Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption risks and anti-corruption measures in secondary and tertiary education across the Central Asia region.

Caveat

The scope of this Helpdesk Answer is wide, covering various aspects of corruption and anti-corruption in the education sector across the five countries in Central Asia. Therefore, the literature review and treatment of these different topics should be understood as non-exhaustive in nature and more as an entry point. The reader is invited to consult the listed sources for more detail.

This Helpdesk Answer references government and media sources. Some of these sources may contain bias and should be treated with caution given the currently low levels of press freedom and the authoritarian nature of governments in some Central Asian countries.

Values in different currencies of Central Asian countries are maintained in this Helpdesk Answer but also converted into US dollars for illustrative purposes. These were calculated at mid-market exchange rates at various points over July and August 2025 which may no longer be up to date, so these estimates should be treated as indicative only.

Background

This Helpdesk Answer explores the nature and prevalence of corruption and anti‑corruption safeguards in the education systems in the Central Asia region. It limits its scope to the five countries typically considered to be part of the region826c14101967 – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – and focuses on secondary and tertiary education, instead of primary level.

The existence of corruption in the education systems of Central Asian countries has been in part shaped by common legacies deriving from the former Soviet Union.c9af99007dc4 Huisman et al. (2018: 16) describe how the admissions process for tertiary education during the Soviet period was restrictive and applicants could take admission exams at only one institution at a time, which created opportunities for corruption and restricted equitable access. Driven by the limited number of places, officials would reportedly sometimes influence the process to favour certain applicants (Алиханов 2021: 6-7). While most Central Asian countries have since reformed and broadened their admission processes, Turkmenistan’s reportedly remains restrictive (Huisman et al. 2018: 16).

Describing Kyrgyzstan’s secondary education system, Akmatjanova et al. (2014: 5-6) describe how, during the Soviet era, most education costs were subsidised by centralised funding. Following the dissolution of the union, parents were increasingly expected to cover some costs (such as textbooks and school equipment) through ostensibly voluntary contributions towards informal school support funds, which Akmatjanova et al. (2014: 6) argue are inherently vulnerable to abuse and corruption.

However, the current funding and governance models across the five countries are more heterogenous. Eckel (2021: 5) emphasises that universities in the “former Soviet states have evolved in different ways and at different paces” since the union’s dissolution, pointing out that some remain under strong government influence in terms of their agenda while others have more autonomy. Similarly, they are subject to different funding models. For example, in Tajikistan, tertiary education institutions are mostly funded by state budgets, whereas in Uzbekistan they are largely self-funded through tuition fees (UNESCO Office in Almaty 2021: 5).

Furthermore,Ambasz et al. (2023: 7) state that all Central Asian countries have generally expanded participation rates in higher education institutions. As part of this, a large number of private tertiary level institutions were established in Central Asia during the transition period (Ambasz et al. 2023: 7).On the basis of interviews carried out with key stakeholders working across public and private universities, they found that most continue to report issues such as non-transparent funding processes and excessive bureaucracy (Ambasz et al. 2023: 20).

Impacts of corruption in the education sector

Hallak and Poisson (2002: 17) provide the following definition of corruption in education: “the systematic use of public office for private benefit whose impact is significant on access, quality or equity in education”. Their definition stresses the multidimensional impacts that corruption in the sector can trigger.

In the same vein, Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017) describe how corruption “undermines the quality and availability of education services by distorting access to education”. They give the example that when resources allocated for education needs are embezzled, this can trigger budget cuts and result in fewer teachers and larger class sizes. This restricts access and reduces quality of learning. Furthermore, if corruption undermines the academic integrity of tertiary institutions, it can contribute to a “brain drain” and lead prospective skilled professionals to emigrate, while underqualified graduates occupy important positions in the economy and public administration (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017).

While there appear to be few attempts to quantify the impacts or costs of corruption in education across the region, the negative consequences of corruption generally are well recognised within the literature.

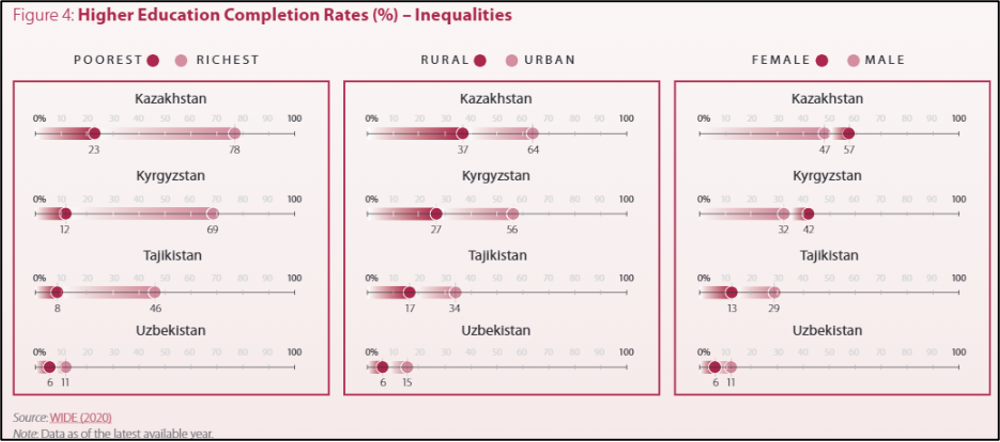

In terms of equitable access, the UNESCO Office in Almaty (2021) has compared higher education completion rates across four of the countries in the region (see Figure 1). This suggests Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have overall lower rates and more persistent inequality, especially based on socio-economic status and the urban/rural divide.

