Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption risks and the anticorruption framework in Brazil, with a focus on subnational government bodies and the urban transportation sector.

Background

Formerly under Portuguese colonial rule until 1822, Brazil’s historical trajectory following independence was marked by a series of coup d'etats, armed revolutions and dictatorships. The country experienced two periods of authoritarian rule – the Getúlio Vargas regime (1937–1945) and the military dictatorship (1964–1985) – before finally beginning its transition to democracy in 1985.

Corruption under the military regime was pervasive, although censorship curtailed the public dissemination of allegations against the armed forces and their allies. The period of rapid economic expansion known as the Brazilian Miracle (1968–1973) was driven by large-scale investments in infrastructure, particularly highways and hydroelectric power plants across the country. During this time, economic groups – most notably construction firms – that supported the regime were systematically favoured (Campos n.d.), thereby creating fertile ground for corrupt practices in the infrastructure and procurement areas.

Since the democratic transition in 1985, corruption has persisted across federal, state, and municipal governments, permeating multiple policy areas. At the federal level, corruption scandals have occurred under various presidential administrations, often threatening to undermine democratic resilience in Brazil.

The first directly elected president after the 1988 democratic constitution, Fernando Collor de Mello, was impeached in 1992 due to involvement in a corruption scandal (Ramalho 2007). During the first term of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula) (2003-2006), members of his Workers Party were accused of illegally paying parliamentarians in the national congress to support the government’s legislative agenda (the vote-buying scandal became known as Mensalão) (Brasil Paralelo 2025). In 2013, during the administration of President Dilma Rousseff, millions of Brazilians protested to demand better access to public services (the protests started as a response to increased costs of urban transportation services) and against corruption (Watts 2013).

At the same time, there have also been significant anti-corruption gains since the adoption of the 1988 constitution (Praça & Taylor 2014). Key developments included the creation of the office of the comptroller-general, the establishment of specialised anti-corruption task forces, and increased public investment and autonomy for the federal police and the public prosecutor’s office. Interinstitutional initiatives – such as the national strategy to combat corruption and money laundering (estratégia nacional de combate à corrupção e à lavagem de dinheiro) – also played a central role. In addition, relevant legislation was enacted, including the Freedom of Information Law (2011), the Clean Companies Act (2013) and the Organised Crime Law (2013).

Following the mostly gradual pace of reforms until the 2010s, there was a “big push” moment with the anti-corruption investigation known as Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato) (Da Ros & Taylor 2022). While the creation and investment on the consolidation of anti-corruption institutions were led by the federal government, Operation Car Wash was led by criminal justice actors, namely the public prosecutor’s office, the federal police and the judiciary.

Beginning in 2014 and lasting until 2021, Operation Car Wash uncovered large-scale money laundering, bribery and kickback schemes implicating private corporations (mainly construction companies), Petrobras (a state-owned oil company), public officials and politicians. Construction companies paid bribes to be favoured for Petrobras’ construction projects; kickbacks were also used to finance the campaigns of various political parties. It marked the biggest anti-corruption investigation in the history of the country, reaching 295 arrests and 278 convictions (Brito & Slattery 2021), implicating a range of figures from the private and public sectors (Watts 2017). Petrobras and the construction company Odebrecht were also implicated of bribing heads of state and officials to obtain contracts in other countries, especially across Latin America, triggering significant political fallout across the region; at least 41 countries have legal cooperation from Brazilian authorities to support domestic investigations relating to Operation Car Wash (Cheatham 2021).

Operation Car Wash has been met with backlash by some political figures who question the neutrality of the investigatione7595544c42f (Barros 2022). Former president Michel Temer (who assumed the position following the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff) was accused of taking bribes for his political party and to endorse a company’s payment of “hush money” to interfere in the operation (Phillips 2017). Former and current president Lula was investigated for corruption allegations under the operation and convicted by Judge Sergio Moro in 2017. However, in 2021 a supreme court judge annulled the conviction on the basis that Moro did not have jurisdiction over the case. This was followed by a 3-2 supreme court ruling that Moro had acted without impartiality. The UN Human Rights Committee also concluded Moro had acted without impartiality (Neuman 2021; UNHR 2022).

In 2018, former president Jair Bolsonaro was elected following a campaign using heavy anti-corruption rhetoric; however, after assuming office, he is considered to have significantly undermined the anti-corruption institutions built over the past decades (Lagunes et al. 2021). Political interference and the loss of independence in anti-corruption bodies and the discontinuance of the taskforces were documented (Transparency International Brazil 2019). Bolsonaro was also alleged to have illegally sold Saudi jewellery, received as a gift to the Brazilian government (Wright 2024), and of being involved in corrupt vaccine deals during the COVID-19 pandemic (Phillips 2021).

The Bolsonaro administration was also associated with democratic backsliding in Brazil, with concerns raised over his attacks on the electoral system, NGOs and opponents, as well as his close ties to the military. The administration radicalised his supporters who attacked federal government buildings on 8 January 2023 after Bolsonaro lost the elections in 2022 (Phillips 2022). In 2025, he became the first president to be sentenced by the supreme court for leading an attempt of coup d’état and the attempted abolition of democracy and the rule of law (Richter 2025). This and other investigations and decisions led by the supreme court justice Alexandre de Moraes concerning Bolsonaro and his allies have proved polarising, with supporters arguing they have helped safeguard democracy while critics allege judicial overreach (Phillips 2025).

Lula won the 2022 elections and, after the start of his third mandate as president in 2023, the Brazilian federal government committed to reinforce its democratic institutions. Nevertheless, some observers have concluded that the government has not yet prioritised measures to counter corruption despite attempts to reverse the setbacks faced in previous years (Transparency International Brazil 2025a). In 2025, Brazil’s current democratic regime reached its 40th anniversary, the longest continuous period of democracy in the nation’s history. Corruption is still regarded by its citizens as one of the main problems facing the country (Coelho 2025).

Extent of corruption

According to Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI),a589175d08ea Brazil scored 34 out of 100, marking its lowest score since 2012 and placing it 107 out of 180 countries (Transparency International 2025). This score falls below both the regional average for the Americas (42) and the global average (43). Compared to 2012, Brazil’s score has declined by 9 points, reflecting a persistent downward trend over the past decade. The country’s highest CPI scores were recorded in 2012 and 2014, when it reached 43 in both years.

The recent decline in Brazil’s score has been associated with several institutional and political developments. These include the supreme court’s decision to suspend fines imposed under leniency agreements with firms involved in corruption scandals, political appointments in Petrobras and congress’s increased control over the national budget, particularly following the expansion of legislative powers concerning budgetary amendments (TI Brazil 2025a).

