Lobbying brings many benefits to the deliberative process: it can help governments obtain policy decisions that optimise the management of public goods; it is critical to democratic processes (when done in an inclusive manner it broadens public participation); and it can improve government accountability for policy choices. However, because lobbying enables stakeholders to influence policy it also poses risks – namely, that some stakeholders will get more access and more influence than others. When there is a perception that systems and structures for lobbying exclude certain stakeholders, public confidence in policymakers, in the decision-making process, and in affected policies, can be eroded.

Decision-making around climate action99d0c855f445 faces precisely such an erosion of confidence. Critics of the global deliberative process have identified numerous instances of certain stakeholders, especially energy corporations, getting more access to decision makers, and therefore obtaining superior opportunities to influence climate policy. Inequality in access has been documented around peak global events such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP), and around policymaking that has climatic consequences in countries as diverse as Australia, France, Ghana, Tanzania, and USA.90e8eec9d45f Indeed, as the earth heats up and climate policy development gets more feverish, critics fear that exclusionary lobbying will jeopardise the targets of the UNFCCC’s Paris Agreement specifically8e49e34546d2 and a transition to low-carbon societies and economies generally.97fc8bf06d9c

To the frustration of critics of climate policymaking, although legal frameworks have been effective at regulating some aspects of lobbying, they have proved ineffective at preventing exclusion or promoting inclusion. Given the ongoing corruption scandals connected to lobbying, as described in this paper, it is clear that anti-corruption laws have also proved to be insufficient on their own as either a deterrent to unethical or ‘corrupt’ lobbying, or as an instrument to sanction or prosecute breaches of lobbying rules. Thus, while a chorus of criticism about decision-making around climate action mounts, the corporations that continue to lobby and the policymakers with whom they engage, face few – if any – legal or reputational consequences.

Incentives to lobby, and the pressure on policymakers to make decisions around climate policy, are exacerbated by the fact that climate action is big business. In 2018, investments in climate change interventions were worth US$546 billion, of which 59% came from private sources and 41% from public sources.7b11f9d2d488 In 2019, climate-related development finance (CRDF)d1d2e657068a – finance channelled to international development programmes – totalled US$79.6 billion.ab34ece19d92

This paper is concerned with corruption risks in lobbying around climate interventions in the international development sector. It is worth noting that lobbying around climate change – that is, attempted policy influence – is not only focused on profits. Lobbying by civil society organisations (CSOs), community groups, research organisations, scholars, and even donors themselves – as well as businesses adopting triple bottom line principles53d2ee5dfa0d – is more likely to be motivated by the ecological and social consequences of global warming than by profit seeking.

It is also worth noting that lobbying is just one activity within broader advocacy. Advocacy goes beyond influencing policy to aim for ‘…sustainable changes in public and political arenas, including awareness raising, litigation (legal actions) and public education, as well as building networks, relationships and capacity.’a87ade29de56 These types of non-lobbying advocacy work are a prominent feature of both international development and climate action. Nevertheless, it is only anti-corruption tools related to lobbying, and not advocacy more broadly, that are addressed in this paper.

Analysis and recommendations for international development presented in this paper are relevant for lobbying in general, but for three reasons most of the examples and case studies relate to energy. First, the vast majority of global investment in mitigation – 89% – is channelled to renewable energy (64.4% or US$322 billion) or low-carbon transport (24.4% or $122b).1a9fc438a2f3 The energy sector is also the largest recipient of CRDF: US$17.6 billion, or 22.1% of the total.d0c8d8580560 Second, and as is discussed in this paper, most of the criticism of exclusionary lobbying focuses on oil and gas producers. Our own focus on the energy sector is therefore partly to respond to these specific, sector-related, concerns. Third, it is not clear that lobbying practices, corruption risks, or anti-corruption measures for lobbying, differ between sectors. We therefore focus on the energy sector because of its importance for climate change, because of the abundant examples that can be used to highlight analytical points, and to partly address energy-specific concerns about lobbying, corruption and investments in climate action.

This paper draws on recent literature and cases of exclusion from policymaking to analyse the problem of lobbying around climate action. It focuses on international development, a sector where inclusion and inclusive processes are fundamental goals. It argues that structural and conceptual limitations in lobbying and anti-corruption laws make them insufficient to counter exclusionary practices or promote inclusion in international development. Therefore, they should not be the only tools relied on to achieve these goals.

We argue that the widely accepted developmental goal of inclusion – an aspiration captured by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – can bring focus to donors’ efforts to reduce exclusionary lobbying. We also argue that well-established guidance on managing engagement around procurement within international development can be harnessed to regulate lobbying. Our approach builds on existing principles, knowledge, tools and skills in international development, which avoids wasting effort, resources and time, especially given the imperative to cut emissions.

This paper commences by introducing the reality of lobbying and what its critics have to say, including the reservations that exist about standard conceptions of ‘corruption’ and their usefulness for addressing exclusionary lobbying. We examine the financial stakes of climate action and why, given the money involved, prominent lobbying should be expected. Stakeholders with an interest in lobbying are identified, along with their techniques and avenues of influences, with additional elaboration and identification relevant to international development. The paper then shows a way forward for development partners trying to forestall exclusionary lobbying and promote inclusivity in policymaking. It details measures such as adapting procurement to managing lobbying-related engagement, and concludes by reimagining how a documented case of exclusion around energy-related policymaking in Tanzania could have been managed differently to produce more inclusive outcomes.

The final section, Recommendations for Donors, draws on the report’s analysis to present a series of recommendations that build on each other. The recommendations focus on what donors can do, in addition to using legal tools, to help reduce exclusionary lobbying and to improve inclusive practices around CRDF. This section repeats some of the analysis from the main body of the report and can therefore be read as a stand-alone section.

What is lobbying and why is it important?

There are many definitions of lobbying, some of them very detailed in law. The OECD considers lobbying to be ‘the oral or written communication with a public official to influence legislation, policy or administrative decisions’, with ‘public official’ defined as including ‘…civil and public servants, employees and holders of public office in the executive and legislative branches, whether elected or appointed.’f8c633e82e92 An alternative definition that avoids the need to define ‘public official’ is by Transparency International: ‘Any activity carried out to influence a government or institution’s policies and decisions in favour of a specific cause or outcome.’6cf528c49bbb

In some cases, such as lobbying by the private sector, the ‘specific outcome’ sought may be higher profits. In other cases, rather than seek a direct financial benefit, businesses may desire an ongoing influence over policy and decision-making as part of their triple bottom line principles. By contrast, lobbying by CSOs and community groups is most likely to be motivated by non-financial imperatives, such as climate change or other environmental concerns, healthcare, education, human rights, or animal welfare.

Lobbying may be undertaken by third party, professional lobbyists paid to negotiate and influence policy on behalf of clients. Larger companies and organisations may have in-house employees who lobby government – for example, in government relations units that perform a similar function to third-party lobbyists. Organisations lacking such specialist staff may lobby government using senior executives and managers. In the case of community groups, community representatives and leaders may perform this role.20a037dce017

The advantage of Transparency International’s definition of lobbying is that instead of requiring a list of individuals who come under the definition of ‘public official’ – a list that may fail to keep up with evolutions in governments, public sectors and other organisations that make policy decisions over public goods – it focuses on the entities targeted by lobbying. These entities include governments and other institutions, such as multilateral organisations like UN agencies or development banks, that have a decision-making role in climate action.

Another advantage of Transparency International’s definition is that by focusing on ‘any activity carried out to influence’, it dispenses with the need to define specific activities that comprise lobbying. Efforts to control lobbying invariably adopt laws and codes that include a list of prohibited, regulated or notifiable activities. However, these can struggle to keep up with evolutions in communications and contacts between stakeholders and decision makers.

Lobbying is important because it creates a way for interest groups to have input into the content and making of policies and laws. Such participation is a fundamental element of democracies, where ‘the people’ expect to be able to communicate their policy preferences to policymakers. Regulated lobbying creates a record of opinions expressed, the process used to obtain them, and whether they were listened to. Dávid-Barrett93e08e3d5707 argues that ‘Done well, lobbying ensures that groups with relevant expertise and those who will be affected by a policy can provide useful inputs. It can help ensure that public policy is made and public money spent in ways that serve the public interest’. That is, deliberative processes facilitated through lobbying also facilitate accountability. Box 1 details an example of lobbying best practice.

Box 1: An example of ‘good’ lobbying around natural resource governance

Ghana’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (GHEITI) has a multistakeholder group (MSG) that currently includes representatives from:

- civil society – Publish What You Pay Ghana; Wassa Association of Communities Affected by Mining (WACAM), a 20-year old environment human rights non-governmental organisation (NGO) focused on communities affected by mining; and the Integrated Social Development Centre (ISODEC), a rights-based public policy research and advocacy NGO

- business (three oil and gas companies; one mining company)

- the state-owned petroleum corporation

- several state commissions and ministries with responsibilities for energy

- subnational government representatives from regions that host energy developments.

In 2016, when new legislation regarding forthcoming oil revenues was being considered by parliament, the MSG lobbied parliament on Ghana’s proposed Petroleum Revenue Management Act (2011) and the Minerals Development Fund Act (2014), as well as the pending Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Bill. Ghana’s success at implementing policy reform and achieving transparency over oil and gas revenue has been largely accredited to the MSG’s work.GHEITI received the 2016 Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) Chair’s Award for its efforts to shape national legislation and policy.

Disquiet about lobbying

Notwithstanding the usefulness of lobbying for the deliberative process, there is disquiet by scholars, CSOs, anti-corruption agencies, research organisations, journalists, and politicians that any benefits from lobbying – including for climate action – are being undermined by three issues related to corruption:81ebf8ca1980

- Incentives: Sometimes parties use incentives as part of their lobbying to influence public officials’ decision-making, giving them an unfair advantage – for example,gifts, travel, entertainment, bribes, kickbacks, jobs, or donations to political parties. Laws, regulations and codes of conduct around lobbying, as well as anti-corruption laws themselves, have been introduced in many jurisdictions to explicitly prohibit incentives in the public sector.

