Query

Please provide a summary of evidence on corruption and trafficking in flora and fauna (with a focus on wildlife, timber and other non-timber forest products) in Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam, as well as the national and regional level responses to these.

Introduction

Southeast Asia is frequently classified as a global hotspot for trafficking in flora and fauna. This Helpdesk Answer focuses on the documented role of corruption as an enabler of trafficking in the region (Wyatt and Cao 2015: 8), where complicit public officials3397e41262a7 abuse their power to facilitate trafficking, often colluding with criminal organisations or other private actors in the process. There is a wealth of literature (especially from multilateral and non-governmental organisations) looking into trafficking with a wider lens and go into more detail about the species most at risk, as well as smuggling routes and modalities used. While this Helpdesk Answer maintains a focus on corruption, interested readers are invited to consult the sources contained in the list of references for more detail on these other aspects.

The first section gives an overview of trafficking in flora and fauna with a focus on animal, timber and non-timber forest products (NTFPs) and related concepts, describing their links with corruption. The second section collates evidence on how these dynamics manifest in the region with a particular focus on three Southeast Asian countries: Lao PDR,cb370d439a23 Thailand and Viet Nam.222f069ce845 In the third and final section, is a non-exhaustive description of measures that have been introduced in the region and these three countries to counter the role corruption plays in trafficking, as well as recommendations from the literature on where improvements are needed.

Corruption and trafficking in flora and fauna

Terminology

Trafficking in flora and fauna (or wildlife) is recognised as a significant threat to the population numbers of various species worldwide (OECD 2019: 16), as well as fuelling significant levels of biodiversity and forest loss (UNODC 2023: xii).72e2505f4355 As such, Target 15.7 of the Sustainable Development Agenda calls on states to “[t]ake urgent action to end poaching and trafficking of protected species of flora and fauna and address both demand and supply of illegal wildlife products” (UN n.d.).

While noting there is no universally accepted definition of wildlife trafficking, the UNODC (n.d.) explains that:

‘Wildlife trafficking involves the illegal trade, smuggling, poaching, capture, or collection of endangered species, protected wildlife (including animals or plants that are subject to harvest quotas and regulated by permits), derivatives, or products thereof.’

This framing contains several notable elements. First, it does not restrict trafficking to the act of trading or smuggling but includes the acts which are committed to source fauna and flora species such as poaching, capture and collection.

Second, it stipulates that these acts must be illegal to constitute trafficking. For international trade, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) distinguishes between the legal and illegal trade in wildlife species (UNODC 2018). While CITES does not per se require signatory countries (185 at the time of writing) to criminalise trafficking in the wildlife species it lists, an estimated 169 countries do have such provisions in place; furthermore, many countries make it illegal under their national law to trade in additional species which are not listed as such in CITES (UNODC 2025a: 30). Conversely, in terms of domestic trade, there are discrepancies at the national level; for example, unlike in many parts of the world, the domestic ivory trade in many Southeast Asian countries is legal, albeit subject to restrictive quotas meaning that most ivory in circulation in the region is still suspected to be illegal (UNODC 2019: 111-12).

This co-existence of legal and illegal trading systems is often exploited by corrupt officials. For example, customs officers may provide fraudulent paperwork to certify a shipment is part of the legal trade, making detection difficult (UNODC 2019: 119).87a9b8433f68 The Basel Institute on Governance (2021: 3-4) describes how traffickers rely on corrupt officials and government agencies to help them launder illegally sourced timber into legal markets.

Third, it notes that wildlife trafficking covers a wide range of flora and fauna species. As such, this Helpdesk Answer focuses on trafficking in animals, timberf97ef85c0348 and other non-timber forest products (such as wild plants).f09fd0361d39 Nevertheless, these are often dealt with isolation in the literature where different framings such as “forest crime” are sometimes used to cover illegal logging and timber trafficking, which may equally also be subject to other legal frameworks (UNODC 2025a: 30). Regardless of the lens applied, the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA n.d.a) explains that wildlife and forest crimes have significant overlaps, including similarity in trafficking methods and the reliance on corrupt networks to facilitate the sourcing and trading of these products (EIA 2021: 18).

The role of corruption along the trafficking supply chain

A review of the available literature suggests that, rather than being an incidental topic, corruption acts as a key enabler of trafficking in flora and fauna across various stages of the supply chain.

This includes facilitating the sourcing of flora and fauna products. For example, high-level officials may illegally grant companies land concessions for timber extraction (Baez Camargo and Burgess 2022: 10), while for animals, corrupt officials may commit fraud or even forgery when issuing permits for hunting or captive breeding in return for kickbacks (Broussard 2017: 125; Wyatt et al. 2018; Wyatt and Cao 2015). In their interviews with Interpol staff, Wyatt and Cao (2015: 13) found that government employees may even steal blank CITES permits and sell them to wildlife traffickers. In some cases, illegal logging is carried out by local communities primarily as a means of subsistence who may also resort to informal payments to public officials to secure access to these resources, while at the same time being highly vulnerable to displacement and the other risks linked to corruption perpetrated by companies and high-level officials (UNODC 2023: 23).

At the point of product transportation, various public officials are typically involved. For example, in terms of cross-border trade, each country appoints a management authority responsible for the implementation of CITES that should “attest the legality of the export, import or re-export”; at the same time, customs officials located at seaports, airports or land borders normally also verify the validity and authenticity of documentation (Broussard 2017: 125). Such officials can be susceptible to petty corruption to allow illegal shipments unobstructed passage (Baez Camargo and Burgess 2022: 10) or provide fake certification to mask traded products as legal (Zain 2020). Relatively higher bribes may be exacted to facilitate the trafficking of scarce species compared to less scarce species (Wyatt and Cao 2015:33). In relation to trafficked timber, Humphreys (2016: 170) explains that a wide range of information can be falsified by officials such as the origin and age of the timber as well as the actors involved in supply and handling.

