Introduction

Critical minerals are highly relevant in global supply chains, and there is growing political interest in them. Zambia is a significant source of critical minerals, particularly copper and cobalt. It also has notable deposits of lithium, nickel and graphite. Zambia’s contribution to the critical minerals supply chain positions it as a key player in the global supply of minerals crucial for energy transition and technology manufacturing. As such, Zambia sits in the crosshairs of intense geopolitical competition for strategic access to critical mineral value chains (CMVCs).

The high relevance of CMVCs results in an increased risk of revenue leakages due to corruption and tax evasion.

This Issue examines corruption related to Zambia’s critical mining sector. It does so by analysing the corruption and illicit financial flow (IFF) risks in the regulatory and governance regime and by conducting a political economy assessment of the sector. The study also examines the intervention landscape of the sector and highlights potential entry points for interventions and reform.

Illicit financial flows in Zambia

IFFs pose a significant challenge to Zambia’s economic development, draining revenue and undermining fiscal systems. The main forms and channels of IFFs in Zambia are tax related. Tax-motivated IFFs arise mainly from trade misinvoicing and transfer pricing. According to UNCTAD’s preliminary estimations, trade misinvoicing seems to have generated US$44.9 billion (inward and outward) IFFs based on seven major trading partners between 2012 and 2020.0d25129ede56 2023 estimates peg Zambia’s annual loss of revenue due to corporate tax abuse at US$769.6 million – or 2.9% of their GDP.*

While tax-related IFFs constitute the most significant erosion of Zambia’s revenue base, a recent government report on IFFs notes that other important forms and channels of IFFs are from organised crime activities and government corruption.c30943d61f80 Research findings also shed light on specific sources of IFFs related to corruption, such as contract-overpricing and bribery, with extractive industry contracts and infrastructure projects particularly affected.20ea05e14483

The channels for IFFs in Zambia include complex financial transactions such as shell companies, offshore accounts and illicit trade practices. Multinational corporations operating in-country sometimes exploit these channels, over or underreporting the value of their transactions to shift profits out of the country. The mining sector, due to its significant contribution to Zambia’s economy, is especially vulnerable to such practices, with a large portion of illicit flows tied to the misreporting of export values.

The anti-IFF architecture: Gaps and loopholes

Zambia’s approach to tackling IFFs is shaped by a combination of domestic laws, regulatory institutions and international commitments. These frameworks aim to address key drivers of IFFs such as corruption, tax evasion, money laundering and transfer pricing manipulation. However, despite formal commitments and various legislative efforts, the legal and institutional architecture remains fragmented and inadequately enforced, allowing IFFs, particularly those linked to corruption, to persist.

Core legislation in Zambia includes the Proceeds of Crime Act,* the Anti-Corruption Act,8181340430b6 the Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) Act,8925a028ae86 the Penal Codea284d88d6fe5 and the Anti-Money Laundering404020043a5f and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) law.664d761ec0f2 Together, these criminalise financial crimes and provide mechanisms for detecting and prosecuting illicit activities. The FIC plays a central role in monitoring and analysing financial transactions to detect suspicious activity. The Zambia Revenue Authority (ZRA) monitors tax compliance and identifies base erosion and profit shifting, while the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) investigates and prosecutes corruption-related offences. Additionally, Zambia participates in global initiatives such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which promotes transparency in the management of natural resources.

Despite these measures, enforcement of anti-IFF legislation is inconsistent. A major weakness is the lack of coordination among key institutions, especially the FIC, ACC, and ZRA. While the FIC may flag suspicious transactions, follow-up investigations and prosecutions are often delayed or not pursued, particularly when politically exposed persons (PEPs) are involved. Weak prosecutorial independence and political interference further undermine enforcement.

Legal definitions and provisions within the existing framework are often outdated or vague. For example, neither the Proceeds of Crime Act nor the Anti-Corruption Act adequately address issues such as beneficial ownership (BO) or asset layering through complex corporate structures. This loophole is exacerbated by the absence of a public BO register, allowing individuals to obscure illicit financial activities through shell companies or trusts.

Zambia’s AML/CFT law, aligned with international standards such as those set by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), mandates financial institutions to implement due diligence, report suspicious transactions and maintain records. However, enforcement remains weak, and challenges persist due to the limited availability of reliable data on IFFs. Measuring IFFs in Zambia is complicated by the hidden and informal nature of illicit financial activities. Practices such as trade misinvoicing, informal cash transfers and underground economic transactions are difficult to detect and are not reflected in official data. Consequently, estimates rely heavily on proxies, like trade data discrepancies or mismatched tax records, which can be imprecise. On a broader scale, inconsistencies in national reporting standards and poor regional coordination make it difficult to develop a consistent and accurate picture of IFFs across the continent.

In sum, while Zambia has made notable strides in establishing a legal and institutional framework to combat IFFs, significant gaps remain in enforcement, coordination and data reliability. Addressing these challenges will require strengthening inter-agency collaboration, closing legislative loopholes, improving data collection and insulating enforcement agencies from political interference.

Methodology

The study takes a qualitative approach. The point of departure was a survey of existing literature, both published and unpublished.4fdd98e03e3e Then, a law and policy review mapped out the mining sector’s regulatory framework.0bb6a99333a0 A stakeholder mapping exercise was used to identify informants knowledgeable about governance issues in the critical minerals industry. Twenty-one key informant interviews with government, civil society, academic and industry representatives cross-fertilised the desk research. Finally, data from consultative exercises were synthesised with insights gleaned from the desk review to construct a qualitative understanding of the key risk factors for corruption and IFFs in the critical mineral subsector.

A strategic opportunity: Critical minerals and geopolitical shifts of the green transition

According to the International Energy Agency, manufacturers of green energy technologies will need significantly greater quantities of critical minerals (including copper, cobalt, lithium and nickel) in the next two decades.528a663bcc88 The global shortage of these minerals, and Zambia’s notable reserves, have garnered keen interest in Zambia from China, the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom and the Gulf states. China currently dominates the value chains of critical minerals like lithium, cobalt and rare-earth elements (REEs), and Chinese companies have emerged as major players in the mining sector particularly in Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Other global powers have taken note and have sought to dilute this influence by courting Zambia with promises of fairer and ‘cleaner’ investment opportunities. Examples include Zambia’s memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the European Union (EU) on sustainable raw materials value chains8c6a86226bb8 and Washington, D.C.’s MoU with Angola, DRC and Zambiab412f31e0d71 to kick off the Lobito Corridor – hundreds of miles of track from Zambia’s Copperbelt Province to an existing line in Angola, connecting copper mines in DRC and Zambia with ports. The Zambia–EU MoU aims to foster collaboration in the responsible sourcing and processing of critical minerals, emphasising environmental sustainability, social responsibility and economic growth. The partnership will support Zambia in strengthening its mining sector while ensuring that mineral extraction contributes to sustainable development. It also aims to enhance technological innovation, market access and local value addition, aligning with both parties’ commitments to the global energy transition and sustainable economic practices.

The United States has a high stakes interest in developing a complete value chain around EV batteries in the DRC and Zambia, from extraction to assembly line. As a reliable source of critical minerals, Zambia has a unique opportunity to capitalise on opportunities arising from the geopolitical competition for these minerals; however, to effectively do so, Zambia must curb IFFs from the sector.