Figure 1: Transparency International’s CPI scores for Brazil (2012-2024)

Source: Transparency International 2025.

The Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2024 reports a deterioration in Brazil’s democratic governance, especially during the final two years of former president Jair Bolsonaro’s term. It highlighted the systematic dismantling of existing anti-corruption frameworks and institutions, including the dissolution of task forces, the imposition of secrecy over official documents and governmental activities, and political interference in key oversight institutions, including the office of the attorney general and the federal police. In the anti-corruption policy indicator, Brazil received a score of 5 out of 10 in 2024, continuing a downward trend (BTI 2024).

Figure 2: BTI’s anti-corruption policy indicator scores for Brazil (2006-2024)

Source: Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2024.

Source: Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2024.

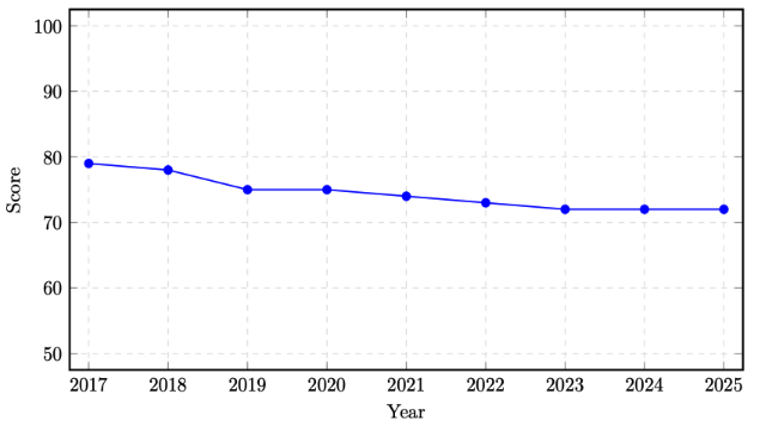

Freedom House classifies Brazil as a “free” country, assigning it a Global Freedom Score of 72 out of 100. Although Brazil’s score has experienced a modest decline since 2017, it has remained stable since 2023. Nonetheless, corruption in Brazil is recognised by the organisation as systemic among elected officials and continues to contribute to public disillusionment with political institutions. Freedom House also highlights high-profile corruption scandals involving members of the Bolsonaro family, including a money laundering scheme associated with one of the former president’s sons’ companies, as well as Jair Bolsonaro’s attempt to illegally sell the gift of jewels from Saudi Arabia (Freedom House 2025).

Figure 3: Freedom House’s Freedom in the World scores for Brazil (2017-2025)

Source: Freedom House 2025.

According to the World Bank’s 2023 Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), Brazil scores -0.5 on the control of corruption indicator1445360980ef (on a scale ranging from -2.5 to 2.5) bringing it almost into the bottom-third of countries measured globally (World Bank 2024). In comparison with previous assessments, Brazil registered a score of -0.1 in 2015 and -0.48 in 2018, suggesting a significant deterioration in anti-corruption efforts, particularly from 2018 onwards. Other WGI indicators also reflect a worsening governance landscape relative to 2013, including declines in the scores for rule of law, regulatory quality, government effectiveness and political stability.

Table 1: Brazil’s scores on the World Bank’s Governance Indicators (WGI) in 2013, 2018 and 2023

|

Year |

2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

|||

|

|

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

|

Voice and Accountability |

0.42 |

60.56 |

0.38 |

59.71 |

0.38 |

59.8 |

|

Political stability |

-0.26 |

36.97 |

-0.46 |

29.25 |

-0.41 |

28.44 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.12 |

51.18 |

-0.52 |

33.33 |

-0.55 |

32.08 |

|

Regulatory quality |

0.15 |

56.4 |

-0.29 |

40.48 |

-0.3 |

40.09 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.09 |

52.58 |

-0.3 |

42.86 |

-0.31 |

41.98 |

Source: World Bank 2024.

According to Transparency International’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) 2020, Brazil is classified as having a “moderate” risk of corruption within the defence sector. The report underscores that the Bolsonaro administration was marked by an expanded political role of the armed forces, evidenced by the appointment of numerous former military officials to high-ranking government positions. It further notes that military operations are particularly susceptible to corruption due to persistent deficiencies in transparency, oversight and procurement practices (GDI 2020).

Finally, data from Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer (2019) reveals that 90% of Brazilians perceive corruption in government as a major problem. Additionally, 11% of respondents reported having paid bribes in the past 12 months to access basic public services (Transparency International 2019).

Forms of corruption

Political corruption

Political finance violations

Corporate financing of political candidates was permitted in Brazil from 1995 to 2015. During this period, campaign donations were highly concentrated, with a small number of corporations and individuals providing the majority of financial contributions (Mancuso 2015; Mancuso & Speck 2015). In the 2014 presidential election, for example, 94% of campaign funding originated from corporate donors (Mancuso et al. 2016). When considering both presidential and legislative elections in 2014, just 33 wealthy individuals and approximately 400 companies were responsible for three-quarters of all campaign contributions (Carazza 2018).

A substantial portion of these donations was irregular, illicit or not officially reported to electoral authorities, practices widely known as caixa dois (second register). During the period in which corporate campaign financing was allowed, the election of a congressional representative funded by a company was associated with an increased likelihood that the company would secure public contracts in the subsequent legislative term (Boas, Hidalgo & Richardson 2014).

In an effort to curb corruption, the supreme court prohibited corporate donations to political candidates and parties in 2015. Since then, only individuals have been permitted to contribute to electoral campaigns, with donations capped at 10% of the donor’s previous year’s income, (however, candidates can still self-finance their own campaigns). Campaign financing has since relied predominantly on public funds, allocated proportionally according to each party’s representation in the national congress (TSE 2016).

One consequence of this prohibition was an increase in individual contributions from corporate executives and directors to political candidates (Bragon 2020). For instance, Balán et al. (2023) describe how members of family-controlled firms circumvented the ban on corporate contributions by replacing them with individual donations which they politically benefited from.

However, it is possible to track individual donations through the electoral supreme court’s (TSE) annual financial reporting system. As good practice, the TSE hosts the data in machine-readable formats (Transparency International 2025b) and ranks the biggest individual donors as well as the amounts of the candidates’ own donations to their campaigns.

