Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption risks faced by UN agencies and the role of internal audits in countering this.

Caveat

The literature on the role of internal audits within the UN system is limited and, of the few external assessments available, some are dated, such as the Joint Inspection Unit (JIU) reports. While these sources are cited multiple times throughout the Helpdesk Answer, they might not reflect current realities.

This Helpdesk Answer refers to allegations of corruption or misconduct made by third parties but not proven in a court of law. Both Transparency International and U4 do not take a position on the veracity of the allegations discussed here. They are nonetheless referred to as they illustrate some of the types of corruption risks that United Nations’ organisations face.

For some of the cases described in the paper, investigations and institutional responses are ongoing. The author has attempted to establish the status of the case at the time of writing with reference to information available in the public domain. In this regard, it is important to note that reports and outcomes of internal investigations conducted by multilateral organisations are often kept confidential.

Introduction

Corruption in the United Nations (UN) system has been identified as a recurring risk (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016; Beigbeder 2021). Corrupt acts can be perpetrated by such entities’ own personnel or by external third-party partners enlisted to manage funds and implement projects (Jenkins 2016: 1). Uncovered cases and allegations indicate that the range of corruption risks UN entities face is extensive and include acts such as bribery, embezzlement, collusion and favouritism (Bergin 2023). Beigbeder (2021: 192) provides the following list of some of the main risks:

- Use or abuse of privileges by UN staff for their personal gain

- Embezzlement of UN funds or theft of UN property

- Submission of false documents as a basis for undue allowances or grants

- Acceptance of undue excess payments

- Bid rigging

- The search or acceptance of bribes

- Unauthorised outside financial activities

- Other forms of unethical conduct

These all can have severe impacts, leading to the squandering of high volumes of funds and undermining the development outcomes of UN interventions and creating lasting reputational harms (Bergin 2023).

This Helpdesk Answer focuses on the role of internal audits in addressing corruption risks within the UN system. It first explores the different enablers of corruption within UN entities, drawing from two recent case examples as well as the wider literature. Then it outlines the purpose of internal audits as described in international standards as well as the wider literature, outlining the broad three preventive, detective and reactive functions it performs in terms of corruption risks.

Following this, it describes how the UN translates this into practice, describing the various internal audit bodies that have been established, as well as how audit operations typically play out. Lastly, it describes the different weaknesses that have been ascribed to UN internal audits along with good practices and recommendations from experts which signal ways to address these.

Drivers of corruption in UN entities

This section provides a non-exhaustive147e944678ae outline of some of the main drivers of corruption in UN entities. In this section, insights from the wider literature are used, as well as from two recent examples where UN agencies faced allegations of corruption. Basic descriptive overviews of these two cases are first given, and then the drivers are outlined, including by referring to examples from the two cases. Moreover, identified weaknesses of audit functions in these two cases are described in the final section of this Helpdesk Answer. However, it is caveated that these two cases should not be viewed as fully representative given that the incidence of corruption within the UN is influenced by local contexts, delivery modalities and other factors.

These drivers collectively speak to a failure to prevent, detect and react to suspected corruption risks. As will be demonstrated in the following sections, the functions of internal audits are intended to some degree to respond to this, detect and react to corruption. Conversely, weak or ineffective internal audit systems can enable corruption to go undetected and unaddressed, as described in further detail in the final section.

Overview of UNOPS S3i investments case

The United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) is a UN agency that “provides practical solutions in infrastructure, procurement and project management… [to] support peace and security, humanitarian and development projects around the world” (UNOPS n.d.). In 2022, UNOPS became the focus of a major scandal involving its Sustainable Investments in Infrastructure and Innovation (S3i) initiative – a programme intended to mobilise private capital for development projects, such as affordable housing and renewable energy (KPMG 2022a).

Under S3i, UNOPS initiated contracts worth over US$59.7 million to the construction firm SHS Holdings and its affiliated entities as well as a contract to generate business interest in housing development in six other countries (KPMG 2022a). Fraud allegations surfaced and serious conflict-of-interest failures were raised in S3i after media reports revealed SHS Holdings had not fulfilled their contract obligations (see Fahrenthold and Fassihi 2022).

According to a reported into the case written by KPMG, SHS Holdings had no proven track record in delivering large-scale projects and subsequently failed to construct any of the promised housing or secure private investors (KPMG 2022a). Additionally, personnel linked to SHS were connected to another initiative receiving UNOPS funding (KPMG 2022a).

An external advisory review carried out by KPMG found that due diligence and risk management procedures were bypassed, funds were disbursed without adequate safeguards and key investment decisions were concentrated in the hands of a few senior officials (KPMG 2022a). S3i essentially operated as an independent business unit within UNOPS, with limited accountability to governing bodies.

Overview of UNDP’s Funding Facility for Stabilisation (FFS) case

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) is a UN agency that “works in 170 countries and territories to eradicate poverty while protecting the planet”. It helps countries develop strong policies, skills, partnerships and institutions so they can sustain their progress (UNDP n.d.a). In early 2024, the Guardian (Foltyn 2024a; 2024b) reported on allegations of bribery, mismanagement and retaliation against whistleblowers within UNDP’s US$1.5bn Iraq aid scheme, the Funding Facility for Stabilisation (FFS). For example, staff working for UNDP were alleged to have demanded “bribes in return for helping businessmen win contracts on postwar reconstruction projects” (Foltyn 2024a). Interviews with more than two dozen UN staff, contractors and officials described the programme as fuelling the wider culture of corruption in Iraq, with projects inflated, duplicated or overstated in official reporting.

UNDP responded to the allegations by emphasising its “zero tolerance for fraud and corruption” and stated that over the past eight years, its internal oversight agency, the Office of Audit and Investigations (OAI) “has processed more than 130 cases related to the FFS, brought to the attention of OAI by our own staff members and third parties, with prompt action taken by UNDP management in response” (UNDP 2024a). It reported having found that 56 of these were substantiated, and disciplinary action was taken, but that these pertained to third-party vendors (Foltyn 2024b). The same document was circulated to reassure donors, some of whom pressed for an external review to restore credibility, while Iraq’s prime minister ordered the national integrity commission to launch its own investigation (Foltyn 2024b).

In early 2024, the UNDP commissioned an internal investigation into the allegations, while the Iraqi Integrity Commission also launched an investigation but, at the time of writing, no results from these appear to have been made available. However, toward the end of 2024, the OAI conducted a financial and internal controls audit to assess, among other things, reporting, compliance with UNDP procedures, procurement processes and HR management within FFS and found seven out of ten internal controls to be “fully satisfactory” with the remaining three were “satisfactory/some improvement needed” (see UNDP 2024c: 1).

Drivers

Lack of oversight of third parties

Donors may entrust funds with multilateral organisations such as UN entities, but the latter in turn often enlist third parties such as suppliers and implementing partners to spend these funds and deliver programmes. Nicaise (2022) highlights that this often-complex web of relationships has implications for the management of corruption risks as multilateral organisations effectively “discharge responsibility for managing risk to these partners, and on to these partners’ own downstream partners”. If multilateral organisations do not implement maintain sufficient levels of oversight and oblige these third parties to implement safeguards, it can heighten risk exposure.

A 2016 report into fraud authored under the supervision of the Joint Inspection Unitceec7397b149 indicates that when UN agencies entrust implementing partners and third parties with operational functions, it may carry fraudfefd5e0520b3 risks (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016: 22). In the FFS case described above, Foltyn (2024a) notes that governmental personnel were entrusted to oversee construction projects. This in turn, has allegedly resulted in bribery, fraud and extortion, where government officials take a cut of the projects they oversee.

