Query

An overview of corruption and anti-corruption efforts in Moldova with a focus on the healthcare and procurement sectors.

Summary

The Republic of Moldova, a landlocked country in South East Europe, gained its independence with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Its troubled transition to democracy and a market economy has been accompanied by political tension between pro-Western and pro-Russian factions, as well as a dependency on remittances. All this has created a conducive environment for corrupt practices to thrive (Chayes 2016).

Surveys and anecdotal evidence suggest that corruption in the country appears to be becoming more engrained in politics and society, affecting the quality of life for ordinary Moldovans. In particular, the consolidation of an oligarchic elite’s position at the reins of the state apparatus is seen to have fuelled corruption in politics, business and public administration. An example of the country’s problem with grand corruption was provided by the 2014 banking scandal, which led to the imprisonment of the former prime minister and precipitated an economic crisis.

While substantive legislative reforms have been undertaken, serious political commitment to their implementation is required to tackle the endemic forms of corruption that exist in various sectors – including healthcare, procurement, judiciary and law enforcement. This paper also considers the role of external partners in Moldova’s anti- corruption efforts.

Overview of corruption in Moldova

Background

Moldova emerged as an independent parliamentary republic following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 (The World Bank 2017; BBC News 2017). Russian forces, however, remain on Moldovan territory, east of the Nistru River, supporting the breakaway region of Transnistria, which is mostly inhabited by Ukrainians and Russians, but also has a sizable ethnic Moldovan minority (CIA 2017).

Years of Communist Party rule in the post- independence period ended with violent protests and a rerun of parliamentary elections in 2009 (CIA 2017). Since then, a series of pro-EU ruling coalitions have governed Moldova (CIA 2017). Legislative gridlock and political instability due to infighting in these coalitions resulted in the collapse of two governments (CIA 2017). January 2016 saw the political impasse end when a new parliamentary majority, led by the Democratic Party (PDM) as well as defectors from other parties, supported the appointment of Pavel Filip as prime minister (CIA 2017). These defectors were reportedly “convinced” by the oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc through bribes and blackmailing to “cross the floor”97be60b786f1in parliament (Transparency International Moldova 2017a). The parties that lost their members of parliament (MPs) to the Democratic Party include:

- Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM) lost 1 out of 25MPs

- Party of Communists of the Republicof Moldova (PCRM) lost 14 out of 21MPs

- Liberal Democratic Party ofMoldova (PLDM) lost 17 out of 23MPs

- Liberal Party (LP) lost 2 out of 13MPs

It should be noted that while the lawmakers were anointing Filip as prime minister, more than 3,000 protestors had surrounded and breached the parliament demanding snap elections (VOA News 2016). The protestors were against Filip because of his close connection with Plahotniuc (VOA News 2016). The state of affairs was so severe that the prime minister had to take this oath late at night and in secret (Roman 2016).

Despite being the poorest country in Europe, Moldova has made significant progress in reducing poverty and promoting inclusive growth since the early 2000s (The World Bank 2017).

The Moldovan economy is small and lower middle-income based, expanding by 5% annually (The World Bank 2017). It relies heavily on agriculture and annual remittances of about

US$1.12 billion from the approximately one million Moldovans working in Europe, Russia and other former Soviet Bloc countries (BBC News 2017; CIA 2017). Having few natural energy resources, Moldova imports virtually all of its energy supplies from Russia and Ukraine. Moldova's dependence on Russian energy is demonstrated by its US$5 billion debt to Russian natural gas supplier Gazprom, largely as the result of unreimbursed natural gas consumption in the breakaway region of Transnistria (CIA 2017).

European integration has anchored the government’s policy reform agenda and has resulted in some market-oriented progress (CIA 2017; The World Bank 2017). The Association Agreement and a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement between Moldova and the European Union (EU) were signed in June 2014 (The World Bank 2017). However, the past several months have seen explicit changes in Moldovan politics and foreign policy with the election of pro-Russian Igor Dodon as president in November 2016 (Miller 2017).

The decision of the constitutional court to strike down constitutional amendments mandating parliamentary selection of the president paved the way for the first direct presidential election since 1996 (Freedom House 2017). Thus, the election of President Dodon may be viewed as a loss of trust in pro-European leaders (Tanas 2017b). At the beginning of 2017, Dodon visited Russia and said his country should scrap a trade deal with the EU and instead sign one with the Russian-backed Eurasian Union. At present, President Dodon and Prime Minister Pavel Filip are at loggerheads, criticising each other’s policies on relations with Russia and with Transnistria (Miller 2017).

Lying at the crossroads of the east and west, Moldova is frequently caught between such powerful geopolitical interests with disparate values (Transparency International 2015).

However, the Moldovan political landscape should not be viewed solely through the lens of its geopolitical orientation. "Domestic stasis" is said to be likely to prevail until at least the 2018 parliamentary elections (Devyatkov 2017; Miller 2017). State capacity, already impaired by corruption, is seen to have been further weakened with President Igor regularly challenging parliament (Minzarari 2017).

Politicians all along the political spectrum in Moldova have a reputation for being corrupt, as is best evidenced by the theft of US$1 billion (12% of GDP) from the country’s banking system in 2014 (Miller 2017). Endemic corruption, lack of transparency andaccountability, coupled with a high public debt and low business confidence has severely affected the country (Miller 2017; The World Bank 2017; Transparency International 2015).

Corruption in Moldova has gone through severalstages over the last decade, from being generally pervasive, to the “politicisation” of the fight against corruption through the elimination of political rivals and business competitors and ultimately to state capture (Transparency International Moldova 2017a). This process of state capture has been fuelled by the sale of parliamentary votes in the legislature, the flourishing of cronyism, clientelism, and rent-seeking in the executive, the paralysis of the judiciary due to nepotism, and the recent curbing of independent media (Gherasimov 2017; Transparency International Moldova 2017a).

Recent attempts to legalise money and property potentially acquired fraudulently, 39995af2d09c along with the adjustment of the electoral system to the advantage of the governing party 9a5552a54033 (which under current conditions risks not passing the electoral threshold in the next parliamentary elections) showcase the level that Moldovan state capture has reached (Transparency International Moldova 2017a).

Moldova’s political establishment is believed to be controlled by the private sector in general, and by business magnate Vladimir Plahotniuc in particular (Chayes 2016). The "Kleptocratic network" is formed of elements from the government, private sector, criminal elements, lower level officials, active facilitators and external enablers (Chayes 2016).

The increased concentration of power in Plahotniuc’s hands, behind the façade of the Democratic Party, is a peculiarity of Moldovan state capture (Gherasimov 2017). With a weak civil society and lack of societal pressure for accountability, observers believe a concerted effort by the EU to drive reform may be needed (Gherasimov 2017). The Association Agreement, signed with the EU in 2014, maybe one such viable political accountability mechanism that can provide the necessary oversight for anti-corruption reforms to be implemented by the Moldovan government (Gherasimov 2017).

Despite the lack of political will for reform and the weaknesses of state institutions (IMF 2017), there are several initiatives with potential to facilitate meaningful change in the country. Some progress is discernible in terms of legislative change, support from external partners and lessons from successful case studies in neighbouring regions. These are discussed throughout the paper, and a section at the end focuses on the role of external partners.

Although the direction and intensity of anti- corruption efforts in Moldova remain to be seen, combatting corruption has been among the top priorities of all governments since 2009, and shall remain significant in the run-up to the 2018 elections (Gribencea 2017; Végh 2017).

Extent of corruption

Transparency International ranked Moldova at the 123rd place alongside with Azerbaijan, Djibouti, Honduras, Laos, Mexico, Paraguay and Sierra Leone in the 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). With only 30 points out of 100, this was its lowest score yet, indicating that the situation is perceived as deteriorating (Transparency International 2017; Vlas 2017a).c2705d5b071d Countries with a low CPI score are said to be plagued by "untrustworthy and badly functioning public institutions" where anti-corruption laws exist only in name and people are frequently confronted with bribery and extortion (Transparency International 2017; Vlas 2017a).

According to the WorldwideGovernanceIndicators,Moldova's percentile rank improved marginally between 2010 and 2015 in the fields of voice and accountability (46 to 47), political stability and absence of violence/terrorism (33 to 34), and regulatory quality (49 to 51)bf74c7ef860b. However, other fields during the same period displayed a deterioration in percentile ranks, these include government effectiveness (31 to 29), rule of law (32 to 40), and most importantly, control of corruption (29 to 17), which saw the sharpest drop among all other indicators (The World Bank 2016).

