicted pimp she had previously defended in court (ZDG 2021b; EAP-CSF 2021).

These cases speak to a wider issue as PAS seems to be trying to advance its anti-corruption agenda in an uncoordinated fashion and taking shortcuts that could well lead to court challenges. Civil society representatives interviewed for this paper stressed that, while reform is needed, it needs to be done in a strategic manner that complies with legal standards.

Relative inexperience of PAS parliamentarians

One consequence of the landslide electoral victory in July 2021 is that a new wave of new and fairly inexperienced PAS parliamentarians entered the legislature. While this means that they tend to have a clean slate that renders them more resilient to efforts to blackmail or otherwise corrupt them, according to an expert interviewed for this paper, this lack of experience also means that they are poorly equipped to hold sophisticated and engrained corrupt networks to account.

The effects of this lack of experience could be seen both in foreign and domestic policy in recent months. One of the main sources for rent for the entrenched elites has long been the energy sector where poor management and inadequate oversight has allowed corrupt individuals to line their pockets. When the new government came to power, Russia selected not to renew the gas contract that had been renewed yearly since 2007. According to Wolczuk (2021), the new contract stipulated new conditions related to “energy prices, debt settlement, a halt on energy market reforms and, it can be logically inferred, further integration with the EU”. Having lost influence and support in Moscow, the new pro-EU administration has been subject to an energy crisis that some observers view as a cynical attempt by Russia to blackmail Chisinau (Verseck 2021). Unsurprisingly, the government has chosen to take a non-confrontational course.

Domestically, PAS has appointed individuals to key bodies that seem to lack the experience to effectively rein in sophisticated corruption schemes. One example is the Parliamentary Commission Control of Public Finance, where PAS representatives appear to lack the necessary expertise on public financial management to effectively oversee the Chamber of Accounts. Meanwhile, the fugitive businessman-cum-politician Ilan Shor – heavily implicated in the Kroll audit of the “theft of the century” (Radio Free Europe 2015) – is a member of the Parliamentary Commission, and analysis by Transparency International Moldova suggests that PAS Commission members do not seem to possess sufficient skills to effectively supervise the control of public finance.

Systemic corruption challenges

State capture

State capture refers to “a situation where powerful individuals, institutions, companies or groups within or outside a country use corruption to shape a nation’s policies, legal environment and economy to benefit their own private interests” (Transparency International 2009: 43).

State capture is part of the legacy of the collapse of the Soviet Union, and “the ways in which power and ownership were appropriated in the early 1990s, which saw the rise of oligarchs and the embedding of oligarchic economies” (Longhurst 2021: 69).

Moldova is unfortunately no exception to this story. After the end of the USSR, Moldova went through a transition process of “three overlapping transformations: marketisation, democratisation, and state-building” (Marandici 2021). State capture was a result of the reform path the “post-1991 partial reform path which enabled the emergence of oligarchs able to seize core state functions and distort business environments to the detriment of the public good” (Longhurst 2021: 68).

The coalition agreement of the so-called “pro-European coalition” from 2010 to 2014 contained a secret annex agreeing that “the members of the coalition shared control over the supervisory and prosecution institutions that are supposed to be independent” (Tofilat and Negruta 2019: 9). This led to the Democratic Party of Moldova (PDM), dominated by Plahotniuc, gaining control over the National Anti-Corruption Center and the Prosecutor General’s Office At the same time, the PDM also gained control over the National Bank of Moldova (NBM).

Tofilat and Negruta (2019: 9) describe the complex web of relations that enabled political forms to capture supposedly unpartisan institutions:

“Dorin Dragutanu, the former governor of the NBM, has held several leading positions within the audit company PwC Moldova, including the position of country-manager for Moldova during 2003-2005. One of his subordinates was Andrian Candu, the Democratic Party MP and the former speaker of the Parliament. Candu is also the wedding godson of Vladimir Plahotniuc. Before his resignation in September 2015, on the eve of the arrival of an IMF mission to Moldova, Dragutanu had a secret meeting with Candu. Furthermore, Otilia Dragutanu, the wife of the former NBM governor, has recently become an MP of the Democratic Party following the 2019 parliamentary elections”

Chayes (2016) also provides a detailed analysis of the kleptocratic network around Plahotniuc, revealing a complex web of government officials (including in the judicial branch, the National Anti-Corruption Center, the central bank, and the Ministry of Economy), private sector actors (such as banks and construction contractors), as well as criminal actors, facilitators and external enablers.

These type of networks enabled a vast corruption scandal referred to as the Russian Laundromat, which was a money laundering scheme facilitated by political elites in Moldova. Investigative journalists found that billions of US dollarsc7b747a9dd03 were laundered between 2010 and 2014 through Moldovan banks from Russian banks and then transferred to shell companies with bank accounts in Western countries. Russian companies would guarantee a contract between two fake companies, where one would then file a complaint against the other for non-payment and ask the guarantor to step in. A judge in Moldova would be bribed to certify that the debt is real and order payment. The Russian company would pay and in combination with the judge’s order, the money could be moved through Moldova into banks in the West (Radu, Munteanu, and Ostanin 2015).

