Digital feedback mechanisms for development

Digital platforms are often promoted as tools for improving accountability and service delivery in education, with the promise of amplifying citizen voices, monitoring frontline services, and fostering more responsive governance. Their effectiveness, however, depends on political will, institutional capacity, and citizen trust, factors that are frequently weak or absent in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Olavula, an SMS-based feedback platform launched in two northern districts in Mozambique in 2013 and now covering over 30 districts, provides a compelling case study of both the potential and the limitations of digital accountability tools. Designed to collect and respond to citizen feedback on education services, Olavula has operated in a region marked by conflict, poverty, and weak service-delivery systems. Its experience offers valuable insights into how digital civic engagement mechanisms function in practice under resource-constrained and politically challenging conditions.

This study does not evaluate Olavula as a project; rather, it uses the platform as a lens to examine broader questions about the uptake, effectiveness, and institutional integration of digital feedback systems. In doing so, it contributes to ongoing debates on whether such tools can narrow the gap between citizens and the state, strengthen service delivery, and directly or indirectly enhance integrity and transparency in public services. While Olavula was not explicitly designed as an anti-corruption intervention, it illustrates how grievance redress and feedback mechanisms can influence transparency, accountability and governance outcomes.

The paper begins by outlining the study’s aims and methodology and situating the analysis within broader debates on digital platforms and citizen engagement. We examine the context in which Olavula was developed, including the governance, conflict, and service delivery challenges that shaped the initiative, alongside a description of the platform’s design, objectives, and implementation. Next, the findings on uptake, usage, and institutional responsiveness are drawn from interviews, usage data, and programme documentation, all of which informed our analysis of the platform’s impact. This is followed by a critical reflection on the challenges encountered, the broader implications of Olavula’s experience for social accountability and anti-corruption efforts. The paper concludes by offering recommendations for development partners, implementers, and policymakers considering the use of digital feedback mechanisms in fragile settings.

Study aims and methods

The study focused on the lessons drawn from the design, implementation, and experience of Olavula, particularly on citizen feedback and its role in improving public service delivery. Specifically, the study sought to:

- Investigate how Olavula was conceptualised and implemented within a fragile governance context.

- Assess patterns of uptake and usage among citizens and public officials, identifying enablers and barriers to engagement.

- Explore the platform’s institutional integration and its influence or lack thereof on service delivery responsiveness.

- Reflect on the broader relevance of digital feedback mechanisms for accountability and anti-corruption agendas, especially in contexts of conflict, weak state capacity, and low institutional trust.

The research combined several sources of evidence. A selective literature review was conducted on the role of digital accountability platforms in public service delivery, with a particular emphasis on the education sector. This was complemented by an exploratory review of programme evaluations of similar initiatives, focusing on challenges of implementation, handling of corruption-related complaints, and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Primary data was gathered through remote interviews with key actors involved in Olavula in Mozambique, conducted between late 2019 and early 2020.6a986aef48a6 To address the time lag between initial data collection and the completion of this paper, the findings were revisited and cross-checked with respondents in early 2025. This allowed the study to validate earlier observations and incorporate more recent reflections. Triangulation across interviews, reports, and secondary sources ensured that the analysis reflects both contemporaneous experiences and subsequent developments.

The key actors/institutions interviewed were: Centro de Aprendizagem e Capacitação da Sociedade Civil (CESC);bc96007d3b87 Diakonia (development organisation); CAICC (Centro de Apoio a Informação e Comunicação Comunitária;670f4c103374 Fórum Nacional das Rádios Comunitárias (FORCOM);9c36427a0649 the Mozambican Ministry of Education and Culture; and Centro de Integridade Pública.855eed62c37d We also interviewed local implementers, such as school directors, change agents, facilitators, and lecturers. In development terms, the ‘beneficiaries’ of the Olavula project are all the members of the community who are able to use the platform to make complaints about education or health services. However, as complaints are made anonymously, direct access to complainants was difficult. For this reason, we interviewed community representatives as proxies for these beneficiaries, and as change agents in their own right.

Enabling factors for effective service delivery digital portals

The literature suggests that digital platforms are often promoted as accountability tools because mobile phones are perceived as nearly universal, allowing citizens to report service delivery problems through calls or SMS.b081da6c0b81 In practice, this assumption is not always borne out. Many citizens are unaware that these services exist at all, and of those that are aware, many are unsure how to use them or simply choose not to engage for a variety of reasons. Moreover, when reports are not acted upon or resolved satisfactorily, motivation to use the platforms declines.

Three lessons therefore stand out: first, citizens must be willing and able to engage; second, the type and quality of data collected must be actionable; and third, follow-up action is essential to improve accountability and to sustain citizen trust and participation.

Citizen engagement

Citizen engagement is the foundation of any successful digital accountability platform. One of the most prominent examples is UNICEF’s U-Report, a free SMS-based system that allows members to respond to weekly polls, with results aggregated in real time. U-Report launched in Uganda in 2011 and has since expanded to more than 90 countries, including Mozambique, attracting millions of subscribers.c7b09c2f0f8a As with many repeated and online surveys, U-Report struggles to sustain high levels of participation among registered users. Case-study evidence from Uganda, for example, points to low response rates to polls as a challengedf29fc017f65 This is consistent with broader literature on survey methods, which documents declining response and attrition over time in panel surveys and online surveys.b019b391aaf2

The uSpeak programme, a spin-off from U-Report designed to connect Ugandan citizens with members of parliament, further illustrates this challenge. While small-scale experiments showed that SMS-based dialogue could engage marginalised populations and increase politicians’ awareness of their constituents’ issues, the effects disappeared when the programme was scaled up nationally.9105e29ec750 Marginalised groups were least likely to engage, partly because awareness campaigns relied heavily on radio, a channel less accessible to poorer households. These findings underscore the need for platforms to complement digital tools with inclusive outreach strategies that reach women, minorities, and people with limited digital access.

