Query

Please provide examples of integrating human rights and anti-corruption in development projects.

Caveat

There is limited information in the public domain on specific development projects that have intentionally and successfully integrated measures intended to promote anti-corruption and human rights. This paper seeks to provide illustrative ways in which these components can be brought into alignment throughout a project cycle. A few examples of projects have also been included. These range from anti-corruption programmes that have adopted a human rights perspective to human rights initiatives that include an anti-corruption element, as well as other types of thematic development programmes that incorporate both anti-corruption and human rights considerations.

Background

Both anti-corruption and human rights are enshrined as important components in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which enshrines them as necessary conditions needed to achieve each and every one of the 17 goals.

Human rights, for example, are central to the 2030 Agenda’s pledge to leave no one behind in social, environmental and economic development. There is explicit recognition of the need for those charged with implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to “realise the human rights of all.” Indeed, the 2030 Agenda is deeply rooted in human rights principles and standards, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and international human rights treaties (OHCHR 2022b). For instance, SDG 5 addresses gender equality, SDG 10 addresses inequities within and between nations, while a cross-cutting commitment to data disaggregation underscores the 2030 Agenda’s dedication to the values of equality and non-discrimination (OHCHR 2022b).

Anti-corruption, on the other hand, is included in various targets (reducing bribery, strengthening institutions and accessing information) under SDG 16, which relates to the promotion of just, peaceful and inclusive societies (UNDP 2020; United Nations 2022).

National governments are not the only actors with a mandate to advance sustainable development through measures to curb corruption and promote human rights. Development agencies have a significant supporting role in SDG implementation, and numerous development frameworks and aid effectiveness principles34efe4cb3b9a emphasise how these actors are expected to promote “human rights, democracy and good governance” as “an integral part of [their] development efforts” (OECD 2011).

Corruption and human rights abuses are two distinct phenomena. However, the links between them are clear. Kukutschka and Vrushi (2022) note that:

- The presence of corruption can weaken a government’s ability to fulfil its human rights obligations by undermining the overall functioning of the state – from the delivery of public services to the dispensation of justice and the provision of safety for everyone (ICHRP 2009)

- Corruption in law enforcement can jeopardise people’s safety and victims’ access to justice, while private actors can rely on bribery and/or personal connections to ensure that the state turns a blind eye to human rights abuses (Mijatović 2021)

- Corruption and impunity contribute to an unsafe climate for human rights defenders to operate in (Frontline Defenders 2020)

In this respect, before turning to specific examples of programming that target the interplay between corruption and human rights violations, it is helpful to tease out some of the conceptual links between corruption and human rights.

The paper then considers examples of where development agencies have sought to embed anti-corruption and human rights into their programmes to safeguard their funds from misuse and uphold the interests of rightsholders in line with the “Do No Harm” principle.

Understanding interlinkages between corruption and human rights

Corruption is widely acknowledged to threaten not only a variety of human rights but also the rule of law and democratic norms. For instance, the right to a fair trial and remedy can be restricted by judicial corruption, which can also foster related violations such as “extrajudicial imprisonment and torture” (Zamfir 2021).

On the other hand, the use of public resources to advance socio-economic rights (such as the right to an adequate standard of living, a basic level of education, and access to health care) is hindered by corruption, which thus acts as a significant barrier to sustainable development (Zamfir 2021).

Corruption is known to undermine governance quality and public trust by “weakening state institutions that are the basis for fair and equitable societies with access to justice for all” (UNODC 2018). Good governance and human rights tend to be mutually reinforcing. Human rights principles can be used to inform the development of good governance initiatives, budget allocations and reform to legislation, policies, programmes, while the rule of law is necessary to defend human rights in a sustainable manner (OHCHR 2022a).

It is worth noting that corruption can undermine the “right to non-discrimination”ce0ada0edf26 (Zamfir 2021). Corruption and its intertwined relationship with discrimination has a particularly negative impact on the human rights of the poor and marginalised (Zamfir 2021; McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021: 11). Anti-corruption, therefore, in the form of “accountability, transparency and participation measures” buttresses both good governance and the enjoyment of human rights (OHCHR 2022a; UNSSC 2022).

Conversely, respect for human rights in anti-corruption campaigns is a necessary factor to ensure that crackdowns on corruption do not turn into a means to suppress opposition. In China, for example, Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign between 2012–2017 “transformed into an exercise of power-consolidation for his office” (Li 2018; Tiezzi 2014). Similarly, in Saudi Arabia between 2017 and 2019, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman ordered an anti-corruption purge targeting high-level officials and members of the royal family, in what critics coined a “power grab” (Kirkpatrick 2019). In another case of prosecuting corruption, the UN Human Rights Committee found that the investigation and trial of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the former president of Brazil, was found to have been in violation of his right to an impartial tribunal, his political rights and his right to privacy (OHCHR 2022c).