In their detailed analysis of the scheme, Tofilat and Negruta (2019) highlight that it could only be made possible with the help of multiple state actors, and they show that there was a severe lack of oversight in the banking sector, including the national bank, the Office for Prevention and Fight against Money Laundering (OPFML), the prosecutors office and the Superior Council of Magistracy (SCM). Concerningly, two of the former members of the SCM implicated in the case were even promoted as judges of the constitutional court in December 2018 (Tofilat and Negruta 2019: 11)

Tofilat and Negruta (2019: 8f) further contend that:

“All available evidence demonstrates that all the responsible state institutions were aware of the laundering scheme but did not take any measures to prevent it… This well-coordinated activity could not have taken place without the political protection of the ruling parties.”

The money laundering scheme was also made possible through several legislative changes that had been approved by parliament, such as capping the 3% tax for the examination of debt recovery claims in 2010 and a law that allowed courts to suspend the decisions of the OPFML to block a suspicious transaction in 2011, although the latter was revoked in 2014 (Tofilat and Negruta 2019).

Interestingly, while no one had been convicted in the Russian Laundromat case as of 2019 (Tofilat and Negruta 2019: 11), other corruption allegations served to topple a main rival of Plahotniuc, the former prime minister Filat from the Liberal Democratic Party (PLDM). In May 2015, a report was leaked that showed that the country’s top three banks had suspiciously transferred around US$1 billion (12% of the country’s GDP), which resulted in massive anti-corruption protests. The report implicated Filat and was reportedly leaked by the speaker of the parliament, Candu, a close ally of Plahotniuc (Chayes 2016).

Longhurst (2021: 75) argues that by this point the PDM, which controlled the office of prime minister 2016 to 2019, was “essentially a front to oligarchic businesses”. While the party did not have the majority in parliament, they managed to lure MPs from other parties to join their ranks who were allegedly “convinced” by the oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc through bribes and blackmailing (Transparency International Moldova 2017a; Longhurst 2021: 75). This meant that the parliament no longer represented the outcomes of the 2014 election but was essentially captured by certain business interests.

This control was consolidated through the reform of the electoral system in 2017. The ruling PDM proposed to create single member districts, a kind of first-past-the-post system in which losing parties win no representation at all.

The European Commission for Democracy through Law (also known as the Venice Commission) and OSCE/ODIHR cautioned that “in the present Moldovan context, the proposed reform could potentially have a negative effect at the constituency level, where independent majoritarian candidates may develop links with or be influenced by businesspeople or other actors who follow their own separate interests” (Venice Commission and OSCE 2017: 5)

While ultimately Plahotniuc’s attempt was not successful and a mixed system was introduced, Longhurst (2021: 76) argues that Plahotniuc was still able to rig the system to his advantage and that the reforms “represented a substantial power grab”.

Although state capture was already extensive prior to that time, until then multiple oligarchs had captured different parts of the state, which resulted in some degree of political competition (Longhurst 2021). According to Longhurst (2021: 86):

“Concentration of oligarchic power started around 2009 (at the end of Voronin’s period of autocratic rule) and crystallised in 2016 when Plahotniuc becoming [sic] the main veto player. His domestic veto power was buttressed by the international role he was able to carve for himself, especially in the United States where he was fêted as a pro-Western anti-Russian bulwark.”

Around this time, a series of laws was passed that would allow political elites to legalise money from illegal schemes, including two laws introduced in 2016: “the law of capital amnesty” and “the law of citizenship through investments” (Transparency International Moldova 2020b). The amnesty law allowed any citizen to legalise hidden assets by paying a 3% fee of the declared value of the assets, in exchange for which they would be immune from prosecution for tax evasion (Expert Grup 2018a).

The law of citizenship through investment – a so-called golden visa programme, similar to those found in Malta and Cyprus – was packaged as an initiative to support an entrepreneurial environment in the country, but according to TI Moldova (2020b), it was really aimed at generating income from international money laundering networks.

The National Anti-Corruption Center, which is tasked with assessing draft laws, reported that this law would be “detrimental to the public interest and with major risks for the safety and security of the citizens and of the state of the Republic of Moldova” (Transparency International Moldova 2020b). The law has now been suspended but was used by several “relatives and close friends of the main figures of several investigations initiated in a series of files related to bank fraud, fraudulent concessions of state assets, and persons with travel bans” (Transparency International Moldova 2020b).

State capture in the country led to serious tensions with international organisations, such as the World Bank, the IMF and the EU (Longhurst 2021). Cenuşa’s (2018) analysis shows that in 2018 the discussion around Moldova being a captured state was the focus of the European Parliament, which passed a resolution stating that the country “had become ‘state captured by oligarchic interests’ that exert their influence over most part [sic] of Moldova's society” (Jozwiak 2018: para 1).

The resolution highlighted that the space available for civil society was shrinking and that “core values are being undermined by the ruling political leaders colluding with business interests and unopposed by much of the political class and the judiciary” (Jozwiak 2018: para 2).