Despite progress in regulating political finance, integrity gaps reportedly persist. Gehrke (2025) argues that the Brazilian system still lacks stricter oversight of candidates’ asset declarations, robust mechanisms for preventing conflicts of interest and stronger enforcement against illicit campaign financing (Gehrke 2025). Furthermore, the current electoral system still faces fraud reports with the existence of phantom candidates (candidatos laranja) to receive public funding (Mattoso et al. 2019) and to manoeuvre gender quotas (Do Lago 2025). Current legislation has also been unable to curb the illegal funding of disinformation that harms Brazilian elections. In the 2018 presidential election, corporations illegally financed disinformation campaigns on WhatsApp (Campos Mello 2018). Since 2017, candidates have been obliged to report their spendings on online campaigns, but Grassi (2024) concludes more transparency and control is still needed to confidently identify whether firms are illegally financing online political advertising and disinformation. Finally, there are also reports that organised criminal groups channel funds from their vast illicit economies into political campaigns, especially at the subnational level (Freitas 2025). Cavalari (2024) describes how evidence from the 2024 municipal elections points to funds originating from organised criminal groups being used for vote buying and to fund parties and candidates who did not declare it to the electoral authorities, and also that organised criminal groups deployed violence to threaten many candidates.

Congressional budget amendments

Each year, the executive branch drafts the federal budget proposal, which is subsequently submitted to congress for review, amendment and approval. Members of the chamber of deputies and the senate are empowered to introduce amendments and allocate discretionary public spending, within certain legal limits, to benefit their constituencies.

In 1993, a few years after Brazil’s return to democracy, the “budget dwarves” scandal (anões do orçamento) revealed significant abuses of this prerogative. Key members of the national congress, including members of the budget committee and the budget rapporteur, used their authority not to serve their constituencies but to channel resources to construction companies in exchange for kickbacks. These illicit funds were laundered through various means, including the purchase and cashing of winning lottery tickets (Da Ros & Taylor 2022). The scandal led to the expulsion or resignation of dozens of parliamentarians and prompted reforms in the budgetary process. These reforms sought to limit the powers of the budget rapporteur and to promote more collective decision-making mechanisms rather than individual control over budget amendments(Da Ros & Taylor 2022).

However, after a few decades, between 2020 and 2022, a similar scheme emerged. The role of the budget rapporteur expanded beyond merely approving or amending the annual budget proposal submitted by the executive to include the discretionary allocation of new expenditures. This mechanism, widely referred to as the “secret budget” (orçamento secreto), enabled the budget rapporteur to secure legislative support to the government by secretly creating new expenditures and directing funds to deputies and senators who were aligned with the government, while bypassing transparency and accountability mechanisms (Pires 2022).

Besides this scheme, federal deputies and senators have the right to amend the budget and to allocate parts of the federal budget to their constituencies. Concerns have been raised about the rationality and effectiveness of this spending and its impacts on the provision of public policies (Hartung et al. 2021) since parliamentarians often prioritise their electoral basis. Although the supreme court ruled the “secret budget” unconstitutional in 2022, concerns persist regarding the growing authority of parliamentarians over the allocation of public resources without adequate transparency or traceability. In the context of parliamentarians allocating their individual budget amendments, several scandals have already been documented, including: overpricing in the procurement of agricultural machinery such as tractors (Pires 2021); the use of public funds to pave roads on private family-owned farmland (Weterman et al. 2023); and schemes involving the extortion of bribes from mayors in exchange for directing budget amendments to their municipalities (Pontes 2025).

Bid rigging

In Brazil, all levels of government allocate substantial resources to the provision of public goods and services through public procurement. Bidding processes constitute the principal mechanism through which governments acquire these goods and services.

Bidding processes are vulnerable to various forms of fraud, including collusion among bidders, which may occur through the exclusive or predominant participation of the same group of business partners. Corruption, political favouritism, conflict of interests and the abuse of power have also been evident in tenders in Brazil, manifesting at different stages of the procurement process (ENCCLA 2019). Each stage of the procurement process – such as the pre-tender, tender and post-award – presents specific risks to corruption.

Public infrastructure projects present especially high risks for corruption and bid rigging. Violations of good governance rules, a lack of transparency and social participation are some of the main concerns raised around large infrastructure projects in the country. These can result in a lack of full quality delivery of procured construction services for the benefit of the Brazilian people (Pereira 2018).

Operation Car Wash exposed an extensive network of corrupt practices associated with public procurement and large-scale infrastructure projects. The investigation revealed that construction companies colluded and paid bribes to political parties and public officials in order to manipulate contracts and rig bidding processes. Evidence indicates cartel formation among major construction companies has been a recurrent strategy to manipulate public procurement processes in large infrastructure projects in Brazil (Global Competition Review 2017). Notable other examples include the 2008 case of the Jirau and the 2010 case of Belo Monte, where construction firms colluded to form a cartel for the construction of hydroelectric dams in the Amazon, restricting free competition and manipulating the bidding stage to secure favourable contract outcomes, triggering negative socio-environmental impacts (TI Brazil & WWF Brazil 2021). In 2025, as part of a state of emergency announced following floods in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, emergency procurement processes for rebuilding damaged highways were reportedly manipulated. Evidence suggests the formation of a cartel that colluded to coordinate their bids and secure contracts for the reconstruction of the affected roadways (CADE 2025).

Bid rigging has also been pervasive in the urban transportation sector. A cartel involving nine companies participated in anti-competitive practices in more than 20 public tenders across seven Brazilian states between 1998 and 2013. These practices particularly affected the construction and expansion of metro lines in several major Brazilian cities (OECD 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed vulnerabilities and corruption within Brazil's procurement system. Allegations emerged regarding irregularities in vaccine procurement, including the early purchase of vaccines at inflated prices and without sufficient clinical evidence (Taylor 2021). The use of “emergency contracts” during the health crisis granted governments flexibility by relaxing standard procurement rules to expedite the acquisition of medical goods and services. However, this flexibility also facilitated corrupt practices, including fraud in the procurement of hospital beds (Melo 2020) and ventilators (Slattery & Brito 2020).

Abuse of power

Three decades after its return to democracy, Brazil witnessed an attempted coup d’état against its democratic institutions. Former president Jair Bolsonaro, together with allies within the armed forces, allegedly sought to overturn the results of the 2022 presidential election (Philips 2022). In 2023, the Superior Electoral Court found Bolsonaro guilty of abuse of power and barred him from running for public office for 8 years (Kahn 2023) and in 2025, he was sentenced to 27 years in prison for offences relating to the coup attempt (Wells and Buschschlüter 2025).

Abuse of power also manifested through politically motivated appointments and the instrumentalisation of state institutions. For instance, during the second round of the 2022 presidential election, specifically on the day of voting, the federal highway police (polícia rodoviária federal, PRF) was mobilised to conduct illegal roadblocks in regions known to support Lula, with the apparent intent of obstructing voter turnout (Ionova et al. 2022).

