Examining the link between gender and corruption

For nearly two decades, the development community has debated whether there is a systematic relationship between gender inequality and corruption. The debate started in 2001 with the publication of two studies that explored the correlation and concluded that lower levels of corruption were associated with a higher number of women in national parliaments, as well as in public office and in the labour force generally.fe5dde567171 The studies were based on an analysis of data from the World Bank’s gender equality index and Worldwide Governance Indicators.a416e125fe03 They attracted some controversy: to some critics, the findings seemed to imply the dubious notion that women were inherently less corrupt than men,fc75753a9033 the ‘fairer and purer sex,’9218af12d410 who could now serve as ‘the new anti-corruption force.’09fb3c31eb7a However, the studies were methodologically sound and had included controls for other explanatory factors such as civil liberties, income, and education. More recent studies have concluded that the relationship between the number of women in public office and the level of corruption depends on regime type, and that having more women in office results in less corruption in democratic but not in authoritarian states.2bff63fe9e92

Some subsequent analyses of the relationship between women’s participation in public life and levels of corruption have resulted in less certainty about the link.a48556793d3c However, a number of recent studies have reasserted that women’s participation in public office, including at the local government level, is associated with a reduction in both petty and grand corruption.5229cf20ce28 Moreover, this association appears firmer in settings where there is greater ‘substantive representation of women’: that is, where women do not just occupy public office but can have their concerns taken seriously, as shown by health expenditure, family-friendly policies, and maternity leave policies.c28e4bfae6a6 Therefore, the reduction of corruption appears to be not a direct effect of having women in office, but rather an indirect effect that happens when female office holders seek to represent women by improving service delivery in areas of concern to them.

Some of the newer studies imply that the relationship might be the other way around, that is, that corruption is an obstacle to women’s participation in public life and thereby contributes to gender inequality.62d905b2354f These studies explain that women are often excluded from patronage systems and clientelist networks due to sexism, that they lack the finances needed to run for electoral office because they earn less than men, and that they find it difficult to be involved in public life because of their family responsibilities and social norms.2a07b9250421

A number of studies have sought to determine whether women are characteristically less inclined towards corruption than men. The conclusion has been that women are indeed more risk-averse and less likely than men to cheat, but we cannot say that women necessarily have more integrity than men, because they are a diverse group.428a7bae1ffb However, women do suffer the effects of corruption more than men because of their lower status in society, their maternal and caregiving functions, and their other household duties such as food preparation and fetching water.c4e916960ce7 The negative effects of corruption are both direct, when women are victims of bribery and sextortion, and indirect, when corruption drains resources that could have been used to improve women’s lives.293f03c3da1c

‘Sextortion,’ and sexual corruption generally, clearly has a disproportionate effect on women and is attracting more attention from researchers. The International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) defines sextortion as ‘the abuse of power to obtain sexual favors.’ac3e70d1af12 It arises from the fact that even when women have no money to pay a bribe, they have something that some men in power want to exploit: their bodies.ec9d95e27b3b In 2019, for the first time, Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer Report on Latin America and the Caribbean covered sextortion, reporting that one in five women had experienced it or knew someone who had.6e652d63dbcc

Following early World Bank studies on gender and corruption, the Bank has held a longstanding policy that increasing women’s participation in the public sphere can improve adherence to the rule of law and good governance.ac78e1391b1f However, gender and women’s rights activists decry such an instrumentalist approach to women’s participation, which, they emphasise, should be based on women’s human right to participate in public life as guaranteed under Article 7 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).142422d8711b Moreover, increasing the number of women in public office as a means of reducing corruption runs the risk of promoting a meaningless ‘add women and stir’ approach, as well as reinforcing gender stereotypes about women’s self-sacrificing nature and risk aversion.

Few studies have examined the relationship between women’s participation and corruption at the sectoral level. This is true for the forestry sector as well. As a result, ongoing efforts to reduce corruption in the forestry sector often disregard the importance of gender, while efforts to integrate gender into forestry activities do not necessarily consider corruption as a major obstacle to forest conservation and gender equality. For instance, a comprehensive analytic toolkit on wildlife and forestry crime does not consider gender issues,9b6a6e66e5fe and a recent compilation of seminal articles on gender and forestry considers corruption issues only tangentially.d4dbc66efc53

This U4 Issue summarises key issues in forestry corruption, gender and forestry, and corruption and gender dynamics in the forestry sector. It concludes by calling for a gender-sensitive forest governance framework that promotes gender equality as well as transparency, accountability, and integrity in order to conserve forests, thereby helping to slow forest degradation that contributes to climate change.

Corruption in the forestry sector

There is a strong link between corruption and deforestation. A 2009 study that analysed several corruption indices and annual rates of deforestation found a substantial connection between poor corruption control and a high rate of deforestation.8338c84ebb4c Several prior studies had produced similar findings, and more recent reviews confirm the correlation.a35313f48833 Indeed, corruption, ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain,’10569fcc8b8d manifests in the forestry sector mainly as illegal logging, which strips forest cover. This has implications for global efforts to control climate change, since forests help stabilise the climate by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.b93a548fcd0d However, corruption in this sector can also involve fraud and diversion of funds in forestry conservation schemes such as REDD+. Yet another form of forestry corruption is elite capture of community forestry management projects. We will look at each of these briefly in turn.

Illegal logging

Illegal logging refers to timber harvesting–related activities that are ‘inconsistent with national and sub-national law,’ and it ranges from illegal logging in protected areas to obtaining concessions illegally.bf0e684488c5 It may also involve cutting protected species, cutting above the allowable cut, and cutting undersized trees. Forestry crime more broadly includes illegal hunting and poaching and illegal gathering of non-timber forest products, but these will not be considered in detail here.1b4aff7bdd8a Along the timber supply chain, illegal logging is often associated with other types of wrongdoing, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Illegal logging and associated offences at origin, transit, and destination points

| Forest offences | Associated activity | |

| Origin |

Illegal logging and harvesting |

Corruption |

| Transit |

Illegal import |

Corruption |

| Destination |

Illegal import |

Corruption |

Source: Adapted from UNODC (2012), p. 35.

Research has highlighted that corruption in the forestry sector is driven by weak governance and law enforcement, on one hand, and by the significant amounts of money to be made from forests and trees, on the other.b1ebe681d1de The remoteness of forests ‘provides rich opportunities for plunder away from public scrutiny.’d4b0f0bf7b77 In Indonesia, a study by the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission found that 77 to 81% of wood production at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry was not recorded. As a result, the state suffered a loss of non-tax state revenues worth approximately USD 377 to 520 million per year during the study period (2003–2014). Similarly, the state loses up to USD 870 million to USD 1.2 billion per year from commercial timber production.e54ca927757c According to Interpol, illegal logging accounts for 50–90% of all the timber harvested in some tropical producer countries and for 15–30% globally. The economic value of global illegal logging, including processing, is between US$30 and US$100 billion, or 10–30% of global wood trade.f8eeedc6e3a6 The result is widespread deforestation and forest degradation.