- Transparency: When there is lack of transparency around lobbying, the lobbying parties and those who are being lobbied are able to keep communication and contacts secret, causing opacity in policymaking that is antithetical to deliberative process ideals. Lack of transparency allows ‘the lobbied’ to remain unaccountable, because the public does not know who influenced their decisions and actions. Lobbying and anti-corruption laws have been introduced in many jurisdictions to promote transparency by making obligatory such things as registers of meetings and attendees, online publication of official diaries, requirements to maintain records of oral and written communications, and registers of third-party lobbyists.

- Exclusion: Some parties gain more opportunities for influence, resulting in the exclusion of other voices, ideas and interests. Such a situation is antithetical to democratic ideals. Professional lobbyists earn their fees by guaranteeing their clients special access to decision makers. Yet, such fees are outside the budget of most non-corporate actors, leading to an imbalance of influence that benefits those with wealth. Exclusion and special access are often facilitated by hiring former politicians or by exploiting personal contacts based on shared social status and networks. Such practices give rise to criticism, including privileges of the ‘old boys network’.

Laws and standards on lobbying, including anti-corruption laws, have been introduced in many jurisdictions to address (1) and (2).9bc13fb99a0c The OECD also produces guidance on lobbying through its Anti-Bribery Convention, Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, and Recommendation for Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service.c0b33ce61834 Notwithstanding these rules and guidance, research shows that regulation has not succeeded in eliminating unfair access and influence to policymakers, although they may have improved transparency and overall anti-corruption awareness.11677d68124e

The greatest concern is reserved for issue (3): exclusion. Disquiet about exclusionary lobbying practices in the climate sector focuses on the risk these practices pose to mitigation initiatives, as well as to a just transition whereby a transition away from fossil fuels to renewables brings material benefits such as decent jobs and liveable communities to ordinary citizens.afb147465963 Box 2 describes examples of lobbying relevant to climate action that illustrate aspects of inequality or exclusion.

Box 2: Examples of inequality or exclusion around lobbying on climate action

1. Coal mining in New South Wales (NSW), Australia: Journalists researched ministerial meeting diaries (which are made public under lobbying regulations) to identify levels of access by different stakeholders in NSW) – coal accounts for 80% of the value of NSW mineral production. Over a 235-week period from 2014 to 2018, the environmental NGO with the most access was the Lock the Gate Alliance, which campaigns against coal and gas developments in a specific geographic area. It had a total of 19 meetings over the period – an average of one every 62 business days. By contrast, the resource industry as a whole had 188 meetings with NSW ministers, about one every six business days (ten times more than the Lock the Gate Alliance).

2. Huge wealth employed against mitigation measures in the USA: Research into the financial resources of 91 climate change ‘countermovement’ organisations (eg, advocacy groups, think tanks and trade associations) in the USA estimated that the country has a combined annual income of US$900 million, funded by 140 different foundations. This wealth is used to fund lobbying against policies seeking to mitigate global warming.

3. Payment for ‘visibility’ at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26): Equinor, Norway’s giant state oil firm, lobbied the UK government’s COP26 Unit to give it ‘visibility’ in return for sponsoring the conference. Equinor’s representative asked ‘If I was to ask you – ball park – how much money you would like from us, for what, and with what visibility for us, what would you say?’ The company was hoping for some level of exclusivity whereby money bought it visibility that other organisations would not receive. Equinor’s communications with the COP26 Unit were not required to be automatically disclosed under UK lobbying regulations; the incident came to light through a Freedom of Information request from a CSO.

4. Privileged access to delegates at the 2019 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP25): In preparation for COP25 in 2019, the Spanish government asked the 35 biggest companies listed on the Spanish stock exchange to contribute €2 million (US$2.3 million) each, claiming it was raising money to host the talks in Madrid. Spain’s ‘single most polluting company, coal and gas utility Endesa’ was one of the corporations that took up the offer (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2019). The government later offered tax breaks on these contributions suggesting that, far from paying for COP25, the contributions were a government strategy to secure access to UN Framework Convention on Climate Change delegates for its largest corporations en masse. Companies like Endesa were able to set up a stall in COP25’s civil society ‘green zone’ (the UNFCCC considers businesses to be CSOs). Other businesses and CSOs were invited to establish stalls in the green zone and also had access. However, the ‘contributions’ justification effectively created privileged, state-sponsored, opportunities for lobbying by Spanish corporations.

5. French Minister outmanoeuvred by lobbyists: In 2018, Nicolas Hulot, France’s Environment Minister resigned because he felt unable to fulfil his mandate. In part, this was because of the challenges he faced getting new policies and programmes accepted and adopted within his own government. But Hulot also explicitly mentioned the power of lobby groups to subvert agendas and discussions. Albeit a different issue to climate change, he gave the example of a meeting where he discovered lobbyists for hunting present at a meeting to which they had not been invited, raising the question of who controlled inclusion/exclusion in policy discussions within the Ministry.

What the examples in Box 2 have in common is privileged access to decision makers by some lobbying parties, but not others. What they also share is the apparent lack of any breach of anti-corruption or lobbying law or standards. In these examples, Australian, US, British, Spanish, and French lobbying rules permitted these situations, and no corruption offences had been committed. To the chagrin of observers, this meant that there was never any basis for an ethics investigation into the involved parties, let alone legal charges.

These examples also show that ‘exclusion’ does not always mean that non-corporate stakeholders get totally ignored. Rather, while CSOs or community groups may have opportunities to lobby, their efforts are overwhelmed, outnumbered and ‘out-resourced’ by corporate lobbying, resulting in a non-inclusive process. Sometimes certain stakeholders are ignored. For example, Tanzania’s burgeoning natural gas sector saw successful lobbying on the development of new laws by multinational energy companies, local businesses and the local EITI chapter, but citizens and national CSOs felt bypassed in the lawmaking process.24da21b345dc

Exclusionary practices in lobbying are not just a problem for climate action. Research confirms that, despite increasing regulation of lobbying, inequalities of access continue to exist in democratic systems and are eroding public trust in democracy and the efficacy of civic participation.d5a6e9714962 Furthermore, lobbying and anti-corruption regulations established to control exclusionary practices seem unable to fix the problem.

Warrenb53d5ecbe466 argues that this ‘disconnect’ between expectations of inclusivity and the suitability of laws to respond to exclusion, is the result of how corruption is commonly conceptualised. He argues that standard definitions of corruption within democracies fail to address inequalities of access, because they have the wrong emphasis:

With few exceptions, political corruption has been conceived as departures by public officials from public rules, norms, and laws for the sake of private gain. Such a conception works well within bureaucratic contexts with well-defined offices, purposes, and norms of conduct. But it inadequately identifies corruption in political contexts, that is, the processes of contestation through which common purposes, norms, and rules are created.22f399a036d4

Warren argues that political corruption in democracy ‘…is a violation of the norm of equal inclusion of all affected by a collectivity (unjustifiable exclusion)’. He goes on to argue that:

Exclusion (a) is a necessary but not sufficient condition for corruption. In addition, two other conditions are necessary:

- A duplicity condition with regard to the norm of inclusion: The excluded have a claim to inclusion that is both recognized and violated by the corrupt.

- A benefit/harm condition with regard to the consequences of exclusion: the exclusion normally benefits those included within a relationship and harms at least some of those excludeda18b4d8cf130

Warren’s conceptualisation of political corruption remains apt today in the way it captures the concerns of climate activists. First, the activists suffer exclusion in that their degree of access is unequal. Second, there is duplicity because policymakers allow climate activists (such as environmental groups) some access, recognising their right and importance, but simultaneously allow far greater access to corporate interests. Third, there is a benefit/harm condition: corporate interests make money or get better opportunities to adapt to climate change; excluded stakeholders are left to cope with far less government support. As is discussed in the section ‘Tools for donors to manage lobbying’, when combined with some standard anti-corruption strategies already practised by donors, Warren’s conceptual approach shows a way forward for managing lobbying around climate action within international development.

Limitations of a legal approach to lobbying

As noted, governments’ responses to corruption concerns around lobbying has frequently been to regulate it through law. But where concerns around lobbying have persisted, the response has been to further tighten regulations and eliminate perceived loopholes around illegal incentives, inadequate transparency and unequal access. There appears to have been no consideration of the limitations of an approach based primarily on lobbying laws.

The bureaucratic approach of more regulation is exemplified by the work of NSW’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). In 2010, following widespread concern that state-level lobbying was fuelling practices that undermined public confidence in government, ICAC held an investigation into lobbying. It released a report with 17 recommendations, including the introduction of a dedicated lobbying law.9a5f2410f2cf Ten years later, in 2020, ICAC held a second investigation to ascertain the impact of the new law and associated regulations. This decision was taken against the backdrop of a perceived expansion in lobbying, several lobbying-related corruption scandals involving senior political figures, and widespread commentary that lobbying was, again, eroding confidence in government.5cad132700a7

The second report contains 29 recommendations to tighten various laws, codes, standards, and procedures to eliminate loopholes that hinder transparency. Recommended reforms include some obvious prohibitions against gifts or money changing hands, favouritism in terms of public officials being given jobs or appointments post-government employment, as well as a recommendation that public officials should not engage in favouritism. The report also recommends an obligation for public officials ‘to act in the public interest and not for any extraneous purpose‘.3a67de5da396 ICAC’s recommendations were not aimed at managing global public goods such as a stable climate secured through capped carbon emissions.9f2b59efbcd0 However, the principle of ‘public interest’ is at the core of criticisms of lobbying.