Moreover, abuses of power have been evident within the judiciary. Mendes and Oliveira (2024) argue that judicial corruption in Brazil occurs for both institutional and individual purposes. Institutional judicial corruption refers to practices aimed at securing corporate or collective advantages, such as bypassing constitutional limits on judges’ salaries. Currently a significant number of judges and prosecutors receive salaries above the constitutional ceiling, often lacking transparency (DadosJus 2025). Individual judicial corruption, in contrast, involves the pursuit of private gain through violations of impartiality, conflicts of interest or the misuse of judicial authority (Mendes & Oliveira 2024). Recent investigations have uncovered evidence of multiple judges accepting payments to decide disputes in favour of bribegivers (Madureira 2023; Petrov 2024).

There are also widespread reports of abuse of authority in the environmental sector, causing significant negative externalities. Cases have been uncovered indicating public authorities abuse their power to facilitate wildlife trafficking (TI Brazil 2024), providing fraudulent licences for mining (Amazon Watch 2025) and land grabbing, especially in the Amazon region (TI Brazil 2021). In 2021, the environment minister resigned after the supreme court investigated him on suspicion of obstructing police investigations into illegal logging(Pineda 2021).

Focus areas

Subnational level

Brazil is a federal presidential constitutional republic composed of 26 states and one federal district. These states and the federal district encompass a total of 5,570 municipalities (IBGE 2025). Brazil is often regarded as one of the most decentralised federal systems in the world (Souza 1997) as municipalities are endowed with significant responsibilities for the delivery of public services, including education, primary healthcare, local infrastructure and urban transportation.

Municipal governments are headed by elected mayors and overseen by municipal councils, which serve as their legislative bodies. Despite their administrative autonomy and extensive service delivery responsibilities, municipalities remain heavily dependent on intergovernmental transfers from state and federal governments. Local tax revenues account for only around 20% of municipal budgets (Avarte et al. 2015), which underscores their structural fiscal dependence within the federal system.

Corruption at the local level has significant consequences for the delivery of public services. In Brazilian municipalities, corruption has been linked to reduced economic development (Machoski & Araujo 2020) and poorer educational outcomes (Ferraz et al. 2012). Furthermore, evidence suggests that federal transfers to municipalities in Brazil are associated with an increased likelihood of mayors being implicated in incidents of political corruption (Brollo et al. 2013).

Among the main factors that increase vulnerability to corruption at the local level in Brazil are the absence or weak performance of oversight institutions, as well as limited media attention. The News Atlas (Atlas da Notícia) shows that in 2025, 2,504 municipalities (45% of the total) were considered news deserts, meaning no local media outlet was active there. The Atlas conversely presents a high concentration of media activity in bigger cities such as the state capitals.

The existence and degree of institutionalisation of accountability and anti-corruption bodies vary significantly across local governments in Brazil. To evaluate internal control institutions at the subnational level, specifically the comptroller-general’s offices of states and municipalities, the national council of internal control (Conaci), in partnership with the World Bank, developed a maturity index. This index assessed practices and performance across several dimensions, including control activities (transparency mechanisms and ombuds services), risk assessment, staffing and other institutional capacities. A comparison between the 2020 and 2024 assessments shows that internal control bodies improved their performance by 13% at the state level and by 8% in state capitals. The findings also indicate that most states and their respective capitals have already adopted key regulatory frameworks, such as conflict of interest and major anti-corruption legislation, including the Clean Company Act. On the other hand, the assessment identified a decrease in the number of investigations of fraud and corruption which suggests challenges in consolidating anti-corruption efforts at the local level (Matheus 2025).

The situation is considerably more concerning when examining not only states and their capitals but Brazil’s more than 5,570 municipalities. Although the Federal Access to Information Law was enacted in 2011, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 2,340 municipalities (approximately 40%) have still not approved their own local access to information legislations, and only 27% have established open data portals (IBGE 2025).

The national programme for the prevention of corruption (PNPC), led by the federal court of accounts (TCU), evaluated the susceptibility to fraud and corruption across public agencies and departments from all three branches of government (executive, legislative and judiciary) and at all three levels (municipal, state and federal). The assessment examined whether public entities had mechanisms and practices for prevention, detection, investigation, correction and oversight of corruption. The findings indicate significantly higher risks at the local level: 88% of municipal bodies were classified as having “high susceptibility” to fraud and corruption, compared with 38% at the state level and 20% at the federal level (TCU 2021).

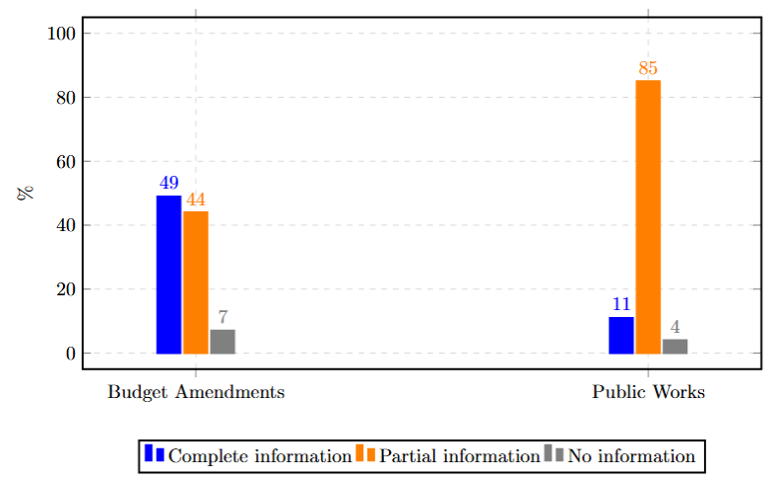

The Transparency and Public Governance Index (ITGP) (TI Brazil 2025c) reveals that, even in states and municipalities with relatively high levels of transparency, there remain critical areas that are opaque and highly susceptible to corruption: public works and congressional budget amendments.

The 2025 assessment indicates that, overall, Brazilian states meet basic standards of fiscal transparency and have adopted fundamental transparency instruments. However, only 13 states (49%) publish sufficient information on federal budget amendments received from deputies and senators, and only three states (11%) provide detailed data on the planning and execution of public works.

Figure 4: ITGP’s indicators on budget amendments transfers and public works transparency (states)

Source: Transparency International Brazil 2025c.

