The importance of asset recovery for development cooperation

One of the major innovations included in the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), signed 15 years ago in Mérida, is the principle of asset recovery (AR). Chapter V of the convention is dedicated to AR, with its opening Article 51 stating that parties to the treaty ‘shall afford one another the widest measure of cooperation and assistance in this regard.’ The idea is simple enough: when funds acquired through corruption are stored outside of the offender’s home country, prosecutors face the question of how to gain control over these assets and, ultimately, repatriate them. Their success then depends on international cooperation between authorities in the respective jurisdictions.

Asset recovery is intertwined with other global anti-corruption measures. Opportunities to take bribes or misappropriate funds will always be tempting as long as corrupt officials can store and enjoy their illicit wealth out of reach of investigators at home. Closing loopholes and freezing offshore accounts will not automatically rid the world of corruption, but efforts to address AR have the potential to influence officials weighing up the benefits and risks related to large-scale corruption.

This is partly why asset recovery has become an important issue for development cooperation. Moreover, many ill-gotten assets are deposited in financial centres that offer sophisticated banking and financial services as well as prime investment opportunities. In recent years, this dynamic has been described under the label of illicit financial flows (IFFs). Returning such funds to the countries of origin is then, typically, a matter of North–South cooperation.

Policymakers have responded to the challenges posed by IFFs and AR with a framework which comprises international commitments such as UNCAC as well as steps taken by individual states. Improving the effectiveness of the AR agenda must take into account the rather vague IFF concept on the one hand and development priorities on the other. Because such information is difficult to gather, figures which measure or estimate the volume of IFFs and assets being recovered must be treated with caution.

Main concepts and definitions

The concept of illicit financial flows (IFFs) refers to transfers of funds linked to illicit activities. As noted in a 2011 U4 Issue on the topic, either the funds in question must have been accumulated illegally or the act of transferring them must have involved criminal behaviour. The UN Economic Commission for Africas's (UNECA) 2015 report on IFFs notes:

‘These funds typically originate from three sources: commercial tax evasion, trade misinvoicing and abusive transfer pricing; criminal activities, including the drug trade, human trafficking, illegal arms dealing, and smuggling of contraband; and bribery and theft by corrupt government officials.’a31c1c77c7ca

Most often, the term is applied to scenarios in which funds are transferred across national borders. At the same time, the word ‘illicit’ implies a moral judgement but does not necessarily refer to clear legal criteria. IFFs might stem from acts of corruption, for instance when a political leader embezzles funds and transfers them to bank accounts abroad. Other IFFs involve the proceeds of fraud or organised crime. In those cases, the flows result from illegal activity.

A more expansive view of IFFs might, however, include earnings from behaviour that occurs in a grey area or is perfectly legal under local laws. Examples include tax avoidance by multinational corporations through base erosion and profit-shifting (as opposed to illegal tax evasion). In this paper, emphasis will be placed on illicit financial flows clearly connected to illegal behaviour.7cfe44dedab0

Asset recovery (AR) refers to the objective of gaining control over proceeds of crime by seizing them. When these assets are located in a foreign jurisdiction, AR can thus serve as a countermeasure to IFFs. Such processes take several steps. First, the assets in question must be identified and traced, which may involve cross-border cooperation when the funds are located abroad. Second comes the freezing of assets, which might again involve multiple jurisdictions. The third step is the completion of the procedures chosen in each case, which might be based on civil law (non-conviction-based forfeiture) or a confiscation that concludes criminal proceedings. This step of course depends on the gathering and – in cross-border cases – exchange of evidence. Finally, international cases raise the questions of if and how funds will be returned (repatriated) to the country of origin.

At each step, international asset recovery may involve requests for mutual legal assistance (MLA). If, for example, prosecutors discover that a former public official has moved funds derived from bribery to another country, they can send a request to that jurisdiction to have the associated accounts frozen. The AR process then involves a ‘requesting state’ (harmed by the official’s corrupt acts) and a ‘requested state’ (in whose jurisdiction the funds are currently located). Asset recovery does not always follow this pattern, but the terms of requesting and requested state are used throughout the literature.7c026068ac35

Another set of concepts relates to preventive measures in jurisdictions that offer investment opportunities for foreign clients. Individuals such as the fictional corrupt official mentioned above are called Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs), which the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) defines as:

‘Foreign PEPs: individuals who are or have been entrusted with prominent public functions by a foreign country, for example Heads of State or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, senior executives of state owned corporations, important political party officials.’79da80f62334

When financial institutions and related professions do business with such PEPs, their families, or close associates, the FATF guidelines advise enhanced due diligence measures due to the risk associated with such customers. Some publications refer to such requirements as ‘know-your-customer rules’: before entering into or expanding an existing business relationship with PEPs, financial institutions are asked to take precautions so as not to become a party to illicit financial transactions. Research literature and policy documents frequently note that such precautionary measures can be complicated to put into practice.

Part of the challenge is establishing a record of beneficial ownership. In our fictional example, the corrupt official could have transferred funds through a series of shell companies registered in multiple jurisdictions with different nominal directors. When a bank account belongs to a corporate entity that is itself owned by another, but neither of those is linked to the public official, the funds cannot easily be traced to their beneficiary. Such money-laundering tactics are often used to obfuscate the origins and ownership of assets. Records of beneficial ownership serve as a countermeasure by identifying a link between assets and the individuals controlling them.

The scale of illicit financial flows and asset recovery

Estimating the scale of corruption and related phenomena is notoriously difficult. In the early 2000s, for instance, it was estimated that corrupt officials in developing countries diverted US$20–40 billion annually. Such figures, as well as others attempting to express corruption-related flows as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), must be treated as rough approximations.7ef46d65ce1b The lack of clear-cut information is no surprise: corrupt behaviour is clandestine by nature, and there is no obvious way of gathering – let alone aggregating – data. Keeping these limitations in mind, let us consider several estimates for the scale of IFFs before turning to the data on asset recovery.

Estimating the volume of illicit financial flows

Since 2008 the non-governmental organisation Global Financial Integrity (GFI) has published regular estimates of the scale of IFFs with a focus on developing countries. Its numbers are based on publicly available data, with trade figures from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as the most important source. GFI attempts to calculate IFFs based on data regarding trade in merchandise goods. By analysing inconsistencies between national trade statistics, the GFI method creates a measure of financial flows based on falsified trade invoices:

‘The misinvoicing of trade is accomplished by misstating the value or volume of an export or import on a customs invoice. Trade misinvoicing is a form of trade-based money laundering made possible by the fact that trading partners write their own trade documents, or arrange to have the documents prepared in a third country (typically a tax haven) – a method known as re-invoicing. Fraudulent manipulation of the price, quantity, or quality of a good or service on an invoice allows criminals, corrupt government officials, and commercial tax evaders to shift vast amounts of money across international borders quickly, easily, and nearly always undetected.’7c89eec0f4ae

One downside is that this method cannot capture transactions in which both parties manipulate the same invoice, leaving no inconsistency between national statistics. The report further notes that not all discrepancies in trade statistics automatically translate into lost revenue for developing country governments. In addition, the numbers are based on aggregate data rather than pairwise information on bilateral trade flows, because such data is not universally available from the IMF and would be exceedingly difficult to use for calculations. Trade in services and intangibles, cash transfers, and hawala transactions are not included either, because no comprehensive data exists. Several plausible and potentially vast channels for illicit flows are thus not considered. This leads the authors to argue that their estimate is understating the extent of the problem.6559413e0915

Such methodological challenges notwithstanding, GFI estimates that US$620–970 billion was transferred out of developing countries in 2014. For the years 2005–2014, GFI claims that the average outflows reached 4.6–7.2% of the total volume of trade done by developing countries. The highest share of IFFs, by far, is attributed to China and other Asian economies.6d952ad173e4 Trade-related IFFs out of SubSaharan Africa account for roughly US$36–52 billion annually. Another US$63–91 billion is attributed to flows from the MENA region, including Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Other IFF estimates exist. In 2011, the African Union (AU) and UNECA commissioned the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa. In the resulting report, the panel’s chairman Thabo Mbeki notes that ‘our continent is annually losing more than US$50 billion through illicit financial outflows.’57fde9fc0ce7 In addition to illicit practices related to trade, the African report emphasises IFFs stemming from crime and corruption. The headline estimate provided for IFFs by UNECA, however, again relies on an estimation of trade misinvoicing.

Using UN Comtrade data rather than the IMF figures used by GFI, the AU–UNECA report suggests that trade-related IFFs from Africa amount to US$30–60 billion a year. Because the UN Comtrade data is sector-specific, the authors are able to point out that roughly half of these flows are related to extractive industries such as oil and the mining of precious metals.bfc488056853 In their most recent report, UNECA estimates that ‘during the period 2000–2015, net IFFs between Africa and the rest of the world averaged US$73 billion (at 2016 prices) per year from trade reinvoicing alone.’ebcc56d8e79f

To summarise, the literature on illicit financial flows offers three lessons. First, the figures cited in different publications are best understood as educated guesses rather than precise measurements:

‘Little reliable data is available, and each estimation method involves a large degree of speculation. No method can provide solid indicators of the scale of different channels and sources, or of trends over time or among countries, and all depend strongly on the input assumptions used.’c2a9d7245d3c

These methodological criticisms should not be taken lightly.d3b4f683f372 Researchers and practitioners interested in IFFs from an anti-corruption angle must pay attention to nuances in method and terminology. In addition to the overall uncertainty about the volume of IFFs, neither UNECA’s nor GFI’s publications provide a clear estimate of what share of IFFs stem from crime and corruption. While it makes sense to assume that corruption provides for a big share of IFFs in developing countries, it is not clear how this could be measured.70a6d078debe This is no surprise given the difficulty of coming up with a global estimate.

