Query

Please provide an overview of recent developments with regards to corruption and anti-corruption in Cuba, with a focus on the military, state-owned enterprises and illicit financial flows (IFFs).

Caveat

Due to the closed nature of the country, it is difficult to find systematically gathered data on the extent and nature of corruption in Cuba. To overcome this challenge, this Helpdesk Answer also relies on case-based evidence.

Background

Since 1959, Cuba has functioned as a one-party state under the rule of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), the sole political entity recognised by the constitution. Furthermore, competitive elections, opposition parties and independent oversight institutions are not permitted. Following a sustained period of rule under Fidel Castro and subsequently his brother Raúl Castro, Miguel Díaz-Canel assumed the role of first secretary of the PCC in 2021. Díaz-Canel was first elected president of Cuba in 2019 and was re-elected in 2023 to serve until 2028 (Reuters 2023). In addition, in 2019, Cuba appointed its first prime minister in over 40 years – former tourism minister Manuel Marrero Cruz – marking a significant shift in the country’s political dynamics (BBC 2019).

However, international observers continue to classify Cuba as a highly authoritarian regime, lacking fundamental civil and political liberties (Freedom House 2025; Varieties of Democracy 2023:41). Substantive power remains concentrated within the PCC elite and strategic sectors are controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR). The FAR comprises the army, the revolutionary navy, the air and air defence forces, the youth labour army, the territorial troop militias, and the production and defence brigades, and is organised into three regional commands: western, central and eastern (Tedesco 2018:112).

The FAR plays a pivotal role not only in governance but also in the Cuban economy through the Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A. (GAESA), a military controlled business conglomerate established in 1995. GAESA operates beyond the scope of civilian oversight as it is administratively subordinated to the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (MINFAR). In accordance with the First Special Provision of Law No. 158 of 2022 (published in 2023), all auditing, supervision and control functions concerning the MINFAR and the Ministry of the Interior (MININT) – which oversee GAESA – are carried out under their own internal regulations (elToque 2024).

Leadership of GAESA passed from General Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Calleja – a close relative of Raúl Castro – who died in 2022, to Colonel Ania Lastres Morera, maintaining continuity of military control over major revenue generating sectors (PCC 2025).

Despite limited reforms, Cuba’s economy remains centralised and state-controlled. The former dual currency system – previously involving the Convertible Peso (CUC) – has transitioned to a hybrid model based on the Cuban Peso (CUP) and the Moneda Libremente Convertible (MLC), a foreign currency-denominated mechanism. This monetary structure is not market-driven but centrally managed by the state, which determines exchange rates, controls access to MLC accounts and restricts the circulation of hard currency. Commentators argue this arrangement has exacerbated socioeconomic disparities, promoted partial dollarisation and expanded informal market dynamics (La Joven Cuba 2021; Cuba Siglo 21 2023).

A significant development in Cuba’s economic landscape was the formal legalisation of micro, small and medium-sized private enterprises (MiPYMEs) beginning in 2021. Although an emerging class of self-employed workers (cuentapropistas) had existed prior to this reform, the recognition of MiPYMEs marked a notable departure from the orthodox principles of the socialist economic model (Andarcia 2021). Under the current legal framework, private enterprises are permitted to employ up to 100 workers, with any expansion beyond this limit explicitly prohibited (vLex 2021). Despite their formal recognition, these businesses continue to face substantial operational constraints, including restrictive regulatory conditions, limited access to foreign currency and formal supply chains, and complex, often burdensome, licensing requirements (vLex 2021).

As of 2025, Cuba is undergoing a severe and prolonged economic crisis, exacerbated by the collapse of Venezuelan support, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, uncontrolled inflation and long-standing structural inefficiencies (Vidal 2025). The July 2021 protests marked a significant turning point. Thousands of Cubans took to the streets demanding greater freedoms and improved living conditions. The state responded with swift and repressive measures, including widespread arbitrary arrests and the criminalisation of dissent (Amnesty International 2025:175; Human Rights Watch 2025; UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention 2024:17).

This Helpdesk Answer explores the state of corruption and anti-corruption in Cuba, including by considering how these have been affected by the recent developments outlined in this section.

Drivers of corruption

Considering the political context and prevailing socioeconomic conditions in Cuba, several structural factors can be identified as key drivers of corruption.

State and military monopoly over the economy

Cuba’s economy remains dominated by the state and, in strategic sectors, by the military through the business conglomerate GAESA. GAESA controls entities in tourism, retail, logistics, banking, remittance processing and infrastructure. These entities manage a substantial portion of hard-currency transactions (BTI 2024:20 ; OCIndex 2023:6).

