Query

Please provide an overview of anti-corruption and integrity standards for private sector blended financing instruments.

Caveat

In considering relevant standards for blended finance operations, this Helpdesk Answer restricts itself to international frameworks and principles; it does not cover national level regulations to which blended finance projects will be subject in different jurisdictions.

Introduction

As it has become ever clearer that the scale of investment needed to fund sustainable development around the world far outstrips the budgets of traditional institutional donors, blended finance has been hailed as a means to finance development in low- and middle-income countries (Collacott 2016). Governments and international organisations have increasingly advocated the use of blended finance to fill the ‘financing gap’ between current public spending commitments and target levels of investment needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (Tew et al. 2016).

The impact of COVID-19

The need to mobilise the vast resources needed to finance sustainable development has only been accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The public health crisis has generated an additional shortfall of US$1.7 trillion that low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) need to fund development, a gap now estimated to be in the range of $4.2 trillion annually (OECD 2020).

In response to the global health crisis, institutional donors prioritised pandemic-relief measures delivered via traditional aid modalities over more innovative forms of development finance such as blending. At the same time, commercial investors’ risk appetite took a hit during the pandemic, as they became less willing to take financial risks in frontier and emerging markets amid lowered expectations of profitability (Banque de France 2021).

Convergence – an organisation that describes itself as “the global network for blended finance” and seeks to promote private sector investment in LMICs – observes that blended finance flows were 50% lower in 2020 ($4.5 billion) than in 2019 (Convergence 2021). There is some expectation among analysts that COVID-19 will have a lasting impact on the blended finance market, and due to “tighter public budgets and the increased aversion of private investors”, blended finance instruments may not be an “appropriate tool in the short run” (Habbel et al. 2021: 13). Despite this setback, however, many OECD DAC members continue to establish and operate blended funds and facilities in an effort to leverage additional investment (Habbel et al. 2021: 5).

Supporters of blending argue that relatively small amounts of public resources can mobilise previously untapped sources of private capital through the use of innovative financial instruments that reduce perceived investment risk for the private sector. Amid the fervour for increased blending, critics have voiced several concerns. These range from the potentially distortive effects on local markets and the lack of alignment with national development strategies to the paucity of definitive evidence that blending contributes effectively to poverty alleviation (Analysis for Economic Decisions. 2016: 11).

Moreover, as yet, there seems to be an inability to leverage anywhere near enough private investment to deliver on the “billions to trillions” promise (Kenny 2022). Convergence (2021: 6) has found that the participation of commercial investors in blended finance instruments remains limited, with most private sector investors “tending to participate in blended finance on a one-off basis.” As such, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and bilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) remain by far the most significant type of investor both in terms of the number of commitments made and the value of investment (Convergence 2021:32).

Scale of blended finance and market size

The amount of assets under management in blended finance funds and facilities has grown considerably since 2017, although there was a noted drop in blended finance flows in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD 2022a). The annual blended finance capital flow has averaged about $9 billion since 2015 (Convergence 2021: 5). To date, Convergence has documented around 680 closed blended finance transactions, capturing 5,300 individual investments involving more than 1,450 investors (Convergence 2021: 6). Nonetheless, as a proportion of total ODA, the amount of public finance used in blending remains modest; less than 1% of total ODA was reported as private sector instruments in 2021, down from 2.2% in 2019 (Convergence 2021: 15).

This Helpdesk Answer does not seek to appraise the relative merits of blending; that remains a task for development economists, impact evaluators and academics.1028341fa639 Instead, this Answer considers the potential integrity risks of using public resources to subsidise private sector investments in LMICs, as well as measures to mitigate these integrity risks.

Integrity risks and investment risks

The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation – a major player in blended finance – defines integrity risks as “the risk of engaging with external institutions or persons whose background or activities may have adverse reputational and, often, financial impact”. This can include, but is not limited to, “corruption, fraud, money laundering, tax evasion, lack of transparency and undue political influence” (IFC 2017:2).

Investment risk on the other hand, refers to the potential loss inherent in an investment decision. A range of factors can threaten the profitability of an investment, including shifting political and market conditions.

These two types of risk are related. The risk of not achieving a return on investment could be heightened where there are insufficient safeguards to insulate that investment from corruption and fraud (Transparency International 2018: 7).

To date, limited attention has been given to integrity risks involved in deploying public finance to leverage further commercial investments as part of blended finance instruments. According to Jenkins (2019), this is concerning for two reasons. First, the participation of profit-driven actors such as impact investors, pension funds, commercial banks and sovereign wealth funds who may be unfamiliar with development assistance entails potentially novel integrity risks, such as conflicts of interest or inadequate due diligence procedures. Second, the complex financing arrangements, numerous intermediaries and multi-layered governance structures involved in blended finance projects may exacerbate potential integrity risks. This is because the involvement of multiple entities can make managing transactions and monitoring results difficult, which in turn can lead to opacity and a diffusion of responsibility that increases fiduciary risk and makes it less likely that corruption would be detected.

After providing a working definition of blended finance, the first section of this Helpdesk Answer considers principles and standards that are relevant to blended finance instruments, from both the public and private sector. The following part of the paper then considers integrity risks that could arise as a result of a misalignment between mandates, incentives and accountability systems between those entities involved. Finally, the last part of the Answer presents good practices that can help safeguard development funds from misuse when these are used to mobilise commercial finance and subsidise for-profit entities.

Definition of blended finance

Before proceeding, it is important to provide a working definition of blended finance and present a necessarily simplified overview of how it operates.

Numerous organisations provide various definitions, but at its core, blended finance is a means of structuring investments from organisations with different mandates, often with a focus on encouraging private sector participation in development financing (Pereira 2017).

The Transparency Working Group of the Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance (2020: 5) describes two categories of blended finance:

- “Blended concessional finance, which includes concessional finance from donors alongside DFI’s own finance; and

- A broader definition, which includes the use of development finance to mobilise additional commercial finance.”

As such, the narrower definition places emphasis on the concessionality of finance provided by the organisation with the development mandate, while a more expansive version of the definition includes the use of public finance to leverage commercial investments even where the public finance component is provided at market rates rather than on concessionary terms.

Concessional finance

As defined by the World Bank (2021), concessional finance refers to “below market rate finance provided by major financial institutions, such as development banks and multilateral funds, to developing countries to accelerate development objectives.”

When deploying concessional finance, the onus is on donors, multilateral development banks and development finance institutions (DFIs) to incentivise private sector players to participate in projects that would otherwise either offer below-market return on investment (ROI) or entail a high investment risk.

By offering terms that are better than those available on the open market, concessionary finance effectively offers a public subsidy to its recipients. The rationale is that providing a (temporary) subsidy can make an otherwise unviable investment possible, reducing the risk for other investors and thereby facilitating projects with a development impact that would otherwise not go ahead.

The incentives take the form of various financial instruments that can adjust the level of perceived risk or the rate of return for an investor. Such instruments are designed to incentivise investors to make investments in low- and middle-income countries they might otherwise deem ‘too risky’ for their specific asset class or portfolio preferences (Transparency International 2018). These instruments are thus believed to encourage the participation of partners that have not historically invested in low- and middle-income countries or development projects, such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and other commercial investors.

Another distinction is sometimes made between blended facilities that “only pool sources of capital which have a development mandate” and are typically managed by development finance institutions and blended funds, which also “mobilise purely commercial investors” and are most frequently managed by commercial asset managers (OECD 2021a: 9; OECD 2022a).

This Helpdesk Answer adopts the broader definition of blended finance, in line with the OECD’s description of blended finance as “the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional commercial finance towards the SDGs in developing countries” (OECD 2018a: 3).