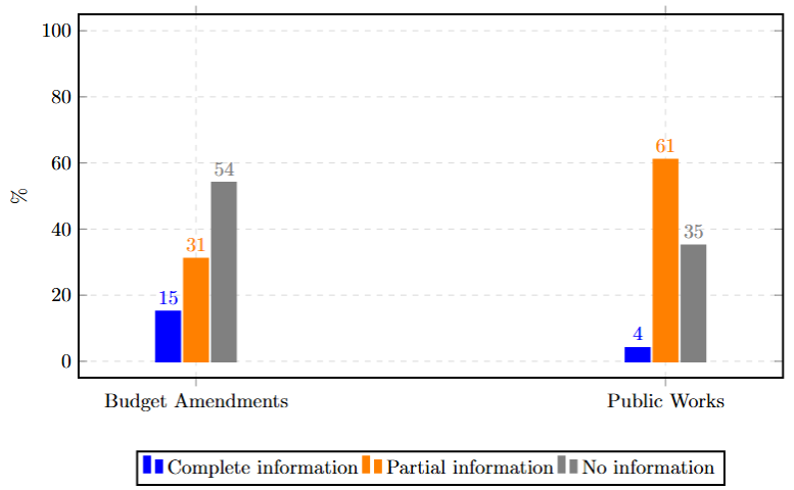

The 2024 assessment of state capitals paints an even more concerning picture. Most capitals have not yet reached even the basic level of maturity in transparency and governance mechanisms. Only 8 out of 26 capitals (approximately 30%) achieved “good” or “very good” transparency scores. Additionally, almost all capitals failed to disclose data on budget amendments, with only 4 out of 26 (15%) publishing this complete information.

Figure 5: ITGP’s indicators on budget amendments transfers and public works transparency (state capitals)

Source: Transparency International Brazil 2025c.

On the one hand, receiving transfers from state and federal governments, whether through parliamentary budget amendments or government transfers, is essential for municipalities to provide local infrastructure and public services. On the other hand, the absence or weakness of oversight and anti-corruption mechanisms raises serious concerns about the integrity of these transfers.

The third iteration of the growth acceleration programme (programa de aceleração do crescimento, PAC), launched by the federal government in 2023, aims to stimulate infrastructure development in sectors such as transportation, sanitation, education and health, investing R$1.7 trillion reais (approximately US$310 billion) (Gov.br 2023). Through the programme, states and municipalities receive federal transfers for the execution of infrastructure projects based on formal terms of commitment.

Previous iterations of the PAC were subject to corruption scandals, and concerns have been raised over the transparency of the third iteration. An audit from TCU uncovered irregularities in multiple public works from the previous PAC iterations, such as overpricing at the Abreu and Lima refinery and the São Francisco River transposition (O Globo 2023). According to the TCU, the most common irregularities were bid rigging and overpricing (Salomon 2007). Besides this, it was found that the institutional design of previous editions did not allow for adequate monitoring of crucial stages, such as the selection of projects, besides the execution and financial progress of public works (Prado 2015).

According to an assessment by TI Brazil and CoST (2024), the transparency standards of the new PAC – measured on the federal government’s transparency portals – were classified as unsatisfactory. The study also highlights that public investments carried out through public concession contracts or public-private partnerships, which represent approximately 57% of total investments under the programme, are not included in the existing transparency platforms. It should be noted that municipalities and states that receive the transfers were not assessed as part of the study.

Urban transportation sector

Responsibility for urban transportation services in Brazil is distributed among municipalities, states and the federal government, as established by the 1988 constitution (Federal Constitution 1988, article 30). The key actors involved in managing and regulating the urban transportation sector include:

Municipal governments hold primary responsibility for urban public transportation services (Federal Constitution 1988, article 30), such as buses, taxis and vans, either through direct provision or via concession contracts.

State governments are responsible for legislating, collecting taxes and managing inter-municipal transportation (Federal Constitution 1988, articles 23 and 155). They also oversee services involving metro and train transport.

The federal government defines overarching guidelines for urban development, including housing, basic sanitation and urban transportation (Federal Constitution 1988, articles 21 and 22). The national urban mobility policy (Law 12.587/2012) establishes the principles, objectives, regulatory framework, management requirements, institutional responsibilities and support mechanisms for municipalities across the country.

Private companies operate transportation services, such as buses, vans, taxis, metros and trains, mostly under concession agreements. These concessions are formalised through public contracts between the government and the company, awarded via public bidding processes for a defined period (Law 8.987/1995).

Construction firms are responsible for executing public works to implement the infrastructure necessary for the functioning of public transportation systems.

Federations are organisations that represent unions and private companies operating within the urban transportation sector.

Oversight institutions (such as the comptroller-general offices of the municipalities and the courts of accounts) are responsible for monitoring the concession contracts, the public bidding processes and to promote efficiency and transparency over the transportation service.

Corruption manifests in the urban transportation sector in the form of fraud in concession contracts, bid rigging, overpricing and in delivering public infrastructure works, as illustrated through several cases.

The federation of transport companies of Rio de Janeiro (Fetranspor) bribed state officials to secure advantages for companies that operated buses, including tax subsidies and authorisation to raise ticket prices. This corruption scheme persisted from 1990 to 2016, with the total amount of bribes estimated at 500 million reais (around US$94 million) (Otavio et al. 2017).

With regards to public works, the construction of a metro line in Rio de Janeiro was reported to have been overpriced by approximately 600% compared to the original contract value (Villela 2017). A similar corruption scheme was uncovered in the São Paulo metro system where, between 2004 and 2014, public officials were bribed by construction firms to manipulate bidding processes in their favour (Tavares 2019).

Additionally, a cartel composed of 11 construction companies was found to have colluded to rig bids for metro construction projects in various Brazilian cities. These companies coordinated their proposals to manipulate tender prices and restrict competition (Lis 2019).

In Brazil, powerful organised criminal groups and militias hold control over bus services in certain regions (Szpacenkopf 2025). In São Paulo, two bus companies with concession contracts for operating in public transportation from 2015 were suspected of laundering money derived from drug trafficking and other illicit activities linked to the criminal organisation First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital, PCC) (Murad 2025; Szpacenkopf 2025). Busch (2024) describes how such are attracted by the primarily cash-based local public transport services as a means to launder proceeds of crime and that their operations may be overlooked by local political figures under the influence of organised crime.

Legal and institutional framework

International conventions and initiatives

Brazil signed the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in 2003 and ratified it in 2005. In 2022, the civil society report on the implementation of Chapter II (Prevention) and Chapter V (Asset Recovery) of the convention concluded that Brazil has made progress in fulfilling its UNCAC obligations. However, it also emphasised the need to further strengthen anti-corruption institutions, policies and practices. Key recommendations included: strengthening institutional guarantees for anti-corruption bodies; adopting and improving oversight and integrity mechanisms in the public service; developing a national programme dedicated to receiving corruption reports and protecting whistleblowers; and introducing stricter accountability mechanisms for judges and prosecutors (TI Brazil 2022).