Corruption opportunities through bribery and extortion abound at various stages of the forestry supply chain, from the design and award of concessions through operation and logging, transport, processing, export, and sale. Bribes are paid to obtain harvesting licenses, to secure clearance from local (subnational) governments to fell trees, to enable transporters to pass checkpoints, to export or import timber, and to evade taxes.fd0286964bbb A KPK Indonesia study on corruption in licensing processes in the Forestry Sector found that processes were tainted by corruption starting right from the planning process through to the supervision of licensing concessions. The study found that processes were vulnerable to bribery, gratification, abuse of authority and state capture. The unofficial licensing fees varied from about IDR 600 million to 22 billion (equivalent to USD 43,000 to 160,000).6c42880a7968 Many of the world’s forests are located in countries where corruption is rampant, as evidenced by their poor scores on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. Indeed, some scholars have demonstrated that the ‘resource curse’ (little or no economic growth despite the presence of resources) exists in regard to forests too, because this valuable resource is a source of huge rents for political elites, who divert the money that could be used to fund public services into their own pockets, creating a vicious cycle of deforestation.0b017797c761 However, corruption in forestry is not just a developing country problem, as developed countries that perform well on the Corruption Perceptions Index, such as Canada, have also reported widespread illegal logging.891726c7d0cf

Fraud and misappropriation in forestry conservation programmes

With such strong incentives for corruption in the sector, it is perhaps not surprising that corruption has been reported in forestry conservation schemes such as REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation). REDD+ is a global climate-change mitigation scheme that employs a performance-based mechanism in which forest stakeholders from household to national level stand to be rewarded for protecting or enhancing the carbon sequestration capacity of forests. Research by the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre on REDD+ cautioned that the scheme would create new incentives and opportunities for corruption in a sector already riddled with it.e6b895684e00 A later case study on the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) indeed identified several corruption risks that were occurring. They included kickback payments and favouritism in the award of consultancy contracts, per diem abuses in REDD+ events, the politicisation of government forestry positions, and financial mismanagement by international development cooperation agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) entrusted with REDD+ funds.73485d667bbe Further research by U4 identified corruption potential in the design of benefit-sharing mechanisms, identification of beneficiaries, verification of data, and management of revenues.78f62515b0e1 A corruption risk assessment of REDD+ in Kenya identified similar concerns: that REDD+ funds would be embezzled, that data and results would be manipulated, and that the scheme would create incentives for land grabbing by elites.43959abd4403 Not much research has been done on whether the fears about corruption in REDD+ are being realised, although the papers mentioned above discuss the potential problems and pitfalls.

Elite capture

Elite capture was observed in a study of conservation projects in the village of Ladang Palembang in Lebong District, Bengkulu Province, in Sumatra, Indonesia. The village head and other officials demanded kickbacks from project budgets of up to 20% and extracted illegal payments from community members seeking to access poverty alleviation benefits, such as gas cookers, solar panels, and rice, that were supposed to be free. Cattle were distributed to family members, supporters, and cronies of the village head. Elite capture was enabled by political patronage relationships that had in turn been facilitated by the decentralisation process in Indonesia. This gave local elites (village heads) increased access to resources, but with few checks and balances, allowing them free rein over development projects.88231dc0364c Similar research from Odisha State in India exposed how elite capture further marginalised minority groups who were considered as being of lower caste. They were effectively excluded from a forest rights committee as they were never consulted or involved in making decisions. As a result, they were not granted land titles, while other members of the community benefitted from a new titling initiative.73d344fd8916

Corruption in the forestry sector, then, can take various forms and involve a wide variety of private and public actors, from the community level through to the international level. Corruption does not just result in forest degradation but also contributes to inequality when it excludes some people from the benefits of community development projects or performance-based schemes such as REDD+.

Responses to forestry corruption

To curb corruption in the sector, actors have recognised the importance of an international response. This is because the timber trade is international, and corruption can only be properly addressed through cross-national collaboration. The European Union (EU) Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) process aims to bring together timber-consuming and timber-producing nations to solve problems through bilateral FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPA). A VPA includes commitments and action from both parties to curb trade in illegal timber through a license scheme that certifies the legality of timber exported to the EU. To issue FLEGT licences, VPA partner countries must implement a timber legality assurance system and other measures specified in the VPA. At national level, a timber legality assurance system is achieved through participatory processes involving the government, the private sector, and civil society and includes supply chain controls, mechanisms for verifying compliance, and independent audits.02d6c8d43b20 Indonesia became the first country in the world to issue FLEGT licenses in 2016. Several other timber-producing countries such as Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ghana, Liberia, and Republic of Congo have since signed VPAs as well, while Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand are still in the negotiation stage.0ca652f1d5f9

Corporate codes of conduct adopted by furniture multinationals such as IKEA aim to ensure that the wood they use is not from illegal sources. They require the use of wood-tracking and certification systems to confirm that timber is from well-managed and sustainable forests. However, corporate efforts have so far had a limited impact on curbing illegal logging. There is suspicion, as well, that they are reinforcing corporate control over forests, leading to further unsustainable forest use to serve the profit motives of companies.397d03689b14

Another method being tried is to use satellites to monitor forest cover and thereby improve transparency in the sector. Civil society organisations have put in place independent monitoring mechanisms to curb illegal logging and have been active as whistleblowers on violations of forestry law.1095ef625c7d At national level, efforts are being made to control illegal logging by publishing forest data and allowing civil society organisations to verify it. Communities are being mobilised for forest conservation initiatives, and legal and policy reforms have been undertaken.dd2c6f05b462Unfortunately, illegal logging is still a serious global problem because of the incentives arising from the profitability of timber.

To sum up, illegal logging, usually done in collusion with public officials, is a serious threat to forest conservation and hence to ongoing efforts to control climate change. REDD+ began as a forestry conservation programme but it has become controversial, allegedly creating new opportunities for corruption in a sector that in many countries is already one of the most corrupt. The enormity of the challenge of deforestation and climate change requires us to strengthen existing approaches and find new ways of collaborating to conserve forests and limit global warming.