Blending thus differs from traditional forms of development finance in that it relies on the involvement of the private sector and the projects it finances are at least partially commercial in nature (Transparency International 2018: 2). As such, a broad array of private sector stakeholders can be involved in different projects, including international banks and multinational corporations, local businesses and even private investment from individual households (OECD 2018b: 119). Private sector entities can be involved both as financiers investing in revenue-generating development projects, and as direct beneficiaries of investments channelled through blended finance initiatives (Kenny 2015). In both cases, the private sector investor or recipient expects to make a profit as a result of their involvement (OECD 2018a: 9; Romero 2016).

Types of blended finance instruments

Blended finance can encompass equity instruments, debt instruments, first loss capital, guarantees and insurance, development impact bonds, performance-based grants, structured funds and syndicated loans. For more information on each of these instruments, see Habbel et al. (2021) and Global Impact Investing Network (2018).

Relevant principles, standards and regulations

The fundamental intervention logic of blended financing is that it can generate returns on the capital provided by investors and shareholders while supporting projects with a “positive developmental impact” in low- and middle-income countries (OECD 2018b: 68). In principle, this dual obligation incentivises those developing blended finance projects, notably development finance institutions, to subject them to the same level of scrutiny they would get from commercial investors, while also encouraging them to take greater investment risks in projects that would otherwise not be commercially viable (Transparency International 2018: 3).

As such, there are three types of obligations that may be relevant for blended finance projects. First, those obligations derived from the specific blended finance principles and standards that have been established. Second, the aid effectiveness and risk management requirements associated with official development assistance. Third, the set of stipulations originating from or applying to the operations of commercial entities, such as anti-bribery and due diligence standards.

Blended finance principles and standards

The two most prominent standards are first, the DFI Working Group’s 2017 Enhanced Blended Concessional Finance Principles, and second the OECD DAC’s 2018 Blended Finance Principles and the associated Guidance Notes published in 2021 (see OECD 2021b).

The DFI Working Group’s Enhanced Principles were developed for operations that fit the narrower description of blended concessional finance and only for private sector projects. The five core principles are as follows (DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects 2017).

DFI Working Group Blended Finance Principles (DFI Working Group 2017)

|

Principle |

Description |

|

Principle 1: additionality/rationale for using blended finance. |

DFI support of the private sector should make a contribution that is beyond what is available, or that is otherwise absent from the market, and should not crowd out the private sector. |

|

Principle 2: crowding-in and minimum concessionality. |

DFI support to the private sector should, to the extent possible, contribute to catalysing market development and the mobilization of private sector resources. |

|

Principle 3: commercial sustainability. |

DFI support of the private sector and the impact achieved by each operation should aim to be sustainable. DFI support must therefore be expected to contribute towards the commercial viability of their clients. |

|

Principle 4: reinforcing markets. |

DFI assistance to the private sector should be structured to effectively and efficiently address market failures, and minimize the risk of disrupting or unduly distorting markets or crowding out private finance, including new entrants. |

|

Principle 5: promoting high standards. |

DFI private sector operations should seek to promote adherence to high standards of conduct in their clients, including in the areas of Corporate Governance, Environmental Impact, Social Inclusion, Transparency, Integrity, and Disclosure. |

In accordance with its broader definition of blended finance, the OECD DAC Principles are intended to cover operations that involve both concessional and non-concessional funds being combined with commercial finance for development.

OECD-DAC Blended Finance Principles (OECD 2018a)

|

Principle |

Description |

|

Principle 1: Anchor blended finance use to a development rationale |

All development finance interventions, including blended finance activities, are based on the mandate of development finance providers to support developing countries in achieving social, economic and environmentally sustainable development. A) Use development finance in blended finance as a driver to maximise development outcomes and impact. B) Define development objectives and expected results as the basis for deploying development finance. C) Demonstrate a commitment to high quality. |

|

Principle 2: Design blended finance to increase the mobilisation of commercial finance |

Development finance in blended finance should facilitate the unlocking of commercial finance to optimise total financing directed towards development outcomes. A) Ensure additionality for crowding in commercial finance. B) Seek leverage based on context and conditions. C) Deploy blended finance to address market failures, while minimising the use of concessionality. D) Focus on commercial sustainability |

|

Principle 3: Tailor blended finance to local context |

Development finance should be deployed to ensure that Blended Finance supports local development needs, priorities and capacities, in a way that is consistent with, and where possible contributes to, local financial market development. A) Support local development priorities. B) Ensure consistency of blended finance with the aim of local financial market development. C) Use blended finance alongside efforts to promote a sound enabling environment. |

|

Principle 4: Focus on effective partnering for blended finance |

Blended finance works if both development and financial objectives can be achieved, with appropriate allocation and sharing of risk between parties, whether commercial or developmental. Development finance should leverage the complementary motivation of commercial actors, while not compromising on the prevailing standards for development finance deployment. A) Enable each party to engage on the basis of their mandate and obligation, while respecting the other’s mandate. B) Allocate risks in a targeted, balanced and sustainable manner. C) Aim for scalability. |

|

Principle 5: Monitor blended finance for transparency and results |

To ensure accountability on the appropriate use and value for money of development finance, blended finance operations should be monitored on the basis of clear results frameworks, measuring, reporting on and communicating on financial flows, commercial returns as well as development results. A) Agree on performance and result metrics from the start. B) Track financial flows, commercial performance, and development results. C) Dedicate appropriate resources for monitoring and evaluation. D) Ensure public transparency and accountability on blended finance operations. |

Finally, the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation issued the Kampala Principles on Effective Private Sector Engagement in 2019. These principles focus specifically on private sector engagement via development co-operation at the national level (GPEDC 2019).

Kampala Principles on Effective Private Sector Engagement

|

Principle |

Description |

|

Principle 1 inclusive country ownership |

Strengthening co-ordination, alignment and capacity building at the country level |

|

Principle 2 results and targeted impact |

Realising sustainable development outcomes through mutual benefits |

|

Principle 3 inclusive partnership |

Fostering trust through inclusive dialogue and consultation |

|

Principle 4 transparency and accountability |

Measuring and disseminating sustainable development results for learning and scaling up of successes |

|

Principle 5 leave no one behind |

Recognising, sharing and mitigating risks for all partners |

As can be seen in the tables above, there is considerable overlap between these sets of principles. All contain mentions of transparency, but there is little in the way of operational guidelines that development practitioners can use to ascertain and mitigate potential integrity risks.

The Tri Hata Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance attempts to provide some specific direction. Developed by the OECD and various partners, it aims to provide “an international unifying framework for mobilising additional investment for the SDGs in developing countries” (see OECD 2022b). The work of its Transparency Working Group is particularly relevant to integrity and governance concerns. The Working Group issued a report in 2020 that underscored the need to (THK Transparency Working Group 2020: 6):

- “harmonise reporting practices through agreeing minimum reporting requirements for all stakeholders – and with an emphasis on public availability of information.

- Establish a common reporting standard for blended finance that will be fit-for-purpose and fit for all actors.

- Enhance access to information on existing blended finance facilities and investments.”

Aid effectiveness principles

As a form of official development assistance, all blended finance projects are expected to adhere to the principles of aid effectiveness set out in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, and the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation. Some of the core components of aid effectiveness set out in these frameworks are transparency, local ownership and consultation.

Accordingly, as noted by the OECD (2021c: 10), in line with the Busan Principles:

“information on the implementation and results of blended finance activities should be made publicly available and easily accessible to relevant stakeholders, reflecting transparency standards applied to other forms of development finance.”

Similarly, further guidance issued by the OECD (2021d: 8) states that:

“systematic consultation with local stakeholders is advantageous for blended finance deals. It should be inclusive and where possible bottom-up in order to increase the range of partners involved at community level as suggested by the Kampala principles. Such consultation helps ensure consistency with the country’s development priorities and ownership of results as well as provide the most desirable benefits to local beneficiaries.”