Simultaneously, corruption is linked to IFFs not just as a source of funds but also because corrupt behaviour facilitates other illicit flows, for instance when bribes are used to avoid prevention and prosecution.ef3270df78cc The resulting vagueness shows that disaggregated, country-specific approaches to IFF and corruption measurement might be more promising (Reuter 2017). In the meantime, researchers and practitioners must keep in mind that the IFF estimates offered by GFI and other sources do not represent (and do not claim to represent) estimates of flows related to corruption.

The second lesson is that virtually all observers agree that IFFs are a global phenomenon but are more damaging for developing countries. Despite the lack of precise measurements, multiple sources estimate that illicit financial outflows from Africa exceed debt and official development aid.2c62f990b74f The effects of illicit outflows are particularly harmful for developing states. In the short term, they might lose funds that could be used to provide public goods. Of course, the scale of IFFs cannot simply be equated with tax revenue, which also depends on factors such as assessment and collection practices.3aaf4eaf138d But a reduced tax base does not bode well for government revenues. Accordingly, governments that already struggle to balance their finances are particularly vulnerable to practices like tax evasion.9fd3ccab2147 In the long term, IFFs then become part of a vicious circle. The easier it is to channel the proceeds of corruption to foreign accounts, the greater the incentive for such behaviour – and the less trust will be put in domestic financial and political institutions. That is why Reed and Fontana argue that the negative effects of IFFs ‘are disproportionately felt in developing countries.’cc18e34c1704

Third, the concept of IFFs has been successfully used by advocates addressing corruption, money laundering, and taxation: ‘Large and confidently stated estimates of the scale of IFFs have played a critical role in attracting attention and encouraging political momentum.’88a2ad67991f In addition to AU and UNECA, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has endorsed the IFF concept. Among others, the organisation has published a report on the measures taken by member states to address the issue,dbc7bf11a342 which has been taken up by the responsible national agencies.80ff72f2cba9 Most recently, in October 2018, the Tax Justice Network Africa hosted its sixth Pan-African Conference, addressing the theme of ‘Corruption as driver of IFFs from Africa.’ As the section on policy responses shows, IFFs is a key term in debates about development and transnational crime.

Frozen? Confiscated? Returned?

As with IFFs, it is difficult to estimate the scale of completed and ongoing asset recovery efforts. No centralised mechanism exists to automatically aggregate information. Recent academic publications still rely on a list compiled by Transparency International (TI) in 2004 to illustrate the most significant cases of international asset recovery (Table 1). However, nobody knows exactly how much money corrupt political leaders have hidden abroad.e63f41d12693

Considering the scale of IFFs, stricter enforcement of anti-corruption and asset recovery efforts should be in high demand. As elaborated in the following section, recent years have seen a proliferation of international commitments and newly created tools to facilitate asset recovery. Yet despite the high issue salience since the early 2000s, it is not clear whether enforcement action has increased significantly.

Table 1: Infamous cases of grand corruption and asset recovery (Transparency International 2004, p. 13)

|

Head of government |

Allegedly embezzled funds (million US$) |

|

|

Mohamed Suharto |

President of Indonesia, 1967–98 |

15,000–35,000 |

|

Ferdinand Marcos |

President of Philippines, 1972–86 |

5,000–10,000 |

|

Mobuto Sese Seko |

President of Zaire, 1965–97 |

5,000 |

|

Sani Abacha |

President of Nigeria, 1993–98 |

2,000–5,000 |

|

Slobodan Milosevic |

President of Serbia/Yugoslavia, 1989–2000 |

1,000 |

|

Jean-Claude Duvalier |

President of Haiti, 1971–1986 |

300–800 |

|

Alberto Fujimori |

President of Peru, 1990–2000 |

600 |

|

Pavlo Lazarenko |

Prime Minister of Ukraine, 1996–1997 |

114–200 |

|

Arnoldo Alemán |

President of Nicaragua, 1997–2002 |

100 |

|

Joseph Estrada |

President of Philippines, 1998–2001 |

78-80 |

The World Bank and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) jointly created the Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative (StAR) in 2007. According to StAR’s data, the member states of the OECD have frozen US$2.6 billion between 2006 and 2012, but returned just US$423.5 million to the respective countries of origin.fbb33502b566 As the authors observe, this estimate is likely too conservative because many member states did not provide aggregate reports. Moreover, the data collection was limited to OECD members.

As noted in two reports on asset recovery prepared by StAR in cooperation with the OECD, many member states did not provide comprehensive information on law enforcement. Fourteen countries did not respond at all to the 2014 survey, and the remaining states often cited issues with data availability. Among this latter group, national authorities were often unable to differentiate between asset recovery and other proceedings, or they did not have national-level enforcement data due to their decentralised judicial system.3ffe161db9d7

At the time of writing, StAR provides online information on some 240 cases of international asset recovery initiated between the 1970s and the 2010s. According to its website, ‘the objective of StAR Asset Recovery Watch is to collect and systematize information about completed and ongoing (active) asset recovery cases that have an international dimension.’bafbddb432cc Each case is presented with a short summary of the parties and amounts of money involved, and links to sources. While the archive contains some cases of asset recovery related to foreign bribery, in which the primary targets are firms, almost 90% of the observations refer to individuals accused of grand corruption or embezzlement. Keeping in mind that some individuals such as Sani Abacha or Muammar al-Gaddafi are involved in several cases, while a few other cases do not identify the names of officials, the data refers to at least 90 different heads of state and other officials.

However, StAR does not have access to comprehensive data. To some degree, this is because even OECD member states – which enjoy high state capacity and rule of law – simply do not collect the relevant information. Other governments did not provide inputs in the initial survey, and/or they might have less information to begin with.

Asset recovery is not a top-down process conducted by some international body; instead, it depends on cooperation between agencies in different jurisdictions. The StAR data draws on expert research and voluntary self-reporting rather than automatic data transmission. In the surveys, governments might be more eager to report high-profile cases to create the appearance of good compliance. If World Bank and UNODC staff conduct their own research, they might be drawn to well-known cases or follow preconceived notions on where to look for new material. Much attention is concentrated on jurisdictions in which court proceedings are published online or routinely covered by English language media. Consequently, the snapshot offered by the StAR database is a somewhat imperfect view of reality.

Measuring the scale of asset recovery

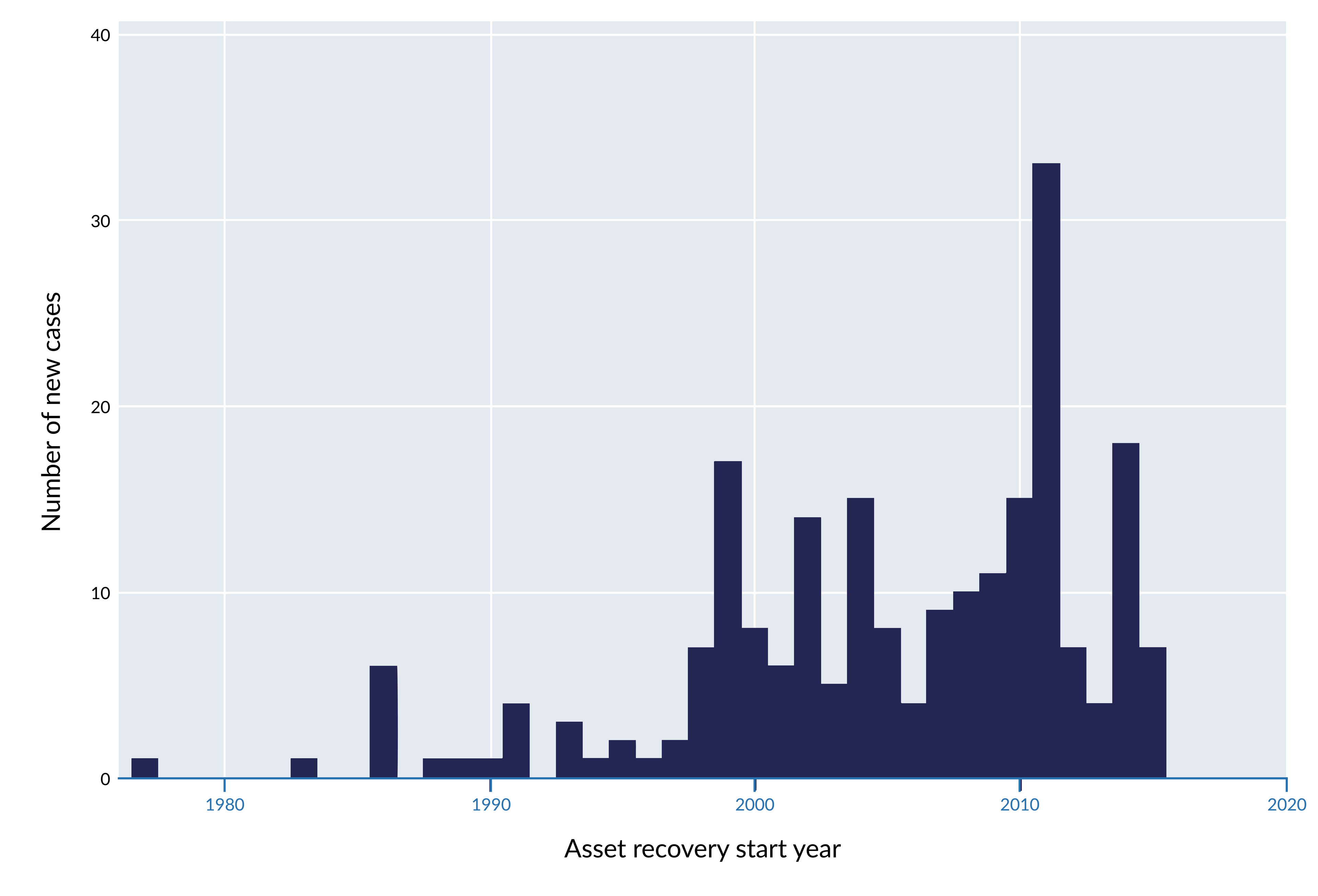

Key facts for all 240 cases listed on the StAR website as of April 2018 were gathered, with some minor corrections to fix inconsistencies in the data. Figure 1 plots the number of new proceedings initiated annually. Around the year 2000, AR appears to gain momentum. The increase in 2011 shows the surge of investigations in the wake of the Arab Spring. Yet apart from this event, the annual number of new cases has not continually grown since UNCAC entered into force in 2005. The room for growth suggests that there are obstacles to enforcement.