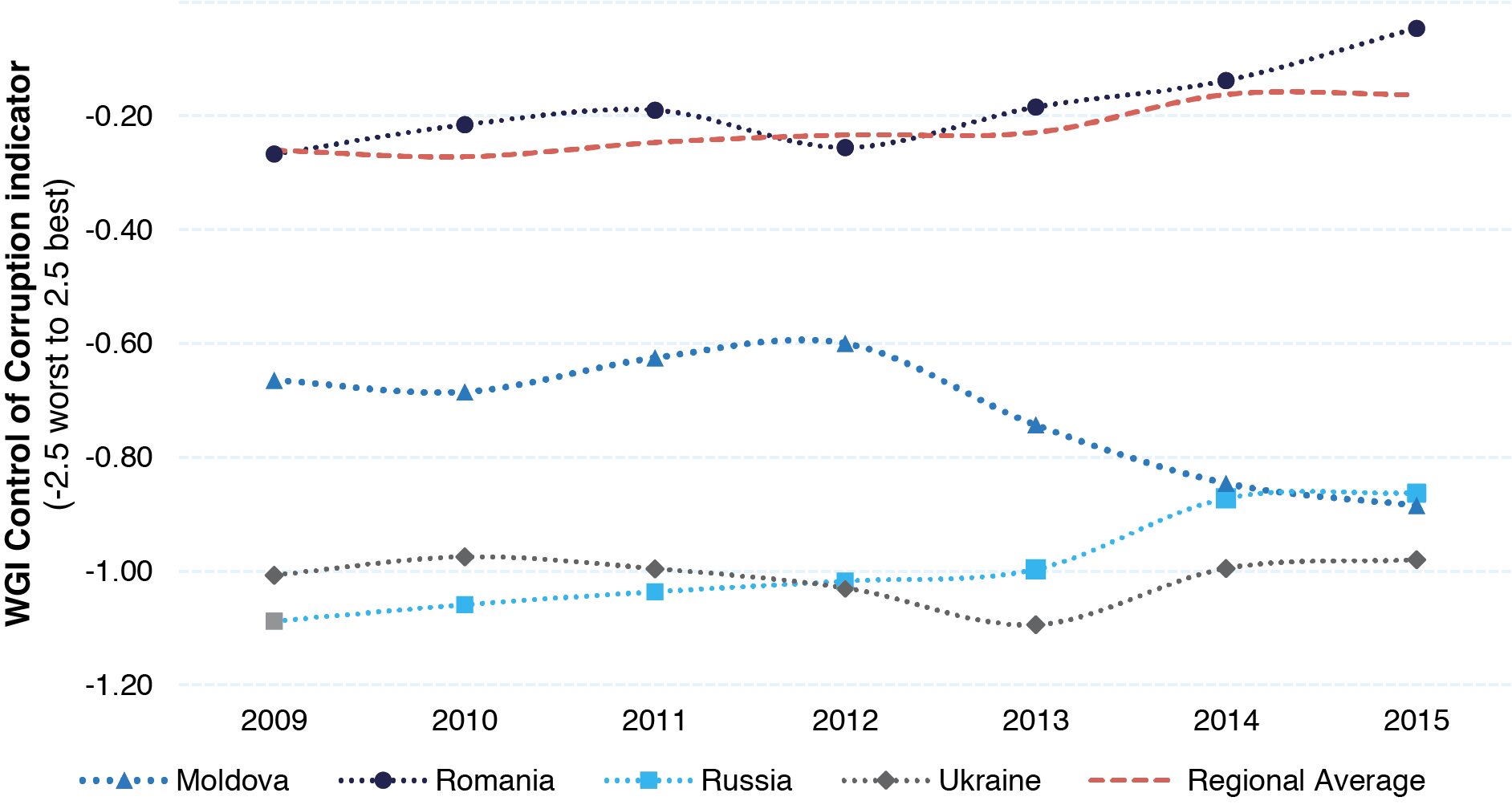

As shown in the graph below, when compared to its regional neighbours, perceptions of corruption in Moldova have worsened over the past six years and have begun to converge with the levels observed in Russia and Ukraine. Indeed, Ukraine, Russia and Moldova are consistently under the regional average in control of corruption for Eastern Europe, which ranged from -0.21 in 2005 to -0-16 in 2015.

WGI Control of Corruption Indicators: Eastern Europe 2009-2015 39d78983856c

The 2016 Global Corruption Barometer survey results revealed some interesting trends, including:

- Moldovans are particularly likely to think corruption is one of the top problems facing their country, with two-thirds of respondent citizens saying that it should be a priority for the government.

- Three-quarters of the respondents think that their parliamentary representatives are very corrupt.

- Around two in five households, who had accessed public services, including public health services, paid a bribe in Moldova.

- More than half of the respondents rate their government badly at fighting corruption.

- Its citizens rate Moldova poorly across all of the key questions in the Global Corruption Barometer survey.

With respect to the bribery risks that businesses in Moldova may face, the country is ranked 144 out 199 countries for 2016, with a risk score f23066ac3544 of 70 out of 100 by TRACE Matrix. Moreover, the 2017 World Bank ease of Doing Business overall rank 7bb7d55a1c21for Moldova is 44, with areas such as dealing with construction permits (rank 165), getting electricity (rank 73) and enforcing contracts (rank 62) displaying a need for considerable improvement. The 2017 Index of Economic Freedom published by the Heritage Foundation ranked the republic 110 out of 180 countries, citing that the Moldovan government’s “overall commitment to enhancing the entrepreneurial climate and advancing economic freedom has been uneven”.

Freedom House views Moldova as a multi-party democracy that holds regular, credible elections, but “struggles with serious corruption among public officials and within the judicial system”. Hence it has rated the country as only partly free with a freedom rating e58f3ebdd385 of 3/7 for 2017 (Freedom House 2017).

Forms of corruption

Grand corruption

Vlad Plahotniuc, Chairman of the Democratic Party (PDM) and head of the ruling coalition is widely seen as driving force of corruption in Moldova (Moldovan Politics 2017). Apart from being the wealthiest businessman in the country, he is the top oligarch with "real power" running “the show from behind the scenes" (Coffey 2016; Moldovan Politics 2017). Plahotniuc is described as Moldova’s "most feared figure", with a “toxic reputation” (Higgins 2016). Although considered as nominally pro-EU, he has been accused of being "pro-Plahotniuc and pro-corruption" by Natalia Morari, the host of a Moldovan political talk show (Higgins 2016). Her show provided extensive coverage of anti-government protests fuelled principally by rage at Plahotniuc. Following this, Morari claims to have been threatened by one of the businessman’s associates in 2016 with a smear campaign featuring a sex tape illegally filmed in her own bedroom (Higgins 2016).

As mentioned earlier, the peculiarity of Moldovan state capture is that the country is essentially “owned” by a single person, creating room for monopoly and grand corruption in all spheres of governance (Higgins 2016; Levcenco 2016; Gherasimov 2017). Moldovans feel that when it comes to governance they have a "poisoned choice to make", between a corrupt oligarchy that has only furthered corruption in the system, and parties that are pro-Russian (Tomkiw 2016). As one Moldovan journalist put it, “both of them are bad decisions” (Tomkiw 2016). The lack ofgovernment control and oversight is seen as the leading cause of corruption in Moldova with 90% of citizens believing that their country is governed only in the interest of some groups (Centre for Insights in Survey Research 2016).

A prime example of this is locally known as the "theft of the century", when US $1 billion disappeared from three Moldovan banks, namely, Banca de Economii, Unibank and Banca Socială (Whewell 2015; Tanas 2017b). This haemorrhage of money was made possible through a web of toxic loans, asset swaps and shareholder deals (Balmforth 2015). The fraud wiped 12% off the country's GDP and involved some degree of complicity from many of those in power since 2009 (Balmforth 2015). In fact, before the theft, money was laundered using funds of illegal and doubtful origin within the region through a banking system propped up by the judicial system and under the instruction of those vested with power (Transparency International Moldova 2016).