Unclear lines of authority

The complex nature of multilateral organisations means authority is often dispersed across governing boards, executives and field operations, creating accountability and oversight gaps (Bergin 2023; Nicaise 2022). Beigbeder (2021) describes how this is also the case for the bodies responsible for investigating fraud and corruption, and there is a lack of clear procedures and division of labour.

For example, in its external assessment, KPMG (2022a) concluded that an opaque decision-making process meant S3i operated outside of the UNOPS’ framework for administrative and financial rules and procedures. Here, many key oversight mechanisms and segregation of duties were not established, resulting in investment decisions being made without a formal investment policy framework or defined processes. In this environment, management did not take into account the risks involved and, when staff were delegated responsibilities – due to limited information and operational consensus and inadequate due diligence and vetting procedures –high-risk contracts were approved.

Tone at the top

Throughout the JIU fraud report, there is consistent reference to an absence of a strong “tone at the top” in dealing with fraud and corruption and no attempt to promote an encompassing anti-fraud culture in UN agencies (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016: iv–v). Similarly, Beigbeder (2021) found that managers within the UN often demonstrate uneven leadership skills in terms of anti-corruption.

In the S3i case, an external review by KPMG (2022a; b) found that UNOPS had developed a strong top-down approach and systematically reduced the transparent disclosure of information, thereby entrenching a culture in which senior management decisions could not be effectively challenged. KPMG (2022a) interviews found this culture of fear prevented staff from speaking up about wrongdoing due to concerns about career consequences. As a result, the S3i decision-making process was opaque, allowing top management to guide investment decisions and the selection process for partner organisations.

In the FFS case, Foltyn (2024a; b) similarly reported a culture of fear and impunity that, according to staff, extended throughout UNDP’s offices in the Middle East. Staff accused UNDP managers of forming close relationships with government officials and using those connections to avoid accountability and retaliate against employees who raised concerns.

Inadequate whistleblowing and reporting channels

The failure to protect from retaliation naturally leads to the discouragement of whistleblowing, and with that, potential cases of corruption may go undetected (Maslen 2021). Alongside the JIU fraud report, JIU have produced a system-wide evaluation of whistleblowing functions in UN agencies (see Cronin and Afifi 2018).425fe7fbc2395 Both reports found that whistleblower frameworks were poorly designed, protections against retaliation were rarely systemically implemented and no UN agencies had implemented good practice standards (see Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016: viii). A 2019 review found that for many UN organisations, there were still were no designated channels in place for reporting about and investigating allegations of misconduct against leadership officials, such as executive heads and heads of oversight services (Afifi 2019: 26).

For the S3i case, KPMG (2022a) highlighted that the existence of multiple whistleblowing channels created confusion for staff, and it was often unclear to staff how to properly report misconduct through the appropriate mechanisms. These issues were compounded by a fear of retaliation and created widespread mistrust in the whistleblowing function for UNOPS.

Lack of follow-up to corruption red flags

The JIU fraud report notes delays in investigations, and the lack of systematic follow-ups to investigations weakens UN agencies’ capacity to deter and proactively address corruption allegations and incidents, promoting a “sense of impunity among fraud perpetrators in the [UN] system” (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016: ix). This can mean early warnings or red flags go unheeded (Bergin 2023) or even a lack of prompt disciplinary action against culpable staff members (Beigbeder 2021).

KPMG (2022a) found UNOPS’ internal audit agency, the Internal Audit and Investigation Group (IAIG), opened investigations into the accused companies, but took approximately two and a half years to complete its investigations.de05a61e4782 In the FFS case, when allegations of bribery were first reported to the OAI (before the Guardian publication), they initially claimed there was insufficient evidence for an investigation to proceed (Foltyn 2024a). In response, a UNDP staff member described the OAI as “completely dysfunctional” (Foltyn 2024a).

Different factors might feed into a lack of follow-up, such as withholding or ignorance of relevant information. Nicaise and Fanchini (2025: 3)describe the persistence of what they term “strategic ignorance” within multilateral organisations or a “deliberate or systemic condition where information is selectively concealed, downplayed, or dismissed in ways that obstruct accountability and enable misconduct”. They describe how certain organisational rules and norms such as confidentiality protocols, internal discretion and organisational incentives can foster strategic ignorance.

The relationship between internal audit and corruption

Objective of internal audit

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA 2017) describes internal auditing as:

‘[A]n independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organization's operations. It helps an organization accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes.’e967c4cdbbff

Accordingly, an internal audit helps organisations safeguard assets, ensure proper use of financial and non-financial resources, and provide assurance to management that risks are being effectively identified and mitigated (Abdulhussein et al. 2023). In their JIU report, Sukari and Terzi (2016) similarly explain the traditional objective of internal audit within the UN is “to assist executive heads in fulfilling their management responsibilities by conducting a risk-based programme of internal audits to provide assurance that governance, risk and control processes are operating effectively and efficiently, and to offer advice for improvement”.

Internal audit, then, can support the management of integrity risks, which include but are not limited to, fraud and corruption (OECD 2025). The importance of internal audits as an anti-corruption measure has been endorsed by the G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group (2022: 1) which committed to a principle to “strengthen the role and capacity of SAIs [supreme audit institutions] and public sector internal auditors to identify, prevent and counter corruption in accordance with their mandates”.

The OECD (2025) explains that internal audit is one of the key components of a strong internal control system, along with a “risk management framework to help organisations identify and respond to corruption risks”. While it is managers who are typically responsible for carrying out corruption risk assessments of internal operations, internal auditors can support the process in several respects, for example audit reports can be used as a source of information on risks and mitigation measures (United Nations Global Compact 2013).

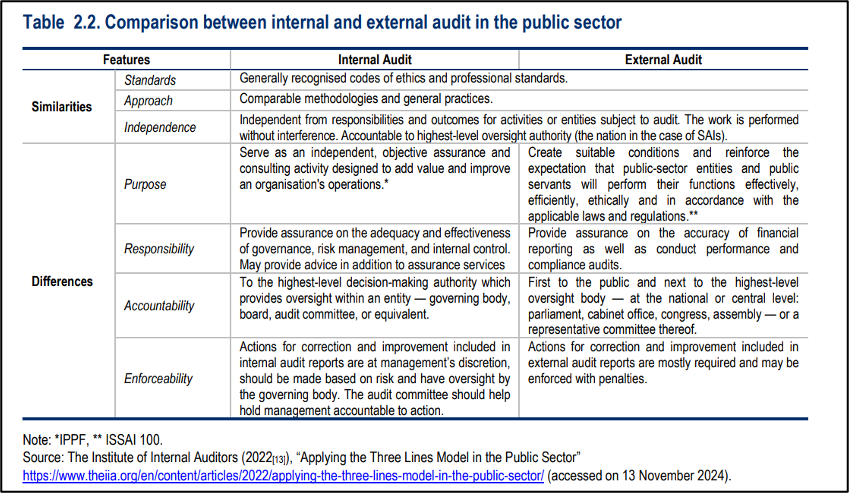

Internal and external audits are distinguished according to several factors, such as whether the auditor is employed by the organisation, or an external contractor is hired (ECIIIA 2019). The OECD provides an overview of some of the key similarities and differences between them, including that both must be “independent from responsibilities and outcomes for activities or entities subject to audit” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: OECD’s overview of similarities and differences between internal and external audit in the public sector

Source: OECD 2024

There are also important distinctions between the internal and external audit functions within the UN system. For example, within the UN system, internal auditors normally report to high-level managers of UN agencies, external auditors typically report to other governing bodies (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 62), and they design and execute their audit plans independently and separately from any internal audit (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 29). In addition, their primary role is to audit the financial statements of organisations, though compliance and performance audits may also occur (Sukayri and Terzi 2016).

