Query

Which strategies are employed by anti-corruption agencies in lower income countries to facilitate public engagement, and which good practices and lessons learned can be identified in promoting effective public participation in anti-corruption efforts?

Background

Anti-corruption agencies and public engagement

Anti-corruption agencies are public institutions mandated to prevent and counter corruption. They originated in South-East Asia in the 1950s and were widely replicated elsewhere throughout the 1990s during a time of increased emphasis on good governance (UNODC 2020:3; UNODC n.d.). They are recommended for state parties under the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNODC 2004) which, under articles 6 and 36, mandates states to ensure the existence of a body or bodies5ec61385ac82 to prevent and counter corruption and provide this agency the necessary independence to do so.

Today, there are an estimated 251 anti-corruption agencies worldwide, with the structure of each agency varying between jurisdictions (Sotola 2025). They often form one part of the institutional anti-corruption framework in a given country, alongside other state units or agencies with a relevant anti-corruption mandate, such as traditional police and criminal investigative units, supreme audit agencies, the judiciary and internal audit, and inspector general officers (Beschel, Chelbi and Schaider 2024). Anti-corruption agencies can generally be categorised as belonging to one of three different models (Sotola 2025:8):

- the standalone model: an agency with a clearly defined mandate, with constitutive laws usually as an act of the parliament, with supporting operational bureaucracy and independence

- the nested model: located within a regular government structure and institution, often created as an offshoot of law enforcement agencies dedicated to anti-corruption

- an ad hoc model: an arrangement in which anti-corruption functions are dispersed across agencies in a non-centralised manner

While the models of anti-corruption agencies vary, their main objectives and functions are similar across jurisdictions. According to the Colombo Commentary on the Jakarta Statement on principles for anti-corruption agencies06eb7908ea16 (UNODC 2020), anti-corruption agencies should be sufficiently empowered to carry out the following four main functions:

Table 1: The main functions of an anti-corruption agency, according to the Colombo Commentary

|

Function |

Description |

|

Prevention |

Anti-corruption agencies should lead efforts to develop, implement, oversee and coordinate national anti-corruption strategies |

|

Education and awareness raising |

Agencies should promote anti-corruption efforts within the government bureaucracy as well as including activities with the private sector and/or the public |

|

Investigation |

Investigate allegations of corruption, whether on its own initiative or in response to a complaint |

|

Prosecution |

Some prosecutorial services have established specialised anti-corruption units and have seconded prosecutors directly to an anti-corruption agency or endowed a new anti-corruption agency with the power to prosecute |

Source: UNODC 2020:8-11.

To carry out these primary functions, anti-corruption agencies work closely with other state institutions and agencies. In addition, they can often be the main counterparts for donor agencies that are engaged in anti-corruption and governance programmes in their jurisdiction (Schütte 2015:2). The other main stakeholder with whom anti-corruption agencies engage to fulfil their mandate is the wider public.

The Colombo Commentary recommends regarding the Principle on public communication and engagement that anti-corruption agencies should communicate with the public regularly to ensure public confidence in their independence, fairness and effectiveness of their work (UNODC 2020:75). This includes groups outside of the public sector, such as civil society, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and community-based organisations (CBOs). The Colombo Commentary also recommends that the public should have access to information on corruption and that anti-corruption agencies should undertake activities that contribute to the non-tolerance of corruption in the wider public, particularly among younger people (UNODC 2020:79).

These activities can be broadly described as public engagement. In the context of anti-corruption, public engagement (or public participation) is defined as (UNODC 2017:9):

‘The role of citizens in addressing and fighting (including detecting and reporting) corruption. Such participation can take place on the personal or individual level, on a more organised level through CSOs, and through the media.’

Public engagement is an essential part of open governance and democracy, while also enhancing inclusivity, improving service delivery and fiscal efficiency, and enabling citizens to seek accountability (Marín 2016:2; de Soysa 2022:10-12). It helps to override corrupt personal interests and general social resignation, apathy and the acceptance of surrounding corruption (Burai 2020:6). Public engagement can also play a vital role in reshaping social norms around corruption, achieving cultural shifts that traditional law enforcement alone may struggle to bring about (David-Barrett et al. 2020:3, 13).

Barriers to public engagement

While each context comes with its own unique challenges, anti-corruption agencies in lower income countries may face additional barriers to public engagement. While issues of state capture, systemic corruption and weak rule of law are not limited to only lower income countries, research suggests that countries with higher levels of inequality are more prone to state capture (David-Barrett 2021) and that lower income countries tend to have a weaker rule of law (World Justice Project 2023:25-30).