The National Bank took over the banks, covering the failed banks’ obligations to depositors, including pensions and social payments, to the tune of 13.5 billion MLD, (about US$1 billion) (Balmforth 2015). Converting the billion-dollar theft to public debt tripled the size of domestic debt from MDL 7.2 billion (US$409 million) at the beginning of 2016 to over MDL 22 billion (US$1.25 billion) at the end of 2016 (Transparency International Moldova 2016).

The bailout of the looted banks led to a rapid depreciation in the national currency, the leu, stoked inflation and lead to the loss of credibility of the pro-European leaders among the general populace (Balmforth 2015).

The mastermind of the billion-dollar theft and a man at the heart of the Russian Laundromat scandal currently unfolding in Moldova was businessman Ilan Shor (Sanduța 2017). Even as that billion-dollar theft was taking place, a fourth Moldovan bank, Moldindcon bank, was routing US$20.8 billion in Russian money through its accounts as part of the Russian Laundromat,0d00a0fe7265 the biggest money laundering operation ever uncovered in Eastern Europe (Sanduța 2017).

Shor was arrested in 2015 on money laundering and embezzlement charges. Anti-corruption prosecutors say that he laundered more than US$335 million of the stolen billion (Sanduța 2017).

It was Shor's information that led to former prime minister Vlad Filat's prosecution. Shor claimed that he paid a US$250 million bribe to the country’s former prime minister to help him control Banca de Economii, the bank playing the most important role in the massive theft (Sanduța 2017). Despite his arrest and involvement in the scam, and despite being embroiled in the banking fraud, Shor was elected mayor of Orhei, and his ultimate fate is yet to be decided (San Diego Union Tribune 2016).

Earlier in 2017, three years after the scandal came to light, the Moldovan central bank said it was finally in a position to get back some of the looted US$1 billion (Tanas 2017b). Although the government undertook various reactionary measures, including the preparation of a roadmap (see later) to re-instate faith in Moldovan governance after this scandal, with investigations still on-going, the final outcome remains uncertain.

Political corruption

The parliament, followed by public officials, and the prime minister and his cabinet are viewed as being the most corrupt (Centre for Insights in Survey Research 2016).

The extent of political corruption is evidenced by the series of ministers and government officials who have been accused of and arrested on charges of corruption. Particularly noteworthy is the nine-year sentence handed down to former prime minister Vlad Filat (from 2009 to 2013) who was found guilty of abuse of office and corruption after being charged with taking bribes in a US$1 billion bank fraud case (RadioFreeEurope 2016).

However, many believe that the real beneficiaries of the bank fraud are still free, and that Filat was used a scapegoat for the scandal to get rid of the Plahotniuc controlled Democratic Party’s main political opponent (Transparency International Moldova 2017a). This claim is further strengthened by the nature of Filat’s arrest – his immunity from arrest was withdrawn by parliament in haste without following obligatory procedures, and his judicial trial was far from transparent (Transparency International Moldova 2017a). With Filat out of the picture, the oligarchic system in Moldova has been made even stronger with Plahotniuc as the păpușar (puppet master) – the person controlling key state institutions from behind the scenes (Całus 2015).

Recently, anti-corruption prosecutors and National Anti-Corruption Centre officers arrested the Vice- Minister of Economy of Moldova, Valeriu Triboi, in a case concerning abuse of power and substantial damage to the state budget (Vlas 2017c). Triboi allegedly bought, through a third party (the state- founded SA Moldtelecom), a building worth almost MDL 1 million (US$56,000) and then rented it out for 10 years to the state-owned electricity distributor Furnizarea Energiei Electrice Nord. He also allegedly ordered the distributor to repair the building using their state funds to the tune of MDL 4 million (US$224,000) Vlas 2017c).

In November 2016, The Minister of Agriculture and Food Industry, Eduard Grama, was arrested in connection with the bribing of at least two agricultural officials by businessman Tudor Ungureanu to appropriate 30 hectares of land from Stăuceni suburb of Chisinau, belonging to the Wine-making and Wine-culture College (Vlas 2017b). Grama was later dismissed by President Dodon (RadioFreeEurope 2017b).

The Deputy Chairman of the Liberal Party and Chisinau Mayor Dorin Chirtoaca and other city officials were arrested earlier in 2017 on charges of corruption (Tanas 2017a). Chirtoaca is accused of instructing his deputy to sign a contract with Austrian company EME Parkleitsystem GmbH to build parking lots across the city (Tanas 2017a). The National Anti-Corruption Centre claims that the company won this contract due to "concerted actions" from city hall officials (Tanas 2017a).

While the mayor remains under house arrest, Igor Gamreţki, head of the Transport Department of the Capital, has been sentenced to two years in prison in the same case (Crime Moldova 2017; Publika 2017). Chirtoaca’s defenders say his arrest is politically motivated rather than a resultof the government's desire to crack down on endemic graft (Tanas 2017a). In protest, the Liberal Party withdrew from the ruling coalition and a minister in Moldova’s pro-European government and two of his deputies resigned (Tanas 2017a). Such a volatile environment coupled with extensive opacity creates a cultureof impunity where anti-corruption is often used as a political tool to settle scores, as some claim is the case with accusations levelled at Chirtoaca (Business Anti-corruption 2017; Tanas2017a).

Party funding transparency, especially in the wake of the aforementioned changes to the electoral process, which many speculate is to secure the Democratic Party's position in the upcoming elections, was identified as an essential element of combatting corruption in the Priority Reform Action Roadmap adopted by the government in 2016. Presidential elections in 2016 presented a test for Moldovan authorities’ anti-corruption commitments. However, it was noted that these elections were marred by "widespread abuse of administrative resources, lack of campaign finance transparency, and unbalanced media coverage” (EaP CSF2017).

The Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) has recommended the following measures to combat the existing opacity in Moldovan political parties (EaP CSF 2017):

- Revise the legislation on party funding to insert all Group of States against Corruption (GRECO)e88bf421be95 recommendations.

- Cap annual donations to political parties so that individuals can donate no more than four to five of their average salaries, and legal persons around 20 average salaries, in accordance with international practices.

- Permit small donations through banking transfer from Moldovans abroad.

- Amend the law on political parties to include the provisions of Central Election Commission’s regulation on the financing of political parties that refers to donations as well as sanctions for non-compliance with the regulation.

Corruption in business

Moldova's business environment is one of the most challenging in the South East European region and is undermined by pervasive public sector corruption, political instability and a burdensome regulatory environment (Business Anti-corruption 2017; World Economic Forum 2017).

One in seven companies indicate they expect to give gifts in Moldova to “get things done” and one- third of businesses expect to give gifts when obtaining an electrical connection (Enterprise Surveys 2013). Moreover, a survey conducted by TI-Moldova revealed that businesses in the country found corruption, with a score of 4.1400137a749da, to be the fourth most acute problem affecting them (Transparency International Moldova 2015).

Businesses indicate irregular payments and bribes are particularly common when making annual tax payments (World Economic Forum 2017). Nearly half of businesses report that tax officials are likely to ask for an “additional payment” when a tax violation is detected (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Fiscal inspectors are paid an average bribe of MDL 6,011 (US$340) (Transparency International 2015). In one case, a foreign investor, seeking redress, voluntarily reported underpaying taxes, yet found himself being extorted by the tax official assigned to the case (US Department of State 2017).

Companies report that protection of property rights is poor as the government has cancelled several privatisations after accusing investors of failing to meet investment schedules (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Although some companies have been able to obtain compensation from the government in these cases, some had to apply to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) to enforce compensation payments (US Department of State 2017). Businesses are also known to pay an average of 2,675 MLD (US$1,500) to Moldovan law courts (Transparency International Moldova 2015).

Businesses often face bureaucratic procedures that are not transparent, and red tape makes processing licences, registrations and other procedures unnecessarily burdensome (US Department of State 2017). For instance, it takes 27 procedures and 276 days to obtain a construction permit, almost double the average number of steps and days required elsewhere in the region (Doing Business 2017).

At a recent conference, on the 28 June 2017, organised by the Foreign Investors Association on what businesses could do to combat corruption, companies operating in the republic raised various points of concern. A report titled “Corruption: The Most Profitable Moldovan Business” was released stating that the system was rigged against companies as they felt that only “selective justice” operates which “does not protect the economic agents from the abuses of civil servants” (FIA 2017).