Gender and forestry

Organisations such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) have, since the late 1970s, recognised the important role of women in the forestry sector and the importance of gender roles and gender equality in relation to trees, forests, land use, and the environment.83480230a875A recently published FAO guide on mainstreaming gender in forestry aims to help forestry technical officers ensure that forestry projects serve women’s needs and work towards gender equality objectives.1554614372a2 The Centre for People and Forests, Climate Investment Funds, and some REDD+ programmes have also published similar guides.293877b6270e

The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) has conducted a review of the substantial literature on gender and forestry. The emerging themes, discussed briefly below, include gender and forest usage, gender and community forestry management, and the intersection of gender, forest conservation, and climate change, including gender issues in REDD+.1222e76672f3

Gender and forest usage

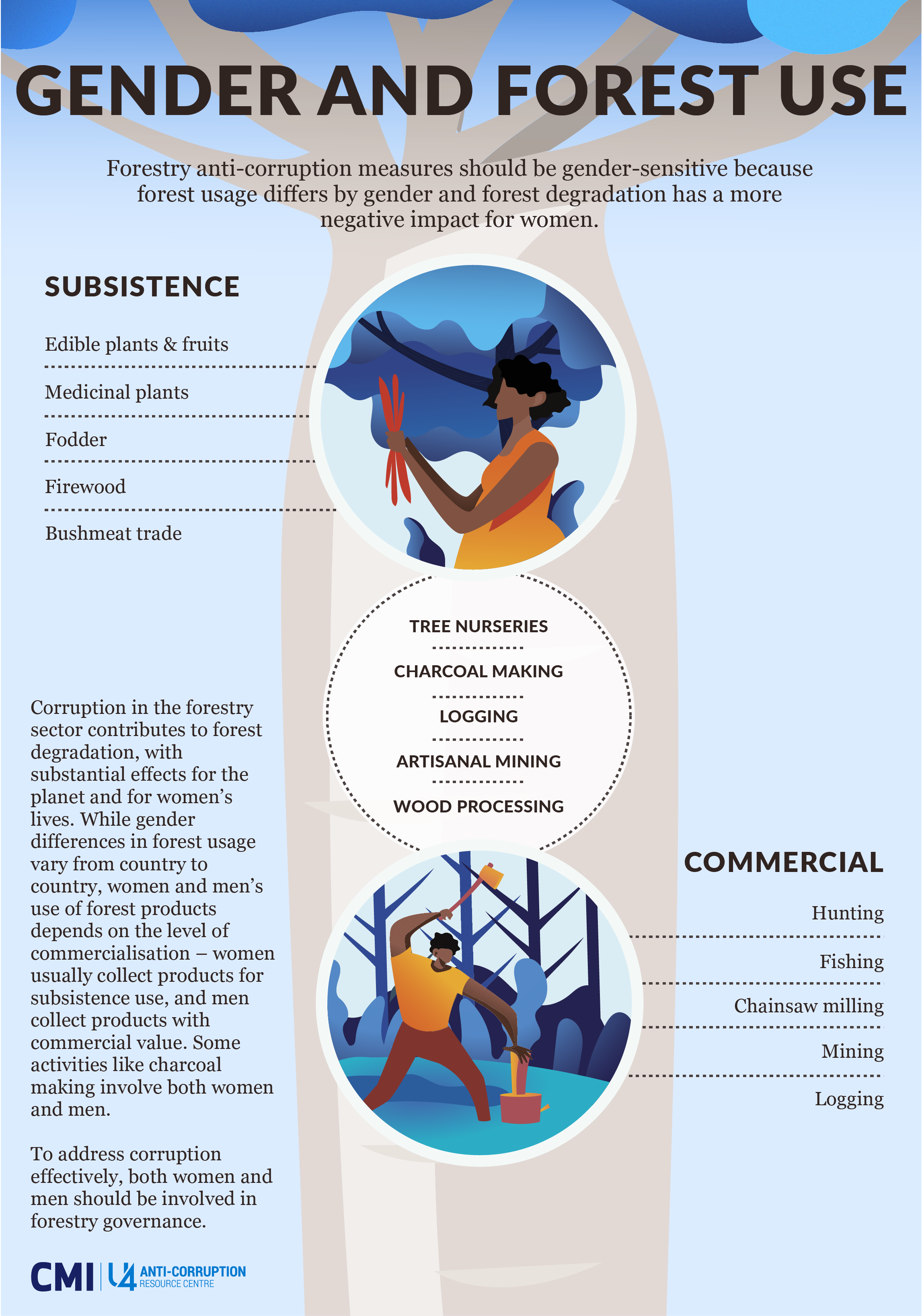

Research shows that gender influences how men and women use forest resources. Men and women are engaged at different stages of production for both timber and non-timber forest products, although this involvement varies from country to country and from one community to another. Studies on the gender differences in forestry activities are limited, so it is not possible to provide a comprehensive picture or cross-country analysis on the issue. Nonetheless, a review of the available data by Sunderland et al. revealed that variations by gender as well as by region are observable in forest product use in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.fc5a2e5addb1

In Africa, while hunting and fishing are male domains, women and girls are involved in collecting edible forest plants, medicinal plants, fodder for animals, and fruits. The plants women collect enable them to supplement the family diet and to earn extra income for their households. In addition, women’s gathering role means they have highly specialised knowledge of the forest, the trees, biological diversity, and conservation practices.ac9e3284932c Women also collect firewood for fuel, a time-consuming activity that often leaves them with little time for school, work, or other productive activities. In Zambia, women are involved in charcoal production from trees, and in the Congo Basin they take part in artisanal mining in forest areas.a4afca1c6f7a Women in Ghana are also involved in chainsaw milling and processing timber, although they are much less visible than men working in similar roles.a69e96944406 In Latin America, however, men play a bigger role than women in the collection of unprocessed forest products such as firewood. In Asia, men’s and women’s contribution to products is roughly equal. Sunderland et al. hypothesise that gender differences in use of non-timber forest products depend on the level of commercialisation, with women dominating in Africa, where collection is mainly for subsistence use, and men dominating in Asia, where forest products such as brazil nuts have high commercial value.7c73b95ac069

Figure 1: Gender and forest use

However, gendered forest use can be fluid and changes depending on the value of the forest products. For instance, in Sierra Leone, a wood collection programme that was supposed to benefit women – because gathering firewood was a female role – was eventually taken over by men because of the new cash benefits it offered.50e7a5419dc8 In addition, gender roles for different aspects of labour and usage may also differ with age, so that, for instance, younger men might work with middle-aged women in tree planting and maintenance.19249bcef556 Gender interests are not monolithic, because gender intersects not only with age but also with ethnicity, religion, wealth, and education level to produce different outcomes for men and women.a50ddd8a0f3b

Gender, participation, and community forest management

Decision-making in the sector shows that community forest management is dominated by men, not only because most forestry officers are male, but also because of the limited participation of women in forest user committees. A cross-country analysis and household survey of ten countries revealed that women’s exclusion from decision-making is due to social, logistical, and legal barriers as well as male bias among those promoting community forestry initiatives. Women are more likely to participate in forest decision-making when the head of the household has a higher education level, when participation demands less time of women, when participation is free and does not depend on payment of a fee, when women have access to income so that there is less income inequality between genders, and when there is a history of prior participation by women.c95c3694df35