Public participation in anti-corruption efforts does not arise in a vacuum and it requires enabling structures and conditions015e23fb7e47 to foster meaningful participation (de Soysa 2022:4). For anti-corruption agencies to conduct public participation activities, they require institutional capacity and financial resources, among other important enablers. As such, low-income countries may face additional constraints in achieving the intended outcomes of public engagement interventions.

Nonetheless, inclusive, bottom-up interventions that address the root causes of corruption may help to shift existing informal practices and social norms that enable corruption (Jenkins, Kukutschka and Zúñiga 2020:16). Political interference and a lack of buy-in from local communities are other reasons why public engagement projects fail more broadly, particularly when local people feel disconnected from the projects (Owonikoko 2021). Moreover, in some regions, anti-corruption agencies are often criticised in view of the disparity between the government’s anti-corruption rhetoric and the impunity enjoyed by public officials (AfriMAP 2015:vi). Moreover, in some countries, there are issues with reaching rural communities, largely due to a lack of widespread transport infrastructure making access problematic (Awuah 2024).

This Helpdesk Answer examines cases of anti-corruption agencies’ public engagement strategies throughout their four primary functions of prevention, education and awareness raising, investigation and prosecution. These examples are largely based in lower to middle income countries to provide inspiration on how to address the potential issues of institutional capacity, systemic corruption, weak rule of law and limited infrastructure that may be present in lower income countries. The final section outlines a range of proposed solutions to support public engagement drawn from various sources. These recommendations, largely stemming from research conducted by civil society organisations (CSOs), should be considered with nuance and adapted to the unique contexts of different anti-corruption agencies.

Strategies of public engagement by anti-corruption agencies

The following sections are based on the four primary functions of anti-corruption agencies. Notably, functions like prevention, education and awareness raising often involve established institutional processes that promote public engagement, unlike prosecution and investigation, which are generally less participatory. The following sections provide several examples of public engagement strategies carried out by anti-corruption agencies, with a particular focus on those in lower income countries. However, because there are limited resources that comparatively assess the effectiveness of various public engagement strategies, this section does not attempt to evaluate the effectiveness of each approach compared to others. Instead, it presents examples that highlight the diverse ways agencies around the world are engaging with the public on corruption and anti-corruption issues.

Prevention

There are several forms of public engagement and a variety of social accountability tools that fall under anti-corruption agencies’ prevention function: complaint mechanisms, giving citizens the opportunity to provide input into the development and implementation of anti-corruption policies and strategies and in the selection of key members of staff at an anti-corruption agency, and providing citizens with information that enables them to conduct monitoring activities.

An important enabling factor for citizens’ ability to support the prevention of corruption is access to information (Article 19 2017). Information enables the public to participate in the scrutiny of government activities and have a say in the development of policies and laws and their enforcement (Article 19 2017).. Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) hosts the JAGA (guard) platform which contains information on corruption, how to report it, an integrity assessment survey that reports on the level of vulnerability and corruption prevention efforts in a specific area and time period, and how citizens can monitor corruption. Moreover, the KPK posts regular news updates on corruption related issues in Indonesia and maintains contact points where members of the public can pose questions to agency staff.

Another form of community monitoring are community report cards (otherwise known as community scorecards). These aim to assess projects and government performance through analysing qualitative data collected from focus group discussions with community members (Burai 2020:9). Citizens are trained to rate the quality of public services and then the government responds to gaps in service delivery, allowing the citizens to report back later on these measures (Burai 2020:9).

For example, in Ghana, the Ghana Integrity Initiative social accountability project (GII-SA) used community scorecard projects to assess the administration of health service funds and the quality of health services for Ghanaians (Baez Camargo 2019:32). This involved the combination of quantitative surveys with village meetings to bring together service users and providers to jointly analyse and resolve service delivery problems, and citizens were empowered to provide immediate feedback to service providers in face-to-face meetings (Baez Camargo 2019:33). While project this was led by a CSO, such interventions could be done in partnership with anti-corruption agencies, particularly in terms of resolving any service delivery problems caused by corruption.

In Brazil, the comptroller general, which serves as the country’s primary anti-corruption agency, created FalaBR, which serves as an integrated ombudsman and access-to-information online platform for the entire federal government and state and municipal administrations, allowing citizens to access information, report wrongdoing and submit complaints on public services (G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group 2022:21). More than 2,500 public bodies and institutions are currently registered in the system. Other anti-corruption agencies are responsible for the asset and interest declarations of politicians and civil servants, which is another transparency tool that citizens can use to monitor public officials (Agence Française Anticorruption 2020:19).