Events around the 2018 election of the mayor of Chisinau also led to censure by the European Union. After the former mayor had resigned due to corruption allegations, Andrei Năstase, an opposition candidate supported by Maia Sandu, won with 53% of the vote. However, he was accused of breaking the law of election silence by disseminating election material on the day of the vote, and the victory was ruled invalid (Nadu 2020). As a result, the European Commission froze the first tranche of a macro-financial aid package (Cenuşa 2018). However, this external pressure had limited effect in convincing the political elite to sever their ties with oligarchs and prioritise measures to strengthen the rule of law (Cenuşa 2019)

Measuring state capture is not a straightforward task, but by around 2018, it seems fairly clear that state capture in Moldova involved not only a few key agencies but essentially the entire state apparatus and all three branches of government (Longhurst 2021)

The media – often considered the “fourth branch” of government – was also increasingly affected by oligarchic capture as more outlets fell under the influence of political elites. The situation was not helped by the fact that the regulatory framework is outdated and does not adequately address social media or online media outlets, in addition, enforcement and compliance with the existing laws is weak and access to information is often restricted (Bologa 2021). Around this time, efforts by politicians and authorities to intimidate and harass journalists also increased (RSF 2020).

The impact of such rampant corruption is ultimately felt by the citizens of Moldova as state capture diverts funds that should go into public investment and public services. As of 2020, the poverty rate in Moldova was 26.8% among the entire population and 26% among children, and a shocking 35.7% among children in rural areas (Statistics Moldova 2021). With a large proportion of the population dependent on remittances (Expert Grup 2018b), large numbers of workers continue to leave the country, exacerbating the brain drain (Longhurst 2021).

It was against this background that Sandu clearly struck a chord with the electorate on her anti-corruption platform during the presidential election campaign (Longhurst. 2021)

Judiciary

While judicial reforms have ben frequently attempted over the last two decades, the judiciary remains weak and unable to comply with basic principles set down in Moldovan law that “judges shall be independent, impartial and immovable and shall be subordinate only to the law” (Law on the Status of the Judge, Article 1(3)).

Judicial reforms introduced since 2009 include (Vidaicu 2021):

- increased government spending on the justice sector and a considerable increase in judges’ wages

- a reform of the Superior Council of Magistracy (SCM), the regulatory and oversight body for the judicial system

- a new evaluation system for the performance appraisal of judges

- new measures related to disciplinary liability

- the establishment of mandatory random allocation of court cases through a new IT system

- the prohibition of third-party communication with judges

- a role for the new National Integrity Authority to assess incompatibilities, financial disclosures and potential conflicts of interest in the judiciary

Despite these efforts, a report by the International Commission of Jurists (2019: 44) found that the judiciary remains beholden to special interests, writing that:

“both the public and the stakeholders of the justice system typically do not yet perceive an amelioration in access to justice or in the independence of the judiciary. The ICJ delegation met several stakeholders who said the situation of the independence of the judiciary is far worse now than in 2012 – some even said worse than during the Soviet times – and almost none had confidence that it would improve. The leitmotiv the ICJ heard is that the reform process left Moldova with, broadly, good legislation but with a poor, insincere and ineffective implementation.”

The report particularly highlighted the “mentality of excessive hierarchy” and identifies the role of judges “as merely notary” to the work of the prosecutors’ offices.

More recently in January 2021, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in its Resolution 2357 expressed concern that Moldova exhibits a:

“slow pace of the reform of the judiciary … in particular, insufficient progress made in the field of corruption prevention in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors…. [PACE urges Moldova] to adopt the expected legal and constitutional amendments, in line with the recommendations of the Venice Commission; to improve the independence, accountability and efficiency of the judiciary.”

According to the Public Opinion Barometer of Moldova, trust in the courts among the population is extremely low. More than 60% of the population either somewhat distrust (31%) or highly distrust (34.4%) the courts (Institute for Public Policy 2021). In fact, the high level of (perceived) corruption in the judiciary is believed to “prompt sympathy in public opinion for reforms and initiatives that risk undermining the independence of the judiciary in the name of ‘anti-corruption’” (ICJ 2019: 44).

Political interference has played a large role in rendering the judiciary ineffective and sustaining state capture. According to Longhurst (2021), this reached its apogee under Plahotniuc, whose party started to exert control over the judiciary in 2013 (including the Constitutional Court and Public Prosecutors Office), and by 2016 the PDM enjoyed effective control over key positions such as the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

In 2017, TI Moldova highlighted the problematic system of promotions in the judiciary and concluded that “the selective approach regarding appointments and promotions suggests that the SCM and the parliament promotes loyalty over merit” (TI Moldova 2017: 19).

This view is corroborated by the GRECO’s second compliance report from 2020 in which it expressed continued concern about the composition of the SCM, the promotion and evaluation of judges and prosecutors, and how decisions about these are made in the council (GRECO 2020).

Another indicator of state capture in the judiciary is the lack of action when it comes to large corruption scandals (Longhurst 2021). Examples include the Russian Laundromat scandal and the theft of US$1 billion between 2012 and 2014 (Longhurst 2021).

Concerningly, the authors of the Monitoring the Selectivity of Criminal Justice report (2020-2021) found evidence that during the reporting period that both the Prosecutor General’s Office and the courts “have been exposed to inappropriate influence by the interest group known as ‘Platon’s group’” (Rata and Tarna 2021, p.65).

The study monitored 43 criminal cases to see whether justice was applied selectively. The report found that, unlike in the previous monitoring period, individuals under investigation are less likely to try to overcome their legal problems by actively exploiting close relationships to political parties in power. However, the authors still identified cases where “the proximity of the subjects to the governing party coincided with the issuance of favourable rulings in their case” (Rata and Tarna 2021: 7). They highlight that the “phenomenon of selective justice [in Moldova] may be driven not only by political interests, but also by the interests of business groups or even criminal groups” (Rata and Tarna 2021: 20).