If implemented, ICAC’s recommendations are likely to reduce corruption risks in lobbying. However, its bureaucratic legalistic approach is likely to face some limitations, especially around exclusion.

First, law and regulatory reform is often a slow process, and must always play ‘catch up’ in response to the evolution of techniques, and as stakeholders’ and society’s expectations evolve. Unfortunately, trends take time to emerge and have effect – that is, the need, urgency and appetite for reform may not be apparent until a scandal occurs or there is a crisis. ICAC waited ten years before it revisited NSW’s initial lobbying law and this occurred because of a perceived loss of confidence in government. Furthermore, drafting and implementing a new state lobbying code based on ICAC’s most recent recommendations – should NSW Parliament decide to accept them – could take several years.

Second, laws to prevent corruption in lobbying on their own, do not counteract economic and political structures that facilitate exclusion and unequal access. How could they? Inequality of access is partly caused by unequal resources, and lobbying laws cannot change this. Creating quotas of meetings or other events with different stakeholders, or of communications, may be theoretically possible and address the need for balance in access. However, this opens many questions around: the quality of information that could be obtained via such regulated processes; how the most urgent issues could be identified and addressed; and politicians’ need for discretion over their meetings. No politician wants a bureaucrat to dictate their agenda, a measure that would also undermine democratic ideals – recall French Environment Minister, Nicolas Hulot, who resigned partly because of his lack of control over invitees to meetings (see Box 2, no. 5). Even if opportunities for influencing policy are created, this still requires motivated and sufficiently resourced stakeholders who want to engage, (although, this is unlikely to be a problem in climate debates). Inequality may also only become apparent over time – recall The Guardian’s research into ministerial diaries over a 235-week period in NSW (see Box 2, no. 1) – and lobbying laws seem ill-suited to prescribe access based on a retrospective understanding of historical patterns.

Third, current bureaucratic methods of generating transparency appear to rely on CSOs, the media or researchers to monitor data about lobbying to identify potential breaches. For example, it was Culture Unstained’s investigation into lobbying around COP26 that brought to light Equinor’s email offering to trade money for visibility (see Box 2, no. 3), and The Guardian’s study of ministerial diaries that showed the imbalance in stakeholder access in NSW – not any government ‘red flag’ system. This creates a situation in which CSOs or opposition political parties bear the burden of identifying unequal access and hoping the government launches an ethics investigation, rather than such an accountability activity being an institutionalised part of government itself.

Potential for anti-corruption laws to limit exclusion

It is useful to return to ICAC’s recommendation from its 2021 lobbying inquiries that public officials should be obligated to ‘act in the public interest.’ This obligation is central to critics’ demands that climate debates should be shaped by the public interest, which they argue means the fastest possible reduction in greenhouse gases (GHGs), preferably via a just transition.

In addition to its public inquiries into corruption-related issues, such as its lobbying inquiry, ICAC investigates allegations of corruption through a commission of inquiry that identifies evidence and investigates findings of individuals’ corrupt conduct.bc496b474285 Two of its investigations show that anti-corruption laws – quite separately from lobbying laws – could potentially be used to counter unequal stakeholder consultation (assuming the relevant anti-corruption law has provisions that allow this). The investigations partly focused on public officials’ exclusion of certain stakeholders’ advice and interests in their decision-making.

- Operation Atlas

From 2006 to 2008, ICAC investigated allegations of corruption in the planning unit of a local government responsible for recommending and advising on urban development.ce48398d10e4 The allegations focused on close personal relationships and unmanaged conflicts of interest between a municipal planner and a private developer promoting a US$100 million mixed residential–commercial building project. Part of the investigation focused on the pro-business/pro-development attitudes of the local government’s general manager, including him turning a blind eye to the planner–developer relationship; encouraging the planning unit to approve developments, even when breaching government standards; and not seeking advice about the specific project. The general manager deliberately failed to obtain input from certain stakeholders to ensure his preferred outcome: the project going ahead.

ICAC found the general manager prevented consultation with elected officials, who according to policy should have been consulted, because he thought they would veto the project. It also found he ignored or failed to properly consider expert technical planning advice available within government. Ultimately, ICAC found that the general manager engaged in conduct conducive to corruption involving the ‘partial exercise of official functions’ [emphasis added], which breached the NSW anti-corruption law. The general manager resigned. His case was not referred to state prosecutors for prosecution in a criminal court.b23b19fcb52d - Operation Avon

From 2017 to 2020, ICAC investigated allegations that public officials in the NSW Department of Primary Industries – Water, engaged in corrupt conduct. Specifically, that they: gave confidential information to a select group of farm irrigators; managed river water in a way that favoured these irrigators; neglected to investigate or prosecute compliance breaches (water theft); and encouraged farmers to steal water despite an embargo being in place due to drought conditions. That is, the officials gave privileged access to irrigators and were not inclusive of all stakeholders’ interests.

ICAC did not make findings of corrupt conduct against any official, concluding that their decisions were not made for corrupt reasons (such as personal gain), and they were following departmental policy and practice to give equal weight to environmental, social and economic considerations. The department’s officials had emphasised avoiding further negative socio-economic impacts on irrigators, whose water entitlements were being cut due to drought. ICAC found this triple bottom line approach to be an ‘improper balancing’ of environmental and industry interests. It argued that, under state law, protection of the environment should have been the priority and should not have been balanced with social or financial concerns. ICAC found that the department’s approach breached the government’s own principles for water management, stating …

‘… protection of the environment and basic landholder rights must not be prejudiced by any other right.’

In other words, ICAC found that public officials had privileged the interests of certain stakeholders, and excluded the interests of others, including the water needs of the environment itself.e8c8c7218a88

Despite limitations in legal approaches to exclusionary lobbying, introducing lobbying laws and reforming them periodically can be a helpful strategy. Research shows that legalised lobbying can reduce corrupt methods of influencing policy,b0ec028985a3 and therefore, from a purely anti-corruption perspective, lobbying laws and regulations are important. Regulatory frameworks for lobbying can also assist donors and recipients to control corruption, regulate influence over development policy and programmes, and create a baseline of standards and regulation around incentives and transparency. Nevertheless, laws and regulation alone are likely to be insufficient for addressing exclusionary lobbying.

Lobbying and climate action: the financial stakes

Climate action and related lobbying have implications that go beyond reducing emissions, to the specific details of policies on sectors such as energy, mining, transport, agriculture, and forestry. Not all stakeholders take this into account. A representative from an NGO campaigning against the negative human, environmental and political impacts of transnational corporations, stated that Madrid’s COP25 was ‘meant to come up with policies to rein in the consumption and burning of fossil fuels‘ and criticised access given to companies like Endesa (see Box 2, no. 4): ‘It’s important to draw a distinction between policymaking and policy implementation. In the case of climate change, will these utilities [like Endesa] have to be involved in the implementation of policy? Absolutely. But why should they be writing the rules?‘4c085f015350

This view lacks nuance. ‘Writing the rules’ around climate policy may once have focused primarily on limiting the consumption and burning of fossil fuels, but it now very much includes the specificity of climate-related policies. What types of renewables should be favoured and what incentives should be adopted to promote them? How can consumption of energy be reduced and what incentives are best for promoting this? What are the best low-carbon transport options for a particular country? How can an energy transition secure jobs and decent livelihoods? And, possibly the biggest question: What should be the pace and scope of transition?f2c965992ada The answers to these questions determine how hundreds of billions of dollars will be spent.