GAESA’s internal architecture fosters systemic risks. For example, vertically integrated operations, such as military construction companies building facilities later managed by other GAESA subsidiaries, lead to internal contracting without competitive bidding or transparency (BBC 2017).

According to various reports, the conglomerate GAESA is not merely managed by ordinary military personnel but is controlled by a select group of senior military officials closely tied to the executive power and ruling elite. Notably, relatives of Raúl Castro are beneficial owners of entities spanning telecommunications, finance, real estate and energy sectors (DW 2018). This concentration of control has reportedly facilitated the emergence of a parallel economy aligned with elite interests, operating with limited public scrutiny or institutional oversight (CONNECTAS 2020).

Scarcity and survival corruption

Cuba’s economy operates under conditions of systemic scarcity, with persistent shortages in food, medicine, fuel and housing exacerbated by inflation, US sanctions and long-standing policy failures. These shortages normalise different ways of corruption as a mechanism of survival. Public-sector workers, unable to meet basic living standards on official salaries – averaging US$48.60 per month in 2024 (Swissinfo 2025a) – often resort to the diversion of state goods and the informal resale of subsidised or rationed products (BTI 2024:15). The situation has reportedly been deteriorating and in 2024, Cuba requested urgent assistance from the United Nations for the first time to help supply milk for children (El País 2024).

In some cases, this scarcity may drive forms of petty corruption. A 2017 case revealed the theft of cement valued at almost US$5 million from government stores for clandestine resale, disrupting the state’s construction supply chain(CiberCuba 2017). Similar patterns are observed in the healthcare and energy sectors, where medications and petroleum products are routinely siphoned off and traded through black-market networks (CubitaNOW 2025; CiberCuba 2024a; Martí Noticias 2023). According to the Organised Crime Index (OCIndex), frontline workers in distribution chains, such as gas station employees and hospital staff, frequently engage in small-scale corruption, facilitated by a culture of impunity and institutional complicity (OCIndex 2023:3).

Small bribes are used to obtain basic needs such as medical attention, vehicle repairs or school enrolment. In sectors like education, tutoring has become privatised informally, with teachers offering after-hours paid sessions to supplement their incomes (Diario las Américas 2018). The rationing system given by the government, although universal, covers only a fraction of monthly needs, further incentivising illicit trade and informal bargaining.

Some reports argue that the societal normalisation of these practices – locally referred to as la lucha (the struggle) – has generated a corruption-permissive culture where circumventing rules is widely tolerated as a necessary survival tactic (La Joven Cuba 2024).

Clientelism and patronage networks

Cuba’s single-party system eliminates political pluralism and concentrates authority within the PCC. In this centralised structure, political loyalty is often rewarded with access to public office or economic privileges; for example, there are no public bidding processes for many projects seeking access to state resources or infrastructure (BTI 2024). In 2024, President Díaz-Canel publicly recognised and condemned corruption in state-owned companies, as well as ‘influence peddling’ in their contractual relationships with the private sector (Swissinfo 2024b). Clientelism and political loyalty may determine public contracting outcomes. In 2023, the Asamblea de Cineastas Cubanos publicly denounced the state of the cultural sector in Cuba, alleging state support and recognition are selectively granted based on loyalty rather than merit (Martí Noticias 2024; Diario de Cuba 2023).

Local official discretion and the emerging private sector

In 2021, privately-owned small and medium enterprises (MiPYMEs) were first legalised in Cuba; subsequently more than 9,000 such entities were soon established (Swissinfo 2023). However, this emerging private sector remains tightly constrained and dependent on state structures. Private entrepreneurs must obtain approval from municipal authorities, as stipulated in Article 18 of Decree-Law 88/2024. Furthermore, these businesses cannot import goods directly and must instead rely on state-authorised entities, as outlined in Resolution 38/2023. Access to wholesale markets and essential resources is also limited, with Resolution 56/2024restricting private-to-private wholesale transactions (Granma 2024b).

This asymmetry can reportedly create incentives for bribery and favouritism (Cuba Siglo 21 2024). Local officials often exert discretionary power in granting approvals, with little oversight. According to Torres Pérez (2024a; 2024b), the lack of wholesale markets may lead MiPYMEs to acquire required resources through informal channels, some involving corrupt arrangements with state employees. Tax burdens and regulatory complexity further expose small businesses to extortion. As noted in the OCIndex (OCIndex 2023:4), many private actors evade taxes or operate partially in the informal sector, not only due to evasion but in order to circumvent state-imposed barriers (Periódico Cubano 2025a).