The effectiveness of audits as an anti-corruption measure

Several voices in the literature theorise that internal audits can reduce the likelihood of corruption in different ways. This includes: deterring misconduct through the perceived likelihood of detection (Olken 2005); shaping organisational culture by embedding better management practices and risk awareness (Jeppesen 2019); and acting as a visible signal of accountability and sound governance (Tawfik et al. 2023). An internal audit can also directly detect irregularities or misconduct within an organisation before or after the fact (Coram et al. 2006), therefore positioning it in a preventive, detective and reactive role. The wider literature underscores that the effectiveness of an internal audit depends on several of the right conditions being in place, including, but not limited to, sufficient levels of resources, independence, professional competence and sound governance (Abdulhussein et al. 2023; Alqudah et al. 2023; Bari et al. 2024).

However, there have been very few studies which have aimed to empirically the extent to which internal audits are an effective anti-corruption tool.

In its 2024 report, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) analysed 1,921 cases of occupational fraud occurring across 138 countries in government, public companies, private companies and the non-profit sector; 48 per cent of the cases were identified as constituting corruption (ACFE 2024). The ACFE (2024) found that 14 per cent of cases were initially detected through internal audit, compared to 43 per cent from whistleblowing tips and 13 percent from management review, among other channels.

Gustavson and Sundström (2018) measured supreme audit institutions at the national level in terms of their independence, professionalism and transparency, finding those with high scores had a positive correlation with the country’s score on the Corruption Perceptions Index measuring estimated levels of public sector corruption. Avis et al. (2018)analysed Brazil’s anti-corruption program which randomly audits municipalities for their use of federal funds and found that being audited resulted in an estimated 8 per cent reduction in future corruption.

Conversely, an absence of the related enabling factors may blunt an internal audit’s capacity to function effectively (see Alqudah et al. 2023). While it is important to note that an internal audit alone cannot curb corruption (Jeppesen 2019), it is possible for weak audit functions to enable corruption to persist unchecked. Badara and Saidin (2013) summarise how an ineffective internal audit may contribute to: the persistence or emergence of corruption; low or non-compliance with internal control frameworks; and problems in controlling financial operations and decisions within an organisation.

The literature describes how cases of “audit failure”by multinational accountancy firms hired to perform audits of public or private entities can enable corruption and other forms of malpractice (Spotlight on Corruption 2020; Christensen 2020). For example, the firm Deloitte paid a US$80 million settlement to the government of Malaysia following allegations its auditing of the financial statements of 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) helped enable the international corruption scheme associated with the fund.

Shore (2018) argues these firms may adopt corruption narratives as a market-making strategy rather than intending to undertake meaningful audits(Shore 2018). Similarly, Ehrmann and Prinz (2023) explain that as such firms are hired and paid by the body they are auditing, their independence may not be guaranteed, creating risk of “shallow and fraudulent auditing”; indeed, evidence suggests that such firms risking losing clients if they expose internal control weaknesses, creating an incentive to conduct audits only in a performative sense (National Whistleblower Centre n.d.).

While generally unexplored in the wider literature, it is possible that similar dynamics may be present with regards internal audit functions in public sector organisations such as the UN, especially where their independence is not safeguarded (this is discussed in more detail in the final section).

Actors within the UN audit system

Multiple actors with audit mandates (internal and external) exist across the UN system. This section provides a primarily descriptive overview of their work, as well as how they fit into the wider system.

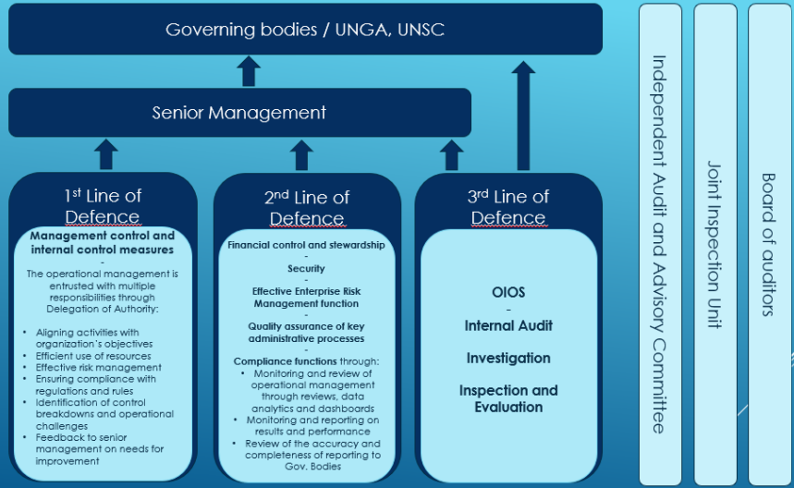

The UN also adopts a “three lines” model. Figure 2 describes how this is translated across various actors:

Figure 2: The UN’s three lines of defence model

Source: OIOS 2023: 4

IIA and Transparency International (2023) summarise responsibilities within the three lines model as follows:

- First line roles: this refers to managers responsible for implementing controls for their organisation’s activity.

- Second line roles: these roles provide complementary expertise to support, monitor and challenge first line managers in their management of risks.

- Third line roles: this role provides independent and objective assurance on the adequacy of governance and risk management, and is fulfilled by internal audits.

- Governing body: a body carries out oversight and is accountable to stakeholders; all three roles have reporting lines to this body.

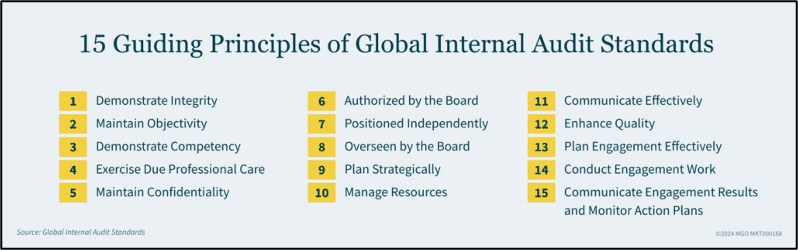

The large majority of UN audit entities also apply the IIA global internal audit standards to their audit functions (Sukari and Terzi 2016). These standards claim to “guide the worldwide professional practice of internal auditing and serve as a basis for evaluating and elevating the quality of the internal audit function” (IIA 2024: 5). As of 2024, the IIA promulgates 15 principles for organisations to adhere to (IIA 2024):24c2567f3e87

Figure 3: IIA’s 15 guiding principles of global integrity standards

Source: O’Rourke 2024

Internal audit actors

Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS)

The OIOS describes itself as the internal oversight body of the UN and is divided into three main divisions: the internal audit division (IAD),d3115fb39b56 the investigations division (ID), and the inspection and evaluations division (IED) (Beigbeder 2021; OIOS n.d.). The IAD “assess the adequacy and effectiveness of internal controls for the purpose of improving the Organization’s risk management, control and governance processes”; the ID “establish[es] facts related to reports of possible misconduct to guide the Secretary-General on appropriate accountability action to be taken”; and the IED “assess[es] the relevance, efficiency, and effectiveness, including impact, of the Organization’s programmes in relation to their objectives and mandates” (OIOS, n.d.). Through these three divisions, OIOS provides coverage to all UN activities under the secretary-general’s authority (OIOS n.d.; KPMG 2022a; b).