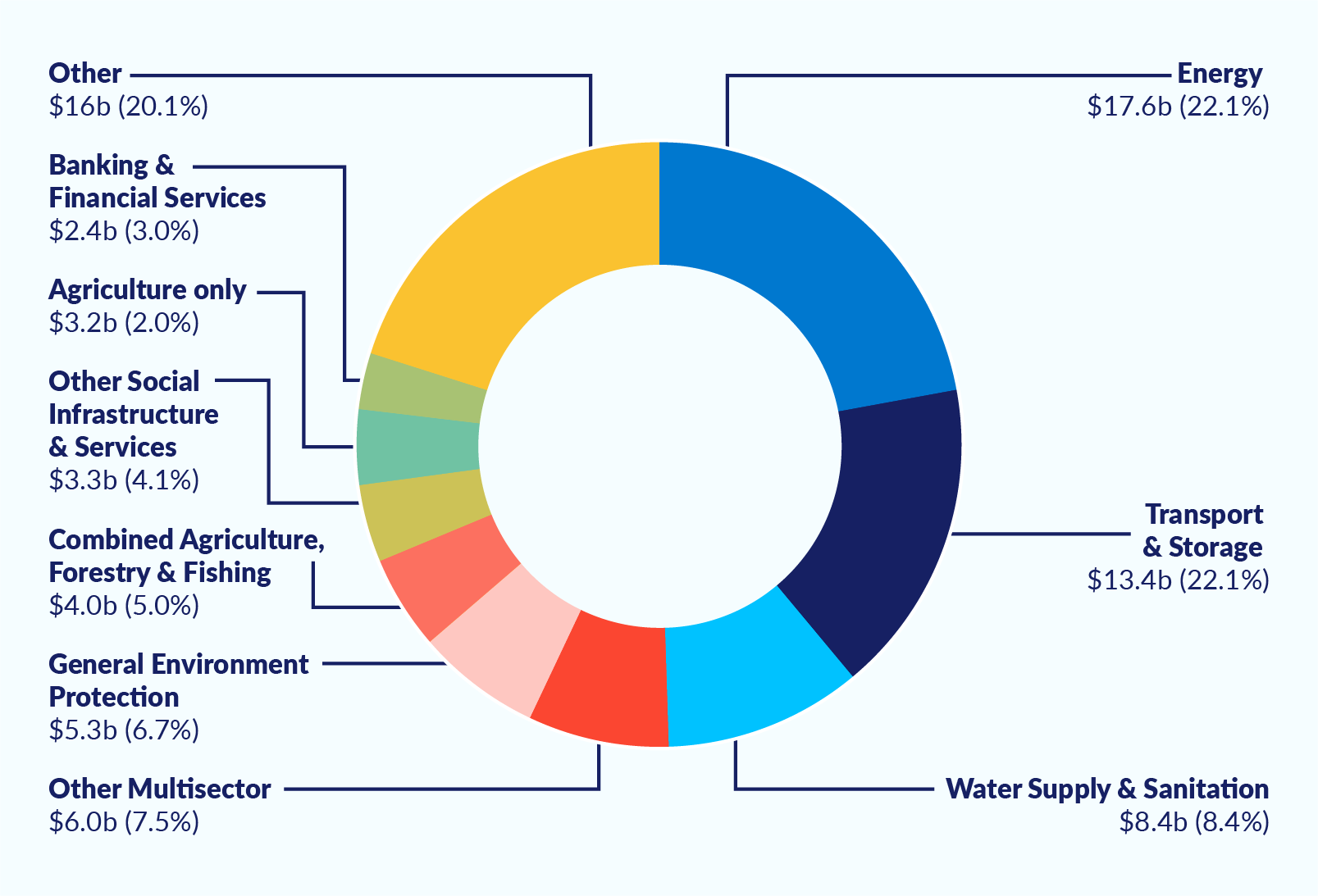

The OECD categorises CRDF into 41 sectors. Figure 1 shows the top ten sectors in terms of their percentage share of total CRDF, with the dollar value shown in the pie chart.

Figure 1: Climate-related development finance: Top ten sectors, 2019 (US$ billion)

Source: OECD, 2019.

As might be expected given their importance to mitigation and adaptation, Energy, Transport and Water Supply and Sanitation are the largest sectors and receive just under half of all CRDF: 47.3% or US$39.4 billion. What is more surprising is the relative insignificance of agriculture, forestry and fishing, whether as a combined sector or as single sectors, given the impact climate change will presumably have on them. The combined value of CRDF directed to these three sectors across all the categories (dedicated and combined) in which they are represented, is just under 10%. The greatest surprise is CRDF for construction, which is recorded in both ‘Construction’ and the combined category of ‘Industry, Mining, Construction.’ Construction is essential to climate adaptation initiatives, but its share of CRDF was a mere 0.41% (US$328 million) – too insignificant to show in Figure 1.

The energy sector is particularly relevant to analysis of lobbying and corruption around climate action because of its share of CRDF, its importance for emissions and for other sectors (eg, low-carbon transport), the influence of energy corporations on policy,43259a6b3dfd and the number of corruption scandals involving energy firms.796ccaddbca7 For these reasons, the energy sector also attracts more attention regarding unequal lobbying compared to other sectors.

It is no surprise that as the window for keeping global warming to less than 1.5° Celsius rapidly closes,eaa591c88876 and therefore definitive policy options for climate action become more urgent, lobbying has intensified.f55e1aae02b6 Climate change is the policy challenge of the century and has also created equally important lobbying opportunities. Given the sums involved, there are significant profits to be obtained by corporations that manage to persuade governments to adopt policies favourable to their business – and this is an era of exceptional policy change. There is also an opportunity to influence policy directions for decades to come as governments embed long-term solutions to reducing emissions, finding alternative energy sources, and adapting to current impacts. Finally, climate policy is competitive and complex, as stakeholders compete to influence policymakers. Different policy directions will cause different environmental, social and economic consequences, drawing in many additional stakeholders. Furthermore, because of complexity, lobbying entities such as corporations, industry groups, think tanks, CSOs, and governments themselves (in the case of multilateral discussions), often hire their own suite of technical experts. These experts may recommend different energy alternatives, models for transition, or incentives to reduce GHGs.

Climate-related donor finance

Given the financial, ecological and human development stakes of slowing global warming, lobbying pressure on policymakers is likely to increase, including in the international development sector. Any donor or recipient government is a potential target for lobbying, but donors and recipients with large climate-related programmes are likely to attract more attention.

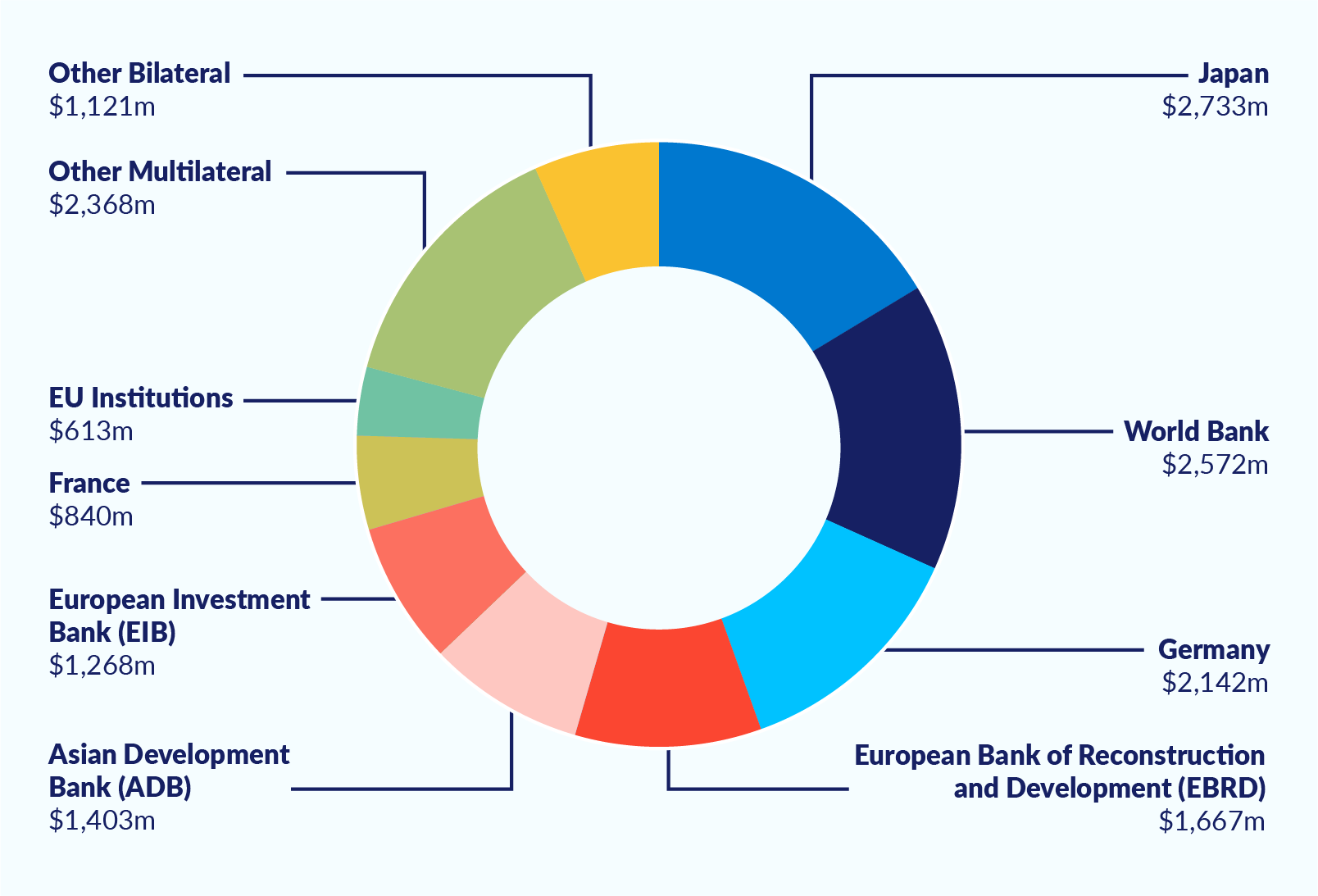

Figure 2 shows the top ten donors of CRDF to the energy sector in 2019 – in total there were 46 bilateral and multilateral contributors. It shows that 79% of energy-related CRDF came from multilateral sources, and 21% came from bilateral sources (including EU institutions). Six contributors – Japan, World Bank, Germany, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Asian Development Bank, and European Investment Bank – contributed 70% (US$11.8 billion) of the total of US$17.6 billion.

Figure 2: Top sources of energy sector climate-related development finance, 2019 (US$ million)*

* Smaller multilateral donors are bundled into ‘other multilateral.’ Smaller bilateral donors are bundled into ‘other bilateral’.

Source: OECD, 2019.