With accessible information, citizens can play an active role in monitoring corruption, anti-corruption efforts and the wider provision on public services that help to both prevent and detect cases (Baez Camargo 2019). The Ugandan Inspectorate of Government (IG), which serves as one of the country’s two main anti-corruption bodies, signed a memorandum of understanding with the civil society organisation Uganda Debt Network to implement social accountability and community monitoring activities (AfriMAP 2015:83). These included building the capacity of communities to monitor government funded projects as well as training regional managers from various community monitoring groups on anti-corruption reporting mechanisms (AfriMAP 2015:83). The IG has also published a Guide on the Role of Citizens in the Fight Against Corruption. This guide clearly explains how citizens can participate in anti-corruption efforts, the anti-corruption agency’s functions, what is corruption, how to report it and to whom, and the contact details of regional offices.

Another way that citizens can support the prevention of corruption is through inputting into national legislation on anti-corruption, to ensure laws are effective and tailored to their contexts. Many anti-corruption agencies lead the process of designing and implementing national anti-corruption strategies (Agence Française Anticorruption 2020:16). Some of these agencies request public input during the formulation and monitoring of these national strategies. For example, in South Africa, the public was encouraged to give input on the national anti-corruption strategy through a communication campaign run by the Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) that invited members of the public, businesses and CSOs to submit electronic input by means of an email address located at the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) (Republic of South Africa 2021).

Anti-corruption agency oversight and appointments

Anti-corruption agencies can also involve citizens in the oversight and appointment of heads or senior roles of anti-corruption agencies. This has the potential to reduce political interference during the selection of the agency’s leadership as well enhancing public trust and legitimacy of the anti-corruption agency more broadly (Schütte 2015). Civil society and the media may be afforded special roles in the appointment process through participating in selection panels or reporting on candidates and their progress through the selection process (Schütte 2015:27).

For example, the Kenyan Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Act of 2011 provides transparency and stipulates a timeline for the process, which requires the call for applications and the shortlist of candidates to be advertised in at least two daily newspapers with national circulation and requiring public interviews with the shortlisted candidates (Schütte 2015:15), allowing for public scrutiny of the process. Indonesia’s law requires the inclusion of civil society representatives on the selection panel for the head of the anti-corruption agency and Integrity Councils, some of which are comprised of civil society and international experts, have been established in Ukraine to vet candidates for key anti-corruption roles (Schütte 2015:15; Biletskyi 2025).

In Sierra Leone, the law requires that anti-corruption agencies create an advisory board on corruption comprising of members who are ‘appointed from among persons representing civil society, professional bodies, religious organizations, educational institutions, chieftaincy institutions and the media, having relevant experience and of conspicuous probity’ (UNODC 2020:78). According to the Anti-Corruption Act (Ministry of Justice 2008:23) the role of the advisory board is to advise the anti-corruption agency on any aspect of its mandate and functions and annually assess its work.

Education and awareness raising

The education and awareness raising function of anti-corruption agencies includes public engagement as its key component. According to Boehm and Nell’s brief on anti-corruption education and training (2007), anti-corruption education should promote a deeper understanding of how anti-corruption works, its causes and consequences and how it unfolds across countries, regions and institutions. It should also provide an analytical framework and hands-on skills on how to address corruption in practice (Boehm and Nell 2007).

The majority of anti-corruption agencies conduct education and awareness raising with the public, in both high and lower income countries. These activities engage a range of stakeholders using a variety of different online and offline platforms. For example, the Agence Française Anticorruption (AFA) reported that in 2020 it conducted 20 awareness raising activities for schools and training institutions including the National School for the Judiciary and the French Bar School (AFA 2020:34). These were focused on preventing and detecting corruption (AFA 2020:34). Additionally, the AFA continued its MOOC (massive open online course) on preventing corruption in local government, which more than 22,000 people had taken since it started in 2018 (AFA 2020:34).

It is also important that anti-corruption agencies make their services and contact details available to the public. A service charter (also known as a citizen’s charter) is ‘a public document that sets out basic information on the services provided, the standards of service that customers can expect from an organisation, and how to make complaints or suggestions for improvement’ (Loffer et al. 2007:15). Citizens charters are often hosted on websites by anti-corruption agencies and inform citizens about their rights and entitlements as service users and the remedies available to them if the standards (timeframe and quality) are not met (Burai 2020:9).