Anti-corruption safeguards and standards for development agencies and DFIs

Beyond the general principles developed for blended finance operations, there are a number of standards related to corruption risk management, due diligence and evaluation with which blended finance projects should comply.

Corruption risk management practices

Blended finance frequently involves the use of public resources to subsidise commercial entities at some risk that the investment will not be successful in generating either a profit or development impact. As such, unsuccessful blended finance projects represent an opportunity cost; donor resources used to support failed commercial investments could have been spent on more traditional forms of development assistance such as budget support or sectoral programming. Also in light of the often complex financial arrangements involved in blending, Transparency International (2018) therefore argues that blended finance projects should be held to the same high standard of corruption risk management as more other types of development assistance.

Most multilateral development banks apply the 2006 Uniform Framework for Preventing and Combating Fraud and Corruption to all their operations, including their blended finance activities. This framework commits the multilateral development banks to agree upon standardised definitions of corruption, strengthen information exchange during internal investigations and apply robust due diligence processes when lending to or investing in private sector entities. Research by Transparency International (2018) indicates that compliance staff at bilateral development finance institutions also tend to refer to the Uniform Framework as a guide.

Following the endorsement of the Uniform Framework for Preventing and Combating Fraud and Corruption in 2006, the focus of multilateral development banks’ anti-corruption efforts shifted to establishing a unified set of principles and guidelines to set out how these banks’ integrity offices should conduct investigations. These efforts led to the 2010 Agreement on Mutual Enforcement of Debarment Decisions, which was based on the following six principles (Seiler and Madir 2012):

- the adoption of harmonised definitions of prohibited practices

- the establishment of standardised investigatory procedures

- the creation of internal, independent investigative bodies and distinct sanctioning authorities

- the publication of written notice to entities and individuals against whom allegations have been made

- the use of the “more probable than not” standard when assessing alleged violations of integrity standards

- the recourse to a range of proportional sanctions to fit the nature of the violation

This collaborative process aims at increasing the cost of corruption in development projects by preventing a company found to be culpable of corruption by one development bank from obtaining contracts from another MDB.

Another important standard is provided by the OECD’s 2016 Recommendation for Development Co-Operation Actors on Managing Risks of Corruption. This recommendation stipulates that international development agencies are expected to establish a comprehensive corruption risk management system that includes codes of ethics, integrity advisory services, training, whistleblowing mechanisms, robust audit functions, risk assessment tools, political economy analysis, tough sanctions, co-ordination channels to respond to corruption cases and communication protocols in the event that corruption is detected (OECD 2016).

Naturally, many development agencies have established their own corruption risk management practices based on organisational exposure and need. It is important that these are based on up-to-date understanding of what makes these tools effective (Johnsøn 2015; U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre no date). Development agencies should diligently apply corruption risk management practices not only to traditional aid modalities such as grant-based programming or budget support, but also to more innovative forms of development finance, including blending. These should also be tailored to suit the particular configuration of the blended finance arrangement and factor in the whole range of possible intermediaries. Ex-ante corruption risk assessments related to a proposed blended finance project should also consider the impact on intended beneficiaries and affected communities, and make a concerted effort to understand any gender implications of the project.

Nicaise (2021) suggests that development agencies could also draw on ISO 37001 to assess the quality of anti-corruption mechanisms in pooled funds or blended finance facilities. This is a standard issued in 2016 by the International Organisation for Standardisation to “prevent, detect and address bribery”, and it provides a checklist of tools to ensure compliance of both private and public entities with applicable anti-bribery laws. Development agencies could choose to refer to ISO 37001 as a benchmark to guide due diligence assessments of third parties in blended finance transactions and develop a clearer understanding of potential corruption risks with regards to their partners and activities. According to Nicaise (2021), aid agencies could also recommend that blended finance facilities are subject to ISO 37001 certification to ensure that sufficient preventive measures are in place.

Due diligence on potential business partners and financial intermediaries

Another important corruption preventive measure is the thorough vetting of potential business partners and intermediaries in blended finance deals. According to research by Publish What You Fund, investing in financial intermediaries is an increasingly common activity for many development finance institutions, and for some of them accounts for more than half of their total investment portfolio (Anderton 2021).

The range of possible financial intermediaries is growing, partly as a result of blended finance projects intended to stimulate greater participation of new types of investors such as commercial banks, sovereign wealth funds, and pension funds in development assistance. In addition to the spectrum of investors, private businesses are often the beneficiaries of blended finance instruments (CDC Group 2018). Understanding the ownership structures of these entities and their level of political exposure is critical to minimise risks of tax evasion, criminal activity, money laundering and corruption (IFC 2017: 2).

According to Transparency International (2018), development agencies and DFIs engaging in blended financing should seek to acquire a range of information on potential business partners and clients as part of a rigorous ex-ante due diligence process. The OCED recommends that at a minimum, donors should screen potential partners’ corporate structures, business models and transparency standards (OECD 2021a: 17). Transparency International (2018) goes further, arguing due diligence should also include a risk review of politically exposed persons, criminal activities, civil proceedings and political influence. Additional due diligence is warranted when investments involve offshore financial centres (‘intermediate jurisdictions’) to ensure that these arrangements are not designed to facilitate illicit financial flows (Transparency International 2018: 10).

In addition, development agencies and DFIs should review partners’ ownership structures to identify ultimate beneficial owners. Research conducted by Transparency International (2018) suggests that many MDBs and DFIs only verify the ultimate beneficial owner above a threshold of 20 per cent or even 25 per cent of ownership or control. For entities that present a specific risk of money laundering and tax evasion, good practice suggests that either all owners should be verified or at least that the threshold should be much lower, around 10 per cent. Finally, when financial institutions or private equity funds are involved, it is necessary to conduct specialised reviews of these entities’ anti-money laundering frameworks (Transparency International 2018: 13).

Across all private sector engagement initiatives, including blended finance instruments, the OECD also recommends that donors vet potential partners in terms of their adherence to standards of responsible business conduct. The OECD (2021a: 19) points to its 2011 Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises as a reference point that can guide “donors in selecting blended finance partners with the highest possible levels of responsible business conduct.”

The OECD Guidelines are a multilaterally agreed-upon code of business conduct that encompasses standards in numerous relevant areas, including anti-bribery and corruption, competition, taxation, human rights and information disclosure (see OECD 2011). The OECD (2021a: 19) states that the principles outlined in the Guidelines “must be considered at the ex-ante stage of an investment, to ensure that the development rationale underpinning the intervention will be achieved in an ethical way.”

Operational guidelines to provide firms with pragmatic support on implementing these standards are available in the form of the 2018 OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (OECD 2018c). This Guidance could also serve as a reference point for development agencies seeking to appraise the integrity of potential investors, implementing partners and beneficiaries in blended finance deals, as well as to support enterprises to improve their integrity management frameworks (OECD 2021a: 19).

Thorough due diligence is an intensive process and not all development agencies and DFIs enjoy the networks and resources of the larger MBDs. This points to the need for institutionalised information sharing to ease the burden on individual donors. Transparency International (2018: 13) found that

“the lack of information exchange between multilateral development banks and DFIs has led to a capacity and capabilities gap between the institutions. On one hand, multilateral development banks do engage in information sharing activities, including exchanging lists of companies found to have acted corruptly, which are then mutually debarred from all multilateral development bank-financed operations. On the other hand, it appears that DFIs tend to have less contact with their counterparts, resulting in less capacity to respond effectively to emergent integrity risks.”

Likewise, a stocktaking exercise by the OECD (2018d: 7) found that bilateral development agencies and DFIs do not yet consistently promote responsible business conduct in their private sector engagement, which is a particular problem in the area of blended finance given that “commercial and development objectives are not automatically aligned.”