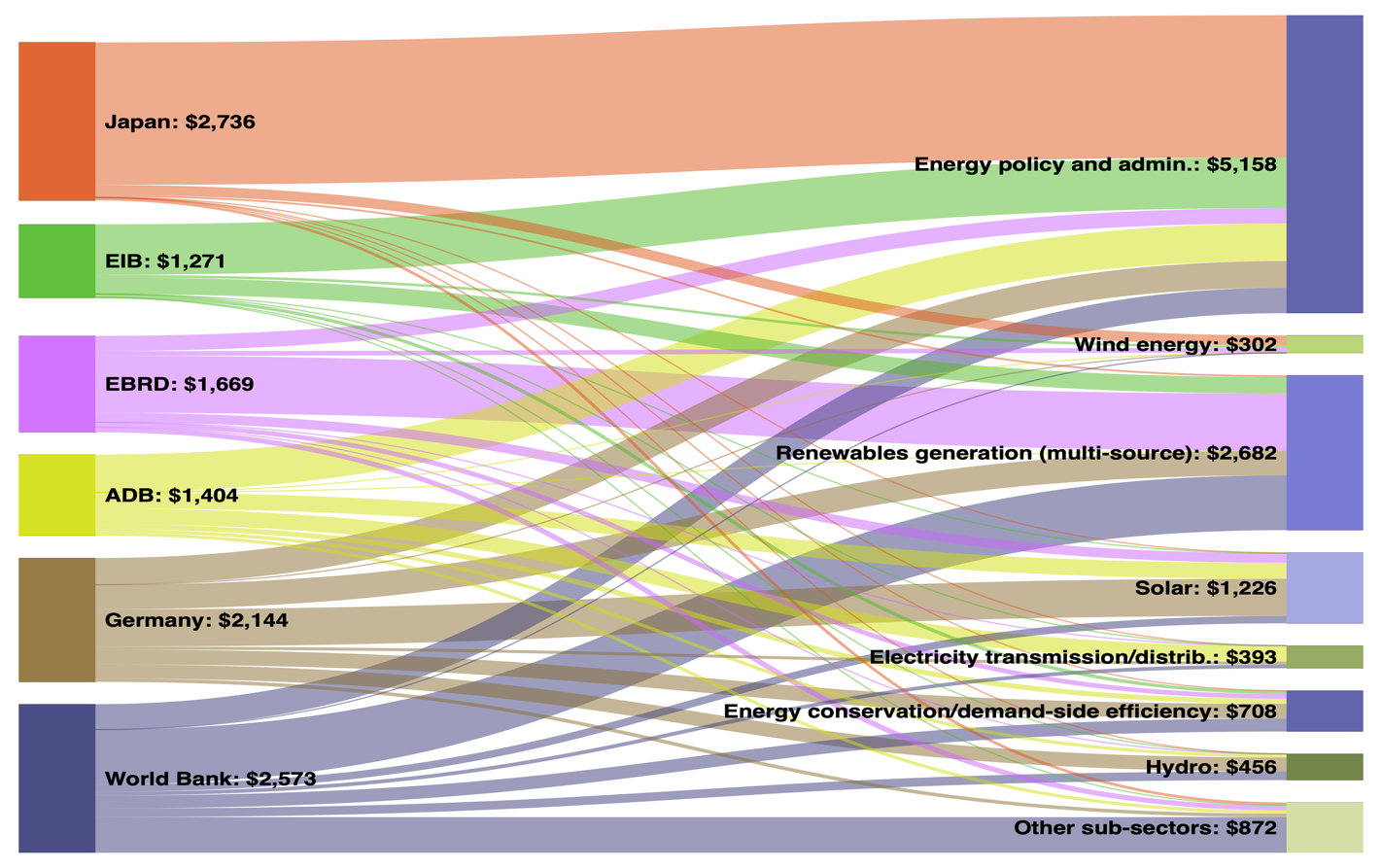

Figure 3 shows the distribution across different energy subsectors of the six top donors’ CRDF. It reveals where donors concentrate their investments and, therefore, where stakeholders interested in shaping policy are likely to target their lobbying efforts.

Figure 3: Top six donors of climate-related development finance energy sub-sectors, 2019 (US$ million)

Figure 3 shows that much CRDF goes to renewable energy initiatives that involve new infrastructure, such as hydro, wind, solar and multisource renewables facilities (for example, combining wind and solar), as well as electricity transmission and distribution networks. The emphasis on these subsectors means that a lot of these funds are probably used for procurement and construction, both notorious for corruption risks. Construction usually requires purchase or use of land, raising issues around free, prior and informed consent by land users and landowners, as well as compensation and creation of alternative livelihoods – elements of a just transition. These factors, plus the value of infrastructure contracts, create incentives for stakeholders to lobby donors and recipient governments over policy, planning, implementation and overall project goals.

Even more pertinent, given that climate policy development is in a state of flux, is the fact that 44% of these six donors’ CRDF targets energy policy and administration (the top-right category in Figure 3).5b33e62cdca1 Funding for this subsector comprises 30% of all energy sector CRDF, or US$5.2 billion. It is on the issue of policy that some energy corporations have concentrated their lobbying, often with far-reaching implications – see Box 3.

Box 3: Shell directly crafts text in the Paris Agreement

At a side event at the 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP24) in Poland, Shell’s chief climate change adviser, David Hone, explained to delegates the role of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA). IETA is a business lobby of fossil fuel producers that seeks to influence governments and multilateral organisations to adopt ‘market-based climate solutions’ in response to climate change. Hone boasted, ‘We have had a process running for four years for the need of carbon unit trading to be part of the Paris Agreement. We [IETA] can take some credit for the fact that Article 6 [of the Paris Agreement] is even there at all. We put together a straw proposal. Many of the elements of that straw proposal appear in the Paris Agreement. We put together another straw proposal for the rulebook, and we saw some of that appear in the text’.

The precise words contributed by IETA to Article 6 remain unknown. However, Clause (b) states that the new mechanism to be established will aim ‘To incentivize and facilitate participation in the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions by public and private entities authorized by a Party’ [emphasis added]. This wording allows private parties to demand incentives (presumably financial) and participation in mitigating greenhouse gases, effectively legitimising lobbying over the mechanism. (It does not differentiate between private parties, which could include civil society organisations, energy firms, and others.)

In addition to corruption risks around lobbying being related to specific sectors and subsectors, they are also related to jurisdiction. Some places are more corrupt than others. Table 1 lists the top ten recipients of energy sector CRDF in 2019, which received a combined 53% of all such finance (US$8.8 billion of US$17.6 billion). Their ranking on Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index (CPI) is shown, alongside a ‘freedom assessment’ of political rights and civil liberties that is relevant to the ability and capacity of stakeholders to engage in policymaking, as discussed below in the section ‘Contexts where inclusive processes face challenges.’

|

Total |

8,832 |

||

|

Top ten recipients |

US$ million (2019) |

CPI rank (2020) |

Freedom assessment (2020) |

|

1. Bangladesh |

1,821 |

146 |

Partly free |

|

2. India |

1,649 |

86 |

Partly free |

|

3. Uzbekistan |

1,593 |

146 |

Not free |

|

4. China |

999 |

78 |

Not free |

|

5. Colombia |

591 |

92 |

Partly free |

|

6. Brazil |

564 |

94 |

Free |

|

7. Turkey |

459 |

86 |

Not free |

|

8. Ukraine |

416 |

117 |

Partly free |

|

9. Egypt |

401 |

117 |

Not free |

|

10. Morocco |

339 |

86 |

Partly free |

Sources: OECD, 2019; Transparency International, 2020; Freedom House, 2020.

Of the ten countries in Table 1, China is perceived to be the least corrupt (ranked at 78). Four countries – Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, Ukraine and Egypt – have a very poor ranking of more than 100. These rankings suggest that systemic governance risks exist around any Official Development Assistance (ODA) channelled to these countries.

Policy selection by a CRDF recipient, or by any country, can help or hinder energy corporations’ profit-making – as will corresponding compliance regimes introduced to regulate the initial policy choice. In countries where national energy policy is heavily influenced by a donor, such as by a multilateral development bank as part of an international development programme, corporations have every incentive to lobby both the donor and recipient to obtain advantageous policy outcomes.

There is evidence that pressure to promote non-renewable energy from coal has had an impact on policy selection in China, India, Indonesia, Japan and Bangladesh, although any connection to an international development programme is unknown. Four of these countries (China, India, Indonesia and Bangladesh) are significant recipients of ODA generally, and three (China, India and Bangladesh) are in the top ten of energy sector CRDF recipients. All five countries have regulated and semi-regulated energy market structures determined by policies that benefit legacy coal operators.895a8493767a Coal plants in all five countries produce energy more expensive than renewable alternatives and are ‘…being propped-up by subsidies and policy-driven support’.f5790e5ec7bf Together, these coal-fired power stations, which are protected against competition and would be unlikely to survive in a market offering energy alternatives, represent 27% of global coal plant energy output. Such protection and investment also goes against a worldwide trend: despite proposals for coal-fired power plants collapsing 76% since the Paris Agreement in 2015,1af37487b59c these five countries are home to 80% of planned new global investment in coal.

Selection of an energy policy has a cascading effect throughout the global economy. For example, low-carbon transport requires renewable energy, both of which require certain minerals. This need creates incentives for mineral producers to lobby for renewable energy policies in countries where these minerals will be consumed (for example, in the form of wind farms or electric vehicles). It also creates incentives to lobby for policies favourable to mining in countries where the minerals are found (even though the final products may be not be used in these locations).