Figure 1: Discrepancies in higher education completion rates across four Central Asian countries

For this UNESCO Office in Almaty report, data from Turkmenistan was not included. Source: UNESCO Office in Almaty 2021

Corruption can undermine efforts to improve access. As BTI (2024) notes in the case of Tajikistan that, while in theory education opportunities are equally open to all, in practice access to higher education is limited by the frequent demands to pay illicit fees to be admitted or pass examinations. According to Asanalieva and Asanbaeva (2022: 46), in some rural regions of Kyrgyzstan, women and girls already have limited access to full secondary and higher education. Such trends can be exacerbated by forms of corruption that limit the availability of resources and may lead families to choose to prioritise the education of boys. This phenomenon is likely to exist in other Central Asian countries, such as, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan where available statistics indicate that girls are already disproportionally less likely to complete higher education (see Figure 1).

Corruption also has an impact on the quality of education across the region, which in turn undermines economic development and other national aspirations. According to the UNESCO Office in Almaty (2021), tertiary education is seen by governments as crucial for the development of Central Asian economies, which aim to diversify away from a reliance on natural resources. Similarly, Ambasz et al. (2023: 18) state there is a general recognition that education is important to underpin economic growth, but there are shortages of skilled workers. They explain the role corruption plays in this context, arguing that it hinders the modernisation of university management systems and institutional performance (Ambasz et al. 2023: 20).Further, Central Asian universities generally perform poorly on global research efficiency indicators, indicating that their full potential for promoting innovation in the national economy is not realised (Ambasz et al. 2023: 19).

A World Bank report (2014) on Tajikistan explains that if a student obtains an undeserved qualification through corruption, it has a negative impact on workplace efficiency, given that actual “skills do not match qualifications”. Similarly, Trilling (2011) cites a local expert who notes that corruption in tertiary education in Tajikistan leads to a lack of qualified experts in almost every field. According to Grzegorczyk (2025), higher quality schooling in the region can yield manifold development impacts such as reducing unemployment and curbing youth migration to neighbouring countries such as Russia and enhance the mobility of marginalised groups, such as girls living in areas where conservative social norms persist.

Central Asian governments generally recognise the transformative potential of education, as demonstrated by relatively high investment levels in the sector. With the exception of Turkmenistan, all countries spend more on education as a percentage of total GDP than the Europe & Central Asia average (see Table 1).2995094530a3

Table 1: comparison of government expenditure on education (% of GDP) across the Central Asian region

|

Country |

Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP) |

Most recent year data is available |

|

Kazakhstan |

4.5% |

2022 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

6.8% |

2023 |

|

Tajikistan |

5.8% |

2023 |

|

Turkmenistan |

2.9% |

2023 |

|

Uzbekistan |

5.5% |

2023 |

|

Europe & Central Asia average |

4.5% |

2022 |

Source: World Bank n.d.

Corruption amounts to a waste or loss of the resources allocated to education and thus undermines investment in the sector. Furthermore, corruption reduces domestic revenue mobilisation, reducing the total quantity of funds available to a government to spend on education. Effective measures to curb corruption have the potential, therefore, to ensure that a greater proportion of funds allocated to education actually materialise and are used for their intended purpose. In fact, anti-corruption efforts can even result in more funding becoming available for investment in sectors like healthcare and education. For example, the Kazakh Ministry of Education claimed it had constructed 43 schools and created over 50,000 school places in 2023 using funds confiscated from the country’s general crackdown on public officials for corruption offences (CentralAsia.news 2024).

Extent and forms of corruption

This section gives an overview of different sources and evidence attesting to the manifestation of corruption in secondary and higher education in Central Asia.

Data availability

Conducting research on corruption in general in Central Asia is difficult due to the political climate and autocratic nature of some of the regimes. Rickleton (2022) describes the low levels of press freedom in the region, where reporting on corruption implicating national elites is often viewed as crossing a “red line”. In Freedom House’s 2025 Freedom in the World report, which measures the national level of civil liberties and political rights, all five Central Asian countries were classified as “not free” (Freedom House 2025; The Times of Central Asia 2025).

Therefore, academic literature on corruption in the sector in the region remains underdeveloped, although there has been increasing attention in recent years. Jonbekova (2018: 1) states that in Central Asian universities the general topic of corruption has often been regarded as politically sensitive, impeding research on it. Another expert concluded that “[s]cientific research on corruption in Central Asian higher education [was] limited, but existing studies and testimonies indicate that countries in the area have had problems with principals, professors and other staff accepting bribes in exchange for admission and higher grades” (Lund University 2020).

Indeed, national stakeholders may withhold data from the public. For example, the OECD (2020: 354) relates how its monitoring team was informed by the Kazakh government that a full-scale study on corruption risks in the education sector had been conducted, but the study was not shared with them nor made public. The OECD (2020: 354) criticised the “secretive approach” taken by the Kazakh education authorities in disclosing data on corruption.

However, government stakeholders in the Central Asian countries have, to some extent, acknowledged the existence of corruption in their education systems. This has taken the form of public announcements by anti-corruption and education authorities detailing uncovered corruption incidents or schemes in the sector, and some governments also collect and report data, albeit often at a higher, aggregate level. For example, in 2023, the Tajikistan anti-corruption authorities identified a total of 2,155 cases of corruption and other forms of economic crime occurring within state and affiliated bodies, leading to losses of 247 million somonis (almost US$27 million). Within this, the single body which incurred the greatest loss was the Ministry of Education, equating to more than 30 million somonis (approximately US$3.1 million) (AsiaPlus 2023). In another survey of 1,200 students, parents and teachers, coordinated under the supervision of Tajik authorities, 40% of respondents stated they had observed corruption in an educational institution in their region (AsiaPlus 2024).