It is important to bear in mind that due diligence is not a one-off process. One potential business partners have been screened, potential integrity risks at the project level need to be monitored over the lifecycle of blended finance projects, particularly whenever the constellation of entities involved changes.

Evaluation standards

While not directly related to anti-corruption measures, harmonising evaluation standards and results metrics could help development practitioners to identify red flags that may indicate severe underperformance of a blended finance project, either through mismanagement or corruption.

Evaluating the impact of blended finance project is notoriously difficult (Winckler Andersen et al. 2019). Efforts have nonetheless been made in recent years to establish common evaluation standards in the blended finance and impact investing sphere. These include the OECD-UNDP Impact Standards for Financing Sustainable Development, the IFC Operating Principles for Impact Management and Measurement, and the IRIS+ metrics, as well as the OECD DAC Evaluation Criteria and Evaluation Quality Standards (Habbel et al. 2021: 15; OECD 2021c: 8).

The OECD-UNDP Impact Standards in particular are intended to support development agencies ensure accountability when working via development finance institutions as well as private sector intermediaries (Habbel et al. 2021: 22). In addition, The Tri Hita Karana Roadmap has sought to bring IRIS+ metrics into alignment with the Roadmap’s approach to measuring the impact of blended finance projects on the poor (Habbel et al. 2021: 22). Finally, some evaluation standards targeted at private sector fund managers, such as the SDG Impact Standards for Private Equity Funds, include transparency and governance as core assessment criteria (SDG Impact 2021).

Relevant regulations for private sector entities engaging in blended finance

In addition to the principles and standards set out above, there are a number of regulations applicable to private sector entities that need to be borne in mind by those implementing blended finance projects. These include anti-money laundering measures, banking regulations and measures to curb tax evasion. In addition to these harder measures, there are voluntary initiatives that could be considered, such as corporate social responsibility policies relating to environmental, social and governance factors.

Anti-money laundering

The literature on blended finance often points to financial sector regulation as a barrier to private sector investment in emerging markets. Along with banking regulations (see below), anti-money laundering regulation has been argued to “increase transaction costs for private investments in higher risk countries” (OECD 2021e: 23).

Nonetheless, the development mandate inherent to blended finance means that these types of investments are chiefly made in emerging and frontier markets, where development finance has high potential impact but is also exposed to severe integrity risks (Transparency International UK 2022: 2). As such, anti-money laundering measures are an important safeguard against the misuse of ODA.

The IFC (2017: 5) has recommended that where financial institutions are involved in blended finance deals, there should be an assessment to determine if the institution’s existing anti-money laundering mechanisms are legally compliant and contextually appropriate.

Core reference points are provided by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)’s International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism and Proliferation. Recommendations of particular relevance include Recommendation 10 on Customer Due Diligence, Recommendation 11 on Record-keeping, Recommendation 12 on Politically Exposed Persons, and Recommendation 19 on Higher Risk Countries (see FATF 2022).

Relevant FATF Recommendations (FATF 2022)

|

Recommendation |

Description |

|

Recommendation 10 on Customer Due Diligence |

Financial institutions should be required to undertake customer due diligence (CDD) measures, including: a) Identifying the customer and verifying that customer’s identity using reliable, independent source documents, data or information. b) Identifying the beneficial owner [...] For legal persons and arrangements this should include financial institutions understanding the ownership and control structure of the customer. c) Understanding and, as appropriate, obtaining information on the purpose and intended nature of the business relationship. Conducting ongoing due diligence on the business relationship and scrutiny of transactions undertaken throughout the course of that relationship to ensure that the transactions being conducted are consistent with the institution’s knowledge of the customer, their business and risk profile, including, where necessary, the source of funds |

|

Recommendation 11 on Record-keeping |

Financial institutions should be required to maintain, for at least five years, all necessary records on transactions, both domestic and international, to enable them to comply swiftly with information requests from the competent authorities. Such records must be sufficient to permit reconstruction of individual transaction |

|

Recommendation 12 on Politically Exposed Persons |

Financial institutions should be required to take reasonable measures to determine whether a customer or beneficial owner is a domestic PEP or a person who is or has been entrusted with a prominent function by an international organisation. |

|

Recommendation 19 on Higher Risk Countries |

Financial institutions should be required to apply enhanced due diligence measures to business relationships and transactions with natural and legal persons, and financial institutions, from countries for which this is called for by the FATF. |

Financial sector regulations

Institutional investors, including pension funds and insurance companies, have fiduciary responsibilities and as such must comply with certain regulatory requirements (THK Building Inclusive Markets Working Group 2020: 14). At the international level, financial sector regulations introduced in the aftermath of the 2007-8 financial crisis are reportedly perceived by industry insiders to act as a brake on cross-border blended finance transactions (Toronto Centre 2021: 5). The OECD (2021e: 23) points to the effects of the Basel III regulation on commercial banks and the Solvency II regulation on insurance companies as dampening enthusiasm among commercial investors for development finance. This is because these regulations impose high capital charges on high-risk investments in emerging markets and increased liquidity requirements.

According to the Toronto Centre (2021: 5), Basel III’s tough prudential standards restricts the ability of commercial banks based in donor countries to participate in guarantee structures, which is a common blended finance instrument in emerging markets. At the same time Solvency II could reportedly limit the ability of insurance companies “to outsource investment decisions and portfolio management to entities that are not regulated, such as development finance institutions or multilateral development banks” (Toronto Centre 2021: 6). However, a study by the Financial Stability Board (2018) on the impact of Basel III and Solvency II on private financing in infrastructure concluded that such financial reforms in G20 countries had only a limited impact on infrastructure finance in emerging markets. Nonetheless, domestic regulation may also impose additional restrictions on investors (THK Building Inclusive Markets Working Group 2020: 13).

Anti-bribery obligations

Private sector entities need to be aware of their anti-bribery obligations in emerging and frontier markets as more and more jurisdictions introduce tough regulations on foreign bribery (United Nations Global Compact 2016: 7). The 2010 UK Bribery Act, for instance, has required companies falling under its purview to proactively demonstrate that they have established “adequate procedures” to prevent bribery, thereby increasing corporate liability for corruption abroad (UK Government 2010).

Internationally, the landmark 1997 OECD Anti-Bribery Convention introduced legally binding standards to criminalise the bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions (see OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions 2009). Updates in 2009 and 2021 have encouraged signatory countries to incentivise private enterprises to establish adequate accounting arrangements, independent external audits, internal controls, as well as ethics and compliance programmes (OECD 2021f). This is complemented by the 2010 Good Practice Guidance on Internal Controls, Ethics, and Compliance, which is targeted at companies to support them improve the effectiveness of their integrity management systems (OECD 2010).

In certain jurisdictions, listed companies on financial markets are obliged to comply with certain anti-bribery requirements. In the European Union, for instance, since 2014 large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees such as listed firms, banks and insurance companies have been obliged to publicly report on their environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance, including in relation to anti-bribery measures (European Commission 2022). Since the introduction in 2021 of the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, this reporting obligation has been extended to all companies listed on regulated markets and the audit of reported information has become mandatory (European Commission 2021). Currently, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group is developing unified EU ESG reporting standards, and is considering a dedicated pillar on business ethics that would require companies to disclose information related to their anti-corruption and anti-bribery measures, lobbying, data privacy and compliance and conduct (EFRAG 2021: 101).

Voluntary measures

In addition to the regulatory obligations discussed above that may be pertinent to private entities engaging in blended finance instruments, there are also voluntary initiatives that can demonstrate a firm’s commitment to act with integrity. These include ESG criteria to which investors can refer as well as corporate social responsibility measures.