In recent years, commentators have also highlighted the increased use of state rhetoric, including statements by Prime Minister Manuel Marrero Cruz, blaming the private sector for economic distortions and alleging ties with corrupt former officials (CiberCuba 2024b).

Remittances and financial opacity

Remittances, estimated at over US$3 billion annually, are a vital source of income for many Cuban households (WOLA 2022). Between 2005 and 2020, remittances represented approximately 8.3% of Cuba’s GDP (Pavel Vidal 2022). However, these inflows are funnelled through state-controlled mechanisms that operate with minimal transparency.

Following US sanctions in 2020 against the Cuban financial institution Fincimex that operated Western Union exchange services on the island, the Cuban government established Orbit SA, a nominally civilian enterprise intended to manage remittances. However, investigations revealed that Orbit SA functions as a de facto extension of Fincimex, operating from the same facilities and managed by the same personnel. This continuity was confirmed in early 2025, when Orbit was added to the list of US sanctioned entities (Nuevo Herald 2025).

According to some sources, the absence of public transparency regarding remittance volumes, fees and exchange rates facilitates misappropriation and arbitrary deductions, allowing actors to capture a disproportionate share of these funds while diminishing the real value received by Cuban residents (IWPR 2021; The Inter-American Dialogue 2024:11).

This financial opacity extends to so-called MLC stores, which sell imported goods exclusively in foreign currency at significantly marked-up prices. Revenues from these stores are not publicly reported (elToque 2021). This arrangement exacerbates socioeconomic inequality as only individuals with access to remittances or foreign income can purchase goods in these outlets, while the majority, reliant on devalued pesos (CUP) are excluded from accessing essential products (Reuters 2022).

Additionally, the disruption of official remittance channels due to US sanctions has spurred the growth of informal money transfer methods (Representaciones Diplomaticas de Cuba en el Exterior 2025). An increasing number of Cubans now send foreign currency through private intermediaries found on social media, who charge commissions of approximately 10 per cent. These informal operators often offer more favourable exchange rates aligned with the informal market, making them a more attractive alternative despite the lack of regulation (Swissinfo 2025). The rise in physical currency transfers across borders underscores both the population’s lack of trust in official channels and the persistent demand for financial alternatives that circumvent state-controlled systems.

These funds, however, do not always enter the country in foreign currency but as electronic credits (MLC) that can only be spent in GAESA controlled retail stores. This closed-loop system allows the Cuban state to capture the full value of remittances, while imposing high markups on basic goods (The Inter-American Dialogue 2024). According to a 2024 study by The Inter-American Dialogue, following Western Union's exit from Cuba due to US sanctions, 100% of remittances between 2020 and 2022 were sent via mules or travellers. This figure dropped to approximately 40% from 2023 onwards, following the rise of Orbit, a financial intermediary not subject to OFAC restrictions in those years (The Inter-American Dialogue 2024:10). These informal money transfer methods lack oversight and verification mechanisms which may create a risk they facilitate transnational illicit financial flows (IFFs).

Moreover, these informal practices have fuelled the growth of a parallel currency market in Cuba. In addition to official exchange houses, there exists a robust street market for buying and selling foreign currencies at black-market rates that diverge significantly from the official rate. This parallel system allows people to buy or sell US dollars at freely negotiated rates in CUP, creating a shadow financial market that encourages and enables illicit economic activity. This parallel dollar is fully legitimised, and its exchange rate is publicly distributed through both online platforms and official media channels (CiberCuba 2025a).

Together, these factors have created a dual-track remittance ecosystem: one opaque and state-managed, the other informal and largely unregulated, both lacking institutional safeguards and susceptible to exploitation. This fragmented and uncertain landscape limits oversight and transparency and heightens the risk of IFFs into and within Cuba (El País 2025; Luis 2024).

Lack of oversight, transparency and public accountability

According to international commentators, there is an absence of institutions with the independence and capacity to audit state entities or investigate high-level corruption in Cuba. Although the comptroller general’s office was reactivated under Raúl Castro, its operations reportedly remain opaque, and the office has failed to consistently issue public reports (BTI 2024:12).

Cuba’s efforts to investigate corruption are limited and often politicised. Although audits occasionally lead to the dismissal of public officials, these actions are rarely followed by transparent judicial proceedings (IACHR 2024). The lack of judicial independence is a central obstacle with the national assembly – under PCC control – overseeing judicial appointments and functioning without meaningful checks and balances (IACHR 2024). Furthermore, Cuba is one of the few countries in the region where public calls for judicial appointments are not published, and where there are no clear, publicly available criteria for disqualification or documentation of conflicts of interest (Alianza Regional por la Libre Expresión e Información 2024). Furthermore, lower court judges are often appointed without competitive exams, with recent law graduates sometimes placed directly into judicial roles as part of mandatory social service (Alianza Regional por la Libre Expresión e Información 2024). The consolidation of control over the judiciary serves as a critical enabler of systemic corruption and undermines any credible enforcement of anti-corruption efforts (Alianza Regional por la Libre Expresión e Información 2024).