Forms of corruption

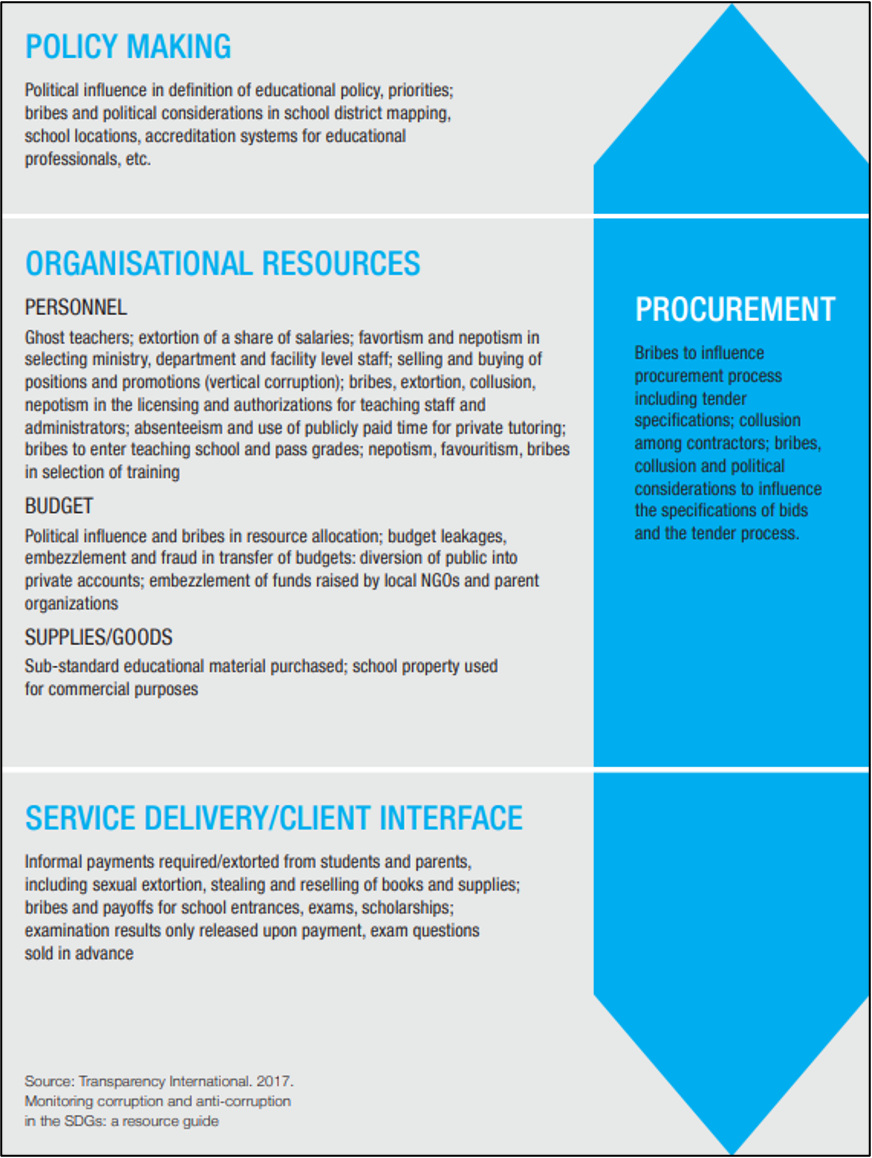

In terms of forms of corruption, Poisson (2010: 1) describes how both grand, large-scale corruption as well as petty corruption can occur in the sector. Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:3) describe how such manifestations of corruption can occur at virtually all stages of the education delivery chain, from decision-making on education policies and the management of organisational resources (including personnel, supplies and budget allocated for educational purposes) to the point of interacting with and delivering education services to users, such as students and their guardians (see Figure 2). These three stages attest to the fact that not only frontline actors (such as teachers and lecturers) engage in corruption but also civil servants within state education bodies and even high-ranking political figures. For example, in Kazakhstan, high-ranking officials and/or their relatives reportedly have ownership stakes in the majority of tertiary educational institutions, creating stark conflict of interest risks; for example, a former education minister held ownership shares in a private university while his daughter acted as the head of Kazakhstan’s accreditation agency (Radio Azattyk 2021).

Nevertheless, given the aforementioned sensitivity and data availability issues, it can be difficult to locate concrete evidence of corruption schemes in the education policymaking stage that implicates high-level officials across Central Asian countries. For example,Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, the former president of Turkmenistan, detained a former deputy minister of education for large-scale corruption, but few details were published about the accusations against him (Хроника Туркменистана 2020); given that Berdimuhamedow is widely considered to have led an authoritarian regime, there is also a possibility the accusations were politically motivated. Therefore, while most of the evidence presented below pertains to the organisational resources and service delivery stages, it should be acknowledged that acute corruption risks also likely exist at higher stages of the education service delivery chain in some countries within the region.

Figure 2: Overview of forms of corruption across the education service delivery chain

Source: Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017:4

The remainder of this section is divided into subsections covering a selection of forms of corruption which – from a review of the literature – appear to constitute key risks across the region. Nevertheless, the selection of forms and the country examples given for each of them should not be considered exhaustive, but rather illustrative in nature.

Bribery

Bribery in the education sector can occur in multiple ways, often overlapping with other forms of corruption. For example, Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:6) describe how, at the service delivery level, corruption often takes the form of bribery and extortion, where parents and students are asked to make payments to access education services that are supposed to be free of charge. Across the Central Asian countries, numerous media reports and studies indicate that bribery constitutes a key risk in the education sector as bribes are paid in return for a wide range of acts in ways that implicate multiple levels of the public administration.

The number of people who reported first or second-hand experience of paying a bribe in public education institutions ranged from between 13% and 45% of respondents to the 2016 Global Corruption Barometer, the most recent available cross-country data. The figures varied according to the level of education and country, with Tajikistan’s tertiary education institutions recording the highest rates of reported bribery as of 2016 (see Table 2).