Corruption also occurs at the point of sale where, for example, police or other supervisory officials turn a blind eye to the sale of wildlife products (Zain 2020), while corruption can facilitate the laundering of the proceeds from the sales of fauna and flora9875108bfd48 (Bergin 2025). In some cases, corrupt officials may return seized products to the traffickers (UNODC 2019: 134). There is also evidence suggesting that the flora and fauna can themselves be used as objects of corruption in the form of a gift or bribe (Davis et al. 2025: 1529) or as a means for laundering proceeds from other illicit activities (Amerhauser 2023: 15-16). Furthermore, corrupt criminal justice actors and patronage networks can help win impunity for traffickers and obstruct investigations or prosecutions into cases (Wyatt et al. 2018; Wyatt and Cao 2015).

While comparatively less has been published on the scale and nature of corruption in NTFPs, Timoshyna and Drinkwater (2021: 1) state that there is a similar role of corruption across supply chains, such as in wild plants. They highlight a range of corruption risks occurring across the following stages: access to NTFP resources, purchasing from harvesters, trading and transportation, export and import, final product manufacturing and sale, and consumption (Timoshyna and Drinkwater 2021: 6-7).

The literature highlights a range of factors that come together to drive these forms of corruption. The UNODC (2023 xi-xii) explains that, given that the majority of the world’s forests are publicly owned, public officials responsible for forest management become natural targets for corruption attempts by actors wanting to illegally exploit resources. Broussard (2017: 125-126) explains that low salary levels can act as a driver, and that CITES management authorities are often understaffed and officials under-paid, making them susceptible to attempts to corrupt them. Baez Camargo and Burgess (2022: 5) explain that informal governance systems around wildlife trade are often entrenched in local contexts, and corrupt behaviour can become normalised, making it difficult to change. In their study focusing on Asia, Wyatt et al. (2018) argue that it is not just individual corrupt acts which enable trafficking to occur but also “corrupted structures” spanning the criminal justice system, as well as local political and economic environments, such as if political figures collude with and protect traffickers. Wyatt and Cao (2015:7-8) describe how the relationship between corruption and trafficking may be more prominent in environments where there is a lack of accountability, where civil society is weak and where poverty is widespread. Similarly, they highlight that corruption is driven by the local and international demand for wildlife products, which may be sought after as collector’s items, food and traditional medicines, and processed commodities (Wyatt and Cao 2015: 33).

Three profiles from Southeast Asia: Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam

Southeast Asia is generally considered a global hotspot for trafficking in flora and fauna (OECD 2019: 17). Its traditional medicine and food markets are key destinations for the global illegal wildlife trade (Amerhauser 2023: 16-17), such as ivory and rhino horn trafficked from Africa (UNODC 2019: 5). The region is also a source for many sought-after species such as the critically endangered Siamese rosewood tree, which is native to Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam (Barstow et al. 2022:1-2). In terms of NTFPs, Phelps and Webb’s (2015) study found that there is a large commercial trade in wild, protected ornamental plants in the region, concentrated in Lao PDR, Thailand and Myanmar; similarly, Hinsley (2018) found the region is used to source illegally traded wild orchids.

Trafficking in the region can be a lucrative enterprise; for example, estimates indicate that smuggling Siamese rosewood across the Lao or Vietnamese border to China can increase its value almost tenfold (GI-TOC 2021). In addition to the severe environmental harm, evidence suggests that illicit financial flows generated by crimes such as trafficking in flora and fauna constitute significant financial losses for the region (Bergin 2025).

Figure 1: Map of Southeast Asia

Source: MapChart.com

A diversity of actors engages in trafficking across the region. Some of the most powerful currently active wildlife traffickers are reportedly companies, individuals and families that have established a foothold in the region since the 1980s and “have formed well-established supply chains made up of wild animal and plant specialists, smuggling specialists, financiers, and corrupt officials” (ACET 2019: 5). Regionally active criminal organisations – which may also be involved with other transnational crimes such as the smuggling of narcotics – typically outsource the sourcing and transportation of flora and fauna products to smaller, local actors (UNODC 2024: 45). Similarly, the UNODC (2019: 16) describes how large national and multinational enterprises are often at the forefront of purchasing, transporting and selling illegal timber across the region, although they typically recruit local brokers to liaise with government officials. In some cases, criminal syndicates also are active in other regions; for example, the OECD (2019: 24) describes how many traders of African ivory also engage in trafficking of Asian species such as birds, pangolins and tiger parts.

While the trafficking of flora and fauna also occurs domestically, the volume of flows occurring across borders is considerable. Several Southeast Asian countries are source and transit hubs for the illegal wildlife trade with China, one of the biggest consumer markets (Jiao et al. 2021). Some of the greatest risks are concentrated in border areas, such as the Golden Triangle between Lao PDR, Myanmar and Thailand (Amerhauser 2023: 12-13). Border crossings between Viet Nam and China and Lao PDR are not only hubs for smuggling wildlife and timber but are also locations for major processing centres of ivory, rhino horn and rosewood (EIA 2021: 8). Land borders, ports and airports are reportedly hotspots of corruption (OECD 2019: 79-80).

Southeast Asia generally also contends with reasonably high levels of corruption. In their review of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries (excluding Brunei Darsallam, Lao PDR and Singapore), Schoeberlein (2020: 2) found that while estimated levels of bribery to access public services had dropped, bureaucratic corruption – such as bribery to obtain licences or permits – remained a challenge due to the presence of highly politicised public sectors. Scholars have described how long-established systems of patronage tend to determine control over natural resources in the region, and private clients must develop close ties with the responsible government actors to gain access (Knape 2009; Haefner 2021: 100).