Contextual framework

Historical overview: Copper mining in an historical and political perspective

Industrial copper extraction has dominated Zambia’s economic and political development since colonial times. Consequently, Zambia assumed that its vast copper reserves would turn it into an industrialised and ‘modern’ state. Even though copper currently accounts for over 72% of its exports, Zambia still has high poverty rates (64.3%)d67710f98145 and high levels of inequality (Gini coefficient of 51.1).83541f726885 Despite attempts to diversify the economy, such as through agricultural production, Zambia’s rural areas are largely underdeveloped. In 2022, 78.8% of the rural population lived in poverty compared to 31.9% of those in urban areas.517d75cc7b14

The Anglo-American Corporation (AAC) and Rhodesian Selection Trust (RST) were the major copper producers from the 1920s onwards. In the late 1960s, the process of nationalisation of the mining sector started,4e6baeb80b5f which coincided with a sharp decline in copper prices following the oil crisis. With the liberalisation of the economy in the early 1990s, and as one of the conditionalities of the IMF, the state company was dismantled, and individual mines were privatised.

Privatisation led Zambians to begrudge the new companies because of massive job losses and increased casualisation of the labour force. In addition, the new companies could generate profits from exceptional world copper prices that followed shortly after privatisation while enjoying generous tax breaks. These had been granted during the privatisation process in the so-called Development Agreements.

Despite the Mines and Minerals Act specifying that mineral royalties should be set at 3% for those holding large‐scale mining licences, the rate negotiated by most mining companies was 0.6% of the gross revenue of minerals produced. The agreements also allowed companies to avoid paying a good deal of corporate tax by carrying forward losses for periods of between 15 and 20 years on a ‘first‐in, first‐out’ basis, meaning that losses made in the first year of operations and the subsequent investment in the later years, could be subtracted in subsequent years from taxable profits.c5d3f9e282e6

The lack of tax revenue from the mining industry and low employment levels became important rallying points for opposition parties in the 2000s. Political pressures amid record-high copper prices resulted in the abrogation of the Development Agreements and a new mining fiscal regime in 2008.f7e89e050f04

Crucially, privatisation brought a new variety of mining companies and capital, ranging from Canadian-registered companies, such as First Quantum Minerals (FQM) and Barrick Mining Corporation, to Chinese state-owned mining companies. Regulating and negotiating with the sector became increasingly complex and required more capacity than dealing with two companies during the colonial and early post-colonial era and one Zambian-owned state company when the mining companies were nationalised. Historically, Zambia has seen a high turnover of political parties representing diverse ideologies ranging from nationalistic to business-friendly postures. As we detail below, intense political competition has caused unpredictability in policymaking and reduced the length of the policy horizon, which has proved unproductive and inefficient and has negatively impacted actors in the mining sector.

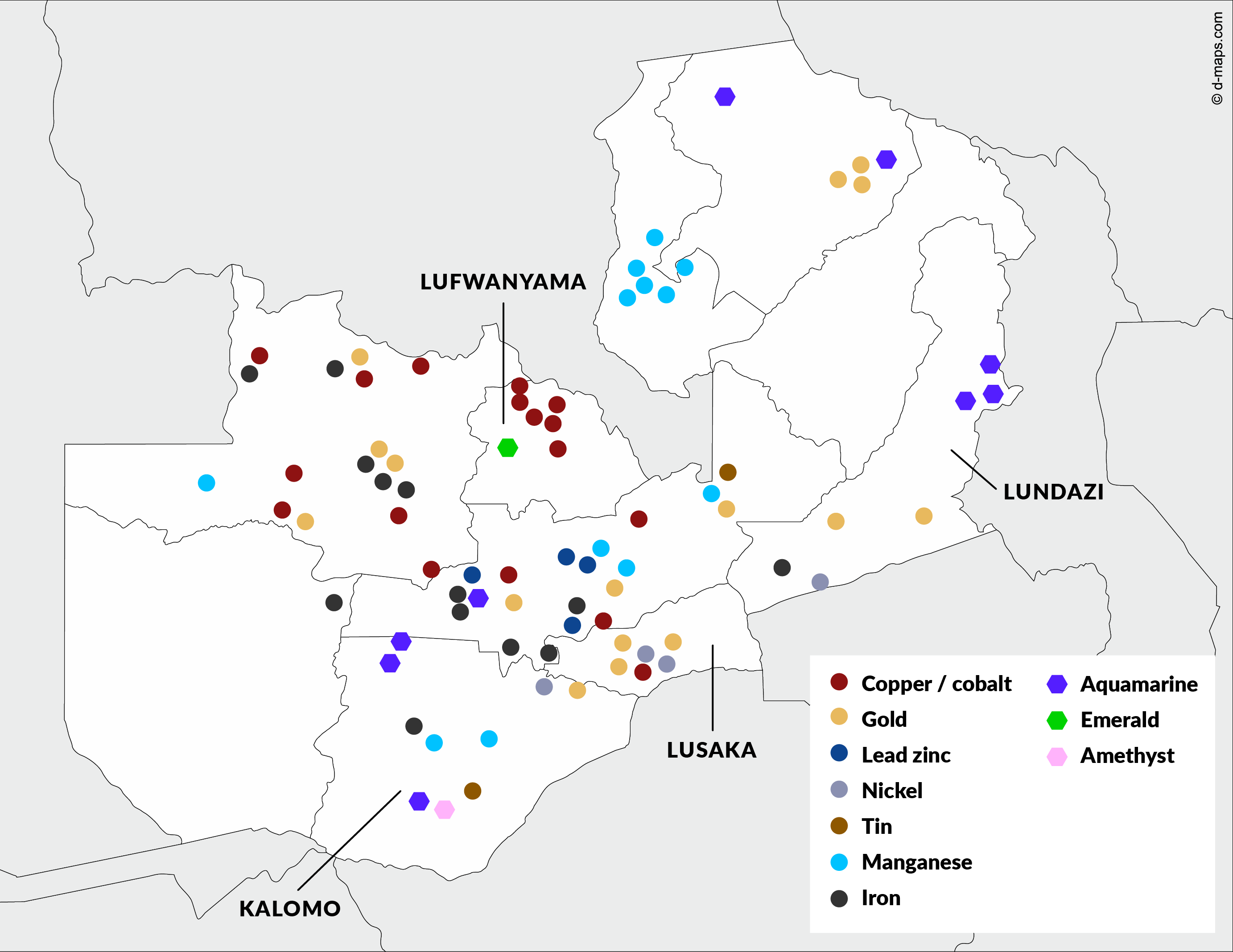

The heightened interest in Zambia’s copper industry following the international rush for critical minerals will exacerbate the abovementioned dynamics. Geopolitical competition has new players vying for a strong foothold in the critical minerals market. The rapid and unregulated expansion of the artisanal small-scale mining (ASM) sector is a relatively new dynamic. While the ASM sector in Zambia can play a crucial role in diversifying the country’s mining industry and empowering local communities, including women and youth, it remains largely an informal and unregulated sector. In 2023, the Zambian Cabinet defined critical minerals such as copper, cobalt, lithium, tin, graphite, coltan, manganese, REEs, gold, sugilite, emerald and diamond as strategic minerals, many of them being in the ASM sector.55c87a7862e3 Unlike copper, these minerals are found in most provinces in Zambia (see Map 1).