According to Baez Camargo (2018:2), service charters are considered a social accountability tool in themselves as they inform citizens about their rights and entitlements, the standards they can expect and the remedies available for providers’ nonadherence to standards. This in turn can help to strengthen the accountability of the institution, resulting in better service delivery by the anti-corruption agency and more effective anti-corruption efforts. Well-articulated citizen charters like these can enhance public understanding of an anti-corruption agency’s mandate and engagement mechanisms, while also serving as a preventive tool by presenting this information in a clear and accessible format. As an example, the Anti-Corruption Bureau in Malawi sets out its mission, mandate, core values, functions, clients, contact details of each office, service and standards of each office, clients’ rights and responsibilities, how to provide feedback and the frequency of their monitoring activities of their work on their website (Anti-Corruption Bureau Malawi 2018).

Anti-corruption agencies can reach a wide variety of different stakeholders through their education and awareness raising programmes. Through its Integrity Directorate and Media, Communication and Public Relations unit, for instance, the Jordanian anti-corruption agency in 2022 organised 122 awareness lectures catered to different stakeholder groups, including health institutions, schools and universities and civil society organisations (Beschel, Chelbi and Schaider 2024:10). It relies on social media as well as SMS text messages to target different age groups. For its part, the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission holds educational activities that include conventions and forums to bring together leading experts on anti-corruption, roundtable discussions with public and private agencies, and representatives of organisations, community associations and industry players to discuss cross-agency and community cooperation, workshops and seminars, exhibitions, and talks and briefings (MACC n.d.).

Anti-corruption agencies have also adapted their education programmes in situations of fragility, such as wartime. The National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine provides video lessons, tests and interactive learning on their website for the public on a variety of different topics, ranging from integrity during wartime, the e-reporting of political parties, conflict of interest, integrity in the police and integrity in the judiciary (NAZK no date).

Additionally, the anti-corruption agency in Kenya has extended education activities to reach rural communities. The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) ran county based outreach clinics that: develop and disseminate information, education and communication material; mainstream anti-corruption content in formal education systems: promote integrity clubs in schools; and train various interest groups (AfriMAP 2015:14). Integrity training can be integrated into early childhood education, such as Indonesia’s KPK which has developed learning material to support schools to instil humanitarian values and empathy (G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group 2022:24).

Working with women and young people

It is important that anti-corruption agencies engage with women and young people, as both groups are disproportionately impacted by corruption (McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021). To address the specific forms of corruption that impact these groups, it is recommended that states design targeted solutions to address these, that are context-specific and designed in consultation with affected groups (McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021:81).

An approach taken by the KPK was to support the development of a network of women taking action against corruption, known as I am a Woman against Corruption (SPAK) (Dyer 2017). This was based on research conducted by KPK between 2012 and 2013 which found that only 4% of parents taught honesty values to their children in relation to their daily life, leading KPK staff to focus on the education of parents, in particular women who are considered to hold an influential position in the family and households in Indonesia (Dyer 2017:6-9).

SPAK is a social movement and form of collective action that brings together women from a range of different social backgrounds to take part in various activities, often in support of the KPK, as well as train others to join the movement (Dyer 2017:6-7). As one of the outcomes of the initiative, many women reported understanding their rights more, particularly regarding the small payments of gratification that are often expected regarding their children’s education, or for traffic offences or to speed up official document and licences in local government offices (Dyer 2017:21).

The UNDP (2022:22) recommends that anti-corruption agencies work on engaging stakeholders, in particular civil society, to create a strong basis of support. This can also be particularly useful when engaging with groups such as women and young people, particularly at the community level. Anti-corruption agencies in both Jordan and Kuwait have also had recent success in collaborating with anti-corruption CSOs such as Transparency International chapters and the UNCAC Civil Society Coalition on assessments of national anti-corruption legislation and monitoring government performance in public service delivery (Beschel, Chelbi and Schaider 2024:11).

Finally, the use of technology is particularly useful in engaging young people with anti-corruption efforts. The G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group (2022:31) cites the example of Brazil where the anti-corruption agency has developed an online game for teenagers called the Citizen Game, which focuses on real-life experiences to help foster ethical behaviour and civic engagement. Similarly, the anti-corruption agency used social media to enable interactive online debates between the youth and commission leaders (UNODC 2020:79).

Encouragingly, there are indications that anti-corruption agencies are working to give greater consideration to women and groups at risk of discrimination. Aminuzzaman and Khair’s (2017:19) assessment of anti-corruption agencies in the Asia Pacific found a moderate positive trend in agencies compiling gender-sensitive demographic information that allows them to monitor how corruption and their services affect women differently.