Brazil ratified the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in 2000. According to the 2022 Exporting Corruption Index, which evaluates enforcement of the convention, Brazil has been downgraded to the category of “limited enforcement”, a decline from its previous classification of “moderate enforcement” (Transparency International 2022). In 2023, the OECD Working Group on Bribery published its phase 4 report on Brazil’s enforcement of the convention. The working group recognised that Brazil had sanctioned certain large-scale foreign bribery schemes but expressed concern about the country’s prospects of sustaining the level of foreign bribery enforcement, noting that authorities had only investigated 28 of the 60 allegations of foreign bribery identified at the time of the report (OECD 2023).

Additionally, Brazil signed the Inter-American Convention against Corruption in 1996 and ratified it in 2002. In 2025, the Organization of American States (OAS) evaluated Brazil’s implementation of the convention. The report expressed concern over the annulment of evidence from leniency agreements and the suspension of fines totalling 8.5 billion reais (around US$1.6 billion) to companies (OAS 2025; TI Brazil 2025a).

Brazil is also a founding member of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and is currently implementing its 6th Open Government action plan. Under this plan, the government and civil society have recognised the challenges of promoting integrity in the infrastructure sector and committed to enhancing transparency and public participation in infrastructure policies, especially the PAC programme.

Brazil is a member of the Financial Action Task Force of Latin America (GAFILAT). The most recent mutual evaluation report of Brazil was carried out in 2023 which evaluated its anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing system against the 40 FATF recommendations, finding Brazil compliant for 10, largely compliant for 29 and partially compliant for 11 (FATF 2023).

Domestic legal framework

Various core corruption offences such as embezzlement and active and passive bribery are criminalised by the Brazilian criminal code (deriving from 1940 and amended multiple times thereafter) with penalties ranging from two to twelve years.

Transparency is supported by three key pieces of legislation. The Fiscal Responsibility Law (Law 10/2000) established core principles for public sector budgeting, expenditure and transparency. The Transparency Law (Law 131/2009) expanded requirements related to budgetary and fiscal openness. Together, these two laws provide the foundation for active transparency, requiring governments to proactively disclose public information. The Freedom of Information Law (Law 12.527/2011) guarantees citizens the right to access public information. It outlines the procedures for requesting and obtaining information. This law is well implemented across federal government agencies and has set a national benchmark for transparency practices (Cunha Filho 2019). Additionally, the open data policy (Decree 8.777/2016) requires that public information be made available in open data formats.

The Conflict of Interest Law (Law 12.813/2013) establishes the legal framework for managing conflicts of interest within the federal public administration.07b633f792e2 It defines what constitutes a conflict of interest, sets out prohibitions and incompatibilities for public officials and designates the ethics committee and the office of the comptroller-general (CGU) as the responsible oversight bodies. The law adopts a preventive approach, establishing rules both during public service and after leaving office. These include restrictions such as prohibiting former officials from providing services to companies with which they had direct contact while in office.

In the private sector, the Clean Company Act (Law 12.846/2013) establishes civil and administrative liability for companies involved in corrupt practices. It also sets the legal framework for leniency agreements, allowing companies to receive reduced penalties in exchange for cooperating with authorities in corruption investigations. In relation to public procurement, the law explicitly prohibits companies from engaging in anti-competitive practices. Penalties for firms found guilty of corruption may reach up to 20% of their annual gross revenue.

The Clean Company Act significantly transformed the anti-corruption landscape in Brazil’s corporate sector by encouraging the creation of integrity and compliance departments and the implementation of internal control mechanisms. A survey conducted with 100 of the 250 largest companies in Brazil found that approximately 90% of compliance professionals credited the legislation with promoting the spread of integrity systems and a culture of compliance in firms. However, they also assessed their organisations’ compliance programmes as still being in an early or immature stages of development (TI Brazil 2023).

The Organized Crime Law (Law 12.850/2013) defines organised crime and establishes criminal procedures and penalties for criminal organisations. The law also introduced the legal framework for rewarded cooperation (plea bargaining), allowing reduced sentences in exchange for providing information to law enforcement and investigative authorities. This instrument has been widely used, particularly since Operation Car Wash, and has led to significant developments in Brazil’s criminal justice system, especially in the prosecution of corruption and complex financial crimes.

The State-Owned Companies Law (Law 13.303/2016) establishes the legal framework for state-owned and mixed-capital enterprises in Brazil. It regulates their corporate governance, including rules for the appointment of executives, procurement procedures and accountability mechanisms. In 2023, a supreme court minister issued a decision that suspended restrictions on political appointments to executive positions in state-owned enterprises (Richter 2023). As a result, political appointees were once again allowed to occupy high-level leadership positions, and the previously three-year quarantine period for individuals who had worked for political parties or electoral campaigns was removed. It was only in 2024 that the supreme court reversed this decision and reinstated the original provisions of the law (Richter 2024). However, the court did not suspend any political appointments made in state-owned enterprises in the period between 2023 and 2024.

The New Procurement Law (Law 14.133/2021) replaces the previous general legal framework for public contracting established by Law 8.666/1993. The provisions of the law became mandatory for all public entities in 2024 applying to the federal, state and municipal levels. The law introduces advances in transparency and integrity in public procurement. Among its innovations is the creation of the national public contracting portal (PNCP), which centralises contracting data from federal, state and municipal governments. It also establishes mandatory integrity programmes for large-scale contracts.

Regarding whistleblower protection, Law 13.608/2018 regulates the confidentiality of whistleblowers’ identities and allows financial rewards for information that supports investigations. However, it does not establish a comprehensive public policy or structured programme to protect whistleblowers (France 2019). The Clean Company Act incentivises companies to adopt internal reporting channels by offering reduced sanctions for firms that implement whistleblowing mechanisms.

Another significant gap is the lack of regulation for lobbying activities. Bill 1.202/2007, approved by the chamber of deputies in 2022, would represent an advance in this sense and, as of November 2025, was awaiting senate approval. It regulates the lobbying activities by establishing ethical principles, requiring the registration of lobbyists and demanding the disclosure of interactions between lobbyists and public officials. The bill also provides sanctions for non-compliance with these rules.

The president of Brazil recently signed an anti-corruption and integrity plan (2025- 2027)launched by the office of the comptroller-general (CGU). Among the priority actions established by the plan are: the expansion of the right to access public information in local government, the increase of transparency of public works in states and municipalities through the Obras.govportal and the promotion of social accountability in states and municipalities under the new PAC public works.

Institutional framework

Brazil’s network of accountability and anti-corruption institutions has been significantly strengthened since the early 2000s. From the period of re-democratisation until around 2014, there was a steady and incremental investment in accountability reforms (Da Ros & Taylor 2021). Subsequent investigations, operations and interagency cooperation exposed complex corruption schemes, demonstrating both the growing institutional maturity and the increased investigative capacity of these bodies. Interagency cooperation reportedly remains a challenge regarding, for instance, investigative abilities. Additionally, and despite the autonomy of major oversight institutions and their ability to act independently in corruption cases, political appointments and limited financial resources continue to pose challenges. These vulnerabilities create opportunities for political influence and constrain the institutional capacity of these agencies to effectively prevent and counter corruption.

