1. Into the ‘vicious cycle’

Violent conflict and corruption can cause and exacerbate each other. The likelihood of violent conflict increases when corruption goes unchecked and injustice is widespread. Violent conflict, in turn, often creates the enabling environment for corruption.62eb9e81277a Together these processes create a vicious cycle. The experiences of ‘post-conflict’ reconstruction and state building, in contexts as varied as Sierra Leone and Liberia, Southeast Europe, Iraq, Afghanistan, Colombia, and Guatemala, have shown the far-reaching negative effects of corruption: it disrupts livelihoods, undermines trust, fuels lingering grievances, and can sabotage peace processes or even trigger violent resistance.bd4aed5f9a7d Conversely, there is evidence that lower levels of corruption may actually help to achieve durable peace.ea342db79139

Two decades of academic literature and evaluations of peacebuilding practice have consistently stressed the destabilising effects of corruption and lamented the failure to tackle them. Peak interest in this discussion has coincided with major crises in post-war contexts such as Liberia, the Balkans, Iraq, and Afghanistan, yet interest has waned each time and little has been done to change peacebuilding practice. Peacebuilders have been reluctant to proactively embrace the issue of corruption for a number of reasons. Some authors suggest that ‘dirty deals’ are part of the process of peacemaking and need to be tolerated to reduce violence and increase stability.6aeba54f853e Mediators are often concerned that addressing corruption could undermine their delicate relations with key conflict stakeholders. If confronted with an embarrassing topic, they fear, conflict actors could reduce their commitment to the negotiations, or the facilitator could lose their mandate.3be58eab6500 Moreover, the potential for parties to a conflict to weaponise accusations of corruption against their enemies poses risks for mediators, whose access depends on being perceived as impartial.a5f659f36b93

The governance and anti-corruption communities, for their part, have gradually begun to develop a conflict-sensitive understanding of how anti-corruption measures can contribute to — or undermine — peace and reconstruction processes, and how insensitively applied anti-corruption measures might destabilise post-conflict contexts.4133d9eef91f However, they still often prioritise technical solutions and shy away from dialogues and negotiations that are perceived as political. They have not necessarily acted upon the advice to think about such issues early, well before post-conflict development assistance comes into play. These considerations have led to a de facto division of labour and sequencing: mediators first aim to end violence and reach a peace agreement, while anti-corruption actors come in later to address issues of accountability and governance.

The aim of this U4 Issue is to question this sequencing and division of labour and to insist on the value of engaging peacebuilding and anti-corruption organisations in an open dialogue about shared priorities. We do not aim to provide a blueprint for action, but seek to open the doors for further dialogue and interaction between two communities of practice that have often worked side by side but not necessarily together. By highlighting the commonalities and differences among these two communities and their approaches, we hope to break down silos and identify entry points for enhancing transparency, accountability, and integrity while supporting peace processes. Corruption must be put on the agenda of peace and transition processes in ways that do not undermine fragile political settlements but strengthen inclusive governance and harness the energy of non-violent protest movements.d8786a541824

Moreover, approaching peacebuilding and anti-corruption measures in tandem makes sense as both attempt to change the conditions and attitudes that engender exclusion and injustice. Accordingly, a successful integration of the two approaches may be the only way to realise a truly inclusive and just peace. This contrasts to a negative peace ‘of the few’, built on exclusive elite settlements and abuse of power and interconnected with organised crime and illicit economies.a96cbf3eefb2 Reducing corruption, like building peace, is a long-term political contest during which setbacks are frequent and successes are hard fought and uncertain.2e5f896a27e8 Charting this difficult terrain requires reflection, learning, and space for confidential and constructive dialogue between anti-corruption and peacebuilding communities. Both communities can and should do more to empower local actors, including by incorporating a democratic anti-corruption agenda.

A significant literature focuses on corruption in fragile contexts. This U4 Issue, however, emphasises the connections between corruption and violent conflict. In particular, it considers how to integrate corruption in peace talks and dialogue processes within a multi-track approach. It emphasises the need to engage all conflict stakeholders, including state and non-state armed actors, in thinking about anti-corruption.

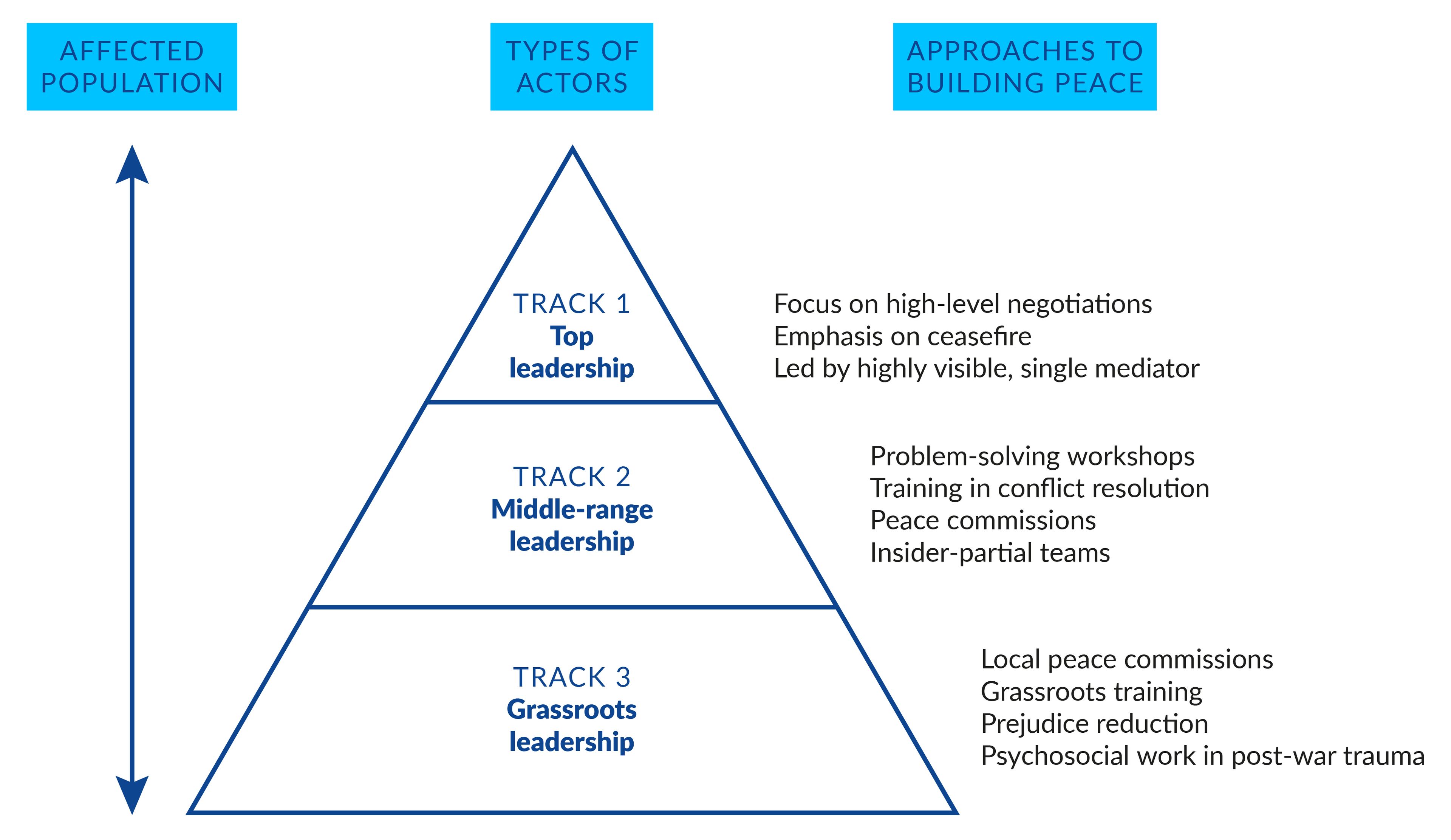

Section 2 reviews existing research on the systemic linkages between corruption and violent conflict. In section 3, inspired by the language of conflict sensitivity and particularly the idea of ‘working in’ conflict, we discuss how to ‘work in’ corruption. We emphasise the need to understand the destabilising effects of corruption in peace processes and to be ‘corruption-sensitive’ as well as conflict-sensitive in designing interventions. Section 4 collects ideas for integrating anti-corruption in peacebuilding efforts along the three ‘tracks’ of mediation introduced by John Paul Lederach in 1997, corresponding roughly to top-level national leadership (track 1), mid-level or regional leadership (track 2), and the grassroots level (track 3). This allows us to identify entry points for involving different societal actors at all stages of violent conflict. A brief conclusion suggests next steps.