Map 1: Distribution of gemstones and selected minerals in Zambia

Source: International Growth Centre (IGC) report (IGC 2019)

Given that the large copper mines are foreign owned, ASM, which requires citizen ownership, has been regarded as a potential avenue for local empowerment. However, since Zambia’s independence, ASM has historically lacked state support, and the policy frameworks have always been skewed in favour of large-scale copper mining.d98f646edef9 Successive governments have prioritised large-scale foreign investment, which was more easily monitored and taxed, instead of ASM, which was considered largely illegal and difficult to regulate.d0f7060161c5 ASM is associated with illegal value chains, environmental damage and exploitation.* ASM is deeply politicised, but unlike the large-scale mining sector, the power play acts out differently as it does not necessarily involve the State House. Instead, it plays out at the level of the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Development (including the MRC) and at the subnational level, where it commonly involves ministers (who are local MPs), local branches of the ruling political parties, with connections to local and international businesspeople. The pattern has changed somewhat since the United Party for National Development (UPND) came into power in 2021, as it is attempting to centralise ASM at the subnational level by introducing marketing boards. The UPND has also introduced cooperatives for local communities to participate in ASM meaningfully. Since this is a relatively new development, it is not yet clear whether this model will be effective for the communities involved.

The urban Copperbelt area has never been the electoral stronghold of the current ruling party, the UPND, even though they made some significant inroads to the region during the 2021 elections. The Copperbelt will see intense political competition in the run up to the 2026 elections. In turn, this will influence some of the policymaking decisions in the next period.

Legal and policy landscape

The above contextual framework sets the backdrop of what now follows: a brief descriptive mapping of the regulatory pillars of the critical mining sector in Zambia and an introduction to the key public actors that oversee and manage the sector. This mapping provides the necessary context for the corruption risk analysis that follows.

Regulatory framework

The primary law governing the sector is the Mines and Minerals Development Act No. 11 of 2015 (MMDA) and its 2016 amendment.a11646b12bb3 The Act regulates the award of mining rights and the management of mining operations. There are two ‘gateways’ to mining rights in Zambia. The first (and most common) is lodging a mining licence application at the Mining Cadastre office. The second is through bidding for mining rights. The bidding process is initiated by the government and typically concerns pre-identified areas of mineral resources. As to the type of mining companies and their scale of operations, the Mining Act provides for artisanal mining, small-scale mining and large-scale mining. Zambian citizens, or a ‘co-operative wholly composed’ of Zambian citizens are eligible for artisanal licences, while ‘citizen owned, citizen-influenced or citizen-empowered’ companies are eligible for small-scale licences. There are no citizenship restrictions on large-scale mining licences.

Section 119 of the Act empowers the minister of Mines to make regulations, also known as ‘statutory instruments’, ‘for the better carrying out’ of the Act. These regulations can cover a broad range of issues, including mineral classification, health and safety, decommissioning and closing of mines, the development of local communities, and the avoidance of wasteful mining practices.An important regulation issued under the MMDA is the ‘local content’ regulation (2020), which seeks to advance local empowerment in the sector by mandating technology transfer, social development initiatives, and the prioritisation of Zambian citizens in the employment and procurement activities of the sector.

Beyond the primary statute and the regulations made under it, there are several ancillary pieces of legislation that affect the mining industry and canvass various issues including environmental protection, citizens economic empowerment, arbitration, taxation, workers compensation, and health and safety. Judicial decisions made by Zambian courts also regulate the sector. As a common law jurisdiction, the interpretation of the law by superior courts is binding. In the mining sector, therefore, judicial interpretations of the statutes and regulations that touch on mining are authoritative.

Finally, government policies and strategies establishing priorities and action plans form a key part of the regulatory regime for the sector. Key objectives of the Zambian government vis-à-vis the mining sector include enhancing geological mapping and mineral resource exploration; enhancing the efficiency, effectiveness and transparency in the management and issuance of mining licences; enhancing the monitoring of operations and compliance in mining and non-mining rights areas; facilitating the formulation of a consultative, competitive and sustainable mining tax regime; and strengthening collaborative research and development in the mining sector.

The key policy isthe Mineral Resources Development Policy (MRDP) of 2022, which sets out the government’s visionfor the sector and the Critical Minerals Strategy of 2024.The MRDP policy promotes value addition, local beneficiation and job creation. It emphasises strengthening the regulatory and institutional frameworks to ensure the mining sector operates transparently and efficiently, focusing on maximising the benefits from mineral resources for the Zambian people. The policy also prioritises the diversification of the economy through the development of non-traditional minerals and supports the integration of local communities into the mining value chain.

The Critical Minerals Strategy aims to harness the country’s abundant mineral resources to drive sustainable economic growth and position Zambia as a key player in the global energy transition. Key components of the strategy include high-resolution geophysical mapping, establishment of a state investment company to hold at least 30% in critical minerals production from future mining projects, promotion of local content and international partnerships to enhance its position in the global minerals market.

Institutional framework

Zambia’s mining sector is administered by the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Development led by a cabinet minister appointed by the president. Directly below the minister is the permanent secretary, who is also appointed by the president and is the chief civil servant for the ministry.

The Ministry of Mines has four key departments: Mines and Development, Mines Safety, Geological Survey, and Mining Cadastre. These departments, and their respective directors, are empowered to oversee and manage the sector. Two committees – the Mining Licensing Committee and the Technical Committee, consider and determine mining rights applications. Another Committee – the Environmental Protection Fund (EPF) Committee – manages the environmental fund set up by the Act to mitigate environmental harm caused by mining activities. A Mining Appeals Tribunal exercises appellate authority over decisions made by the minister of Mines.

The fiscal regime

Critical mineral mining in Zambia is of two orders: large scale and artisanal and small scale.Taxation of large-scale mining operations is based on a two-tier system: mineral royalty tax (MRT) and corporate tax. MRT is based on production and is a percentage of the norm value of base metals produced or recoverable.6db5da713d5a The statute defines gross value as the realised price for a sale free on board at the point of export from Zambia or point of delivery within Zambia. Corporate tax on income from mining operations is 30% (MRT is deductible). ASM operators are charged a 4% presumptive tax on their gross turnover (minus any mineral royalty paid).

Corruption risk analysis: Hazards and loopholes along the critical mineral value chain

We now turn to the regulatory weaknesses and loopholes that facilitate corruption in Zambia’s CMVCs.6a330dcd94d9 The corruption risks explored in this section are synthesised from a law and policy review and from key informant interviews with industry, civil society, public administration and State House representatives.

Inadequate regulatory and governance framework of the licensing process

A significant corruption risk in Zambia’s CMVC is the lack of a transparent, coherent and disciplined mining licensing system. Stakeholders state that illegally obtained licences are frequent.abd1e030885e Externalised pecuniary benefits and financial flows from mining activities from illegally obtained licences constitute an important form of IFFs.

The Mining Cadastre

At the centre of the mining licensing framework is the Mining Cadastre. The Cadastre is the central administrative office that processes mining licence applications and has long been a hotbed of corruption.191585d213d3 The numerous governance challenges at the unit led to its eight-month closure soon after the 2021 change of government. The stated goal of the closure was to identify and root out corrupt elements and practices. The Cadastre reopened in 2022, and while measures were put in place to reduce malfeasance, significant governance vulnerabilities remain.

A key area of vulnerability at the Cadastre is the human element of the licensing application process. Mining rights in Zambia are awarded on a ‘first come, first served’ basis. That is, where more than one person or entity applies for a mining right over the same area of land, the first to lodge the application must be awarded the right, provided all requirements are met.