Office of the comptroller-general (CGU)

CGU (controladoria-geral da união) is the principal oversight body within the federal government. Established in 2001 and restructured in 2003, the CGU expanded its roles to include transparency and anti-corruption initiatives, in addition to its original responsibilities for internal control, public auditing and disciplinary proceedings.

The CGU holds ministerial status, and its head is appointed by the president. There are concerns the absence of a fixed term and the possibility of dismissal at any time allow for potential political influence. Nevertheless, the institution is largely composed of highly qualified career civil servants and enjoys operational autonomy to conduct its work (France 2019). The CGU sets standards and provides capacity-building for oversight and anti-corruption practices across federal agencies. Regarding transparency across agencies of the federal government, the CGU monitors and ranks their performance in passive transparency (Painel da LAI) and active transparency (Painel Dados Abertos) through publishing open data.

It also supports state and municipal administrations in implementing control, prevention and transparency mechanisms. In addition, the CGU is responsible for enforcing the Clean Company Act, negotiating and monitoring leniency agreements, managing Brazil’s principal transparency portals and publishing public datasets on, for instance, sanctioned companies, disciplinary actions and related information.

Between 2003 and 2015,b5766c86876f the CGU conducted on-site audits in randomly selected municipalities. These audits provided a representative picture of corruption at the local level. Studies show that this initiative had a deterrent effect on municipal corruption. Beyond exposing and sanctioning illicit practices, the mere possibility of being audited discouraged public officials from engaging in corruption (Ferraz & Finan 2018). Moreover, incumbents identified as corrupt were more likely to be punished at the polls (Ferraz & Finan 2008). Because the audits were assigned randomly, researchers were able to estimate the causal impact of these anti-corruption efforts. Findings also indicate that, in addition to promoting transparency and accountability, the audits contributed to better municipal performance in the provision of public services (Funk & Owen 2020).

Despite its expanded roles and increased budget since 2003, the CGU still faces institutional capacity constraints. For instance, the institution remains understaffed relative to the scope of its responsibilities (Odilla & Rodriguez-Olivari 2021).

Federal court of accounts (TCU)

TCU (tribunal de contas da união) is an independent external oversight body responsible for assisting the national congress in monitoring the federal government's accounts. Its core functions include auditing federal agencies, evaluating the use of public funds and imposing sanctions for irregular expenditures. While the TCU operates at the federal level, each state has its own state court of accounts (tribunal de contas do estado) with similar responsibilities. Additionally, only five municipalities in Brazil have municipal courts of accounts. However, these local courts generally lack the same level of institutional capacity and performance as the TCU (Da Ros 2018).

The TCU benefits from institutional stability, a highly qualified staff of career civil servants and a secure budget. However, the appointment of its audit judges is made by both the national congress and the president of the republic, without fixed technical criteria. This appointment process leaves room for political influence (France 2019).

The TCU has played a crucial role in auditing and uncovering corruption and the misuse of public funds in public infrastructure projects. A recent audit reported that more than 8,000 public works projects were halted due to irregularities (TCU 2023). The court has also intensified its scrutiny of the current PAC programme, demanding greater transparency in the selection of infrastructure projects to be financed and executed (Truffi & Aguiar 2025). The TCU has also formally demanded that the government publicly present the values invested, the execution, selection criteria and performance indicators of the programme’s public works.

The president of the TCU holds considerable power, including the ability to decide which cases are prioritised for judgement. In 2022, the tribunal established the secretariat for consensus solutions (secex consenso), tasked with mediating debts, fines and other renegotiations involving major companies penalised for irregularities in public contracts, particularly in the area of public service concessions (Pires 2024). However, this new mechanism has raised concerns. TI Brazil (2025b) has criticised the lack of transparency surrounding these negotiations and the concentration of authority in a single oversight institution that simultaneously acts as mediator and guarantor.

Public prosecutor’s office (MPF)

Under the re-democratisation process and the 1988 constitution, the MPF (ministério público federal) gained autonomy and the responsibility to investigate corruption, including by launching criminal, civil and administrative proceedings. The agency has autonomy and budget to carry out its prosecutorial responsibilities.

The prosecutor-general is appointed by the president and approved by the senate every two years in what is often a highly political process (TI Brazil 2019). The National Association of Federal Prosecutors (ANPR) implemented a tradition of sending a list of possible nominees to the president, containing candidates approved internally. Lula was the first president to choose a name from the list, inaugurating the tradition in 2003 (MPF 2003). More recently, though, both Bolsonaro and Lula in his current mandate did not choose from the shortlisted names (Cury 2023).

Until Operation Car Wash, the criminal justice responses to corruption were considered insufficient. The results achieved by the task force, led mainly by the MPF and the PF, including the conviction of hundreds of politicians and high-level corporate directors, changed this finding (Da Ros & Taylor 2022).the results reflect the maturity of the anti-corruption frameworks and institutional capacities. On the other hand, leaked messages (the so-called Vaza Jato scandal) indicated that there was an unlawful close collaboration between the MPF’s federal prosecutors and the main judge of the operation (Londoño & Casado 2019). Additionally, the operation used controversial judicial tactics. Firstly, the task force made use of strategic management in the processing time of judicial proceedings, supported by margins of discretion and administrative autonomy. Secondly, the use of phone interception beyond the authorised periods and orchestrating arrests to force plea-bargain cooperation have been questioned (Rodrigues 2021). Finally, the main figures of the operation subsequently launched political careers, all combined to affect the task force (which was dismantled in 2021) and the institution’s legitimacy.

The federal police (PF)

Under the realm of anti-corruption and countering organised crime, the federal police is responsible for conducting investigations that involve federal crimes (that is, cases that involve federal funds or federal institutions), arresting suspects and handing them to the justice systems. Despite being subordinated to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, the institution has autonomy from the government since it is a permanent agency and cannot be dissolved (France 2019).

Over the past two decades the federal police gained investment and autonomy to investigate corruption. It significantly increased its personnel and budget. This institutional development led the PF to develop the proper expertise to counter money laundering and complex corruption cases through specialised anti-corruption units (OECD 2025).

Alongside the MPF, the federal police spearheaded Operation Car Wash, as well as the other anti-corruption operations in the country, by their direct action in criminal investigations. However, its status as a neutral enforcer has sometimes been questioned as it faces allegations of compromising procedural steps to gain public support (Rodrigues 2024). Additionally, during the Bolsonaro government, there were signs of political interference in the work of the PF and MPF, with political appointees and dismissals (TI Brazil 2019).