2. Using a systems approach

An understanding of the systemic links between corruption and violent conflict provides a foundation for integrated approaches to addressing both. The detrimental impact of corruption on fragility and violent conflict as well as on statebuilding and peacebuilding is well established. Corruption is both an underlying cause and a driver of conflict and violence, and it can undermine a peace process if not addressed.5b276cbc4e20 Highly corrupt states are more likely to be fragile states,43064117bd34 and popular perceptions of high levels of corruption are likely to exacerbate conflict over the long term.

In the short term, however, corruption can sometimes serve to defuse conflict dynamics.714a77dcbdfb Cheng and Zaum suggest that corruption has a differential impact on conflict over time. Initially it can play a stabilising role in ending violence and cementing peace. In the post-conflict period, the redistributive effects of corruption may also be stabilising. In the long term, corruption has corrosive effects that are overwhelmingly negative and that damage state legitimacy and collective trust.db68e3017d5f

The concept of ‘elite bargains’ or ‘political settlements’ helps us understand how political orders are stabilised by elite deals that governing the distribution of economic opportunities among members of the elite.69a55cccac2e By ensuring that actors in a position to seriously destabilise the system have a vested interest in maintaining it – through access to natural resource rents, public tendering, import licences, agriculture boards, customs duties, and other parts of the economy where competition can be managed and large private profits made – such deals ensure the reproduction of the status quo. While such bargains are generally exclusionary, can drive popular grievances, and limit economic growth, they are often successful in reducing intra-elite competition and maydecrease violence as a result. Disruptions to such bargains can, in turn, have destabilising effects.b425559f2867

While the effects of corruption on conflict are discussed at length within governance and statebuilding literatures, less attention has been given to the ways in which violent conflict affects corruption and anti-corruption efforts. Boucher and colleagues suggest that conflict creates a climate for corruption by:

- reallocating political and military power from legitimate state actors to non-state actors, thus undermining the state’s monopoly on violence and political participation;

- weakening formal institutions and public administration while strengthening informal rule, thus undermining provision of public services and delegitimising the rule of law;

- enabling and strengthening informal black markets, illicit border trade, and trafficking, thus undermining efforts towards a formal market economy and peace dividend; and

- triggering the influx of external resources for humanitarian assistance, peacebuilding, and post-conflict development assistance, creating new opportunities for rentseeking through ‘wasted, misspent or mistargeted’ support.69ed201450ec

2.1 Introducing systemic thinking

Given the long-term detrimental impact of corruption on conflict and of conflict on corruption, their relationship is often described as a vicious cycle. More accurately, conflict and corruption might be described as interdependent, interconnected elements of a system.

A full development of the systemic relationship between corruption and conflict is beyond the scope of this report. To illustrate key elements of the system, however, let us trace how the relationship might evolve in a fictional place we will call Country X. This simplified model is based on a composite of cases rather than on any particular case.

- Interdependence of corruption and conflict: In Country X, longstanding marginalisation of minority groups and violation of their political and economic rights by elites of the majority population have led to armed resistance and violent conflict. This in turn has led to securitised and repressive governance that further marginalises minority groups and is abused by corrupt actors in state institutions. With eroding trust in government and limited access to services, many members of minority groups are attracted to the radical rhetoric of non-state armed groups that promise to rid the state of corruption and nepotism once they gain power.

- Negative feedback and absorption of external resources: A peacebuilding project brings material resources for rebuilding health stations to villages affected by violent conflict. Local contractors divert material for their own gain, or to fulfil obligations to patrons or kin, and attempt to manipulate procurement and tendering in order to let members of their clan profit. This leads to poor project implementation, a bad reputation for the project, and growing dissatisfaction among the local population with service delivery. During a visit, angry youths accost the project managers, leading to heightened security measures in project implementation, more remote monitoring, and higher risks of corruption.

- Unintended effects and further escalation: The regional strongman insists on placing a relative in the project team, which in turn influences the selection of local partner organisations, building sites, and beneficiary groups. This favouritism leads to growing perceptions among the population – and accusations by political opponents – that the project is deliberately neglecting some communities. Since the project is part of a larger government initiative, the bias is ascribed to the ruling elites and fuels contention and even violent unrest ahead of regional elections.

- Contradictory external factors: External actors, such as donors, support state-led governance reforms and offer capacity building to government institutions. They also strengthen civil society actors such as non-violent movements that mobilise for peaceful change and call on the government to address exclusion, corruption, and impunity. At the same time, the non-state armed groups also receive support through funding and training from regional powers and apply increasingly violent means to express dissent and erode the state’s monopoly of power. The state’s countermeasures target all groups that challenge current rule, suppressing even non-violent approaches and decrying civil society groups as ‘terrorists’.

- Resistance to reform: Anti-corruption interventions that strengthen inclusive governance and rule of law are met with resistance by elites and ‘reform losers’. Elite actors who formerly supported the state but now fear losing access to resources and power turn against state actors, undermine their power, and use political campaigns, including allegations of corruption, to stop governance reforms. For example, capacity-building programmes for law enforcement agencies may be instrumentalised to target political opponents, creating more grievances and instability. As a result, the reforms stall, and the impasse feeds into public frustration, loss of trust, and cynicism, further reducing state legitimacy.

2.2 Understanding actors’ networks beyond the state/non-state binary

Given its foundations in governance, much of the anti-corruption literature tends to focus on improving state performance. It highlights state institutions and their capacity along with the role of reform-oriented actors in civil society. Such a perspective is of limited usefulness, however, and a systemic approach can help to interpret the dynamics of social change through a wider lens. Two aspects appear particularly relevant: understanding actors in their social context, which is often defined by informal patronage networks, and overcoming the binary distinction between state and non-state actors.

Some authors highlight the conflict-containing effects of patronage systems. While frequently perceived as extractive and driven by greed, patronage networks can also add to political order and stability when they are used to preserve power and maintain functional social ties.19e459a098ad This appears to be particularly true in cases where patronage makes material resources widely accessible, providing service delivery that formal institutions in a dysfunctional state are failing to provide.2781a10205c9

Since patronage networks can have stabilising effects, interventions against them tend to be destabilising and may have overall negative impacts on conflict dynamics.2cbd2dd6212f The question is how to weigh the social functions of patronage against its extractive functions and how to gradually transform stabilising but exclusive behaviour towards more inclusive interaction.6104369c49c7 There is a need for more nuanced analysis and action research, especially since successfully disrupting or eliminating patronage systems appears to be extraordinarily difficult. This research should question normative frameworks and explore creative institutional solutions beyond the Western repertoire of interventions aimed at formal state institutions.