Investigation

The primary way that citizens can engage with an anti-corruption agency’s investigation function is by alerting them to suspected instances of corruption. There are generally three different avenues for the public to report to: 1) internal reporting within their workplace; 2) external reporting to a regulator, law enforcement agency or other specific authority; and 3) to the media or other public platform (UNODC n.d.). Anti-corruption agencies fall under the second avenue and often provide the main state-run reporting avenue available to whistleblowers.

In 2007, Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) developed an online whistleblower system for anonymous complaints against commission staff and later expanded it to include all corruption complaints (Kuris 2012:11). The KPK in Indonesia has a webpage on public complaints, that describes forms of corruption, cases that the KPK can handle, how to submit a complain of corruption, and the protection provided to those who have submitted complaints which, in the most severe cases, can entail physical protection (KPK 2017). Evidence suggests that community participation supports the KPK’s efforts to identify corruption crimes that occur in society (Chadidjah 2022). Public submissions of information accompanied by strong supporting evidence reportedly assist the KPK to resolve corruption cases (Chadidjah 2022). There are a number of different methods by which citizens can report corruption complaints: through postal mail, in person, telephone, text message or an online complaint system application (Chadidjah 2022).

The KPK also supports citizen participation in audits (Chadidjah 2022:28). Subjects of public claims or complaints include service performance; allegations of general crimes; allegations of corruption, collusion and nepotism; problems with the potential to cause social and environmental vulnerabilities; deviations that cause state financial losses; and allegations of abuse of authority (Chadidjah 2022:28).

The EACC in Kenya has an online whistleblowing system that facilitates anonymous reporting, which is supported by German bilateral aid (AfriMAP 2015:40). It also has a public feedback mechanism where, after a person has submitted a report of corruption, they have the option of creating an anonymous postbox (AfriMAP 2015:36). This allows the individual to access feedback from the EACC on the progress of the report or receive messages in case there is a need for more clarification and feedback, and all messaged are encrypted, allowing the communication to be anonymous (AfriMAP 2015:36).

Finally, CSOs can pass on instances of corruption that are reported by the public to anti-corruption agencies, to either initiate or support an investigation. As an example, Transparency International Zambia (TI-Z) runs an Advocacy and Legal Advice Centres (one of more than 60 worldwide that are based in Transparency International national chapters) which is open to the public to report instances of corruption. Between January and October 2024, TI-Z reported that they received 149 reports, three quarters of which were corruption reports (TI-Z 2024). 35 of these reports were referred to authorities, including the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) and the Office of the Public Protector (OPP) (TI-Z 2024).

Prosecution

While not every anti-corruption agency has prosecutorial powers, Messick (2015) contends that those with the responsibility for investigating and prosecuting corruption are more likely to be more effective in enforcing anti-corruption laws. Messick (2015) argues that this is due to corruption offences being complex, meaning that the prosecutor should be involved in the investigation of the case so that they can ensure that the evidence collected will be admissible in court. While public engagement is not directly part of the prosecution of corruption cases, anti-corruption agencies can raise awareness of successful cases to increase public trust and understanding of their work.

Indonesia’s KPK has the power to investigate and prosecute cases that involve law enforcement or public officials, give rise to particular public concern and/or involve losses to the state budget of at least Rp 1 billion (US $116,000) (Schütte 2012:43). The KPK has had a track record of successful prosecutions, which generated positive responses from the public regarding anti-corruption efforts more broadly2f984e8e9fe4 (Kuris 2012:14). This public support resulted in even more investigative tips, and civil society began trusting the KPK with evidence that was collected at the grassroots level (Kuris 2012:14). Public support generally helped the KPK to develop a strong relationship with civil society, protecting it from political attacks and unifying the anti-corruption movement across the country (Kuris 2012:17). Additionally, the anti-corruption agencies of Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Ukraine and the United Kingdom all publish reports on their progress on corruption complaints, investigations and convictions on their websites (UNODC 2020:74).

Beschel, Chelbi and Schaider (2024:8) find, in their analysis of anti-corruption agencies based in the Middle East and North Africa that the anti-corruption agency of Saudi Arabia saw a large increase in corruption complaints after the publicised imprisonment of senior officials on corruption charges. This led to a rise in corruption complaints from citizens throughout the country, across rural and urban divides, and the authors suggest this may have been due to the awareness raised from high-profile cases and trust that there will be a follow-up to reports.