When choosing to invest in a blended finance proejct, institutional investors and governments alike may consider various criteria in their decision-making process, including environmental, social, and governance (ESG) indicators. Investors can align their investment principles with any of a host of international ESG frameworks. According to the OECD (2022a: 51), the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards are by far the most popular safeguard for blended finance funds and facilities, with 92% of those surveyed choosing to align their ESG criteria with those standards.

Other ESG standards include IFC Operating Principles for Impact Management, the UN Global Compact Principles for Responsible Investment, the Equator Principles, the Global Reporting Initiative, Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIRS), the International Integrated Reporting Council and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (OECD 2021a: 17; OECD 2022a: 51; Transprency International 2018).

The OECD (2021a: 17) suggests that these standards can be used as a benchmark to screen potential business partners and investment opportunities to ensure that blended finance funds and facilities only engage suitable partners.However, work by Transaprency International UK (2022: 4) suggests that corruption is “largely absent from leading ESG frameworks.” One notable exception is the Engaging on Anti-Bribery and Corruption Guide for Investors and Companies issued by the UN Global Compact 2016 Principles for Responsible Investment. At an absolute minimum, the North-South Institute recommends that any company convicted of corruption, fraud or criminal activity is excluded from participation in any partnerships for development (Carney 2014: 13).

Integrity risks in blended finance

There are several risk factors in blended finance operations that can lead to integrity breaches including corruption, fraud, money laundering, tax evasion and undue influence (IFC 2017: 2). First and foremost among these is a lack of transparency at both portfolio and project level. Other risk factors include the routing of transactions through offshore financial centres, the lack of necessary market expertise on the part of donors, tied aid, misaligned incentive structures, a dearth of participatory opportunities for affected communities and aid-recipient governments, as well as political exposure.

Opacity

The lack of transparency is a common lament among blended finance practitioners and observers alike. Private companies are not typically subject to the same level of scrutiny as public entities and firms may have legitimate reasons to not publicly disclose all the details of their operations. However, while blended financing involves bringing together entities that may have different transparency obligations, Convergence (2021: 6-7) observes that both public and private investors need to make drastic improvements:

“Concessional capital providers do not publicly disclose financial terms or ex-post development outcomes, limiting the evidence base for blended finance as a development tool, while private investors do not disclose data on financial performance due to confidentiality concerns.”

In response to the well-documented opacity in blended finance, The Tri Hita Karana (THK) initiative established a Transparency Working Group. This body has produced an operational definition of transparency in the domain of blended finance, describing it as (THK Transparency Working Group 2020: 5):

“the availability, accessibility, comprehensiveness, comparability, clarity, granularity, traceability, reliability, timeliness and relevance of both ex-ante and ex-post information regarding the use of public and private capital in blended finance transactions.”

In 2020, the Working Group published a report assessing the current state of availability of key data points related to blended finance. The study drew on insights from a survey of 30 blended finance actors ranging from private sector investors to DFIs, development partners and CSOs. Considering transparency across five different dimensions, the Working Group concluded that the transparency of blended finance instruments was unsatisfactory across the board. It found particularly problematic opacity in the areas of development impact, financial data on the value of the subsidy and details relating to financial intermediaries and the use of offshore financial centres (THK Transparency Working Group 2020).

Transparency status of blended finance across five dimensions

|

Theme |

Element |

Current State |

Risk |

Notes |

|

Project information |

Name |

|

|

Various databases exist that contain project information (such as the Convergence deal database) but there is scope to improve both quantity and quality of this type of data, particularly in relation to clarity (e.g. on location) and accessibility (e.g. public access). It could be feasible to use the IATI standard as a basis for this kind of information. |

|

Location |

|

|

||

|

Project description |

|

|

||

|

Financial elements (e.g. cost and funding types such as equity, technical assistance, insurance) |

|

|

||

|

Dates |

|

|

||

|

Status |

|

|

||

|

Development Impact |

Ex-Ante outcome |

|

|

Coverage on impact data is not consistent across actors and, where available, tends to be reported at the portfolio, not project, level. There is a valid discussion about whether stakeholders should prioritise process transparency (how impact is conceptualised) rather than data transparency (the quantitative impact of investments). |

|

Ex-post impact |

|

|

||

|

Theory of change |

|

|

||

|

ESG & Accountability |

Pre-project ESG reports |

|

|

There are several standards in the ESG space and comparability across them remains challenging, as well as clarity around which is being used by different actors. As a first step, greater transparency around the processes and standards, and how they were applied vis-a-vis individual investments, and how this translates to engagement with local communities, would enable a variety of stakeholders to better understand their opportunities for collaborating. |

|

ESG monitoring |

|

|

||

|

IAM/Complaints |

|

|

||

|

Value of instruments |

Subsidy figure ($) |

|

|

Data and information on concessionality remains scarce though donors are increasing requirements in relation to this type of information; the impact of this is yet to be fully assessed as it may present risks in terms of competition/ fair pricing considerations. Multiple datasets exist for data on mobilisation of private funds though differences in methodologies prevent comparability and consistent use. |

|

Subsidy rationale |

|

|

||

|

Mobilisation of private funds |

|

|

||

|

Financial Intermediaries & Offshore Financial Centres |

Sub-project information |

|

|

Information about the investments that financial intermediaries make using funds received from DFIs and other blended finance providers (sub-project information) is rarely disclosed, though typically guidance is provided about how such funds may be invested. Additional transparency in this area is considered medium risk, along with tax arrangements, because there is precedent for disclosure on both, whereas there seems to be a blanket refusal on beneficial ownership. In the case of tax arrangements greater transparency regarding both the rationale for certain arrangements, and what those arrangements are, is warranted. |

(THK Transparency Working Group 2020: 21)

Overall, it appears that the areas that pose the highest risk of integrity failures are also those with the highest degree of opacity. These areas are discussed in greater detail below.

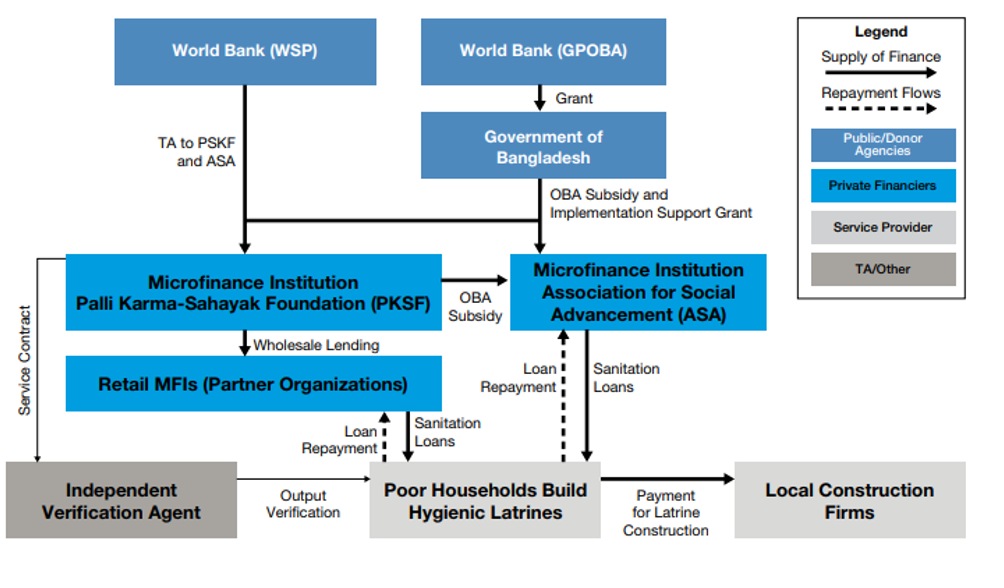

Financial intermediaries

The structure for mobilising and delivering blended finance projects is often extremely complex, involving multi-layered governance arrangements and numerous intermediaries (Transparency International 2018: 3). This is illustrated below in the schematic figure of a blended finance project in the sanitation sector in Bangladesh.