Recent analysis of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2021 demonstrates a clear correlation between countries with good human rights records and those that are perceived to control public sector corruption effectively. Conversely, countries in which human rights violations are egregious and widespread perform poorly on international indices of corruption control. Indeed, “very few countries have managed to establish control of corruption without also respecting human rights”, and this relationship holds even when controlling for a country’s level of economic development (Kukutschka and Vrushi 2022). Analysis by Kukutschka and Vrushi (2022) suggests that beyond mere correlation, corruption can provide impunity for human rights abuses and contribute to democratic decline, which in turn, reduces the constraints on corruption. Such findings suggest that “protecting human rights is crucial in the fight against corruption” (Transparency International 2022).

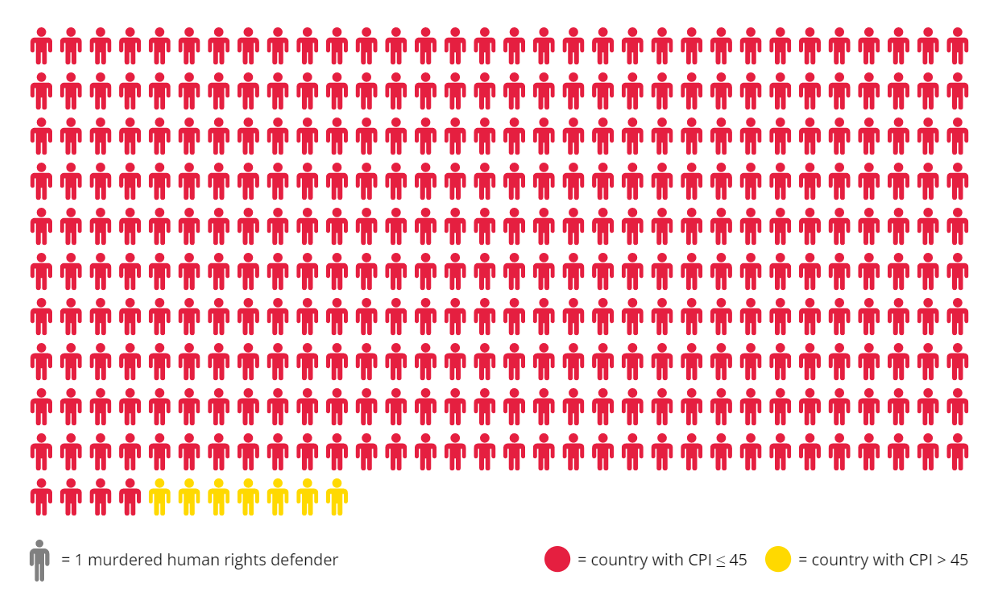

Corruption creates a dangerous environment for human rights defenders, whistleblowers and investigative journalists (Human Rights Council 2021; Council of Europe 2021). According to an analysis of the data gathered by Frontline Defenders, in 2020, 98% of the 331 murders of human rights advocates around the world occurred in countries with high levels of perceived corruption (a CPI score below 45). In addition, at least 20 of the killings involved the deaths of human rights defenders who were working to counter corruption (Vrushi and Kukutschka 2022).

Figure 1: infographic depicting corruption and murdered human rights defenders

Source: Frontline Defenders (2020) and Vrushi and Kukutschka (2022)

Other human rights defenders particularly at risk of attack include (Norwegian MFA 2010: 17):

- women who fight for human rights

- advocates for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people

- defenders of human rights in rural areas as they frequently require more protection because they tend to be less visible

- people or organisations involved in disputes involving significant financial/economic interests: these could include those conducting major corruption investigations

- environmental activists and rights defenders

- those fighting for the rights of Indigenous and minority people

A report by the special rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders lists the types of risks and structural challenges faced by human rights defenders working against corruption, as well as suggestions for how relevant stakeholders may protect and support their work (OHCHR 2021).

While respect for human rights is clearly not the only driver of a state’s ability to control corruption, it does provide the normative framework and support to the rule of law that is conducive to sustained progress in reducing levels of corruption over time.

Anti-corruption efforts must consider the possibility that they could also undermine human rights (Human Rights Council 2015). In contexts where human rights violations are common, anti-corruption prosecutions that may not adhere to human rights standards can violate people’s right to privacy, due process and a fair trial (Merkle 2018: 5).

As Marquette (2021: 10) suggests, one of the main goals in this area is reducing impunity, which starts with “having more honest conversations about the ways in which fighting corruption may not work and may even weaken democracy.” In this view “do[ing] anti-corruption democratically” also involves tackling global networks that facilitate corruption and erode democracy while simultaneously strengthening democratic oversight and accountability mechanisms at the national level (Marquette 2021: 10).

Mainstreaming anti-corruption and human rights in development programming

Various development agencies have sought to mainstream either anti-corruption or human rights in their work in several ways. For instance, through the new Strategy 2030, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) is “calling [on their] partner countries more than before to provide evidence of progress made on good governance, human rights and fighting corruption” (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development 2020). Human rights have been a binding principle of German Development Cooperation since 2011. The new BMZ reform strategy, BMZ 2030, establishes six quality criteria, among them one for “human rights, gender equality and inclusion” and another one for “anti-corruption and integrity”. The criteria are a seal of quality of German development cooperation that need to be considered in all intervention measures and at all levels. Their application is mandatory for BMZ and its implementing agencies (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development 2020).