During the difficult transition from a war economy, with conflict-related income sources dwindling, elites must often find new sources of income to maintain patronage networks and deliver benefits to their constituencies. If they do not, they may lose their power base or it may fragment.df6c353abe73 This search for income can increase the risk of corruption in demobilisation and reintegration schemes.563785115501 In Aceh, in western Indonesia, for example, ex-combatants were frustrated with the lack of post-war assistance and used violence against their former commanders to extract their share of patronage gains from the elites.93d6f24a24a6 In such cases, a more granular analysis of stakeholders and their incentive structure may prove useful. Such analysis could reveal, for instance, what payments or access to resources will enable conflict parties to deliver on their ceasefire promises to their constituencies5d7c11a1bf5d and what provisions are more likely to result in ‘kleptocratic’ modes of governance.

As noted, a systemic view of conflict transformation considers a variety of actors beyond the state/non-state binary who may play crucial roles in achieving social change. While governance literature emphasises the importance of civil society, other non-state actors are often ignored.

Research has shown that in some circumstances, local populations consider non-state armed groups less corrupt than government actors. Such groups often act in accordance with their own strict codes of accountability and integrity.f694612c5756 They may be able to table demands to reduce corruption and improve governance – demands that the government will find difficult to reject.0f0c116dda89 However, while many non-state armed groups use criticism of the corrupt state to mobilise support, they are often unable to follow up with more detailed calls for reform. While lack of capacity is a factor, they may also be reluctant to engage with civil society or with agendas perceived to be dominated by external actors.d3460de9488d

There are many reasons for neglecting non-state armed actors in statebuilding and governance, including legal restrictions. From a conflict transformation perspective, however, it is important to consider transformation of all actors, including non-state armed groups. In post-independence South Sudan, for example, no real distinction existed between the armed-group-turned-ruling-party, namely the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), and state institutions. Indeed, the former armed group’s military became the state statutory army.d7328cf562c4 This newly gained monopoly of power and resources allowed for corrupt and nepotistic behaviour, but corrupt actors were assumed to have a less damaging impact while on the government payroll. As Van Veen and Dudouet point out, the establishment of central state institutions dominated the agenda, and only few foreign actors were inclined to raise ‘sensitive political topics’ around the legitimacy, accountability, and inclusivity of the new government. Outsiders thus underestimated the required transformation process of the SPLM in its new role.398bec0a38a5

3. Working in conflict and corruption

When we consider peacebuilding in corrupt environments, it is important to make a distinction between working around, working in, and working on corruption and conflict:

- ‘Working around’ corruption during conflict means that agencies avoid the issue of corruption or treat it as a negative externality, following compliance rules.

- ‘Working in’ corruption and conflict means that agencies recognise the need to be more sensitive to corruption and conflict dynamics and adapt policies and programmes accordingly.

- ‘Working on’ corruption and conflict means that agencies address corruption and violent conflict deliberately and seek to engage with the drivers of both.4c07394e1f7e

From a systemic perspective, it is clear that working around corruption – in other words, externalising corruption from the peace process – is not an option. If left unaddressed, corruption will undermine the efficiency, effectiveness, legitimacy, and credibility of any peacebuilding effort. However, peacebuilders may feel reluctant to move from ‘working around’ towards ‘working in’ and ultimately ‘working on’ corruption. As our interviewees told us, third-party actors who engage conflict parties in a peace process might shy away from calling out actors who are complicit in corruption. They may even be unwilling to use the ‘c-word’, as in many contexts of violent conflict, it is dangerous to address corruption explicitly even though it is everywhere. Rather than avoiding the topic entirely, outsiders need to be careful about language and reframe corruption in a peacebuilding context. This requires an inclusive attitude that stresses the need for accountability, transparency, and integrity instead of talking solely about corruption.

Another challenge lies in the ‘zero-tolerance’ approach to corruption that many funders espouse.01a93d74a86b Their aim is to show that corruption is unacceptable and that organisations that fail to prevent corruption will be held responsible. Such an absolute principle, however, is difficult to implement in contexts of systemic corruption.7d854fa2ff95 It is possible to balance due diligence with a learning culture that acknowledges mistakes and failures.

The remainder of section 3 discusses implications for working in corruption and conflict: how to integrate analysis and strategic assessment (3.1), how to demonstrate corruption and conflict sensitivity (3.2), and how peace support organisations should conduct themselves in contexts of entrenched corruption (3.3). Section 4 will then consider how to work on corruption and conflict and identify entry points for integrating anti-corruption efforts in conflict transformation and peace support.

3.1 Enriching analysis and strategy: Political economy, power, and corruption in peace and conflict assessments

A first step towards integration of anti-corruption perspectives in conflict transformation is to carry out a context analysis. For both anti-corruption and peacebuilding practitioners, a further integration of analytical approaches could prove helpful. While the anti-corruption community is accustomed to applying political economy analysis and power analysis, it could profit from a more comprehensive integration of specific aspects of conflict analysis. Likewise, practitioners concerned with conflict transformation can benefit from a more systematic power and political economic analysis of war and the transition towards peace, potentially in the form of ‘continuous analysis’ through so-called adaptive approaches.a294c079fb34 While these are not new ideas,d19c313a30ef it appears they have not been put into practice. To realise a proactive approach towards working in and on corruption, it is helpful to understand why this is the case.

Explore further use of political economy and power analysis

Peace and conflict analyses should systematically integrate considerations of political economy and seek to understand economic incentives and power structures, just as they currently consider political stakeholders and networks. Such an analysis should go beyond highly aggregated indices of perceived corruption and define specific root causes, drivers, and symptoms through discussions with all stakeholders. Stakeholders’ perceptions often differ strongly, and views of some identity groups may be marginalised if intentional steps are not taken to obtain an inclusive perspective.a1c4066b9220 In particular, the analysis should be attuned to gender sensitivities.9b738a9a85ec

This is not to say that adding such analysis is straightforward or that all current conflict analysis necessarily ignores these phenomena. However, economic concerns often are not considered to be at the core of strategic considerations.78f7bd4a7451 Peacebuilders may also be ill-equipped to analyse and understand economic networks and their actors, and units of analysis may differ between analyses with different focuses.

Still, a systemic analysis of a conflict that takes corruption into account could reveal destabilising aspects of the political economy, norm-violating behaviours that undermine trust in the peace process, and forms of corruption that undermine service provision and make it difficult to rebuild social cohesion.1df1a7d91df5 Power analysis could also identify strategic pressure points at different tracks that offer possibilities to mobilise change agents, deal with resistance, and facilitate transformation.55ba9b76f5d2 Finally, political economy analysis will often highlight the international and regional dimensions of a conflict, potentially suggesting new approaches or opportunities. This means that peacebuilding organisations should be open to pooling or sharing their analyses and extending their focus.

Understand destabilising effects of corruption in the context of peace processes

Integrating political economy analysis with an assessment of peacebuilding needs and entry points for peace support can help practitioners prioritise anti-corruption interventions. Instead of addressing all aspects of corruption simultaneously in the same manner, these aspects could be prioritised according to their significance for peace.f07643812668 When one examines the linkages between conflict and corruption, different leverage points for peacebuilding can be identified with a short-term or a long-term perspective.

From a short-term perspective, one geared to conflict management and stabilisation, priority should be given to those aspects of corruption that have the potential to derail a peace process. The earlier example of patronage networks13f736c50eb9 that ensure former combatants’ livelihood needs illustrates this point. If wartime resources are no longer available to sustain combatants, patrons need access to other resources to maintain and control their constituencies. Demobilisation and reintegration programmes aim to provide income opportunities for fighters but have often failed to acknowledge the political and social relevance of patronage networks. Similar corruption challenges that could derail peace processes include the embezzlement of humanitarian aid and corrupt deals in security sector reform programmes.fd4626dbab8d Peacebuilders have often underestimated the opportunities for corrupt behaviour in such programmes. Whether these types of corruption have destabilising effects, however, depends on the specific context. A combination of conflict transformation and anti-corruption perspectives could lead to innovative approaches in dealing with these challenges.