Figure 1

Source: World Bank (2016: 2)

The OECD (2018b: 65) has observed that the complex financing arrangements and governance structures involved impact the “management and perceived transparency” of blended finance, as monitoring the financial transactions and development results generated becomes difficult due to the sheer number of participants.

Corruption risk management also becomes more challenging when many intermediaries are involved. This is because the necessary risk management expertise varies from one entity to another, fiduciary risks can be transferred to entities without due consideration of their capacity to manage these risks, risk appetite can vary among stakeholders and where malpractice is identified some actors may seek to evade responsibility and look to others to take action.

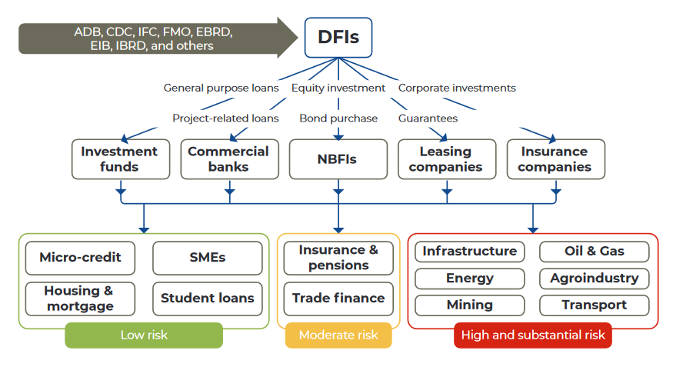

Opacity in relation to the role of financial intermediaries has been of growing concern to civil society observers in recent years. The graphic below demonstrates the range of actors that can be involved as financial intermediaries and the numerous financial instruments they can deploy.

Figure 2

Source: Publish What You Fund (2021a: 4).

Publish What You Fund (PWYF) points out that the presence of financial intermediaries is generally associated with “a lack of transparency [that] means that it is unclear where a great deal of this development finance ends up, the development impacts that it has, and the environment and social risks that it holds for project affected communities” (Anderton 2021). While some information is published about funds transferred by DFIs and other blended finance providers to financial intermediaries, data related to how the financial intermediaries then invest these funds (sub-investments) is virtually non-existent (THK Transparency Working Group 2020: 21; PWYF 2021a: 48). Indeed, PWYF (2021a: 17) found that only four DFIs published the names of private equity firms involved in sub-investments. The THK Transparency Working Group (2020: 21) also points to a “blanket refusal” on the part of entities involved in blended finance transactions to disclose details about their beneficial owner.

To some extent, this lack of transparency is accepted by blended finance practitioners as an intrinsic characteristic of working with private sector entities (Collacott 2016). Partly this is due to privacy regulations in the banking and investment industries, but also due to the insistence of firms on commercial secrecy (Habbel et al. 2021: 51). Convergence (2021: 50) speaks of an “inherent hurdle on the path to transparency” that arises due to the lack of incentive on the part of private sector investors to disclose performance data.

While acknowledging these limitations, transparency advocates nonetheless call for greater openness around performance and impact data. Groups like Publish What You Fund, The International Aid Transparency Initiative and Transparency International have sought to build pressure on DFIs and other concessional capital providers to strengthen transparency in their use of development funds and the financial terms they offer (Convergence 2021: 50).

The OECD (2021a: 20) likewise proposes that public sector players should challenge financial intermediaries who cite commercial confidentiality as a reason not to disclose data publicly, “based on the fact that trade secrets are not necessarily written in contractual agreements.” Indeed, Transparency International (2018) argues that given that DFIs deploy taxpayers’ money to reduce the risk for private investors and firms to enter a market, these companies should be expected to adhere to the same transparency standards as other ODA recipients.

There are also various economic arguments that have been deployed in favour of greater transparency. Collacott (2016) argues that information on the activities of investors and financial intermediaries needs to be made available to ensure that ODA being used in blending is complying with agreed standards of untied aid and that it is not generating any distortions in local markets. Commercial confidentiality alone should not be a pretext for opacity, and firms’ needs should be balanced against transparent and competitive processes to safeguard public resources. The OECD (2018b: 123) emphasises that “transparency regarding blended finance opportunities is decisive in establishing fair competition” and that a lack of transparency can undermine the impact of blending on development outcomes and market growth.

Not only will greater disclosure satisfy the public interest, but the academic literature indicates that companies that disclose more information about their integrity management systems enjoy increased investor confidence (DeBoskey and Gillet 2013; Firth 2015). In fact, investors increasingly refer to information on firms’ integrity management as an indicator of both risk profile and “potential for long-term value creation” (United Nations Global Compact 2016: 24).

Moreover, beyond the advantages for individual firms, excessive opacity is viewed by proponents of private sector engagement as an impediment to ‘scaling up’ blended finance, as it discourages other private entities from engaging in development finance (GPEDC 2019; OECD 2021a: 20). Convergence (2021: 29) emphasises that public disclosure of

“financial benchmarks, particularly when it comes to right-sizing and pricing risk-bearing concessional instruments, are fundamental to attracting more donors to the market because they bring clarity to investment structuring and outcomes.”

Despite this, Convergence (2021: 29) was unable to identify any donor or public investor that routinely discloses data on “investment amounts, instrument concessionality, direct mobilization figures, and impact.” As the authors of the study point out, the “lack of evidence on development impact and subsidies” weakens the case being made for blended finance by MDBs and DFIs for more ODA concessional funding to be assigned to these instruments (Convergence 2021 50).

Development impact and project level data

Given the opacity embedded at portfolio level, it is perhaps unsurprising that blended finance data is also very patchy at project level. One particularly glaring lacuna is that information on the varied impact of blended finance across different population groups is almost entirely lacking (THK Transparency Working Group 2020: 27).

A 2019 study by Convergence found that around half of blended finance transactions do not publicise the impact of the investment, and where impact is disclosed publicly, this is typically only at aggregate level in the annual report of the lead organisation (Johnston 2019).

Another report by the same organisation found that there is actually a downward trend in terms of the public disclosure of impact; while 51% of blended finance transactions in the period 2015-2017 “either do not report data publicly or have an unknown reporting status”, this figure rose to almost 70% in the period 2018-2020 (Convergence 2021: 50). A survey of blended finance funds and facilities by the OECD found that only a quarter of evaluation reports were made publicly available, with a majority of blended collective investment vehicles only sharing evaluation findings with their investors or internal management (Basile et al 2020).

As a result, in practice, blended finance projects are considerably less transparent than projects funded using other forms of ODA (ITUC 2016: 45). This opacity reduces the accountability of blended finance funds and facilities to their investors, donors, taxpayers, rival bidders, recipient governments and affected communities.

Tax avoidance and the use of offshore financial centres (OFCs)

The way financiers, multilateral development banks and DFIs or other donors channel funds to each other or to implementing partners in blended finance transactions can present another integrity risk. Without sufficient oversight of financial intermediaries, ODA resources can be vulnerable to tax fraud, transfer pricing for tax avoidance and the use of shell companies to misappropriate funds (Transparency International 2018).

Of real concern is the use of OFCs by several bilateral DFIs themselves, especially in light of the fact that many DFIs have weak policies on the use of tax havens (Vervynckt 2014). Some DFIs continue to advocate for the use of OFCs as necessary to enable DFIs to play a “catalysing role in attracting institutional capital” due to the lax legal framework in these jurisdictions and the ability to pool capital in a ‘tax neutral’ manner there (ITUC 2016: 37). OPIC, the US DFI, has required borrowers to establish “an offshore vehicle to facilitate the loan financing” (Kallianiotis 2013: 132). Most DFIs will use an OFC provided it complies with the OECD’s Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax purposes, and Carter (2017: 12) notes that many DFIs routinely route around 75% of their investments through OFCs. Particularly when channelling money into private equity funds, DFIs have traditionally chosen to use OFCs to avoid relying on “unpredictable and inefficient legal systems, and inadequate administration” in LMICs (Carter 2017: 8).