When mining licence applications are received by Cadastre officials, the officials must determine whether the applications meet the minimum requirements from the Mining Act. If they do, the applications are forwarded to the Mining Licensing Committee (MLC) for consideration. Cadastre officials must also meticulously preserve the order in which applications are received. Stakeholders report that this determinative process,and the preservation of application order, are notable corruption junctures.

The processing system at the Cadastre is a hybrid system with manual and electronic components. The human element, particularly, makes the system vulnerable to corrupt elements. According to our informants, the corrupt schemes most prevalent at the Cadastre include ‘losing’ applications, crippling applications by pulling out vital documents and rendering them incomplete, illegally cancelling licences to make space for new ones,7bcdc78aa95c issuing a single individual/entity with an unreasonably high number of mining licences (up to 50 in one case), taking directives from political cadres/actors, and reserving spots to manipulate the application order and thus circumvent the first come, first served principle.

Further complicating this challenge of corruption, are the severe resource and capacity deficits that hamper operations at the Cadastre. The Cadastre is severely underfunded, and staff shortages and competency gaps have caused major inefficiencies. These gaps foster an environment in which corruption can thrive as licence applicants willing to engage in bribery to ‘move along’ applications are prioritised.

Discretionary decision-making: The MLC

Once the Cadastre completes the iterative process and forwards qualifying applications to the MLC, governance challenges remain. The Mining Act established the MLC to consider and determine applications for mining licences. While the composition of the MLC is prescribed by the Mining Act, a notable discretionary space is reserved for the minister of Mines. The Act empowers the minister to appoint, to the MLC, one representative from:

[E]ach of the Ministries responsible for – (i) the environment; (ii) land; (iii) finance; and (iv) labour; and (f) a representative of – (i) the Attorney-General; (ii) the Zambia Development Agency; and (iii) the Engineering Institution of Zambia (MMDA).aa7ab24e28cd

There is no guidance as to how the minister must go about selecting these representatives, nor is there any qualification or level of expertise prescribed. By law, the minister could appoint anyone – regardless of skill, expertise, existing conflicts of interests, etc – as long as that person is a representative from an institution prescribed by the Act.

Furthermore, the suitability of the MLC to effectively determine mining licence applications is not entirely clear. For one, when considering whether to grant a mining licence, the Mining Act requires the MLC to consider a broad range of issues including the viability of the applicant’s investment forecast, the financial resources and technical competence of the applicant, and whether the proposed mining programme is an efficient and beneficial use of resources. These complex considerations require specialised expertise and, in some cases, independent investigations. The Mining Act empowers the director of the Cadastre to investigate whether the requirements of this section have been met. However, informants report that the capacity to investigate does not exist, and the MLC must rely on information provided by mining companies to reach a decision. This data gap creates a verification challenge and a governance risk.

Also, while the decision-making process requires specialist knowledge, there is no statutory requirement for expertise in the MLC. The lack of technical capacity to effectively review licences was frequently cited by stakeholders. A 2017 review of the MLC found that the committee considered an average of 70 applications at each two hour and thirty-minute meeting. To reach decisions, there was heavy reliance on ‘case preparations’ by the Cadastre who themselves lack the capacity to evaluate mining licence applications and independently verify documents submitted by mining companies.aad9a714ec42 The inadequate assessment of mining licence applications was confirmed during the review of the MLC, which found that mining right holders were granted licences without meeting the financial, environmental or consent requirements that are statutory prerequisites to obtaining a licence.b58092be779e

Since the MLC operates in an information vacuum, discretion plays a big role in mining licensing decision-making. Broad discretionary spaces around licence issuance are an important corruption juncture, since as informants report, they allow opportunistic actors to short circuit the award process and court influential MLC members.

Opacity around transfers of mining licences

Stakeholders flag the opacity in the transfer process of mining licences as a notable governance risk. The relative ease with which mining right holders can transfer rights means that many of these transfers occur under unclear circumstances. By law, the minister has exclusive authority to authorise the transfer of mining rights and the control of a company that holds mining rights.004142827e1f What is less clear, however, is how this authority is exercised, since the Mining Act does not stipulate what the minister must consider when approving a transfer. The practice of ‘fronting’ – a Zambian entity applying and obtaining a mining right but later ceding control to a foreign entity – was highlighted by stakeholders as rampant. There is currently no statutory requirement that transferees undergo a vetting process.

Non-transparent bidding processes

Corruption in bidding is a potential driver of IFFs in Zambia. The Mining Act establishes an ad hoc committee called the ‘Technical Committee’ to consider bids on pre-identified mineral resources advertised by the government.ae58c4c40cc8 After evaluating and ranking bids, the Technical Committee forwards the highest-ranking bidder to the MLC, which then makes the award. After the award is made, the government and the successful bidder negotiate a contract to govern mining activities under the award.

A corruption risk factor around the bidding process is the inadequate governance framework for the process. The discretionary space the minister of Mines enjoys in constituting the Technical Committee is exceptionally large: The minister has unfettered discretion to constitute the committee.284a963fdff2 While the Mining Act requires the committee to provide a ‘detailed analysis’ of all bids (and this analysis must include consideration of the ‘bidder’s investment and financial plan’), the law does not offer any safeguards against fraudulent misrepresentation, conflicts of interest, and inducement and bribery in the bidding process.75109cb2911c Little is known about how past committees have made their decisions, but the governance risks are plain: There are no internal controls to ensure the neutrality of committee members or the integrity of the bidding process.

Further, the contract negotiations that follow the bidding process are potential hotbeds for corruption. Historically, state-investor negotiations and contracts in Zambia’s mining sector are undisclosed. Without adequate disclosure, stakeholders highlight that asymmetrical and corrupt backdoor negotiations can be used to secure contractual terms and concessions that weaken state capacity to police the illegal movement of capital.

Public-private collusion across value chains

Stakeholders report that there is an intricate web of PEPs doing business with the critical minerals mining sector. This creates a classic, ‘principal-agent problem’, in which those responsible for policing IFFs are direct beneficiaries of IFFs from the sector. Through political connections, mining companies can acquire insider information and backhanded favours across the value chain to facilitate IFFs. Stakeholders reveal that concealing mineral origin and value, misrepresenting mineral reporting and chain of custody, circumventing the monitoring of financial account flows by the Bank of Zambia, and fabricating data to facilitate tax evasion can arise from public-private collusion.

There are important causal links between the weak oversight and monitoring of financial flows from Zambia’s critical mining sector and captured public officials. Where the public functionaries responsible for policing illicit capital flight are corrupt beneficiaries of that flight, they have a vested interest in the selective enforcement of IFF laws.

In Zambia, PEPs thrive because existing conflict-of-interest rules and internal controls within government ministries are inadequate. In particular, potential conflict scenarios are not comprehensively outlined, and robust safeguards and effective disclosure mechanisms are lacking. While ‘integrity committees’ in ministries exist, stakeholders suggest that these are not functioning as they should/could, and the legal framework does not adequately address conflicts. Notwithstanding a statutory prohibition of government officials doing some categories of business with the government,435b7ac5ecd0 no such prohibition exists on doing business with the private sector. Informants share that while the ACC has received credible complaints about government officials supplying mining companies, because this practice is not illegal, it is not possible to prosecute. Further ‘local content’ rulesdfed683e844a which require mining companies to give preferential treatment to local suppliers are also corruption junctures, since there are no controls in place to regulate the participation of PEPs in these businesses.