Table 2: Global Corruption Barometer 2016: percentage of people who gave a positive response to the question “have you or another member of your household paid a bribe to any one of eight public services in the past 12 months?”*

|

Country |

Public education (primary or secondary) |

Public education (tertiary) |

|

Kazakhstan |

17% |

23% |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

13% |

23% |

|

Tajikistan |

26% |

45% |

|

Uzbekistan |

14% |

16% |

* Data is not available for Turkmenistan which did not participate in the Global Corruption Barometer 2016. Source: Transparency International 2016

High-level political actors can be complicit in bribery offences. In 2022, the former education minister Almaz Beishenaliev was charged with taking multiple bribes totalling US$110,000 in exchange for arranging foreign students’ admission to universities in Kyrgyzstan (Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 2022). In 2024, a court convicted Beishenaliev, handing down a fine of 1.5 million soms (approximately US$17,000) (24kg 2024).

It may occur more directly at the level of schools and universities. In one case, heads of two Kyrgyz universities reportedly demanded students pay up to US$900 to receive approval to study abroad in Chinese institutions (Dzhumashova 2023). In 2023, a school director in Bishkek was arrested for accepting a bribe of 5,000 soms (US$57) to approve the transfer of a child to her school (Daryo 2023a). Bussen (2017) concluded that bribery in secondary schools in Kyrgyzstan occurred in part as a response to teachers’ low salaries but is also enabled by the general lack of oversight of teachers.

The offering of bribes by (prospective) students may be motivated as a cost-saving measure. Trilling (2011) interviewed a student who applied to a university in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. The student reported having paid a US$100 bribe to a university dean who facilitated his entrance to the university on a government funded scholarship, which allowed him to avoid paying the tuition fee of US$600 per year. Trilling (2011) states that the size of the bribe paid varied according to the perceived prestige of the programme, with higher values expected for law or economics studies.

In other cases, bribery occurs at the administrative level in a manner that might not directly affect service users. For example, in Kazakhstan, a school director gave a bribe to officials from an educational services licensing department to obtain a licence for her school; the director and officials were later both convicted (Шемратов 2025).

Bribes may also facilitate wider impunity in the sector. In 2020 in Turkmenistan, the former deputy education minister Merdan Govshudov was convicted of accepting bribes from the Ashgabat head of the education department to protect the corrupt practices of the latter from being exposed (Acca 2020b). In Ala-Buka, Kyrgyzstan, the prosecutor general’s office launched an investigation into the local education department, which was suspected of extorting and collecting bribes from school directors in return for issuing them with positive inspection reports (Kabar 2024b).

The UNODC (n.d.)distinguishes bribery from extortion, saying that under the former, the party which receives the bribe typically performs an act in favour of the party that gives the bribe. In contrast, under the latter, the receiver threatens to cause harm to the extorted party unless they provide a payment.

In many cases across the region, what looks like bribery may actually constitute responses to extortion. For example, in one school in Turkmenistan, there were reports of teachers threatening to give students a poor grade for their exams if they refused to give them a bribe (Azatlyk Radiosy 2023a).

In another report from Mary, Turkmenistan, some parents complained about teachers demanding payments and other favours from students ahead of graduation exams, making them fear repercussions if they did not comply (Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 2023). However, some parents also noted that bribery can also occur on the initiative of wealthy parents who offer gifts and cash to influence the grades awarded to their children (Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 2023).

In a similar vein, in a survey conducted by the Uzbek anti-corruption agency between 2023 and 2024 at 16 universities, 76.7% of respondents (including students, lecturers and administration employees) expressed their belief that the leading cause of bribery in universities was the students in comparison to 34.3% who believed it was the lecturers (UZ-Daily 2024).

Bribes can also be distinguished from “informal fees” which may appear to be legitimate, for instance, to fund shortfalls in educational materials that are nominally covered by state budgets, but in practice the collected funds can be used in an opaque manner (OSF 2010). A 2014 study by TI Kyrgyzstan found that state underfunding of schools was often compensated through payments by parents or guardians of children, for example, to purchase furniture and equipment for classrooms. However, it concluded that these payments had evolved from being “voluntary to involuntary” in nature, creating an expectation that parents and guardians make donations to avoid consequences such as their child being neglected (Akmatjanova et al. 2014: 5). In a survey of over 1,100 parents and guardians, over 80% of respondents based in urban areas stated a system of informal payments existed in their schools; however, this figure fell to 26% for respondents from rural areas (Akmatjanova et al. 2014: 7).

In Tajikistan, informal fees are also reportedly regularly collected for the purchase of classroom furniture, textbooks and for repairs (AsiaPlus 2024). In Turkmenistan, there were reports of students having to make payments for school renovations and to pay for teachers’ lunches (Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 2023). Sometimes, the connection of informal fees with private profits is evident. For example, in Turkmenistan, a report found that schools were making it mandatory for students to wear uniforms that only the school itself could sell, and they were doing so at inflated prices around 30% above the market price (Azatlyk Radiosy 2023b).

Embezzlement

Kirya (2019: 3) describes how embezzlement and diversion of budget funds results in a loss to the amount nominally allocated toeducation. Evidence of suspected embezzlement cases across Central Asia suggests again that actors at different levels of seniority within the sector can be complicit.

In Kyrgyzstan, the head of the provincial government’s finance ministry reportedly colluded with employees of educational facilities to embezzle up to US$1.1 million from the local budget (Acca 2020a). In a case from Tajikistan, two companies that received funds from the president’s reserve fund to purchase computers for schools delivered subquality products or in some cases, even “empty boxes”; the executives of both companies were charged with embezzling the funds and handed prison sentences of up to ten years (Ozodi 2015).