More recent studies also show that many citizens prefer in-person complaint channels, partly because of confusion over the growing ‘array of hotlines and digital platforms’ introduced during the Covid-19 pandemic. The studies suggest that blended approaches that combine digital feedback with offline engagement appear to work best.6da4bd09f257

Data quality

Platforms must collect information that is specific and actionable. The U-Bridge initiative – another Ugandan spin-off from U-Report – sought to improve local service delivery by connecting citizens and officials via SMS. However, many of the reports received were too vague to trigger concrete action. Evaluators recommended citizen training to improve message quality, but overall the programme showed little measurable impact on service delivery outcomes.a7993304cac3 This highlights the need to design platforms that not only capture data but also ensure that the information can be processed and acted upon by authorities.

Follow-up action and closing the feedback loop

Digital platforms can only improve accountability if reports are addressed and feedback is communicated back to citizens. Evaluations of U-Bridge found only ‘suggestive evidence’ of short-term improvements in education, with no sustained impact into the second year.b766aa314023 Similarly, the World Bank’s Civic Tech in the Global South study found ‘no compelling evidence’ that U-Report had helped Ugandans hold their government accountable.dbab553f6c58

This points to one of the weaknesses of SMS-based accountability projects: without systematic follow-up and institutional responsiveness, citizen reports risk disappearing into a void. The literature suggests that change, when it occurs, is incremental and depends on the interplay between citizens, service providers, and government institutions. Evidence from East Africa shows that mobile monitoring is less a ‘revolution in transparency’ than a slow process of strengthening relationships and trust among actors.974b8b3d321c

Taken together, the evidence shows that digital platforms can expand opportunities for citizen voice, but their effectiveness depends on much more than technology. Without deliberate strategies to engage marginalised groups, mechanisms to ensure data quality, and reliable follow-up to close the feedback loop, such initiatives risk being ineffective. Rather than quick fixes, digital accountability platforms should be seen as part of a longer-term process of strengthening state–society relations, where incremental improvements in trust and responsiveness accumulate over time.

The Olavula platform

From literacy initiative to national accountability tool

‘Olavula’ means ‘dialogue’ or ‘to communicate’ in Makhuwa, the primary Bantu language spoken in northern Mozambique. The platform was conceived in 2013 as a tool to promote access to information and strengthen community communication.3662f8d02bfb It was first incorporated into an existing USAID-funded literacy programme (2014–2019) called Eu Leio (‘I read’),9abc76a0cdc0 whose objective was to contribute to strengthening community engagement in education in four districts of Zambézia province and three of Nampula province to hold school personnel accountable for delivering quality education services, especially as it relates to improving early-grade reading outcomes. Since then, Olavula has been integrated into numerous other programmes run by CESC.

A key vehicle for Olavula’s scale-up was AGIR (Programa de Acções para uma Governação Inclusiva e Responsável), a donor-supported governance programme that funded civil society initiatives aimed at promoting inclusive and responsible governance in Mozambique. AGIR was launched in 2010 (phase I: 2010-2014; phase II: 2015-2020) and was sponsored by Sweden (via Sida) and the Netherlands, with earlier support from Denmark, working through intermediary partners including Diakonia, Oxfam Novib, IBIS/Oxfam Ibis and WeEffect.776559777b73

The programme’s operational phase ended in December 2020 (with final reporting into 2021). AGIR was particularly interested in scalable initiatives, which reinforced an emphasis on expanding Olavula beyond the initial districts, potentially across the country and, over time, into other public services. Olavula has since expanded to around 2,000 registered schools across 15 districts in six provinces (out of 11 provinces, 154 districts and approximately 14,000 schools nationally). Additional support has also come from the United States and from World Vision’s broader education and community engagement work in Mozambique.48d3caf78c70

Institutional architecture and implementation actors

The Centro de Aprendizagem e Capacitação da Sociedade Civil (CESC; the Civil Society Learning and Training Centre) developed and continues to promote Olavula. At its inception, AGIR was particularly interested in initiatives with potential for scale, and the platform was envisioned as expandable to cover the entire country and additional services beyond education. By 2020, Olavula was active in 2,000 schools across 15 districts and six provinces out of Mozambique’s total of 14,000 schools in 154 districts and 11 provinces.fe2e5089eaf6

CAICC, based in the IT department of Eduardo Mondlane University, hosts the platform and manages incoming messages.

Until October 2019, community radio stations played a central role by publicising the platform, airing debates on issues raised, and selecting the most relevant cases to share locally. Radio stations also drew on CESC’s district-level reports to highlight common concerns and stimulate dialogue with authorities.

CESC complemented these efforts through posters, comics, and the training of school-based ‘focal points’ (usually school directors) and community mobilisers, referred to in our research as ‘change agents’. These actors followed up on reported issues, compiled the most pressing concerns for each district, and shared them with local authorities for planning. Mobilisation strategies differed by context: in urban areas, where education levels and mobile phone access are higher, engagement took place directly with service users. In rural or peri-urban areas, school council members acted as intermediaries, collecting concerns from community members – including those without phones or literacy skills – and submitting them to the platform. The aim was to maximise inclusivity and ensure that disadvantaged groups could also lodge complaints.