From a longer-term perspective, one geared to conflict transformation and conflict prevention, priority should be given to aspects of corruption that cause severe grievances that in turn could hinder reconciliation and reignite violent conflict.510460e35a2c As noted earlier, these aspects often concern state legitimacy and trust. It is often not clear to what extent project-level interventions can improve citizens’ trust in the state if elite capture and political corruption continue to cause grievances. Such interventions often take the form of governance projects that aim to build institutions and improve transparency and accountability in public service delivery at local level. While such activities may improve the quality of public administration, their significance may be overestimated if political processes do not also increase legitimacy and trust.

Promote internalisation, local knowledge, and dynamic monitoring

This last aspect concerns how analysis and assessment are undertaken. While methodological guidelines give detailed analytical instructions and information technology-based solutions offer ever-growing opportunities to integrate big data, the question remains: Who uses this information and turns it into actionable knowledge? Outsiders’ ability to parse the diverse motivations, interests, and grievances of local actors is likely to remain limited, and they need to accept that domestic actors are often best placed to judge what is and is not harmful corruption in a particular context. This local knowledge can be employed to predict deals that stakeholders may strike to advance their goals, undermining long-term conflict transformation in the process.

Increasingly, conversations within the conflict transformation community highlight the need for localised approaches that prioritise local expertise while building on less extractive models of assessment and intervention.9891eaf34ac4 These recommendations resonate with similar discussions in the anti-corruption context. If local team members are placed in charge of analysis and monitoring processes, their experiences and tacit knowledge can be effectively leveraged while being complemented by external expertise.bb6907a21dbd This can shine a light on informal structures and connections and help counteract international actors’ tendency to uncritically apply the ‘lessons’ of the last crisis to the next, irrespective of varying contexts.

As a volatile context develops, the conflict and political economy analysis would ideally be monitored and updated on a regular basis. This remains challenging, however, given limited staff resources and the difficulties in documenting findings efficiently in real time. Most difficult of all is translating knowledge into practice. Practitioners who gather information on stakeholders’ corrupt behaviours often say: we know all this, but what are we supposed to do with this information?6123f91da212

3.2 Enriching ‘do no harm’: Integrating corruption sensitivity into peacebuilding activities

‘Do no harm’ is a peacebuilding mantra, though it can be applied to all aspects of international aid or development cooperation. The concept, coined by a researcher who investigated humanitarian and peacebuilding experiences in violent conflict contexts,99de1a32471e builds on multiple examples of interventions that gave rise to unintended consequences, including different forms of corruption.

Conflict sensitivity, under which ‘do no harm’ falls, is defined as the ‘ability to understand the conflict one is operating in, to understand the interaction between own actions and the conflict, and to use this understanding to avoid negative impacts and maximise positive impacts on the conflict’.bf6f883b8d2f This approach, therefore, also applies to governance, rule-of-law, and anti-corruption work. The anti-corruption literature shows that anti-corruption measures can unintentionally aggravate conflict dynamics or reallocate resources and power: for example, anti-corruption messaging can affect voter turnout or confidence in democracy by reducing trust in the political process.16e59b6f1571 Johnston, in his background paper for World Development Report 2011, states that anti-corruption strategies in fragile contexts must first do no harm and then build trust in order to be effective.3669d8226fd0

Integrate corruption sensitivity

A next step requires practitioners to build on conflict sensitivity and integrate ‘corruption sensitivity’. This means fully understanding the conflict, corruption, and political economy context in which one is operating; analysing how one’s own actions interact with this context; and, based on this understanding, taking steps to avoid destructive impacts and maximise positive impacts on corruption and conflict.

Post-conflict reconstruction often involves large aid funds with little accountability. The pressure to distribute aid quickly and effectively, combined with the low absorptive capacity of local institutions, creates strong incentives for corruption and rent seeking.b5dcd095fbee Le Billon points out potential negative effects of aid flows on local economies.736603d19297 These include providing an enabling environment for corruption through highly inflated local prices and salaries, low accountability, and strong pressures for external agencies to partner with local firms despite high fraud and politicisation risks.

Little has been done to address the structural risk factors that accompany the allocation of external funding and aid resources. While some of the literature offers self-critical and reflective insights,a7586867d13c a more systematic approach towards aid-induced corruption risks and corruption-sensitive peacebuilding is still missing. More methodological consideration will be required to integrate the complementary perspectives of conflict sensitivity and corruption sensitivity.

Manage expectations around anti-corruption programming

Public expectations play an important role in both conflict transformation and increasing transparency and accountability. Anti-corruption programmes that fail to meet unrealistic expectations may lead to public disappointment and deepen social and political distrust. Conversely, setting expectations too low might cause the intended audience to disengage and lead to an ‘expectations trap’.feded05d7b9e

Expectation management is therefore an essential element of corruption sensitivity and conflict sensitivity. Such an approach will require modest and realistic programming that engenders tangible and credible results while transparently communicating positions and principles.8ca985bd0d52 Transparent communication is needed to ensure that transformative approaches are not regarded as complicit with corrupt stakeholders. Such communication, however, presents a particular challenge if it is to be done in a constructive, inclusive, and impartial way that avoids siding with conflict parties that use allegations of corruption in their mobilisation campaigns.

3.3 Encouraging principled approaches towards accountability and integrity

While this report mostly discusses how peace support could address corruption as a social phenomenon within the conflict context, this section will look at preventing corruption in peace support activities such as multi-track dialogue and mediation support and building of local capacities for conflict transformation. It will consider how principled approaches to such work can be enriched by paying more attention to transparency, accountability, and integrity in conflict transformation programming. Mere allegations of corrupt behaviour, however baseless, will undermine the legitimacy and credibility of peace efforts. They should be proactively countered by employing communication policies and enhanced compliance measures that demonstrate transparency.4e3038e49e5b

The following considerations go beyond the technical provisions for project management, which depend on individual donor and agency guidelines and will not be discussed here in detail.

Explore good-enough approaches to due diligence

Many donors adopt a hard-line stance on dealing with corruption, commonly known as a zero-tolerance approach. This requires all instances of corruption, no matter how minor, to be fully investigated, prosecuted, and sanctioned.22a45ce2375b This approach lent political momentum to the anti-corruption agenda in the mid-1990s by sending signals of toughness to impress domestic constituencies, such as taxpayers. It is arguably less helpful in addressing corruption effectively.14d13ab5cfe0

One argument maintains that such policies sanction any reporting on corrupt behaviour and any administrative failures in curbing corruption. While organisations fear such incidents and strive to do all they can to prevent corruption, the temptation to hide mistakes may persist, and therefore important opportunities for organisational learning could be missed.108438e45917 In addition, zero-tolerance approaches potentially discourage whistleblowing within organisations.9d52293d0bfb From a transformative perspective it would be interesting to explore more constructive approaches that demonstrate ‘good-enough’ administrative diligence while also acknowledging failures and developing a learning culture. One way to deal with this issue constructively could be through a ‘phased approach’, which allows donors to be more flexible in how they respond to corruption while giving organisations space to both admit corruption may be a problem and declare an intention to tackle the problem.ddd8088f90c7

Encourage conversations about integrity in conflict transformation

All forms of corruption have the potential to undermine the legitimacy of all stakeholders (see Box 1), including peace support actors themselves. Many administrative guidelines, however, are concerned mainly with petty corruption. They therefore fail to address ‘bigger questions’ around engaging conflict stakeholders and local peacebuilding partners in a transformative way that could contribute to questioning norms and organisational policies.24f66d223dcc Conflict transformation should help create safe spaces for dialogue that addresses social norms and values of integrity and transparency in peace support organisations and among their partners. As noted in interviews, discussing codes of conduct may also provide an entry point for deeper conversations on corruption and the political economy of peacebuilding.