Assessments of anti-corruption agencies’ engagement of citizens

While there are no comparative assessments of the effectiveness of any specific mode of public engagement, there are several assessment tools that have been developed by international and civil society organisations for anti-corruption agencies more broadly that include indicators measuring levels of public engagement.

Transparency International’s assessment toolkit on public participation in budget processes has several relevant indicators to measure a public institution’s readiness to begin public engagement efforts. Part A of the assessment tool measures the public participation readiness of a public institution through a range of proxy indicators to assess the extent to which the pre-conditions and enabling factors of meaningful public participation are met (de Soysa 2022:18). These include the assessment pillars on political will, legal mandates and operational frameworks, and civic space (de Soysa 2022:27-43). Such indicators can be used to measure an anti-corruption agency’s ability to begin meaningful public engagement interventions and point towards areas that require improvement in order to ensure effective public engagement strategies.

The UNDP’s (2011) methodology to assess the capacity of anti-corruption agencies includes measurements on the organisational level of agencies, including indicator 6 on knowledge and information management and indicator 7 on communication through a website, annual reports and press releases (UNDP 2011:46). However, this assessment tool does not provide detail on more specific forms of public engagement to support the assessment of an agency’s overall effectiveness.

Transparency International’s methodology to assess the strengths and weaknesses of anti-corruption agencies includes 50 indicators. Those pertaining to public engagement include: indicator 25 on whether the agency identifies gender in compiling corruption complaints and monitoring corruption trends; indicator 26 on the average proportion of the agency’s operating expenditure allocated to public outreach and prevention; indicator 30 on the agency’s plan for outreach and education and its implementation; indicator 31 on the agency’s collaboration with other stakeholders in outreach and education activities; indicator 33 on the dissemination of corruption prevention information and use of campaigns; and indicator 34 on the agency’s use of its website and social media (Aminuzzaman and Khair 2017:34-43).

Aminuzzaman and Khair (2017)applied the assessment to anti-corruption agencies in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Indonesia, Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka and found that some agencies had developed an anti-corruption strategy and plans to generate wider community awareness and engagement, whereas others in the region were still in the process of doing so (Aminuzzaman and Khair 2017:19). For almost all, the budgetary allocation for prevention, education and outreach was deemed less than adequate. Bhutan’s anti-corruption agency scored most highly in terms of public engagement.

Finally, a recent framework developed by Schütte and David-Barrett (2025) on assessing the compliance of anti-corruption agencies with the Jakarta Principles. It includes questions on whether the anti-corruption agency complies with the Principle to formally report on their activities to the public, specifically, whether the anti-corruption agency includes information on its performance broken down by specific mandate and expenditures and whether any annual report or other report is submitted to a public body for public discussion (Schütte and David-Barrett 2025). It also assesses compliance with the Principle on public communication and engagement through whether anti-corruption agencies regularly communicate with the public, whether they have their own website, do they have multiple channels for the public to report corruption to, and whether it undertakes any public surveys in relation to anti-corruption in the country (Schütte and David-Barrett 2025).

Good practices in public engagement

A significant portion of the literature reviewed in this section is derived from lessons from projects led by civil society and non-governmental organisations. However, the insights generated through their research may be valuable for anti-corruption agencies operating in lower income countries as these anti-corruption and development projects often involve rural communities. Given the limitations of this Helpdesk Answer, it does not consider the added complexities of the power dynamics between local communities and a government agency (such as an anti-corruption agency). Therefore, caution should be applied when considering public engagement in anti-corruption efforts and projects led by government agencies, as opposed to those led by civil society.

A phased approach

The phased approach refers to a public engagement project includes phases that are sequenced during the planning, implementation and monitoring. This approach helps to ensure that projects are transparent and provide space for participatory approaches and feedback from citizens at each distinct step in the process.

Most importantly, prior consulting activities with target communities should be conducted to document the priorities of the target groups and the characteristics of the local environment to prepare a needs-tailored programme, training or intervention (Boehm and Nell 2007). Implementation of anti-corruption interventions adapted to specific country conditions and contexts is key (Pompe and Turkewitz 2022) and provides communities with a sense of ownership of the projects (Burai 2020:22).