As well as requiring partner countries to demonstrate commitment to human rights and anti-corruption, the strategy obliges all German programmes in the area of development cooperation to demonstrate that they contribute to promoting human rights and curbing corruption. In response, the GIZ Sector Programme on Human Rights has sought to ensure that all of its development activities are aligned with human rights standards and principles. The two-pronged approach involves supporting state actors in fulfilling their human rights obligations and assisting rightsholders, especially the structurally marginalised and discriminated, to claim their rights. This involves an examination of gender norms, discrimination and power imbalances that stand in the way of achieving full equality for all.

On the other hand, the BMZ Tackling Corruption and Promoting Integrity project seeks to “mainstream anti-corruption and integrity in development cooperation more effectively” in its work (GIZ 2022b). It does so through:

- ACWalk: provides anti-corruption guidelines, tools and potential strategies

- ACPolitics: promotes anti-corruption in the development agenda

- ACLabs: creates innovative methods

However, when it comes to the topic of howto harmoniously integrate both anti-corruption and human rights considerations into a given development project, there is limited information or guidance in the public domain.

This answer thus seeks to list illustrative ways in which human rights and anti-corruption can be integrated in a complementary manner through a development project’s life cycle. Then, in the final section, the paper presents a few project examples grouped into the following categories:

- anti-corruption programmes that include elements of human rights

- human rights projects that include anti-corruption components

- other projects that include elements of both while being focused on neither

When considering development programming in the context of human rights and anti-corruption, it might be worth considering that projects could lead to human rights violations and feeding corruption. Aid may operate as a type of “resource curse” because it allows elites to avoid investing in public goods and using funds for their enrichment. Aid projects can also potentially lead to human rights breaches, especially when they involve relocating vulnerable groups or supporting a partner state’s law enforcement. In various countries, USAID financing channelled through WWF led to human rights abuses. These incidents have prompted the US to try to pass new legislation to safeguard international development and conservation “beneficiaries” (Natural Resources Committee 2021). Overall, positive outcomes from development aid initiatives should not be assumed; and risk analysis ought to be conducted case-by-case.

Integrating anti-corruption and human rights through the project life cycle

Anti-corruption

There are two main dimensions of integrating anti-corruption efforts into development cooperation that aid agencies must consider. Development agencies ought to implement internal safeguards to protect their own finances from corruption; these can include codes of conduct, internal controls and audit functions, anti-corruption clauses in contracts, whistleblowing mechanisms and personnel rotation, among others. Development agencies can also seek to improve partner countries’ anti-corruption capabilities through targeted support (Boehm 2014: 1).

On the internal corruption risk management front, development agencies ought to identify, assess, treat and consequently monitor corruption risks within their projects (Jenkins 2016: 2-3). Johnsøn (2015) provides a detailed model of corruption risk management here.

Simply identifying corruption risks is not enough. Tolerable levels of risk need to be determined after identifying potential threats to the project’s outcomes or the donor’s reputation or fiduciary interests. It is critical to define the project’s “risk appetite” before work can begin as risks that exceed predetermined levels would necessitate more stringent preventative or corrective actions.

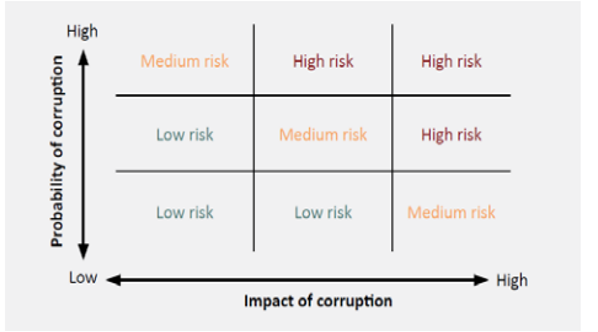

Second, it is necessary to undertake a risk assessment to weigh the magnitude of the potential threats. One way to do this is by multiplying the likelihood of an event occurring by the magnitude of its possible impact in a risk matrix to get at an estimate of the degree of risk involved. Project managers can use this technique to prioritise their efforts to mitigate corruption risks when the project is being put into motion (Jenkins 2016: 2).

Figure 2: Basic risk matrix

Source: Johnsøn (2015)