Figure 1: New asset recovery cases started per year (author’s calculation based on StAR database)

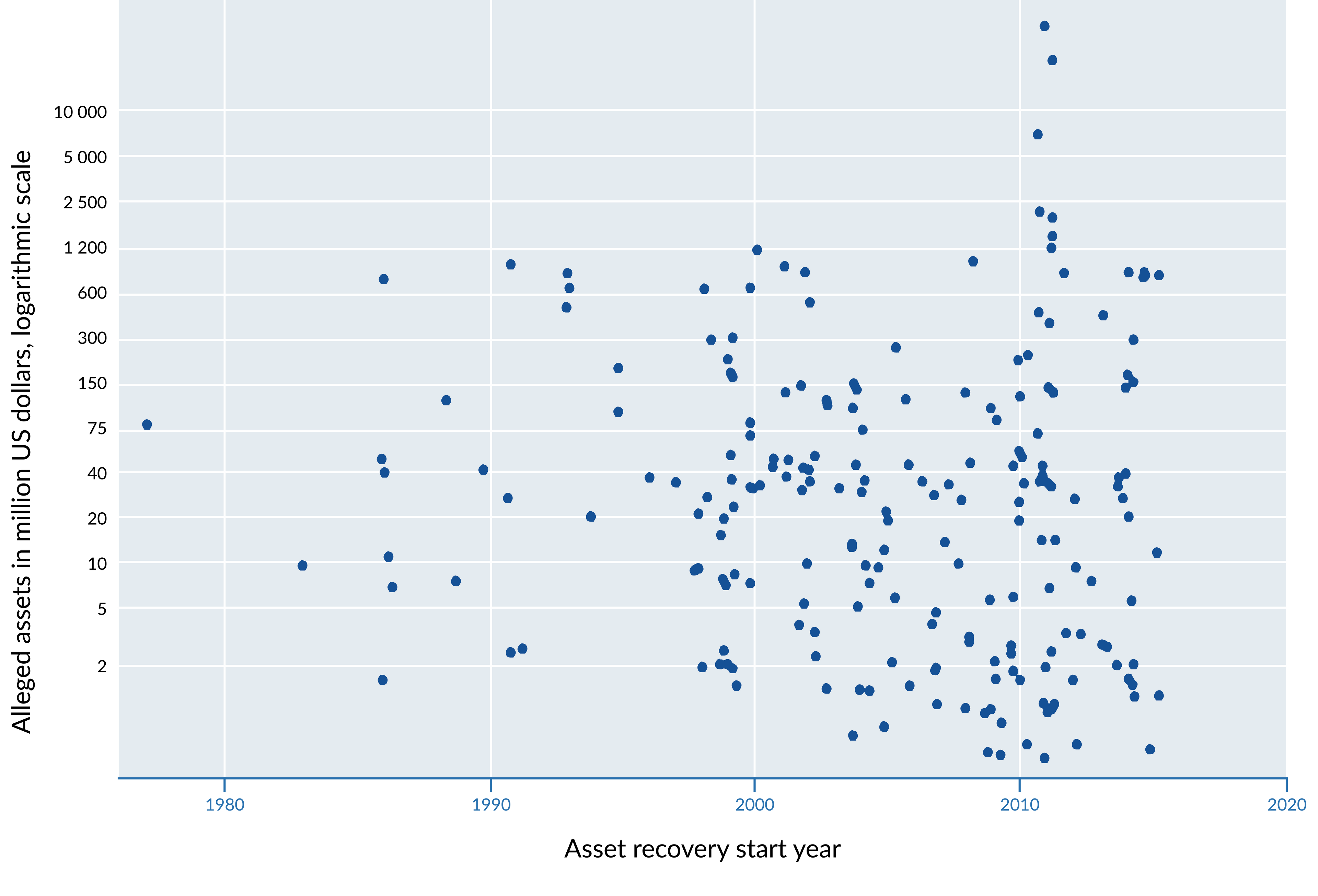

Figure 2 plots the amount of funds involved in each case of asset recovery, using the upper estimate when a range was given. To accommodate extreme values, the vertical axis is scaled logarithmically. Again, the proceedings related to the Arab Spring are outliers, reaching up to US$30 billion. Together, these figures show the massive scale of foreign assets under dispute: the mean value is US$450 million, with the median case still valued at US$22 million. Despite the moderate number of proceedings ongoing, asset recovery has the potential to make significant economic impacts, particularly for developing countries.

Figure 2: Alleged dollar amounts per case, scaled logarithmically for readability (author’s calculation based on StAR database)

Establishing the impact of asset recovery

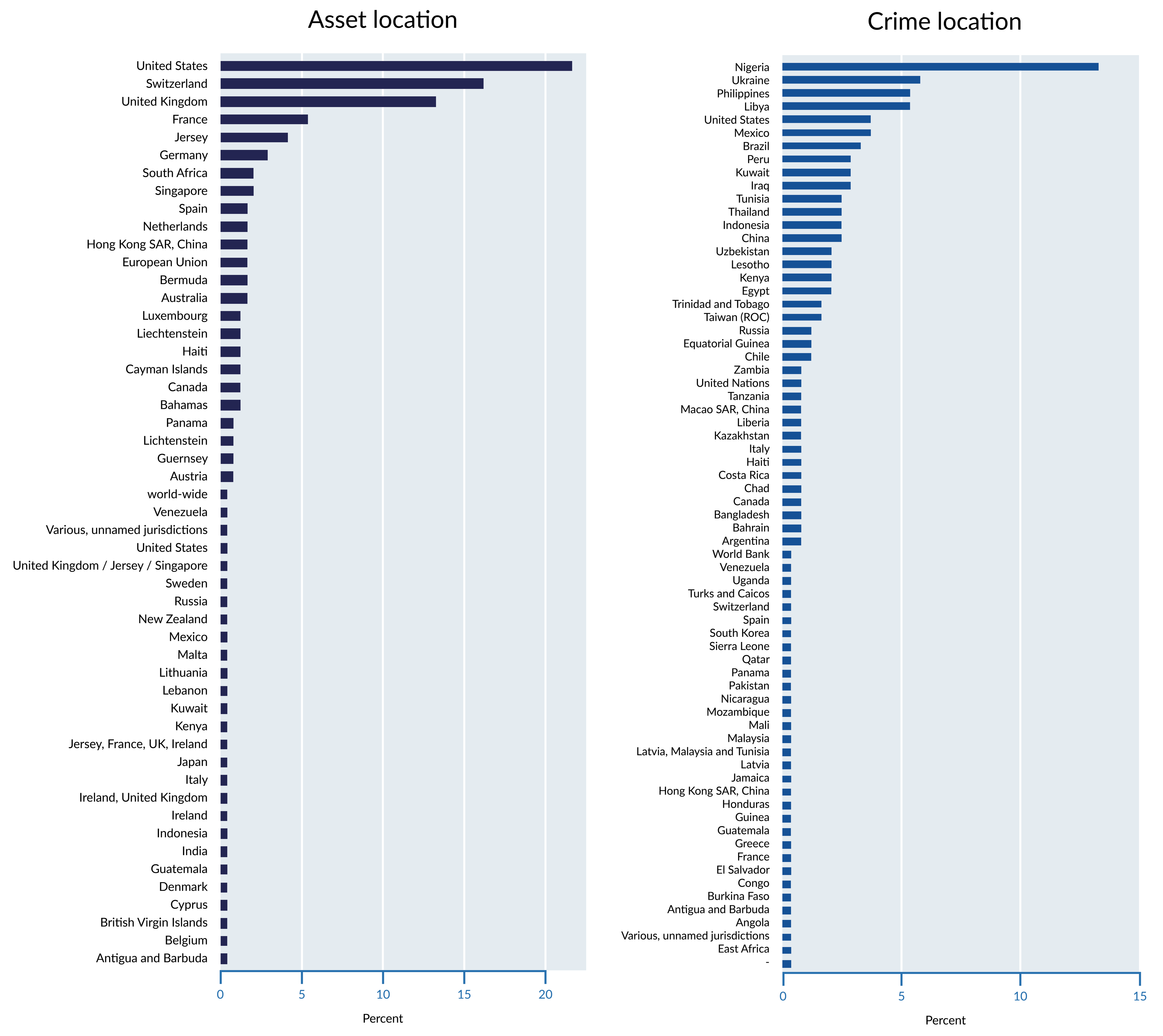

The potential impact of asset recovery becomes clearer when we consider that some countries are involved in many cases simultaneously. Figure 3 indicates how frequently states are named as locations of corrupt practices (‘crime location’) and as destinations in which illicit gains are invested or placed (‘asset location’). These numbers include duplicates in the StAR archive, so the number of unique cases for Nigeria, the Philippines, or Ukraine is lower. However, it seems clear that states from outside the OECD are the most frequent victims of large-scale corruption leading to asset recovery cases. Not counting some unresolved gaps, 65 different states show up as crime locations. Countries with high levels of corruption according to indicators such as the Corruption Perceptions Index5befd11d406b are featured prominently in this data.