Identifying entry points for community engagement and local partnership is never easy. While humanitarian or development actors often provide obvious material benefits and temporary solutions to practical problems, other peacebuilding interventions need to prove their value differently to win the support of stakeholders. Ending violence and achieving peace certainly offers the most important benefits, which should be in the self-interest of all actors. But often, interviewees said, local actors imply that a little ‘sugar-coating’ may be required to ensure their enthusiastic cooperation.

Box 1. Selected examples of corruption risks in peace support

Following are several types of alleged or real corrupt behaviour that have informed local perceptions as well as the characterisations of peace support actors in the local and international media. Notably, these do not concern commonly identified corruption and compliance risks in peacebuilding projects, such as fraud or bribery, but speak to more systemic effects that occur on all peacebuilding tracks.

Buying support for stability and peace. The flow of the infamous ‘bags of cash’ through Afghanistan is an example of informal practices aimed at buying the support of local elites for statebuilding activities or anti-terrorism campaigns (Lerman and Walcott 2013; Chayes 2015). Financial incentives are also sometimes offered in official peace negotiations to induce conflict parties to cooperate at the negotiating table. In Burundi, for example, payments to ensure participation in the Arusha talks were made to delegates, increasing their wealth but diminishing their support among the population (Margolies 2009). Third-party peace support organisations are seldom directly involved in these practices, which fuel grand corruption, undermine state legitimacy, and allow the rent-seeking behaviours of the war economy to persist and undermine the evolving peace economy (Le Billon 2003; Berdal and Malone 2000). It should be noted that some peace deals carve up lucrative portfolios and resources, and revenue-sharing agreements in unity governments are often (implicit) deals about who gets access to what revenues in order to create a vested interest in peace.

Providing sitting allowances. This is common practice among organisations when conducting workshops, seminars, or other activities that require participants to commit significant time and to neglect their other activities. Such remuneration is often necessary when involving grassroots stakeholders and others who are not participating on behalf of an organisation that already pays them a salary. In many conflict contexts, however, it has become the norm to pay all participants independently of their income situation, and elsewhere ‘cooperation fees’ have been paid to government officials to allow events to be held. Expectation of payment may blur the motivations of participants and stakeholders, obscure genuine commitment, render participants’ expectations difficult to manage, and pose additional administrative challenges (interviews). Despite efforts by donors to address the dilemmas and harmonise practices, little progress has been made.

Providing benefits for wider social networks. Especially in contexts informed by patronage, clientelist networks, and clan-based or tribal social structures, any interactions with external interlocutors such as peacebuilding organisations are informed by social expectations. Generally, the social network expects to benefit from a member’s interaction with external actors, for example, by receiving a share of any renumeration or presents from trips abroad. In this context, social norms do not consider such behaviour to be corrupt; rather, it is perceived as evidence of a well-functioning social network and as a collective mechanism for coping with adversarial living conditions (Baez-Camargo 2017; interviews).

Addressing these expectations in the design of conflict transformation interventions and project implementation is a delicate task. While most third-party actors will have encountered such situations in their work, interviewees noted, many find it difficult to speak about their lessons learned and challenges among third-party peers. There are several reasons for these inhibitions, ranging from reputational risks to fear of failure to an unwillingness to disclose any instance of working around the official rules. Nevertheless, sharing of good practices among peace support organisations will be beneficial. Such organisations should explore how to provide space for difficult conversations in a specific local context and inspire collective learning, for example, through anonymous learning cases as entry points.

Enhance downward accountability

‘Downward accountability’ is a way to increase the transparency of peace support by communicating integrity guidelines directly to beneficiaries. This approach emphasises accountability not upward to donors, but downward to those whom the interventions affect, allowing local actors to take ownership of the process.467408e564c7 Local actors, be they anti-corruption activists or government representatives, often have little information about donor objectives and funds committed and consider donor interventions to be a ‘black box’.22d0aff9036a Transparency in the definition of objectives, funding of activities, and allocation of resources would enable a more constructive and equal engagement of all peacebuilding actors. Such approaches could also be applied to render the implementation of peace agreements, including their funding mechanisms, more transparent, and to avoid accusations of bias regarding the allocation of peace dividends.

Such communication should be sensitive towards risks of manipulation and instrumentalisation. When addressing local communities, practitioners should translate technical language and expert terminology into a more accessible form. Successful dissemination is only possible when the objectives of community-based activities are clearly defined and their contribution to enhancing state-society relations is made explicit.

In violent conflict contexts, sensitive aspects of peace support that cannot be publicly disclosed may need to be conducted confidentially, for example, to protect ongoing peace negotiations or to support non-state armed groups in the transition processes. Moreover, security and risk management may limit the principle of transparency, as security concerns sometimes warrant a more discreet approach in a specific local context. These challenges expose the different interests and principles driving the discourses on anti-corruption and conflict transformation that should be explored further.

Include protection for local change agents in risk management

Conflict transformation requires a comprehensive approach towards security and risk management. This approach should go beyond compliance measures to address political, reputational, operational, financial, and fiduciary risks related to corruption. Risk management strategies should include measures to support and protect local change agents, whether inside or outside government. Anti-corruption efforts regularly involve champions among public servants who often take considerable risks in pursuing their activism beyond their official mandates.

Likewise, civil society organisations, especially smaller community-based groups and informal movements, need support to defend shrinking spaces for civil society activism. Only then can civil society fulfil its role as an anti-corruption watchdog, an active member of oversight bodies, and a participant in social accountability measures.a545c8249afd In addition to funding, this support involves protective measures, such as facilitating contact with international donors and diplomats to reach global audiences and their safety nets, with consulate and visa services, and with international human rights defender programmes. Future steps could also involve funding peer self-help networks to build resilience, solidarity, and mutual care among members.b4bc65c59d2b Such measures, however, might also expose civil society organisations to new risks, such as accusations of foreign funding or meddling.

Reporting on government corruption is among the most frequent reasons for imprisonment and murder of media and legal representatives. Their protection – as well as support to independent media and the justice sector – is therefore a central element of any anti-corruption strategy.deda3fe21538 Advocacy organisations addressing human rights violations and corruption can often mobilise diplomatic attention by naming and shaming perpetrators and by running public campaigns to free imprisoned or disappeared activists.

From a conflict transformation perspective, however, such a ‘noisy’ approach is complicated by neutrality and multi-partiality. These principles do not allow for public accusations or taking sides with conflict parties; rather, consideration must be given to the legitimate concerns and interests of all stakeholders. There is also a risk of political instrumentalisation, as accusations of bribery may be used to damage the reputation of political opponents or weaken electoral and other democratic processes. Transformative actors therefore strive to avoid getting caught in political games and prefer to work quietly in the background.

4. Towards a virtuous circle: Entry points for integrity and transparency

Following the progression of working around, working in, and working on corruption, this section explores how anti-corruption efforts could be integrated into conflict transformation and peace process support. It discusses questions of timing and sequencing, explores apparent trade-offs and dilemmas, and suggests entry points for improving governance and reducing corruption in peace processes and broader peacebuilding activities along different tracks of engagement.

In this section we adopt the language of three ‘tracks’ of mediation introduced by John Paul Lederach in 1997 (Figure 1). While this model’s distinctions are simple and rough around the edges, and it has been criticised as unnecessarily hierarchical,6d35dfa11d88 it is nonetheless a useful and widely adopted framework.

