Why and how the SPAK Courts were established

Following the landslide victory of a coalition led by the Socialist Party (PS-LSI) in the parliamentary elections of 2013, the Albanian government initiated a package of constitutional reforms aimed at countering pervasive corruption within the judiciary and bringing the country closer to the European Union (EU). The constitutional reform package comprehensively altered the permanent institutional arrangement of the judiciary and prosecution services in Albania. Part of the new system is a separate structure for the investigation, prosecution, and adjudication of corruption and organised crime cases. The Special Courts against Corruption and Organised Crime (Gjykatat e Posaçme kundër Korrupsionit dhe Krimit të Organizuar), known as the SPAK Courts, are an integral component of this new structure (Hoxhaj 2020).

The overall architecture of the reform was devised by a technical group of Albanian and international experts that was established under the auspices of Parliament (Ibrahimi 2016). The impetus for the special anti-corruption structure came from this expert group, which defined the creation of such a structure as one of the strategic objectives of the justice reform (GHLE 2015b).

The main rationale for establishment of the structure was to strengthen the integrity and independence of the authorities responsible for processing corruption cases. The expert group emphasised that the structure should be independent from the external influence of criminal and political groups and should ensure that senior prosecutors would not be able to influence ongoing cases of lower-ranking prosecutors. Most notably, the group recommended actions to rigorously vet the integrity and assets of the structure’s officials in order to leave no room for the recruitment of corrupt persons. In addition, the officials should be subjected to continuous monitoring (GHLE 2015b).

International stakeholders substantially influenced the establishment of the special structure. The expert group included representatives of international service projects, and it modelled the special structure on existing anti-corruption institutions in Europe (Vorpsi 2016).4bf538cbc15b In addition, the Venice Commission, officially the European Commission for Democracy through Law, a constitutional expert body of the Council of Europe, made several recommendations on the design of the structure that led to adjustments. Essential to the success of the overall reform process has been its continued promotion by the EU and the United States, which have provided support through various initiatives.92817ffec867 Crucially, Albania was granted EU candidate status in June 2014, but the start of accession negotiations was made conditional on sustained progress on justice reforms and actions to counter organised crime and corruption. This has created considerable pressure on the parliamentary opposition, which, albeit initially reluctant about the reform, unanimously supported the constitutional amendments when they were adopted on 22 July 2016 (Hoxhaj 2021).

Key features of the SPAK Courts

Structure and jurisdiction

The criminal court system in Albania is structured in three tiers. Prior to the establishment of the SPAK Courts, the judiciary processed each corruption case in one of the following ways, depending on the identity of the defendant:

- Low-level corruption cases were adjudicated by the ordinary courts. Such cases came first before the competent district court and could then be referred to an appellate court. The High Court served as the cassation instance.

- Before 2014, the ordinary courts also handled high-level corruption cases. However, following an amendment of the Criminal Procedure Code in 2014, high-level corruption cases involving senior officials, local elected officials, and justice officials were processed in first and second instance by the Serious Crime Courts, a court structure specialised in a wide range of serious offences.ac80bcb30159 It has since been abolished.

- All offences, including corruption, committed by a narrow group of the highest-ranking officials (such as the president or prime minister) were assigned to the original jurisdiction of the High Court by Article 141(1) of the outdated Constitution.