Judiciary

The Brazilian judicial system, especially the highest court, the federal supreme court (supremo tribunal federal, STF) has increased its role in corruption cases since the Mensalão case when the court convicted politicians for corruption for the first time. Conversely, it is also through the supreme court that significant setbacks in the anti-corruption frameworks have taken place.

The STF is composed of 11 judges appointed by the president and approved by the senate. Judges in Brazil enjoy independence and autonomy with stability and life terms guaranteed.

The role of the STF in the Operation Car Wash was primarily twofold. Initially, it did not restrict the main actors behind the investigation. However, since 2019 it has challenged some of these actors. The STF recognised the lack of impartiality of the operation’s judge and restricted the mandate of the MPF in Paraná to the deviation of resources involving Petrobras, meaning it could not work on other cases (Rodrigues 2024).

In 2024, an STF Justice, Dias Toffoli, through a unilateral decision, annulled evidence obtained within the scope of the leniency agreement signed with companies in Operation Car Wash. Additionally, the judge suspended fines and financial obligations arising from the leniency agreement that the companies had previously established with the MPF (Mendes 2023), and commentators cautioned that Toffoli had a conflict of interest with one of the defendant companies (Messick 2024).

Recently, a STF judge, Flavio Dino, has been vocal in promoting the transparency and traceability of budget amendments from deputies and senators. Recognising the multiple corruption cases arising from the allocation of these resources, the judge requested the creation of transparency mechanisms for the transfer of these federal resources for states and municipalities. Besides that, the judge mobilised the federal police to investigate misuse of these resources by legislators (Falcão 2025).

Financial intelligence unit (COAF)

COAF (conselho de controle das atividades financeiras) is the financial intelligence unit responsible for analysing and disclosing financial information related to possible financial crimes, such as money laundering, corruption and the financing of terrorism. As the main agency responsible for the prevention of money laundering in Brazil, it has as one of its mains activities the dissemination of anti-money laundering financial intelligence information.

It is an interagency council, created as a provision of the Brazilian anti-money laundering law (Law 9.613/1998) and is composed of a small staff, which coordinates information flows across the federal government (Da Ros & Taylor 2022). COAF produces intelligence analyses based on suspicious transaction reports submitted to the unit by financial institutions and other entities. Based on these intelligence reports, the competent authorities (such as the PF and MPF) decide whether to initiate investigations and whether it is necessary to break banking secrecy or gain access to other types of information through a court order.

In 2024, the unit produced more than 18,000 intelligence reports, made more than 25,000 exchanges of information with national authorities and more than 400 with financial intelligence units from other countries (COAF 2025). In a comparison, the unit produced around 4,000 intelligence reports in 2015 which shows the evolution of its institutional productivity. On the other hand, a recent study shows that the number of staff working in the unit remains below the needs required, specifically with the need to counter money laundering from criminal organisations operating in the country (FBSP 2025).

Since it was created in 1998, the COAF was subject to oversight from the Ministry of Economy. Concerns about political interference and its autonomy to conduct anti-corruption activities were raised in 2019 when the unit was transferred twice by the government – firstly to the Ministry of Justice and then to the Central Bank – and its former president was dismissed (TI Brazil 2019).

Other stakeholders

Civil society

Civil society organisations (CSOs) such as Transparência Internacional - Brasil, Transparência Brasil and Fiquem Sabendo, among others, are active in Brazil assessing and promoting transparency and integrity, monitoring and reporting violations and guaranteeing the right to access public information.

According to the civil society organisations map, there are almost 900,000 CSOs operating in the country (IPEA 2025). NGOs were often attacked and compared to a “cancer” by the former president Bolsonaro (Brito 2020).

Since 2019, Transparência Internacional - Brasil has been targeted what observers have characterised as a disinformation campaign, which culminated in an STC judge ordering an investigation into the CSO for alleged mismanagement of public funds (Messick 2024; Taylor 2024; TI Brazil 2025). Taylor (2024) argues that this investigation was “designed to intimidate Transparency International and its allies in civil society”.

The Brazilian civic space has been rated as “obstructed” by CIVICUS since 2018. In the 2024 monitor, murders of human rights defenders and Indigenous leaders were highlighted as serious issues (CIVICUS 2024).

Even though NGOs are free to operate in Brazil, activists and organisations working with indigenous lands and environmental crime – often closely related to corruption – are especially exposed to violence. Brazil was ranked as the second-most dangerous country in the world for environmental and land activists. In 2024, 25 activists were murdered: half of them were Indigenous and four Afrodescendants (Global Witness 2024).

Media

In Brazil, many corruption cases are uncovered by investigative journalists. Media outlets such as revista piauí and Folha de S. Paulo have investigated corruption schemes.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) characterises the Brazilian media landscape as highly concentrated in ten major conglomerates, belonging to ten families. It scores 63 out of 180 in the RSF’s media freedom index and has its lowest score in the political and economic indicators (RSF 2025).

In the past decade, over 30 journalists were murdered in Brazil. Investigative journalists who cover corruption are particularly exposed to danger (Freedom House 2025) and they are more threatened when located in small and medium-sized municipalities (RSF 2025). Journalism is particularly dangerous for women, corresponding to more than 90% of cases of violence against journalists in 2024 (Abraji 2024a).

According to the Monitor of Judicial Harassment against Journalists in Brazil, the level of judicial harassment against journalists has been increasing since 2020, with 654 lawsuits against journalists that can be characterised as strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPPs) (Abraji 2024b).

Brazil is also severely affected by disinformation. Disinformation campaigns often involve smears on journalists in attempts to delegitimise mainstream media and reporting (ICFJ 2025). Compared to other countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region, Brazil has one of the lowest levels of trust in news media, with 60% of respondents having “low or no trust” according to the OECD Trust Survey in LAC (OECD 2025b).

In 2023, the federal government created the National Observatory of Violence against Journalists with a reporting channel to monitor violent incidents against journalists. Recent evidence shows that the number of violent aggressions against journalists in 2024 (144 cases) was the lowest since 2018, but this still amounts to a serious threat (Fenaj 2024).

- This is discussed in further detail on page 29.

- The CPI ranks 180 countries and territories worldwide by their perceived levels of public sector corruption according to experts and businesspeople. The results are given on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

- This indicator measures the strength of public governance based on perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain (including both petty and grand corruption), as well as the capture of the state by elites and private interests.

- States and municipalities adopt their own legislative frameworks regulating conflicts of interest.

- Since 2016, the programme (programa de fiscalização de sorteio público) was reformed, and since then selects the municipalities to be audited according to their vulnerability and census data.