In Kazakhstan, an embezzlement scheme was uncovered in which the chief accountant of the Taldykorgan education department was suspected of colluding with officials from up to 25 schools to embezzle up to 4.5 billion tenge (approximately US$8.3 million) between 2020 and 2023 (Orda.kz 2023). In another case in Astana, school accountants were convicted for transferring 130 million tenge (approximately US$240,000) in salaries and bonuses to non-existent employees, which they then embezzled (Беймарал 2024).

In 2024, the Kazakh anti-corruption authorities conceded they had detected numerous incidents of leakages from the sector, attributing these to vulnerabilities in its public financial management system, such as a lack of automation and integration of accounting databases (Gov.kz 2024). The Kazakh anti-corruption authority explained that embezzlement schemes can also involve officials working in payroll management where, for example, salaries are credited to one employee’s account, but another person’s name appears on the payment order (Шашкина 2023).

Bid rigging

Public tenders issued by authorities in the education sector can be highly sought after given they often entail long-term, high-value contracts. This can include, for example, the construction and operation of school facilities and the provision of textbooks (Kirya 2019: 42). These lucrative opportunities can incentivise unscrupulous actors to engage in forms of fraud or “bid rigging” in which bidders collude with the people responsible for procurement. This can result in the non or low quality fulfilment of the stipulated terms of the contract.

The Kazakh anti-corruption agency stated that between 2016 and 2020, it recorded 77 corruption offences involving public procurement in the education sector, which was higher than other sectors such as health and agriculture (Junusbekova and Khamitov 2021: 414-5).

In Kyrgyzstan, the prosecutor general’s office opened an investigation against the chief public procurement specialist in the Bishkek department of education on suspicion of awarding 35 out of a possible 73 tenders to a company owned by an acquaintance. Under the bid rigging scheme, fake bids were made by a third party in order to inflate prices (Knews 2025).

In an older, but similar case, the prosecutor general investigated employees of both the Bishkek city authority and a company on suspicion of colluding to select a bid without the necessary documentation and inflating the cost for the construction of a school (Токтоназарова 2017).

In 2023, the Uzbek anti-corruption agency reported having identified cases of two procurement processes for vocational schools that were manipulated to favour certain bidders (Anti-corruption Agency of the Republic of Uzbekistan 2023a; 2023b). In another case from Uzbekistan, the national anti-corruption agency identified irregularities in the decision of a procurement commission to award a contract worth 403 million soms (approximately US$31,500) to repair the heating system of a vocational school. The anti-corruption agency concluded that the evaluation process had been compromised to favour the winning bidder (Alampir.uz 2024).

The Eurasia Foundation (2022) published claims made by an independent journalist regarding a potential case of procurement fraud in Uzbekistan. The journalist claimed that 300 state organisations, including universities and colleges, had purchased multiple copies of a book written by the president of Uzbekistan, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, at a cost of 7.8 million soms (approximately US$650) per book. The journalist interviewed a whistleblower who reported that universities were pressured to buy the book following an official letter from a high-level education ministry official, bypassing the procurement process to which other acquisitions of learning material are subject (Eurasia Foundation 2022).

Unfair recruitment

According to Kirya (2019: 12), recruitment and promotion decisions in the education sector may be based on favouritism, nepotism and bribery rather than the fulfilment of clear criteria. This can result, for example, in unqualified personnel assuming teaching positions and a skewed distribution of postings, creating pressure on other teachers (Kirya 2019: 12).

This form of corruption is pertinent to a wide range of roles across the sector. In Tajikistan, in the first six months of 2020, 41 cases of nepotism in public bodies were recorded, 18 of which occurred in the education sector (Зарифи 2020). In 2023, Kyrgyzstan’s President, Sadyr Japarov, highlighted the need to root out nepotism in government hiring and highlighted the education ministry as one of the entities prone to the malpractice (Daryo 2023b). Bekmurzaev (2023) describes how previously in Kyrgyzstan, regional and city education departments were given complete autonomy to appoint and dismiss principals, but this enabled corruption and was therefore replaced by a more competitive, merit-based process. Ambasz et al. (2023: 28) explain that, within Central Asian universities more generally, the appointment procedures for leadership roles within the administration tend to be highly centralised and politicised rather than meritocratic.

There may also be an overlap with bribery and extortion. For example, in some rural areas of Kazakhstan, payments are reportedly demanded of candidates to secure teachers’ and principals’ positions, with higher values expected for the latter (Acca 2021). Candidates reportedly often comply with these demands as these positions offer a relatively stable income; it is also common that a portion of the teacher’s salary is deducted to cover such payments (Acca 2021).

Private tutoring

Another phenomenon which can be linked to corruption is private tutoring, where teachers on the public payroll offer private tuition to paying pupils (Kirya 2019: 6). Kirya (2019: 6) explains this can reduce teachers’ level of engagement during their regular classes.

Extra-curricular private tutoring by publicly funded teachers might be legal in some contexts and even serve as a coping mechanism for low salaries, but it can give rise to conflicts of interest in certain situations. For example, in Kazakhstan, private tutoring in schools is legal and reportedly common. However, according to the OECD (2020: 351), the practice has led to teachers offering private classes to pupils from their own school and “underrat[ing] pupils’ performance thus artificially creating the need for extra private classes”. Hajar and Karakus (2025) surveyed over 950 teachers in Kazakhstan and found that almost 40% of them admitted engaging in fee-based private tutoring, including of the same students they regularly teach. The practice is also reportedly widespread in Uzbekistan, often as a way to compensate for salaries that are perceived to be low (Khimmataliyev and Eshbekova 2023).

Huisman et al. (2018: 215-6) note this practice extends to the tertiary level across the region, and some faculty staff secretly teach at multiple universities in response to low salaries, which creates constraints on their regular positions and affects quality.