Furthermore, in Cuba there is a generally a lack of access to public procurement data and financial disclosures from officials, as well as a weak freedom of information framework. The OCIndex (2023) reports that laws do not require asset declarations from public servants, and the media is neither free nor independent to investigate corruption. Civil oversight is virtually absent, and international organisations are barred from conducting independent human rights or corruption assessments inside the country. The state’s monopoly on information and its repression of transparency efforts further exacerbates the problem (Freedom House 2025).

Extent of corruption in Cuba

The extent of corruption in Cuba can be difficult to estimate due to the lack of dedicated, comprehensive studies, as well as the aforementioned lack of available data. However, various international assessments and indices, as well as isolated cases, give insights into the prevalent forms of corruption the country faces.

International assessments and indicators

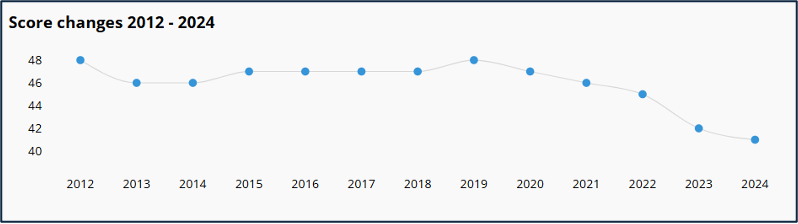

In Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 2024, Cuba scored 41 out of 100, ranking 82 out of 180 countries. This marks a steady deterioration from a score of 46 in 2021, a five-point decline over just three years, signalling increased public-sector corruption perceptions and a lack of transparency in key areas of governance (Transparency International 2025).

Figure 1: Cuba’s CPI score changes (2012-2024)

Source: Transparency International 2025

The World Bank’sWorldwide Governance Indicatorsreport that Cuba’s control of corruption percentile was approximately 52% in 2023. This places the country around the global median, implying a moderate level of corruption control. While this may suggest average performance in global terms, the World Bank (2024) highlighted in Cuba there is an absence of robust anti-corruption mechanisms compared to regional benchmarks.

TheBTI 2024 Cuba Country Reportprovides a detailed assessment of Cuba’s governance standards. The report notes that while some audits have been carried out by the comptroller general’s office, they lack transparency and are not applied to the powerful, military-run conglomerate GAESA. It gave Cuba a score of 4/10 for the prosecution of abuse of office, finding public dismissals for corruption rarely lead to judicial consequences, raising concerns over selective enforcement and political motivations behind prosecutions (BTI 2024).

Petty corruption cases

In Cuba, corruption at both petty and grand levels reportedly thrives in conditions of weak accountability, limited transparency and discretionary state power (CiberCuba 2024d). Evidence indicates that petty corruption is pervasive (Bak 2019). Citizens frequently encounter bribes for basic services, medical supplies, housing permits and access to goods distributed through state-run networks (Bak 2019).

For example, in May 2025, intermediaries in Havana were reportedly charging up to €500 for appointments to apply for Spanish nationality under the Law of Democratic Memory. These appointments, which should be freely accessible, were being commodified due to high demand and limited availability (14ymedio 2025). Other recent reports of bribes being demanded include in the customs sector (Periódico Cubano 2025b). Bak (2019) describes how bribes may be demanded in healthcare institutions in exchange for quality services.

Grand corruption cases

Grand corruption risks, while less visible, are also present in Cuba, particularly in sectors involving high-value state assets such as procurement, trade and remittance channels.

For example, in May 2024, the former director of the municipal commerce company in Sancti Spíritus, was sentenced to eight years in prison for authorising the irregular purchase of 42,000 units of near-expiry date soft drinks from a private supplier. Despite prior warnings about the transaction, the accused falsified documentation to conceal the irregularities, causing an economic loss exceeding 3.2 million Cuban pesos when the unsold stock expired (CiberCuba 2024c). A month later, authorities in Guantánamo dismantled a major corruption network responsible for embezzling more than 7 million pesos’ worth of goods intended for a municipal gastronomy company. The scheme involved fraudulent invoices and reconciliation procedures, ultimately leading to the company’s financial collapse and the dismissal of its entire workforce (CiberCuba 2024d).