Bureaucratic and administrative corruption

The Moldovan public sector is known to lack transparency, and many of its officials are said to commit acts of corruption with impunity (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Discretionary decisions by public officials often provide room for abuse and corruption (US Department of State 2017).

Though the government has taken steps to reduce red tape, the implementation of these measures is still lacking (US Department of State 2017)

The government, recognising the shortcomings of the bureaucracy, came up with a strategy for public administration reform at the national as well as local level (Government of the Republic of Moldova 2016b). The reform’s main objectives are (Government of the Republic of Moldova 2016b):

- rationalising the government’s structure

- reducing the fragmentation of the administrative and territorial structure

- ensuring the work of an efficient system of monitoring, enhancing responsibility and transparency of the performance of authorities, public institutions and state economic entities.

Among other anti-corruption efforts aimed at curbing the bureaucracy, the law on professional integrity testing that came into force in 2014 makes it mandatory for all public servants to undergo an "integrity test" conducted by the National Anti-Corruption Centre (Venice Commission 2014). The test aims to:

- ensure professional integrity, prevent and fight against corruption within public entities

- verify the public agents’ manner to observe work obligations and duties and the conduct rules

- identify, assess and remove the vulnerabilities and risks which could determine or favour corruption acts, corruption-related acts or deeds of corruptive behaviour

- reject inappropriate influences in exercising the work obligations or duties of public agents

Main sectors affected by corruption

Healthcare

Moldovan citizens identified the existence of informal payments and corruption as their primary grievance with the country’s health system in a survey conducted by the Gender Centre in 2013 (Bodrug-Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014). A majority, 72.3%, of Moldovan citizens have frequently resorted to paying bribes to access healthcare (Transparency International Moldova 2015).

Although Moldova inherited one of the most extensive healthcare systems in Europe, with extreme levels of overcapacity in the hospital sector, the economic hardships it encountered during the transition after independence meant that sustaining the scale of this system was "impossible as well as undesirable" (Bodrug- Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014). Thus, between 1998 and 2000, the number of beds for hospital “acute care” was dramatically reduced (Bodrug- Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014). The guiding principle was that lower spending on in-patient care would free resources to be put into primary care services, but this has yet to transpire on any large scale (Bodrug-Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014).

The extensive primary healthcare network in Moldova consists of four types of providers: family medicine centres, rural health centres, family doctor offices and health posts for family doctors’ assistants (feldshers) covering areas with a population of less than 1,000 (Atun et al. 2008).

Though the national regulation for a family doctor requires that they should not oversee more than 1,500 patients, a shortage of medical staff (due to emigration, low pay and alternative career opportunities) have resulted in cases where one family doctor is tasked with caring for a patient list two or three times the prescribed limit, often in exchange for facilitation payments (Bodrug-Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014). District general hospitals in the rural areas and municipal general hospitals in Balti and Chisinau form the secondary level of care (Atun et al. 2008). Specialist services are provided at tertiary level republic hospitals concentrated in Chisinau (Atun et al. 2008).

Life expectancy at birth in 2015 was 71.6 years. However, the growing mortality rate coupled with decrease in the total number of fertile women has meant that percentage of the population over 65is on the rise (UNDP 2016b). This growth makes the Moldovan demographic “top heavy" and influences the sustainability of the public pension system where the number of taxpayers is decreasing compared to the number of beneficiaries (Bodrug-Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014; UNDP 2016b). Access to healthcare is also a challenge for the aging Moldovan demographic due to infrastructural shortcomings (Bodrug-Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey2014).

An investigation by the Centre for Investigative Journalism showed that, in previous years, public money intended for procurement in health, totalling about 800 million MLD (US$45 million), has only reached the accounts of seven companies – Dita EstFarm, Esculap Farm, Medeferent Grup, Sanfarm Prim, GBG-MLD, Distrimed and Tetis International Co (Rață and Nani 2016). The first four of these companies were included in the 2015 blacklist of the Public Procurement Agency after Moldovan medical institutions faced a drug shortage crisis which, according to officials, was caused by the boycott of these companies as they had delayed the supply of medicines (Rață and Nani 2016). All these companies have escaped punishment and have managed to be removed from the blacklist through court decisions (Rață and Nani 2016).

Dita EstFarm is the market leader in terms of winning tenders for the supply of medicines and medical devices; it has, however, been implicated in corruption scandals (Rață and Nani 2016). The company offered a 10% discount in a deal with the Bosnian group, Bosnalijek, which was later found in the personal account of Chirtoaca, the owner of Dita EstFarm, suggesting the occurrence of kick-back payments (Rață and Nani2016).

As for the use of poor quality medicines, the National Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AMDM) refused to issue certificates of quality for several drugs that Metatron imported to Moldova due to their “doubtful quality” (Rață and Nani 2016). Despite laboratory tests for "Eufilin" showing that it contained impurities, the court of appeal ordered the AMDM to issue certificates of quality for Metatron. Though this decision was cancelled by the supreme court, in another case the supreme court ordered the AMDM to issue certificates of quality for preparations of Amoxan and ampicillin for the same company (Rață and Nani 2016).

A few points ought to be noted to put the damaging the effects of systemic corruption in the healthcare sector in Moldova into perspective. In 2014, more than 90% of the population depended on the public healthcare system (with private hospitals being a rarity), and only 5.3% of GDP was spent on public health expenditure (Bodrug- Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014; The World Bank 2014). Though Moldova spent more than its neighbours – Ukraine (3.6%) and Romania (4.2%), it spent less than Slovenia (6.6%) and Serbia(6.4%).

Currently, healthcare coverage is primarily provided through a combination of mandatory social health insurance (from 2004) through the National Health Insurance Company (NHIC), and limited healthcare services through a number of government funded and internationally funded national programmes. Despite the increase in budget for the NHIC, it has not been enough to meet the growing costs of medical technology and the “top-heavy” demographic (Bodrug-Lungu and Kostina-Ritchey 2014).

Nevertheless, to bring the healthcare sector to international standards, the ministry of healthcare is attempting to change legislation’s focus to preventive and educational programming.

In 2013, the Moldovan e-Health Strategy 2020 was finalised to prioritise e-health services in the country by reducing the extremely high referral rate from the primary sector, encouraging doctors and nurses to adopt and incorporate available clinical guidelines in their daily routines, and ensuring that the quality of hospital care is documented and easily accessible (Praxis Centre for Policy Studies 2013). The Moldovan State Agency on Intellectual Property (AGEPI) and the State Medicines Agency signed a cooperationagreement to improve the protection of intellectual property rights in the pharmaceutical industry to help prevent the spread of counterfeit medicines that can endanger human life and health (Petosevic 2010).

Procurement

Moldova's public procurement processes are deemed to be fraught with a high risk ofcorruption (Business Anti-corruption 2017). The percentage of businesses paying bribes frequently to secure procurement tenders is on the rise – increasing from 35.1% in 2014 to 39% in 2015 (Transparency International Moldova 2015).

International companies do not have to be involved with domestic partners to win deals but they are often known to pay bribes and kickbacks to obtain construction permits and operating licences and to secure government contracts in Moldova (Enterprise Surveys 2013; Business Anti- corruption 2017; World Economic Forum 2017).

Companies operating in the republic reportedly feel that favouritism in decisions of government officials are very normal and there is a high degree of perceived wastefulness in government spending (World Economic Forum 2017).

The public procurement sector lacks effective regulations and continues to suffer from opaque tender processes, which often involve the exercise of political influence (Bertelsmann- Stiftung 2016; US Department of State 2017). In addition, the Public Procurement Agency lacks control mechanisms to detect corruption, its members are known to have frequent conflicts of interests, and law enforcement engagement in this sector remains inadequate (UNDP 2016a).

The poor quality of public procurement is seen as a result of frequent political interference (Business Anti-corruption 2017; UNDP 2016a). An example of this is that even though private businesses compete with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) on a level playing field by law, there are reports that SOEs are often in a better position to "exert influence on decision-makers" (US Department of State 2017).

A recent case of corruption in the procurement sector involved high-level Moldovan officials. Anti- corruption officers and prosecutors arrested four people allegedly involved in a case of passive corruption: the minister of transportation and road infrastructure, Iurie Chirinciuc, interim director of road administration and two heads of construction companies (Vlas 2017d). All of them are suspected of forming a scheme to defraud huge sums of money from road construction that are financed by the European Investment Bank (Vlas 2017d). Minister Chirinciuc together with the corresponding financial agents were forcing the contracted company to subcontract to the affiliated companies. If found guilty, the accused face up to 15 years imprisonment and a ban on holding public office for 10 to 15 years (Vlas 2017d).