It should be noted that while the tracks are discussed separately, conflict transformation and peace support generally involve multi-track approaches at different levels and across different sectors.e5c59456979e Anti-corruption approaches likewise advocate whole-of-society approaches and multi-stakeholder coalitions.e6e4bd1522f8

Figure 1. Lederach’s three tracks

Source: John Paul Lederach, 1997

4.1 Anti-corruption efforts at track 1

There are good reasons to think that corruption should be addressed as early as possible in transitions out of conflict. Since violent conflict is generally a sign that a political settlement has broken down, peace negotiations are by definition moments of flux when rules are being redrawn. Decisions about ending the fighting cannot be readily divorced from decisions about the post-war order. Likewise, accountability and transparency cannot easily be tacked onto agreements that have already carved up assets for distribution to conflict parties. Hence, corruption should be identified as a priority issue to be addressed during transition processes. If it is not, transitions risk cementing the gains of wartime winners and freezing political settlements in constellations that are unstable, particularly exclusionary, or exploitative.

Act early and look for entry points to gradual approaches

A long-running assumption holds that sequencing in peace processes is essential. The idea of ‘peace first’, with justice, accountability, and anti-corruption coming later, has a great deal of traction among diplomats engaged in negotiations and with mediation support actors who work at the track 1 or 1.5 level. It reflects a desire not to complicate delicate negotiations between conflict parties, concern over the willingness of armed actors to agree to measures that threaten their hegemony over the post-war period, and a genuine belief in the transformative power of processes like national dialogues, transitional justice, or constitution-making that generally follow peace agreements.

Yet ignoring corruption during peace talks in the hope that it can be tackled later is problematic on several fronts. If questions of corruption and state capture are deferred until the ‘right time’, opportunities for positive change can be squandered. Practitioners generally agree that the short-term focus on stability and on ending open violence in the peace agreements and transition processes in Afghanistan, Lebanon, and South Sudan exacerbated corruption and state capture and undermined opportunities for peace in the medium to long term.

The alternative to a sequenced approach is not to attempt to do everything at once, but to adopt a gradual approach that ensures peace processes contain entry points for future efforts. The process should include measures that are not too taxing initially but that provide opportunities to gradually build political ambition and technical sophistication over time.2d6e10332585

Peacebuilders can create entry points for further anti-corruption efforts during peace talks, for example by developing agreed principles on integrity, accountability mechanisms, or promises of reform.6aea1c73362c They can set agendas that promote the inclusion of anti-corruption efforts in peace talks as early as possible,c772db4c32a5 especially since in most contexts anti-corruption activists and local peacebuilders want to address the topic. Giving them space and making their voices heard is an important step towards an inclusive approach to peace talks (see also ‘Look for allies’ below). Reluctance from the conflict parties to discuss the topic directly may be overcome by addressing the issue in a broader context of discussions about inclusive and accountable governance, social justice, codes of conduct, or social norms and principles such as integrity, accountability, and rule of law.352f1866dcbe

Peacebuilders can also appeal to the enlightened self-interest of conflict parties. In the face of lack of public trust in the peace process or particular concerns about specific armed actors, conflict parties may signal their readiness to work towards transparency and integrity through, for example, the public disclosure of assets and incomes of government officials.119a453575dd Mediators and peace support actors may also wish to familiarise themselves with debates over what levels or types of corruption provide conflict actors with sufficient access to resources for them to agree to a peace deal, while limiting that access in ways that lessen the likelihood of corruption becoming ubiquitous and entrenched in society.3f5f7b347e06 This may allow them to help conflict parties and civil society think through the likely long-term implications of deals under negotiation.

Be honest about trade-offs and assess unintended consequences

Practitioners supporting peace processes and anti-corruption efforts regularly struggle with dilemmas around stakeholder inclusion, dealing with ‘spoilers’, and incentives for participation. Approaches focused on peace and those focused on reducing corruption may be in tension, at least in the short term.

Most critically, anti-corruption practitioners and researchers have been tempted to advocate for zero-tolerance approaches and exclusion from peace processes or power-sharing deals of the most openly corrupt actors or those most deeply invested in illicit economies. Such measures risk derailing talks and generating violent resistance.564e36a7ad80 As a result, peacebuilding and mediation approaches have tended to advocate inclusion of all actors and to be sceptical of preconditions for talks, and authors working at the interface of peace and corruption have tended to agree. There is reason to believe that spoilers must be included and that, more broadly, all conflict parties are negotiating in part over access to state budgets or natural resource revenues.12c08169fefd In such contexts, incorporating rival factions, including those deeply involved in illicit economies and predatory practices, in power-sharing arrangements is often necessary to ensure their commitment and encourage cooperation.762b441bdd41 Yet the risks of such a strategy are apparent: entrenching corrupt elites, creating perverse incentives, and undermining the prospects for peace in the longer term.

Navigating these contradictory pressures is perilous, making it all the more important to acknowledge trade-offs and the ways in which peace and anti-corruption may not, at least in the short term, be readily reconcilable. Such an acknowledgement invites dialogue between anti-corruption and peace support actors that could contribute to navigating such trade-offs and improving the prospects for both peace and accountability.

These discussions do not appear to be occurring. Interviews and the literature review indicate that while ‘corruption is everywhere’, the question of how best to address it jointly is seldom on the agenda of international actors supporting peace processes. Providing a confidential space for such conversations might be a first important step towards integration. More clarity on division of labour and shared or differing strategic objectives might be helpful in order to create synergies despite different roles and mandates. Such discussion must also include actors from the context in question, because apparent trade-offs may play out very differently in different contexts and unintended consequences loom large.

Work across silos to improve process design and expertise

If there is value to addressing corruption concerns early and there are also tensions between anti-corruption measures and pressures to reach a peace agreement, it is imperative that anti-corruption and conflict transformation actors speak to each other, cooperate to build synergies, and avoid undermining each other’s efforts.

Mediators and dialogue facilitators often could benefit from enhanced access to expertise on a broad range of issues, from transparency and integrity in power-sharing agreements to natural resource revenue management, post-war reconstruction, and institution building. Only with sufficient awareness and appropriate technical expertise at hand can particular provisions in peace agreements be suggested to the parties and implications considered with them.

A more systematic collaboration between anti-corruption actors and peace process facilitators could be established to create synergies during process design. Anti-corruption actors could also be invited to more actively accompany peace processes to provide expertise and evaluate the likely implications of measures that are being negotiated. This could include knowledge about timing and effectiveness of specific anti-corruption mechanisms. For example, the introduction of mechanisms for transparent natural resource revenue management like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative might not be effective during early transition phases.5d6033685b75 Likewise, specific expertise is required to understand the power constellations that render national or international mechanisms to address elite impunity – such as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) – effective or not. To suggest further action, it would be important to understand whether and how such expertise is already part of mediation support teams or could be integrated into them. While there may not be technical solutions to the deeply political issue of integrating anti-corruption in peace processes, technical expertise is essential.

On the political front, too, cooperation could be beneficial. External support for anti-corruption campaigns, for instance, might have a role in raising difficult issues that mediators are not in a position to tackle and that may be too risky for local actors to flag.3afcde6713f9 Similarly, transparency provisions around aid in the context of post-war recovery and reconstruction assistance could provide entry points for mediators and facilitators to put the issue of transparency and accountability on the table in peace talks or subsequent dialogues. Indeed, local political elites who wish to signal their commitment to reforms often subscribe to large-scale bureaucratic reform programmes.b7899cb5bd3b If carefully supported, such reforms can increase transparency and accountability, although external support for institutional change has a mixed track record and reforms can likewise escalate conflict and strengthen entrenched power holders.

Look for (local) allies to support an integrated approach

Mediation does not rely only on the good offices of a third party perceived as neutral. It also depends on the willingness of people within and close to the conflict parties to convince their colleagues of the need for change. There is a crucial role for insider mediators and change agents who push, quietly or loudly, to do things differently. Successfully integrating anti-corruption efforts into peace processes at track 1 needs to rely on similar partnerships and alliances.