In 2025, the government reported it had uncovered a similar corruption scheme at the Havana Liquefied Gas Company in whichexecutives of the Cuban Petroleum Union (CUPET) were reportedly embezzling funds and facilitating the diversion of gas resources (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre 2025).

Cuba’s international medical cooperation programmes constitute one of the country’s most significant sources of service export revenues (ONEI 2024). While official narratives have long emphasised the humanitarian goals of Cuban medical missions abroad, independent investigations and academic studies have raised concerns about transparency, data manipulation and the misuse of resources.

For example, the Cuban Observatory of Audit and Social Control (OCAC) alleged that GAESA was complicit in a scheme to embezzle vast sums from the collective salaries of doctors taking part in these missions between 2009 and 2022 (Diaz 2023). In addition, numerous Cuban doctors who defected from the programme have reported systemic issues, including the manipulation of patient records, misappropriation of medical supplies and coercion to participate in political activities (CONNECTAS 2021).

There is also evidence of international grand corruption schemes affecting Cuba, such as with the construction of the Mariel Port and the Special Economic Development Zone (ZEDM), Cuba’s flagship infrastructure project launched in 2014. The port, built with over US$860 million in loans from Brazil’s BNDES-Brazilian Development Bank, was awarded to Odebrecht, the Brazilian firm later convicted of orchestrating a massive regional bribery network. According to Brazil’s audit court, US$831 million was transferred directly to Odebrecht’s subsidiary without public bidding taking place(CONNECTAS 2019).Documents uncovered by investigative journalists relating to Drousys - Odebrecht’s clandestine accounting system for bribe payments – pointed to the existence of US$8.44 million in unexplained transactions linked to Cuba. Nevertheless, no Cuban officials were formally implicated in the Odebrecht scandal (Miami Herald 2019).

Corruption and illicit financial flows (IFFs) in Cuba

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) refer to cross-border movements of money that are illegal in origin, transfer or use. They may arise from criminal activities such as corruption, money laundering, drug trafficking and arms trafficking, but also from the unlawful transfer of legally earned funds from, for example, tax evasion or regulatory avoidance (Musselli and Bürgi Bonanomi 2020).

Although Cuba has at times been perceived as a potential destination for IFFs, particularly following its designation as a state sponsor of terrorism by the US Department of State (US Department 2021), such classifications may often be overstated. For example, the FBI has separately described Cuba as ‘an unreliable shelter for illicit funds’, citing cases in which Cuban authorities have prosecuted financial crimes and confiscated related assets (FBI 2019). According to the FBI, Cuba’s opaque institutions and discretionary enforcement make it an unpredictable environment for all parties involved (FBI 2019).

Furthermore, Cuba’s exclusion from the global financial system, combined with its limited integration into international banking networks, has traditionally made it a comparatively unattractive destination for financial crime (OCIndex 2023). This relative isolation may function as a deterrent to certain illicit activities, although it also limits external oversight and cooperation mechanisms.

Despite these facts, Cuba may serve as a conduit or temporary host for illicit financial flows, due to several factors including its authoritarian political system, prolonged US sanctions, restricted access to the global financial system and pervasive state control of the economy (Global Financial Integrity 2021:34). These elements, combined with chronic scarcity, foster informal markets and non-transparent financial practices that can facilitate both domestic corruption and cross-border illicit flows (OCIndex 2023:4).

IFFs cases

While Cuba has not traditionally been seen as a central hub for transnational financial crime, recent cases reveal growing exposure to IFFs connected to the island. These incidents, ranging from large-scale criminal networks to smaller operations involving individuals, underscore vulnerabilities within Cuba’s financial and regulatory systems, particularly in relation to transparency, institutional independence and international cooperation.

Russian mafia and photovoltaic energy projects

In early 2025, Spanish authorities, in collaboration with EUROPOL, dismantled a major money laundering network led by the Russian mafia. A notable element of this transnational scheme was its plan to funnel illicit proceeds into Cuba by investing in photovoltaic energy projects. The organisation reportedly aimed to supply renewable energy in exchange for access to strategic minerals (CubaHeadlines 2025; BBC 2025). Investigators revealed that the criminal network had initiated negotiations with Cuban government officials to facilitate these ventures, raising concerns over potential collusion. The case has triggered alarms regarding Cuba’s possible emergence as a jurisdiction of interest for offshore criminal funds, particularly in dealings with politically allied countries (CubaHeadlines 2025).