Citizen reporting and complaint-handling processes

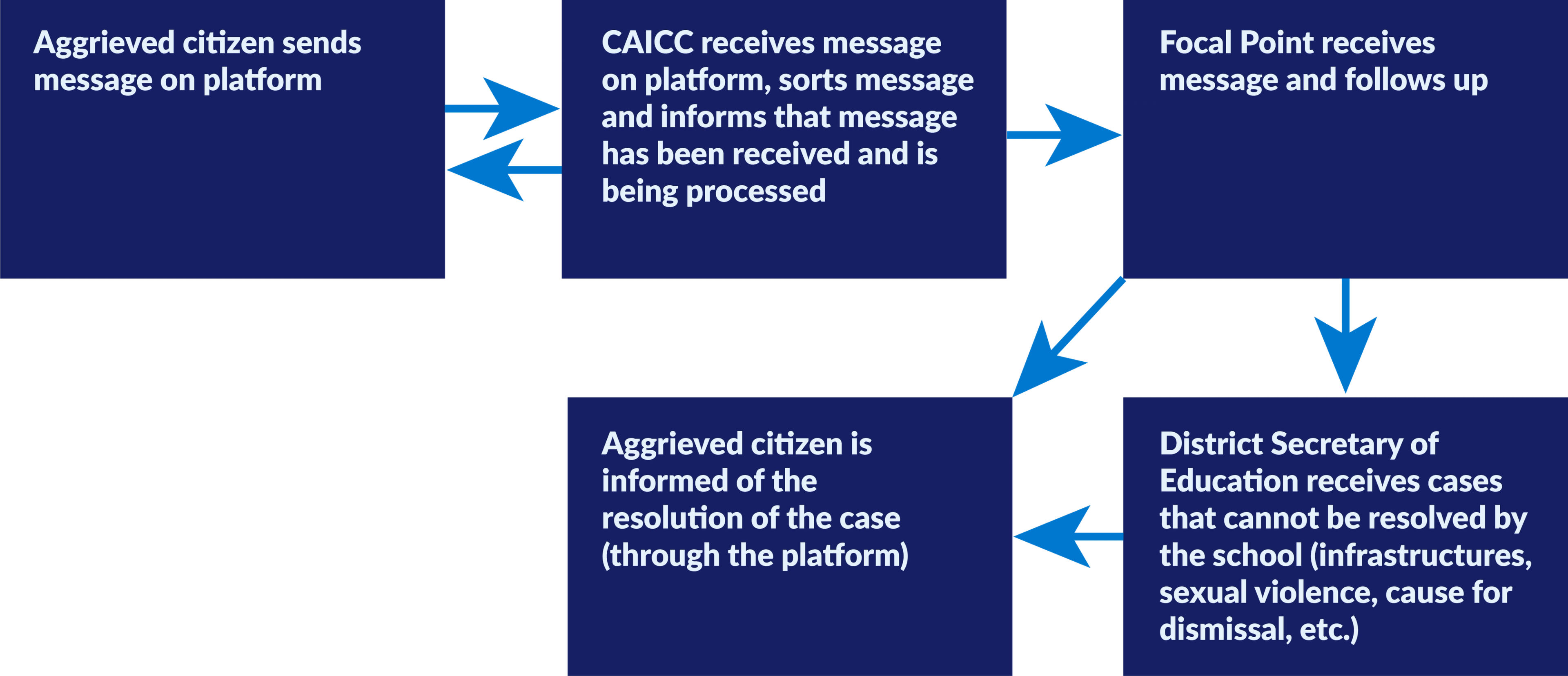

Citizens can submit complaints through various channels, but SMS remains the most widely used. Each participating school designates a focal point, to whom complaints are forwarded. The same messages are also sent to the district education service and provincial education directorate (particularly the inspection department), as schools cannot resolve all issues – especially those related to infrastructure. Every message is assigned a unique code, allowing follow-up and responses to be tracked. Replies are sent through the same medium by which the complaint was submitted, usually SMS, creating a consistent feedback loop (See figure 1).