Contributions of external actors are limited by, and dependent on, the commitment and capacities of internal actors in the system of corruption and violent conflict.aecfd5453531 Strengthening the expertise and capacities of these actors – domestic officials, civil society leaders, business and trade union bodies – should be part of both anti-corruption and peace process support. It is also necessary to engage diverse stakeholder groups that could either resist or promote change. Particularly in conflict contexts, informal networks often predominate. Strengthening such networks among pro-reform actors, whether public servants or civil society, can benefit anti-corruption approaches.6aa638a85d7a

Similarly, although mediators and peace support actors rarely set the agenda for talks, they can push for inclusivity and encourage parties to consider issues of concern to broad segments of the population. Both literatures, on peace processes and on anti-corruption, highlight the importance of inclusion, especially of civil society, and the need for gender-sensitive approaches. Both point to the mobilising power of youth and women as motors of change and as bridge builders between different communities.bfcfeabaf93f Of course, these are not homogenous groups, and young people, women, and non-governmental organisations need not be equally invested in the same issues or even agree on basic principles.

4.2 Anti-corruption efforts at track 2

While the integration of anti-corruption efforts at track 1 requires peacebuilders and anti-corruption actors to grapple with difficult trade-offs, track 2 offers more straightforward possibilities for close cooperation and synergies. Dialogue and politically focused tools of peacebuilding can complement technical and institutionally focused approaches to corruption, offering opportunities to address some of their blind spots and weaknesses.

Understand opportunities and limitations of working at track 2

Working at track 2 level involves engagement with actors who have significant influence due to their formal position, expertise, or social standing. These actors can influence decision making through advice, pressure, or their ability to shape processes and standing operating procedures, but they are rarely in a position to directly make decisions or shape outcomes themselves.

One way to think about track 2 actors is as connectors between the top-level leadership and the grassroots level.0a976318f27a This is particularly true for civil society, a key component of the track 2 space. Civil society is often ascribed a privileged role in creating pressure for change and in flagging issues that need to be addressed in peace processes.e520e1020325 Recent experiences underscore that organised interests, charities, faith-based organisations, self-help groups, and other components of civil society have a key role to play in most contexts, with some important caveats.

As connectors, track 2 actors provide entry points and can monitor the process to see whether changes agreed by political leaders are implemented. They are central to the long-drawn struggle for gradual improvements in governance, accountability, and transparency that both peacebuilding and anti-corruption rely on. International actors often lose interest over time, and power holders often have little incentive to improve institutional performance once they have control over state resources. This makes the sustained role of civil society essential.ed7e6eb2e523

The position of track 2 actors as connectors means, however, that they often depend on track 1 actors and are as embedded in power structures and the political economy as everybody else. They are not monolithic, nor are they independent of other political actors and the conflicts between them. Civil society actors can be change agents and spoilers; their motivations, rationales, and values are diverse; and they often disagree about end goals and the means to pursue them. Especially in polarised conflict contexts, civil society actors may be more usefully understood as competing groups with different relations to state and other conflict actors rather than as a wholly independent third force.17ed2bf8e8d8

As a result, anti-corruption actors will not always be peacebuilding actors, and organisations that share specific anti-corruption objectives or peacebuilding aspirations may disagree about other goals and may be on different sides of the larger conflict. In Afghanistan and Indonesia, for example, Islamist organisations and civil society groups hostile to the Islamist political project were pushing for anti-corruption measures in parallel while disagreeing about basic parameters of the state, peacebuilding goals, and gender equality.f35fdecf25a6 Moreover, attempts to work on both anti-corruption and peacebuilding stretch the capacities of local partners, exposing them to additional threats, undermining relationships, and diluting potential impact.febc0109fea9 At least some such local actors, however, feel that their aims of social justice and transformation equally embrace both agendas and do not differentiate sharply between the sectors.007d3a560f26 How broadly or narrowly to build coalitions and the extent to which partnership or shared objectives in the peacebuilding space can support cooperation in anti-corruption measures – and vice versa – is a topic for further exploration.

Facilitate inclusive spaces for dialogue that support transparency and accountability

A keystone of work at track 2 level is providing and facilitating safe spaces for constructive dialogue. Such dialogues are necessary to construct future visions of peaceful development and formulate reform proposals on contentious issues that could be fed into the formal negotiation process at track 1.18dd85a21dfe Particularly in contexts of new political settlements, such spaces can inform post-agreement processes and the development of a peace economy based on integrity and accountability.e41878e8c497 Approaches towards socially strengthening counter-norms that would adhere to these principles of integrity and accountability could take the form of transformative dialogue, a pedagogic technique whereby participants are assisted in imagining new social realities aiding by participatory processes, dialogue, and problem solving.770b231335c2 Such approaches appear more likely to succeed ‘if all stakeholders in society (government, civil society, media, the private sector, business, and so on) are included’.e445c0810016 An integration of anti-corruption efforts in peace processes should therefore follow such an inclusive approach to generate early buy-in and commitment to eventual provisions in a peace agreement.a34a7f2b9119

Combining such dialogues with an anti-corruption emphasis on transparency and accountability can also benefit peacebuilding efforts. By re-establishing connections between communities and with institutions, such spaces have the potential to rebuild trust between groups, to restore faith in institutions for managing and resolving conflict, and to foster social accountability. Facilitated dialogue can bring all stakeholders together for constructive problem solving and can, in combination with governance programmes, strengthen government responsiveness towards citizens’ concerns and their desire for accountable service delivery.f73917360a15

Consider peer exchanges for capacity building

Capacity building is often considered a central pathway to supporting anti-corruption measures. Yet as the above discussion suggests, integrating anti-corruption approaches in peace processes is an inherently political undertaking. There are no purely technical fixes, and training measures or the development of ethical codes for civil servants are ineffective as long as systems do not change and principals continue corrupt behaviour.31111fabb0de

Even where capacity building is an important element in broader change processes, a careful assessment of the sorts of capacities needed in context is essential. Often the difficulty is not to know what best practice – or simply good or better practice – looks like, but to think about how needed changes can be achieved realistically. To this end, peer exchanges across diverse post-war contexts, among actors that underwent similar transformation processes, are often more fruitful than training that focuses on technical skills.c1d61fccf8de Such peer exchanges relate more directly to the situations and choices facing actors and demonstrate how changes, including of social norms and expectations, have been achieved in similar situations. In addition, where capacity building is used, it need not be defined by the state/non-state binary. While the statebuilding and governance literature tends to prioritise state actors, the need for capacity building and the potential for transformation will often be higher among civil society and non-state armed actors who are being brought into state structures as part of a peace process.3c3ef693be2c

Explore the potential of ‘integrated infrastructures’ for peace and accountability

In many contexts, peacebuilders consider ‘infrastructures for peace’ a relevant element of their efforts. If peace is an ongoing process rather than a steady state, maintaining it requires formal and informal institutions that support efforts to rebuild constructive relationships and overcome conflict.b14389b55e30 Such infrastructure promises to be most effective if it can bridge anti-corruption and other reform efforts. Just as bus lines should connect to train stations, institutions supporting dialogue and peace should connect to anti-corruption bodies and campaigns.

One of the key elements of anti-corruption efforts is the establishment of anti-corruption commissions, agencies, and similar independent organisations that have a broad and permanent mandate to investigate corruption inside and outside government with neutrality. Such agencies are established in the context of broader governance reforms and at times as part of an overall institution-building effort that takes place during the implementation of peace agreements and in post-war recovery and reconstruction. Despite mixed results, there is a consensus that, if done ‘right’, such bodies can provide entry points and institutionalise a focus on anti-corruption issues in the medium to long term.9cfb5c7abc02

Increasingly, similar bodies, often with distinct mandates, are part of peace processes. Such institutions may lend themselves to wider partnerships and alliance building with actors rallying for social change, including on anti-corruption. It would be interesting to explore the linkages between anti-corruption commissions and infrastructures for peace to see what these structures can learn from each other, as has been attempted with EULEX in Kosovo and CICIG in Guatemala.a22424f7acbd At a minimum, the networks and organisations that form the infrastructure for peace must conduct themselves with transparency and accountability (see section 3).