Academic fraud

Camacho (2021: 6) points out that universities can engage in several activities that violate academic integrity, such as acting as so-called “degree mills” which hand out degrees to people who have not fulfilled academic requisites but who are willing to pay high fees. These activities again often have a significant overlap with bribery. In Kyrgyzstan, corruption can reportedly influence authorities’ decision to license educational institutions, and where tertiary institutions of a dubious nature are able to pay off licensing authorities to receive official accreditation (Kharizov 2022).

Such “fake diplomas” contribute to an underqualified workforce and undermine the standards of Central Asian institutions. In Kyrgyzstan, the State Committee for National Security (GKNB) announced it would investigate over 20 universities for producing fake diplomas after having identified cases where lawmakers, judges, teachers and police officers were suspected of being in possession of them (Imanaliyeva 2022). Similarly, in Sughd, Tajikistan, the public prosecutor announced it had identified 16 cases where people in teaching positions were suspected of holding fake university diplomas (Ozodi 2017). This indicates that academic fraud can create feedback loops and lead to lower quality in the wider sector.

Another overlap of corruption and academic fraud is when examination processes are compromised and students are awarded inflated grades. In Kazakhstan, a survey of over 20,000 people found that 23.8 % of respondents had encountered some form of corruption when they were taking exams (Inform.Kz 2022). In Nukus, Uzbekistan, authorities revealed having uncovered a corruption scheme orchestrated by the school deputy director at a vocational school who colluded with teachers to collect bribes from students in return for allowing them to take exams with mobile phones and neglecting supervision duties to help them pass professional certification exams (Zamin 2025).

Anti-corruption measures

This section provides a non-exhaustive overview of responses to corruption in secondary and higher education that have been recommended in the literature more widely. It then proceeds to draw illustrative examples from existing practices across the region. While the adoption of anti-corruption measures in select countries may signal increased political will to counter corruption in the sector, it should be caveated that few studies have been undertaken to assess the effectiveness of such measures in the education sector across Central Asia.

Sector-specific commitments

Within the anti-corruption field, there has been a shift to sector-specific approaches. Pyman and Heywood (2021) advocate for strategies tailored to a particular sector, such as education, to improve the likelihood that targeted public officials are receptive to and take ownership of the anti-corruption measures introduced.

In Central Asian countries, where sector-specific commitments on corruption and education exist, they mostly appear as references to the education sector in broader anti-corruption strategies and policies and, in some cases, the development of tailored action plans.

However, these are more extensive in some national contexts than others, and implementation is often unclear. Tajikistan’s anti-corruption strategy for 2013-2020 had an entire section on the education sector, which singled out the lack of regulations and inadequate oversight mechanisms as drivers of corruption. The section also included several actions to be undertaken, such as expert assessments of existing laws and improving the salaries of education sector employees to the extent possible given available resources (OECD 2017: 19). Tajikistan’s more recent strategy for 2021-2030acknowledges an observed increase in the level of corruption in the education sector, particularly in relation to embezzlement. In response, it commits to certain measures, such as enhanced collaboration between the education ministry and the national public procurement agency (Constitutional Court of the Republic of Tajikistan 2021).

In contrast, the 2015-2025 Kazakh anti-corruption strategy(SGRK.kz n.d.: 12) largely prescribes general anti-corruption actions to be taken by all public bodies, but in one passage highlights the potential role of digitalisation in preventing corruption in the education sector (SGRK.kz n.d.: 12). Similarly, the only reference to the sector in Kyrgyzstan’s 2025-2030 strategy is that corruption was still being observed on an everyday basis in the provision of public services, including education (Shaillo.gov.kg n.d.: 1).

In other cases, countries have committed to develop sector-specific plans for the sector. For example, in 2019, Uzbekistan adopted a presidential decree titled “On measures to further improve the anti-corruption system in the Republic of Uzbekistan”. This included a commitment to draw up a specific road map for curbing corruption in higher education for the 2019-2020 period (UNESCO-IIEP 2020). In Kazakhstan, the Ministry of Education signed a memorandum of understanding with the national anti-corruption agency to develop an anti-corruption plan for the sector (OECD 2023:6). Kyrgyzstan has also reportedly developed an anti-corruption plan for the education sector (OECD 2024a: 29); similarly, Uzbekistan has sector-specific anti-corruption roadmaps on pre-school and school education, and higher education, but the OECD (2024c: 16) notes these have not been made public. In general, this desk review was unable to find publicly available, education-sector specific corruption plans or any relevant related data.

Institutional responses

Poisson (2010: 11) describes how decentralised responses to corruption in the sector – for example, in administrative and financial decision-making – can be effective, but need to be backed up by strengthening institutional and individual capacities.

In addition to national level responses, some education institutions across Central Asia have established their own commitments and measures to address corruption, especially within the tertiary sector. For example, Eckel (2021: 228) notes that Kazakh universities’ relative level of autonomy gives them the potential to pursue their own policies more effectively, including anti-corruption measures. In Kazakhstan, more than ten universities have collaborated to establish an Academic Integrity League, which aims to uphold ethical conduct and standards through various measures such as the operation of a research ethics committee and quality assurance processes; its membership also includes the national anti-corruption agency (Academic Integrity League n.d.).

The National University of Uzbekistan in Tashkent has its own anti-corruption compliance monitoring management division (National University of Uzbekistan 2022). The division undertakes various anti-corruption measures within the university, such as corruption risk management, monitoring public procurement processes for potential conflicts of interest, undertaking internal accountability investigations in response to reports and raising awareness about corruption among staff and students (National University of Uzbekistan 2022). Uzbek national authorities have reportedly developed a rating system for assessing the effectiveness of anti-corruption work in educational institutions (OECD 2024c: 25).