Given that OFCs deprive developing countries of much-needed tax revenues, some DFIs refuse to accept investment structures “whose primary purpose is subjectively judged to be the reduction of tax liabilities” (Carter 2017: 12). The THK Transparency Working Group (2020: 21) has recently called on concessional finance providers to, at a minimum, disclosure both the rationale for tax arrangements involving OFCs as well as with regards to the details of the arrangement themselves.

In light of the role tax havens play in facilitating tax avoidance and evasion and acting as conduits for the proceeds of corruption from low- and middle-income countries, Transparency International (2018: 9) argues that

“DFIs’ use of OFCs is in opposition to their development mandate. Moreover, the use of such jurisdictions constitutes an integrity risk in its own right, as it typically renders the investment more opaque, leaving little room for external scrutiny.”

Such concerns are reinforced by Counter Balance’s study of the EIB’s private equity fund investments in Sub-Saharan Africa. Counter Balance (2010) has criticised the Bank’s involvement with private equity funds domiciled in tax havens, as well as allegations of corruption among financial intermediaries and its lending practices to politically exposed clients.

These risk factors have been acknowledged by the African Development Bank (2019: 30), which notes that it is

“concerned by the involvement of Off-shore Financial Centers (OFCs) in financial transactions due to the heightened risks that OFCs can be used for dubious purposes, such as tax evasion and money-laundering, by taking advantage of a higher potential for less transparent operating environments, including a higher level of anonymity and the facilitation of opaque governance and cash flow structures.”

Lack of industry expertise

Managing complex financial instruments is no easy task. Providers of concessionary finance to blended finance facilities should be wary of rushing into the sector without understanding the market and its associated risks. The Habbel et al. (2021: 44) note that in industries and countries where development agencies and DFIs have limited experience with private sector engagements, they can struggle to correctly estimate the market entry risks private investors perceive. As a result, development actors may offer excessively generous concessionary rates and thereby waste public resources. Simply put, a lack of industry expertise on the part of the provider of concessionary finance can leave blended finance projects open to rent seeking by savvy commercial entities looking for subsidies they do not require.

In addition, while assessing the impact of a blended finance intervention at the end of the project cycle can help development actors to develop greater expertise, evaluations of blended finance projects “require evaluators with financial sector expertise, who are often difficult to find and more expensive” (Habbel et al. 2021: 12). The IFC notes that operating blended finance facilities requires specific expertise and considerable experience to identify the need for concessional finance, estimate the minimum level of subsidy required and assess whether the investment can generate a return to become self-sustaining in the medium term (Sierra-Escalante et al. 2019: 6). With the blended finance sector still relatively new, at present not all providers of concessionary finance have the requisite expertise to accurately determine investment and integrity risks. Research by Transparency International (2018) found that DFI compliance teams cited difficulties in securing adequate human resources to thoroughly vet potential business partners.

This can also apply to impact investors as well as public actors. According to Lewis (2022), some investors’ appraisals of “the risk of unethical business practices in investee companies […] may amount to a cursory check on the past history of company leaders.” A recent report by Transparency International UK (2022: 5) concluded that most impact investors do not sufficient prioritise anti-corruption considerations when deciding where to invest. The authors call on investors to go beyond only conducting due diligence on business partners to also study “business integrity risks in the operating environment… the adequacy of risk management capacity and level of commitment to mitigating these risks.”

Finally, incentive structures for blended finance practitioners may constitute an integrity risk factor. Some DFIs in particular operate in a broadly similar manner to private equity firms, which has implications for the way in which they incentivise their employees. While DFIs are meant to make investments in environments where traditional investors balk at the risk, DFI investment officers are often evaluated using the same performance metrics as traditional investors (such as deal flow and return on investment). Where the performance of investment officers is measured in terms of funds disbursed rather than development impact, Transparency International (2018: 11) suggests that they might be “less likely to conduct thorough ex-ante evaluations of project proposals, opening them up to greater integrity risk because of insufficient due diligence checks.”

Tied aid

When deployed by bilateral donors, blended finance can exhibit some of the characteristics of tied aid, whereby lucrative development contracts are restricted to commercial entities from the donor country. Bilateral DFIs draw much of their funding from their national governments, which often seek to further their own country’s interests when providing development financing. For example, the Italian DFI SIMEST has a stated goal of ‘promoting the future of Italy’, which in practice means that SIMEST generally makes investments in majority-owned Italian companies abroad (See CDP Group 2017). Evidence gathered by the OECD (2022c) indicates that tied aid increases the costs of a development project by between 15% and 30%.

The OECD (2021d: 9) concedes that “risks regarding tied aid could potentially be higher in case of blended finance”, and recommends that donors “should strive to remove the legal and regulatory barriers to open competition for aid-funded procurement.” Eurodad (2018: 4) argues that blended finance instruments should engage private sector firms on a competitive, open access basis by conducting procurement in local languages and advertising available opportunities in local media.

Where DFIs explicitly prioritise domestic companies through the use of institutional preferences for entities from the donor country, Transparency International (2018) suggests that there is a heightened risk that DFIs will face pressure to pursue projects that prioritise the interests of private investors from their home country over intended outcomes or the interests of affected communities. Transparency International (2018: 8) thus argues that:

“Where DFIs have a mandate to favour domestic firms, there need to be clear safeguards in place to ensure that blended finance programmes are not tailored to suit certain favoured firms as a result of collusion, behind-the-scenes lobbying or undue influence. Procedural transparency is therefore essential to ensure that external actors and affected communities understand why, when and how blended projects go ahead.”

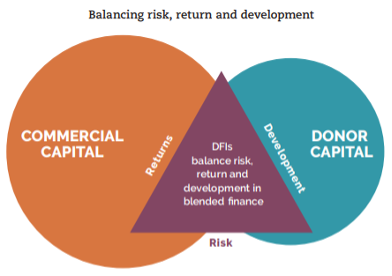

Figure 3: Balancing risk, return and development

Credit: Source: OECD (2018b: 71)

Managing misaligned incentives

A fundamental tension between balancing risk, return and development outcomes can expose blended projects to integrity risks. In theory, DFIs are often expected to manage these competing interests in blended finance projects. In practice, industry insiders have concluded that “the risks of market distortion and conflict of interest are inherent to blended finance” (Pegon 2019).

Helms (2018) argues that “embedding concessional funds in private sector investments can be fraught with moral hazard” because private fund managers are tasked with managing concessional finance provided by donors and investing these funds into other private enterprises. Where private sector entities both provide their own commercial finance and manage concessional resources provided by public actors, the Head of Blended Finance at IDB Invest notes that conflicts of interest can be “particularly acute” (Pegon 2019).

Some types of blended finance instruments are thought to be more vulnerable to moral hazard than others, with junior equity, subordinated debt and first-loss capital arrangements seen as structures most at risk (GIIN 2018: 3). That is because public donors’ resources take the greatest risk and absorb most losses in these types of structured funds, and these investment vehicles are often managed by commercial fund managers (Habbel et al. 2021). Sierra-Escalante et al (2019: 5) note that “conflicts regarding losses and payments” can arise between the providers of concessional and commercial finance when problems arise with an investment.

Moreover, the fact that in many collective investment vehicles “concessional finance is entrusted to private sector actors that may not have experience in managing public resources” only exacerbates the problem that commercial fund managers are likely to prioritise return on investment over development impact or public accountability (Sierra-Escalante et al 2019: 6; Romero 2013: 20).