Transitions to peace often include provisions for transitional justice. Since those who abuse power for material gain typically show little regard for human rights, links often exist between investigations into corrupt behaviour and probes of other wartime transgressions.053c514ed92c Indeed, prosecution of corrupt behaviour sometimes proves more feasible than prosecution of war crimes and can be a way to ensure a measure of accountability in the absence of more comprehensive transitional justice measures.2c1a47f9e1e8

Peacebuilding, transitional justice, and anti-corruption actors should try to take up each other’s concerns and pursue them through a more integrated approach. There have been some encouraging moves in this direction. Although the accountability and integrity of truth and reconciliation commissions as well as that of reparation packages is questionable in many instances,292001420606 some recent examples, such as the Truth and Dignity Commission in Tunisia, have integrated some elements of anti-corruption. Also,the vetting procedures in Kenya’s Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission are said to have had a strong focus on identifying corrupt officials.b087889b9de8 Meanwhile, specialised ‘corruption truth commissions’ are under discussion as a means to investigate and publicise past abuses by public and private actors.a173faf7ef6c Such commissions could ‘manage a process by which amnesty would be offered to those who had engaged in unlawful corrupt acts, in exchange for a full and truthful accounting of the corrupt conduct that they had perpetrated or witnessed’.1388636a6f8f

Despite these recent innovations, joint learning is required to explore the links, potential trade-offs, and effectiveness of integrating transitional justice, infrastructures for peace, and (transitional) anti-corruption measures. Such an integrated perspective would treat transitional justice as part of a wider process towards inclusive and accountable governance in which issues of redress, restitution, and reconciliation are answered with mechanisms that provide state accountability for past abuses of power, including corruption and state capture.b25418c106f5

4.3 Anti-corruption efforts at track 3

Track 3, the grassroots level where community leadership and organising takes place, is arguably at the bottom of the corruption chain. Communities and local leaders may find themselves exposed to demands for bribery and other petty corruption by government officials or non-state power holders and dependent on patronage for services and security when weak state institutions fail to deliver. Past attempts to build anti-corruption initiatives around local demands in ‘society-led’ approaches have generally been unsuccessful, as they tend to overestimate the ability of subordinate actors to change systems of power and can expose community members to harm.b61556eb1323

Yet while attempts by outsiders to craft anti-corruption activities around community demands have not succeeded, grassroots protests and activism are also often the strongest voice against corruption and in favour of social change. The track 3 level is the one where a ‘critical mass’ for change can be achieved by engaging diverse actors to make transformation feasible and sustainable.a47c1b2c80d0

As such, the track 3 level represents an important entry point for combining anti-corruption and peacebuilding work and holds out significant opportunities for synergies. Both peacebuilding and anti-corruption actors need to take social and downward accountability more seriously and to better understand the role of citizen engagement and protest movements in effecting peaceful change.f4546cd445fb Moreover, only sustained engagement in education at the grassroots level can shift public norms, beliefs, and attitudes.

Support social accountability

Under the heading of social accountability, anti-corruption efforts regularly focus on equipping civil society with tools to hold the state accountable, ideally building on existing grassroots initiatives. Often, such approaches also aim to strengthen data collection and publication so that civil society and business groups can monitor public budgets and procurement processes.df37b752dbc4 Such initiatives have benefited from the access and information sharing offered by, for example, social media. Ideally, social accountability programming not only helps to prevent corrupt behaviour but also empowers civil society, making it popular among donors wishing to promote accountability and good governance from a more people-centric approach.e08278cf2014

Similar approaches have been developed for public monitoring and social auditing in peacebuilding, an example being the peace barometer initiative in Colombia. Building on an inclusive and participatory process of data collection, comparison, and joint regular reflexive dialogue on the results, this mechanism helped to monitor and verify the implementation of 578 stipulations (actionable commitments) in the 2016 peace accord.4363db1bd460 Such approaches are also likely to be important for monitoring, follow-up, and local ownership of specific transparency and accountability provisions in any peace or power-sharing agreement.91f5d9aad730

Beyond monitoring the implementation of a peace agreement, social accountability mechanisms can help restore trust in public authorities and strengthen social cohesion (see Box 2). If done in an inclusive way, these activities bring together different parts of society through, for example, community monitoring of service delivery at the municipal level. Anti-corruption tools like participatory budgeting and citizen report cards accomplish a similar purpose.

As noted earlier, poorly implemented social accountability programming can expose civil society and community members to harm. Moreover, in (post-) conflict contexts, the position of civil society actors in the conflict must be kept in mind (see ‘Understand opportunities and limitations of working at track 2’ above). The approach can invite confrontation and further polarisation, and because budget data can be difficult for citizens to understand, it may lend itself to disinformation campaigns aiming to discredit public authorities.a741bc65f835

Box 2. Social accountability in DDR programmes

Disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programmes play an important role in the context of ‘post-conflict’ interventions. Meant to prevent further violent conflict and contribute to the community reintegration of former combatants, these interventions bring a significant amount of external resources into the conflict context. As noted in section 3, they provide ample opportunity for malfeasance on the part of both international and local actors – the infamous lists of ghost soldiers being just one of many examples (Bryden and Scherrer 2012).

Assessments of such programmes have repeatedly pointed to a structural, systemic level of corruption that cannot be countered with formal compliance mechanisms but needs to be addressed systematically at all stages of context analysis, project design, monitoring, and evaluation within the wider context of security sector reform and governance. Approaches to enhance accountability need to be understood in the local context with particular attention to clientelistic structures (Sedra 2012). In some cases, such as the reintegration structures managed by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in the Philippines, these experiences have led to community-based approaches that consider the existing patronage networks (Dudouet, Lundström, and Rampf 2016). While the strengthening of patronage networks in the process of transformation is often seen negatively, their contribution, in the Moro case, to maintaining a collective identity also helped keep the group together during transitions. In the light of such individual examples, the impact of DDR programmes on the political economy of patronage networks should be studied in order to understand their overall effectiveness.

Nonetheless, the social accountability approach could be a shared tool to align peacebuilding and anti-corruption efforts at the grassroots level. In such attempts, conflict transformation can bring a focus on cohesion, facilitation skills, and process design to the table. This could offer opportunities to overcome some of the difficulties that can accompany the social accountability approach. By engaging all stakeholders in a sustained dialogue on accountability and integrity, exploring different perceptions of these concepts, and recognising different needs, practitioners can mitigate some of the risks. A sustained dialogue would also engage groups that are excluded from conventional social accountability programming by lack of (social) media access. Developing such inclusive process designs through collaboration between anti-corruption and conflict transformation actors could present an opportunity to explore commonalities and add value to each other’s efforts.

Extend alliances to the grassroots level, but be aware of limits to external support

Mass protests against corrupt elites have repeatedly provided pressure for peaceful change, with protests against corruption and impunity in the Arab world and Latin America, as well as in the global North.836a5a48d893 Recent research in conflict transformation has paid increasing attention to social and protest movements and their agency in order to understand how they can contribute to peaceful change.c054b57e4c3e

Popular demands and protests can help put anti-corruption issues on the agenda during transitional processes and in negotiated peace agreements. In engaging with such movements, it is important to keep the limitations of external support in mind. As noted above, it is ultimately coalitions of domestic actors, often across all three tracks, that are able to achieve change. External peacebuilding and anti-corruption actors can supply expertise and support networking, but at the same time they can inadvertently stifle movements, discredit their allies, or get in the way of more dynamic alliance formation.