Regional initiatives

There are several regional bodies and initiatives active on the topic of corruption in education. The Anti-Corruption Network for Eastern Europe and Central Asia (ACN) – a regional anti-corruption programme established under the OECD Working Group on Bribery – has addressed anti-corruption at the sectoral level by, for example, providing expert workshops (OECD 2023: 2-3). All five Central Asian countries are currently members of the network (OECD 2023). During the fourth round of the Istanbul Anti-Corruption Action Plan country monitoring programme, the Kazakh government chose to focus on the tertiary education sector, and the ACN supported the review and identified policy recommendations. This included, inter alia, recommending that Kazakh authorities increase transparency in the process of accreditation of universities’ educational programmes and to intensify the prosecution of criminal, administrative and disciplinary corruption offences in the higher education sector (OECD 2018: 56-57).

The UNESCO Office in Almaty (n.d.) covers seven countries – Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – and works on improving access to and the quality of education in the region. Furthermore, UNESCO’s International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) maintains the ETICO portal that collects resources on corruption and ethics in the sector, including available studies from Central Asia. IIEP has furthermore implemented anti-corruption and ethics workshops in the region, including in Uzbekistan (UNESCO-IIEP 2020).

Risk assessment

A key anti-corruption response in the education sector is undertaking a risk assessment to identify potential corruption risks and identifying mitigation measures to try to prevent these from manifesting. Hallak and Poisson (2007: 70-71) explain that risk assessments can be done for virtually all areas of educational planning. Kirya (2019) emphasises that risk assessment and designing mitigation strategies be a locally owned and locally led process to maximise effectiveness. The OECD has developed a risk assessment method specific to the education system called the Integrity of Education Systems: A Methodology for Sector Assessment (INTES).

There is some evidence of Central Asian authorities engaging in risk assessment practices within the sector. In Uzbekistan, an Anti-Corruption Laboratory was established through the initiative of the national anti-corruption agency and a thinktank called the Yuksalish Movement. The laboratory carried out a risk assessment of Uzbekistan’s examination and certification processes, including the technological system to store data on grades obtained (Gafurov et al. 2024: 6). It recommended several mitigation measures such as implementing improved preventive controls in the system, ensuring video monitoring of examinations and increasing penalties against identified cases of cheating in examinations.

Similarly, in response to a string of embezzlement incidents, the Kazakh authorities conducted a risk assessment of the public financial management across the education sector and recommended mitigation measures, such digitalising the budget planning process and integrating the national educational database which hosts financial data with the database systems of other ministries and agencies to better detect anomalies (Gov.kz 2024). Tajik authorities reportedly carried out a corruption risk assessment of the education sector to generate data for its aforementioned strategy (OECD 2024b: 16-17).

Codes of conduct

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:9) hold that codes of conduct, when backed by training and enforcement mechanisms, can lead to greater integrity standards within a school or university. Poisson (2010: 19) stresses that the active involvement of teachers and lecturers in the development and implementation of such codes is needed to ensure they are sufficiently tailored.

Further, the OECD (2021: 76) argues that “establishing codes of conduct might be especially relevant in Eastern European and Central Asian countries because there are concerns about the integrity of teacher activities, particularly regarding absenteeism or offering private tutoring to students, and how those activities can affect their classroom behaviour”. It also notes that codes can help standardise processes for hiring and dismissing teachers for misconduct, which have historically been of a more arbitrary nature in the region (OECD 2021: 76).

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:9) explain that codes can be developed at the national level or within schools and universities. In Uzbekistan, the code of ethics of Fergana State University contains numerous provisions related to corruption, such as requiring professors, lecturers and the student body to report any incidents of corruption they encounter (Fergana State University 2023: 5). At the level of secondary education in Uzbekistan, Ibadullayevich (2022: 50-51) explains that teachers are governed by provisions of a civil code that is applicable to all civil servants, but this has gaps, such as a lack of clarity around the rules for accepting gifts. Ibadullayevich therefore calls for the introduction of a tailored code of conduct for teachers working in secondary schools.

Awareness raising and training initiatives

Initiatives to raise awareness of corruption and provide training to counter it can be introduced for service providers and users within the education sector. These measures can inform people about their rights and ability to report wrongdoing and about their obligations and ethical norms more widely to discourage them from instigating corruption.

Educational institutions are often thought to be a good environment in which to instruct young people about the costs of corruption and what they can do to resist the practice. Akmatjanova et al. (2014: 6) argue that when young people experience bribery as a normalised practice in Kyrgyz universities, this can lead them to reproduce such behaviour at later stages of life.

Kirya (2019: 44-45) explains that integrating corruption education in school curricula is a long-term anti-corruption strategy mandated by the United Nations Convention against Corruption, and that additionally experts such as national anti-corruption agencies can be enlisted to deliver ad hoc training. According to the OECD (2019: 54), Uzbekistan has integrated obligatory modules on corruption into the curricula of secondary and vocational institutions. Furthermore, educational institutions across Uzbekistan conducted over 500 initiatives to promote awareness of preventing corruption in the sector between 2016 and 2019 (OECD 2020: 38).

There is also an important role for civil society in raising awareness about corruption in the education sector. Transparency International Kyrgyzstan (n.d.) has published an education-sector specific breakdown of legal instruments, detailing citizens’ rights and what behaviour amounts to violations of the law; for example, it explains that parents have the right to refuse paying informal fees without facing repercussions.

Reporting channels

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:10) highlight the importance of the availability of confidential and safe complaint channels in the education sector accompanied by whistleblower protection safeguards, enabling students and staff to report suspected corruption without fear of retaliation.

The OECD recently commended Kazakhstan (OECD 2023: 6) for introducing reporting channels allowing students, parents and teachers to lodge complaints within the education sector. They can use a hotline to reach various authorities with any grievance, such as territorial education departments, the quality assurance committee of the Ministry of Education and the ombuds office (Zakon.kz 2024).