Figure 1: Complaint process for Olavula

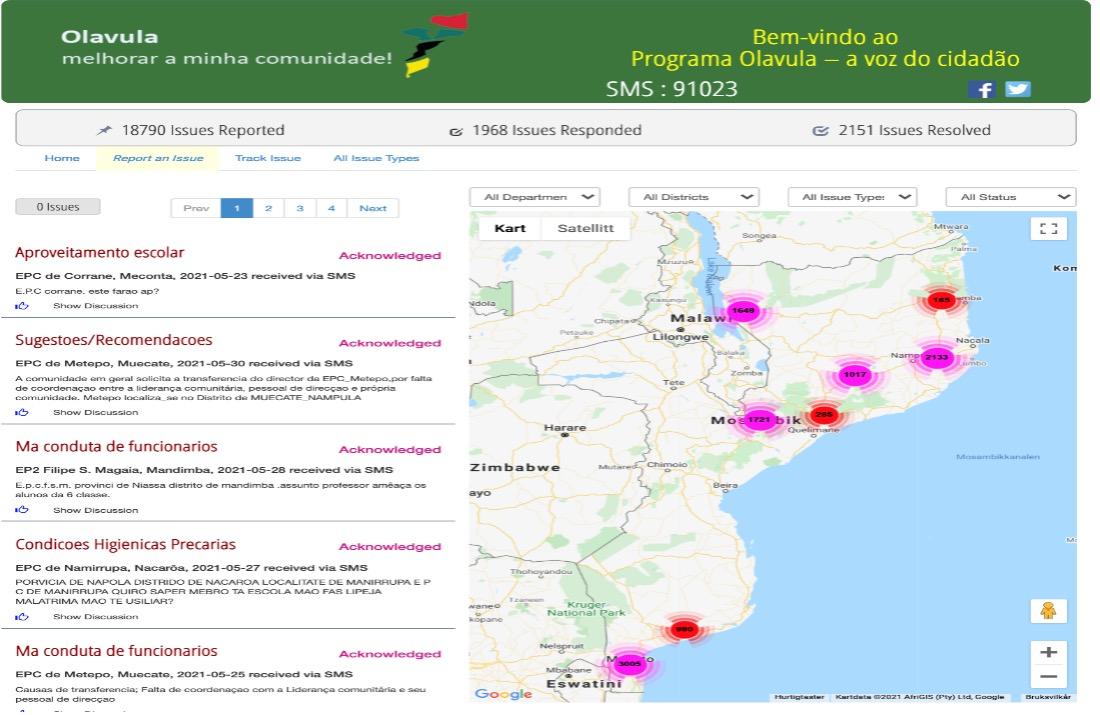

Spatial visualisation and pattern recognition

The complaints are aggregated and displayed on a national map, allowing users to immediately visualise both the geographical distribution and clustering of complaints across the country, as illustrated in Figure 2 below. By plotting individual reports spatially, the interface makes visible regional patterns that may otherwise remain obscured in textual or tabular data, including concentrations of complaints in specific districts or service areas. This visualisation supports rapid sense-making by enabling officials and policymakers to identify potential hotspots, disparities between urban and rural areas, and variations in reporting across regions. As such, the map functions not merely as a display tool, but as an analytical entry point for exploring systemic issues in service delivery and governance.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the Olavula platform showing map-based aggregation of reported issues

Authors’ screenshot of Olavula landing webpage (28 June 2021 at 10.44).

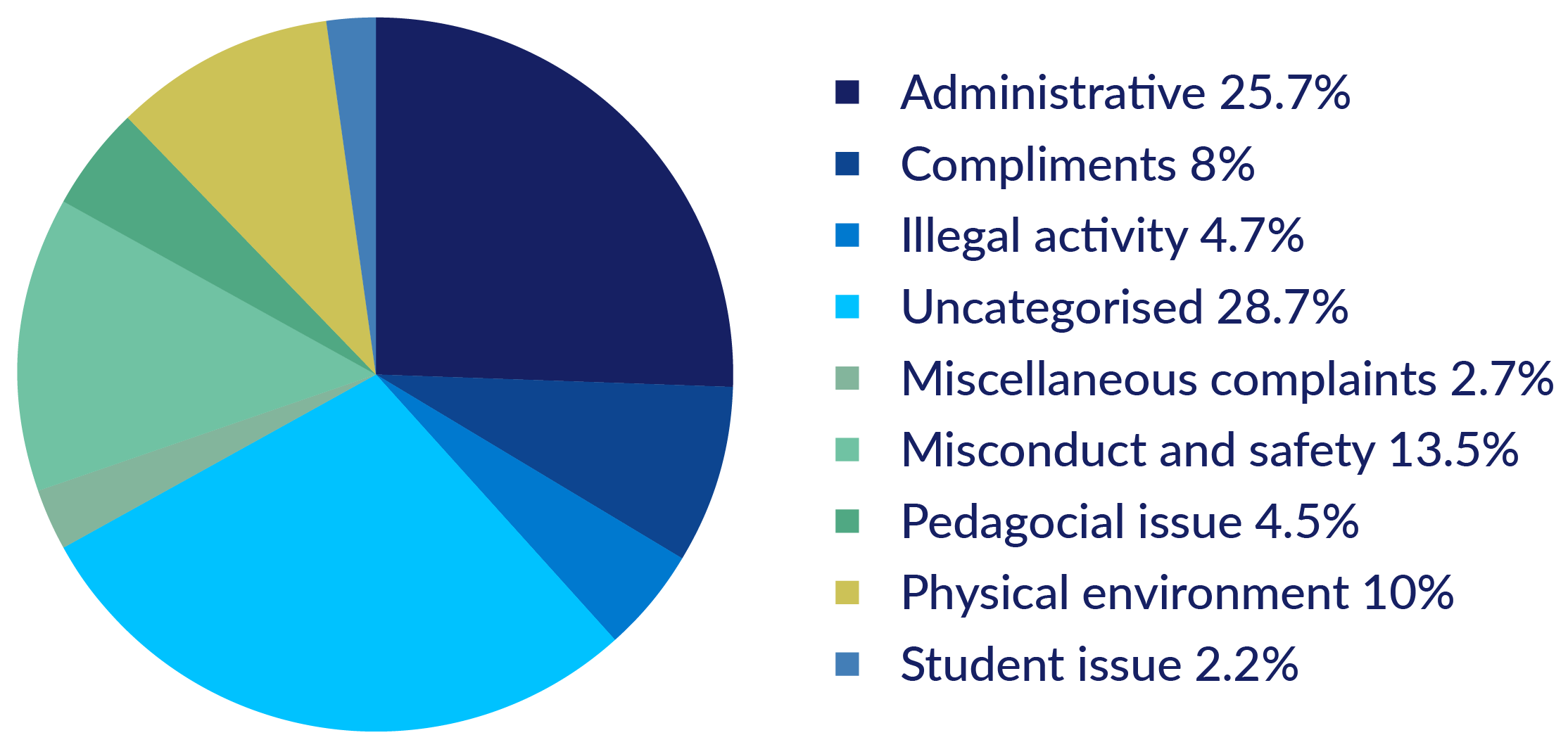

What citizens report: typologies and recurring issues

Our fieldwork analysis from 2021/2 showed 69 complaint categories, which we attempted to group into nine (see Figure 3 below), but further recommend cutting down in future into four main areas for ease of analysis: basic infrastructure, shortages of staff and learning materials, administrative problems, and concerns about misconduct or safety. The most frequently recurring issues were poor sanitation, overcrowded or broken classrooms, lack of furniture, and unreliable access to water and electricity. Parents and teachers also raised concerns about teacher absenteeism, delays in obtaining certificates, or confusion around enrolment procedures. Safety-related reports cited intimidation, disorderly student behaviour, and drug use in or around school premises.83a919e04f32 Notably, the platform was also being used to compliment service providers.