Undeclared cash seizures in Panama

In January 2025, Panamanian customs authorities intercepted a Cuban traveller arriving from Havana at Panama Pacific International Airport. The traveller was found carrying US$25,000 in undeclared cash concealed within a book, well above Panama's legal declaration threshold of US$10,000. This was the third such case that month involving Cuban nationals, pointing to a broader pattern of outbound currency smuggling and insufficient exit controls on the Cuban side (Periódico Cubano 2025c).

Operation ‘Mayabeque’

In early 2025, Interpol and Panamanian law enforcement arrested a Cuban national as part of a US$600,000 bank fraud and money laundering operation. The scheme, dubbed Operation Mayabeque, used sophisticated cross-border laundering techniques to obscure the origin of illicit funds. The individual was made subject to an extradition request from the United States (CiberCuba 2025b).

Miami-Dade case

Between 2022 and 2024, a Venezuelan national with documented ties to Cuba allegedly orchestrated a laundering scheme that moved over US$3.3 million through a network of Panamanian shell companies, US bank transactions and foreign accounts in Spain (BlanqueodeCapitales.com 2024). During a law enforcement raid on the suspect’s residence in Miami-Dade, authorities seized large quantities of cash in multiple currencies, including Cuban pesos, highlighting the financial trail linked to Cuba (Criminal Justice Online System 2024). US federal authorities prosecuted the case and of 2025, it remains ongoing and can be consulted through the Miami-Dade County court system.

Panama papers

The Panama Papers leak (ICIJ Database) exposed how high-ranking members of the PCC and their associates engaged Swiss intermediaries to establish offshore companies in jurisdictions such as Panama, the Bahamas and the British Virgin Islands (Miami Herald 2016; Martí Noticias 2016). These mechanisms served to conceal state business activities, divert funds abroad and shield personal wealth from scrutiny.

According to the Miami Herald (2016), at least 25 such offshore companies were connected to Cuba’s government or military sectors, with some dating back to the early 1990s. These entities were often associated with commercial operations, logistics and foreign trade managed by state-linked enterprises. According to the publicly available information at OpenCorporates website, one such firm, Corporación Cimex SA, was registered in Panama and functioned as the holding company for multiple Cuban state-owned entities, including Fincimex, which operated as an intermediary for Cuban exports and U.S. dollar transactions.

These structures allowed for the layering of financial operations, creating barriers to tracking funds and limiting external oversight. In several cases, the companies’ beneficial owners were obscured through nominee directors and trust arrangements (CONNECTAS 2020). According to FinGuru (2025), these practices mirror typical money laundering techniques and raise concerns over the circumvention of sanctions, illicit enrichment and the offshoring of national resources.

Caribbean transfers (2005–2011)

A Cuba-licenced remittance company was used to launder over US$230 million in proceeds from a US Medicare fraud scheme. The operation depended heavily on bulk cash movements, largely drawn from diaspora remittances, that were extremely difficult to monitor. US authorities described the case as an unprecedented money laundering scheme that exploited the remittance ecosystem and offshore shell companies to channel illicit profits into Cuba (Miami Herald 2015; Diario Las Américas 2017).

Anti-corruption policy & legal framework

The following section outlines the legal framework and oversight institutions currently in place in the Republic of Cuba, which shape the country’s approach to countering corruption and illicit financial flows.

In recent years under the new leadership, the government has been more outspoken about corruption, calling for the adoption of a zero-tolerance approach (Sánchez 2025). In March 2024, President Miguel Díaz-Canel launched a renewed anti-corruption campaign marked by high-profile dismissals and investigations of public officials. In the most prominent case to date, the former economy minister Alejandro Gil was removed and placed under investigation for ‘grave errors’ in the performance of his duties (Granma 2024; Reuters 2024; Swissinfo 2024a). Furthermore, Díaz-Canel replaced additional ministers and several provincial officials amid corruption allegations as part of this drive (Miami Herald 2024). In March 2025, the Ministry of the Interior reported investigations against over 125 state officials on suspicion of corruption and irregularities that had been undertaken in the previous eight months (Sánchez 2025). Nevertheless, commentators have noted that the government has generally been reluctant to disclose details about the allegations and charges made against parties accused of corruption, such as in the Gil case (Sánchez 2025; Associated Press 2024).

Cuba’s international commitments to anti-corruption and AML standards

Cuba is formally committed to several key international frameworks aimed at countering corruption and illicit financial flows. It is a state party to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), having ratified the treaty in 2007. Cuba also ratified the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) the same year, following its initial signature in 2000. At the regional level, Cuba is a member of the Financial Action Task Force of Latin America (GAFILAT) and underwent its most recent mutual evaluation in 2015, assessing its compliance with AML/CFT (anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism) standards.