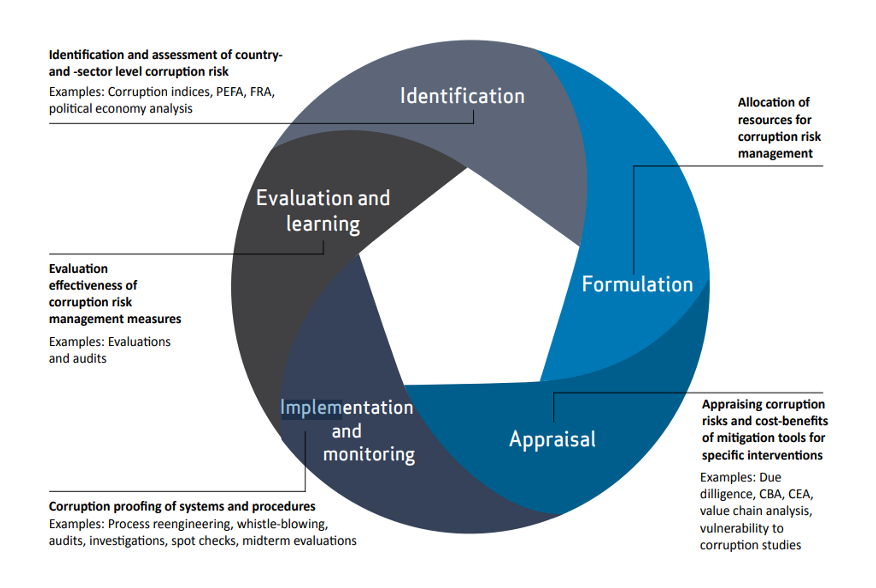

Corruption risk management across the project cycle

Inception stage: middle management at a development agency is typically tasked with identifying and assessing “higher order” corruption issues to define the organisation’s risk appetite (Jenkins 2016: 4).

Planning phase: project teams do a comprehensive risk analysis, develop preventive tactics and mitigation plans, and establish who is responsible for which areas in risk management (Jenkins 2016: 4).

Implementation phase: corruption risks peak during this phase, when money can be embezzled or misappropriated through fraudulent procurement practices. Moreover, assets can be exposed to the risk of being mismanaged, and bribery and facilitation payments for local approvals, licences and access can be a challenge (Jenkins 2016: 4, 6-10).

Closing phase: while corruption tends be lower at this stage, risks persist in delivering goods or services to local populations, signing off on expenses or audit trails (Jenkins 2016: 4).

Monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL): throughout the life cycle of a project, monitoring is needed to keep an eye on new risks. Evaluations can reveal project successes and failures. However, conventional MEL (typically “project-focused, ex-post, and designed and delivered by external foreign evaluation teams”) may not always fulfil local settings’ demands (Coger et al. 2021, 10; Rahman 2021: 9). Thus, MEL frameworks should recognise structural disparities, integrate local communities while maintaining gender balance, and enable value-creating MEL activities (Rahman 2021: 9-10).

Johnsøn (2015) depicts the various tools that can be used in mitigating corruption risks through the project life cycle in the following infographic:

Figure 3: Corruption risk management across the project cycle

Source: Johnsøn (2015: 15).

When dealing with corruption externally, development agencies can investigate and evaluate sector-specific corruption issues, and devise solutions to address them in order to enhance the sector’s performance. Development agencies can assist partner governments establish and execute sectoral anti-corruption policies to promote sector governance and service delivery by supporting such programmes. Development agencies can also help partner institutions, such as ministries (even human rights bodies), develop their internal anti-corruption capacities (Boehm 2014: 1).

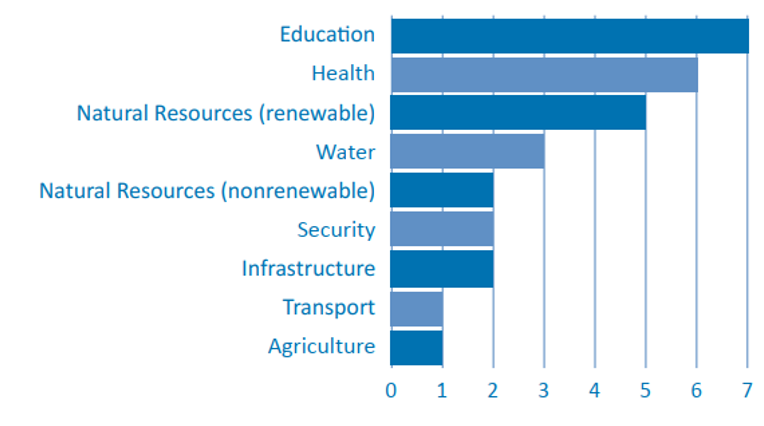

On the subject, U4’s exploratory survey of its partner development agencies’ experience of mainstreaming anti-corruption into sectors found that corruption is viewed as a cross-cutting issue by all. In fact, six of the seven were known to have a strategy in place that clearly required anti-corruption concepts to be mainstreamed into sector programmes (Boehm 2014: 3). A few sectors in which development agencies have integrated an anti-corruption approach are displayed in the following infographic:

Figure 4: sectors in which U4 partner agencies have experience in integrating an anti-corruption

Source: Boehm (2014: 3)

A crucial point to note in integrating an anti-corruption perspective into any development programme is that must it be customised to the project and context of the intervention at hand. Copy-pasting solutions from context A to context B without an understanding of the peculiarities of a specific operational scenario can prove counterproductive.

Human rights

A central theme in mainstreaming human rights in development programming is applying a human rights based approach (HRBA). HRBA is defined as a “conceptual framework for the process of human development that is normatively based on international human rights standards and operationally directed to promoting and protecting human rights” (UNSDG 2022). This method seeks to “analyse inequalities which lie at the heart of development problems” and overcome discrimination and imbalances in power that stymie development efforts which often result in “groups of people being left behind” (UNSDG 2022).