As the justice sector continues to (partly) reflect and/or defend the interests of oligarchs tied to the previous administration, the PAS government has proposed another series of reforms in the justice sector. In August 2021, the new PAS Justice Minister highlighted two key areas for reform (Necsutu 2021a):

- creating a better legal framework to confiscate illicitly obtained funds

- establishing an external and extraordinary evaluation of judges and prosecutors

In relation to the second point, Sandu called on the SCM to address corruption within their organisation while she was prime minister in 2019 and threatened to otherwise push reform “from above”. This led to the SCM forcing the resignation of several senior judges in 2019 who were seen as close to the PDM, apparently in an effort to secure the support of the new administration. However, given the speed of these dismissals, they were not conducted in compliance with the relevant legal procedures (Rata and Tarna 2021: 10).

After failing in 2019 to follow through on her plans to subject judges to external evaluation when her government was toppled by the PSRM (Rata and Tarna 2021: 10), Sandu’s new PAS administration has proposed a law to establish an ad-hoc committee to vet the integrity of the candidates for administrative positions in the Superior Council of Magistracy, the Superior Council of Prosecutors and their specialised bodies.

In December 2021, the Venice Commission (2021b) of the Council of Europe issued an opinion on the draft law “on Some Measures related to the Selection of Candidates for Administrative Positions in Bodies of Self-Administration of Judges and Prosecutors and the Amendment of some Normative Acts.”

While the Venice Commission concluded that the proposed procedure is balanced, they recommended including clearer criteria for the members of the selection committee as well as clear assessment criteria for the candidates as well as the protection of the private and family life of those assessed (Venice Commission 2021b).

In interviews conducted for this paper, TI Moldova also cautioned that anti-corruption reforms in the judiciary are necessary but need to be executed with care. Rather than firing judges and prosecutors en masse that are loyal to the old regime, they contended that some of the experienced judges need to be retained. They also argue that experts, civil society and investigative journalists should be involved in the selection and retention process of judges and prosecutors, in particular to help with the prevention of the politicisation of appointments.

Stocktake of progress in tackling corruption over the last decade

In practice, over the last decade, anti-corruption initiatives have been riven by partisanship. Key anti-corruption institutions have been repeatedly abused to persecute political opponents and economic competitors. Particularly when it comes to investigating and sanctioning cases of grand corruption, the buck is passed back and forth between the National Anti-Corruption Centre, the prosecutors’ office, the Internal Protection and Anti-Corruption Service of the Ministry of the Internal Affairs and the National Integrity Authority, with none keen to take the lead (Goinic 2021: 3). The Monitoring the Selectivity of Criminal Justice report (2020–2021) comes to a similar conclusion, stating that “there were cases when the criminal prosecution body avoided investigating obvious examples of corrupt political elements involving representatives of the ruling party” (Rata and Tarna 2021: 64)

Legal framework

In recent years, Moldova has developed a relatively robust legal framework against corruption. A 2020 review of UNCAC found that most of its provisions have been adopted by national legislation, although some loopholes remain (Freedom House 2020).

However, the practical application of anti-corruption legislation has been found to be unsatisfactory in a number of areas described below. (Freedom House 2020: 7)

Preventive anti-corruption policies and practices (UNCAC Articles 5 and 6)

While anti-corruption policies have been adopted at the national level, they are not fully enforced in practice. A survey found that there is often a lack of awareness and/or understanding among public officials about anti-corruption practices. In addition, there has been no periodic review of legal instruments and administrative policies. The Freedom House (2020) report also finds that anti-corruption policies still do not have the necessary infrastructure and the required conditions to remain “free from undue influence”.

In 2016, under considerable pressure from international partners and the European Union, Moldova passed two new laws. The first, law no.132/2016, established a new National Integrity Authority (NIA) to replace the previous Integrity Commission (National Integrity Authority 2017).

The second, law no.133/2016, introduced a requirement for public officials to declare their assets and interests, which would be subject to verification by the NIA, a body that could apply sanctions to those who breached the regulations (Goinic 2021: 2).

The NIA is mandated to launch formal investigations into an official’s income and asset declaration either on its own initiative or in response to an external request.

Moreover, in 2018, a new requirement stipulated that public officials must declare their assets to the NIA electronically and that, after review, this will be made public at https://portal-declaratii.ani.md/ (Goinic 2021).

Measures to prevent corruption in the public sector and codes of conduct (UNCAC Articles 7 and 8)

Such measures have been adopted but are inadequately implemented. Regarding recruitment, Freedom House (2020) criticises the lack of transparency in recruitment for senior public office positions and the limited number of public officials that fulfilled training requirements.

Political financing is also a major area of concern, where, according to Freedom House (2020: 14):

“the respective deficiencies are related to: the ban on donations from Moldovan citizens working abroad; the high number of donations to political parties from individuals and legal entities which reach the yearly contribution max; the absence of supervision or enforcement of the rules on funding political parties; and the ineffectiveness of sanctions for violation of party financing rules, including the low level fines for contravention.”

Similarly, the funding of political parties is still not transparent, which allows a small number of wealthy people to dominate politics, given that (Freedom House 2020: 15):

“current provisions on the ceiling of donations … still allow majority candidates to collect substantial resources from a small circle of people, which facilitates cartel arrangements and strongly favours the candidates who have access to resources.”