Similarly, in Tajikistan, the department of education runs a hotline allowing citizens to report corruption and other malpractices through phone calls, WhatsApp or email. In 2025, it encouraged people to use the hotline to report encountering any demands to pay informal fees for school repairs (AsiaPlus 2025).

Accountability

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:9) emphasise the importance of applying consistent and dissuasive administrative and/or criminal sanctions to deter corruption in the education sector, as well as frequent inspections of education facilities. Indeed, a study by Bussen (2017) concluded that when the private American University of Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan, introduced an increase in wages for staff in combination with greater accountability responses (where those proven to have taken bribes were dismissed), it led to a reduction in corruption levels comparable to other institutions.

In some Central Asian countries, sanctions against corruption, including in the education sector, are severe. In Kyrgyzstan, the government has implemented a large-scale anti-corruption drive in the education sector over the past few years, which has reportedly resulted in 42 people being dismissed from their positions – with 34 facing criminal charges – and the confiscation of the proceeds of corruption amounting to 207 million soms (approximately US$2.4 million) (24kg 2025).In one case from Turkmenistan, education sector officials convicted of corruption were given prison sentences of more than ten years, with large portions of their property confiscated too (Acca 2020b).

However, sanctions should be implemented in a fair and consistent manner. Lapham (2017: 3-4) found that, insofar as formal accountability mechanisms existed in Tajikistan’s education system, there was often selective enforcement. In some cases, non-punitive approaches may also be preferable. Silvoa (2009: 171-4) recognised the high prevalence of private tutoring in Central Asia and its negative implications for the quality of public teaching, but concluded a full ban and sanctions would be difficult to enforce and would impose hardship on the teachers engaging in the practice to make ends meet. Instead, Silvoa (2009: 171-4) argued for the monitoring and regulation of private tutoring to prevent it from leading to corruption, as well as ensuring adequate salaries for teachers to improve morale levels.

Public financial management

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:8) hold that “[t]ransparent and participatory budget processes need to be in place to monitor how resources are being allocated and allow public scrutiny and control over the use of education resources”. In their view, strengthening public financial management in the sector can be aided by open data tracking measures and regular audits (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017:8).

In 2020, as part of an open budget initiative, Kazakhstan introduced an interactive map enabling users to track the allocation and expenditure of education funds (Жунусова 2020). In addition, under Kazakhstan’s system, salary rates can be tracked and educational institutions’ requests for budget dispersals must be made electronically so they can be tracked (Тукушева 2024). Furthermore, biometric verification was introduced for signatures on payment documents to counter risks of forgery (NurKZ 2024). However, an interviewed public finance expert argued that a set of other measures to reduce corruption risks, such as mandated regular reporting and parliamentary and civil oversight mechanisms, should also be introduced to ensure these open budget measures lead to greater accountability (Kazinform 2023).

In recent years, Uzbekistan has scaled up participatory budgeting mechanisms in which a dedicated portion of the national project is to be spent on projects for which the public vote (Yuksalish 2024). The initiative (Yuksalish 2024) monitored the implementation of 433 such projects in 2023, 201 of which concerned improvements in the education sector. In 28% of the monitored projects, it identified shortcomings, such as the construction of a school building that was classified as completed, although the walls were unstable and much of the equipment had not been installed. Nevertheless, Yuksalish (2024) noted that the public generally had high levels of support for the participatory budgeting mechanism and offered recommendations to improve the system; for example, local residents could have a greater oversight role to ensure projects are implemented to a sufficient quality.

Merit-based recruitment

According to Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017: 9) “[t]ransparent and meritocratic hiring practices can help ensure that only teachers with sufficient qualification and experience are appointed”. Fair recruitment can reduce risks of favouritism and nepotism, as well as ensure that prospective candidates for positions in educational institutions have obtained the requisite level of academic certification.

In its review of Eastern European and Central Asian countries, the OECD (2021: 84) commends the practice of certification examinations for teachers,95892b514aa6 especially in environments where there have been concerns about the integrity of teacher appointment processes. While few countries in the region had implemented these as of 2021, by 2023 Kazakhstan had introduced such examinations as part of its recruitment practices, which also include an analysis of potential conflict of interest risks (OECD 2021: 84; OECD 2023: 6).

Other examples suggest merit-based recruitment should be introduced carefully. Bekmurzaev (2023) describes how upon introducing a competitive recruitment process, Kyrgyz authorities simultaneously decided to dismiss school principals that had been in their positions for more than five years. This reportedly violated the labour code, and the recruitment process for their replacement – while open and transparent – was lengthy, which led to high numbers of unfilled posts.

Merit-based processes are also relevant for exams, such as those are taken as a basis for admission to tertiary institution. With a stated goal of countering corruption, Kyrgyzstan was the first state in Central Asia to introduce a merit-based national university admission exam, which also facilitated the possibility of obtaining scholarships for high performance (Eckel 2021: 100). According to Eckel (2021: 100), this helped further equal access to higher education and support for rural youth.

- For example, the Regional Anti-Corruption Platform for Central Asia – a UN-facilitated hub for anti-corruption practitioners – consists of these five countries.

- All five Central Asian countries declared themselves independent upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Since then, their historical trajectories have differed markedly. For example, Batsaikhan and Dabrowski (2017) state that Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have transitioned towards market economies at a faster rate than the other three countries. In terms of governance, Nurdilda (2025) describes how Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have all experienced democratisation at varying rates in recent years, yet authoritarianism has remained largely entrenched in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

- As this estimated level of expenditure is determined by the level of GDP in the national economy, a higher percentage in one country compared to another may nevertheless still be insufficient to meet the education needs of the entire population.

- The OECD (2021: 84) describes certification examinations as external validation tools to ensure that that teacher candidates have the knowledge and competences needed to be effective teachers.