Research has established that participation is a complex process. Participation may be nominal and based on mere physical presence, or it may be a more effective form of participation that is interactive and empowering – one that involves taking initiative and exercising influence. Gaventa shows that spaces for participation are not neutral but are imbued with power, and in this way can be closed, opened by invitation, or created. Power relations dictate what is possible within participatory processes and ‘who may enter, with which identities, discourses and interests.’a5d9c6455503 Power in these spaces can be hidden, visible, or invisible, with implications for the transformative potential of such spaces.383ee065c672

Therefore, it is not enough simply to mandate women’s presence is in decision-making processes; the key is to understand the power dynamics that shape their participation. This is because interventions to increase women’s participation in community projects and decision-making can have unintended consequences for forest conservation and for gender relations in the community. For instance, heavy time costs for women in a reforestation project in Nigeria made the project unpopular and contributed to its eventual demise.0c2635f30c3a In Cameroon, Ghana, and the DRC, when women’s income increased as a result of new projects, men reduced their contribution to household expenditure.a3d9f0a5f97d In Gambia, on the other hand, women with new sources of income ‘bought’ freedom from unhappy marriages. These examples show the importance of conducting gender analysis to map the possible outcomes projects may have on power relations in the community.

To participate effectively in the forestry sector, women need the experience, skills, and confidence to engage in the public sphere.ec0e82943b8b Agarwal’s work proposes that substantive representation can be adduced from the extent to which decisions, processes, and regulations take into account the differing gender roles of men and women, and that a critical mass of women, sufficient to have meaningful influence, is attained when women make up at least 33% of forest committees.74e50764e402 However, participation may present an additional burden for women whose schedules are already overstretched with household duties.2edf6548b0b2 Therefore, conducting gender and power analysis for each community is essential before effective participation models can be put in place.

Gender and forest conservation

There is evidence that increasing women’s participation in community forestry institutions improves forest governance and the sustainability of resources. In one study, communities with more women on their forest committees showed better forest condition, and those with all-women committees showed better forest regeneration and canopy growth.2ee64503100f A 2016 multinational study found improvements in local governance and conservation of natural resources when women participated in management of the resources.11e0f4836667 A recent study from Nepal showed that an increase in female decision-making power in forest groups led to a reduction in firewood collection, and higher female participation in executive committees favoured decisions that prioritised sustainable extraction of firewood.3dcf0705b0b0

The limited participation of women in forestry management bodies does not mean they have no power or agency. Women have long been involved in forest conservation and tree planting programmes. Wangari Maathai’s women-led Green Belt Movement in Kenya won international recognition, and she was awarded a Nobel Prize for her efforts to engage communities, especially women, in planting trees.c755de0ebc05 Women have also played a key role in the environmental movement in Sweden,59ba0683e51e India,962ea34e0b94 Indonesia,1ab0c5e07060 the United States,0ab617d9325f and several other countries.

In addition, women have been known to sabotage conservation programmes that excluded or did not benefit them.ecf1d830c1ee It may therefore not be sufficient to simply mainstream gender; rather, steps should be taken to ensure that programmes have specific empowerment objectives for both men and women in order to avoid an outcome of conflict or confrontation between genders because one gender feels disempowered.0d05369fce2c

Gender and climate justice

Climate change is probably the most crucial issue facing the world, and ongoing policy processes recognise that climate change will impact men and women in different ways, potentially exacerbating gender inequality and increasing women’s vulnerabilities. Rural women whose livelihoods depend on forests are particularly under threat, as forest cover continues to be consumed by wildfires that start and spread in hot, arid conditions. Changing weather patterns also affect water availability, agriculture, and food production. Evidence shows that extreme weather phenomena such as cyclones and hurricanes, which have become more frequent because of climate change, affect women more than men due to pre-existing gender income gaps and other vulnerabilities arising from women’s lower status in society.a7d1b496d1fe

Community-based adaptation (CBA) mobilises communities from the bottom up to prepare for and respond to climate change. Tailored to local context, CBA seeks to increase resilience to climate risks by strengthening social networks and cementing links with supporting institutions. It incorporates local knowledge and local decision-making processes in regard to perceptions of climate change and risk management strategies, such as adopting more drought-resistant crop varieties. Local social networks provide a form of insurance following shocks. The success and impact of CBA, however, depends in part on which community members participate in the development and adoption of CBA strategies, such as planting trees or modifying agricultural practices. Here, gender is regarded as an important variable, as climate change affects men and women differently. Risk is not equally shared between men and women at the household or community level due to differentiated gender roles for child care, water and fuel collection, and food production, processing, storage, and marketing. Indeed, men and women may assess climate risk differently depending on the gender roles in a given community. Another issue is that participation in CBA activities is often predicated on education level, income, and wealth, areas where women tend to fare worse because of persistent gender inequality.4de4b2c4c46d Both men and women should be included in CBA activities in order to address the needs of both genders.

The REDD+ climate change adaptation initiative recognises community participation as essential to the success of the scheme. However, one of its weaknesses has been the tendency to see communities as homogenous and to not take gender differences into account. This is pertinent because REDD+, by discouraging forest use, may negatively affect the livelihoods of communities that depend on forests for food and income. A global comparative study of REDD+ in six countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America showed significant variation in the extent to which women participate, influence, and are represented in village and household decision-making. Although women were members of decision-making bodies at village level, the study found that they were less knowledgeable about REDD+ than the men who took part in the study.ea9614455fa8 Other research has shown that women are not sufficiently represented in REDD+ processes, and that even when they are represented, participatory mechanisms fail to take into account the underlying power issues that limit women’s voices in the public sphere, rendering their participation merely tokenistic. For instance, an analysis of REDD+ documents in Indonesia found that only 88 of 383 mentioned the word ‘gender,’ and of those 88, very few included gender mainstreaming principles in a substantial way.15f8c6ed42ce This not only has implications for women’s ability to benefit from REDD+, but could also compromise conservation efforts.9330f2076302

To sum up, the research on gender and forestry shows that gender is an important consideration in forest management and conservation. The differences in how men and women use forests vary from country to country, but the overall pattern appears to be that women use forests mostly for subsistence purposes and men for commercial ones. This distinction between subsistence and commercial use may in turn affect the configuration of gender roles when economic circumstances change and a product that previously had no commercial value suddenly becomes valuable. Another important issue is the centrality of effective participation mechanisms in forest management, especially as women and men use forests differently and might have different priorities and interests. Therefore, it is not enough to just include women; it is also important to ensure that their voices are heard.