Figure 2: Categories of complaints on the Olavula platform

Authors’ 2021/22 analysis and categorisation of issues.

The pattern of complaints submitted through Olavula suggests that citizens primarily used the platform to report systemic service delivery problems rather than isolated incidents of individual misconduct. Most complaints concerned infrastructure deficiencies, shortages of staff and learning materials, and administrative delays, pointing to persistent capacity and resourcing constraints within the education system. Reports related to misconduct or safety were less frequent and often appeared alongside broader organisational challenges. Overall, the distribution of complaints indicates that Olavula functioned mainly as a channel for highlighting unmet service delivery expectations, rather than as a mechanism for reporting corruption or wrongdoing.

Anonymity and confidentiality in complaint handling

A key feature of the platform is how it handles visibility, confidentiality, and anonymity of messages. Olavula allows parents, guardians, and other community members to submit free SMS reports about school-related issues. These submissions are intended to be anonymous at the point of entry, enabling citizens to report sensitive concerns, including corruption and misuse of resources, without fear of reprisal.a4a420ceb2c8

In principle, the portal distinguishes between messages that can be shared more broadly and those that must remain confidential or be handled through specialised channels. For example, physical and sexual abuse cases are not published on the portal in order to protect complainants’ confidentiality; they are also not routed directly to school focal points but are instead sent to the district education service because they are treated as public crimes and to limit the spread of unsubstantiated rumours.

Nonetheless, during fieldwork, we found that several such reports have appeared on the public portal, indicating that in practice there can be leakage between confidential and public streams. This mix of anonymity at submission, differentiated visibility, and occasional public display of messages reflects ongoing dilemmas about where the balance should lie between transparency and privacy.f45dcc98dee1

Factors that have contributed to Olavula’s success

Anecdotal evidence from this study indicates that Olavula has contributed to greater transparency, participation, and accountability in Mozambique, particularly at the local level, though evidence of impact at central government level remains limited. Respondents reported that the platform has encouraged closer scrutiny of school accounts and expenditures, and has served as a performance monitoring tool. School directors noted that Olavula enables them to gauge whether communities view their performance positively or critically. Respondents also perceived that the platform has helped reduce absenteeism among both teachers and students,100a6ce4905b and in some areas has even provided a channel to denounce early marriage.5e53d21efbd5

Several factors appear to explain this positive feedback and the perception of impact at community level. These include Olavula’s integration into a broader literacy programme; strong buy-in and ownership by stakeholders; its accessibility and ease of use; the guarantee of anonymity; and consistent response and follow-up mechanisms.

Integration of Olavula, and achieving buy-in and ownership from actors

Olavula has been integrated into literacy and education improvement programmes, which has fostered buy-in and made school administrators and teachers more receptive to using the platform.1d1debe962e3 Respondents highlighted strong support among school directors, who are the primary recipients of messages, and one district secretariat staff member praised the programme for contributing to children’s literacy gains. This suggests that framing digital platforms not solely as complaint or grievance mechanisms, but as part of broader efforts to improve literacy and education outcomes, can enhance ownership and acceptance by communities, school staff, and public officials alike.

A wide range of actors has been involved in Olavula. Under the Eu Leio programme, platform managers received and published messages on the website; community radio stations publicised the tool and discussed locally relevant issues; school-based focal points received and responded to messages; facilitators trained users and supervised activities; and change agents mediated between the platform and communities while sharing information more broadly. Monitoring teams consolidated data and, together with provincial and district officials, visited schools and followed up complaints to ensure resolution.

Overall, these actors expressed positive views and a sense of ownership. However, despite CESC’s efforts, by late 2019 and early 2020 the Ministry of Education had not assumed responsibility at the central level. Officials reported that rules for responding to complaints – such as which messages could be publicised, expected response times, and the responsibilities of school managers – were still under development. Even in 2024, after nearly a decade of operation, ministry buy-in remained elusive. CESC has now concluded that Olavula would be better managed by an independent civil society organisation than under unenthusiastic government stewardship.

At the local level, CESC promoted buy-in by reassuring district and school officials that Olavula was a tool for dialogue with parents and communities, not simply a channel for criticism. As one focal point observed: ‘once the person understood that the platform was not there to criticise, then they could see that it really helped with the job.’ Some communities, meanwhile, have embraced Olavula as a trusted way to voice their concerns and needs,b4319bbc6aca although anecdotal evidence from interviews shows that sustained use is more likely in areas where Olavula has an additional offline/in person component.

Accessibility and user-friendliness

Although Olavula is web-based, the vast majority of messages have been submitted by SMS. From the outset, the platform adapted to local conditions and learned from user behaviour to improve accessibility. For example, the original contact number to which people had to send their message was too long and hard to memorise. Uptake increased significantly once it was replaced with a shorter, toll-free number. The fact that it was free was also critical, given that the cost of 1 GB of mobile broadband data was very high relative to income, amounting to about 7 per cent of average monthly earnings for the typical Mozambican consumer.1b7c0b100e78

Most schools in Mozambique maintain physical complaint boxes, but these are only accessible to parents and community members who interact directly with the school, and follow-up is often weak. Olavula, by contrast, has enabled participation from community members who rarely engage with the school, while also guaranteeing anonymity. As one respondent explained: ‘there are parents who live near the school and would not interact with the school because they feared reprisals. With the platform they feel free because one does not know which parent [complained].’ In this way, digital platforms can be more inclusive than analogue mechanisms such as complaint boxes or committees.

A key safeguard is that the sender’s personal data is not shared with the recipient, protecting complainants from retaliation and enabling them to voice concerns freely. However, anonymity also creates challenges. Some focal points noted that they were unable to respond to certain complaints because they did not know who the sender was and could not follow up for additional details. In some cases, complainants inadvertently revealed their identity by signing their messages.