Public procurement and management of public finances (UNCAC Article 9).

While a regulatory framework has been established and is applied, the principles of transparency and access to public information are generally neglected (Freedom House 2020).

Preventive measures relating to the judiciary and prosecution services (UNCAC Article 11).

National legislation in theory offers means to ensure the integrity of the judiciary and prosecution, however, as discussed above preventive measures have been shown to be ineffective, and rules around ethical behaviour are often not applied.

The fourth round of evaluation by GRECO, dedicated to the prevention of corruption among deputies, judges and prosecutors, also showed that progress had been made but was not sufficient. Three main areas of concern were highlighted: ethics of the members of parliament (MPs), immunity of the MPs, and the accountability of prosecutors (for further details, see Transparency International Moldova 2020c).

Corruption prevention in the private sector (UNCAC Article 12).

Broadly speaking, the private sector has not adopted important measures such as ethics codes, provisions on conflicts of interest or the revolving door or whistleblower protection mechanisms (Freedom House 2020).

Preventing money laundering (UNCAC Article 14).

The regulations have been streamlined with the most recent European instruments (European Union Directive 2015/849). However, while the law on anti-money laundering entered into force in December 2020, secondary legislation is still missing (European Commission and HR/VP 2021).

However, laws were adopted in 2018 that could reinforce money laundering, including the law on citizenship by investment (which is temporarily suspended), the law on voluntary declaration and tax incentives, and the decriminalisation of a series of offences. Business entities, for instance, are exempted from criminal punishment in exchange for paying double the damage caused by the offence (Freedom House 2020: 39f).

Asset recovery (UNCAC Articles 51-58).

While some reforms have been introduced, and this appears to be a priority of the new PAS government (Necsutu 2021a), implementation is also lagging. There is unfortunately no data available on assistance requests from other countries or the number of requests for confiscation of the proceeds of crime (Freedom House 2020).

The 2021 UNICRI report finds that, while the country has seen policy reform measures to counter illicit financial flows and organised crime, there is still room for improvement. The report recommends (UNICRI 2021: 4):

- bolster transparent mechanisms for the seizure, confiscation, management and distribution (ideally to high-priority development needs) of illicitly obtained assets

- enable the Criminal Asset Recovery Agency (CARA) to take over these tasks

- make extended confiscation and confiscation of equivalent value as a norm in the criminal justice system

- strengthen non-penal mechanisms for the seizure and confiscation of assets

- establish regular dialogue with police and prosecutorial focal points in other key countries regarding the seizure, confiscation and recovery of assets

Institutional reform

A report by the European Commission and HR/VP (2021: 10) recognises that some efforts have been made at the policy and institutional levels, noting in particular:

- the increase in the annual budget of anti-corruption institutions (especially the National Integrity Authority, Criminal Asset Recovery Agency, Financial Investigation Unit)

- a two year extension of the 2017–2020 National Integrity and Anti-corruption Strategy

- in May 2020, Moldova joined the peer review programme of the OECD Anti-corruption Network for Eastern Europe and Central Asia (ACN) – the Istanbul Anti-Corruption Action Plan (IAP)

- the adoption of amendments to the law on the National Integrity Authority regarding assets and conflicts of interest declaration

The National Integrity Authority

The establishment of the National Integrity Authority in 2016 was initially welcomed as a step forward in replacing the ineffective Integrity Commission (Prohnitchi 2017: 13). However, more recently, international observers have criticised the authority’s lack of independence from political forces as well as its inefficiency (GRECO 2020).

Firstly, political influence seems to continue to play a role in its operations. On one hand, the National Integrity Authority has investigated cases related to the unjustified property of several former high ranking officials, including former presidents, MPs, judges and prosecutors (Goinic 2021: 2).

However, in 2020, only a small minority (4%) of total reports issued were related to officials with sizeable political influence, whereas around 45% of NIA reports that identified integrity violations related to lower-level officials such as local counsellors (Goinic 2021: 2). In addition, the NIA has in the past refused to open cases into leading political figures who are still in power. Notably, the NIA only conducted investigations into former PDM leader Plahotniuc after he had fled the country, and only published the results of their investigation into Violeta Ivanov, the Shor Party candidate in the 2020 presidential elections, well after the elections had been held (Goinic 2021: 2). Finally, a 2018 evaluation of judgements from the supreme court of justice concluded that that NIA were disproportionately dismissed when they involved senior officials (Legal Resources Centre from Moldova 2018: 4).

The NIA continues to struggle with insufficient financial and legal resources. As of January 2021, of the 43 integrity inspector positions the agency expected to recruit, only 19 were filled (Goinic 2021: 3). Goinic (2021: 3) suggests that this “perpetual understaffing” is the result of a combination of rigorous merit-based recruitment policies, low salary and the exclusion of candidates with political affiliations.

According to the 2021 National Integrity Authority activity report, in the first nine months of 2021, a total of 261 cases were opened against members of parliament and ex-MPs, judges, public officials, prosecutors and a mayor (National Integrity Authority 2021: 15).

Final thoughts

Ultimately, Baltag and Burmester (2021) argue that the only way that governance reforms in the country can be truly successful is when new norms are embedded at the societal level and translated into politics. They contend that the election of PAS, which ran above all on an anti-corruption platform, can be interpretated as a positive sign for this change as there is a widespread consensus among the population that corruption needs to be curbed.