However, other countries also suffering from corruption are absent from the list. Africa is often characterised as the region with the highest levels of corruption, and Nigeria tops the list in Figure 3. Yet only 17 of the 55 members of the AU (including Northern Africa) feature in the StAR archive. Either African cases are under-reported, or African governments are reluctant to pursue cases of grand corruption, or resource constraints are holding them back.

Figure 3: Frequency of countries as asset source and destination (author’s calculation based on StAR database)

The United States, the United Kingdom (including territories), Switzerland, France, and Germany are the top destinations among the cases covered in the database. This makes sense considering the size of financial and real estate markets in these countries. In addition, as already mentioned, this finding reflects the fact that the StAR data is skewed because data collection was focused on OECD member states. As with the list of crime locations, some plausible candidates are missing. Comparing Figure 3 to the latest ranking of 'financial secrecy jurisdictions,'43546358fcd7 several locations such as the Cayman Islands, Dubai, Taiwan, or the United Arab Emirates could be expected to show up more frequently in asset recovery. While these or other states could voluntarily report data to StAR at any time, they were not included in the initial drive to gather information.

Further research will be necessary to evaluate these findings. Unfortunately, the StAR database does not provide annual data on the number of completed cases and the amount of funds repatriated to the countries of origin. StAR provides information on the status of each case, but this is not necessarily up to date, and it is not clear whether the funds related to a ‘completed’ case have been transferred in full. Therefore it is difficult to tally the sum of repatriated assets. Sharman writes that the ‘total of looted state wealth repatriated as of 2014 is about US$4.5 billion,’130ebb9c3463 but his source does not contain this figure.

StAR remains relatively vague regarding the sums and the status of cases. A 2011 publication mentions an estimate of US$5 billion ‘repatriated over the past 15 years.’dcbb46ae64be The current annual report, however, refers to ‘approx. US$6 billion in stolen funds that have been frozen, adjudicated, or returned to affected countries since 1980,’ which implies a lower total of returns.ca91123f832b

Evaluating asset recovery efforts

Practitioners and researchers trying to get a sense of the status of asset recovery efforts around the globe face a sobering reality. There is some data on completed and ongoing cases, but it is incomplete, and many jurisdictions are missing entirely. It must also be noted that the increasing efforts to freeze funds do not automatically translate into their return. According to the data reported by the OECD and StAR, the volume of assets returned between 2010 and 2012 was US$147 million, and thus lower than the US$246 million returned between 2006 and 2009. The 2014 StAR report thus ends on a muted note:

‘Despite some efforts to advance the asset recovery agenda in a handful of countries, relatively few assets are being recovered and the amounts are far from the billions of dollars that are estimated stolen from developing countries each year. (…) There is much room for improvement and to make significant advancements in the asset recovery agenda.’83b674988aec

In other words, the sums transferred via successful asset recovery proceedings pale in comparison to the staggering estimates of illicit financial flows around the globe. This is to be expected because IFFs encompass a range of flows that are not subject to asset recovery. Nonetheless, it seems that corruption-related repatriation efforts are slow to gather momentum. Yet there are at least two reasons for cautious optimism. First, the StAR data points to many cases that are still ongoing, which could lead to substantial funds being returned in the future. Second, the political landscape has developed continuously both internationally and at the domestic level.

Global and domestic policy responses

Illicit financial flows and asset recovery sit at the intersection of multiple policy fields. Seen through the lens of development cooperation, IFFs affect the resources of vulnerable states while asset recovery might contribute to financing for development. Anti-corruption practitioners see IFFs as a symptom of corrupt behaviour, but also a part of problematic incentives for grand corruption. This perspective is closely linked to efforts to curb money laundering, terrorist financing, and tax evasion. This section addresses the most important building blocks of global governance in these areas and their relevance for IFFs and AR, and then discusses recent legal and policy developments in key jurisdictions – the United States, Switzerland, the United Kingdom – as well as in Europe more broadly.

International efforts to curb IFFs and recover stolen assets

International initiatives can be grouped into two categories. First, there are efforts under the auspices of the United Nations. The most recent are the targets to reduce corruption and illicit flows as part of the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This was preceded by the 2003 United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), which contained a strong commitment to asset recovery next to many other anti-corruption commitments. Second, the OECD spearheaded several initiatives to regulate transnational financial flows. Most relevant for the area of IFFs and asset recovery are FATF and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Sustainable Development Goals and Finance for Development

Anti-corruption reforms and measures to curb illicit financial flows are a core component of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (‘Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions’). Target 16.4 aims to ‘by 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime,’ while SDG 16.5 aims to ‘substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms.’ The inclusion of these good-governance goals has been hailed as a great success by anti-corruption activists.348d32e9b40c At the same time, observers are worried that the associated indicators might be problematic given the difficulty of acquiring valid data on such clandestine activity.ac3a74463ec7

The prominent inclusion of illicit flows and asset recovery on the development agenda underscores their salience and urgency. Here, the SDGs align with commitments in the 2015 Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. Items 23 to 25 of the Action Agenda set out the targets in more detail. According to the document, states will: strengthen national regulation and increase international cooperation on IFFs; tackle money-laundering risks by implementing FATF guidelines (see below) and other means; ratify UNCAC and turn it into an effective instrument; develop good practices on asset return; work on national transparency and accountability rules; and ‘strive to eliminate safe havens that create incentives for transfer abroad of stolen assets and illicit financial flows.’d3090411e6dc In 2017 and 2019, Ethiopia and Switzerland hosted two meetings of asset recovery experts and development practitioners to exchange best practices and coordinate their activities.7123051080b8

The Action Agenda also refers to the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa. It invites other regions to create their own estimates of IFFs. In addition, the document asks ‘the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the United Nations to assist both source and destination countries.’e59cb60a6cd8 This call for support resembles language used in the High Level Report, which is even clearer in the expectations towards OECD countries:

‘We found that while some developed countries were taking a firm stance against some aspects of illicit financial outflows, others had put in place institutional mechanisms that encouraged such flows and that could qualify them as financial secrecy jurisdictions. Apart from helping to establish a global norm against IFFs, non-African governments have a key role to play in assisting African countries acquire the capacities to fight the scourge of IFFs.’b64d5cd7e232

The goal of reducing illicit financial flows has thus been established on the global development agenda. At the same time, the IFF concept entails challenges regarding conceptual clarity and measurement. As a result, OECD members and developing countries may have diverging expectations about the relationship between IFFs and AR, and these challenges are considered in the final section.

UNCAC and StAR

The 2003 United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) is the crucial piece of international law designed to curb corruption, which also comprises many regional efforts with different priorities.07059a51edb1 With 186 states being parties at the time of writing, it is one of the most widely ratified international treaties. One of the core innovations in UNCAC concerns international asset recovery. According to Chapter V of UNCAC, ‘States Parties shall afford one another the widest measure of cooperation and assistance in this regard.’2e0c3261a2db This is developed in Articles 51 to 59 of the convention.

The provisions call for preventive measures along the lines of policies against money laundering (see next section), national mechanisms to confiscate property based on court orders issued in other states, and procedures to facilitate requests for legal assistance. Crucially, Article 57 of the convention calls for the return of confiscated assets to the requesting state. Taken together, Chapter V thus constitutes a strong commitment to the goal of asset recovery. At the same time, it leaves considerable room for interpretation ‘in accordance with the fundamental principles of its domestic law’ and ‘on a case-by-case basis.’ c8087e1c01ea58d6cdff5a67

In close cooperation with the UN, the World Bank has also begun to address asset recovery. The two organisations co-founded the Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative (StAR), which aims to support recovery efforts. StAR’s contributions broadly follow four lines of action. First, the initiative has published several practice-oriented guides on how to undertake recovery efforts, at times together with UNODC or under the auspices of the G20. These publications include a 2011 handbook for practitioners and a 2012 study on income and asset disclosure laws around the world. Another recent initiative provides country-specific guides on how to find the beneficial owner of assets in different jurisdictions.

Second, StAR aims to facilitate connections between national agencies and points of contact around the globe. Direct, working-level contacts between different authorities are crucial for the successful completion of mutual legal assistance procedures. Regional meetings have been held to support asset recovery after the Arab Spring and after the 2014 change of government in Ukraine. In December 2017, the first Global Forum on Asset Recovery brought more than 300 participants to Washington, D.C.153d33d75141

Third, StAR holds workshops and consultations with government representatives. As of 2017, ‘StAR has provided technical assistance to 43 countries and engaged with 106 around the world over the past ten years.’22c435650bae Finally, the initiative provides data useful for public awareness-raising and monitoring. Its online list of cases has already been introduced in the previous part of this U4 Issue.