CESC is currently working on an updated version of the platform to address these weaknesses. Planned improvements include ensuring that personal data is not visible on the web version, introducing a dashboard for simpler tracking of submitted and resolved cases, enabling the use of voice messages to improve access for illiterate users, and integrating the service with WhatsApp.

Response and follow-up

Respondents emphasised that one of Olavula’s strongest features is the responsiveness of the system. Once a concern is uploaded, users typically receive an acknowledgement, followed, in most cases, by another message when the school’s focal point replies. This process gives users a sense of efficiency and satisfaction, reinforcing their trust in the platform.

Behind the scenes, a team of helpdesk managers, facilitators, and change agents compiled the data and ensure follow-up at the district and school levels. Communities within school catchment areas were also consulted, which not only empowered parents and local residents but also created a greater sense of accountability among public officials. For community members, hearing about complaints that had been positively addressed, even when it was in neighbouring schools, was reassuring and reinforced confidence in the system.

A further factor promoting accountability is that the complaint manager, CAICC (on behalf of CESC), operates as an independent body rather than as part of the school or government. This external oversight has helped ensure impartiality and CAICC has demonstrated a strong commitment to seeing issues through to resolution.

It is however, important to clarify what “resolved” means in the platform’s reporting system. In practice, a complaint is typically classified as resolved once an authority has issued a response or taken note of the issue, rather than when the underlying problem has been substantively addressed or remedied. This distinction is critical in interpreting the platform’s aggregate statistics: in the 2021 dashboard as shown in Figure 2, only about 10.5% of registered complaints were marked as “responded”, and 11.4% as “resolved”, despite nearly 19,000 issues having been reported overall.840e13f3a096

Respondents we interviewed indicated that many complaints, particularly those relating to infrastructure deficiencies, were redirected to individual schools, with the implicit expectation that parents, guardians, and local communities will mobilise their own resources to address the problem. In such cases, the platform functions less as a mechanism for service delivery or enforcement, and more as a channel for notification and administrative signalling. While this approach may support visibility and basic accountability, it also helps explain the persistently low proportion of issues formally responded to or resolved: responsibility for action is effectively devolved away from district or central authorities, and “resolution” is independent of material improvements on the ground.

A closer reading of the data suggests that Olavula functions primarily as a digital feedback and monitoring platform, rather than as a mechanism for resolving complaints. Its core strength lies in capturing, categorising, and visualising citizen reports, thereby increasing visibility of systemic problems in the education sector. The consistently low share of responded and resolved cases indicates that the platform is not institutionally linked to enforcement, budgeting, or corrective action. Responsibility for follow-up is largely devolved to schools, districts, or communities, meaning that citizen voice is recorded but not necessarily translated into remediation. The gap between reporting and resolution therefore reflects structural accountability constraints, not a failure of the technology itself.

Challenges faced by Olavula

Even though Olavula has contributed to some improvements, the platform continues to face challenges that limit its potential. The main obstacles include limited phone and internet connectivity, low levels of digital literacy, and weak data management capacity.

Limited phone access and internet connectivity

Despite gains in mobile penetration, large parts of Mozambique remain unconnected. In many communities, people relied on change agents acting as intermediaries to relay their concerns to the platform. These agents typically followed a set schedule to visit schools, markets, and churches within their catchment areas. Respondents observed that schools in areas with poor connectivity received fewer complaints, while more urbanised districts generated the highest volume of cases, as reflected in the geo-tagged platform data.

Smartphone ownership remains particularly low. A recent report on ICT access in Mozambique found that only 40% of Mozambicans have access to mobile phones, and just 10% have access to the internet.5bfbe1b8805f As a result, the vast majority of messages are submitted via SMS.

Gender disparities compound the problem: according to the 2019 Mobile Gender Gap Report, 60% of men in Mozambique own a mobile phone, compared with just 45% of women, and only 9% of women have mobile internet compared with 22% of men.d977a3d157a6 Higher female illiteracy rates further reduce women’s ability to engage directly with the platform, forcing many to rely on intermediaries, thereby undermining the advantage of anonymity.

Several practical limitations were also identified. Focal points often receive Olavula messages on their personal phones, where they become mixed with private communications. As one respondent explained, once an initial reply had been sent, it was difficult to locate the original message later: ‘If I don’t get an immediate response, the message is buried among my personal SMS, and I can’t find it again.’

Connectivity gaps also mean that constant reminders are required to maintain community engagement, through outreach visits or radio announcements, for example. However, with the end of the original programme and its funding, change agents stopped their visits and radio spots were discontinued. One school resorted to placing posters on its walls, but their impact was limited if parents did not regularly drop off or collect their children.

Although Olavula has since been integrated into other programmes, follow-up activities such as training and mobilisation now depend on the geographic focus of new development partners, which does not always align with earlier coverage. What has remained constant is the backstopping role of the platform managers at CAICC, who continue to channel messages to focal points regardless of whether a school or district is part of a currently funded programme. Once a school is registered and a focal point trained, it remains on the platform even if programme funding ceases.

Data management and technical capacity

One challenge that has emerged is protecting the identities of both users and service providers, particularly in cases involving allegations against individual teachers or officials. In the pursuit of transparency, there is a risk that data compromising a complainant’s safety, or publicly accusing individuals without due process safeguards, may be published. To address this, the platform managers at CAICC and the Ministry of Education held discussions on which types of messages should be made public and which should remain confidential.