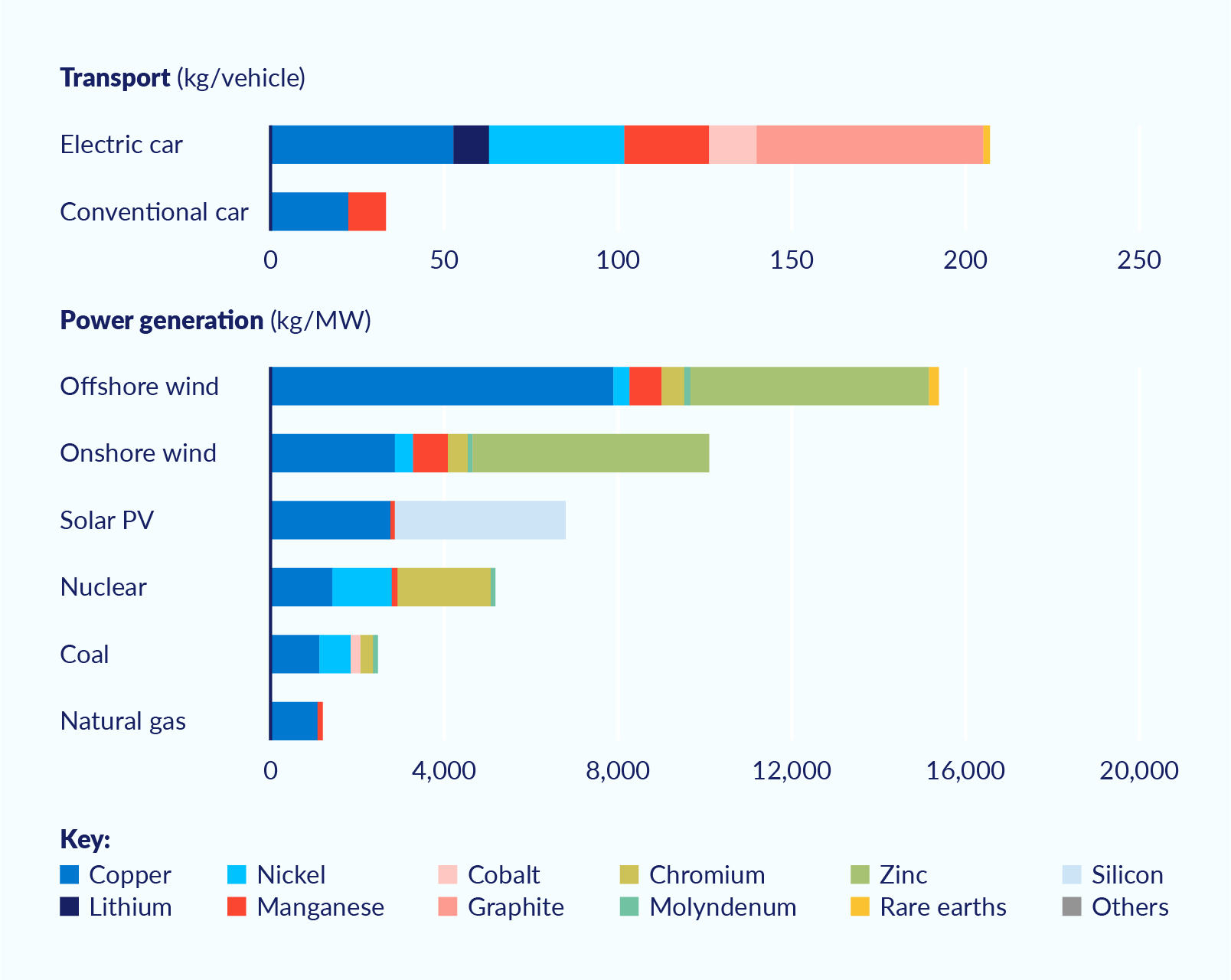

The International Energy Agency analysed the requirements for certain minerals by low-carbon transport and power generation compared to the conventional car industry and fossil fuel industry. Figure 4 shows that producers of copper, nickel, graphite, zinc and silicon stand to gain from an energy transition that favours wind and solar, because these energy sources require those minerals. Conversely, it also shows that producers of coal and natural gas (as well as copper) will gain from continued fossil fuel production.

Figure 4: Minerals used in selected clean energy technologies

Source: International Energy Agency, 2021: 6.

Global mining companies will inevitably try to lobby governments for energy policies favouring an expansion in mining necessary for low-carbon energy and transport. (They will also lobby for policies favourable to mining generally.) Similarly, global fossil fuel companies will lobby governments for policies that soften the consequences of a transition to renewables. Companies whose activities cross both renewables and non-renewables (such as Brazil’s Vale or Switzerland’s Glencore) will also lobby, but they may push for policies that benefit both areas of profit-making. Having assessed the perceived risks to their assets and to shareholders, other corporations have publicly embraced the urgency of climate change, accepted the science, and abandoned fossil fuels.fc365deb2772 For example, Rio Tinto sold its last coal assets in 2018, although it will no doubt continue to lobby for policies favouring its remaining interests.

International development programmes focused on climate mitigation or adaptation activities occur within this global context of high-stakes competition, manoeuvring and lobbying. There are two lessons from this situation. First, (as noted above) international development focused on climate action is unlikely to be isolated from broader lobbying; donors and development practitioners should be prepared. Second, given the power and influence of multinational resource corporations, CSOs and community organisations – which are stalwarts of many international development programmes – may struggle to be included or heard equally in climate debates.

In their research on Tanzania, Fjeldstad and Johnsøn72edd73c96de show that CSOs and local business can successfully shape resource policy by lobbying. However, (as is discussed below in the section ‘Contexts where inclusive processes face challenges’) whether local stakeholders can influence policy will depend on the specific political context.

Lobbying in international development

Lobbying of donors, recipients and international organisations is an established feature of international development. It is undertaken by a wide variety of organisations and groups, as well as project management firms, all seeking to influence the direction of policy and thus selection and expenditure on programmes. For example:

- In the USA, 164 lobbyists had 84 meetings with USAID officials in 2020, an average of one meeting every three business days.7b39a3cddb40

- The Australian Council for International Development is a peak body for NGOs that seeks to be an ‘influential policy voice’ in the international development and humanitarian aid sector.d27c2b299640

- In the Netherlands, the government awarded €1.9 billion to 20 alliances of NGOs between 2011 and 2015, to enable them to engage internationally in ‘lobbying and advocacy’ on sustainable livelihoods and economic justice, sexual and reproductive health and rights, and protection, human security and conflict prevention.e817ad50f0b3

- An example of lobbying that profoundly shaped donor policy is the 1973 Helms Amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act. CSOs, especially Christian organisations, successfully lobbied US Congress to adopt this amendment, which prohibits USAID from funding any organisation that supports or performs abortion.496eb2b80091

Lobbying techniques essentially involve two things: (a) lobbyists communicating ideas in the hope that the ideas will influence the decisions of the lobbied party; and (b) creation of an experience or the giving something designed to make the lobbied think positively about the lobbyist – this technique is designed to create a sense of reciprocity or obligation that will cause the lobbied party to make decisions favourable to the lobbyist. Lobbying laws seek to regulate both types of techniques, but especially (b) which, if unregulated, can involve egregious gifts, bribes and kickbacks.

If regulations are in place, registering and publicising direct lobbying by a business or interest group is straightforward. Such regulations generated the data about exclusion in the Australian and US lobbying examples in Box 2. Critics of lobbying have a particular concern about indirect lobbying that obscures the lobbying party and contributes to misinformation and political polarisation around climate action.73e88b079e80 Indirect lobbying techniques are used in traditional media and social media: to encourage members of an interest group to communicate directly with policymakers to pressure them to endorse an opinion; to expand outreach through social media, including in some cases the use of so-called ‘fake news’ to encourage action; and to stage media events, issue media releases and mount advertising campaigns.8a1a9d091dd9

Table 2 lists parties that commonly engage in lobbying and the parties that are commonly lobbied (those decision makers who lobbyists want to influence). It divides the list into the general government context, then adds nuances relevant to international development.

Table 2: Lobbyists and the lobbied

|

Lobbying parties |

The lobbied |

|

In the general government context |

|

|

|

|

In the international development context |

|

|

|

Sources: Bekoe and Kuyole (2016), Fjeldstad and Johnsøn (2017), ICAC (2021), and Van Wessel et al (2015).

Table 3 lists common lobbying techniques under the categories of the potential ‘communications’ and ‘experiences/gifts’ that may be used in either direct or indirect lobbying, as well as regulatory responses to these techniques. Whether these techniques are permitted, recorded or regulated will vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Table 3: Common lobbying techniques and regulatory responses