Abuse of intermediaries and agents

Closely connected to public-private collusion is the issue of third-party agents. Mining companies frequently use intermediaries (also known as ‘fixers’) to perform a range of services, including prospecting for mining opportunities, obtaining mining licences (and related permits and approvals), tax compliance, liability assessments and liaising with government officials.

These agents pose significant corruption risks since they (or their subcontractors) are often public servants in regulatory agencies or, at the very least, politically connected. Stakeholders maintain that the channelling of bribes and kickbacks through intermediaries is a well-known practice in Zambia’s mining sector. Third-party agents are important nodes in IFFs when their ‘services’ extend to concealing illicit flows or preventing punitive action pertaining to these flows. Third-party malfeasance is rampant in the import and export of mineral resources. The Mining Act prohibits the import or export of minerals without a permit from the director of Mines. The director of Mines must issue this permit only after receiving and evaluating a mineral analysis and valuation certificate issued by the director of Geological Survey.f32622a835dd The law prohibits the export of minerals not specified in the valuation certificate. However, stakeholders report that through the work of intermediaries, minerals not specified in valuation certificates are routinely exported through Zambia’s border posts.

Weak regulation of the ASM

ASM activity in the emergent mineral sector is disorganised and largely unregulated. Zambia’s mining sector, traditionally composed of a few large-scale mining companies, now also involves factionalised ASM operatives that have splintered the sector. Although the Mining Act mandates that ASM operators be Zambian citizens,ccf8bd9f339e there is no effective enforcement mechanism. As a result, foreign entities often participate in ASM activities by exploiting opaque ownership structures. The informality of the subsector means that the government cannot account for the removal of minerals from the ground and the country. Porous border posts and data blackholesallow minerals to routinely leave the country illegally and largely unchecked. Since these minerals are unaccounted for, it is impossible to say where proceeds end up.

Political economy assessment

The stakeholder analysis in Annex 1 shows how the different institutions and actors relate to IFFs. Their effectiveness, however, is determined by Zambia’s governance systems. Formal and informal systems determine how mineral resource governance plays out in practice. These dynamics must be considered when designing any intervention in the governance sphere. The overriding element is the historical dominance of the State House and the dominant powers of the presidency, which are a result of Zambia’s constitutional set-up.

A shift from state to market-led economics accompanied the transition from a one-party state to a multi-party democracy in 1991. This led to a broader restructuring and repositioning of Zambia’s economic governance and civil service. However, it did not lessen the executive powers of the presidency. Constitutionally, the president is still in charge of all major appointments (ie state-owned enterprises, statutory bodies, judiciary, speaker of parliament, Electoral Commission of Zambia). This role has historically undermined the principle of separation of power.For example, the president can appoint ministers and unilaterally determine the number of ministries, appoint judges of superior courts, reprieve offenders, nominate (unelected) members of parliament, and dissolve parliament. In relation to the conduct of election, the president had sweeping powers to establish the electoral commission and to directly appoint all the commissioners, including the chairperson. So, despite many political turnovers and constitutional and legal reforms, the political economy environment has not fundamentally changed. The State House is still central in determining priorities and policymaking, notably in the large-scale mining sector. This lack of transparency in deals risks the exploitation of public resources, extraction of rents and undue influence on the decision-making process. Moreover, political interference in civil service, regulatory bodies and statutory bodies risks undermining the effectiveness of these institutions.

When it comes to the mining sector, the State House’s central role in decision-making and facilitating large mining contracts risks undermining the role of existing ministries and regulatory institutions. One of the consequences is insufficient investment in the creation of independent and professional institutions. With political interference, many professional board members opt to leave to maintain their reputation. The resignation of the chair of the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Limited (now ZCCM Investments Holdings [ZCCM-IH]) board in May 2023, who reportedly complained about interference from the State House in their functioning, is a point in case.906ca428f3a0

The central role of the State House also threatens to undermine accountability mechanisms, as the state’s dealings are not in the public sphere. Companies that, from the onset, have the support of the State House tend to overrule all other regulatory bodies, such as the MLC, and are less likely to comply with other regulations, such as the Zambia Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA), etc. Facilitating access to the president, notably through State House advisers, also carries the risk of corruption. Another governance risk of the central role of the State House is that it takes on many tasks and loses focus.

The executive nature of Zambia’s presidency also impacts the anti-corruption agencies. The independence of the ACC is undermined by the president appointing the director general (DG) and the board members, a provision that was made in the 2016 amended constitution. In July 2024, a whistleblower within the ACC board revealed that the DG was failing to prosecute politically connected individuals.f6b87640f4ba While the DG was forced to resign, the ACC board was dismissed. In January 2025, the president appointed a new DG and board, but this has not resolved the fundamental problem of the lack of institutional independence of the ACC. The latest report by the FIC, a Zambian agency that deals with IFFs relating to money laundering, showed that corruption and illicit flows are still prevalent.ae1512ee3d93

The central role of the State House in mining deals also poses a risk to tax collection. The support of mining companies for presidential candidates and their political parties translates into an exchange of favours realised after elections. An historical example is that following President Sata’s death in October 2014, mining tax rates were immediately renegotiated; this was repeated in 2016 and 2021 and points tonegotiations and business influence over the State House.9ebed501f60c

While the ZRA has been a semi-autonomous institution since 1994, the president limits the autonomy of the ZRA by directly appointing its DG. While it has not reached its full potential, the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development rates ZRA’s professionalism as high as that of other regional revenue authorities. While Zambia’s overall tax effort (tax-to-GDP ratio) was slightly above the average of the African Tax Administration Forum’s 37 member states in 2017, the ZRA ranked fourth for revenue productivity, which is revenue per tax employee, making it one of the more efficient tax authorities on the continent.f8e52b51381c The mining tax unit was established in late 2009, was located within the large taxpayer office (LTO) and helped to specialise ZRA personnel in mining tax administration further.

According to our informants, ZRA has been able to carry out audits of high-profile mining companies without political interference.c4c2865063ec However, the blind-spot for investigations is with non-high-profile companies. This was highlighted recently in a statement by the ZRA DG, who disclosed that only six mining companies out of 6,000 that hold mining licences in Zambia pay tax.53fe263413d8

In addition, there has been a risk with the role of tax consultants with direct or indirect links to ZRA providing advice to mining companies. Some private companies operate as private consulting firms, and lawyers or accounting consultants are linked to actual or former ZRA public officials, which is a clear conflict of interest. They offer consulting services to private companies to understand how to reduce taxable income. They also assist mining companies in negotiating reductions in their tax bill with ZRA. In return, they get a kick-back paid into an offshore account (eg Dubai or South Africa). According to the IMF, ZRA has a sound anti-corruption framework, but implementation is sometimes lacking.6de00237da37 The VAT refund mechanism creates the potential for discretionary decisions, as companies can pressure ZRA for preferential treatment to get their refunds. During the second quarter of 2022, FQM reached an agreement with the Government of Zambia for repayment of the outstanding VAT claims based on offsets against future corporate income tax and MRT payments.855940d75f69

The ACC also indicated the challenge of ‘missing minerals’ through the manipulation of certifications and documents. In particular, the role of clearing agents and freight forwarders is to place goods on airplanes or in boxes such that it is more difficult for authorities to control the content. This is a strategy that is used to conceal goods and avoid control and monitoring processes.