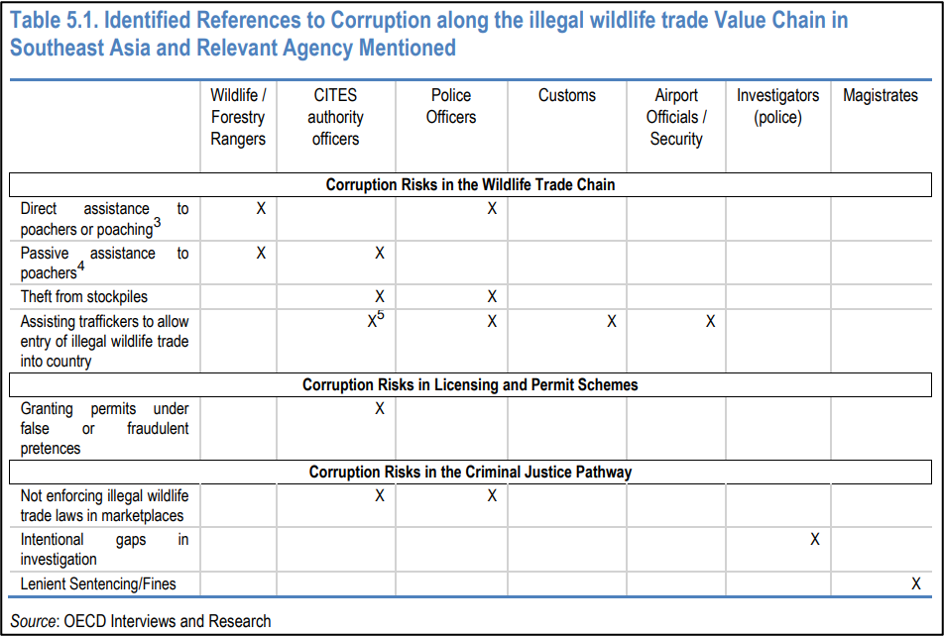

However, it can be difficult to find national level data for corruption cases related to trafficking. For its 2019 study, the OECD carried out semi-structured interviews and collected data fromopen-source media incidents related to corruption risks in Southeast Asia for 2008-2017. It developed a typology of corruption risks alongside the illegal wildlife trade value chain in Southeast Asia and listed the category of public official or agency most relevant to each risk (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Corruption risks alongside the illegal wildlife trade value chain as identified in an OECD study of Southeast A

Source: OECD 2019: 71

Indices

While there are no indices available that directly attempt to measure levels of corruption enabling trafficking, there are measurement tools which explore these in isolation. The table in this subsection collects data on Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam from three indices:

Corruption Perceptions Index:Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) ranks 180 countries and territories worldwide by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. The results are given on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean)(Transparency International 2024).

2023 Organised Crime Index: in its Global Organized Crime Index, GI-TOC calculates the flora and fauna crimes on a scale from 1.00 to 10.0 based on experts’ assessments of various risk factors (GI-TOC 2024:42). The measurements include trafficking and trading in flora and fauna covered under CITES as well as relevant national law, along with other crimes such as poaching and illegal possession of species.

Timber Legality Dashboard: the scores (ranging from 0 to 100) on the Timber Legality Risk Dashboard are informed by a combination of factors, including the existence of a legal framework on illegal logging as well as secondary scores related to governance and corruption risks. According to the dashboard, “Countries scoring less than 25 are considered ‘lower risk,’ countries scoring between 25 and 50 are ‘medium risk’ and countries scoring above 50 are ‘higher risk’” (Forest-Trends 2022a). There is no global ranking of countries available.

The most recently available scores for Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam suggest that levels of corruption and levels of trafficking in flora and fauna are generally high, although with not insignificant variations. For example, indices suggest Lao PDR currently faces higher levels of risk for flora crime and timber trafficking.

Lao PDR

In its 2023 mutual evaluation report (MER), the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) determined that Lao PDR faced high risks for environmental crimes and related proceeds including trafficking in wildlife and forestry offences (APG 2023: 16), but that national government actors did not appear to fully acknowledge this (APG 2023: 34).

Lao PDR’s border areas with China, Myanmar and Thailand have been identified as hubs for the illegal trade in fauna species (van Uhm and Zhang 2022). The country hosts captive tiger breeding facilities for tigers and tiger parts, which are then trafficked further across the region (APG 2023: 34; GI-TOC 2023a: 3-4). Lao PDR is also a source country for many unique species of flora such as rare orchids which are targets of trafficking (UNODC 2014: 1).

In recent years, the government established multiple special economic zones (SEZs) where flora and fauna, including timber, are trafficked and which also host casinos used to launder the proceeds of these crimes (Amerhauser 2023: 23); the high level of risk with the SEZs have also been recognised by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in its 2023 mutual evaluation report. In their study, van Uhm and Zhang (2022) found that the volume of wildlife being traded in the SEZs fluctuated due to various factors, such as if inspections by local authorities are low, which may be explained by the corruption of customs officials.

Lao PDR is one of the world’s leading sources for Siamese rosewood which fuels the majority of illegal logging in the country (GI-TOC 2023a: 3-4). It was reportedly common for corrupt officials at border checks to misdeclare rosewood exports as lesser value species, especially to Viet Nam (Humphery 2016: 17); in 2016, an export ban of rosewood was introduced which has curtailed the trade, but is still allegedly circumvented by corrupt officials (GI-TOC 2023a: 3-4; Forest-Trends 2022a: 9-10; EIA 2021: 15).

Illegal logging is reportedly facilitated at the point of land allocation, where provincial and even ministerial level state officials exceed their mandates and issue companies concessions for large-scale logging (GI-TOC 2023a: 3-4; Forest-Trends 2022a: 9-10). In their study, Hett et al. (2020) reviewed a database of national land concessions in Lao PDR, including in the forestry sector, and approximately half of them were not compliant with national laws and regulations, marked by the absence of required key legal documents (Hett et al. 2020: xii). According to a report from Mekong Eye (2024), “land grabs” for the purpose of illegal logging persist, and some government actors provide approvals and concessions t0 Chinese companies without complying with national frameworks.

According to the GI-TOC (2023a: 5), Lao PDR’s centralised state “provides ample opportunities for state-embedded actors to engage in corruption and facilitate criminal markets, such as the illegal wildlife trade and illicit logging industry”. Indeed, evidence suggests trafficking in flora and fauna may be backed by the complicity of high-level political actors and even state endorsement of the practices. A journalistic investigation published in the Guardian in 2016 alleged that senior officials from the office of the prime minister had over a period of a decade facilitated three leading traffickers’ operations in which “hundreds of tonnes of wildlife” passed through border crossings, including by granting quotas and approvals for tiger farms in violation of the country’s CITES commitments; the publication cited evidence that such agreements had “yielded a profit of hundreds of thousands of dollars for the Lao government treasury" (Davies and Holmes 2016).