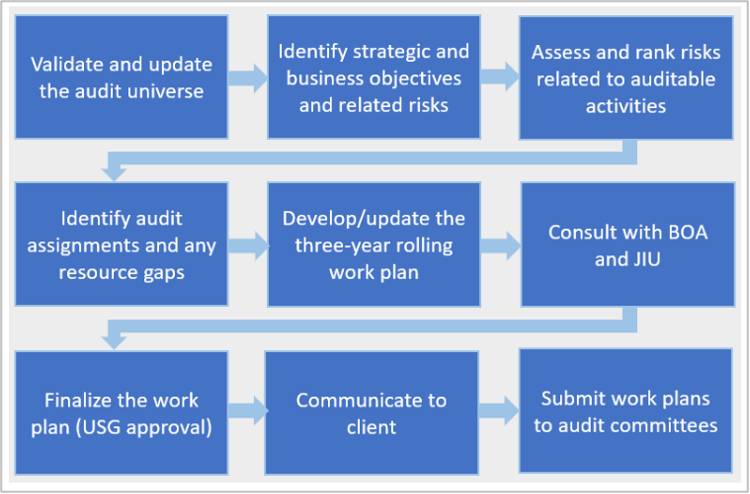

As it pertains to internal audits, the OIOS’ IAD sets annual thematic priority areas which help determine the audits it undertakes (OIOS 2023: 18). Typically, audits are triggered through this annual work plan, which are updated on the basis of systematic risk assessments (OIOS 2023: 14).

Once an audit is selected, an engagement planning process is undertaken to define objectives, scope and methodology for the audit and its subject (OIOS 2023: 21).

Figure 4: The IAD’s engagement planning process

Each audit begins with the issuance of a formal notification memorandum and is followed by consultation with the client, the preparation of terms of reference and the agreement of a final audit plan (OIOS 2023: 22–28). Source: OIOS 2023: 22

Alongside planned work, OIOS retains the authority to conduct ad hoc audits where programme oversight is considered ineffective or there are risks of wasted resources or non-attainment of objectives (OIOS 2023: 2). If, in the course of an audit, it becomes apparent that fraud or misconduct may have occurred, the matter is escalated through IAD management and may be referred to the investigations division (OIOS 2023: 34).

OIOS coordinates with UN oversight bodies such as the board of auditors (BoA) and JIU through regular meetings and joint processes to avoid duplication and strengthen system-wide oversight (OIOS n.d.b). OIOS may also work with other audit and investigation agencies as part of a joint audit or investigation process (see KPMG 2022a).

Entity-level internal audit / oversight bodies

Most UN organisations have their own internal audit or oversight offices (see Sukayri and Terzi 2016). These offices are typically positioned as part of the “third line of defence” in the organisation’s wider governance framework and are designed to provide independent assurance and advice to the executive head and governing bodies on processes of risk management, internal controls and governance.

Much like the OIOS’s IAD, entity-level internal audit bodies apply a risk-based methodology in planning and conducting audits (see UNOPS 2023; UNDP 2024b). For instance, UNDP’s OAI develops a multi-year strategy and annual risk-based plan, and can also launch audits in response to emerging issues (see UNDP 2024b). Here, once an audit is selected, the process may begin with a notification memorandum, followed by an entry meeting to agree scope and timing, fieldwork within the agreed schedule and an exit meeting to discuss preliminary findings. A draft report is then shared with management for comment before the final report is issued (see UNDP n.d.d).

If mandated, entity-level internal audit bodies may also have the authority to conduct investigations into allegations of misconduct (see UNDP 2024b) and, in some instances, as in the case of OAI, audit and investigation functions are combined within these entities (see Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 8; UNDP 2024b).

Although internal audit offices are embedded within individual agencies, they may also coordinate system-wide (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 57). This can occur through joint audits with other audit bodies or through information sharing with external audit bodies and networks such as the BoA, JIU or UN Representatives of Internal Audit Services (UN-RIAS).

Audit and advisory committees

Audit and oversight committees are established to help govern UN entities. They “have a critical role to play as independent expert advisory bodies that provide objective advice and recommendations on… [audit plans and budgets], governance, risk management and internal control processes” (Afifi 2019: iii).

Audit and advisory committee mandates outline varying responsibilities, functions, scope and composition, with varying degrees of independence and reporting lines (Afifi 2019).b8e0fb3d65f8 They provide advice and sometimes oversight, linking audit functions with broader governance mechanisms (Afifi 2019). They coordinate among internal audit, executive management, the BoA and, when appropriate, OIOS and JIU (see Figure 4).

United Nations Representatives of Internal Audit Services (UN-RIAS)

The UN-RIAS is an informal network of internal audit leaders from UN system organisations (UN-RIAS n.d.). UN-RIAS serves as a forum for collaboration and the exchange of expertise among internal audit professionals across the UN system. Its purpose is to strengthen internal audit functions by promoting and supporting good practices (UN-RIAS n.d.).

While recommendations are non-binding, UN-RIAS enables members to discuss emerging risks, audit strategies and innovative techniques, ultimately contributing to greater transparency, accountability and improved governance within the UN system-wide framework (UN-RIAS n.d.).

External audit actors

Joint Inspection Unit (JIU)

JIU is the UN’s only external oversight body and is authorised to carry out inspections and evaluations across the entire UN system (JIU n.d.). JIU’s mandate tasks it with enhancing management and administrative efficiency as well as fostering better coordination among UN agencies and with other oversight entities, both internal and external. JIU assists these agencies in overseeing human, financial and other resources. Through its reports and notes, JIU highlights exemplary practices, recommends benchmarks and promotes the exchange of information among all UN organisations governed by its statute (JIU n.d.a).

United Nations Board of Auditors (UN BoA)

BoA is responsible for externally auditing the accounts and management of the UN, including its various funds and programmes. In addition to its audit functions, the board evaluates the overall administration and management of the entities it audits (UN BoA n.d.a).

BoA issues independent audit opinions in its reports, offers recommendations to those audited, monitors the progress of implementing these recommendations and addresses concerns raised by member states, the general assembly and other relevant parties (KMPG 2022a). The BoA collaborates with various internal audit bodies within the UN to share work plans, management letters and reports, as well as to hold regular discussions and annual meetings on issues of mutual interest (UN BoA n.d.b).

Coordination between internal and external audit actors

In general, the literature recommends interaction and cooperation between the internal auditors and external auditors to avoid duplication and so they can draw insights from each other (ECIIIA 2019: 7; IIA standards).

The UN system generally operates according to the “single audit principle” which means “that one audit, conducted by a qualified and independent auditor, should provide sufficient assurance on the financial statements and the use of funds for all the stakeholders involved”(UNGA 2024: 21). This means that separate donor-commissioned audits of UN entities are typically ruled out (see UNICEF n.d.b). Nicaise (2025) describes how this means the principle means that “internal audit reports become the only realistic channel through which donors can verify whether organisational controls work, risks are managed, and corrective measures are take” although in some cases donors do push and commission third-party audits of UN entities.

While the principle aims to preclude multiple overlapping external audits (which it is argued would create a burden), it crucially does not preclude an external and internal audit from occurring for the same organisation. In many cases, external auditors focusing on the financial statements of UN entities, whereas internal audits and investigations focus on operational processes rather than financial (UNGA 2024: 21).

However, the separation of target areas may not always be so clear. For example, for UNDP activities, the BoA retains the exclusive right to carry out external audits of the accounts, books and statements of UNDP, while the UNDP’s internal audit office – the Office of Audit and Investigations (OAI) – retains the exclusive right to carry out internal audits of the accounts, books and statements (UNDP n.d.b). To this effect, UNDP says that the UN BoA and OAI aim to coordinate their audit activities to avoid any possible duplication of efforts (UNDP n.d.b).