Whether this popular consensus endures the political tribulations to come as PAS tries to implement its proposed anti-corruption measures remains to be seen. Longhurst (2021) cautions that one should not underestimate that vested interests of deeply entrenched elites against reforms, especially in the justice sector, and predicts there will be considerable backlash against good governance reforms, as well as highlighting the seemingly intractable Transnistria issue as a barrier to sustainable reform.

Longhurst (2021) suggests the following will be crucial velements of any strategy to overcome state capture in Moldova:

local, national and international development strategies need to be aligned and coupled with “exacting, yet reachable and verifiable conditionality by international donors” (Longhurst 2021: 89)

the cost of engaging in corruption should be increased while incentives to act in accordance with the rule of law are strengthened. This can be achieved through judicial reform, the prosecution of corrupt officials (especially those involved in large scale scandals), and seeking to shake up the country’s political economy through measures intended to stimulate the growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs)

finally, Baltag and Burmester (2021) argue that a key means of buttressing sustainable anti-corruption momentum is for PAS to more meaningfully involve civil society actors in their reform package.

Annex 1: Moldova’s performance in international governance indices relative to other Eastern Partnership countries

WGI Control of Corruption score (-2.5 to +2.5)

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Armenia |

-0,56 |

-0,35 |

-0,18 |

0,03 |

|

Azerbaijan |

-0,89 |

-0,84 |

-0.84 |

-1,05 |

|

Belarus |

-0,26 |

-0,19 |

-0,04 |

-0,17 |

|

Georgia |

0,74 |

0,71 |

0,70 |

0,60 |

|

Moldova |

-0,80 |

-0,72 |

-0,64 |

-0,57 |

|

Ukraine |

-0,78 |

-0,87 |

-0,76 |

-0,78 |

|

Regional average |

-0,46 |

-0,38 |

-0,29 |

-0,32 |

Corruption Perceptions Index score (out of 100)