In addition, Cuba’s financial intelligence unit (Dirección General de Investigación de Operaciones Financieras) has been a member of the Egmont Group, the international network of financial intelligence units, since the mid-2010s. This membership facilitates cross-border cooperation and information exchange. Notably, Cuba was removed from the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) monitoring grey list in 2014, following significant reforms that addressed prior AML/CFT deficiencies (Granma 2014). As of June 2025, Cuba is not classified as an AML-deficient jurisdiction by FATF.

Cuba’s domestic legal framework on anti-corruption and anti-money laundering

Cuba’s domestic legal framework includes a set of laws and regulations aimed at addressing corruption, economic crimes and money laundering. The Cuban penal code is the primary legal instrument for prosecuting corruption-related offences. It criminalises acts such as bribery, abuse of power, influence peddling, embezzlement and misappropriation of public funds by public officials. A major revision to the penal code came into force in 2022, introducing harsher penalties and expanding the scope of offences to cover modern economic crimes and illicit financial conduct (INCSR 2024:115). Notably, Article 324 of the new penal code explicitly criminalises money laundering, including provisions for aggravated sentencing when linked to public corruption or organised crime.

In parallel to criminal provisions, Cuba has developed a comprehensive regulatory framework focused on AML and CFT. The cornerstone of this system is Decree-Law No. 317 of 2013 (published in 2014), which requires financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) – such as real estate agents, notaries and currency exchange houses – to conduct customer due diligence, maintain transaction records and report suspicious activities to the national financial intelligence unit (INCSR 2024:114). This law is supported by Decree No. 322 of 2013, which outlines procedures for identity verification, risk monitoring and reporting protocols. Additionally, Resolution 51/2013 of the central bank of Cuba provides technical guidance for the implementation of AML/CFT measures within regulated entities.

This framework has continued to evolve. Between 2021 and 2023, new central bank resolutions were issued to address emerging risks, including those posed by virtual assets, digital payments and financial technologies. Notably, Resolution 215/2021provided the first legal framework for the use of cryptocurrencies, defining virtual assets and outlining the conditions under which individuals and entities may engage with them. In 2023, the central bank also introduced new policies aimed at reducing cash use and expanding digital payment systems across the economy (Caribbean Council 2023). Current AML regulations also require financial entities to identify the beneficial owner of accounts or transactions. However, the broader implementation of beneficial ownership registries, common in many international jurisdictions, remains limited in Cuba due to the restricted scope of private ownership and the dominance of state-controlled enterprises (GAFILAT 2015:178).

While Cuba’s legal architecture is formally aligned with international AML/CFT norms, challenges reportedly remain in enforcement, transparency and institutional independence, particularly in relation to high-level corruption cases and the operations of state-linked economic actors (INCSR 2024:13).

Key institutions in Cuba’s anti-money laundering and anti-corruption framework

Oversight and audit

General Comptroller’s Office (Contraloría General de la República): established in 2009, the general comptroller’s office serves as Cuba’s supreme audit authority, tasked with overseeing the management of public funds and curbing administrative corruption. It conducts audits of state entities and has led anti-corruption initiatives in sectors such as food procurement, civil aviation and tourism. However, it does not oversee GAESA. Former comptroller Gladys Bejerano stated that GAESA is not under the comptroller’s supervision due to its ‘superior discipline and organisation’ developed over decades of business experience (EFE 2024). The functions and scope of the comptroller’s office are defined by Law 158/2022. According to the law, certain entities such as GAESA are granted the mandate to carry out internal oversight instead of being subject to the general comptroller’s office’s supervision.

Financial regulation and intelligence

Central Bank of Cuba (Banco Central de Cuba): the central bank is the primary regulatory authority for Cuba’s financial system, responsible for issuing AML/CFT regulations and ensuring compliance among financial institutions. It plays a central role in implementing policies to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing.

General Directorate for the Investigation of Financial Operations (Dirección General de Investigación de Operaciones Financieras - DGIOF): created by Decree 322 and operating under the central bank, DGIOF functions as Cuba’s financial intelligence unit. It is responsible for receiving, analysing and disseminating information related to suspicious financial activities. DGIOF coordinates with law enforcement agencies to investigate and prevent financial crimes and is a member of the Egmont Group, facilitating international cooperation in AML/CFT efforts.

Ministry of Finance and Prices (Ministerio de Finanzas y Precios): while not a frontline enforcement agency, this ministry plays a supporting role in aligning financial regulation with fiscal and AML/CFT policies. It collaborates closely with the central bank and other regulatory bodies to shape and update Cuba’s economic and financial governance structures.