Arguably, the efforts led by StAR will soon be boosted by UNCAC’s own monitoring mechanism. Since 2009, the anti-corruption convention is subject to a mechanism of peer review, coordinated by the Implementation Review Group (IRG). Its current cycle, scheduled to be completed in 2021, addresses the treaty’s provisions for asset recovery. UNODC officials have argued that the focus on Chapter V ‘will create unprecedented momentum for asset recovery, which will complement and continue the positive developments of the last years.’a7fef8af1179 Over the course of 2018 and 2019, the IRG has been discussing a set of ‘non-binding guidelines on the management of frozen, seized and confiscated assets.’28c49a90a0f0

Financial regulation and transparency

In addition to development and anti-corruption, global governance related to financial transparency is highly relevant for IFFs and AR. Money laundering and corruption form a ‘symbiotic relationship:’ money laundering allows corrupt actors to enjoy their ill-gotten gains by transferring them and making them appear legitimate; in more corrupt systems, in turn, it becomes easier to circumvent measures meant to stop money laundering. Consequently, attempts to curb either practice should factor in the other half of the equation.ccf55a11a518

The main international effort to address money laundering is FATF, founded in 1989. Its secretariat is hosted by the OECD but constitutes a separate entity. Since its creation, FATF has come widely known for producing recommendations relating to anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML/CTF), which grew from an initial 40 to the so-called ‘40+9’ recommendations. These are not binding international laws but guidelines for the group’s member states, which continually review each other’s performance. Implementation is supported by the Egmont Group, a network of national agencies designed to facilitate information-sharing.18ebeadbd30f Moreover, FATF is unique in that it monitors the compliance of non-members: since 2000, it has issued and updated lists of countries and territories whose legal frameworks and policies are not aligned with the recommendations, putting significant pressure on the affected states to reform their systems in line with FATF standards.45fe57177ace

Among others, FATF provides rules for financial institutions dealing with PEPs. With regard to due diligence, Recommendation 12 requires that financial institutions take three major steps when dealing with PEPs: always involve senior management, investigate to establish the source of the funds in question, and continually monitor the business relationship if they choose to proceed.2bdd3dfb5a2f Regarding beneficial ownership, Recommendations 24 and 25 urge countries to ensure that the relevant authorities can access information about the individuals in control of and benefiting from firms and other legal arrangements used to manage assets970b073eba93

These AML/CTF measures are largely meant to have a preventive function. The FATF guidelines prompt financial service providers in financial centres to vet their customers and improve record-keeping; this might deter kleptocrats from investing their money abroad. Such measures reduce the value of assets earned through corruption. As discussed earlier, this might be overly optimistic, and perhaps the more suitable analogy is one of increasing the costs of doing business with kleptocrats.

Beyond the preventive logic, however, regulations implemented to curb money laundering and increase financial transparency can help put asset recovery into practice. Obviously, tracing and freezing assets is only possible if they can be found. This is where due diligence requirements and registers of beneficial ownership come into play. While the FATF rules were not originally intended to address corruption, their broad scope is promising for activists, investigators, and prosecutors in this regard.

In addition to regulatory harmonisation at the national level, some initiatives provide means for self-regulation by the private sector. The most relevant case is the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) founded in 2003. After all, both IFFs and corruption are closely linked to the extractive sector (oil, gas, mining) in developing countries. EITI aims to prevent corruption by making financial flows related to extractive industries more transparent, allowing citizens to hold their governments accountable and curb bribery when it comes to bidding.f6ad6bd9b839 It is a multi-stakeholder initiative that involves governments (as implementers and/or supporters), civil society, and industry.

Initially, its relatively narrow focus on government revenue transparency excluded other aspects such as licensing negotiations.d193a79be0b1 The EITI standard was broadened over time, with the latest update in 2016.00103a1e886d As shown in a 2017 U4 Brief, EITI’s impact up until the recent change is unclear so far, with studies pointing to successes in agenda-setting but not development outcomes.7d639f973f79 Nonetheless, EITI and other initiatives to make revenues from highly lucrative industries more transparent can provide information pertinent to IFFs and AR.

Laws and policies at the national level

Given the nature of corruption and IFFs, policy responses must be implemented at the national level to be successful. This section summarises legal and policy developments in some of the most important jurisdictions as measured by their relevance for international banking: the United States, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the European Union. Given the scope of this U4 Issue, it would be impossible to analyse and compare all relevant cases over time. This overview does not aim to imply a ranking either. The goal is to provide information on success stories and remaining challenges in selected jurisdictions based on their importance and the availability of information.

United States

In the history of international anti-corruption efforts, the impact of US initiatives is second to none. American negotiators lobbied other OECD countries to commit to the banning of transnational bribery and played major roles in the drafting of regional and UN agreements. US efforts have been crucial to push the AML/CTF agenda through FATF and other venues, driven by the intention of curbing drug trafficking and terrorism. In other words, while the US agenda was not necessarily motivated by development goals, their initiatives have been influential in the fields of anti-corruption and financial transparency.591d7f679d9b Asset recovery is no exception.

The United States’ foreign policy and domestic regulation have unparalleled global reach due to its central position in global markets. For IFFs and AR, the US approach has a triple effect. It matters because the US is a crucial financial centre itself, hosting assets owned by foreigners who invest in American businesses, financial instruments, and real estate. Second, it matters because US regulation serves as a model to others, who strive to be in alignment to maintain business relationships. Third, as a result, the US government has a unique potential to prosecute offenders, exert diplomatic pressure, and threaten sanctions against non-cooperative governments.

American efforts regarding asset recovery rest on several initiatives dating back to the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations. The 2001 USA PATRIOT Act and its supporting legislation oblige financial institutions to conduct background checks on their customers. These laws provide the US Department of Justice with powerful tools to investigate and sanction the owners of ill-gotten gains at home and abroad. A team of experts from different departments of the US government began to specialise in corruption-related assets in 2003.97497c6a58ca Political momentum for such efforts came from the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI), which pursued and publicised several cases of large-scale money laundering – going after corporate actors that failed to comply with the legal requirements as well as high-ranking PEPs directly.0c6fde1ca8e7 The agenda has been further institutionalised with the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative, which was launched by the Justice Department in 2010 for ‘combating large-scale foreign official corruption and recovering public funds for their intended – and proper – use: for the people of [African] nations.’4493241c6a1e

While it is difficult to summarise the many cases prosecuted via different channels, US officials had ‘seized or restrained US$3.5 billion worth of corruption proceeds involved in money laundering offenses’ by the end of 2017.1c3322565717 This includes more than US$30 million of assets given up by the ruling Obiang family from Equatorial Guinea in a settlement with the Justice Department after a highly publicised legal battle lasting from 2011 to 2014. In a case against former Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha and his associates, US$480 million of funds were seized. Most recently, US prosecutors seized more than US$1 billion related to the 1MDB case in Malaysia.b88f25fa5537

Notwithstanding these encouraging results, proponents of asset recovery should not take continued success for granted. For one, sceptics might argue that high-level cases are bound to be influenced by politics. What prompted American authorities to start investigating Obiang Jr., who had been welcomed for years before? While many observers applauded the enforcement action, the question is whether prosecution is ‘politically dependent, or linked to U.S. foreign policy interests in the region.’b5172632405b

Moreover, considering how attractive the vast American market is for all kinds of foreign investors, many ill-gotten gains are likely to slip through the net of preventive measures. This is not just a matter of sheer size, but because of gaps in US legislation. Researchers comparing policies around the globe found it easy to create anonymous shell companies in Delaware and other key jurisdictions for corporate entities in the United States.fac741dcefc4 The USA PATRIOT Act, meanwhile, exempts real estate agents from due diligence requirements, leaving a loophole for those looking to keep a low profile.d359546a341e Thus, unparalleled power to prosecute offenders is at least partially hampered by political restraints.

Switzerland

Switzerland is an attractive destination for foreign assets and thus receives a high number of requests for administrative and legal assistance. Simultaneously, the Swiss government has been a major supporter of the international asset-recovery agenda, for instance by contributing to discussions at the UN. It is a main sponsor of StAR and supports the International Centre for Asset Recovery (ICAR) in Basel, which advises governments and holds workshops to train officials from different world regions to build administrative capacity for AR efforts. Since 2001, Switzerland regularly hosts the Lausanne Seminars, a forum to discuss the challenges of asset recovery, exchange information, and develop best practices.f26883a4d35f

Owing to a long history as a financial centre, Swiss authorities have gained experience with large-scale recovery efforts. An early case concerned the assets of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos (Philippines), whose Swiss accounts were frozen in the 1980s. The legal proceedings leading to their (partial) return lasted well into the 2000s and have been widely discussed as a watershed moment.524e9297a984

Other high-profile cases centred on Swiss banks and authorities include those of Sani Abacha (Nigeria), Vladimiro Montesinos (Peru), Mobutu Sese Seko (DR Congo), and Jean-Claude Duvalier (Haiti). Altogether, Swiss authorities estimate to have restituted approximately U$2 billion in assets. Yet the Mobutu and Duvalier cases underline the difficulty of AR: decades of proceedings failed to produce significant repatriations, not least because authorities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in Haiti did not complete their part of the necessary procedures. More recently, Swiss authorities were quick to freeze several hundred million US dollars related to the Ben Ali (Tunisia), Mubarak (Egypt), and Yanukovych (Ukraine) estates.ae69e02d0fbb