Studies in the mid-2010s highlighted an almost complete absence of enforcement (Smirnov 2015: 89-90). A 2014 study by UNODC (2014: 23) found that Lao PDR’s department of forest inspection relied mostly on administrative sanctions and referred almost no serious cases for illegal timber or wildlife trade for prosecution, making it unlikely that corrupt public officials would be deterred. The EIA (n.d.b) found Lao PDR had a poor track record of criminal justice responses, and few known convictions for corruption related to illegal wildlife trade cases since 2014. However, some sources recognise improved efforts in recent years to curb corruption linked to illegal logging. Forest-Trends (2022a: 9-10) highlights a 2019 case in which 33 officials in Xieng Khuang province were disciplined for taking bribes, the large majority concerning the illegal timber trade. The GI-TOC (2023a: 3-4) and Forest-Trends (2022a: 1) have observed that enforcement bodies, such as the provincial forest inspection, are scaling up efforts to enforce illegal logging laws but they lack sufficient resourcing.

Thailand

According to the GI-TOC (2023b: 3-4), Thailand also hosts one of the largest illegal wildlife trade markets in the world and acts as a source, transit and destination for a range of flora and fauna. Trafficking in products such as bear bile and tiger parts is reportedly facilitated by corrupt officials at land border crossings between Thailand and Lao PDR and Myanmar (OECD 2019: 83).In their study of illegal trade in wild ornamental orchids in Thailand, Phelps (2015: 7) found that in some cases traders were permitted to sell openly, but at some sites it was expected that they pay bribes to local law enforcement and forestry officials. Trafficking in wildlife reportedly occurs at Bangkok International Airport; the OECD (2019: 79) describes a 2017 case in which a senior official from the Ministry of Justice and two civilians attempted to bribe customs officials to allow the passage of rhino horns; they were eventually convicted for smuggling, but no corruption related laws were used to prosecute the official in question.

The trafficking of Siamese rosewood is a major problem, especially in eastern Thailand and is often driven by Cambodian criminal groups (EIA 2021: 16). Lewis (2021: 178-179) describes how a group of villagers from a background of poverty relied on illegal logging for their income, but were also exploited by traffickers who supplied them with and made them dependent on narcotics. Government officials in charge of protected areas have reportedly facilitated illegal logging and timber trading (GI-TOC 2023b: 3-4), including by exchanging tenure and use rights as a result of bribery and providing fraudulent land permits and exploiting exemptions under the CITES (Forest-Trends 2022b: 9).

Lewis (2021) explains how trafficking in timber in Thailand is often perpetrated by powerful companies and family-run criminal organisations who oversee entrenched networks of corrupt government officers, police and even military actors, which makes it difficult to root out their influence. The GI-TOC (2021: 4) described how, in 2014, Thailand’s financial intelligence unit began investigating suspicious levels of wealth of a Thai family, and found evidence linking them to a Siamese rosewood trafficking network between Lao PDR and Viet Nam and a multimillion dollar money laundering operation. After being arrested, one of the ringleaders of the network reportedly attempted to bribe police officers (GI-TOC 2021: 6).

Available evidence points to some enforcement efforts against corrupt officials involved in trafficking, although this does not appear to be commensurate with the scale of the threat. The OECD (2019: 72) found that, in the 2010s, Thailand’s national anti-corruption agency had, in comparison to its regional counterparts, launched more investigations into public officials suspected of facilitating wildlife trade, although these were still few (OECD 2019: 72). Similarly, in several instances, public officials have been arrested for facilitating timber trafficking (Forest-Trends 2022b: 8).

In its 2017 MER report of Thailand, the FATF highlighted a case of attempted bribery of a public official linked to the smuggling of rosewood (APG 2017: 18; 67). In 2019, a provincial level chief of the natural resources and environment office was arrested for taking a bribe in exchange for trying to return timber to traffickers that had been seized at the border with Lao PDR (Forest-Trends 2022b: 8). In 2023, a joint operation undertaken by law enforcement authorities led to the arrest of the head of the department of national parks, wildlife and plant conservation who was found with US$150,000 in undeclared cash and gifts; it was suspected that part of these funds was sourced by embezzling from a scheme to construct a trench to reduce human-elephant conflict (Petchkaew 2023). Finally, in 2025, nine people, including a renowned businessman and state officials, were handed lengthy prison sentences for corruption involving the unlawful issuance of land titles in state-owned forest and land reform zones (Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2025).

Viet Nam

Viet Nam is one of the world’s leading hubs for trafficking in fauna species, such as rhinoceros and tiger (Clement and Inglis 2022: 1) as well as ivory, pangolin, turtles and reptiles. The trade is reportedly driven largely by mafia-style groups (GI-TOC 2023c: 3-4) and increasingly takes place over social media platforms (Clement and Inglis 2022). According to the FATF’s 2022 MER report of Viet Nam, government authorities acknowledge wildlife trafficking is a key money laundering risk for the country (APG 2022: 17).

The UNODC (2019: 116) explains that the large number of harbours in Viet Nam, as well as its long land borders with Lao PDR, Cambodia and China, make it a hotspot for wildlife trafficking. Viet Nam reportedly has insufficient numbers of personnel patrolling its borders, and the remote crossings makes oversight of assigned personnel difficult (OECD 2019: 82).

The OECD (2019: 82) notes that corruption among border officials at Mong Cai City, located at the Chinese border, facilitates the illegal wildlife trade; traffickers may directly pay a bribe to border officials that corresponds to the value or quantity of the products, or use the services of local “kingpin” figures who exploit regional political connections to ensure their operations are not obstructed. Interviews in 2015 suggested that it was common for illegal wildlife traders in Nhi Khe village to pay a monthly fee to local law enforcement officers to enable them to sell their products openly and in exchange for information about inspections (Wildlife Justice Commission 2023: 25). The Wildlife Justice Commission (2023: 21) describes a case from 2018 in which a Vietnamese customs official was sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment for embezzling confiscated fauna products from a warehouse for resale.