In practice, applying a human rights based approach to development programming requires some core considerations (HRBA Portal 2022):

- human rights principles such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and other international human rights instruments/bodies ought to influence programme design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation

- assessment and analysis to identify rights-holder claims, duty-bearer responsibilities, and immediate, underlying and structural causes of non-realisation of human rights (such as corruption)

- programmes ought to examine rights holders’ ability to assert their rights and duty bearers’ ability to execute their duties, and then work towards building these capacities

Additional features of good programming practices that are unique to a human rights-based approach include (HRBA Portal 2022):

- people are seen as a driving force behind progress, rather than a mere recipient of goods and services

- participation is both a means and an end

- strategies ought to be empowering

- the processes as well as the outcomes are monitored and evaluated

- everyone who has a stake in the outcome is accounted for in the programme analysis

- special attention is paid to those who are at risk of discrimination

- locally owned and led development actions

- countering inequity is the target of these initiatives

- there is a complementary use of top-down and bottom-up strategies

- situation analysis identifies development challenges’ immediate, underlying, and fundamental causes (including corruption)

- programmes need to include objectives that can be measured for success

- the formation and maintenance of strategic partnerships

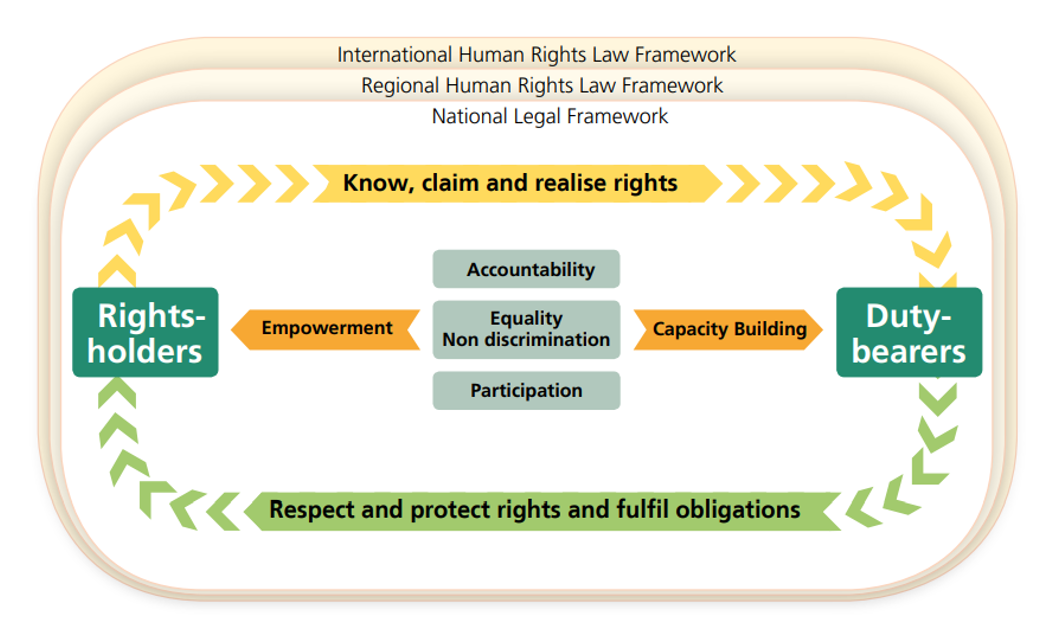

The following infographic represents the core dimensions of a human rights-based approach:

Figure 5: The core dimensions of the human rights-based approach

Source: SDC (2019: 8)

Embedding a human rights-based approach through a project cycle includes the following considerations.

Assessment and analysis: at this level, the goal is to identify rights-holders and the related human rights responsibilities of duty-bearers, as well as the immediate, underlying and systemic causes of rights’ non-realisation, for instance, corruption (Merkle 2018: 13).

Planning and design: the recommendations of international human rights agencies and instruments ought to be taken into consideration while developing programmes (Merkle 2018: 14-15). UNICEF Finland, for example, identifies seven steps for human rights-based programme planning (Hausen and Launiala 2015: 21-28):

- Situation analysis: the first step in designing a project is to have a better understanding of the specific problem that the project aims to solve from a human rights standpoint, as well as the reasons that underlie those goals.

- Causality analysis: assists in identifying varied reasons of non-fulfilment of a single human right in a specific scenario, as well as a list of potential rights holders and duty bearers.

- Role pattern analysis: it determines or verifies the specific people or groups of people who have claims about the issue, its causes and unfulfilled rights.

- Capacity gap analysis: it examines the barriers that the people who have rights face to asserting their rights, as well as the gaps in capability that duty-bearers face to fulfil their obligations. It examines a variety of aspects, such as the accountability, authority, resources, decision-making and communication capacities of those who possess rights and bear responsibilities.

- Identification of candidate strategies and action: outlines measures that may help bridge rights-holder and duty-bearer capacity gaps.

- Partnership analysis: identifies the main players in the area of intervention who are dealing with the same challenges and examines their strengths and expertise.