A second, related challenge concerns limited management and analytical capacity. As noted above, the platform operated with an extensive classification system of 69 complaint categories, (which we subsequently rationalised into a smaller number of analytically meaningful groupings). Platform managers reported that they lacked sufficient staff to process and analyse the volume of messages received, and the proliferation of overlapping or duplicative categories further compounded this constraint. Although the classification framework was intended to mirror Ministry of Education monitoring standards, in practice it hindered effective data management and analysis. Instances of misclassification were also observed, for example, reports of sexual misconduct recorded under infrastructure-related categories. This illustrates the risks associated with a complex taxonomy in the absence of adequate analytical capacity and points to a clear need for both simplification of complaint categories and targeted capacity building in the sociological coding and analysis of complaints data, to improve accuracy and enhance the platform’s utility for monitoring and accountability.

Olavula’s unexplored potential

Olavula illustrates how a digital platform, despite facing significant challenges, can play a modest but meaningful role in improving service delivery and accountability. With stronger support and enhanced technical capacity for data management and analysis, it has the potential to make a greater contribution to Mozambique’s education sector. At the same time, the widespread normalisation of corruption in Mozambique and of public apathy towards corrupt practices may constrain its effectiveness as a tool for accountability and anti-corruption.58856971ed66

The platform has primarily targeted primary schools, where opportunities for corruption are relatively limited because tuition fees are not charged. Nonetheless, there have been isolated examples of suspected embezzlement and mismanagement of school funds. Respondents, however, often attributed these cases to poor transparency rather than outright misappropriation.

There remains considerable untapped potential for Olavula to address opacity and corruption more directly. For example, it could support public expenditure tracking by publishing allocations to schools, amounts received, and expenditure patterns.f09a3ca8e11f Adding a social audit component, through which citizens can verify that funds are used as intended, would further strengthen accountability.5a51a5944f58

Olavula could also do more to foster civic participation and promote a culture of democratic accountability. Currently, focus on schools means that complainants have little direct engagement with district-level officials (see Figure 1 on the complaints process), which limits opportunities for dialogue. This is a missed opportunity to strengthen relationships between citizens and public officials. Comparative experience, such as the uSpeak programme in Uganda, shows the potential of SMS-based platforms to enhance engagement. In uSpeak, constituents shared views via SMS, voicemail, or call centres, and members of parliament received aggregated reports by topic.d1cc7415225e An evaluation found that this approach successfully broadened participation among marginalised groups and increased politicians’ awareness of their constituents.72fb32516a75

Olavula also functions as a repository of valuable data on education service delivery, with georeferenced complaints that could serve as a monitoring and evaluation tool. Such data could provide rapid insights into hotspots and allow for localised, context-specific solutions. At present, this potential remains underutilised. Linking Olavula data with census and population statistics, or adding a timeline function, could help track how problems and responses evolve over time. Similar tools are already used in disaster response95df6a7eefa1 and election monitoring634aef1e73fa to map incidents, resources, and outcomes.

For Olavula to achieve greater impact, it will need to scale up strategically, integrate these additional functions, and ensure long-term sustainability as it plans for its next phase.190e1fa495b1

Recommendations

The findings from Olavula highlight what community-led digital reporting platforms can achieve in fragile and politically constrained settings: they can meaningfully amplify community voices and strengthen local-level transparency. At the same time, the case surfaces some constraints that are likely to travel across similar contexts, particularly around institutionalisation, technical capacity, and inclusive participation. The recommendations below therefore draw on lessons from Olavula that could inform the design, resourcing, and scaling of comparable platforms in fragile contexts.

Address access and inclusion gaps. Connectivity, literacy, and gender disparities limit uptake. Combining digital with offline engagement strategies, targeted outreach to women and rural poor, and alternative complaint channels (voice, WhatsApp, community agents) could broaden participation.

Simplify complaint categories and strengthen data management capacity. The current classification system is overly complex and inconsistently applied, constraining effective management and analysis of complaints data. Future iterations of the platform should consolidate categories into a limited number of analytically meaningful groupings such as basic infrastructure; staffing and learning materials; administrative and governance issues; and misconduct, safety, or abuse; to improve usability and reduce misclassification. This simplification should be accompanied by targeted training for platform managers in complaint coding and triage, as well as enhanced dashboard functions to support aggregation and trend analysis. Investing in sociological and qualitative data analysis capacity is essential to ensure accurate classification, enable meaningful monitoring, and strengthen the platform’s contribution to planning, oversight, and accountability.

Ensure responsiveness and feedback. Sustained citizen engagement depends on seeing results. Mechanisms to update complainants via SMS or community channels should be institutionalised, with systematic follow-up and monitoring of response times by district and provincial authorities.

Expand accountability functions. Olavula has untapped potential for expenditure tracking, social audits, and georeferenced monitoring of service delivery. Future investments should expand its analytical use, linking complaints to budget allocations and policy decisions.

The additional recommendations below draw on comparative examples, not just the Olavula research, and broader lessons from digital accountability platforms:

Sustain advocacy and citizen mobilisation. The concerned agencies should continue awareness campaigns to build trust in the platform and prevent declining participation over time. Encourage citizen ownership to maintain pressure on government for improved service delivery.

Provide clear guidance on complaint processes. Adding step-by-step instructions for users will help to ensure complaints are specific, actionable, and reach the right authority, which is important for improving citizen engagement.

Provide further guidance and a safe reporting channel for corruption-related complaints. Although corruption is not an explicit focus of Olavula, complaints occasionally touch on it. To strengthen the platform’s ability to address such cases, Olavula can take inspiration from good practices in other countries where citizen-facing public-service platforms include structured reporting pathways, clear escalation steps, and safe channels for sensitive complaints. For example, Rwanda’s IremboGov platform provides accessible guidance and contact points for reporting misconduct linked to service delivery, including options for escalation when frontline responses fail. Similarly, Kenya’s Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) operates multiple public reporting channels – including a secure online form, walk-in centres, and toll-free hotlines – for education- and service-related corruption. These models illustrate the importance of giving citizens simple, well-publicised instructions on where to report concerns, multiple reporting modalities, and escalation routes when initial steps do not resolve the problem.