The anti-corruption functions of internal audits

The role of internal audits to counter corruption can be broadly grouped into three main functions: preventive, detective and reactive.8af5717e1ab4 These three functions are described in this section primarily in relation to corruption risks although it should be noted they also target other forms of misconduct. Indeed, while some sources have evaluated internal audits within the UN in a more general sense, there appears to be a significant dearth of literature assessing its effectiveness in addressing corruption specifically.

Preventive

UN audit entities create risk-based work plans and evaluate the effectiveness of internal controls with the aim of ensuring that preventive controls against risks are properly integrated into operational frameworks (OIOS n.d.a; OIOS 2023; UNOPS 2023; UNDP 2024b).

Risk-based audit planning

In the JIU fraud report, Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare (2016) describe how an absence of effective fraud risk assessments, plans and controls creates vulnerabilities for corruption (see also KPMG 2022a: 27).

Within UN entities, risk-based audit planning is a core component of preventive internal audits (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 20). Annual work plans are aligned with organisational goals and adjusted based on risks, trends and other relevant factors (OIOS 2023). Audit directors and section chiefs are responsible for identifying potential fraud schemes and risks, evaluating their likelihood and significance, and setting audit criteria and objectives accordingly (UNOPS 2023; UNDP 2024b). OIOS (2023: 15) outlines the key steps in the annual risk assessment and planning process within their internal audit division (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: OIOS’ risk assessment and work planning process

Source: OIOS 2023: 15

Risk-based plans are designed to ensure that resources are focused on areas most vulnerable to fraud, corruption, inefficiency or non-compliance (OIOS 2023). This includes high-risk areas such as procurement, recruitment, contract management and the use of implementing partners (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016; Sukayri and Terzi 2016). These plans then guide audit decisions and activities across UN organisations to address vulnerabilities in these areas (Sukayri and Terzi 2016). For example, two OIOS audits (2020; 2024a) reviewed procurement activities and resettlement programmes because these areas were flagged in the annual risk assessment as highly susceptible to fraud and corruption.

Internal control framework reviews

Another important preventive measure in UN internal audit activities is reviewing internal control frameworks to protect governance, risk management and other organisational processes (IIA 2019; OIOS 2023) and identify potential gaps to be filled. For example, an OIOS report of the UN’s Financial Disclosure Programme found there were gaps in coverage and many UN staff members are not obliged to declare their financial interests to avoid possible conflicts of interest (Fillion 2024).

In practice, auditors review documents such as past audit reports, board minutes and policy manuals, and interview staff to gain an understanding of operational processes (IIA 2019). Auditors also provide senior management with assessments of control effectiveness and recommend formal control frameworks where gaps are found. In addition, internal audits review organisational policies – such as those covering staff compensation, performance evaluation and accountability – to ensure they are strong enough to prevent misuse or mismanagement of resources (IIA 2019).

Detective

Detective mechanisms within UN internal audit functions are designed to uncover errors, fraud and irregularities after they occur, while also testing the effectiveness of preventive controls (Sukayri and Terzi 2016). However, if audit agencies lack investigation capacity, access to data, resources, independence or effective staff training, their ability to uncover irregularities after the fact is compromised (see Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016; KPMG 2022a).

Auditors can use both manual and computer-assisted tools to review financial and operational transactions for signs of misuse, as well as to check that organisational resources are being properly used and protected (IIA 2019). In the UN context, these evaluations rely on a broad range of information sources, such as resolutions and documents from governing bodies, management reports, budgets, staffing tables and enterprise resource planning systems (OIOS 2023).

In practice, these methods may allow auditors to detect corruption or corruption risks by identifying when established controls are bypassed. For example, audits have detected a case where procurement evaluation criteria were altered after bidding had finished (see OIOS 2024a: ii).

Detective functions also reinforce preventive controls by reviewing their effectiveness in practice. For example, auditors assess how organisations promote ethics and values internally and with external partners, reviewing codes of conduct, anti-fraud and whistleblowing policies, hotlines and training processes, and using surveys or interviews to measure staff awareness of ethical standards (IIA 2019). Similar methods are used to review internal control frameworks. For example, auditors might evaluate how effectively risk and control information is communicated by examining memos, emails and meeting records (IIA 2019).

Detective functions target corruption directly by identifying weaknesses in governance systems, procurement evaluations, fraud risk assessments and reporting structures (see OIOS 2020; 2024a). By making visible the failures of preventive mechanisms, they expose how corruption risks are left unmanaged. For example, audits have found training plans that overlooked corruption risks, such as an absence of conflict-of-interest safeguards (see OIOS 2024a)

Reactive

Reactive internal audit activities focus on responding to risks after they have been identified, such as actions taken to address risks that have already materialised, where the organisation is responding to an incident or failure that has occurred (IIA 2019).

However, allegations of corrupt behaviour go unaddressed if audit follow-up is slow, under-resourced or procedurally weak (see Foltyn 2024b). Furthermore, where whistleblower allegations are mishandled or ignored, it undermines the audit system in its reactive role as further reporting is discouraged and systemic risks are left unaddressed (see KPMG 2022a; Foltyn 2024b; JIU 2016b)

Responding to allegations of fraud and corruption

Collaboration between audit and investigation departments and agencies within UN entities is typically triggered when misconduct is suspected or identified (OIOS 2023). Cases may arise from whistleblower allegations, hotline reports, issues uncovered during routine audits or external allegations reported in the media (see Biryabarema 2018; Foltyn 2024a).

While investigative units lead on case management, internal audits provide critical support through risk-based analyses, testing controls and identifying systemic weaknesses that may have enabled the misconduct (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016; Sukayri and Terzi 2016). In some cases, as outlined above, investigation and audit functions and departments are combined within UN entities, which some UN personnel argue improves internal collaboration (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 8). Between 1 July 2024 and 30 June 2025, the OIOSissued 144 investigation reports, 25 per cent of were identified as relating to fraud and corruption; during the same period, it reviewed 50 reports relating to suspected procurement fraud where issues including procedural irregularities, bribery and kickbacks and undeclared conflicts of interest.

Some internal audit bodies have the mandate to go even further through, for example, referring cases to national authorities to consider launching criminal investigations (although this may be dependent on the revocation of privileges and immunities of UN staff) (UNODC n.d.: 98).

Recommendations and corrective action plans

When audits uncover issue – for example, gaps in an audited body’s corruption risk management approach - recommendations are formally recorded and assigned to relevant departments (IIA 2019; OIOS 2023; UNDP 2024b; UNOPS 2023). These recommendations are prioritised by their level of risk and impact, and management is required to develop corrective action plans to address them (OIOS 2020; 2023). Recommendations can arise as both a response to an existing risk or as means to prevent a likely risk from occurring, positioning the process as both a reactive and preventive mechanism.

Progress and evidence are monitored and reviewed by auditors, advisory bodies or other relevant departments to assess whether corrective actions have been effectively implemented (IIA 2019). For example, OIOS systematically follows up on recommendation implementation by requiring entities to provide documentary evidence before closure (OIOS 2024c). In its 2025 reporting, it tracked all critical and important recommendations issued since 2013, distinguishing those fully implemented from those overdue or in progress (OIOS 2025a). In addition, audit entities may conduct dedicated follow-up reviews, reassessing earlier recommendations for their continued relevance and testing whether corrective actions have been implemented in practice (see OIOS 2024c).

The three functions in practice

The different actors outlined in the previous section are involved in carrying out these preventive, detective and reactive functions to varying degrees (see Table 1 for an overview).