Thanks to the lessons learned from past cases, ‘the Swiss have perhaps the most “victim-friendly” asset recovery laws of any state’ paired with the ‘political will and technical skills to make [them] work’.d4758aa0820c In 2016, the Foreign Illicit Assets Act (FIAA) entered into force. It facilitates the freezing and return of assets linked to countries lacking the conditions to conduct their own investigations. To this end, the FIAA allows for the non-conviction-based confiscation of assets through administrative procedures; the Swiss financial intelligence unit can also provide foreign counterparts with data on the Swiss assets of PEPs. Both provisions do not require prior requests for legal assistance, allowing Swiss authorities to take proactive steps.6654b17fd058

The FIAA supersedes the 2011 Restitution of Illicit Assets Act (RIIA), which first codified Switzerland’s progressive approach based on the experiences with Duvalier and others. The RIIA already gave Swiss authorities a mandate to target foreign PEPs. It also formalised the assumption that assets are likely unlawful if they are disproportional to the official earnings of foreign government officials. That way, Swiss law provides a backup solution to seize assets even if no requests for mutual legal assistance are filed, for instance because the country damaged by corruption does not have the necessary resources or political will.e909d38230be

Yet despite the progressive stance taken by the Swiss government, which has had a dedicated federal strategy for AR since 2014,766e2a1714bc some limitations remain. Financial transparency and AML/CTF rules are strong on the books – but unlike their American colleagues, Swiss authorities cannot apply punitive sanctions or expensive settlements.afb50efcea02 In September 2018, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) merely criticised a big bank for repeated failures to comply with AML rules in cases related to the Petrobras and FIFA scandals.031fc5600e4f Similarly, the banking supervisor had criticised how major banks handled the affairs of PEPs in the context of the Arab Spring. No significant sanctions were applied in these cases. Such a gap in the Swiss system to promote financial transparency seems problematic.863779418e46 Others have pointed out that Swiss authorities have begun to use tax-related information exchanges to address IFFs, which could be expanded further.81cb0c589f7f

United Kingdom

In recent years, UK governments have underscored their will to address corruption both through their development agenda and financial regulation. With the adoption of the 2010 Bribery Act, British law against bribery in foreign business transactions is now even tougher than the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).0d13a2f0e037 The 2016 London anti-corruption summit, spearheaded by David Cameron, brought together many high-level officials and produced a list of individual commitments to address corruption worldwide (Transparency International 2016).

The UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) has gained experience with anticorruption work as well as asset recovery. It has achieved a unique status by successfully arguing that measures to prosecute kleptocrats would amount to efficient development spending. A dedicated ‘International Corruption Group’ was created in 2006 under DFID leadership and later integrated into the National Crime Agency (NCA). This group, spurred by revelations about Nigerian ill-gotten gains located in Britain, has pursued several cases leading to significant assets being frozen.bad987cc5894 Penalties arising from foreign-bribery cases have also been used to benefit development goals, such as in the case of BAE Systems paying £30 million for education needs in Tanzania.c9383b2c6ed5

Moreover, the United Kingdom has adopted new laws with significant potential to address money laundering and kleptocracy. Its new Criminal Finance Act entered into force in October 2017, introducing the concept of Unexplained Wealth Orders (UWOs) into civil law. With this measure, courts can oblige PEPs to provide documents about the origins of their assets in the United Kingdom. Serving their first-ever UWO, a British court recently asked an Azeri state banker’s wife to explain how she could afford London real estate and shopping habits that far exceed her husband’s official salary.7c16e7bbb10849fc2944df52

The UK also leads the charge to establish national registries of beneficial ownership, recording not just the officers and legal owners associated with corporate structures but also their ultimate beneficiaries. Such registers exist for companies and for real estate.0910d998c954 However, the responsible government agency hardly has the resources to monitor compliance and does not order punitive fines if it discovers problems. Ironically, the first-ever legal action in response to false information being filed was against someone trying to point out the lack of oversight in the system for company registration.d43d34162513 In addition, the NCA has only a modest budget to conduct investigations on IFFs. A recent media report concludes that ‘Britain’s response to the threat posed by illicit financial flows has so far been more thundering rhetoric than meaningful action.’35b0a16fa771

Several issues remain hotly debated. One concerns the British Overseas Territories (OTs) and Crown Dependencies (CDs), which have a reputation as secretive jurisdictions for foreign investments. These territories are formally independent but remain aligned with British policy in practice. Regarding beneficial ownership registers, new UK legislation obliges OTs such as the Cayman Islands to make their registers accessible to the public by the end of 2020. Yet the CDs (Guernsey, Jersey, Isle of Man) are exempt from this rule.c91d1ce7ef90 Moreover, recent work by TI and partner organisations emphasises other vectors for IFFs into the country. A particular form of corporate structure (Scottish limited partnerships (SLPs)) has been linked to approximately US$80 billion from Russia flowing into the UK.0847a0457dcf

A second hotspot is real estate – with London as the most attractive (and expensive) market for foreign buyers, who routinely use corporate vehicles to handle transactions. Research by TI and Thomson Reuters indicates that hundreds of foreign PEPs own property in London through firms registered in secrecy jurisdictions, thus undermining the goals of the ownership register.0d6e70e735c0 If some of those funds can be linked to corrupt practices, UK authorities may dramatically step up enforcement in the next few years. Yet many of these arrangements might be driven by the desire to avoid taxes, not money laundering to conceal corruption.8492f51bed84

European Union

Several EU member states have become active regarding IFFs and asset recovery. France is highly relevant considering its close ties to many African governments and its attractiveness as a destination for foreign capital.40e1db4f6df1 Following a trial in absentia, a French court recently ordered the Obiang family to give up ownership of a vast mansion in Paris ‘as well as a fleet of fast cars and artworks, among other assets.’91f82dfa5da8 The French case against the Obiang family is not one of legal assistance to a successor government. Instead, anti-corruption activists from France and Equatorial Guinea initiated civil-law proceedings in the jurisdiction hosting the dictator’s assets, prompting French authorities to become active.4126d372b987

Germany, as the EU’s biggest market, has begun to adopt the IFF perspective in its development agenda.dd692f428d1d When it comes to financial transparency and AR, however, German laws and administrative practice have been criticised.9fd9df252674 Investigation and prosecution of economic crimes is highly decentralised. Regarding bribery of foreign officials, some local prosecutors have been found to be much more active than others,18a551b3628a which suggests similar challenges for asset recovery. New criminal-law provisions on asset recovery were introduced in 2017.d71dc4c92d3a Overall, however, Germany and France appear marginalised in the academic literature. Given their weight as financial centres and foreign-policy actors (particularly in Africa), future research should look at the activities of the largest EU members.

The European Union itself, meanwhile, affects the IFF and AR agenda in two major ways. First, European regulations complement the FATF and other initiatives dealing with money laundering and financial transparency. The EU has issued six directives to curb money laundering, which oblige member states to create rules and procedures in line with FATF recommendations. However, this impetus for harmonisation towards progressive rules is somewhat hindered by the mechanisms for supervision: national authorities remain in control of AML/CTF measures, with EU bodies having no direct supervisory mandate.5fe75088e32d

In April 2019, the European Council (of member states) rejected a draft list of 23 ‘high-risk third countries’ with weak AML/CTF provisions, which had been drawn up by the European Commission. The list would require higher due diligence standards from European banks interacting with those jurisdictions. According to media reports, controversy arose because Saudi Arabia and several US territories are named on the list.

The Council argued that affected countries were not given enough time to react to the measure, asking the Commission to repeat the process.f3ccb81ec48a Financial transparency as well as taxation thus remain hotly debated issues in Brussels. Time will show if changes are made to further increase transparency, which could help with AR cases.

Second, the EU commands a broad arsenal of economic sanctions as an instrument of foreign policy. This includes the rapid freezing of assets linked to PEPs. These EU misappropriation sanctions are designed to preserve assets so that the affected countries can bring criminal proceedings at a later stage.4709512efffe As the measures in reaction to the Arab Spring have shown, this can (but does not automatically) pave the way for recovery. Reports published by StAR, for instance, decided not to include Libyan assets frozen as part of sanctions, because it was unclear how much of those were related to corruption and would ultimately be repatriated.9b28ce58d18e

The sanctions approach only applies to severe cases in which high-level officials violate human rights, ignore democratic norms, or are linked to terrorism. Kleptocrats might be caught in this net, but it does not apply to quotidian patterns of corruption that fly under the radar of the EU foreign policy. Simply put, European sanctions only targeted Ukraine’s Viktor Yanukovych once the revolution was underway. As one sceptical observer puts it, ‘the mere act of freezing assets is an easy and costless signal of support to revolutions, new authorities, and victims of corruption.’3d35044a1ea6 Sanctions might thus provide a kick-start in some cases but cannot be a substitute for individual efforts to return assets.

Going against the trend?

While momentum in favour of asset recovery and related matters is growing, it seems that some jurisdictions position themselves as alternatives for investors worried about new transparency rules. More countries are following the example set by St Kitts and Nevis in 1984, offering rights in exchange for more-or-less significant investments. About 100 countries around the world – including members of the European Union – now offer individuals the chance to acquire citizenship or residence by investment (CRBI). Media reports cite Malta as one instance in which citizenship is available by means of a non-refundable payment to the government rather than investments in private enterprises or real estate. The United Arab Emirates, to give another example, offer to treat investors as tax residents, collecting no income tax while simultaneously avoiding any exchange of information with other jurisdictions under the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) (Economist 2018a).