The risk of having a close relationship between regulators and mining companies is that the mineral tax regime can be too lenient. As one informant put it,

It seems that tax policy is on the advice of mining companies and as a reactive measure rather than evidence-based. Clearly, the decisions were made on promises made to the mining companies.

However, the situation can change rapidly when governments are fiscally constrained and face political competition. The current stand-off between the government and mining companies regarding the new legislation, which shows signs of recurrence of a resource-nationalist approach that started in the 2010s, will demonstrate if large-scale mining companies still have the same influence they had right after the elections.1ad7d19b97b6 Presumably adapting to the new situation, FQM has now entered into a voluntary agreement on local content after actively resisting this policy for decades.aa4de06ad302

Overall, the alternation in power of different political ideas, from nationalistic to business-friendly, has generated volatility in the policymaking framework. Frequent political turnovers reduce the length of the policy horizon. This, in turn, generates uncertainty among public and private actors operating under changing circumstances – a problem given that the proper management of the mining sector calls for long-term decisions.01bdd3054578 The net result of these negotiations and reversals is an irregular, untransparent policymaking process, which has led to an unpredictable tax regime unfavourable to all stakeholders, hampering administration for tax authorities.

In parallel with continued executive powers, patronage relationships and rent-seeking behaviours have become more decentralised and shifted to local government and bureaucratic levels.bd4425bb2733 While high-level decisions – such as those concerning large mining companies and mines – have remained within the sphere of influence of the State House, local power relations between business interests and low-level bureaucrats and politicians have characterised smaller-scale business activities. The decentralisation of the patronage mechanisms has affected the rapidly growing ASM sector. Local politicians and businesspeople participate in this smaller, less capital-intensive segment of the mining sector.e4c2889572a9

Because many of the smaller ASM companies are established by disadvantaged individuals, such as women or youths, who have a lack of capital and are disconnected from the value chain, they struggle in a subsistence mode. Consequently, they are at risk of being drawn into illicit activities. While the legal framework incentivises the ‘Zambianisation’ of the ASM sector to develop a class of local entrepreneurs, this process has incentivised fronting, where Zambians act as fronts for foreign investors coming from, among other places, South Africa, India and China. Recent research shows that Chinese capital is behind small and artisanal mining companies fronted by Zambian nationals and involved in unregulated mining activities and transnational smuggling of copper, gold, lithium and cobalt. There are also indications that Chinese nationals operate small mines and refineries in the Black Mountain area.a3890085b7ae

In many cases, small-scale mining companies do not pay taxes. ASM outfits can be physical rather than legal entities with no corporate structure. There is evidence of companies using personal accounts for business, affecting the accuracy of business records and tax compliance. They often have no physical or email address, headquarters or phone numbers.f5aa7bdabb20 The informal networks between local public officials and small and artisanal companies allow local politicians and low-ranking public officials to manage companies that can supply goods and services to mining enterprises, such as transportation, logistics or security services. While there is a repeated call to formalise the ASM sector, it is difficult to enforce if local politicians and authorities benefit from informal arrangements. The Zambia Chamber of Mines has expressed concern about the informal nature and potential criminalisation of ASM. They point out that this development negatively impacts agriculture, increases the likelihood of gendered violence and has environmental consequences. Crucially, for their own investments, they fear the encroachment of this sector on formal mining sites.

Foreign capital dominates the private sector. The interests and agendas of international private sector actors – such as multinational corporations and venture capital firms – influence domestic political dynamics. As evidenced by interviews and document analyses, efforts have been made to support politicians and political parties with a more business-friendly stance and to oppose those proposing nationalist policies.410e2c092565 Interaction between the Zambian government and international companies can impact the flow of capital and investment entering and leaving the country.

Leehas shown that the Chinese approach to mining in Zambia is different from Western-type investment.a29ea7d97b2c Chinese mining firms continuously operate, even when copper prices are depressed. Previously, Chinese firms have shown resilience by increasing investments when copper prices are low and other firms decrease production, labour and investment. For instance, the China Nonferrous Mining Corporation (CNMC) incorporated the Luanshya mine and Jinchuan Group acquired Albidon Ltd at a time when Western companies were pulling out of Zambia’s extractive industry. Chinese firms also take advantage of economic and business cycles to pick up unattractive assets that Western capital investors lack the courage to acquire and assets that seem unattractive during economic busts, which is attractive to governments seeking long-term stability. However, Chinese investment in Zambia is still a subject of ongoing scrutiny. Reports of labour violations and environmental regulations taint Chinese investment in Zambia. Although there have been reports of labour rights and laws being violated by large-scale Chinese firms, many of these reports concern small- and medium-scale mining companies. Unlike big investments, small mining companies are neglected and unregulated by the Chinese government.973226442788

There are also new players in the game, such as the Gulf states, most notably the United Arab Emirates (UAE), who are starting to invest in mining and infrastructure in Africa. As Opalo (2024) has noted, the current multipolar moment presents African states with unique opportunities to negotiate their way out of the global economic and geopolitical periphery but also brings many risks. Opalo notes that African elites see Gulf economies as places to store or hide their wealth safely rather than as commercial centres. The UAE’s latest forays into mining, renewables and the green economy in Africa is through involvement in carbon trading, procurement of critical minerals and buying stakes in mining companies. Opacity and illicit deals permeate these ventures through which they can reroute cash to amplify and obfuscate BO of investments back home.3ecbe054d6d6

Looking ahead: Reforms and interventions

A few cross-cutting challenges pervade the anti-corruption and anti-IFF intervention landscape. First, the rapid fragmentation of the mining sector is testing the adaptive ability of intervention efforts. Historically, mining in Zambia has been the preserve of a few large players focused on copper mining. This is no longer the case, and the sector has become more fractured and complex. New minerals are being discovered and mined, and ASM is proliferating. Interventions that focus exclusively on the copper value chain and large-scale mining projects are no longer adequate. Also fragmented is the legal and institutional framework around corruption and IFFs; while there are various laws, policies, and institutions that deal with varying aspects of the challenges, there is a lack of coordination in the architecture. Further, implementing actors are uncoordinated. Civil society in Zambia is generally fragmented and uncoordinated, and cooperating partners have their own geopolitical considerations to consider when deciding how to intervene in the sector.

These challenges notwithstanding, there are still some suitable entry points for governance interventions supported by reliable allies and cooperating partners in the following areas.

Enhanced systems for disclosure and due diligence

Zambia is a member of the EITI (in this context, ZEITI). ZEITI is administered by a multi-stakeholder group and is hosted by the Ministry of Mines. ZEITI contributes to local discourse on mining fiscal regimes and domestic resource mobilisation, and it provides data to inform regulatory reform and benefit sharing. It also trains government officials and other stakeholders on accessing and using disclosure information.

ZEITI’s most significant intervention is around BO. ZEITI operates a mining licence register and supported the establishment of a BO register at the Patents and Companies Registration Agency (PACRA). BO information plays an important role in mitigating IFFs from the sector. Informants report that publicly available BO information is regularly used by the FIC to identify the true owners of companies under investigation. This information often unmasks foreign nationals as the true owners of companies fronted by Zambian nationals. Similarly, companies operating in Zambia also use BO information to conduct due diligence and eliminate corruption.