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Armenia |

35 |

35 |

42 |

49 |

|

Azerbaijan |

31 |

25 |

30 |

30 |

|

Belarus |

44 |

44 |

45 |

47 |

|

Georgia |

56 |

58 |

56 |

56 |

|

Moldova |

31 |

33 |

32 |

34 |

|

Ukraine |

30 |

32 |

30 |

33 |

|

Regional average |

37,8 |

37,8 |

39,1 |

41,5 |

The Economist Democracy Index

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Armenia |

4.11 |

4.79 |

5.54 |

5.35 |

|

Azerbaijan |

2.65 |

2.65 |

2.75 |

2.68 |

|

Belarus |

3.13 |

3.13 |

2.48 |

2.59 |

|

Georgia |

5.93 |

5.50 |

5.42 |

5.31 |

|

Moldova |

5.94 |

5.85 |

5.75 |

5.78 |

|

Ukraine |

5.69 |

5.69 |

5.90 |

5.81 |

|

Regional average |

4.58 |

4.60 |

4.64 |

4.59 |

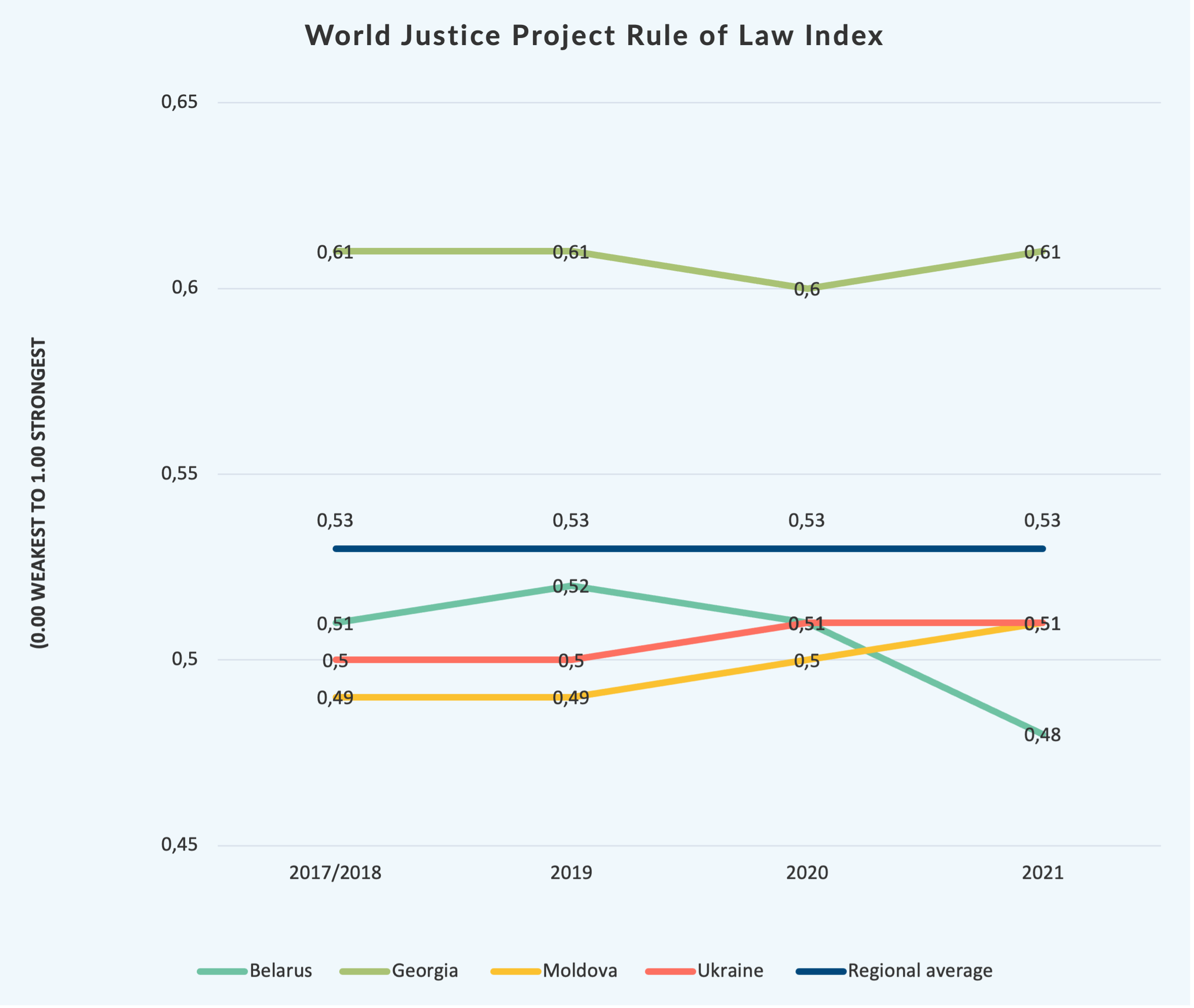

World Justice Project Rule of Law Index

|

|

2017/2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Belarus |

0.51 |

0.52 |

0.51 |

0.48 |

|

Georgia |

0.61 |

0.61 |

0.60 |

0.61 |

|

Moldova |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.50 |

0.51 |

|

Ukraine |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.51 |

0.51 |

|

Regional average |

0,53 |

0,53 |

0,53 |

0,53 |

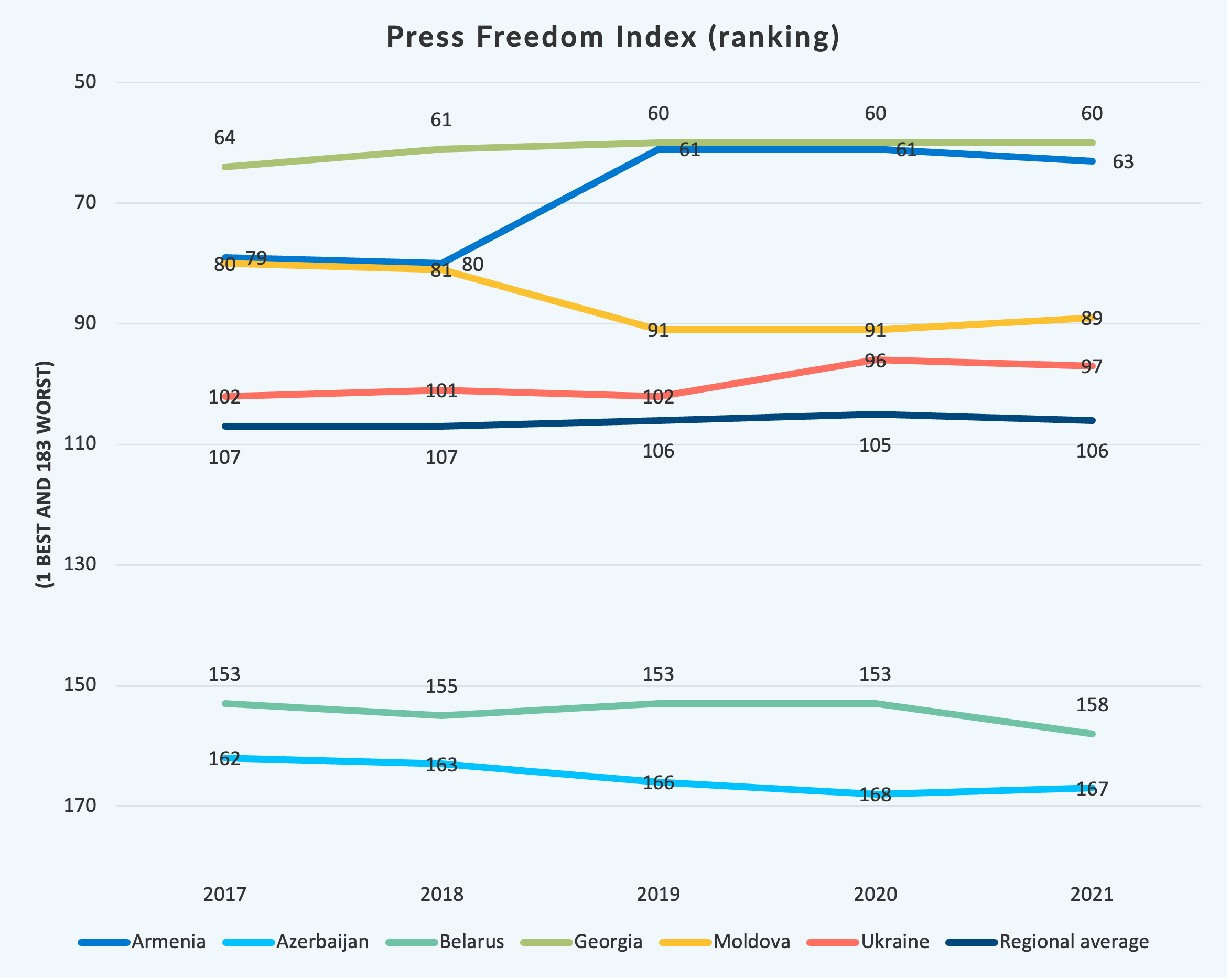

Press Freedom Index (rank)