The OECD has published a list of 18 CRBI programmes ‘that potentially pose a high risk to the integrity of the CRS’ – including EU member states (OECD 2018b). In January 2019, the European Commission followed suit and issued a report on the CRBI programmes run by Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Malta (European Commission 2019). TI and Global Witness suggest that such schemes were often started or scaled up in the aftermath of the financial crisis. According to their estimate, ‘at least €25 billion in foreign direct investment has flown into the EU through golden visa schemes over the past decade’ (Transparency International and Global Witness 2018, p. 10). CRBI schemes represent a significant source of income for some countries, particularly when they involve fees rather than private-sector investment. Without putting the logic of CRBI under general suspicion, one can assume that it could tempt governments into dragging their feet when it comes to financial transparency.

How can asset recovery serve development goals?

Illicit financial flows and asset recovery have become prominent topics on the global agenda for development. Both are widely promoted by the United Nations: the 2003 UNCAC addresses many aspects of international anti-corruption, with Chapter V containing a pledge and concrete suggestions for asset recovery. In addition, the SDGs include targets to reduce IFFs and to reduce all forms of corruption, lending further urgency to both efforts. Global initiatives, such as FATF and EITI, complement this agenda by mandating international cooperation to curtail money laundering and increase financial transparency. As shown in the previous section, these international efforts have been matched by laws and policies in several key jurisdictions. The United States enjoys unparalleled reach when it comes to all kinds of financial crime; Switzerland and the United Kingdom adopted progressive legislation designed to help with asset recovery. EU initiatives that target money laundering as well as the European ‘misappropriation’ foreign-policy sanctions also provide leverage.

Several aspects of implementation remain fiercely debated (eg UK jurisdictions outside the mainland), or their practical reliability is yet to be proven (eg EU rules for financial transparency or the future use of sanctions). Still, these commitments and rules are significant changes compared to just a few years back. The proliferation of legal rules stands in contrast to the scarcity of data.

Despite many attempts, we lack reliable estimates of the scale of IFFs – and particularly those related to corruption. Likewise, precise information on asset recovery proceedings remain elusive because these activities are decentralised and there is no strong central monitoring (yet). Going forward, those seeking to advance asset recovery with an eye to development goals must address three major challenges.

First, how can IFFs and asset recovery be disentangled to avoid confusion? It is important to define concepts and clarify the intersection between the two, not least to avoid a mismatch of expectations between different actors. Second, how can practitioners and advocates facilitate the transition from public commitments to day-to-day implementation? Implementing asset recovery is challenging, but several recent initiatives have potential to remedy some shortcomings. Third, the agenda to foster asset recovery must be integrated with the broader context of political objectives. Anti-corruption measures, the regulation of transnational markets, financing for development, and other foreign-policy objectives can work in tandem – but they might also lead to conflicting goals. These challenges are discussed in the remainder of this section.

Putting illicit financial flows and asset recovery into perspective

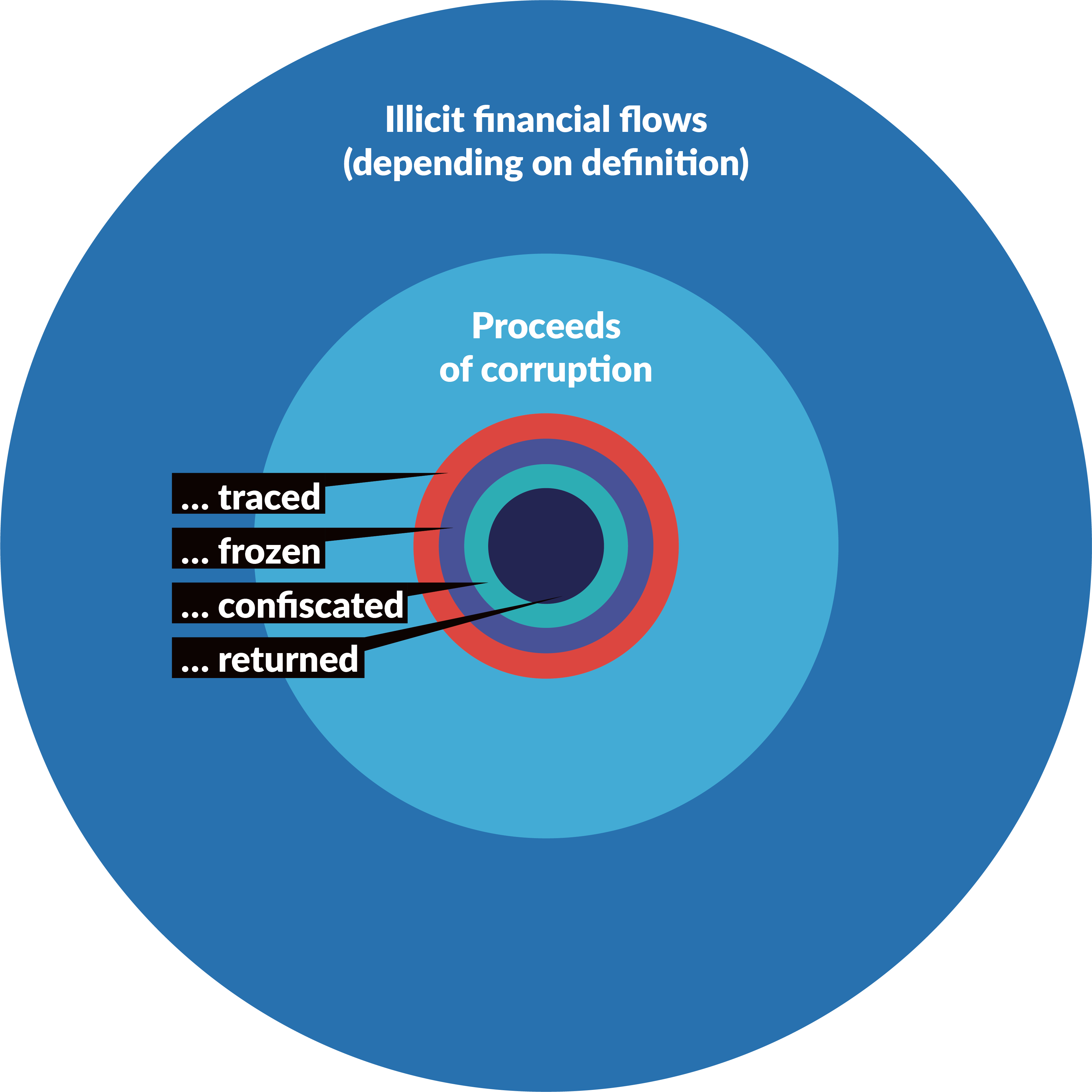

The relationship between IFFs, corruption, and asset recovery can be visualised as a set of concentric circles (Figure 4). Illicit financial flows, as the broadest term, contain various financial transactions of commercial, criminal, and/or corrupt nature. The borders are fuzzy because definitions vary, with some advocates concentrating on clearly illegal behaviour, whereas others propose to include tax avoidance.

Income streams from corrupt practices, as delineated by UNCAC, become a subset of IFFs when they cross national borders. No reliable estimate exists for the share of these funds relative to total IFFs. Some developing countries might experience significant outflows due to high-level corruption but relatively little tax evasion by multinational corporations. In other countries, it will be the other way around. Existing global estimates suggest a share in the single digits for funds stemming from corruption, while publications focused on Africa put more weight on this aspect. Without reliable data to support them, such assessments remain guesswork.7b1b1cd73256

Figure 4: The relation between IFFs, proceeds of corruption, and asset recovery

The inner circles of Figure 4 relate to asset recovery. Presumably, only a fraction of the property hidden abroad by corrupt officials was traced so far. Due to the clandestine nature of corrupt funds, a gap will likely persist. This is not just a matter of loopholes left in regulation for financial transparency. To get the ball rolling, at least one investigative agency needs to pick up a case in the first place, which depends on their incentives and resources. Once ill-gotten funds have been located, the logic of mutual legal assistance requires that requesting states provide evidence to trigger first a freezing and then the confiscation of funds.

In some cases, the financial centre holding the assets might take these steps proactively, for instance as a result of measures against money laundering or as part of international sanctions. The innermost circle of Figure 4, finally, represents the fraction of assets that are returned (repatriated) due to international cooperation and successfully concluded court proceedings.

While we cannot know precisely, the gap between returned assets and the initial size of ill-gotten gains is both large and persistent. Obstacles to implementation (discussed in the next section) are to blame, and recent political developments suggest potential to narrow the gap. At the same time, however, the involved parties ought to acknowledge that estimates of illicit financial flows do not automatically translate into expected returns of equal size. When IFFs are defined in a way that goes way beyond flows related to corruption, UNCAC only applies to that fraction of the total: Chapter V, which deals with asset recovery, refers to ‘property acquired through the commission of an offence established in accordance with this Convention.’bb7fc6688a27

Moreover, the preventive measures in Chapter V pertain to due diligence regarding, among others, PEPs. This illustrates the focus of UNCAC’s provisions on corruption, with emphasis on public officials. Different rules apply for other proceeds of crime, eg Article 5 of the UN Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances and Article. 14 of the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC). Profit-shifting and tax fraud, in contrast, are covered by neither UNCAC nor UNTOC.

Thus, while activists such as the Tax Justice Network make persuasive arguments for global reforms when it comes to taxation,c731b98b7bf5 their perspective on IFFs cannot be equated with the narrower category of criminal proceeds defined in UNCAC and UNTOC. As noted earlier, the scope of the IFF concept is hotly debated.