Viet Nam acts as a key transit country for illegal timber destined for China and hosts a large wood processing sector that often relies on illegal timber trafficked from neighbouring countries such as Cambodia and increasingly from Africa (Forest-Trends 2025: 9-10; UNODC 2019: 16). The smuggling is enabled by corrupt public officials (GI-TOC 2023c: 3-4), including through fraudulent documentation and misdeclaration of species (Forest-Trends 2025: 9-10). UNODC (2025b: 39) states these can also constitute acts of corruption in land management by, for example, bribing evaluators of environmental impact assessments for logging projects to turn a blind eye to misrepresented impacts (UNODC 2025b: 39). It further describes a Vietnamese case where a company obtained permission to log in designated areas, but then also logged outside them and mixed the supply chains of both the illegally and legally harvested timber to avoid detection (UNODC 2025b: 46).

The EIA (2018: 4-5)highlights a 2016 case where officials in the Gai Lai provincial government issued quotas for the import of 300,000m3 of timber from Cambodia despite the latter's log export ban, which incentivised illegal logging in protected Cambodian areas. There were allegations that the Vietnamese officials obtained US$45 per m3 of timber to issue the quotas. The EIA evaluated whether the introduction of Viet Nam’s forest law enforcement, governance and trade voluntary partnership agreement (VPA) with the European Union had ramifications for the illegal timber trade, and found, despite isolated instances of enforcement such as the arrest of a high-profile trafficker, government responses had failed to prevent large volumes of illegal timber form continuing to cross the Cambodian border (EIA 2018: 4-5).

In recent years, the sitting Communist Party of Viet Nam has led an anti-corruption drive, leading to the prosecution of thousands of officials; however, some observers find this campaign has been used to prosecute political opponents (Maslen 2025: 2). Furthermore, petty bribery among law enforcement and other public officials reportedly remains widespread (Maslen 2025: 2). To and Mahanty (2019) argue that provincial government actors are heavily involved in facilitating imports of illegal timber, including for economic development in their region, but this undermines the central government’s legitimacy in the face of commitments to address timber trafficking. Therefore, the central government has responded by “performing” corruption crackdowns on provincial officials in an effort to restore its political legitimacy.

Compared to Lao PDR and Thailand, the role of corruption in trafficking in Viet Nam has been more often a topic of focus in the academic literature where various disciplinary approaches have been taken. To et al. (2014) carried out an ethnographic study tracing the actors trafficking rosewood sourced in Lao PDR through Viet Nam. They found that social networks built on vertical and horizontal relationships and power imbalances help drive corruption, such as where higher-status patrons within and outside state agencies ensure the protection of “lower-status timber traders in exchange for financial and other gifts”.

However, they also found that such corruption can be facilitated by the “familial quality of social relationships” where bonds are built on trust, and that the distinction between public and private actors in an institutional sense does not always hold up to social realities (To et al. 2014: 158). For example, they describe how large timber trading companies court customs and forest protection officials through social rituals (To et al. 2014: 166), and such officials are motivated not only to supplement their low wages but also through their desire to reciprocate these connections (To et al. 2014: 170-71). They also found traffickers may be able to use their networks in law enforcement to buy impunity, citing an alleged case where various state agencies conspired to prevent further investigation of a large timber trading company despite customs agencies locating evidence they had been engaging in illegal trade (To et al. 2014: 168).

In his study on timber trafficking in Viet Nam, Cao (2018: 292-293) interviewed law enforcement and other public officials, providing insights on how corruption can emerge at different stages of the supply chain (2018: 292-293). He reported that forest protection staff may take bribes to turn a blind eye to illegal logging or to leak details about patrol schedules (Cao 2018: 294). When transporting timber, traffickers may bribe a range of actors such as police, local authorities and even the military stationed at the border to facilitate passage, some of whom might assist with transporting the products themselves. Traffickers often pay multiple bribes as the “corrupt officer can only guarantee the smuggling route within his/her vested zone” (Cao 2018: 295). He also noted how corruption can buy impunity, for example, where police officers frustrate investigations against traffickers (Cao 2018: 295), and in most cases, complicit public officers are not subjected to criminal trial but instead receive sanctions such as warnings or transfers which may be an inadequate deterrent (Cao 2018: 297). Due to the widespread role of corruption, Cao (2018: 296) concludes that attempts to control timber trafficking will fail if not accompanied by a crackdown on corruption.

In a later study, Nguyen and Cao (2020) conducted 41 semi-structured interviews with various law enforcement actors, forest protection officers, timber traders and others in Viet Nam. This led them to distinguish between three forms of illegal timber harvesting in Viet Nam: small, medium and large-scale. They find that the literature mainly focuses on the medium-scale harvesting, which is carried out by professional loggers and specialist timber traders and often facilitated by corrupt officials (Nguyen and Cao 2020: 139-140). In contrast, forest based locals may engage in small-scale harvesting primarily for subsistence purposes rather than to secure profits, normally through rudimentary methods and in line with their traditional livelihood practices (Nguyen and Cao 2020: 139-140; 156).

However, they also highlight that there is large-scale harvesting often driven by commercial company owners or high-profile timber traffickers who may also coordinate smuggling and trading and may attempt to influence law enforcement authorities or even policymakers in the permitting process with bribes (Nguyen and Cao 2020: 137). In their view, large-scale illegal timber harvesting in Viet Nam is often masked as legal and not captured by statistics (Cao 2018: 157). They note that even if statistics of detected illegal logging cases in Viet Nam seemed to be declining, the number of cases that involved higher volumes of trafficked timber and a high level of sophistication seemed to be increasing (Nguyen and Cao 2020: 9).

In their case study focusing on fauna trafficking in Vietnam, Wyatt and Cao (2015: 21) found that the scale of the illegal trade shaped traffickers’ use of corruption as a tactic. For example, they found that small-scale traffickers typically only needed to foster corrupt relationships and pay small value bribes to local actors, such as Kiem Lam (forest department) officers. However, for more substantial trafficking operations, it was typically necessary to nurture relationships with senior officials who expected higher bribes. Wyatt and Cao (2015: 21) also found that corruption could assume a networked pattern within public agencies and that, in some cases, rather than there being a few rotten apples entire teams from the Kiem Lam were complicit in wildlife trafficking.