Despite these gains, challenges in BO implementation remain. For one, compliance levels are still very low, giving PEPs and their conduits ample opportunity to obfuscate ownership structures and engage in illicit fund transfers.501d5df16b4d Further, current BO protocols do not mandate disclosure around PEPs. Also, while BO frameworks can be an ‘easy sell’ to governments looking to improve their foreign direct investment prospects, a significant challenge that affects the delivery of an efficient and effective BO system in Zambia (and elsewhere in the region) is the lack of ‘buy-in’ from the private sector. Private actors often don’t see the value in BO initiatives and view BO reporting requirements as an additional administrative burden.

Intervention efforts around disclosure that prioritise private sector engagement, establish frameworks and tools for the disclosure of PEP participation in the mining sector, and enhance compliance with existing BO protocols can be useful.

Support for ongoing reform of the Mining Cadastre

As explained earlier in the report, the Mining Cadastre was closed to the public in 2021 to address corrupt practices. Since the Cadastre’s reopening in November 2022, the government has embarked on an ambitious reform programme, which includes replacing senior staff with new officers, clearing all backlogs, digitising the application process to remove the human interface and reduce corruption and inefficiency, and publishing MLC decisions on the Ministry of Mines website to increase transparency.fa1b5337e8c6 If effectively implemented, these initiatives can enhance the mining licensing regime. However, the severe capacity and resource deficits that drive inefficiency (discussed in the corruption risk analysis above) may hamper the effectiveness of these efforts since inefficiency drives corruption. Technical assistance from cooperating partners to upgrade operations and promote efficiency may help reduce corrupt exchanges.

Support for evidence-based policymaking

Intervention programmes should anticipate political economy realities in programming. Political calculations often override sound policymaking. Cash-strapped governments tend to make short-term resource allocation decisions to court voters, turning a blind eye to corrupt elements within the government if politically expedient.

Partners can mobilise the current political will for evidence-based policymaking, which is slowly being integrated into the ministries (ie through monitoring and evaluation units). While there appears to have been resistance to efforts by the State House to promote evidence-based decision-making, this practice is slowly becoming entrenched. The Presidential Delivery Unit (PDU) and Public Private Dialogue Forum (PPDF) are central actors in this process and enjoy the highest level of influence at the State House.

Support for organisation of ASM sector

Under the current UPND government, there has been a renewed commitment to developing ASM. One of the objectives of the 2022 National Minerals Resources Development Policy is to ‘[f]acilitate the development and growth of the Artisanal and Small-scale Mining subsector in order to enhance its contribution to economic development and wealth creation.’65711f0994a6 As mentioned earlier, however, ASM is disorganised and largely unregulated. The risk of further (international) criminalisation will largely be at the expense of local communities and ZRA’s ability to collect revenue from the sector.

The UPND government has been drafting the Geological and Minerals Development Bill. The draft version contains a strategy to formalise the ASM sector and establish an Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Fund to serve as a credit facility for its development. President Hichilema’s cabinet also approved the integrated ASM marketing model in 2022. This model includes forming ASM cooperatives, increasing capacity of those cooperatives and providing marketing arrangements for ASM operators. While most ASM operators will likely welcome the provision of marketing arrangements, some analysts have questioned the viability and usefulness of ASM cooperatives (or ‘rural producer organisations’). These critics maintain that ASM cooperatives tend to be overly reliant on external assistance, possess weak internal governance and accountability structures, and provide minimal benefits to their members.2dc27c499032

Enhancing the quality of civil society organisation public discourse

Like many institutions in Zambia, civil society organisations (CSOs) suffer from information asymmetry in the mining sector. However, fully utilised existing information can challenge issues related to mining governance. For example, ZEITI has large databases on the mining sector, but so far, CSOs and think tanks have not used them as a source for analysis, policy advice and advocacy. Linkages between research institutions and CSOs could potentially advance the technical knowledge necessary to deal with this sector.

CSOs often focus on the government or mining companies. However, they should also direct their activism towards professional bodies like the Law Association of Zambia. The activities of professional and semi-professional intermediaries are critical to bridging business, bureaucratic and political interests. Law and accounting firms are well-known conduits for corruption-related IFFs.da2833ff6c6a Moreover, CSOs can influence the discourse on geopolitical strategies by promoting ideas that leverage Zambia’s position, like the soon-to-be-established transport corridors.2d5e9129dd17

Enhanced collaboration in anti-corruption agencies

The ACC’s efforts have been severely undermined on the technical and governance levels. As outlined earlier, several loopholes in the anti-IFF architecture exist. Interventions are necessary to enhance communication, cooperation and collaboration between various anti-corruption institutions in the mineral management regime. Further, interventions that improve the transparency, accountability and business integrity of state-owned enterprises could also be useful. Greater coordination and information sharing in the governance architecture is also required. Anti-money laundering institutions must be strengthened through investments in digital systems and early warning systems for IFFs.

Conclusion

Zambia sits at the cross-roads of a strategic opportunity to harness its critical minerals for meaningful development. However, to do so, Zambia must overcome the numerous governance weaknesses that facilitate corruption and IFFs from the sector. While the intervention landscape has its challenges, this Issue has identified governance interventions that can support Zambia in its efforts to curtail corruption and IFFs and position itself to benefit from the geopolitical competition of the green energy transition. However, these initiatives must be designed with the appropriate political economy context in mind. As political actors look towards the next election (in 2026), the length of the policy horizon in highly contested sectors like mining may be truncated, and political expediency may affect the implementation of partnership strategies and agreements. Governance interventions must not underestimate these political pressures.

Annex I

|

|

Roles and responsibilities |

Informal activities and tacit influences |

|

Public sector |

||

|

State House/ presidency |

The offices of the presidency. The president is the head of state and government. Appoints public officials, including ministers, to help execute its duties. The president and State House have no formally legislated role in mining. |

The State House has both a direct and indirect influence on the sector. The direct influence is usually through formal engagements with mining stakeholders, and the indirect influence is through presidential appointments in state agencies and enterprises. |

|

Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development (MMMD) |

Formally responsible for the management of the mining sector. The ministry has four operational departments: Mining Cadastre, Geological Survey, Mines Safety, and Mines Development. |

The minister has discretion over the ministry’s decisions. The minister can overturn departmental decisions and appoint members of the Mining Appeals Tribunal, who can review their decisions before the compliant can seek remedy from the courts. |

|

Ministry of Finance and National Planning (MoFNP) |

Responsible for fiscal policy, which includes mining taxation. The minister of finance also holds shares on behalf of the government in companies. |

Susceptible to the influence of the State House and mining companies. Tax policy is influenced by the State House, the minister, the mining sector and the political cycle. |

|

ZRA |

The ZRA assesses, charges, levies and collects taxes for the government. |

The agency has structural weaknesses that impact its capacity to effectively and efficiently collect taxes. Over the years, they have built some capacity, but frequent tax policy changes and political interference affect their operations. |

|

ZCCM-IH |

ZCCM-IH is an investment holding company with shares in various mining firms and other entities. The Zambian government is the largest shareholder in the company. |

The informal structure is centred at the State House. The president is the chairperson of the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) board. The State House, MMMD and MoFNP interfere in company operations. |

|

ZEMA |

Government agency responsible for environmental management. Approves environmental social impact assessment of mining and other projects. Develops and enforces laws that prevent and control pollution. |