- Project design: actions that are identified as high priority then need to be grouped together into a single project with well-defined goals, milestones and outcomes.

All of these steps need to involve both rights-holders and duty-bearers. For human rights mainstreaming to be successful, a human rights-based approach needs to be used throughout the planning and design process (Merkle 2018: 15).

Implementation: an essential focus of this phase is on empowering rights-holders and strengthening the obligations of the duty-bearers to protect and guarantee those rights. Moreover, the implementation phase needs to focus on the meaningful participation of all affected by the programme (Merkle 2018: 15).

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E): programmes should monitor and evaluate outcomes and processes guided by human rights standards and principles (Merkle 2018: 15). Human rights-based M&E requires that benchmarks and indicators reflect HRBA principles (for example, measuring the quality of the “process” as well as the “results”), and that it strives to be empowering and participatory, for example, by including rights-holders in the selection of benchmarks/indicators, the drafting of evaluation terms of reference, and participation on evaluation steering committees. Human rights-based M&E processes are non-discriminatory, gender-sensitive and measure those characteristics that are crucial to outcomes (SDC 2022: 8).

Throughout the project cycle, applying a human rights-based approach entails focusing on the “Do No Harm” principle, which includes “consideration of positive/negative human rights results from different intervention options (methods, programme partners etc)” (SDC 2022: 2). Clear, effective and conflict-sensitive communication on human rights in programming is also “essential to empowering rights-holders, thereby delivering optimum, sustainable development results” (FCHR 2021). More details on making such communication possible is available here.

Combining anti-corruption and human rights approaches in development programming

There is limited information on how human rights and anti-corruption can be integrated in development programming. From an anti-corruption perspective, however, it has been acknowledged that by tackling corruption through a human rights framework “the social impact of corruption is made visible; this generates awareness in society about the consequences of this scourge and creates new alliances in the fight against corruption” (UNHRC 2015: 10).

In curbing corruption, the human rights-based approach and the criminal justice approach000dcc15f8df complement each other because they highlight different harms and responsibilities (UNODC 2021: 26). The criminal justice approach posits that acts of corruption perpetrated by individuals, such as a government official who accepted a bribe or embezzled public funds, have harmed the state (and the citizens it represents). The human rights-based approach focuses on how the state has violated its duty to the public by failing to protect it from corruption, as well as the necessity for the state to provide remedies (UNODC 2021: 26). Some scholars argue that “the right to a corruption-free society is, or should be, a free-standing human right” (UNODC 2021: 28).

There are several advantages of applying a human rights-based approach to corruption:

- It is victim focused and works to empower those marginalised people who are most at risk of suffering the consequences of corruption. Simultaneously the approach seeks to “transform them into actors in the fight against this problem” (UNODC 2021: 26).

- Increases transparency and participation, which in turn boosts the likelihood of corruption being detected and human rights being addressed, promoted and protected (UNODC 2021: 27).

- Accountability is strengthened through wider participation and transparency measures, which empowers citizens to better monitor those holding power. Moreover, mechanisms that are a part of human rights treaty bodies (such as grievance and complaints procedures) can be leveraged by individual victims of corruption for seeking redressal (UNODC 2021: 27).

- Bringing corruption claims and cases before international and regional human rights adjudicators and monitoring mechanisms could assist victims with remedies (UNODC 2021: 27). Even international human rights mechanisms can act as powerful tools to address corruption on the respective state level in its reports.

- Considering corruption as a human rights violation could supplement existing anti-corruption efforts by allowing human rights tribunals, commissions and constitutional courts to examine cases involving people’s rights violated by corrupt activities. This increases the number of actors working in the area. However, a caveat here would include being mindful of the duplication of similar activities between anti-corruption and human rights bodies (UNODC 2021: 27-28).

In delineating the nexus between corruption and human rights in a given context, it is imperative that the casual relationship between the two is effectively established (i.e., not all acts of corruption would violate human rights). Rose-Sender and Goodwin (2010: 1–3) opine that efforts at linking the two discourses have been “either so straightforward as to be prosaic or else incoherent when taken as suggesting a more profound connection”. They add that these efforts are also part of a trend in development and international law to incorporate human rights into separate components that evolved in parallel (such as anti-corruption) (UNODC 2021: 28).

For greater detail on mainstreaming human rights in anti-corruption programming please refer to the paper here.

Illustrative project examples

Examples of programmes that are focused on anti-corruption and include elements of human rights

Using an ‘Equality by Design’ approach in the Rallying Efforts to Accelerate Progress (REAP) – Africa Inequalities Initiative

The ongoing REAP project is currently being implemented by Transparency International Secretariat, Transparency International Kenya (TI Kenya) and Corruption Watch (TI South Africa) (Transparency International 2021). The main aims of the project include:

- greater social accountability over policies and decisions that fuel and sustain income and wealth inequalities

- better access to public resources for vulnerable and marginalised groups in Kenya and South Africa

- stronger regional and global action to disrupt the mechanisms that enable illicit financial flows (IFFs), tax evasion and tax avoidance, undermining African countries’ sustainable development

To ensure that the “leave no one behind” principle is being respected, and anti-discrimination, as an important human right is included in the project, REAP is applying an “equality by design” framework developed by the Equal Rights Trust (ERT 2022). The equality by design framework involves subjecting all project activities to three questions (ERT 2022):

Who is involved?