In line with the requirements of the Moldova-EU Association Agreement and other international accords the country is party to, the Moldovan government has approved a string of documents, aimed at reforming the public procurement system for the next four years – Strategy 2016-2020 – as well as an action plan for the strategy’s implementation (Government of the Republic of Moldova 2016a). The strategy covers not only the reorganisation of the Public Procurement Agency but also the setting up of a National Agency of Appeals Settlement (Government of the Republic of Moldova 2016a).

To cut through the opacity and establish transparency and fair competition in the procurement process, the ministry of finance, Western NIS Enterprise Fund (WNISEF), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and five local NGOs signed a memorandum of cooperation on the implementation of a transparent and efficient public procurement system in Moldova, called MTender (WNISEF 2017).

The initiative is also supported by the European Union and Transparency International (WNISEF 2017). January 2017 saw the successful launch of the first pilot stage of the new "comprehensive electronic public procurement system – MTender" (WNISEF 2017). According to the WNISEF (2017), the pilot stage demonstrated the effectiveness and reliability of the new system, and a second pilot stage for procedures is scheduled to start in October 2017. It is hoped that a larger number of economic entities will be able to participate in tenders (WNISEF 2017).

Judiciary

The Moldovan judiciary is said to be one of the weakest in the world in terms of independence from the political elite (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Although the constitution provides for an independent judiciary, judicial and law enforcement officials have a reputation for being corrupt and under the influence of ruling officials (Freedom House 2016). It is generally expected that court rulings will favour public officials in court cases in which public authorities are involved (US Department of State 2017).

Judicial neutrality being routinely undermined is a common phenomenon (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Judicial appointments often lack transparency and key positions are often "parcelled out among the ruling parties" (Freedom House 2016). Secret annexes from 2010 of the then ruling coalition revealed that National Anti- Corruption Centre and prosecutor general’s office (PGO) had appointees of the Democratic Party (Transparency International Moldova 2017a).

Furthermore, the hasty appointment of the new prosecutor general has fuelled suspicions that the entire appointment process was orchestrated. Even the president of the supreme court of justice has ties to Plahotniuc (Transparency International 2017a).

Moldovans cite the judiciary as among the four most corrupt institutions in the country (Centre for Insights in Survey Research 2016), while business people state that dubious payments and bribes in return for favourable judgments are very common (World Economic Forum 2017).

Revealingly, 15 former or acting judges and three court bailiffs were arrested by the Moldova Prosecution Office in the Russian Laundromat case towards the end of 2016, and the cases are currently on-going (Vlas 2016).

The Justice Sector Reform Strategy (JSRS) for 2011-2016 was adopted in 2011, and its implementation is part of the EU Association Agreement Agenda signed with Moldova in 2014. Despite the JSRS, the Moldovan society's level of trust in the judiciary is declining (Transparency International Moldova 2017a). According to the public opinion barometer, in November 2011, 74.5% of the population did not trust the judiciary while in October 2016, 89.6% had very little or no trust (Transparency International Moldova 2017a).

Judges' wages have been increased by more than 100% since 2013 in an effort to curb rent-seeking behaviour (Bertelsmann-Stiftung 2016). Although promotions are supposed to be merit-based, it is often the case that judges in favour of the ruling elite are promoted over other deserving candidates (Transparency International Moldova 2017a). Persecution of judges and use of the criminal system to pressure them is not uncommon (EaP CSF 2017).

In 2016, a new law on prosecution was passed, described as a milestone for the reform process in Moldova (Ollendorf 2016). The law seeks to limit prosecutorial power and implement a less partisan process for appointing the prosecutor general (Ollendorf 2016; Business Anti-corruption 2017).

However, the implementation status of these reforms is yet to be tested. Moreover, the Superior Council of Magistrates has blocked other anti- corruption reforms aimed at improving judicial integrity, arguing that they would have affected the independence of judges. These amendments would have permitted the criminal prosecution of judges suspected of passive bribery, influence peddling, money laundering or illicit enrichment (Bertelsmann- Stiftung 2016).

The law on judges’ disciplinary responsibility was created in 2014 (EaP CSF 2017). However, it instituted a far too cumbersome mechanism, which lengthens procedures and leaves ample possibility for overlooking serious complaints (EaP CSF 2017). This can lead to a lack of trust in the existing mechanism with complaints not being submitted, leading to judges being able to continue their activity in spite of disciplinary violations (EaP CSF 2017).

Law enforcement

Police impunity is common in Moldova, and citizens face a high risk of corruption when interacting with the police force: three out of four Moldovans perceive the police as corrupt (Bertelsmann-Stiftung 2016; Business Anti- corruption 2016; Transparency International 2013). Companies have reported low confidence in the reliability of police services in protecting them from crime and enforcing the law (World Economic Forum 2017). Tellingly, four out of five firms pay for private security (Enterprise Surveys 2013).

A large share of corruption offences investigated by the country's anti-corruption authorities involves law enforcement employees (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Ill-treatment in police custody, extended pre-trial detention and poor prison conditions persist despite some improvements in recent years (Freedom House 2016).

Moldova has failed to implement swift and robust anti-corruption police reform, and recent reforms have concentrated primarily on restructuring the agency (Moldovan Politics 2015). A cut to the perks and subsidies enjoyed by police officers has led to a high level of attrition, with many officers routinely leaving the police force, and continuing corruption in the force (Moldovan Politics 2015). UNDP is currently sponsoring a police reform programme (see below).

Customs

Corruption in Moldova's customs administration is said to thrive (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Burdensome import procedures and tariffs are the main obstacles to international trade across Moldovan borders, and corruption at the border and non-transparent customs processes significantly interfere with companies’ business operations (World Economic Forum 2016).

Irregular payments and bribes to customs officials are perceived as commonplace (World Economic Forum 2016), while the judiciary often shields corrupt customs officials from prosecution (Chayes 2016). On the other hand, the costs and time required to comply with import procedures are far below the regional average (Doing Business 2017).

A majority, 68.6% of businesses and 66% of households, report paying bribes in their interactions with customs officials (Transparency International Moldova 2015). According to businesses operating in Moldova, customs bodies are among the most corrupt institutions in the country (Transparency International Moldova 2015)

In a recent example of corruption in this sector, five customs brokers and a customs officer were arrested on suspicion of passive corruption in May 2017 (Crime Moldova 2017). The accused reportedly accepted facilitation payments in order to speed up customs procedures; additionally, they threatened to classify goods in higher categories, which would have imposed onerous tax tariffs on the importers (Crime Moldova 2017).

Legal and institutional framework

Overview

Moldova’s tumultuous transition from being a part of the Soviet Union until 1991 to its current pro- European stance has shaped its legal and institutional anti-corruption framework. The predecessors to the recently adopted National Integrity and Anti-Corruption Strategy for 2017-20 were the National Strategy for Corruption Prevention and Fighting, adopted by parliament in 2004, and the National Anti-Corruption Strategyfor 2011-2015, which was bolstered by the recent Anti-Corruption Strategy as well as the National Strategy for Fighting Against Money Launderingand Financing of Terrorism 2013-2017 (Republica Moldova Parlamentul 2017).

The National Integrity and Anti-CorruptionStrategy for 2017-20 is structured upon the integrity pillars approach, following an evaluation by Transparency International in 2014. It aims to strengthen public sector integrity at all levels, but also engages other stakeholders: civil society organisations (CSOs) will produce parallel monitoring reports while integrity standards in the private sector are intended to be strengthened (Network for Integrity 2017).

The strategy has 130 action items and focuses on eight sectors namely: i) parliament; ii) government, public sector and local government; iii) justice and anti-corruption authorities; iv) central electoral commission and political parties; v) court of accounts; vi) people's advocate; vii) private sector; viii) civil society and the media (Network for Integrity 2017; Republica Moldova – Parlamentul 2017). The six key objectives of the strategy are as follows (Republica Moldova – Parlamentul 2017):

- discourage involvement in corrupt acts

- recovery of the proceeds of corruption offences

- ethics and integrity to be inculcated in the public, private and non-governmental sectors

- protection of whistleblowers and victims of corruption

- transparency of public institutions, funding of parties and mass media

- education of societies and civil servants

These strategies, along with the international conventions and legal framework, form the guiding principles intended to shape anti- corruption efforts in the republic.