Table 1: The role of UN audit actors as they relate to preventive, detective and reactive functions

|

UN audit body |

Preventive |

Detective |

Reactive |

|

OIOS |

Yes – risk-based audit planning, internal control reviews, policy assessments. |

Yes – internal transaction reviews, ERP/data analysis, investigations into corruption/misconduct. |

Yes – inspections, evaluations and internal after-the-fact audits. |

|

Agency level |

Yes – internal audits, risk-based planning, strengthening internal controls. |

Sometimes – internal audits can detect irregularities; if investigation units exist, may pursue cases of corruption/misconduct. |

Sometimes – conducts investigations if within mandate; otherwise, issue recommendations and monitor corrective action. |

|

Committees |

Yes – oversees and advises on governance, risk management and audit frameworks. |

No – mainly performs advisory roles; do not conduct audits. |

Yes – reviews and follows up on audit recommendations. |

|

UN-RIAS |

Yes – promotes harmonisation, capacity building, sharing good practices. |

No – does not conduct audits or investigations. |

Sometimes – provides recommendations and guidance to strengthen follow-up actions, but no direct investigation or enforcement role. |

|

JIU (external) |

Yes – reviews UN system-wide audit and oversight functions. |

No – does not audit directly. |

Limited – produces thematic/system-wide reviews and recommendations but no enforcement. |

|

BoA (external) |

Yes – recommends improvements to governance and financial management. |

Yes – performs external financial and operational audits. |

Yes – external financial and operational audits, after the fact. |

Source: author’s own analysis of respective bodies’ functions

As described above, there is a lack of source (internal to the UN and from external observers) which address the effectiveness of internal audit bodies within the UN in addressing corruption specifically.

While not attesting to their effectiveness, examples of publicly available internal audit reports suggest that in practice they may consider corruption risks and make recommendations which aim to mitigate them. Two examples of internal audits led by OIOS are described below; a selection of findings and recommendation are highlighted and grouped under the three anti-corruption functions.

OIOS audit of UNHRC

In 2020, the OIOS published its audit of the prevention, detection and response to fraud committed by persons of concern in the context of resettlement activities at the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHRC) (OIOS 2020).

Preventive

OIOS included the audit in its 2019 risk-based plan because of the high vulnerability of UNHCR resettlement processes to fraud and corruption. The audit assessed how UNHCR had implemented its 2017 Policy and Operational Guidelines on Addressing Fraud Committed by Persons of Concern,which were designed to strengthen preventive controls against fraud and corruption (OIOS 2020: 2).

Detective

The audit methodology involved interviews with staff, examination of documentation, analytical reviews of systems, tools and datasets, and testing of 55 fraud and inconsistency cases. It also included the observation of resettlement interviews and an assessment of anti-fraud messaging and complaints channels (OIOS 2020: 2).

The audit found gaps in fraud governance and controls: some operations had not formally designated anti-fraud focal points or had misaligned roles and reporting lines; fraud risk assessments and communication channels were out-of-date or incomplete; and most offices did not systematically record or analyse fraud cases. Case handling was inconsistent, with variable quality and timeliness in investigations, and disclosures of confirmed cases to resettlement countries were also inconsistent and in one case inappropriate (OIOS 2020: 2–9).

Reactive

OIOS issued three recommendations: (1) strengthen the fraud accountability framework by clarifying roles, reporting lines, segregation of duties and introducing templates for anti-fraud focal points; (2) reinforce oversight of the fraud policy and guidelines through remote monitoring and regional offices; and (3) promote the systematic use of fraud reporting, recording and analysis mechanisms. UNHCR accepted the three recommendations and reportedly began implementation (OIOS 2020: 5–10), but this review of the literature was unable to locate evidence of completion at the time of writing.

OIOS report of MONUSCO

In 2024, the OIOS published its audit of procurement activities in the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO).

Preventive

Due to its high vulnerability to fraud and corruption, OIOS, as part of its 2023 risk-based plan, audited MONUSCO’s procurement activities and internal control frameworks (OIOS 2024a).

Detective

The audit applied a detective methodology, interviewing personnel, assessing data management practices and procurement data, and reviewing 41 solicitations and reports.

The audit identified lapses in the technical and commercial evaluation of offers, incomplete risk assessments that overlooked fraud and corruption risks, inadequate training and conflict-of-interest safeguards for staff, and incomplete staff certification and distribution of mandatory procurement courses (OIOS 2024a).

Reactive

OIOS issued seven recommendations, all accepted by MONUSCO, with one implemented and the rest still to be actioned at the time of writing, subject to ongoing monitoring. One recommendation was that MONUSCO enhance the integration risks of fraud and corruption into procurement selection processes (OIOS 2024a).

MOPAN (Multilateral Performance Network) assessments

The MOPAN (Multilateral Performance Network) is a network of 21 members (largely donor countries) which carries out independent assessments of multilateral organisations, including UN entities. Their assessments up until the end of 2025 have been based on MOPAN methodology MOPAN 3.1; under this approach, assessments “draw upon different streams of evidence (documents, survey, interviews) from internal and external sources to validate and triangulate findings against a standard indicator framework” (MOPAN 2020d).

Grouped under the category of “[o]rganisational systems are cost- and value-conscious and enable transparency and accountability”, three of these key performance indicators (KPIs) measure the effectiveness internal audit, internal controls and corruption prevention (MOPAN 2020d):

- KPI 4.4: External audits or other external reviews certify that international standards are met at all levels, including with respect to internal audit

- KPI 4.5: Issues or concerns raised by internal control mechanisms (operational and financial risk management, internal audit, safeguards etc.) adequately addressed

- KPI 4.6: Policies and procedures effectively prevent, detect, investigate and sanction cases of fraud, corruption and other financial Irregularities

For each indicator, MOPAN gives the assessed multilateral agencies one of the following scores:

- Highly satisfactory

- Satisfactory

- Unsatisfactory

- Highly unsatisfactory

- No evidence/not applicable

Table 2 summarises the scores given for these three KPIs as part of assessment reports of UN entities conducted by MOPAN.2cac08163c49

Table 2: Overview of scores against KPIs 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6 given under MOPAN assessments of UN bodies

|

Assessed UN entity |

Source/ Year of assessment |

KPI 4.4 |

KPI 4.5 |

KPI 4.6 |

|

Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) |

2024a |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) |

2024b |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

International Labour Organization (ILO) |

2021a |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) |

2024c |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) |

2021b |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) |

2020a |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) |

2020b |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) |

2025a |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

UN Women |

2025b |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) |

2021c |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) |

2019a |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

UN Habitat |

2024d |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) |

2019b |

Satisfactory |

Unsatisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) |

2021d |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) |

2020c |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) |

2019c |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

|

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) |

2024e |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

Highly satisfactory |

|

World Health Organization (WHO) |

2024f |

Highly satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Highly Satisfactory |

Source: compiled by author based on MOPAN reports

This overview suggests that MOPAN positively assesses the robustness of most UN entities’ audit, internal control and corruption prevention functions. In no assessment was a “highly unsatisfactory” score given for the three corresponding indicators, and in only one case (UNIDO) was an “unsatisfactory” score given; for KPI 4.5, MOPAN found that UNIDO internal policies were unclear as to how issues identified through internal control mechanisms were to be addressed.

At the same time, these assessments and scores do not appear to align with evidence from other sources. Notably, UNDP and UNOPS received “highly satisfactory” scores for all three KPIs, but as covered elsewhere in this section, both have faced allegations and cases of fraud or corruption (which surfaced after the assessment reports were published). Nevertheless, in its assessment of UNDP, MOPAN found there was an effective risk-informed approach in place used to detect fraud and corruption issues (MOPAN 2020b). Similarly, for its assessment of UNOPS, MOPAN found the organisation had institutionalised “investigation and anti-fraud and -corruption processes and practices, with cases of misconducted effectively explored, concluded and reported, including to the governing bodies” (MOPAN 2021c).