Like other agencies, it is vulnerable to political interference. It has inadequate financial support, technical capacities and skilled human resources, which limits its ability to effectively monitor and observe mining operations. |

|

FIC |

The FIC in Zambia monitors the mining sector for IFFs and money laundering. |

FIC produces good data, but has no power to prosecute; as such it is dependent on other arms of the government to act. Tracking IFFs across borders can be complex, requiring international cooperation, which may be difficult to achieve. |

|

Ministry of Energy (MOE) |

Management and development of the energy sector. Supervision of the Energy Regulation Board (ERB), Rural Electrification Authority and others. |

Interference from the State House, and the minister has discretionary authority over decisions. Minister vulnerable to political and business interests. |

|

ERB |

Regulation of the energy sector. Reviews and approves prices and tariffs for energy products. |

Interference from the State House and the minister. |

|

Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation (ZESCO) |

Dominates the generation, transmission, distribution and supply of electricity. Supplies electricity to mines, particularly mines on the Copperbelt. |

Used as a special-purpose vehicle for political patronage and funding, which has put ZESCO in a financially unsustainable position and heavily indebted. |

|

Local governments |

Responsible for the provision and policing of various public goods and services. Collects levies from entities, including property rates and others. |

Inadequate financial and technical capacity to ensure the provision of quality public goods and services. Large-scale mining companies are among the most significant contributors to their revenues. |

|

Academic and research institutions |

Provision of skills to the mining industry. Research and development in mining. |

Capacity constraints limit their ability to meet industry demands – limited research funds for independent research. |

|

National Assembly of Zambia (NAZ) |

Provides an oversight role in executive decisions and actions. Approves national budget, debt and the sale of national assets. |

The executive sometimes decides without parliamentary approval. Inadequate institutional capacity to effectively provide oversight. |

|

Traditional authorities |

Custodians of traditional land manage natural resources and regulate and enforce customary laws. |

Mediate between mining firms and communities to ensure the latter benefit from mining. The integrity of the respective chief determines whether the outcome of the negotiations benefit the community or not. |

|

Private stakeholders |

||

|

Large-scale mining firms (Zambia Chamber of Mines) |

Most of the largest mining companies are Western and Chinese. Largest taxpayers and exporters. |

Informal interaction with the State House and public officials. Disputes with the state on tax policy; compliance; and environmental, social and governance irregularities. |

|

Coordinating forums (eg PPDF, PDU and MMMD-ASM) |

Established to facilitate various government objectives – expedite public projects and promote private investments. |

Struggled to obtain legitimacy. Lack of cooperation from public officials. |

|

Mine suppliers and service providers |

Supply goods and services to mining firms. Mines spend more on procurement (US$4–5 billion) than taxation. |

Foreigners dominate the supply of goods and services. PEPs and influential mining companies have frustrated the creation of a local content strategy. |

|

Artisanal and small-scale miners |

ASM is restricted to Zambians. Mainly informal with limited technical and financial capacity. |

Locals act as fronts for foreigners. Exploited by mineral traders. Overlooked in mining policy. |

|

Broader civil society |

Advocates for communities’ improved benefits from mining. |

Inadequate capacity and power disparities with government and mining companies. |

|

Mining-affected communities |

Communities close to the mines are impacted by activities. |

Demand for effective corporate social responsibility (CSR). Mines have an exclusionary approach in CSR planning and implementation. |

- UNCTAD 2023.

- Transparency International 2024.

- National Assembly of Zambia 2023.

- No. 6 of 2018 as amended by No. 6 of 2023.

- No 14 of 2001 as amended by Act No. 44 of 2010.

- CAP 87 of the Laws of Zambia.

- No. 46 of 2010.

- No. 3 of 2012.

- Just after this paper was prepared, a new mining law came into force, viz, the Minerals Regulation Commission Act of 2024, which establishes the Minerals Regulation Commission (MRC) to oversee and regulate the nation’s mineral resources. The analysis in this Issue is based on the repealed Mines and Minerals Development Act of 2015.

- This includes a study SAIPAR conducted with the Basel Institute on Governance focused on risks in the mining sector (Costa, Banda and Hinfelaar 2023).

- Lobito Corridor 2023.

- European Commission 2023.

- IEA 2021.

- Zambia Statistics Agency 2023.

- The world average is 38.33 index points (TheGlobalEconomy.com 2022).

- World Bank Group 2024.

- For details on the nationalisation process see Lungu 2008a.

- For further reading see Lungu 2008b.

- Ibid.

- Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development 2024b.

- Caramento and Siwale-Mulenga 2023.

- Siwale and Siwale 2017.

- Mines and Minerals Development (Amendment) Act No. 14 of 2016.

- The mineral royalty rates are (a) 5% of the norm value of the base metals sold or recoverable under the licence, except when the base metal is copper, cobalt and vanadium; (b) 5% of the gross value of the energy and industrial minerals sold or recoverable under the licence; (c) 6% of the gross value of the gemstones sold or recoverable under the licence; (d) 6% of the norm value of precious metals sold or recoverable under the licence; and (e) 8% of the norm value of cobalt and vanadium sold or recoverable under the licence. Where the base metal sold or recoverable under the licence is copper, the mineral royalty rate payable varies between 4 and 10% depending on the price of copper.

- Risks relating to revenue collection are examined in the political economy assessment.

- As discussed later in this Issue, obtaining a mining licence illegally can occur through several methods, including bribery of government officials, falsification of documents and bypassing established procedures.

- Lusaka Times 2022.

- Since only one licence can occupy a particular area at a time.

- Section 6 of the MMDA.

- Ibid.

- Auditor General’s Office of Zambia 2017.

- Section 66 of the Mines and Minerals Act No. 11 of 2015.

- Ibid, Section 19.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Section 20 (1) (b) of the Mines and Minerals Act No. 11 of 2015 provides that ‘a holder of a mining right or a mineral processing licence shall, in the conduct of mining operations or mineral processing operations and in the purchase, construction, installation and decommissioning of facilities, give preference to contractors, suppliers and service agencies located in Zambia and owned by citizens or citizen-owned companies’ (Zambia 2015).

- See, for example, Section 15 of the Public Procurement Act No. 8 of 2020, which prohibits government officials and their relatives from participating ‘as a bidder in a procurement by a procuring entity by which’ that official is employed and Section 21 Anti-Corruption Act No. 3 of 2012, which provides that an offence is committed by a public officer who uses their ‘position, office or authority or any information that the public officer obtains as a result of, or in the course of, the performance of that public officer’s functions to obtain property, profit, an advantage or benefit, directly or indirectly, for oneself or another person’ (Zambia 2020, 2012).

- Ibid, Section 47.

- Ibid, Section 29.

- Sinyangwe 2023.

- Namaiko 2024 and FIC 2024.

- Kaaba 2024.

- Bebbington, et al. (2018) p. 143.

- ATAF 2019.

- Shalubala 2024.

- For an example of an audit see Lusaka Times 2018.

- First Quantum Minerals 2022.

- IMF 2023.

- Zambia Monitor 2024.

- Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development 2024a.

- Manley 2017.

- Makanday 2024.

- Bebbington et al 2018.

- Southern Africa Resource Watch 2024.

- FIC 2018.

- Costa, Banda and Hinfelaar 2023.

- Li 2010.

- Lee 2017.

- Opalo 2024.

- IMF 2023.

- Statement by Ministry of Mines permanent secretary, May 2023.

- Zambia 2022: 9.

- Siwale 2018.

- Devermont 2024.

- FIC reports 2018 and 2024.