|

Potential communications between lobbyists and lobbied |

Potential experiences/gifts offered to the lobbied |

Regulatory responses to lobbying techniques |

|

|

|

Source: Based on ICAC 2021 with some additions by the authors

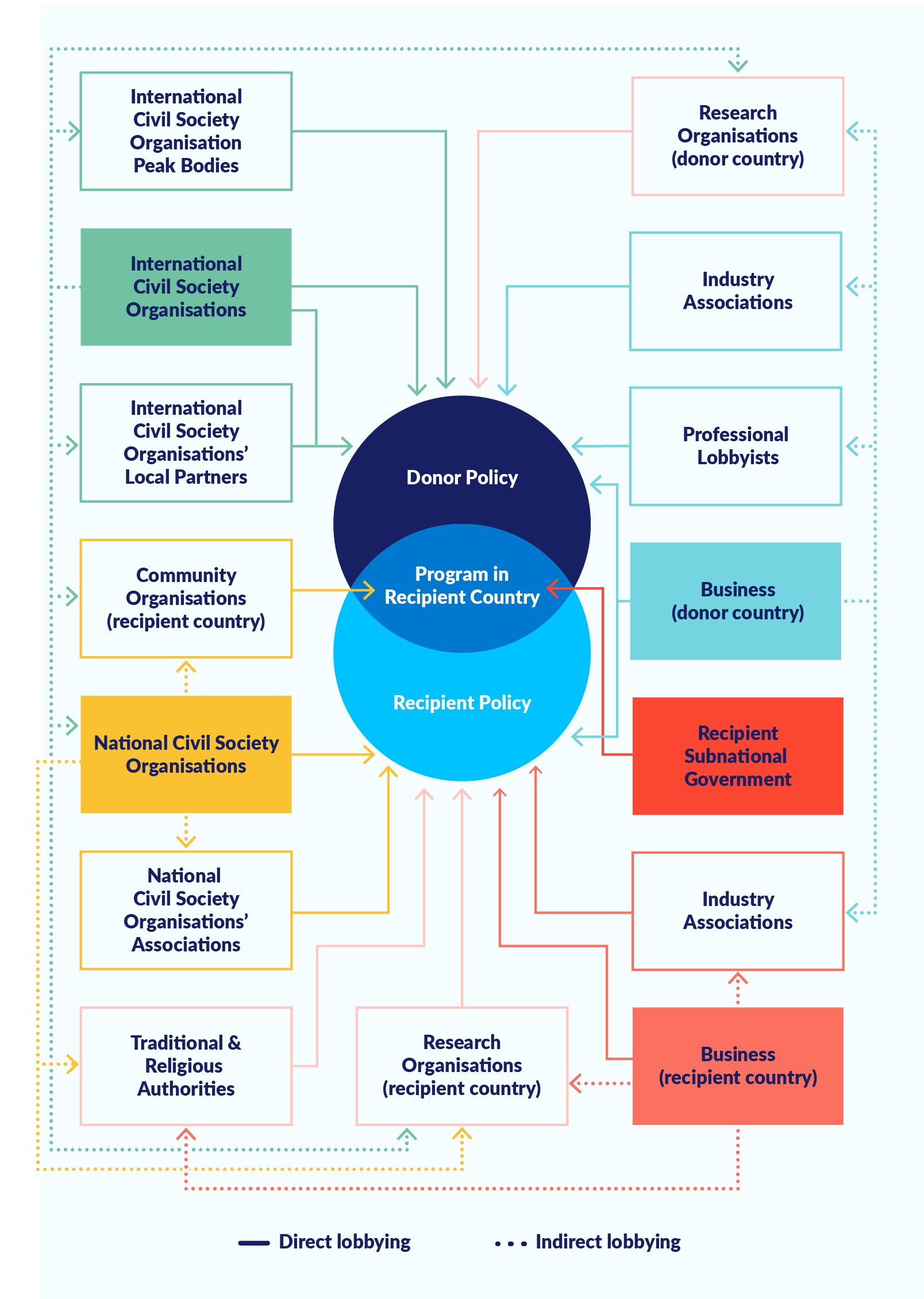

To better understand the possible interaction between the parties in Table 2, Figure 5 is a stylised representation of interaction in a hypothetical development scenario where stakeholders seek to influence programme policy through both direct and indirect lobbying.

Figure 5: Hypothetical lobbying scenario

Figure 5 depicts four major types of lobbying parties: business in donor countries, business in recipient countries, international CSOs, and national CSOs in recipient countries. It also includes recipient subnational government (such as provincial government) which may actively campaign to host project activities. The lines representing direct and indirect lobbying in some cases lead to the same parties. This is because parties such as research organisations in donor countries, or traditional or religious authorities in recipient countries, may be funded by multiple sources to influence policymakers.

The Venn diagram at the centre reveals a notable difference between lobbying domestically and lobbying in the international development context. Unlike domestic lobbying where elected lawmakers are the likely primary target of lobbyists, in international development there are effectively three target areas: the donor’s policymakers; the recipient government’s policymakers; and the managers of the programmes themselves. Although aid programmes are usually aligned with both donor and recipient policies, programme managers may have discretion to allocate funding to activities, and this discretion can make programme staff a target for lobbyists. The Venn diagram depicts this relationship.

Another difference between lobbying domestically and lobbying in the international development context, is that not all parties lobbying in donor countries are active in the development context. For example, stakeholders such as labour unions, which can be very powerful in domestic policy debates over climate change in donor countries,296328c6fe60 appear largely absent from the development context. Unions sometimes fund international projects – for example, for workers or counterpart unions in developing countries. However, it is hard to imagine labour unions from donor countries lobbying over climate policy in a recipient country (although domestic labour unions in the latter may well do this).

Tools for donors to manage lobbying

Fortunately for donors, there are approaches beyond bureaucratic methods to address concerns around exclusionary lobbying. There are also numerous tools already available for this purpose.

‘Good’ international development is alert to exclusion and demonstrates best practice at inclusion. Development practitioners know the importance of connecting with stakeholders at all levels (community development is an entire subfield of development and donors routinely work with CSOs and community organisations). Practitioners, especially national staff, also know and can map local stakeholders. Furthermore, many policies and programmes have a specific focus on marginalised groups, including women, poor people, displaced people, the LGBTQ+ community, ethnic minorities, religious minorities and people with disabilities. Good development practitioners also understand and routinely use techniques for obtaining stakeholder input into programme and activity design – for example, through community meetings, workshops, conferences, steering committees, focus groups and social media. Good practitioners understand that an open inclusive process is a development goal in itself.

Many donor agencies and other organisations that implement international development programmes have had policies and administrative tools in place for years to promote inclusion. As these mechanisms vary across donor programmes, it is useful to look to agreed global standards around inclusion and development as a guide to what non-exclusionary lobbying should look like. To do so, this paper focuses on the UN’s SDGs:

- SDG 16 is to ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’. [emphasis added]

- SDG 17 is to ‘Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development’. [emphasis added]

‘Inclusive’, ‘justice for all’, and ‘partnership’ capture the thrust of Warren’s reconceptualisation of corruption to emphasise the ills of exclusionary practices in the political context. SDGs 16 and 17 also simplify the development practitioner’s tasks regarding lobbying and climate change initiatives: they need to adopt tried, tested and accepted principles of development and use them as the basis for broad inclusive engagement on climate action.

Established standards and legal and administrative tools used in procurement for development programmes can also be used to minimise inequality of access and exclusion in lobbying. Public sector procurement is highly regulated with guidance available on principles, standards and anti-corruption tools. These are all designed to ensure that engagement is transparent, accountable and occurs in an equal manner, so no supplier is given an unfair advantage. In terms of managing corruption risks in supplier engagement, procurement creates similar challenges to lobbying.

Governments, including their donor and anti-corruption agencies, are highly familiar with anti-corruption tools for procurement and have produced abundant rules and guidance, as have the OECD, multilateral banks, and CSOs (including Transparency International). The UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) refers to procurement, and U4 itself has published resources on procurement.2d2c55fedc74

Not all aspects of procurement are relevant to lobbying. Article 9 of the UNCAC states that procurement systems should be based on ‘transparency, competition and objective criteria’,cd98001b18d3 and are important for buying goods and services. However, it is the transparency and objective criteria principles that are relevant to managing corruption risks in lobbying. Promoting ‘competition’ among lobbying parties could result in stakeholders with the most resources gaining privileged access.

The following measures around procurement transparency could be directly adapted to preventing exclusion in lobbying around climate action:

- Create easy access for all stakeholders to information about (a) the policymaking process and (b) existing information about an issue being considered by the donor or recipient.

- Register communications and engagements and ban secret meetings between policymakers and other stakeholders.

- Communicate equally with all stakeholders – for example, all parties receive all communications about an issue, and all parties’ policy positions are available to all lobbying parties.

- Create a standard formal response to requests for meetings, stating that meetings can be held only if all programme stakeholders are invited, or the meeting must be publicly disclosed (even if not all the content is).

- Where private meetings are advisable, consider what details should be released publicly for transparency purposes.

- Make information available to the public about the ‘who, what, where’ of communications and engagement – for example, post online meeting diaries and any written submissions that may have been made (similar to what occurs with public commissions of inquiry).

- If communications and engagement result in a specific contract award, such as for a significant resources project, this contract could be posted online, in keeping with transparency standards (see for example, the EITI).

- Create integrity pacts between stakeholders and policymakers about standards of conduct, disclosure of conflicts of interest, non-exchange of gifts or experiences, and commitments to avoid breaching lobbying rules.

- Adopt a system for managing conflicts of interest, investigating and sanctioning rule breaches, and publish them online.

- Create and enforce penalties if rules are breached, such as bans on further engagement on an issue, as well as punishments for officials who tolerate, or engage in, exclusionary practices.

Regarding ‘objective criteria’, donors and recipients could usefully identify in advance the broad type of information and opinion required to make a policy decision. Stakeholders capable of providing information in response to these criteria could then be invited to participate.

- Publish online the criteria used to grant opportunities to lobby.

To promote inclusivity and avoid exclusion in climate action, there are practical steps donors and recipients can take:

- Map the stakeholders interested in climate policy and identify any who appear missing from forums.

- Identify why stakeholders may be missing (lack of resources; unaware of process; warned not to participate; lack of communications in local languages; systemic discrimination) and remedy the situation.

- Make participation in policy forums easy, including: subsidies for travel, meals and accommodation for some stakeholders; hold multiple opportunities to have input, including outside major cities; allow submissions in local languages and provide translators and interpreters; use accessible venues; have staff available who can explain the submissions process to uncertain participants.

- When submissions can be made in person or via video conference, consider making these sessions public so anyone can attend and listen to what is said, or livestream and record the session and make it available online.

- Actively communicate the principles driving the engagement process to stakeholders before meetings or public hearings. Tell them that exclusionary practices will not be tolerated and that stakeholders risk sanctions or their submissions being disregarded if they seek engagement outside agreed forums.

Donors and recipients should educate development programme staff – especially staff at high risk such as executives, managers, and programme design consultants – to be prepared. In particular, that:

- lobbying is designed to influence how the lobbied parties think about an issue

- attempts to lobby can occur in a variety of settings, from a formal attempt at a head office, to an unexpected visit to a programme office in a developing country, or at a bar or conference

- ostensibly ‘friendly’ approaches by stakeholders may, in fact, be part a pre-planned, well-resourced, strategy. Just as suppliers offer gifts and experiences to procurement staff to make them feel positive about the giver, offers of gifts or experiences by stakeholders with an interest in climate policy are driven by the same motivation.

Donors (and recipients) working on climate initiatives where there is engagement with corporate stakeholders, could also educate these stakeholders about international development. This could be as simple as a half-day workshop on how development works, explaining the SDGs, and the fundamental importance of inclusive processes when designing policy and programmes. CSOs and community organisations with a stake in the climate initiative being considered could be asked to present to the corporate stakeholders. If the business has already joined the UN Global Compactd695d0293a9f less work will be required, but company field staff may not know much about head office commitment to such initiatives.

Businesses, CSOs and other parties interested in avoiding exclusionary practices can adopt many of these points. For example, they can: sign integrity pacts focused on lobbying practices; avoid engagement with policymakers outside channels established for the issue at hand; and accept transparency around their participation and submissions (such as making submissions publicly available). Ron and Singer4a1ba9aafe25 argue that businesses should adopt an ethical framework, such as a corporate code of ethics. While including obvious avoidance of ‘suitcases full of cash’ in common with standard anti-corruption approaches, such codes could also emphasise actions that do not block or overwhelm participation by others.