The 2014 banking scandal shook confidence in the Moldovan state to the core, both at home and abroad. Thus, a Priority Reform Action Roadmapwith an implementation timeline was deemed necessary to ensure stability, restore cooperation with the IMF and other development partners, and implement the EU-Moldova Association Agreement (ADEPT, Expert-Grup and LRCM 2016). The roadmap has nine action points related to corruption. An evaluation by a coalition of the ADEPT, Expert-Grup Independent Think-Tank and Legal Resources Centre from Moldova (LRCM) ruled progress towards the nine actions as follows:6a7aeae54709

1.1 Parliament to adopt the set of laws on integrity, including: law on national integrity commission; law on declaration of wealth and interests, which extends the circle of subjects and objects of the declaration of wealth and interests. [Achieved with deficiencies. Thelaw was passed on 25 May 2017 (Teleradio Moldova 2017)].

1.2 Parliament to adopt other related sets of laws on integrity, including: law on integrity in the public sector and the respective amendments to legislative framework related to the law; amendments to the law no. 325 of23.12.2013 on testing the professional integrity based on the principles of constitutionality and introduction of the evaluation of institutional integrity. [Achieved withdeficiencies].

1.3 Parliament to adopt other related laws on delimitation of competences between the institutions with competences fighting corruption, including: law on delimitation of competences between the National Integrity Commission and other authorities on competences to find, pursue and prosecute the wealth from other sources than the one declared; law on delimitation of competences on criminal prosecution between the National Anti-Corruption Centre, ministry of the interior and general's prosecutor office. [In progress – negative].

1.4 Ministry of justice to draft the legislation on incrimination of misuse and misappropriation of EU and international funds which would also tackle the conflict situations in the use of EU and international funds according to the provisions of the Convention on theProtection of the European Communities’ Financial Interests and other international conventions on the matter. [Achieved withoutdeficiencies].

1.5 Ministry of justice to develop anti-corruption initiatives and to further reform the National Anti-Corruption Centre in accordance with the new law on prosecution, the law on the National Integrity Commission and the law on declaration of wealth and interests. [Not launched].

1.6 Ministry of justice to draft special laws on the specialised prosecution: anti-corruption prosecution, fight against organised crime prosecution and the special cause prosecution, in accordance with to the concept of the reform of prosecution and the new law on prosecution. [Achieved with deficiencies].

1.7 National Anti-Corruption Centre to prolong the implementation deadline of the National Anti- Corruption Strategy for 2016. [Achieved without deficiencies].

1.8 National Anti-Corruption Centre to develop the professional integrity electronic file and the sort of electronic evidence. [In progress – positive].

1.9 The National Integrity Commission to implement the online system of submission of declaration of property and personal interests and train its staff. [In progress –positive].

Apart from the roadmap, another process in which the Moldovan authorities were involved until the end of 2016 was the development of a new National Action Plan for the Implementation of the Association Agreement (NAPIAA) 2017-2019, which was approved by the Government on the 28 December 2016 (EaP CSF 2017). At the same time, at the end of 2016, the IMF Board of Directors approved the US$178 million worth macro-financial support programme to Moldova (EaP CSF 2017).new law on prosecution, the law on the National Integrity Commission and the law on declaration of wealth and interests. [Not launched].

International conventions

Moldova is a party to a host of international conventions, treaties and agreements that are intended to guide its fight against corruption. The country is a signatory to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) and Regional Anti-Corruption Initiative – South East Europe (RAI).b6e450edf5a6

In 2016, GRECO called on Moldova to improve and to ensure the effective implementation of anti- corruption legislation with respect to parliamentarians, judges and prosecutors (Council of Europe 2016). It also stated that key problems like the inconsistent application of anti-corruption laws and policies, and the weak capacities and lack of independence of the major institutions in charge of fighting corruption impede overall Moldovan anti-corruption progress (Council of Europe 2016). GRECO is also set to assess,through its compliance procedure, the implementation of the 18 recommendations addressed to the Republic of Moldova in the first half of 2018 (Council of Europe 2016).

Domestic legal framework

The criminal code of Moldova criminalises active and passive bribery, attempted corruption, extortion, money laundering and abuse of office. Sentences for attempted corruption include prison terms of 5 to 12 years and fines of up to US$4,500. Penalties for a public official taking a bribe include prison terms of up to 15 years and a ban from re-entering public service for up to 10 years. Moldova's legislation does not provide an exemption for facilitation payments. Gifts of symbolic values that do not exceed MDL 1,000 or US$56 may not be considered as bribes (UNODC 2016). Legal entities are criminally liable for corruption charges.

The Law on Preventing and CombatingCorruption outlines a set of anti-corruption measures and addresses the protection of human rights and civil society participation in combatting corruption. The Law also prohibits bribery of foreign public officials, trading in influence and protectionism. A number of public financial management regulations are also stipulated under this law:

- transparency and publicity of information on the procurement procedures

- use of objective criteria for decision- making

- guaranteed application of contestation means in cases of violation of established rules or procedures

- establishment of procedures for the accumulation of income and coverage of costs in the budgets at all levels

- efficient norms of accounting, audit and control

- assurance of legal and scope-oriented use of public patrimony, rationally and efficiently

The Law on Public Procurement applies to all contracts of goods exceeding MDL 0.8 million (US$45,000) and all services exceeding MDL 0.1 million (US$5,600). Supplementary procedures apply for contracts involving goods exceeding MDL 2.3 million (US$1,30,000) and services exceeding MDL 90 million (US$5 million) (Turcan Cazaz Law Firm 2016). Public enterprises and private-public partnerships are not subject to the procurement law (UNDP 2016a).

Public officials, such as judges, prosecutors and managers in state-owned companies, are required to declare their income and assets under the Law on Declaration and Control of Income and Ownership. Other relevant laws include the Law on Civil Service, the Law on Preventing and Combating Money Laundering and the Law on Combating Corruption and Protectionism.

Moldova is not on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) list of countries that have been identified as having strategic anti-money laundering (AML) deficiencies (KnowYourCountry 2017). The last mutual evaluation report relating to the implementation of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing standards in Moldova was undertaken by FATF in 2012. According to that evaluation, Moldova was deemed “compliant” for four and “largely compliant” for 18 of the FATF 40+9 recommendations. It was “partially compliant” or “non-compliant” for three of the six core recommendations (KnowYourCountry 2017).

Whistleblowers are not legally protected against recrimination. Under the present Law on Accessto Information, any person has the right to seek, obtain and disseminate official information. The exercise of the right to information may be subject only to the restrictions:

- respecting other people's rights and reputation

- protecting national security or public order as well as public health or morals

However, compliance with the Access to Information Law remains weak, as no state body has the authority to enforce or monitor its implementation. Journalists and civil society organisations regularly report obstruction of their information requests by government agencies (Freedom House 2016b). In a positive step in 2014, the Economic Council of the Prime Minister made basic information about companies registered in Moldova available online through the country’s e-government service, at no cost to users (Freedom House 2016b). However, those seeking information about the founders of companies were required to pay a fee (Freedom House 2016b).

It should be noted that Moldova's anti-corruption legislative framework is ultimately viewed as deficient as a result of inadequate financing and monitoring and a general lack of resources (Business Anti-corruption 2017; Heritage Foundation 2017). The implementation of anti- corruption legislation is further hampered by the lack of professional staff (US Department of State 2017).

Institutional framework

The republic has a number of institutions with a role in the fight against corruption.

The National Anti-Corruption Centre (CNA) is an institution that reports to Moldovan parliament, and its legal framework has been redesigned to only target corruption cases (RAI-SEE 2017).

CNA has the mandate to both prevent andcombat corruption where is occurs (RAI-SEE 2017). It also performs the tasks of the Secretariat of the Monitoring Group for National Anti-Corruption Strategy implementation (RAI-SEE 2017). Among others, CNA is the responsible body for conducting anti-corruption assessments of laws and by-laws, as well as for coordinating corruption risk assessment processes in public institutions (RAI-SEE 2017). The institution undertakes integrity testing of public officials (RAI-SEE 2017). It has been the leading investigator in all the country’s major corruption scandals.