Mitigation measures

This section provides a list of responses and mitigation measures to the role of corruption in facilitating flora and fauna trafficking, highlighting recommendations and examples from Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam and the wider region. However, due to the general lack of publicly available information as well as studies assessing their effectiveness, it is difficult to comprehensively assert the extent to which these responses and measures have been used across Southeast Asia, meaning the examples given should be treated as non-exhaustive and illustrative in nature. Furthermore, the effectiveness and relevance of some of these responses and measures may be contingent on the national political system in place, which in Southeast Asia often are autocratic or closed in nature (Croissant 2022).

Traceability and verification mechanisms

As discussed, one of the main corruption risks in trafficking of flora and fauna concerns the provision of fraudulent documents, such as the misdeclaration of species. A 2017 resolution adopted by state parties to the CITES urged them to:

‘[E]nsure that agencies responsible for the administration and regulation of CITES, particularly with regard to the issuance, inspection and endorsement of permits and certificates, and the inspection and clearance of shipments authorized by such documents, implement measures which aid in the deterrence and detection of corrupt practices; (CITES 2017)

Certification and permit processes should be designed to reduce the scope for discretionary decisions by public officials (Martini 2013: 5) and ensure adequate oversight of the documentation which is required but is vulnerable to abuse across the entire trafficking chain (Wyatt and Cao 2015: 28). In their study focusing on CITES management authorities, Outhwaite (2020: 1) explains that multiple strategies are needed to reduce opportunities for abusing documentation, including the introduction of an e-permitting system to automate processes or, if that is not possible, applying measures to make the verification of paper documents more secure, tamper-proof and subject to oversight. Williams et al. (2016:11) describe other opportunities to enhance the monitoring of licences and permits, such as integrating different stakeholders including civil society in monitoring work and making tracked data available across a wide range of media.

This is closely related to digital systems which help trace the origin of flora and fauna species, and therefore give less discretion to officers in declaring them legal or not. Grant et al. (2021) argue that such electronic traceability systems can more easily detect anomalies and identify red flags; however, they caution that the efficacy of traceability systems in countering corruption can be undermined if authorities neglect to act on the information the systems provide (Grant et al. 2021). Timoshyna and Drinkwater (2021: 11-12) highlight that Thailand has an electronic system for tracing NTFPs which records data such as origin and permits formedicinal and ornamental plants.

Another approach is that private actors should be obliged to carry out due diligence on their supply chains and decrease the demand for trafficked flora and fauna and, with that, the forms of corruption enabling these crimes (UNODC 2023: 49). Viet Nam has started to implement its timber legality assurance system, which sets out a classification, evaluation and licensing scheme that enterprises importing and exporting timber must meet, with a view to complying with EU market standards; however, Forest-Trends (2025: 1) found the system is not yet considered to be robust. Meanwhile, the China National Forest Product Industry Association has introduced a voluntary mechanism, the timber legality verification group standard, where participating Chinese companies in fields such as timber processing commit to setting up their own monitoring mechanism to prevent corrupt practices in timber distribution (Lang and Zhou 2025: 23-24).

Transparency around land management

As attested to above, corruption in the granting of concessions for land use can drive illegal logging and the trafficking of timber. The UNODC (2023: 47) holds that transparency around public land allocation decisions can help deter corrupt behaviour in the forestry sector, arguing that it makes public officials more accountable to the public. It also “inhibits the ability of corrupt officials to use the ignorance of data managed by other public organizations as a shield for their corrupt behaviour” (UNODC 2023: 47). In this regard, they recommend the creation of databases which hold data such as land tenure records, forest management plans and concession agreements (UNODC 2023: 47). A study commissioned by the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) (2021: 6) found that, while the number of such open land information systems were increasing in recent years globally, they often lack complete, accessible and reliable data, making it difficult to measure their impacts in terms of anti-corruption.

As part of a project supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, the government of Lao PDR launched a public inventory of land investments in the 2010s. While noting significant data gaps, Hett et al. (2020) characterise the inventory as a positive measure in the direction of transparency as it enabled greater scrutiny of land concession decisions made by provincial and local government actors. Kenney-Lazar et al. (2023: 100-101) note the conclusions gleaned from the national level data, such as the number of land concessions granted without complying with the national law, appeared to have motivated some government policy changes. This included the introduction of a more rigorous legal framework for land management, although there also appeared to be reversals to government will in recent years as a response to an economic downturn (Kenney-Lazar et al. 2023: 100-101).

Similar transparency orientated recommendations have been made with regards trafficking in fauna. For example, in their case study of Viet Nam, Wyatt and Cao (2015: 37) recommend that a registration and permitting system should be established for wildlife farms, which should be monitored by an independent body.

Internal human resource policies and integrity measures

As described above, a range of public bodies are typically tasked with responsibilities for countering trafficking in flora and fauna, such as CITES management authorities, customs agencies and forest protection/ranger services, and thus are vulnerable to corruption. On the one hand, this necessitates that internal detection and sanction systems are in place within such bodies (UNODC 2023: 45-46). Wyatt and Cao (2015: 15) interviewed INTERPOL staff who suggested that staff rotation policies should be introduced, which reduce opportunities for officials to develop relationships with traffickers, as well as recommending the establishment of internal affairs units within agencies to carry out undercover testing of officers to determine their susceptibility to corruption attempts.

On the other hand, internal measures can be introduced which aim to positively foster integrity among personnel and reduce their propensity towards and tolerance for the corrupt behaviour facilitating trafficking. This was also recognised by the 2017 CITES resolution which encouraged parties and especially CITES management authorities to:

‘[W]ork closely with existing national anti-corruption commissions, and like bodies, law enforcement agencies, judicial authorities, as well as with relevant civil society organisations, in the design and implementation of integrity policies, which might also include deterrence initiatives, such as mission statements, codes of conduct and ‘whistle-blower’ schemes, taking into account the relevant provisions of the [United Nations Convention against Corruption] UNCAC; (CITES 2017)

With regards forest management bodies, the UNODC (2023: 45-46) recommends human resource policies around incentive structures and good working conditions to reduce the likelihood of corruption (UNODC 2023: 45-46). Other commentators also argue that adequate levels and consistent payment of salaries can make it less likely that officials seek to enrich themselves by facilitating wildlife crime (WWF and TRAFFIC Wildlife Crime Initiative 2015: 23; Martini 2013). Cao (2018: 298) explains that some of his interviewees believed that better salaries for Vietnamese forest protection staff would reduce their propensity to engage in corruption, but recognise that studies show higher compensation does not always lead to a decrease in corruption (Cao 2018: 299).