Contexts where inclusive processes face challenges

Much of this advice will be difficult to implement under regimes that constrict political rights and civil liberties. Deliberative policy processes that allow or facilitate inclusion by a variety of stakeholders only work where civic space exists and is protected, because people need to feel free and safe expressing views on government policy – and be legally able to do so without the threat of being charged with subverting the state. Such contexts usually exist in democracies and not under non-democratic regimes.

Of the ten top recipients of CRDF in Table 1, only Brazil (a democracy) is assessed as fully ‘free’ by Freedom House, five are ‘partly free’ (Bangladesh, India, Colombia, Ukraine, and Morocco), and four are assessed as ‘not free’ (Uzbekistan, China, Turkey, and Egypt).cef3a3df1bbe While donors may still have opportunities in these countries to engage on anti-corruption issues generally,362cc4e94078 advocating for inclusive, open, deliberative processes around climate action is likely to be challenging and face outright opposition from recipient governments. Furthermore, when authoritarian regimes do permit CSOs and community organisations to participate in policy discussions, these stakeholders may have close ties to the ruling party and elites and simply repeat government policy positions. Funding bodies may be faced with the choice of constrained and flawed engagement, or total disengagement.33a6cbc35482

Azerbaijan’s membership of the EITI illustrates how changes in civic space affect stakeholders’ ability to engage in debate over resource policy. In 2003, Azerbaijan was the first country to be designated as compliant with EITI standards. However, from 2013 to 2014 the government introduced legislation that meant civil society was no longer able to engage critically and fully in the country’s EITI process. The EITI Board downgraded Azerbaijan’s status from ‘compliant’ to ‘candidate’ pending further review. Shortly before the EITI Board was due to suspend Azerbaijan (having decided reform was not forthcoming), the government withdrew entirely from the EITI.

In highly corrupt jurisdictions where buying influence in government is endemic, non-corporate stakeholders will face disadvantages. In the top ten list in Table 1, four countries (Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, Ukraine and Egypt) are perceived to be highly corrupt, and the remaining six are all mid-ranked on the corruption perceptions index. Yet, research into the relationship between climate vulnerability and corruption shows that, in corrupt countries, climate action is often most urgent.255652697bb9 For example, Bangladesh is one of the most climate-change vulnerable countries in the world.

Donor programmes funded through blended finance – an increasing trend of combining private sector contributions with ODA to fund development activities – have particular vulnerabilities to lobbying, especially where those programmes are directed towards climate action. Energy is the largest blended finance sector, with 35% of all transactions from 2017 to 2019 being energy related.795297625e00 It is reasonable to expect that contributions from a renewable energy firm would only be directed to sources where that firm has expertise. The risk is that the contributing firm, already having privileged access to the donor, lobbies for policies and spending that favour its own energy products, whether or not this is optimal for the recipient’s energy transition. Both donors and recipients are vulnerable to such pressure.

Depending on the jurisdiction, donor agencies are also likely to face the challenge of working with other branches of their own government. Ideally, anti-corruption measures focused on lobbying will be part of a whole-of-government approach. However, many governments channel ODA and CRDF through multiple institutions, and governments may also use other ministries and agencies to engage in debates over climate policy and climate action – for example, foreign affairs, trade, business promotion, environment or natural resources. Such institutional arrangements will complicate the adoption and implementation of anti-corruption tools for lobbying, including those suggested by this paper, even if donor agencies are able to take the lead.

What good lobbying looks like

To better understand how exclusion in lobbying can be avoided, and how inclusion can be achieved, it is worth considering what ‘good lobbying’ might look like. This section reimagines the Tanzania case researched by Fjeldstad and Johnsøn.c9bd9d9f071d The case focused on policy development around Tanzania’s new offshore natural gas fields – narrower than climate policy or a climate change mitigation or adaptation programme, but featuring a potentially similar set of stakeholders.

Fjeldstad and Johnsøn found that lobbying was unregulated and there was a ‘chaotic policy environment, where no agency or ministry was given the clear leading role’.e6d7e1fbefec Public hearings were not held, something that was protested by the Tanzania Civil Society Coalition. Donors had previously pushed for multistakeholder consultations involving, for example, key ministries, local government, business, universities, CSOs, the media and donors around energy developments. However, this never occurred, even though the Tanzanian government had agreed that such consultations were a good idea. Donors nevertheless supported the development of the natural gas sector, and also tried to influence policy (that is, they were lobbyists themselves). Key donors were Norway, Germany and the International Monetary Fund. Tanzanian energy officials were generally cautious about following donor advice, given previous negative experiences with the World Bank.e57848adf3e9

The only stakeholders invited to provide formal feedback on the draft Act to govern the development of the new resource, were international energy corporations. They were given a four-day deadline. Prior to this offer, international corporations did not lobby actively or publicly at the legislative level but influenced decision makers ‘by stealth’ through their technical contacts with officials in public administration (private sector technical expertise was indispensable to the government).

Despite not being offered a formal opportunity for consultation, national, locally owned, businesses successfully lobbied through back channels for inclusion of local content requirements in energy policy. The local EITI chapter was also a ‘winner’, successfully persuading the government to adopt transparency provisions around revenue. Local citizens and CSOs (other than EITI and local business groups) felt sidelined.

Accepting Fjeldstad and Johnsøn’s observations at face value, it is useful to consider what could have been done differently. The following points are not a process sequence, but simply the components of a different approach. Many sub-steps are omitted that are essential to development planning.

- The Ministry of Energy and Minerals and donors interested in supporting natural gas development could formally agree that lobbying will be permitted and managed. It is important to emphasise managed because this is all that is possible in the absence of a Tanzanian lobbying law that stipulates standards, regulations and penalties.f7bd18ecdd62

- Agree on a multistakeholder group that will set the rules and manage engagement.

- Donor support could be contingent on a consultative transparent process.

- Map stakeholders with a likely interest in energy development, including where they live (important to know for engagement) and any systemic obstacles to participation by, for example, regional communities, poorly resourced organisations, or women and other marginalised groups.

- Identify the optimal medium for communications: radio, social media, television, newspapers, industry bodies, associations of CSOs and community groups.

- Educate government and donor officials that stakeholders are likely to try to lobby them, and have a plan for how they should respond if this occurs.

- In English, Swahili and other languages, invite stakeholders to participate. All communications should include rules around participation.

- Require stakeholders to sign integrity pacts committing to only using agreed channels of communication.

- At a minimum, hold consultations in Dar Es Salaam (the business capital with foreign corporations’ offices), Mtwara (the closest town to offshore gas fields) and Dodoma (the site of parliament).

- Make funds available to support participation by poorly resourced groups.

- Keep records of all meetings and communications, and make them available to the public by posting them online.

- Ensure that formal submissions – through in-person attendance at meetings, livestreaming or making written and oral submissions available online – are ‘discoverable’ to the public, and advertise that this information is available.

Caution is needed when considering measures such as minimising exclusionary practices. Fjeldstad and Johnsøn argue ‘What may seem like corrupt and dysfunctional institutions from a Western perspective are well-functioning vehicles for patronage in the local context’.b89b3d288aee The lack of coordination and policy ‘chaos’ in Tanzania created an environment that some insiders understood and could operate in very well – for example, local business and CSOs (such as Tanzania’s EITI). By contrast, outsiders – foreigners, donors, multinational corporations, international CSOs – probably struggled to identify where power lay, and therefore who and how to influence. From this perspective, the lack of lobbying regulation could be considered a deliberate rational strategy to exclude foreign influence. However, such a situation should not be romanticised: local stakeholders such as national community organisations, CSOs (other than EITI), and citizens were also excluded from the process.

National stakeholders may have been willing to embrace a managed policy development process if they were assured they would have the same access as energy corporations. Energy corporations may have been willing to forego opportunities for private influence, if they were assured they could make submissions to lawmakers within a reasonable timeframe. Involving stakeholders in designing the consultative process itself may also have given them confidence that it would be a fair process.

Conclusion

There are multiple types and layers of risk to inclusive lobbying practices. In addition to risks around common sectors that CRDF is directed at – especially energy and its policy and infrastructure subsectors – there are also systemic risks related to endemic corruption and a constrained civic space, as well as risks related to sourcing finance.

Unfortunately, while lobbying regulations are designed to record and make public what happens between officials and stakeholders, they are not designed to promote inclusion or prevent exclusion. Where anti-corruption or lobbying laws could potentially be used to penalise public officials who allow exclusionary practices, sanctions can be difficult to obtain if those officials did not receive any immediate personal gain. That is, bias was institutional or not deemed sufficiently serious to warrant corruption findings.

Law reform can be slow, and lobbying and anti-corruption regulations are implemented by institutions according to the law. Regulations are unlikely to be sufficient for promoting equal access for all stakeholders in policy development. This is the case for climate action as much as any other sector.

Fortunately, and unlike many other economic and government sectors, development partners have measures at their disposal that can prevent exclusion where legal tools are insufficient. Legal frameworks should be created to regulate aspects of lobbying within bureaucratic control, but it is unrealistic to expect that they will always proactively promote inclusive policymaking. Donors can be guided by existing development principles of inclusion, justice and partnership to avoid exclusionary practices, but also proactively manage engagement with lobbying parties using procurement-style standards around communications, equal treatment and transparency.

Recommendations for donors

Several steps can be taken to level the playing field and ensure equal access to different stakeholders for climate action. In this section we have developed a series of recommendations based on the analysis presented in this report. Key points of our analysis are also repeated here to ensure that the connection between analysis, finding and recommendation is clear.