Weaknesses and good practices

While the previous sections have largely outlined the system as it should operate, how internal audits within the UN system work in practice can differ. A survey of the literature suggests the efficiency of internal auditing is highly contingent on the presence of various factors. This section describes these, and presents examples of weaknesses and, for each, again draws from the two recent cases and the wider literature.

Operational independence

IIA (2019: 29) defines independence as “freedom from conditions that threaten the ability of the internal audit activity to carry out internal audit responsibilities in an unbiased manner”. The IIA standards (2024) also emphasise that a defined relationship between audit and oversight committees and the governing bodies is crucial to an effective and independent audit function.

The JIU audit report emphasises institutional independence as a crucial attribute for audit bodies and oversight committees (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 12–13). Separation from executive control is a significant aspect of what defines operational independence in practice. Sukayri and Terzi (2016: 13) argue that independence in the UN system can be secured when an internal audit has direct access to the highest level of management and maintains a functional reporting line to the governing body. Similarly, the IIA (2024: 47) note “a direct reporting relationship between the board and the chief audit executive enables the internal audit function to perform internal audit services and communicate engagement results without interference or undue limitations”.

However, in practice, even if independence is formally mandated, these safeguards are not always upheld. Beigbeder (2021) highlights how the investigations division of the OIOS does not have an independent budget, but is in fact funded by the very organisations it investigates. They warn this can lead to conflicts of interest which threaten to undermine the investigation. Afifi (2019: 11) found that for six UN entities, “the audit and oversight committees’ terms of reference or charter is approved by their executive head only”.ccbc587d4c6d Recent reviews reveal this is still the case for four of the six organisations (see Fernández Opazo 2023; UNDP 2024d; UN-Women 2023; UNICEF n.d.a). Additionally (Afifi 2019: iv) found that in most cases these committees’ terms of reference or charter lacked any conflict-of-interest guidelines.

In the S3i case, investment decisions were centred around the executive director’s (ED) and deputy executive director’s interests. IAIG identified risks in investment decisions, but lacked the mandate to investigate senior leaders, undermining its operational independence. Additionally, as mandated in UNOPS’s IAIG’s charter, IAIG is supposed to have “free and unrestricted access to the Executive Board and the Audit Advisory Committee” (UNOPS 2022: 4; KPMG 2022a). However, a review of its independence revealed that such access was not defined as there exists no clear policy outlining whether the director of IAIG could access the executive board without informing the executive director or without management present (UNOPS 2022). The review further highlights that management has frequently infringed on the IAIG’s oversight functions.3cd8ce49427f

KPMG (2022a) also found UNOPS’s audit advisory committee (AAC) did not fulfil an effective oversight function. Members of the AAC were appointed by the ED, and the role of the AAC in advising the ED was based primarily on information received from the ED himself, meaning the AAC essentially functioned as an extension of management interests, according to KPMG (2022a).

In the FFS case, despite the OAI being described as “completely independent” (Foltyn 2024a), criticisms note that the OAI reports to senior management. Additionally, the mandate of OAI appeared to be restricted. For example, a self-assessment review of the UNDP’s OAI’s independence found the “OAI currently has no access to the Executive Group, which is UNDP's highest internal governing body”; does not receive minutes from executive group meetings; and “does not attend the meetings of the… UNDP Risk Committee” (OAI 2022: 12).

Good practice

Referring to the S3i case, Nicaise and Fanchini (2025: 26) find that “[i]nternal audit and investigative units perform best when structurally independent from executive leadership, thereby minimising conflicts of interest” and that instead they should report to independent governance bodies, such as executive boards or audit committees with enforcement powers

The framework in the UN Population Fund’s (UNFPA) oversight body, the Office of Audit and Investigation Services (OAIS) can be considered good practice in this regard. In line with IIA standards, UNFPA’s oversight policy and OAIS charter guarantee unrestricted access to the executive board (UNFPA 2022). The director of OAIS engages directly with the board through closed meetings and briefings on potential red flags, audit findings and the status of investigations.

Good practice is also seen at the World Food Programme (WFP) where their audit committee functions as a governing body adviser, is established by the executive board and reports to both the governing body and executive director (see WFP 2018: 5). Sukayri and Terzi (2016: 43) emphasise this as good practice and note that this framework enables WFP’s audit committee to ensure “the effectiveness of WFP’s internal control systems, risk management, audit and oversight functions and governance processes… [and strengthens] accountability and governance within WFP”.

Resourcing

Sukayri and Terzi (2016: iv) note that as of 2016, many internal audit bodies faced resourcing challenges:

‘…many stakeholders across the United Nations system are of the opinion that internal audit budgets are inadequate. Lack of funding limits the ability to hire qualified staff necessary to conduct high-quality audit work. It also restricts the ability to conduct a sufficient quantity of high-quality audits to address the high-risk areas identified in the internal audit plan.’

The aforementioned independence review of the OAI concluded that while OAI had the mandate to conduct proactive investigations, “this has not been possible due to limited resources in dealing with a disproportionate caseload” (OAI 2022: 10). Similarly, the IAIG independence review found the IAIG does not have sufficient resources to effectively investigate its caseload (UNOPS 2022).

Additionally, in accordance with IIA (2024) standards, auditors are required to undertake continuous professional education on an annual basis. However, a review of UNOPS’ IAIG found that “IAIG does not have a separate budget for this kind of training [and]… in terms of resource allocation, the current UNOPS rules do not allow [for free] transfer of resources within budget lines” (UNOPS 2022: 7).

Good practice

Sukayri and Terzi (2016: vii) find “executive heads of [UN] system organisations… should allocate adequate financial and human resources to the internal audit services to ensure sufficient coverage of high-risk areas and adherence to established auditing cycles”. Again, the framework in UNFPA’s OAIS may constitute a good practice in this regard. For example, OAIS is given the ability to deploy savings from certain line budget items to areas where funding is most needed (UNFPA 2022).

Coordination

Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare (2016: 73) found that oversight functions across the UN system face coordination challenges and that “information-sharing, among the different oversight functions (audit, investigation, inspection and evaluation) needs to be further improved within the organisation to effectively combat fraud”. For example, they cite reported cases where internal audit reports had identified red flags for fraud, but due to poor communication practices between internal audit and investigation bodies, no investigation was launched (although they noted this issue was less pronounced where internal audit and investigation functions were performed by the same UN internal oversight office (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016: 73). Similarly, Sukayri and Terzi (2016: 60) highlighted a number of practical issues that relate to the process of joint audits and said the UN “lacked a unifying governance structure and a central support framework for joint audits”.

In the S3i case, after the OIOS received a whistleblowing complaint in 2019, OIOS transferred the responsibility to investigate the complaint to the IAIG and the deputy executive director. However, as the IAIG was not mandated to investigate the executive director and deputy executive director, the complaint was not investigated by either the OIOS or IAIG, reflecting a poorly executed information sharing function (KPMG 2022a). Furthermore, in their review, KPMG (2022a) found that red flags in S3i activities were scattered across various channels and oversight bodies. KPMG (2022a) note that this fragmentation made it difficult to coordinate an effective response.

KPMG (2022a: 34) further observed that communication failures extended to an external audit. Although the BoA flagged risks related to S3i and loan provisions in 2019 and 2020, these warnings were not reported on in the 2020–2021 annual report.

Good practice

Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare (2016) recommended that UN entities include updates on the implementation of and coordination between different internal oversight activities in their reports to legislative and governing bodies. IIA standards also require internal audits to implement effective information sharing mechanisms with external auditors to ensure proper coverage and to avoid duplication (Sukayri and Terzi 2016: 29).