CNA is currently working with selected experts in the following sectors: customs, tax, public procurement, administration and change of ownership of public property, health protection and health insurance, education, agro-food sector, public order, environment as well as local administration (Network for Integrity 2017). The experts are expected to participate in the drafting of sector-based anti-corruption plans (Network for Integrity 2017).

The Centre for Combating Economic Crimes and Corruption (CCECC) was established in 2002 and was the predecessor to the CNA (ACA 2011). It was a central public authority with a distinct legal personality having territorial subdivisions (ACA 2011). In addition, the CCECC coordinated the activities of anti-money laundering supervisory authorities and cooperated with foreign or international organisations dealing with the prevention of money laundering and terrorism financing activities (ACA 2011). A monitoring group was responsible for assessing the performance of all entities that fall under the purview of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (CCECC 2017). The CCECC collated and provided an overview of the data obtained from the various institutions responsible for the implementation of the national anti-corruption strategy and presented it for examination at the sessions of the monitoring group (CCECC 2017). In 2012, it was reformed into the current National Anti-Corruption Centre.

The Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office is a specialised office in charge of leading all the criminal investigations conducted by CAN investigators, although it can also conduct its own criminal investigations (RAI-SEE 2017). An important role among these institutions is vested in the ministry of internal affairs, which is the key coordinating authority in managing the system of domestic affairs bodies (RAI-SEE 2017). The main role in assuring the integrity mechanisms of police is played by the Internal Protection and Anti-Corruption Service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (RAI-SEE 2017).

The National Authority on Integrity (NIA) is a nascent body that came into force in 2016 with the reformation of the erstwhile National Integrity Commission formed in 2012 (EaP CSF 2017; CIS- Legislation 2017). It is tasked with functions such as the control of property and private interests as well as the establishment and imposition of punishments for the violation of the legal regime of property and private interests, conflict of interest, incompatibility and restrictions (CIS- Legislation 2017). However, the pace with which the NIA is being institutionalised is rather discouraging (EaP CSF 2017). A number of authorities continue to hold powers in parallel with those assigned to the NIA: the Supreme Council of Prosecutors, police, National Anti-Corruption Centre and Supreme Council of Magistrates (EaP CSF 2017).

Other stakeholders

Media

According to the 2017 World Press Freedom Index, Moldova scores 30 points and secures a place at 80 out of 130 countries (RSF 2017). A study conducted by Independent Journalism Centre (IJC) indicates a "serious situation for the media in Moldova" (EaP CSF 2017). The most affected areas identified are:

- political context: ownership and extensive involvement of media companies by politicians

- economic environment: the legislation does not provide for limiting the concentration of ownership in media or for accessing commercial advertising by media outlets. Thus, a media company funded by a political party is in the best financial position, though its editorial independence is compromised

- security of media space: the information space of the media is not protected or regulated,thus disseminating manipulative information as tool of influence is a routine activity

- safety of journalists is also at stake

Though the overall media landscape remains polarised, with outlets often used to advance the political or commercial interests of their owners or affiliates, a recent amendment to the broadcasting code passed by parliament requires radio and television companies to disclose the names and stakes of their owners and the names of board members, managers, broadcasters and producers (Freedom House 2016a; Freedom House 2016b). However, media outlets are still concentrated in the hands of oligarchs (Business Anticorruption 2017; Moldovan Politics 2017).

The IJC Monitoring Report notes that the V channels Publika TV and Prime TV (owned by Plahotniuc) disseminate, with few exceptions, the same content in their news stories on major public interest events, and especially on political subjects, presenting facts from a single point of view – favouring the Democratic Party (EaP CSF 2017). They employ several manipulation techniques and have committed infringements of the ethics code including ignorance, generalisation, distortion of the message of the quoted person and truncation of quotes (EaP CSF 2017).

Although explicit forms of state censorship are no longer a common practice in Moldova, the Moldovan press is subject to different forms of pressure that result in the violation of ethical principles and self-censorship (Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung 2017). This can affect the media’s ability to serve as a watchdog over government activity. In this context, it is worth mentioning that, according to the barometer of public opinion issued by the Institute for Public Policies in April 2014, around 61% of the population stated they trust the media; 35% of population trust TV stations the most, 15% the internet, 7% the radio while only 3% identified newspapers as the most trustworthy (Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2017).

Civil society

Moldova's constitution provides for freedom of the press and expression, but authorities do not always respect these rights in practice (Business Anti-corruption 2017). Moldovan civil society has developed considerably in the last decade and their participation in decision-making is increasing (Business Anti-corruption 2017).

Relations between civil society groups and the state have improved since 2009, despite some wariness or even hostility towards NGOs from leading politicians (Freedom House 2016a).

Funding for CSOs is problematic since the vast majority of their funding comes from foreign sources (Bertelsmann-Stiftung 2016).

The government upholds freedom of assembly, as witnessed by several opposition parties and civic groups, particularly the Dignity and Truth platform, organising several anti-government and anti- corruption protests during 2015 without obstruction from the authorities (Freedom House 2016a).

Various CSOs pursue the fight against corruption in Moldova. These include:

- Transparency International Moldova (TI- Moldova). TI-Moldova is a strong voice for anti- corruption reform, publishing papers on the state of corruption in the country as well as taking part in shaping the future anti-corruption policies of the republic. It has recently supported the MTender pilot that is set to reform procurement processes (WNISEF 2017). It was also the first to draw attention to the draft law that would allow the legalisation of illegally acquired capital (Transparency International Moldova 2017b). TI-Moldova also undertakes valuable monitoring reviews of the process of resetting the anti-corruption system (EaP CSF 2017).

- Centrul de analiză și prevenire a corupției (Centre for the Analysis and Prevention of Corruption). The centre seeks to reduce corruption in the country to a level that does not affect citizens’ rights and freedoms. Enhancing awareness of the danger to the state posed by corruption. Studying the level of corruption penetration in society and the state are other areas of their work. They champion the enhancement of the level of transparency in the activity of state and political institutions.

Successful social accountability initiatives in neighbouring countries

The scourge of corruption does not plague Moldova alone. Civil society groups in some of the country’s neighbours have used social accountability as a mechanism to prevent and fight cases of corruption. A study by Caddy, Peixoto and McNeil (2007) found various social accountability cases which achieved a notable degree of success.

- Assessment of inefficiently used public funds in public procurement in the Czech Republic. The aim was to assess the losses caused by inefficiency and lack of transparency in the awarding of public contracts. An analysis was prepared based on data from the ministry of finance and the Czech statistics office as well as the findings of the supreme audit court. It was found that expenditures for the purchase of goods and services by central government amounts to 4.3% of the GDP. It was estimated that 14.7% of this funding was used inefficiently.

- Online dialogue for the participatory budget of Berlin-Lichtenberg in Germany. The aim was to foster an agreement in policy decisions, achieve effective and fair budgeting, induce transparency and comprehension in financial matters and generate a lively discussion while devising pragmatic solutions. It resulted in 4,000 people being involved in just the pilot session. The local council passed 37 of the 42 proposed budget and policy amendments. The prioritised list of 42 proposals was the result of cross-media dialogue on hundreds of individual submissions. The main impact was enhanced accountability of local government.

- Quarterly bulletin of public finance in Poland. The aim was to gain up-to-date information on public finance in Poland and assess Poland’s public finance in terms of international transparency standards. The bulletin fostered informal partnerships in civil society and enhanced government accountability in general.

- Hameelinna participation tools in Finland. The aim was to improve the quality of public services by strengthening citizens’ confidence in local politics, enhancing citizen participation, increasing communication between local government and citizens, improving the standard of living, especially in disadvantaged districts and enhancing solidarity. Though the project is long-term, some of its impacts include a more citizen-oriented and transparent local government, better communication between citizens and local government, and more networking between civil society actors.

Role of external development actors

Moldova does not stand alone in its fight against corruption; external partners have a significant role to play, a few examples of which are as follows:

- Sweden provided core support for East Europe Foundation Moldova (EEF-M) activities in Moldova to the tune of US$3.3 million. The main areas covered were civil society participation and oversight, promotion of independence and quality of media reporting, free and fair elections, building sustainable communities and local democracy, facilitating community organising for local development initiatives, social entrepreneurship development, Youth banks and protection of rights of marginalised and underrepresented groups (EEF2017).