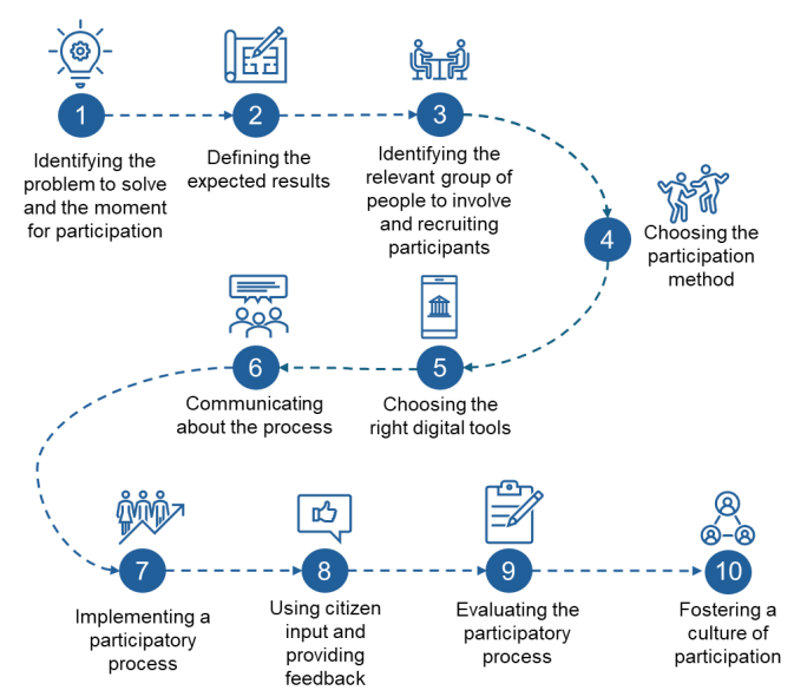

Morisson and Ferrario (2025) illustrate a ten-step phased pathway for implementing a public engagement project:

Figure 2: Ten-step path for planning and implementing a citizen participation

Source: Morisson and Ferrario 2025:18.

Incentivising public engagement

Farag (2018) discusses the methods of incentivising citizens to engage in anti-corruption movements and interventions through the lens of rational-choice theory, internal incentives and social incentives based on people’s need for belonging and trusting others in order to fit within the larger society. Through these lenses, he sets out the following approaches under each to suggest ways to engage citizens in anti-corruption efforts:

Table 2: Ways to increase public engagement

|

Rational incentives |

|

|

Use quick wins to demonstrate impact |

Inform people when public authorities took on board some of their suggestions or demands and celebrate these moments |

|

Make engagement informative and valuable |

Offer information sessions and training programmes on issues that people would value or on particular skills that people lack |

|

Offer rewards and limit costs |

Make reporting corruption cost-free by providing a toll-free hotline, an email address, or other modes of messaging |

|

Take people’s concerns seriously |

Inform people engaged in your activities about what legal protection they have and about the assistance you could provide. To encourage engagement, especially in the early phases, use low-risk actions such as radio call-in shows and petitions |

|

Do not make engagement a waste of people’s time |

Make reporting of corruption less time consuming by designing a clear and concise reporting process and by removing any unnecessary steps |

|

Internal incentives |

|

|

Subject people to the behaviour you want them to adopt |

Expose people to messages on commitment, participation and engagement |

|

Focus on what people will lose, not what they will gain |

Focus your communication on how not reporting corruption might result in the loss of a particular amount of money that would otherwise be spent on developing poor areas. Get people to understand how their non-engagement might result in worse public services |

|

Leverage the power of habit to engage people |

Target those who have already engaged or volunteered in public life. Ask local NGOs to organise a meeting with their volunteers. Build on already existing habits. If a group of activists/elders meet every week/month at a certain place, schedule your activity just before that time at the same or a nearby venue |

|

Play on the self-image of people |

Focus your communication on encouraging people to become corruption fighters or whistleblowers rather than on the act of whistleblowing or fighting corruption |

|

Get people to publicly commit to engage in the fight against corruption |

Get people or public authorities to declare their public commitment for engaging in the fight against corruption |

|

Ask people to develop a plan if you want them to follow through |

If people commit to engage or participate in an event, give them a paper and pen and ask them to write the date and time of the next meeting |

|

Social incentives |

|

|

Make engagement personal, fun and social |

Let people document their stories. Teach them the basics of storytelling and ask each of them to document their work either by participatory video, drawing or writing |

|

Show people that others are already engaging and they will follow |

Highlight the stories of whistleblowing champions |

|

Let people nudge others to engage |

Direct your communication and messaging around whistleblowing in a way that could get people to nudge others to report corruption to anti-corruption agencies |

Source: Adapted from Farag 2018.