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Armenia |

79 |

80 |

61 |

61 |

63 |

|

Azerbaijan |

162 |

163 |

166 |

168 |

167 |

|

Belarus |

153 |

155 |

153 |

153 |

158 |

|

Georgia |

64 |

61 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

|

Moldova |

80 |

81 |

91 |

91 |

89 |

|

Ukraine |

102 |

101 |

102 |

96 |

97 |

|

Regional average |

107 |

107 |

106 |

105 |

106 |

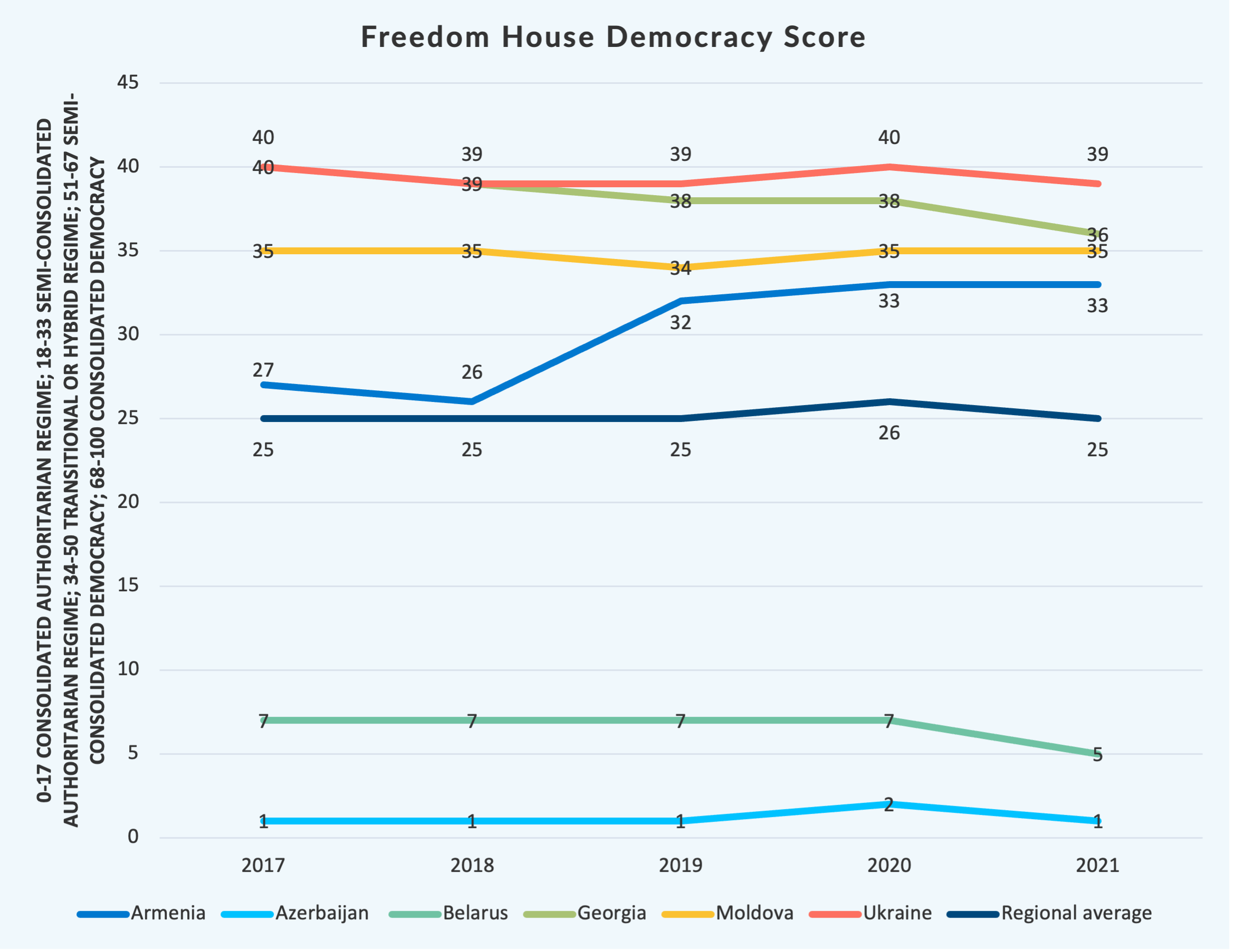

Freedom House Index – Democracy Score

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Armenia |

27 |

26 |

32 |

33 |

33 |

|

Azerbaijan |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

Belarus |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

|

Georgia |

40 |

39 |

38 |

38 |

36 |

|

Moldova |

35 |

35 |

34 |

35 |

35 |

|

Ukraine |

40 |

39 |

39 |

40 |

39 |

|

Regional average |

25 |

25 |

25 |

26 |

25 |

- Tofilat and Negruta (2019) estimate that between 2014-2014 about US$70 billion were laundered through Moldova, which is equivalent to more than 10 times the annual GDP of the country.