- The Romanian government pledged to lend Moldova €150 million (US$179 million) to push through anti-corruption reforms after the nation was rocked by a massive scandal in 2015 (Euractiv 2016).

- The Canada Fund for Local Initiatives in the Republic of Moldova supports small projects proposed and implemented by local NGOs and other community-based organisations that address the identified needs of local communities. Those that seek to champion human rights, inclusive and accountable governance, democracy, peaceful pluralism, and respect for diversity, as well as support inclusive and green economic growth while promoting peace and security, are free to apply (Embassy of Canada to Romania, Bulgaria and the Republic of Moldova 2017).

- The Netherlands provides official development assistance (ODA) based on a long-term bilateral cooperation framework. Most of the aid is provided through NGOs. It has three assistance programmes: good governance, small embassy projects in the field of poverty reduction, and World Bank Health Investment Fund for improving the healthcare sector (Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Ukraine and Moldova 2017).

- The Embassy of Finland recently invited Moldovan NGOs to apply to the Fund for Local Cooperation (FLC) in the fields of poverty reduction, environmentally, economically and socially sustainable development, protection of human rights, promotion of democracy and good governance, and civil society strengthening (FundsforNGOs 2017). The awards amounts ranged from €25,000 to €50,000 (US$30,000 to US$60,000) (FundsforNGOs 2017).

Finally, UNDP provides support to multiple reformmeasures in Moldova. A few striking projects aimed at corruption control currently being sponsored by UNDP are listed below:

- Strengthening the corruption prevention and analysis functions of the National Anti- Corruption Centre (CNA): endow the CNA Prevention Directorate with modern equipment and specialised software; support CNA to elaborate and implement a new national anti- corruption strategy and action plan, assess corruption risks and development of integrity plans in vulnerable sectors; develop a platform for cooperation between CNA and civil society while supporting initiatives that promote youth awareness and engagement in anti-corruption; strengthen CNA´s capacity to perform corruption analysis as per national and international strategic documents.

- Construction of the jointly operated border crossing point at Palanca on the territory of the Republic of Moldova: the objective is “safer and more open borders” between Ukraine and Moldova. The expected long-term impact is to contribute to the facilitation of trade and migration flows between the two countries. However, corruption risk reduction is also an aspiration.

- Enhancing democracy in Moldova through inclusive and transparent elections: the project, in collaboration with the Central Electoral Commission, Centre for Continuous Electoral Training, Agency of Public Services (Civil Status Service, SE “Cadastru”, SE “Registry”), E-Government Centre, NGOs and other stakeholders, shall seek to achieve a more accurate state register of voters (SRV), enhancing the inclusiveness of the electoral process through developing a remote voting tool, and supporting legal reform in elections to erase ambiguities and respond to the technical developments.

- Establish the Moldova Social Innovation Hub (MiLab): establish sustainable mechanisms and processes for promoting an active participation of people in the development of their country and communities.

- Procurement support services to the ministry of health: to strengthen the capacity of the ministry of health to ensure transparency, accountability and effectiveness of the public procurement of medicines, and to create a coherent pharmaceutical policy.

- Policy analysis, research, and support to state chancellery and implementation of 2030 agenda: support central public administration reform and help the government to develop and contextualise a 2030 agenda at the national level.

- Strengthening the Social Cohesion and Reconciliation (SCORE) Index: define and assess levels of social cohesion in Moldova with an eye to adjusting UN interventions in the country to better support the strengthening of social cohesion.

- Strengthening capacities at the ministry of internal affairs (MIA) and its internal subdivisions for the effective implementation of the sector reform agenda: enhance the institutional, operational and functional capacities of the MIA.

- Strengthening parliamentary governance in Moldova: enhance the capacity of the parliament to timely review draft laws and their compliance with international treaties and EU legislation, as well as strengthen the cooperation between the parliament and government to ensure a transparent, participatory and gender-sensitive law-making process.

- Strengthening technical capacities of the National Institution for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights.

- Strengthening the National Statistical System: to help the government to advance on its European integration agenda on harmonising of official statistics with EU and international standards.

- Support to justice sector reform: objective of increasing the independence, accountability, impartiality, efficiency and transparency of the justice system as a prerequisite for sustainable development.

- Support to police reform in the Republic of Moldova.

- Defect from one party to another (Transparency International Moldova 2017a).

- On 16 December 2016, the parliament adopted in first reading the Draft Law no. 452 on fiscal stimulation and capital liberalisation and the Draft Law no. 451 on amendments and additions to certain legislative acts in force. The acts were passed in the first reading in an unprecedented rush, breaching the rules of legislative drafting and disrespecting the norms of transparency in the decision-making process. The major risk being that these legal acts would have allowed any person, including public officials, to declare and legalise any assets for a fee of 2% of their value, without declaring the origin of such assets. Allowing any physical person or legal entity to legalise their capital and assets without an investigation of their origin would clearly favour those whose assets had a criminal origin, including from corruption and money laundering (EaP CSF 2017). Transparency International Moldova (TI-Moldova) was the first to bring this draft law to the attention of all the development partners in the country by issuing position papers and organising public appeals as well as garnering support among other NGOs (Transparency International 2017b). TI-Moldova drew the attention of the National Bank of Moldova and the Ministry of Finance to the inadmissibility of allowing the legalisation of illegally acquired capital, under the cover of laws adopted with deviations from the constitutional provisions of the Leanca, Gaburici and Filip governments (Transparency International Moldova 2017b). Later, the Independent Analytical Centre “Expert-Grup”, Legal Resources Centre from Moldova, the Institute for European Policies and Reforms and many other NGOs stated on 19 December 2016: “Besides prohibiting the investigation of the origin of civil servants’ properties, the liberalisation of capital forbids their punishment for the previous failure to declare these properties, thus discouraging the officials who have honestly declared their properties. This situation is at odds with the recent efforts to combat corruption in the public sector. Capital liberalisation initiative contradicts the ‘Integrity Package’ voted by the Parliament in the summer of 2016, which was part of the Priority Reform Action Roadmap established by the Republic of Moldova and the European Union. Capital amnesty without the possibility of investigation creates major risks of corruption perpetuation or increase in the future as well.” Following the IMF mission review in Chisinau from in February 2017, the mentioned bills were withdrawn from the parliament (EaP CSF 2017).

- On 19 June 2017, the Venice Commission and the Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights of the OSCE issued a negative review of a draft electoral law in Moldova. The government says the draft bill is the result of parliamentary consensus. In fact, it is said to have been designed to keep the Democratic Party of Moldova (PDM) and its unpopular leader, Vlad Plahotniuc, in power after next year’s parliamentary elections (Pieńkowski 2017). The bill introducing a mixed electoral system was approved by lawmakers and signed into law by Dodon in July despite mass protests in Chisinau and criticism from the EU and the United States. The new legislation provides for half of the lawmakers to be elected on party lists and another half in individual constituencies (RadioFreeEurope 2017a).

- Moldova's previous scores are as follows: 2012 – 36 points; 2013 and 2014 – 35 points; and 2015 – 33 points (Vlas 2017a).

- Indicates rank of country among all other countries in the world, where 0 corresponds to lowest rank, and 100 corresponds to the highest rank (The World Bank 2016).

- The overall country risk score is a combined and weighted score of four domains – business interactions with the government, anti-bribery laws and enforcement, government and civil service transparency and capacity for civil society oversight, including the role of the media – as well as nine subdomains (TRACE Matrix 2017).

- Economies are ranked on their ease of doing business, from 1–190. A high ease of doing business ranking means the regulatory environment is more conducive to the starting and operation of a local firm (Doing Business 2017).

- 1=most free, 7=least free (Freedom House 2016a).

- The Russian Laundromat was a scheme to move US$20–80 billion out of Russia from 2010 to 2014 through a network of global banks, many of them in Moldova and Latvia (OCCRP 2014).

- The Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) is a Council of Europe body that aims to improve the capacity of its members to fight corruption by monitoring their compliance with the organisation’s anti-corruption standards. It helps states to identify deficiencies in national anti-corruption policies, prompting the necessary legislative, institutional and practical reforms. Currently it comprises the 47 Council of Europe member states, Belarus and the United States of America (Council of Europe 2016).