Gender dynamics in forestry corruption

Men’s and women’s involvement in corrupt activity

Given the dearth of studies in this area, it difficult to ascertain to what extent women, as opposed to men, are involved in corrupt activities in the forestry sector or even the extent to which they are victimised by forest-related corruption. Both men and women living in communities near forests can be involved in illegal charcoal production, illegal cutting of rare wood species, and illegal extraction of non-timber forest products.96346ad05a5b Illegal logging and wildlife crime are in most cases carried out by men due to their dominance in logging and hunting generally. Research from Liberia revealed that hunting, logging, and mining in the forest were exclusively male activities, while women were involved in farming, gathering firewood for fuel, obtaining building materials, and foraging for herbs.29bf479fff31 However, in some countries women are involved in charcoal burning, often an illegal activity.4a1e5c82a8b6

In some cases conservation efforts give rise to opportunities for corrupt activity. Research shows that forest protection efforts can allow rangers and other public officials to demand bribes in cash or in kind from community members who try to continue using forests as they did before those forests became protected areas.7534892d8998 Women are frequently the victims of extortion by forest guards and rangers. A study in Odisha State, India, focused on a community that had been relocated from a protected forest but continued to travel back to that forest to collect non-timber forest products. The women reported that they were often made to share their gatherings with the forest guards they met along the way. Research elsewhere in India, in Rajasthan State and Kandhamal District, revealed similar problems: women no longer had access to the forests that previously sustained them, and this severely affected their livelihoods.881faca2d9da Similarly, efforts to control wildlife crime and limit bushmeat trade in the Democratic Republic of Congo through criminalisation has created opportunities for bribe demands and extortion of women bushmeat traders.5389af9a0589

The gendered impact of corruption in the forestry sector

It is possible to infer that women suffer the effects of corruption in the forestry sector more than men. The effect is not linear but indirect, and can be deduced from the differential impact of forest degradation on women and men. As mentioned above, there is substantial evidence of a link between corruption and deforestation; hence there is an indirect link between corruption and the effects of deforestation.

Illegal logging and deforestation have direct detrimental effects on forest-dependent people’s livelihoods by decreasing their access to both timber and non-timber forest products. When women’s access to forests is constrained, they have to travel longer distances to obtain the resources they need. Firewood collection is one of the most time-consuming chores for rural women; the farther women must walk to find wood, the more time and energy they must spend, leaving them less time to be involved in economic activity and civic life.008bde6b04f4 Carrying heavy loads of fuelwood or other forest products over long distances also has detrimental effects on women’s health and well-being.e7548df6e7ae

Deforestation leads to soil erosion, with negative implications for soil quality and therefore food security. Rural women in many parts of the world bear the primary responsibility for growing, harvesting, cooking, and serving food. Accordingly, the increasing degradation of the soil due to deforestation affects rural women who depend on subsistence agriculture the most. Soil erosion also leads to contamination of clean water sources, which become muddy and filled with silt. Again, women have the responsibility for fetching water, so silted and contaminated water sources increase their burden of household chores and exacerbate the gender-unequal division of labour.5df82a07ac88

Illegal logging and the resulting deforestation are drivers of global warming and climate change, whose effects are already being felt and will increasingly be felt more keenly by poor women living in areas vulnerable to climate-related disasters.b451b4c0e316

The loss of revenue and tax income from illegally harvested wood worldwide is estimated to be at least US$10 billion per year.6228074add6a Illegally traded timber deprives governments of income that could be used to provide social services such as health and education, which have been shown to play a key role in human development, especially in improving the lives of women and girls.e8aade93121b

Lastly, the competition for forest resources is one of the drivers of violent conflict in areas such as the Democratic Republic of Congo. Such conflict has had a disproportionate effect on women, who have suffered unspeakable sexual and gender-based horrors in the course of this violence. Indeed, loggers have been implicated in human rights abuses committed in the DRC.77de3664a2f1 Illegal logging operations in other parts of the world such as the Amazon often involve murder, violence, threats, and atrocities against indigenous forest-living peoples.d92207545124

Towards an integrated approach to gender, forestry, and corruption: Suggestions for research, policy, and practice

The women’s movement has made considerable progress in integrating gender equality and women’s concerns into international and national plans and processes, including those relating to the environment. As long ago as 1985, the United Nations, in the Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women, recognised that changes in the natural environment would be critical for women, given their role as ‘intermediaries between the natural environment and society with respect to agro-ecosystems, as well as the provision of safe water and fuel supplies and the closely associated question of sanitation.’8bf28ca0211e It would be another few years before the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, known as the Rio Earth Summit, placed environmental concerns squarely on the international agenda, and it is only during the past decade that climate change has risen to the top of the global agenda as the most urgent problem facing humanity. On the other hand, curbing corruption only became a major issue on the development agenda in the late 1980s and early 1990s, culminating in adoption of the Anti-Bribery Convention of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1997 and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) in 2003.

A more integrated approach to gender, forestry, and corruption is necessary to effectively address climate change. Given the dearth of studies on how the three are interrelated, this paper offers suggestions for further research as well as for strengthening policy-making and activism in the forestry sector through a gender-sensitive approach. These suggestions are based, first, on the research findings that there is a strong correlation between gender equality and control of corruption across sectors. Although the connection is not yet well understood, the evidence is enough to suggest that in general, improving gender equality reduces corruption. Second, it is apparent that forestry corruption has dire implications for women due to their heavier burden of domestic duties and the fact that they are more likely to be poor. They are therefore more vulnerable to the detrimental effects of environmental degradation, including deforestation. Third, the involvement of women in forest governance and decision-making continues to be low despite efforts to promote it, and where women are included in forestry committees, their participation is often tokenistic and not meaningful. This has negative implications for forestry conservation, since studies have shown better conservation outcomes in areas where women are meaningfully involved in making decisions. These findings underscore the need for a gender-sensitive approach to forestry governance.