Sustainability of public engagement

Numerous studies have explored ways to ensure the sustainability of public engagement projects, though these evaluations primarily concentrate on initiatives led by CSOs and donors. For example, Else et al. (2024:iii) in their analysis of public engagement case studies in Nigeria suggest that interventions developed and implemented in close partnership with local organisations and community members may be well positioned to foster community driven efforts that can be sustained in the longer term. This requires investments in relationships that enable interventions to be sustained over the longer term.

The G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group (2022:15) highlights the importance of engaging youth in anti-corruption efforts, particularly to ensure the sustainability of anti-corruption interventions. They group notes that this means investing in the capacity of teachers and academics to ensure quality education on corruption (G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group 2022:29). While it is considered very difficult to quantify the effects of anti-corruption training, it can be provided at a relatively low cost and still have potentially important effects (Boehm and Nell 2007). Training in schools and universities is seen as sustainable initiatives as students may eventually work in public administration or the private sector where they can effectively deter or prevent corruption in the future (Boehm and Nell 2007).

Moreover, it is important to provide lifelong learning opportunities on the themes of ethics and integrity, meaning that these topics should be taught both at schools as well as covered in courses delivered in professional settings in both the public and private sectors (G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group:26).

Finally, Else et al.’s (2024) analysis of Nigerian community engagement projects finds that long-term community driven engagement requires funding for long-term sustainability. Respondents to their surveys reported pursuing diversified revenue streams, which included paid legal and consultancy fees and seeking out new grants (Else et al. 2024:21). There is some evidence that public engagement efforts are sustainable to a certain extent, but this is reliant on local stakeholders’ ability to: 1) engage in continued collaboration and network-strengthening activities; 2) strategically scale efforts to deepen community engagement and expand activities to other communities; and 3) access consistent funding streams and operational support (Else et al. 2024:22).

Potential unintended consequences of public engagement

There are several reasons highlighted in the literature as to why public engagement can fail. In their policy brief on public engagement in governance processes, Morrison and Ferrario (2025:4) include the following common pitfalls:

- Poor planning for the consultation with citizens, including non-representative sampling or the domination of certain groups that can skew results, or planning consultations at inconvenient times or locations that can prevent key demographics from participating. This can include the use of an inappropriate venue or language.

- Poor facilitation, including facilitators lacking prior understanding of the level of knowledge and expertise of the participants and/or if verbal and dynamics of the room are not considered

- A lack of promotion and incentives, which includes making potential participants aware of the benefit of participating

- Too much political influence on the discussed theme, which may increase distrust in the exercise (Morisson and Ferrario 2025:4).

Burai (2020:13) notes that, in countries with high levels of corruption, approaches based on collective action theory may fail if authorities impose rules without effective monitoring and sanctioning, and the measures do not transform social norms. Moreover, increased transparency revealed more corruption, making more people aware of the issue while potentially opening the door for corrupt actors to take part in more corrupt practices (Burai 2020:13).

Similarly, messaging on the pervasiveness of corruption can backfire, particularly if citizens perceive corruption as an expected behaviour and become disincentivised to act against corruption (Persson et al. 2013). Some studies suggest that this can be mitigated somewhat by positive messaging that highlights progress in addressing corruption (Ishikawa 2024:9). Nonetheless, a review of other studies by Peiffer and Cheeseman (2023) find the opposite, that even ‘upbeat’ messaging on anti-corruption that focuses on the progress made in controlling corruption can make the situation worse. Therefore, the authors conclude that testing anti-corruption messaging before presenting it to the wider public is necessary to mitigate unintended consequences, (Peiffer and Cheeseman 2023:13). An important component of raising awareness to anti-corruption efforts is to highlight the relevance of corruption as a local issue that influences the lives of citizens and their peers (Ishikawa 2024).

- This is often interpreted as mandating that the government set up a new anti-corruption agency, although these functions can also be covered by one or more (existing) government agencies or departments.

- The Jakarta Principles (2012) set benchmarks for the independence and effectiveness of anti-corruption agencies. The Colombo Commentary (2020) is a practical guide to support the implementation of the Jakarta Principles.

- According to de Soysa (2022:4) these include availability of information to the public, strong political will, appropriate enabling legal and bureaucratic frameworks, adequate resources and open civic space.

- An example of public support for the KPK is when CSOs and student groups started collecting money for the construction of a new KPK building (Schütte 2013). Individual donations were accepted and in-kind donations such as bags of cement, bricks, wood and iron bars were given. While there have been debates in the country as to whether public donations can be used to help fund the agency, these were eventually accepted, and parliament eventually had to give in and approve the budget for a new KPK building (Schütte 2013).