Investigation and prosecution

Ministry of the Interior (Ministerio del Interior - MININT): MININT oversees national law enforcement agencies and is responsible for maintaining internal security in accordance with Resolution number 2 issued in 2001. It has specialised units dedicated to investigating economic crimes, including money laundering and corruption. These units work closely with other government bodies to enforce AML/CFT laws and regulations (Granma 2019).

Office of the Attorney General (Fiscalía General de la República): the attorney general’s office leads the prosecution of criminal cases, including those related to money laundering and corruption. It works in conjunction with investigative agencies to bring cases to court and ensure legal compliance according to articles 3, 6 and 12 of the Law 160. The office also contributes to the development of legal frameworks and policies aimed at strengthening Cuba’s anti-corruption and AML/CFT measures.

Ministry of Justice (Ministerio de Justicia): according to the official description of the ministry of justice’s mandates and functions, the institution provides legal oversight and is responsible for the development and implementation of legislation related to financial crime. It works in tandem with the judiciary and prosecutorial bodies to ensure legal consistency in AML/CFT proceedings and reforms.

Auxiliary enforcement and monitoring bodies

National Office of Tax Administration (Oficina Nacional de Administración Tributaria – ONAT): ONAT is responsible for tax collection and enforcement. It contributes to AML efforts by monitoring financial behaviour, detecting tax evasion schemes and sharing intelligence with financial and prosecutorial authorities when such activity overlaps with money laundering.

Customs General of the Republic (Aduana General de la República): Cuba’s customs authority plays a preventive role in AML/CFT by enforcing cross-border controls on cash and monetary instruments. It is mandated to detect undeclared funds, smuggling and currency trafficking, especially through air and maritime points of entry. Its functions are grounded in article 15 and other clauses of the Decree-Law 162/1996.

Other stakeholders involved in AML and anti-corruption in Cuba

In addition to the public stakeholders previously referenced, other relevant actors also participate, to varying degrees, in Cuba’s anti-corruption and AML/CFT landscape. These stakeholders, while often operating under state influence or with limited autonomy, contribute to shaping the public discourse and institutional culture around integrity, transparency and financial accountability.

Civil society organisations

Cuba’s civil society is largely aligned with the state. One notable actor is the National Association of Economists and Accountants of Cuba (ANEC), which provides training in financial auditing and promotes internal control systems across public and private sectors. Similarly, the National Union of Cuban Jurists (UNJC) contributes to legal education campaigns and supports the development of anti-corruption legislation. However, both organisations operate within the parameters of state control and lack the independence required to carry out autonomous oversight or critical monitoring (BTI 2024:29).

Mass organisations such as the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDR), the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) and the Cuban Workers’ Central (CTC) are expected to function as community level watchdogs, reporting misconduct in neighbourhoods and workplaces. However, according to BTI (2024:29), their primary role in practice revolves around political mobilisation and social control under the supervision of the Cuban Communist Party rather than meaningful oversight or accountability.

In Cuba, other civic actors and NGOs may be prevented by the state from legally registering their operations. As a result, watchdog functions are confined to informal or diaspora-supported networks, with limited reach inside the island (Freedom House 2025). Moreover, the media ecosystem remains under state control. While digital outlets and social media have become spaces for limited expression, they are monitored and occasionally blocked, and their contributors may face intimidation or forced exile (Freedom House 2025; BTI 2024:10).

Citizen complaint mechanisms

Cuban citizens have access to formal complaint channels through local delegate assemblies (planteamientos) or institutional feedback mechanisms (Guanche 2014). Although these mechanisms formally exist, there is little practical evidence that concerns raised through them lead to investigations or corrective measures. Their impact remains limited and largely dependent on the political will of local authorities or institutions (Guanche 2014).

Independent media and investigative journalism

Digital news platforms such as 14ymedio, El Toque, Cubanet and CiberCuba have emerged as critical voices in exposing corruption, patronage networks and illicit economic activity. Operating largely from exile or semi-clandestinely inside Cuba, these outlets lack legal recognition and face systematic censorship. According to Reporters Without Borders (2025), Cuba remains the lowest-ranked country in Latin America for press freedom, severely restricting the capacity for independent investigative journalism.

Despite serious risks, including surveillance, harassment and arbitrary detention, some freelance journalists and whistleblowers continue to document cases of local corruption or share anonymous testimonies. These efforts, while fragmented and often informal, contribute to the increased visibility of misconduct and serve as a counterbalance to the state-dominated media narrative (Human Right Watch 2025; Amnesty International 2025:175; IWPR 2013).