Integrating gender, forestry, and corruption in academic research and analysis through ecofeminism

Ecofeminism is a theoretical framework that addresses the link between gender discrimination and environmental degradation. Pioneered by Shiva and Mies, it posits that male-dominated systems of power have perpetrated both environmental degradation and discrimination against women.50327e3a74cf Ecofeminism is a form of radical feminism that is opposed to simply mainstreaming gender into ‘business as usual’ structures of power and ways of doing things. The ecofeminist movement has attracted some controversy because it promotes what some feminists regard as a stereotypical, essentialist view of women as having closer, perhaps mythical, ties to nature and the environment.ae34e68a9e62

It is, however, regaining prominence as a form of feminist political ecology, especially among activists. Indeed, the progress that has been made so far in integrating gender and women’s concerns in environmental discourse can be credited to the ecofeminist movement.141fd5df3dc7 The Chipko ‘Embrace the Tree’ movement, a nonviolent social and ecological movement that started in the 1970s in Uttar Pradesh, India, is one of the earliest examples of ecofeminism in action. In its first protest, in Mandal village in 1973, women literally embraced trees as a tactic to prevent logging, which was thought to have contributed to severe monsoon flooding in the region a few years previously, in 1970.58257a58a5ea

The Green Belt Movement started by Wangari Maathai is another example of a successful ecofeminist initiative. It has inspired an Africa-wide movement known as the African Eco-Feminist Collective, which promotes radical and African feminist traditions as a basis from which to critique power, challenge multinational capitalism and its destructive effects on the environment, and reimagine a more equitable world.aa043c290c46

Ecofeminism provides a valuable framework within which to consider how to integrate gender into anti-corruption research, policy-making, and activism in the forestry sector. By critiquing existing power structures and modes of governance, eco-feminism reminds us that simply having more women in positions of power might not necessarily reduce corruption unless the structures of power and culture change in a manner that allows power to be exercised in a people-centred, democratic manner. In this sense, it resonates with Gaventa’s ideas about the need to pay attention to power dynamics in participation spaces.e17c1fe89916 Eco-feminism has always interrogated power and can help turn the spotlight to corruption and abuse of power as a patriarchal phenomenon. Feminist researchers can contribute to the continuing debate on gender and corruption by conducting research and interrogating how structures of power that exclude women, youth, persons with disabilities, and ethnic, racial, and sexual minorities perpetuate corruption, deforestation, and other negative development outcomes.

Researchers can help shed light on how men and women are involved at various stages of the supply chains for timber and non-timber forest products, and identify points at which corruption, exploitation, and abuse are prevalent. Ethnographic inquiry into the effects of forest degradation on men and women, and on vulnerable groups such as indigenous communities, would also be helpful. Intersectional research that considers not only gender but also factors such as age, religion, disability status, sexual orientation, ethnic background, and education attainment as variables in forestry participation would enable policy-makers to craft more effective solutions for this sector. Indeed, many development actors, including governments, donors, and NGOs, already embrace a commitment to gender equality and inclusiveness. More needs to be done to implement this commitment in all sector-level initiatives.

Integrating gender into political economy and power and influence analysis in the forestry sector

For some time now, development practitioners have recognised that taking a politically informed approach to development programmes can help improve their effectiveness. This involves analysing sites of power and influence to determine what the programme can feasibly achieve, which interventions to work on, and which actors to involve. In addition, many development programmes try to adopt a ‘gender-aware’ approach, which often involves undertaking gender analysis and mainstreaming gender in the programmes.

A recent enquiry by the Gender and Politics in Practice project at the Developmental Leadership Program, however, found that gender is seldom integrated into politically aware programming and that ‘the two approaches have tended to operate on parallel tracks – to the detriment of both.’49c68a13a45b The authors note that since both approaches aim to analyse and reform unequal power dynamics to achieve change, bringing them together would promote more transformative development programmes.

Gender can be integrated into political and governance analyses of the forestry sector by considering the following:

- The role of gender in society and how it shapes institutions, attitudes, and economic factors such as women’s land tenure and property/business ownership along the timber supply chain.

- How gender dynamics play out in the sector, for instance, what is considered women’s work and men’s work, and the impact of such thinking on national development.

- The extent to which women hold positions of power and influence, for instance, how many women sit in parliament and how many are business or civil society leaders in forestry and affiliated sectors.

- The challenges faced by women and men in accessing positions of power, and whether women in power have any actual influence on forestry policy.

- The representation and influence of women’s groups, whether lobbying groups exist for women's rights, and how much success they have in advancing their causes.

- How the political and economic situation affects men and women differently at all levels, from national to household.8517e9421913

Promoting gender-aware and inclusive approaches to forestry anti-corruption initiatives

Forestry anti-corruption programmes should adopt a more gender-aware approach. At the international level, the Environment and Gender Index (EGI), developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, is a new tool to monitor progress toward gender equality and women’s empowerment in the context of global environmental agreements. Piloted in 2013, it provides a practical entry point to comprehensively strengthen transparency, accountability, and gender-mainstreaming approaches. At the moment, the EGI is based on the Rio Conventions on biodiversity, climate change, and desertification,dd1f5ba99190 which are cross-referenced against the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). The EGI provides information and quantitative data on governments’ performance in translating the gender and environment mandates in the three Rio Conventions and CEDAW into national policy and planning. The index has two aspects: gender-responsive environmental policy and women’s participation in decision-making. Indicators include the inclusion of gender in national plans or reports linked to the Rio Conventions, the inclusion of environment in gender-related plans, and participation of women in environmental decision-making.7d9ed9a358c0

One of the EGI’s stated purposes is to promote a culture of greater transparency and accountability; however, this appears to focus mainly on the sphere of gender equality and women’s rights and not on national or environmental governance. The indicators on governance assess the effectiveness of a country’s fundamental institutional capacities and the ability of its citizens to participate freely in the political process. They measure this by considering the status of civil liberties, political stability, and property rights. The EGI also considers the importance of gender in country-reported activities on the Rio Conventions and looks at whether CEDAW reports contain information on environmental sustainability. In future, the EGI could expand the governance indicators it incorporates to include some that concern anti-corruption, transparency and accountability (ACTA) in governance. This is crucial because corruption is one of the biggest threats to sustainable environmental and natural resource governance.

Other international-level forestry governance initiatives such as REDD+ and FLEGT have recognised the importance of gender and inclusion.ce08946d39c0 FLEGT is promoting research to examine the involvement of women in the timber supply chain so that their needs and concerns can be incorporated into the FLEGT process.6cf702592bde

At national level, community forestry mechanisms should ensure gender balance and should be equipped, trained, and authorised to enhance transparency and accountability through social accountability mechanisms such as participatory budgeting, participatory audits, community scorecards, and other feedback mechanisms. As mentioned previously, participation should be not just tokenistic, but meaningful. Tokenistic participation can occur in several ways, for instance, when women are brought into a process late, when they are not given enough information about the process, and when they are relegated to isolated observer or ad hoc advisory roles.f0e82cbc7d51 Figure 2 presents a framework for meaningful participation suggested by the women’s peace-building and conflict resolution movement.

Participation in budgeting and planning is seen as a way to improve transparency and accountability and reduce corruption. Participatory budgeting can be made even more gender-responsive by introducing gender-responsive budgeting (GRB). Civil society organisations such as Oxfam have been at the forefront of promoting GRB, which involves analysing government budgets for their gendered effect on women and men and the norms and roles attributed to them. It also involves making changes to budgets to guarantee that gender equality commitments are realised. Gender-responsive budgeting looks at how revenues are raised (through taxes, fees, fines, etc.) and how they are lost (through tax havens, tax dodging, and other illicit financial flows); how money is spent (for example, on public services or infrastructure); and whether actual spending is in line with agreed budgets. It also considers whether spending is sufficient and targeted to meet the practical and strategic needs of men, women, girls, and boys, and how decisions on raising and spending money affect gender roles, such as unpaid care work and subsistence work and their distribution between genders.b551dfa4369a GRB in the forestry sector can therefore be an important tool for integrating gender into forest sector anti-corruption programmes.