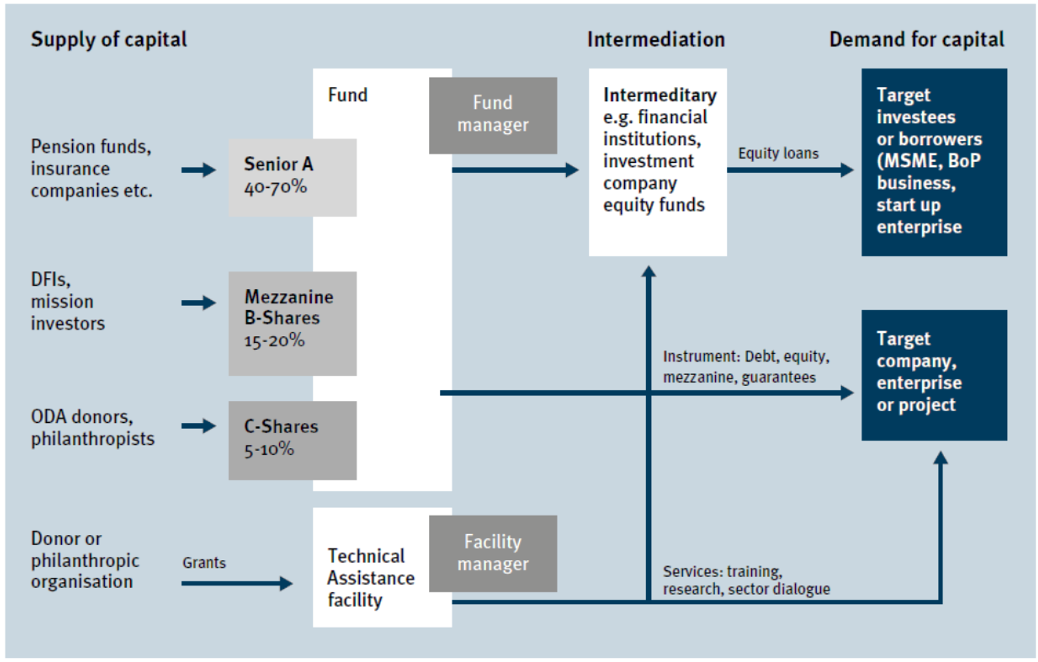

Figure 4

Credit: Source: Habbel et al. (2021: 19)

Public and private investors have different incentive structures when it comes to financing development projects. While non-commercial factors such as corporate social responsibility may play a role in private investors’ decision to participate in blended finance projects, they are also typically looking for a return on their investment (Transparency International 2018: 8). DFIs and multilateral development banks may be similarly profit-oriented, but unlike purely commercial entities they have a distinct mandate related to development outcomes, be this improved literacy, lower infant mortality rates, or better infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries.

Private sector entities have specific risk profiles in which they are willing to invest, and often that means investing in bankable projects in emerging, middle-income countries rather than those countries that would benefit most from the investment. As a result, projects might not align with pro-poor activities, instead focusing on middle-income countries and concerns of private investors (Collacott 2016; Pereira 2017). Recent criticism of UNOPS’ impact investing practices in India points out that the S3i business model “favour[ed] the relatively well off” (Kapila 2022; Ainsworth 2022). Mukesh Kapila (2022) claims that these kinds of projects pave the way for

“property developers who bring capital to construct smart high-rise apartments for richer people. These are obviously highly profitable ventures, even if they tend to make the poor homeless and force them to relocate to distant places which deprives them of their – already – precarious livelihoods.”

Transparency International (2018) argues that mixing the logics of profitability and development can lead to the emergence of divergent accountability and transparency dynamics, with a risk of potential conflicts of interests between investors and beneficiaries. This is implicitly acknowledged by the IFC, which observes that the implementation of blended finance projects “requires very strong governance […] so that markets are strengthened and that concessional funds are used judiciously” (Karlin, A. et al. 2021: 1).

Misaligned incentives between donors and aid recipient governments

In addition to potentially misaligned incentives between the public and private investors, another challenge can be competing priorities between donors and aid recipient governments (OECD 2021: 10). DFIs are not generally required to consult with recipient governments to ensure alignment between blended finance projects and national development strategies (ITUC 2016: 54-55). This contradicts the principle of national ownership of development assistance endorsed in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, the Accra Agenda for Action and the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation.

According to the ITUC (2016: 54), the result has been that many blended finance projects have tended to favour donors’ economic interests and western firms. There is also the potential for poorly designed blended finance project to generate market distortions in aid recipient countries. For instance, the IFC notes that DFIs could seek to offer more concessional financing that necessary to make a project viable to improve the return on investment for themselves or their project sponsors (Sierra-Escalante et al 2019: 3). This has the potentially to negative affect other market participants as well as competing providers of commercial finance (Sierra-Escalante et al 2019).

Incentive structures can also come into conflict where DFIs provide technical assistance in the same markets in which they are executing deals. If DFIs are responsible for both providing advisory services or capacity building to a government as well as investing in projects affected by that advice, serious conflicts of interest can arise (Sierra-Escalante et al 2019: 3). In these cases, DFIs are accountable both to beneficiary governments and to their own management teams. When conflicts between those accountability structures arise, the party providing financing (the management team) could potentially prevail at the expense of local interests and development impact. The IFC therefore recommends taking steps to separate investment and advisory teams within DFIs, establishing strict rules about information sharing between these teams and setting up robust processes to mitigate any potential conflict of interest (Sierra-Escalante et al 2019: 3).

Discrepancies can also arise when transparency and accountability standards in blended finance projects are lower than those stipulated by aid recipient governments for domestic public sector investment. Transparency International (2018) points to the example of Mexico, where all large-scale infrastructure projects above a certain financial threshold are required to be implemented with the involvement of CSOs and in line with the Open Contracting Data Standard. When comparable investments are financed by DFIs, such transparency requirements do not apply, and more decisions are reportedly made behind closed doors (Transparency International 2018: 12).

Political exposure and patronage networks

Private entities looking to profit from blended finance deals may look to exert influence over the selection or approval of projects by MDBs and public administrations. As well as lobbying for their own inclusion through legitimate channels, they may also seek illicit means of unduly influencing the design of a blended finance project, including backroom deals or kickbacks with officials and intermediaries to shape the way a potentially lucrative blended finance deal is structured. These risks are heightened where transparency is poor and consultation with intended beneficiaries is lacking.

Generally speaking, where corruption occurs it will likely reduce the profitability of a blended finance project. In other words, failure to achieve a return on investment may in some cases be attributable to corruption. If a project financed through blending is subject to a lacklustre due diligence process, then the risk embedded in the investment has not been appropriately priced (Transparency International 2018: 7). If investors do not have confidence in the way partners in blended transactions manage integrity risks, then they will require more protection against risk, perhaps through higher concessionary terms, making the overall cost of the project will be higher and jeopardising the principle of minimum concessionality.

Accountability mechanisms for blended finance

This final section of the paper synthesises accountability mechanisms and presents practices that could protect development funds from misuse when these are used to mobilise commercial finance and subsidise for-profit entities. Many of these safeguards are not especially novel, but rather relatively straightforward reforms, such as enhancing transparency and disclosure, improving due diligence and risk management practices, adjusting incentive structures and strengthening local participation and ownership. Oppenheim and Stodulka (2017: 6) point out that not only could these measures help to reduce integrity risks, but also have “an immediate and outsized impact on private capital mobilisation.”

Transparency and disclosure

There is broad consensus that enhancing transparency and disclosure related to both “ex-ante and ex-post information regarding the use of public and private capital in blended finance transactions” is a win-win for investors, donors and intended beneficiaries (THK Transparency Working Group 2020: 10).