Invest in infrastructure, personnel, and long-term support. Scaling up digital solutions increases costs and requires continuous investment in personnel, infrastructure, and multi-actor coordination. Development partners should plan for long-term support until national systems are robust.

Protect data and whistleblowers. Olavula currently lacks adequate protections, leaving individuals vulnerable to serious personal and professional consequences if exposed. Such platforms there need robust security features and protocols to prevent identification, alongside clear safeguards to protect those implicated in complaints. Capacitybuilding is also critical, therefore both platform managers and user communities should receive training on data protection, privacy rights, and whistleblower safeguards, in line withMozambique’s Witness Protection Act.bb8442b94133

Expand data collection and triangulation. The data collected through Olavula could be strengthened and validated through complementary methods such as SMS polls and mobile hotlines. A useful example is the mobile polling platform Sauti za Wananchi (‘voice of the people’), used by an East African civil society organisation named Twaweza to monitor health and education services. Through a representative sample of randomly selected households, some of which are equipped with mobile phones and solar chargers, Twaweza gathers survey data on issues such as drug shortages and literacy levels. These findings are then triangulated with budget and financial information, as well as individual complaints, to trigger accountability processes.67c1198349fb Similar investments in Mozambique by development partners, civil society, and government could enhance Olavula’s dataset, generating more reliable evidence for policy reform and improved service delivery.

Conclusion: the potential of digital platforms

Olavula’s experience shows that digital feedback platforms can amplify community voices and improve local-level transparency, but their impact ultimately depends on sustained institutional responsiveness, inclusive design, and robust data practices. In Mozambique’s decentralised and resource-constrained context, the platform has demonstrated tangible contributions where complaints are acknowledged, acted upon, and responses communicated back to citizens.

However, the case also reveals the limits of such interventions, particularly when connectivity, capacity, and ownership are weak. It shows that digital tools are not standalone solutions but part of a longer process of building trust between citizens and the state. With continued civil-society stewardship, government oversight, and predictable, long-term support from partners, Olavula can evolve from a complaints mechanism to become part of the sector infrastructure for accountability, helping to embed more responsive service delivery and, over time, contributing to improved anti-corruption outcomes in education.

- Field work was derailed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Centre for Public Integrity, which is the Transparency International chapter in Mozambique.

- National Forum of Community Radios, representing and supporting community radio stations.

- [1] Centre for the Support of Community Information and Communication. CAICC manages the Olavula platform and is based at the IT department of Eduardo Mondlane Univeristy, Mozambique.

- Civil Society Learning and Training Centre, who are the implementing agent.

- Goodchild 2007.

- Participedia, n.d.

- https://ureport.in

- Holtom et al. 2022.

- Grossman et al. 2018, 2020.

- Kerkvliet et al., 2024; Holloway & Lough 2020.

- Grossman et al. 2017.

- Grossman et al. 2018.

- Peixoto and Sifry 2017.

- Georgiadou et al. 2014.

- IIEP-UNESCO 2025.

- USAID-funded Eu Leio (‘I Read’) was implemented between 2014 and 2019, focusing on early-grade reading and parental participation in education. See USAID (2014).

- Information obtained from respondents at CESC. See also: WeEffect (2025).

- World Vision’s community-led education support in Mozambique has included literacy engagement and local advocacy training, as reported by World Vision. See World Vision (2025).

- This has now (2025) expanded to 2,660 schools in 30 districts.See IIEP-UNESCO (2025).

- A recent (2025) analysis suggests that by 9 April 2025, the Olavula Platform has received 23,295 messages, with some 2,198 successfully resolved; compared to around 10,920 in 2021-22 when we did our fieldwork. This indicates a substantial increase in the platform’s accessibility and usage over the past 3 years. See UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) (2025) Text your education challenge: Mozambique’s Olavula platform.

- UNESCO-IIEP (2025), above.

- Detailed platform documentation on exactly which types of messages are published and the technical mechanism for enforcing confidentiality is not publicly available; the description is based on our fieldwork findings and available secondary sources. See also UNESCO - IIEP (2025) above.

- However, since there was no baseline information on the rate of such marriages, it would be difficult to determine whether Olavula is indeed having such as impact.

- In a 2014 World Bank Service Delivery Survey, Mozambique showed high rates of student absenteeism from school.

- The larger ‘Eu Leio’ programme had several objectives. It worked with teachers to improve their speaking, reading, writing, and teaching skills. It also included gender sensitisation. Eu Leio also worked with managers on pedagogical supervision and community engagement, through the Olavula platform. It also trained school councils on participation, monitoring, and supporting school management. At community level it worked with parents and traditional leaders to prevent early marriages.

- UNESCO-IIEP (2025).

- Based on The State of ICT in Mozambique (Gillwald, Mothobi & Rademan 2019), 1 GB of mobile data cost roughly 7 per cent of average monthly income in Mozambique.

- The relatively low share of responded and resolved complaints, when compared to the total volume of issues submitted, does not appear to be an anomaly of the 2021 snapshot. As suggested by later visualisations on the UNESCO IIEP webpage from 2025, this gap between reporting and follow-up appears broadly consistent over time. This persistence points to a structural feature of the Olavula model linked to its classification logic, routing of complaints, and reliance on community self-help rather than to short-term implementation weaknesses alone.

- Gillwald et al. 2019.

- Rowntree 2019.

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) (2022).

- Reinikka and Smith 2004.

- Farag 2018; see also Carmago 2018.

- See Grossman et al. 2018.

- NDI 2012.

- Bloch 2016.

- Ushahidi 2024.

- UNESCO-IIEP (2025).

- Republic of Mozambique. 2012. Witness Protection Act.

- Twaweza (2024).