Figure 2: Components of meaningful participation

Source: Adapted from UN Women (2018).

Whistleblowing and complaints mechanisms, including those for reporting sexual harassment and abuse, should cater to both men and women. In some settings women have lower literacy levels and/or lack access to technology-based mechanisms for reporting wrongdoing. They may sometimes prefer reporting face-to-face, rather than making a phone call or dropping a note in a box, and these preferences and limitations should be taken into account.

Access to information is crucial for both gender equality and accountability. Open forestry data would enhance cooperation between governments and civil society in finding solutions to the problems in the sector. Data could include satellite images of forest cover, information on licenses and concessions, as well as information on budgets, resources, and staffing. Communities and civil society organisations need information to mobilise against practices such as illegal logging that threaten their livelihoods, so open data should be smartphone-friendly and easily accessible. In any case, information should be in a format that can easily be accessed by both genders, taking into consideration literacy and access to technology.

Gender-aware approaches in the forestry sector would also provide the opportunity for an in-depth look at gender dynamics along timber supply chains. This may include uncovering the gendered aspects of corruption, from sextortion to modern slavery, in the supply chain and creating appropriate responses to such practices.d0523793d44d

Table 2 illustrates a framework for forestry anti-corruption initiatives based on the four pillars of transparency, accountability, participation, and anti-corruption mechanisms and actions, with several specific approaches suggested for each pillar.

Table 2: Suggested gender-sensitive anti-corruption framework for the forestry sector

|

Transparency |

Accountability |

Participation |

Anti-corruption |

|

Promote open forestry data and ensure that the information is accessible to both men and women (considering information technology access, literacy rate) Publish proposals and plans in accessible formats Develop advocacy strategies and engage with the media Publish research findings in an accessible manner Promote gender-responsive participatory budgeting by combining gender budgeting and commonly used PB approaches |

Clarify lines of responsibility and reporting Build sector capacity to deliver on Sustainable Development Goals 6 (gender equality) and 16 (peace, justice, strong institutions) Build sector capacity to report on international law obligations, including the environmental concerns in CEDAW and gender concerns in UNCAC Ensure transparency in financial management and procurement Provide gender-sensitive whistleblowing and complaints mechanisms, including on sexual harassment and abuse Promote impartiality and procedural fairness in administrative decision-making |

Make participation of both men and women in sector mechanisms a requirement under law Balance stakeholder interests in policy-making and legislation, taking into account the needs and interests of both men and women Use participatory mechanisms that include representatives of vulnerable groups, are gender-balanced, and have safeguards against elite capture Equip members to understand the issues at stake so they can raise their concerns Make sure that complaints mechanisms have feedback loops Train and equip user groups and community monitoring mechanisms to be inclusive and effective Create participatory mechanisms that can address gender disparities and corruption problems |

Strengthen regulatory mechanisms and justice systems and make them gender-sensitive by including a critical mass of women who are able to influence decisions and processes Institute merit-based recruitment in the forestry sector and ensure that public servants are trained on gender, forestry, and corruption Strengthen links between forestry mechanisms, anti-corruption bodies, and gender-mainstreaming bodies Publish codes of conduct for foresters and committee members, prohibiting conflicts of interest and other forms of corrupt behaviour |

Source: Adapted from the Water Integrity Network’s Integrity Wall.

Promoting women’s involvement in the anti-corruption movement in the forestry sector

As previously mentioned, women have been active in the environmental movement for decades, and anti-corruption social movements led by women’s groups have emerged. A good example is Saya Perempuan Anti-Korupsi (SPAK) in Indonesia, which was launched in 2014 (the name translates roughly as ‘I, Woman Against Corruption’). With more than 1,025 SPAK agents active in each of Indonesia’s 34 provinces, SPAK is one of the biggest female-led anti-corruption social movements in existence today. The movement targets women from a range of employment and professional backgrounds to become members. Women undergo a three-day training to enable them to understand the different forms of corruption; they commit to be corruption-free in their own lives and to do their best to curb corruption in families, communities, and the larger society.e0133fd35951 Such movements can and should be encouraged to tackle forestry-related corruption as part of their objectives.

Initiatives to promote women as anti-corruption champions should, however, be carefully designed to avoid reinforcing gender stereotypes about females’ higher integrity and lower likelihood of cheating. Thus, any projects should be preceded by a gender analysis exercise that considers gender relations and gender stereotypes, and plans should be put in place to mitigate any unintended harmful consequences.

Corruption risk management for women’s empowerment and gender equality programmes in the forestry sector

Much of the discussion so far has focused on how to integrate gender into forestry anti-corruption initiatives and programmes. As a corollary, it is also important for women’s activities in the forestry sector to consider corruption as a threat to gender equality and women’s empowerment. As discussed above, corruption in forestry has a disproportionate impact on women. Therefore, corruption risks should be taken into consideration when designing and implementing initiatives aimed at empowering women and promoting gender equality in the forestry sector. This can be done by incorporating corruption risk management principles into gender analysis, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Including corruption in gender analysis

| Gender analysis considerations | Potential corruption aspects |

| Gender role stereotypes | How do stereotypes and norms around masculinities and femininities influence corrupt behaviour? |

| Men’s and women’s conditions, needs, and constraints | How does the abuse of power (corruption) affect the lives of men and women and possibly worsen their situations? |

| Men’s and women’s participation rates and decision-making power | How do corruption, patronage, and clientelism as patriarchal phenomena affect men’s and women’s abilities to participate in public life and decision-making? |

| Men’s and women’s access to and control of resources | How does corruption limit men’s and women’s access to and control over productive resources? |

| Intersectionality: the influence of race, ethnicity, age, class, income, educational attainment, disability status, etc., on all the factors above | How does corruption affect marginalised and vulnerable groups? |

Recommendations

Donors and multilateral bodies

Donors are well placed to fund initiatives that promote gender-sensitive approaches to anti-corruption efforts in the forestry sector. Donors can:

- Support efforts by international and multilateral bodies to integrate gender considerations and anti-corruption actions in international forestry sector initiatives.

- Support efforts by governments to mainstream both gender and anti-corruption efforts in the forestry sector.

- Support civil society organisations working in gender and forestry, helping them adopt an integrated approach to gender and corruption.

- Support academic research into gendered forms of corruption and the gendered impact of corruption in the forestry sector.