An overview of reward and sanctions schemes in customs agencies found that, in addition to financial rewards, those that address individuals’ non-financial motives can be effective, such as professional pride and recognition through “integrity awards” (Jenkins and Gogidze 2024). The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) organises annual Asia Environmental Enforcement Awards which recognises efforts to counter transboundary environmental crime, and has been awarded to customs officials and criminal justice officials from Southeast Asia countries (UNEP 2018).

In Thailand, newly hired customs officers had to undergo a training course on their code of conduct, including learning about what constitutes ethical behaviour and disciplinary measures that arise in the event of breaches (UNODC 2017). The code of conduct (Thai Customs 2018) outlines several measures towards developing a culture of integrity within the agency.

Encouraging the reporting of corrupt acts can help detect corruption as well as deter the normalisation of the behaviour within agencies. Kohn and Kostyack (2021) state that independent reporting channels and whistleblowing schemes with protection guarantees are important mechanisms for countering corruption that enables wildlife trafficking, given the potential for retaliation. In 2014, the Earth League International (ELI) launched a transnational whistleblowing initiative called WildLeaks, a secure, encrypted system where whistleblowers can anonymously upload reports of environmental and wildlife crime, including suspected cases of corruption (WildLeaks n.d.; Wyatt and Cao 2015: 15). Received reports are assessed by ELI experts who either investigate it themselves, share the information with trusted government and law enforcement agencies, or with media partners (WildLeaks n.d.). A 2020 overview report gave examples of some of the anonymous reports submitted to the platform, including evidence of trafficking in tiger parts in Viet Nam (WildLeaks 2020: 59) and published leaks regarding illegal logging in Lao PDR (WildLeaks 2020: 64). WildLeaks has been also endorsed at the national level; in 2025, it officially launched and disseminated in Cambodia, including being available in the Khmer language (Niseiy 2025).

Prosecuting corrupt actors

In Southeast Asia, levels of enforcement against investigation and prosecution of corrupt officials facilitating trafficking in flora and fauna are generally low (OECD 2019) and, in the most egregious cases, corruption even contributes to impunity for traffickers and public officials.

In its study of Southeast Asia, ACET (2019: 5; 28) explains that wildlife trafficking cases are often solely prosecuted on the basis of wildlife law and often focus on seizing illegal cargo, while arrests of the corrupt enablers of wildlife trafficking are comparatively rare. It recommends countries adopt a multi-prosecutorial approach that makes more use of money laundering, corruption and forgery charges to more effectively deter all actors involved in the supply chain of flora and fauna. The OECD (2019: 12-13; 25) similarly recommended that Southeast Asian governments carry out “anti-corruption investigations by police and anti-corruption authorities on the back of arrests for wildlife crimes to identify and prosecute related criminal networks” as well as engage financial intelligence units in follow-the-money investigations related to wildlife crime.

This may be supported through the establishment of anti-corruption investigation teams that hold specific mandates to address corruption in the wildlife sector (Wyatt and Cao 2015: 11). In 2019, Thailand’s anti-corruption agency created a bureau staffed with specialised officers to pursue corruption cases involving natural resources (OECD 2019: 76). Wyatt and Cao (2015: 36) argue that donors interested in curbing the illegal wildlife trade can direct programming towards enhancing the capacities of law enforcement bodies more widely to detect corruption by, for example, learning technical methods to uncover fraudulent paperwork.

It also depends on the existence of legal provisions at the national level which enable investigation and prosecution.b23f19469a74 For example, the UNODC (2018: 24) recommends that states review the extent to which officials unlawfully providing traffickers with genuine permits and certificates constitutes a corruption offence under their domestic legal frameworks.

ASEAN (2021a: 18-20) has undertaken a comparison of 10 ASEAN members and whether or not key provisions on illegal wildlife trade are reflected in national legislation, and identified significant gaps in some national legal frameworks. For example, unlike Thailand and Viet Nam, Lao PDR only partially regulates aiding and abetting illegal wildlife crime (ASEAN 2021a: 20), an offence of particular relevance for corrupt public officials that facilitate trafficking.

Furthermore, it identified strong variations in the prison sentences and maximum fines which can be imposed, with Lao PDR imposing much lower than the ranges in Thailand and Viet Nam (ASEAN 2021a: 22). Broussard (2017: 120) called for the level of sanctions to be more harmonised within the region, because otherwise individual countries can become safe havens for traffickers.

International and regional cooperation

Given their often cross-border operations, cooperation between criminal justice actors is essential to effectively target networks trafficking in flora and fauna (Jiao et al. 2021). However, in its 2019 study looking at law enforcement authorities across Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam, the OECD found that cooperation between authorities in Southeast Asian countries and those in other regions remained underdeveloped (OECD 2019: 12). Similarly, Jiao et al. (2021) find that cooperation between Chinese and other national authorities in Southeast Asia could be improved by, for example, greater use of mutual legal assistance, extradition and other cooperation outlets under the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC).e350853994ca

Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam are all members of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which has recognised the role corruption plays in wildlife trafficking. For example, the 2019 Chiang Mai statement of ASEAN ministers responsible for CITES and wildlife enforcement on illegal wildlife trade calls for strengthened regional actions to curb corruption and the money laundering risks of illegal wildlife trade (ASEAN 2021a: 17). Elsewhere, ASEAN (2021a: 131) has acknowledged a perception of pervasive corruption with regards wildlife trafficking in the region and that efforts to prosecute such corruption had not been widely publicised.

ASEAN has produced guideline resources such as the ASEAN handbook on legal cooperation to combat wildlife crime and operates two separate working groups that aim to strengthen law enforcement cooperation in countering wildlife trafficking: the ASEAN working group on CITES and wildlife enforcement and the ASEAN working group on illicit trafficking of wildlife and timber (SOMTC) which is hosted under the senior officials meeting on transnational crime (ASEAN 2021a: 17). Police, CITES management authorities and other relevant authorities from ASEAN member states participate in these working groups to improve collaboration and information exchange.