Sukayri and Terzi (2016: vi) emphasise the importance of developing a comprehensive audit strategy that ensures the effective function of joint audits and point to UN-RIAS as an effective means to achieve this. UN-RIAS (2014) have developed a joint audit framework to serve as a basis for harmonising the joint audit process. An example by UN-RIAS (2019) highlights effective use of this framework for the Joint Internal Audit of Delivering as One in Papua New Guinea. The use of the UN-RIAS framework meant the six agencies involved applied a successful harmonised audit approach.

Transparency and disclosure

Multilateral organisations may elect not to publish details of its audits or investigations into misconduct (Bergin 2023). Nicaise and Fanchini (2025: 25) describe how multilateral organisations’ approaches towards disclosure range from unfiltered transparency (which carries risks) to “strategic opacity” (where information sharing is delayed, selective or partial); in between both, there is “balanced disclosure” in which the openness is upheld with a degree of justified oversight. However, in practice access to internal audits may be inconsistently granted, including for donors (Nicaise 2025).

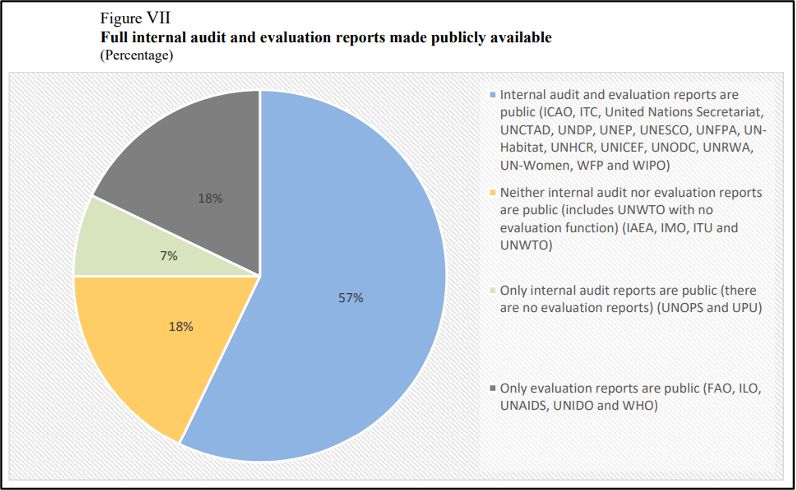

Lozinskiy (2023) analysed the different disclosure policies of UN entities as part of a study commissioned by JIU and found some 36 per cent of them did not publicly disclose their internal audit reports (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Differences in UN entities’ disclosure policies for internal audit and evaluation reports according to 2023 JIU report

While in some cases this can be justified (for example, Sukayri and Terzi (2016: 62) describe how disclosure might reduce the likelihood of open responses from subjects of internal audits), in others it restricts the potential impact of internal audit reports. For the FFS case, Foltyn (2024a) notes how donors found it difficult to monitor how their contributions were actually spent, and internal reports and monitoring documents did not accurately reflect the project’s real activities. This lack of transparency hinders the ability to assess whether good practice is reinforced and resources are managed appropriately and aligned with intended objectives.

Good practice

Sukayri and Terzi (2016: 47) emphasise good practice in audit and oversight through the public disclosure of audit reports. Disclosure provides confidence to external stakeholders, especially member states and donors, by increasing transparency around risk management and oversight. If findings and recommendations are transparently disclosed, this openly strengthens accountability and improves the quality of reporting and governance functions.

Within UNDP, the OAI has made its internal audit reports accessible online since 2012 (UNDP n.d. c)

Follow-up to red flags and recommendations

Internal audit reports may recommend potentially effective measures preventing, detecting or reacting to corruption or fraud, but no follow-up or implementation is undertaken by the audited body to ensure these are translated into action (Newman et al. 2019). A lack of systematic follow-up on audit recommendations and red flags may be explained in part by the other factors described in this section, such a lack of independence for entities and resourcing constraints (see Sukayri and Terzi 2016).

In addition to the events already outlined, KPMG (2022a) found that a recommendation to strengthen the audit advisory committee (AAC) in compliance with JIU good practice had not been effectively or appropriately implemented.4f6ceb3be07a

Good practice

Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare (2016: 73) argue that where red flags have been detected by internal audits in the UN, an investigation should be considered as a next step.

In terms of recommendations from reports, Sukayri and Terzi (2016: 48) emphasise that it is “leading practice to have a centralised unit or mechanism that coordinates follow-up and reporting”. Afifi (2019: 26) argues for UN entities’ audit and oversight committees to monitor and follow up on the implementation of all recommendations of internal and external audits. A good practice was noted at WFP, which has established a central unit to follow up and report on recommendations made by internal audits, external audits and JIU. An external review of WFP by MOPAN (2024g:59) found: “[r]ecommendations from audits and reviews are followed up and there is a high level of sign-off of completed recommendations”.

OIOS has an automated database which collects various kinds of information regarding the recommendations it issues in its internal audit reports, which it states enables it to monitor the status of their implementation (OISO 2023: 43).

- These five enablers were identified inductively by the author upon reviewing the two cases and the wider list of sources.

- Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare (2016) note that: “‘fraud’ and ‘corruption’ are often lumped together and sometimes used interchangeably in the reports and documents of the United Nations system as well as in the literature of other public and private domains. Although there are instances where a particular conduct may constitute both fraud and corruption [sic] it should be noted that as a legal matter the concepts remain distinct”.

- Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare (2016) and Sukayri and Terzi (2016) authored two Joint Inspection Unit (JIU) reports on fraud detection and response and the audit functions within the UN system respectively. The purpose of these reports is to provide an independent examination of these functions within the UN system, and – while dated – they are the most recently available of such reports. The JIU is the only independent external oversight body of the UN system and is described in further detail in the following sections.

- For a more detailed overview of UN whistleblowing systems, see Maslen, C. 2021. Whistleblower protection at the United Nations.

- As of the time of writing, responses to the S3i case are ongoing; for example, UNOPS has engaged the United Nations Office of Legal Affairs to lead the efforts to recover funds from the S3i programme.

- The UN’s definition of an internal audit maps very closely to the IIA one: “[t]he internal auditing function is an independent and objective assurance and advisory activity designed to add value and improve the UN's operations. Internal audits help the UN to accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to assess and improve the effectiveness of governance, risk management and control processes” (OIOS n.d.).

- The IIA global internal audit standards gives a more detailed breakdown of what these principles entail, as well as examples of conformance.

- For a more detailed overview of how the internal audit division is structured, see OIOS (2023: 5).

- For example, the Independent Audit Advisory Committee (IAAC) serves as the oversight committee for OIOS. Agency-level internal audit bodies have their own committees.

- This grouping of the three anti-corruption functions is based on the author’s own analysis. This literature review was unable to locate any internal UN sources which describe in an equivalent level of detail how internal audit is intended to address corruption.

- In the respective MOPAN assessment reports, justifications for each score is given. The reader is invited to consult the reports listed in the reference list for further detail.

- These are UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNOPS, UNRWA and UN-Women.

- “…management has asked IAIG to change which offices it audits, and when audits are held, and even to switch the nature of some engagements from assurance to advisory. In other cases, auditees have sought to question IAIG’s sampling approach, its methodology, and which samples the auditors selected for testing” (UNOPS 2022: 6).

- “The JIU recommended the [executive board] to adopt a revised Terms of Reference prepared by the ED for the AAC in compliance with good practices and established standards. The executive board at that time noted the management response, the three newly appointed members to the AAC, the merger of the AAC and the Strategic Advisory Group, and that the recommendation was considered implemented and closed. In KPMG’s view, the implementation of the recommendation did not resolve all issues observed by the JIU” (KPMG 2022a: 41).