Having IFFs as an umbrella term may be beneficial for activists but raises problems of measurement and of practical implementation. A pragmatic compromise might combine disaggregated measurements with working definitions tailored to specific actors.0221079898c9 Goals and expectations must then be linked to empirical estimates for the respective (sub-)elements of illicit financial flows. This is crucial for at least three reasons.

First, contrasting the scale of IFFs to the size of external debt and development assistance can help to add weight to political demands. However, this line of reasoning does not easily translate into legal arguments for repatriation in accordance with UNCAC. Developing countries rightly emphasise the shared responsibility for asset recovery.828f1890af53 Yet the catch-all approach to IFFs risks leading to mutual disappointment: developing countries may find the returns from legal assistance in corruption cases surprisingly small compared to the enormous sums circulating in parts of the literature. Financial centres, meanwhile, may be frustrated by seemingly excessive demands paired with limited progress on individual cases.

To avoid confusion and mutual disappointment, one should clearly differentiate between global financial flows (including the separate debates about taxation, debt relief, and sustainable development) and the issue of asset recovery. For IFFs, detection and prevention must be improved both at the source and at the destination. For AR, many proposals exist for cooperation to streamline procedures and become more effective (see the next section).

Second, and closely related to the first point, the notion of IFFs is problematic when it comes to measurement. Realising the mandate and the measurement requirements enshrined in the SDGs will be challenging: ‘This expanded agenda, and the often tenuous links between combating IFFs and larger global goals, has made measurement of the effectiveness of international action – problematic for all global governance and international institutions – even more difficult for the actions taken to counter IFFs.’fd1d9242c83d It may take years until a consensus measure is found to assess progress on SDG 16.4.3c40de695975

As the literature shows, the definition of IFFs is contested. Many proposals exist to promote the broader agenda.69c9ae155eb3 That is why anti-corruption and development actors need to clarify which parts of the IFF agenda they find most relevant, and how different aspects relate to each other.

Third, measures to curb transnational flows do not directly address the underlying corruption rooted in domestic politics and institutions. Still, tackling IFFs might bring benefits even if corrupt practices persist. All else being equal, ill-gotten gains might be invested closer to the source if it becomes more difficult to move them across borders, thus contributing to private-sector investment and taxation in developing countries. Optimists argue that measures to curb IFFs can even change the incentives for political elites.

If the proceeds of corruption cannot be translated into a lavish lifestyle overseas, and if misappropriated funds are confiscated as soon as political power shifts, kleptocracy might become less attractive for rulers. Yet pessimists fear that kleptocrats may become even more ruthless under such circumstances. Ultimately, corruption will likely remain tempting for officials who face few constraints at home.d675d9f573ff International initiatives related to IFFs and AR can thus make an important contribution but are no cure-all.

Implementing asset recovery: Challenges and chances

The creation of inter-agency teams for dealing with foreign kleptocrats, as in the UK and Switzerland, is an important first step to ensure that such cases receive the necessary attention. From that starting point, how can success regarding asset recovery be measured? Ideally, a modest amount of resources spent on investigations and prosecutions would lead to significant asset seizures and repatriations, which would in turn have positive effects on development while deterring leaders from corruption. A recent estimate of the cost-effectiveness of AR concludes that such an ideal outcome seems out of reach for now.7b0e71ef2ca8 Yet there are ways to improve the practical implementation of asset recovery, suggesting incremental steps towards success.

What are the main challenges that need to be addressed? From the perspective of OECD states, a major part of the impediments to asset recovery seems to be of a technical and legal nature.0982eecea996 Simply put, recovery efforts can be frustrated when ‘victim’ states do not produce formal requests for legal assistance or accompanying evidence in line with the requirements of the respective legal system in the requested state.

UNCAC is not a recovery mechanism in itself; it relies on successful intergovernmental cooperation.4672ddf08cd5 At the same time, however, the challenging nature of AR proceedings is acknowledged in Article 60(1), which directly follows UNCAC Chapter V with suggestions for training and technical assistance. Initiatives like StAR, ICAR, and the Lausanne Seminars are crucial for capacity building and the exchange of best practices. Additionally, development agencies – particularly from financial centres – are in an ideal position when it comes to the technical and legal side of AR: with roots in the requesting and requested states, they can build expertise and create awareness on both sides.26bbe26d2190

Several documents offer concrete guidelines (see Table 2): the G20 endorsed ‘Nine Key Principles of Effective Asset Recovery’ in 2011;a67d58ba945e the 2014 Lausanne ‘Guidelines for the Efficient Recovery of Stolen Assets’ have been updated with a step-by-step guide and posted online;89b23d25fba6 the 2017 Global Forum for Asset Recovery adopted ‘Principles for Disposition and Transfer of Confiscated Stolen Assets in Corruption Cases;’760fd2394080 and most recently, the 2018 and 2019 UNCAC IRG meetings discussed guidelines on the management of frozen, seized, and confiscated assets.7c519046913f

Table 2: Guidelines for asset recovery according to four recent documents

|

G20 (2011) Nine Key Principles of Effective Asset Recovery |

Lausanne (2014) Guidelines for the Efficient Recovery of Stolen Assets |

Global Forum (2017) Principles for Disposition and Transfer of Stolen Assets in Corruption Cases |

UNCAC IRG (2018–19) Guidelines on the Management of Frozen, Seized, and Confiscated Assets (selection) |

|

|

|

|

Even in cases where the scope of assets to be confiscated is clear and first steps proceed quickly, the act of repatriation can be contentious. Requested states might be reluctant to release assets if they fear the requesting-state government is unable to ensure their proper handling for the public good. In the worst-case scenario, funds could again be misappropriated by corrupt actors. More generally, they could be repatriated without any positive effect on the well-being of the population. Facing those considerations, requested states may insist on monitoring or other measures to ensure assets are being used in the spirit of UNCAC.5bd9da292bc1

Another challenge concerns the assets of sitting government officials. Several jurisdictions have adopted, or are currently introducing, stringent regulations on money laundering and more progressive laws on foreign PEPs. As a result, they are more likely to discover funds associated with seemingly corrupt behaviour by actors currently holding office. While such forms of AR are in line with the intentions of UNCAC, they raise questions about how to proceed, because those cases are not based on a request for mutual legal assistance.

Legal and development experts are exploring ways to address these concerns. Swiss and British agencies, for instance, channelled repatriated funds into development projects in Angola and Tanzania, respectively. Another well-known example is the Kazakh charitable foundation created in accordance with a US–Swiss settlement.d7132dd003bf In France and the United States, assets belonging to the Obiang family (still in power in Equatorial Guinea) were seized, with the money from the US settlement going to charity while the French case is ongoing.515146d9c709

Making sure that the final stages of asset recovery proceed in line with development goals is an important task for practitioners and activists. Yet the notion of controlled and/or contingent repatriation is political rather than a mere technicality. African governments have expressed their concerns. The UNECA report on IFFs emphasises the importance of close cooperation but also makes it clear that AU member states strive for asset recovery with no strings attached:

‘We believe that frozen assets should not be kept in banks that are complicit in receiving these assets. Rather, they should be kept in an escrow account in regional development banks, which in the case of Africa is the African Development Bank. In addition, countries where illicit financial outflows have been secreted should not have the prerogative of stipulating the conditions for their return.’6b9701a70a0a

This ties in with the broader criticism of industrialised countries for their alleged complicity in transnational corruption.2f6e896afb0e Yet mechanisms to regulate and monitor the disposal of recovered assets have their place to ensure that development goals take centre stage. The Obiang case, for instance, shows that the picture is often quite complicated, and that allocating assets to third parties such as non-governmental charities might be the best way to act in accordance with both anti-corruption and development goals. Nonetheless, the examples show that the political nature of repatriation requires that both developing countries and OECD members communicate clearly and consider each other’s expectations. Otherwise, there is a significant risk of mutual disappointment.

Another trend concerns the fact that civil actions are increasingly being chosen to avoid burdensome criminal proceedings. Seeking remedies from corrupt officials in civil courts usually means that standards of evidence are not as demanding (balance of probability). Moreover, assets can be seized to pay for damages even if they cannot be directly linked to corrupt acts and thus not criminally confiscated.29f7b020a9d4 Together with non-conviction-based forfeiture, such approaches thus provide viable alternatives if criminal proceedings seem challenging. Recent examples include civil actions brought by Angola against allegedly fraudulent management of its sovereign wealth fund and actions taken by Mozambique against Credit Suisse and others.18a6b6e93672

One thing is clear: proponents of asset recovery must identify what works and what does not. All parties to UNCAC, members of the OECD, and supporters of StAR should strive to make asset recovery more transparent. This means collecting systematic data and publishing fine-grained information for as many countries as possible. UNCAC’s peer review collects information on asset recovery and encompasses the widest possible range of countries; this potential should be used.

In the meantime, the OECD peer review is the most promising venue to create a precedent for transparency. OECD member states, after all, are home to key financial markets and have experience with monitoring in other policy areas. The organisation’s reporting mechanisms on foreign bribery and AML/CTF measures could be used as an example.73fb23920f60 In the long run, however, the full picture can only be achieved if non-OECD countries also provide data on investigations and cooperation, the types and sums of assets involved, and the status of proceedings. By expanding the StAR database or using a new format tied to the UNCAC peer review, this information should be made accessible to all interested parties. Such transparency would energise the AR agenda by identifying gaps as well as role models.

Aligning political objectives