A review of the ASEAN wildlife enforcement network – the precursor to the ASEAN working group on CITES and wildlife enforcement– found it had enhanced law enforcement investigations and also been effective in improving coordination with Chinese authorities (ACET 2019: 15-19). However, the UNODC (2019: 128) cautions that it is difficult to measure the impact of such regional cooperation mechanisms; indeed, from a review of the literature, it is also unclear to what extent such working groups are cooperating to actively target corruption.

Multi-stakeholder approaches

In most Southeast Asian countries, management and responsibilities for enforcing laws and regulations to curb the illegal wildlife trade are split into multiple authorities (OECD 2019: 24). Additionally, according to the Wildlife Justice Commission (2023), wildlife crime and corruption are often treated as two separate issues in law enforcement responses. In cases where they intersect, there is often a need for collaboration and communication between branches of investigatory bodies specialised in corruption and in environmental crime (UNODC 2023: 57).

In some Southeast Asian countries, there are multi-agency task forces called wildlife enforcement networks (WENs) that are typically made up of “police, customs, CITES authorities, prosecutors’ offices and, in some cases, financial intelligence units and anti-corruption agencies” (OECD 2019: 25). However, the OECD found that the recorded use of the structures was infrequent, and most prosecutions and investigations still take place in siloes (OECD 2019: 25). It highlighted that the Thai WEN was an exception, which had been used for the pro-active investigation and successful prosecution of complex illegal wildlife trade cases in which multiple bodies played a role (OECD 2019: 25).

The Wildlife Justice Commission (2023) recommends that joint approaches also take place towards corruption prevention by, for example, engaging multiple stakeholders to identify risks across the entire wildlife supply chain. Similarly, Williams et al. (2016: 14) recommends that donor interventions which relate to the wildlife sector should be backed by credible corruption risk assessment procedures. With support from UNODC, Thailand organised a joint workshop bringing together representatives of various authorities in the environmental sector with customs and anti-corruption law enforcement actors to assess corruption risks related to wildlife trafficking (UNODC 2022).

The Analytical Centre of Excellence on Trafficking (ACET) has recommended the involvement of non-traditional actors in counter-trafficking (ACET 2019: 25). In all of the studied Southeast Asian countries, a 2019 OECD study found evidence of instances in which intergovernmental and non-governmental actors had supported law enforcement agencies in illegal wildlife trade cases through, for example, intelligence gathering and expert legal reviews (OECD 2019: 26).

Scholars also call for measured, consultative approaches which prioritise engaging the local communities affected by trafficking. Timoshyna and Drinkwater (2021: 3) explain that because local harvesters in poor and marginalised regions are typically reliant on trade in NTFPs as a means of livelihood, anti-corruption efforts should account for their interests. They recommend collaboration with community based projects and cite as a positive example a project led by the CSO TRAFFIC in Bac Kan, Viet Nam, in which efforts were made to support local harvesters in obtaining permits to collect legally. The GI-TOC (2023c: 6) highlights that Viet Nam has established a range of law enforcement agencies and community based crime prevention groups to address trafficking in flora and fauna. Across Thailand, the national anti-corruption commission (2024) has reportedly engaged local communities and promoted their role in monitoring risks of corruption related to illegal logging in community forests (Office of the National Anti-corruption Commission 2024).

- While this Helpdesk Answer refers primarily to public officials, corruption can also be perpetrated by private actors where they hold and abuse entrusted power in line with the definition of corruption used by Transparency International. Wyatt and Cao (2015: 12) give the example of a clerk working at a private air freight company who facilitates the passage of trafficked wildlife.

- These countries have been selected as the focus of this Helpdesk Answer, but not on the basis of any specific criteria, such as the estimated national-level exposure to corruption and trafficking. Indeed, evidence suggests that regional counterparts – for example, Cambodia and Myanmar – also face these challenges to a considerable extent (see Bergin 2025).

- While often referred to as Laos, this Helpdesk Answer uses on the official country name Lao PDR.

- For a more comprehensive overview of the impacts of corruption on forest loss, see UNODC 2023: 16-17.

- Conversely, the presence of illegality does not itself connote corruption. For example, building on a definition provided by the Food and Agricultural Organisation of corruption in forest sector (FAO n.d.), the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (n.d.) explains that illicit logging does not in every case entail corruption, but certain elements must be present, such as being perpetrated for the private gain of a public official.

- De Beer and McDermott (1989) defined “non-timber forest products” (NTFPs) as all biological material other than timber, which are extracted from forests for human use. In the literature, these are often also referred to as “non-wood forest products” (NWFPs). The FAO (1999) gives the following non-exhaustive list of examples of NWFPs: “products used as food and food additives (edible nuts, vegetables, mushrooms, fruits, herbs, spices and condiments, aromatic plants, game, insects), fibres (used in construction, furniture, clothing or utensils), resins, gums, and plant and animal products used for medicinal, cosmetic or cultural purposes”.

- Timber is often used as an umbrella term in the literature to include other materials such as pulp, paper or charcoal (UNODC 2019: 126). For more information on the timber species listed under CITES, see CITES and Timber: A Guide to CITES-Listed Tree Species.

- In order to manage scope, this Helpdesk Answer does not go into detail about money laundering and trafficking in flora and fauna as these links constitute a substantial topic in its own right. For an overview of how these manifest in Southeast Asia, the reader is invited to consult Chapter 6 of the 2019 OECD report The Illegal Wildlife Trade in Southeast Asia.

- In its ICCWC indicator framework for combating wildlife and forest crime: A self-assessment framework for national use, the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime provides a self-assessment framework for national actors to assess law enforcement’s ability to effectively counter wildlife crime. This includes an indicator on the existence of provisions against corruption in national legislation that can be used in the investigation and prosecution of wildlife crime(ICCWC 2016: 3).

- The provisions in the UNTOC on extradition, mutual legal assistance and other forms of international cooperation do not apply to all offences, but rather where different thresholds in the treaty are met.