The initiative adopts an “intentional, inclusive and intersectional” method to identify marginalised groups who can be both positively and negatively affected by the project. The next step involves engaging with these groups while being mindful of barriers to their participation to develop a “safe and sensitive, appropriate and accessible” approach. Lastly, ensuring that there is meaningful involvement of affected groups in the design, delivery and monitoring of the project and its activities (ERT 2022).

How is the activity implemented?

To make the project truly equality sensitive, staff are trained on the international standards on equality law to enable them to “understand and identify forms and patterns of discrimination” in the outcomes the project wants to achieve as well as in terms of its delivery. “Pre-emptory, participatory and data-led” equality impact assessments involve consultations with identified stakeholder groups to understand both positive and negative impacts of intended activities. Project monitoring and evaluation has a criterion to include an appraisal of outcomes and impacts for all groups exposed to discrimination (ERT 2022).

What does the project seek to achieve?

Through stakeholder involvement and equality impact assessment, decision makers should determine if and how project outcomes reduce inequality. All parts of a project should be considered, but especially focusing on capacity-building, research and advocacy actions can be useful (ERT 2022).

Indonesia: Involving key institutions in anti-corruption reform

Diani Sadiawati, a planning agency official in Indonesia, was given the task of developing the government’s anti-corruption strategy in 2010, with a focus on preventive policies (Dreisbach 2017: 1). The reform group opted to focus on the 16 most prominent ministries and institutions that operated in the areas most vulnerable to corruption, such as the legal system, the public sector, the health and education sectors (Dreisbach 2017: 6). Specific agencies involved included the police, the attorney general’s office, the Ministry of Law and Human Rights and the Ministry of Finance (Dreisbach 2017: 7).

One overarching aim of the reform group was to develop, refine and promote ethics codes and integrity norms within institutions. For instance, the team negotiated with the Ministry of Law and Human Rights on how to enhance the human rights of prisoners by reducing corruption in the penal system, and established measures to better monitor ethical violations, strengthen accountability mechanisms for offenders and develop a specialised code of ethics for prison officials (Dreisbach 2017: 7).

The Ministry of Law and Human Rights contributed to success in other fields as well. For example, the Ministry of Law and Human Rights engaged in redesigning a passport procedure that was known to be highly corrupt. Their re-designed process eventually resulted in reduced wait times and eliminated cash payments (Dreisbach 2017: 14). In terms of overall achievement of the reform strategy, by 2015, 88% of commitments had been fulfilled (Dreisbach 2017: 14).

However, it ought to be noted that the conditions for both anti-corruption and human rights at the national and subnational context in Indonesia has been deteriorating in recent years (HRW 2022; TI Indonesia). There have also been “numerous reports of unknown actors using digital harassment and intimidation against human rights activists and academics who criticized government officials, discussed government corruption” (US Department of State 2021: 2).

Countering corruption in South Africa

The Transparency, Integrity and Accountability Programme (TIP) in South Africa commissioned by BMZ and co-funded by the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) supports the country’s national anti-corruption strategy (GIZ 2022c). A key area of the strategy is to “support and protect human rights defenders that are champions of transparency, accountability and anti-corruption activities” (Republic of South Africa 2020: 44-45).

The project takes a “whole-of-society approach” to involve state, private entities and civil society actors in the strategy’s implementation (GIZ 2022c). The project aims to support anti-corruption bodies, promote integrity in the management of businesses and foster multi-stakeholder partnerships. This is achieved through three main outcomes (GIZ 2022c):

- The first area fosters citizen engagement by encouraging openness, integrity and accountability.

- The second area attempts to increase institutional resilience so that state actors can direct strategy implementation and coordinate activities.

- The third category focuses on multi-stakeholder collaborations to enhance transparency, integrity and accountability.

The project explicitly calls for “special consideration” to be given to human rights, with a focus on gender specific interventions (GIZ 2022c). Currently the TIP is introducing data driven approach to curb corruption with a stronger focus on prevention.

School of public action: Western Kazakhstan

Through the provision of public services and the allocation of state resources to fulfil the requirements of the local community, this EU funded project hopes to enhance the quality of life in the rural areas of Western Kazakhstan. Adopting a human-rights based approach, the project centres on the reduction of corruption in public procurement in rural communities, supporting civic initiatives in 48 communities across the region, and the sharing best practices in citizen led human development (D-portal n.d. b).

As a part of the first activities for the programme, training courses were given for the intended beneficiaries: members of local communities. The training resulted in participants increasingly exercising their rights under existing legislation on local self-government, formulating a plan for rural district development and learning about managing the use of funds to tackle local problems (Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Kazakhstan 2021).