Governments

Governments have the primary responsibility for adopting gender-sensitive approaches to forestry anti-corruption measures. Towards this end, they can:

- Integrate both gender considerations and anti-corruption initiatives in forestry sector strategies and plans.

- Mandate women’s participation in forestry user committees and ensure meaningful participation of all groups.

- Enable and encourage women to join forestry-related professions and activities.

- Ensure the compilation of gender-disaggregated data regarding forest usage, forestry supply chains, and forest governance mechanisms.

Activists, NGOs, and civil society organisations

As mentioned above, combating corruption is a feminist cause because corruption has a disproportionate impact on women. Women’s rights NGOs and activists should:

- Consider how corruption hinders their project goals and include reducing corruption as part of their project goals for improving gender equality.

- Adopt or contribute to existing anti-corruption methods such as participatory budgeting, and make them more gender-responsive.

- Act as whistleblowers on illegal logging and other forms of forestry corruption.

- Collect gender-disaggregated data on forestry usage and forestry corruption and their effects on communities as part of their monitoring activities.

Researchers and scholars

More research is needed on the links between gender, forestry, and corruption. Potential research questions include:

- How are men and women involved in corrupt and illegal activities along the forestry supply chain in the informal sector, the private sector, and the public sector?

- What are the differential effects of forestry corruption on men and women?

- Is there a causal relationship between gender in environmental decision-making and control of corruption (as shown by regression analysis)?

- Under what conditions does increasing the number of women involved in community forest management and decision-making lead to reductions in illegal logging?

- Dollar, Fisman, and Gatti (2001); Swamy et al. (2001).

- The gender equality ratings are based on the World Bank Group’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) database. The Worldwide Governance Indicators report on six dimensions of governance, including control of corruption.

- Boehm (2015).

- Esarey and Chirillo (2013).

- Goetz (2007).

- Esarey and Schwindt-Bayer (2017).

- See, for example, Sung (2003, 2012).

- See, for example, Bauhr, Charron, and Wängnerud (2019).

- Watson and Moreland (2014).

- Bjarnegard (2013). See also Sundstroom and Wangnerud (2014).

- Bjarnegard (2013). See also Merkle (2018), especially chaps. 3 and 4.

- Boehm (2015). See also Alhassan-Alolo (2007) and Alatas et al. (2009).

- Sierra and Boehm (2015). See also Hallerod et al. (2013).

- Merkle (2018), chap. 2.

- IAWJ (2012), p. 13.

- Sextortion is also used to refer to a crime in which threats to expose a sexual image are made in order to coerce the victim to do something, or for other reasons such as revenge or humiliation. In this explanatory video from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, the FBI special agent defines sextortion as ‘a serious crime that occurs when someone threatens to distribute your private and sensitive material if you don’t provide them images of a sexual nature, sexual favours, or money.’ This differs from the definition promoted by the IAWJ, so we urgently need some conceptual clarification in order to draft appropriate policies.

- Transparency International (2019).

- King and Mason (2001).

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Article 7. See also the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 25.

- UNODC (2012).

- Colfer, Basnett, and Elias (2016).

- Koyuncu and Yilmaz (2009).

- See, for example, Meyer, van Kooten, and Wang (2003), Wright et al. (2007), and most recently, Sundstrom (2016).

- Commonly used definition by Transparency International.

- Bonan (2008).

- Kleinschmit et al. (2016), chap. 8, p. 133.

- Blaser and Zabel (2016).

- Interpol (2016).

- Kishor and Damania (2007).

- KPK (2010).

- UNEP and Interpol (2012).

- UNEP and Interpol (2012).

- KPK (2013).

- See, for example, Pendergast, Clarke, and Van Kooten (2011), who argue that a forest resource curse is more likely where there are pristine/virgin forests as opposed to plantation ones.

- Kishor and Damania (2007).

- Standing (2012).

- Assembe-Mvondo (2015).

- Dupuy (2014).

- Kenya Ministry of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (2013).

- Lucas (2016).

- Bhalla (2016).

- European Commission (2019).

- EU FLEGT Facility (2019a).

- Dauvergne and Lister (2011).

- Fraser (2014).

- Fraser (2014).

- Hoskins (2016).

- FAO (2019).

- FC and IUCN (n.d.). See also CIFOR (2016) and Marin and Kuriakose (2017).

- CIFOR (2013).

- Sunderland et al. (2014).

- FAO (n.d.), quoting Sunderland et al. (2104).

- Ihalainen et al. (2018). See also Ingram et al. (2011) and Funoh (2014).

- Yirrah (2018).

- Sunderland et al. (2104).

- Leach (1991).

- Leach (1991).

- Mwangi and Mai (2011).

- Coleman and Mwangi (2012).

- Gaventa (2006).

- Gaventa and Martorano (2016).

- Leach (1991).

- Abbot et al. (2001), Dei (1994), and Schoepf and Schoepf (1988).

- Agarwal (2010b).

- Agarwal (2010a).

- Bolanos and Schmink (2005).

- Agarwal (2009).

- Leisher et al. (2016).

- Leone (2019).

- Maathai (2003).

- Peterson and Merchant (1986).

- Jain (1984).

- Arumingtyas (2017).

- Kennedy (2016).

- Schroeder (1999), quoted in Harris-Fry and Grijalva-Eternod (2016).

- Harris-Fry and Grijalva-Eternod (2016).

- Terry (2009).

- Bryan and Behrman (2013).

- Larson et al. (2016). The countries analysed were Brazil, Cameroun, Indonesia, Peru, Tanzania, and Vietnam.

- Wornell, Tickamyer, and Kusujiartu (2015).

- Khadka et al. (2014).

- Blaser and Zabel (2016).

- African Women’s Network for Community Management of Forests (2014).

- Ihalainen et al. (2018).

- Blaser and Zabel (2016).

- Bhalla (2016).

- LaCerva (2016).

- Carr and Hartl (2010).

- Wan, Colfer, and Powell (2011).

- Samandari (2017).

- Blaser and Zabel (2016). See also Terry (2009) and Denton (2002).

- Interpol (2016).

- King and Mason (2001).

- Global Witness (2015).

- UNEP and Interpol (2012).

- United Nations (1985).

- Mies and Shiva (1993).

- See, for example, Moore (2004, 2008).

- Buckingham (2004).

- Jain (1984).

- Merino (2017).

- Gaventa (2006); Gaventa and Martorano (2016).

- Derbyshire et al. (2018).

- Browne (2014a, 2014b); Griffin (2007). See also Peterson (2005) and Pettit (2013).

- The United Nations Convention on Biodiversity, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification all derive from the 1992 Earth Summit that took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- IUCN (n.d.).

- EU FLEGT Facility (2019b).

- Yirrah (2018).

- UN Women (2018).

- Oxfam International (2018).

- Hussain (2019).

- UNODC (2018).