Examples of programmes that are focused on human rights and include elements of anti-corruption

Reinforce Human Rights, Rule of Law and Democracy in the Southern Mediterranean

Funded by European Union and the Council of Europe, this overarching programme intends to create a shared legal space between Europe and the Southern Mediterranean, encourage democratic government and enhance related networks (Council of Europe 2020a). The ongoing phase of the project, South Programme IV (2020 – 2022) has “Promotion of Good Governance: Fight against Corruption and Money Laundering” as one of its four components. It seeks to build local and regional capacities to curb corruption and counter economic crime in Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia and Palestine to further the overall goal of reinforcing respect for human rights and enhancement of the rule of law and democracy in the region (Council of Europe 2020b).

Justice, Human Rights, and Security Strengthening Activity (Unidos por la Justicia): Honduras

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) funded programme engages local partners to boost citizen engagement with the security and justice sectors, enhance judicial efficiency and increase community policing effectiveness in Honduras (DAI 2016). The focus on human rights includes institutional strengthening for human rights agencies, protection of human rights defenders and training private sector actors on the subject.

Given that corruption, especially in law enforcement is recognised as eroding trust in justice mechanisms while contributing to rising violence, the project includes anti-corruption components, notably training civil society organisations to conduct social audits to detect corruption (DAI 2016).

Applying a human rights-based approach to local water and sanitation development planning: Philippines

Access to water and sanitation have long been recognised as a crucial human right. In 2010, the government of Philippines designed a programme that focuses on improving access to water and sanitation in waterless municipalities in the country. Going beyond viewing the project through an “economic utility and infrastructure approach”, using a human rights perspective helped identify multidimensional and deep-rooted impediments to water and sanitation access, such as corruption, discrimination, inequality and a lack of accountability (UNDG 2013: 41). Consequently, efforts to address these obstacles were included in water and sanitation policies. For instance, formal accountability measures were formed by establishing a social contract between service providers and users of services, ensuring that local service providers adhere to their duties and that human rights criteria for water and sanitation are satisfied (UNDG 2013: 39).

Other examples of programmes that do not have a clear anti-corruption or human rights focus but which include the two cross-cutting components

COVID-19 Media Support Bangladesh

The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) funded programme has two main outcomes (D-portal n.d. a):

- Enable and strengthen the ability of targeted media houses and news providers to identify, investigate and publish high quality reports, especially on gender equality, labour rights, corruption, environmental harm and climate change.

- Developing the media sector as a whole to provide a conducive atmosphere for investigative journalism on gender equality, labour rights, corruption, environmental damage and climate change.

While the reform target of this project is the Bangladeshi media and the environment in which it operates, the project outcomes are related to strengthening respect for human rights and anti-corruption.

Combating Corruption and Breaching of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedom in Urban and Spatial Planning in Serbia

Funded by the Delegation of European Union to Republic of Serbia, this project aims to (A11 2021):

- advocate for the protection of the right to good governance in the domain of spatial and urban planning, as well as the performance of responsible public administration and the judiciary

- increasing the level of transparency and making it easier for the public to participate in the creation of documents related to spatial and urban planning

- development of participatory capabilities and the exchange of knowledge

The main target of this project is civil society organisations (CSOs). The idea is to eventually increase the capacities of CSOs to “to prevent corruption and act as defenders of the rule of law and public interests in urban planning and management of public goods” in Serbia (A11 2021).

Summary table of project examples

|

Project |

Human Rights – Anti-corruption link |

|

REAP |

Including anti-discrimination, as an important human right is being included in the project aimed at tackling IFFs, tax evasion, and tax avoidance, undermining African countries’ sustainable development. |

|

Indonesia: institutional reform |

Overarching aim of an anti-corruption reform group was to develop, refine and promote ethics codes and integrity norms within institutions (including those dealing with human rights) |

|

Countering corruption in South Africa |

One focus point of the project is to support and protect human rights defenders that are champions of transparency, accountability and anti-corruption activities. |

|

School of public action – Western Kazakhstan |

It centres on the reduction of corruption in public procurement in rural communities via training local communities in exercising their rights under existing legislation on local self-government, formulating a plan for rural district development, and learning about managing the use of funds to tackle local problems. The project aims to apply a human rights based approach in its implementation. |

|

Southern Mediterranean: reinforcing human rights |

Aims to build local and regional capacities to curb corruption while furthering the overall goal of reinforcing respect for human rights and enhancement of rule of law and democracy in the region. |

|

Honduras: Unidos por la Justicia |

There is a focus on institutional strengthening for human rights agencies, protection of human rights defenders while addressing corruption (especially in law enforcement and judiciary). |

- Including, inter alia, the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation.

- The right to non-discrimination guarantees to all persons the right to be free from discrimination in the enjoyment of all other human rights. It protects people from unfavourable treatment or disproportionate impacts on the basis of their identity, status or beliefs (McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021: 11).

- Anti-corruption norms are commonly enforced through criminal justice frameworks, i.e., by criminalising certain conduct in domestic legislation and by prosecuting and punishing perpetrators. This criminal justice approach is reflected in UNCAC and other treaties, as well as in domestic laws around the world (UNODC 2021: 26).