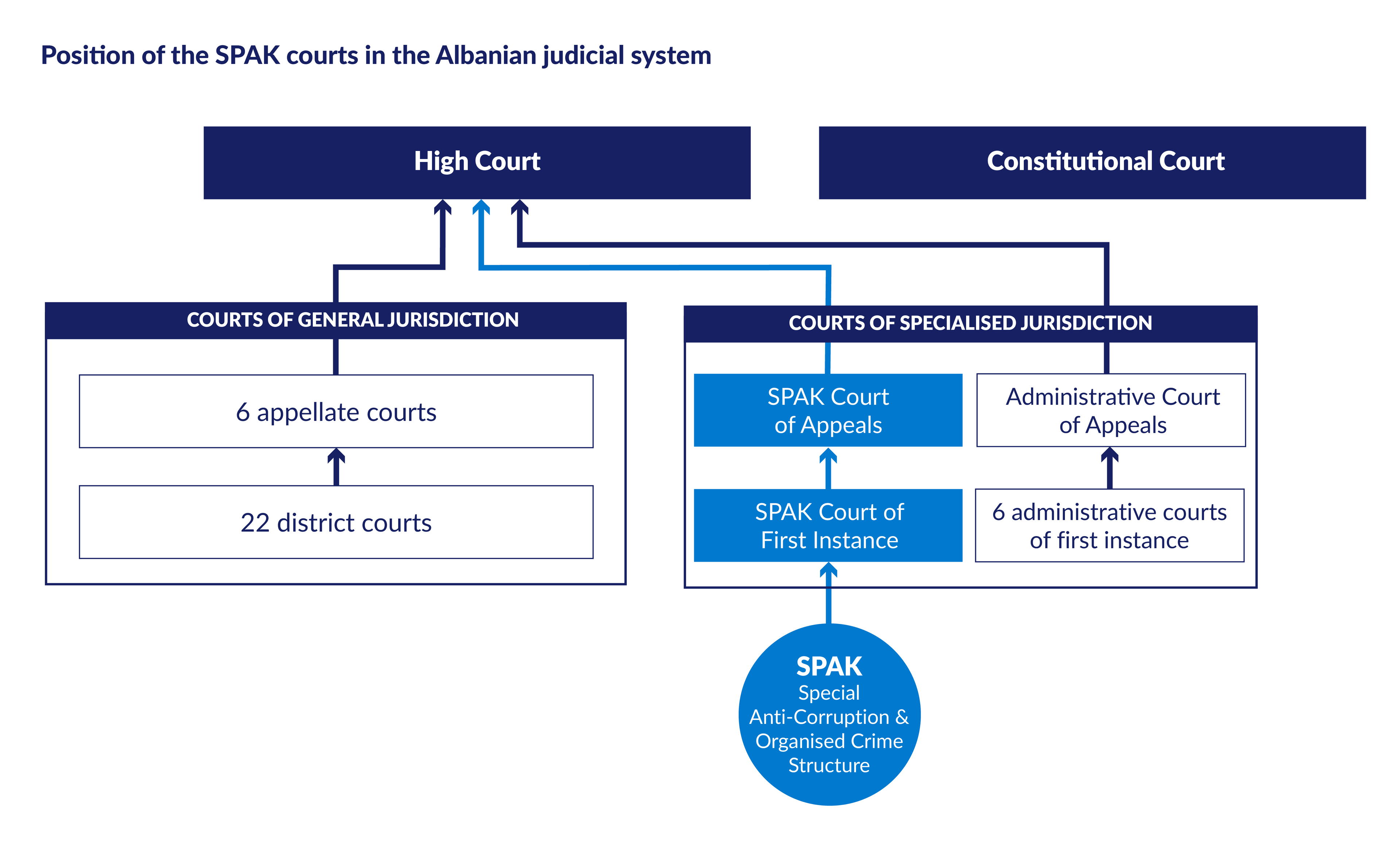

With the start of their operations on 19 December 2019, the SPAK Courts took over the Serious Crime Courts’ premises and much of their staff. Like their predecessors, the SPAK Courts comprise a first and an appellate instance with nationwide jurisdiction, with the High Court acting as the cassation instance. The SPAK Courts decide most cases in a panel of three judges.c038e4d7654d Attached to the SPAK Courts is the Special Anti-Corruption and Organised Crime Structure (SPAK). It consists of a prosecutorial authority known as the Special Prosecution Office, which is independent from the rest of the prosecution services, and a subordinated investigation unit, the National Bureau of Investigation. SPAK has exclusive responsibility for the investigation and prosecution of cases within the jurisdiction of the SPAK Courts.

Figure 1: Position of the SPAK Courts in the Albanian judicial system

Article 135(2) of the Constitution gives the SPAK Courts competence to adjudicate (a) corruption, (b) organised crime, and (c) charges against an extended group of the highest-level officials.bbbe71aa678e The competences of the SPAK Courts are further specified in Article 75/a of the Criminal Procedure Code, which interprets ‘organised crime’ to include offences committed by terrorist groups.3090484808be Therefore, most of the corruption-related competences previously divided among three pillars of the judiciary (ordinary courts, Serious Crime Courts, and High Court) were concentrated in the SPAK Courts. While the SPAK Courts do not specialise exclusively in corruption cases, such cases make up a substantial part of their docket. Of the 70 cases with 260 defendants submitted by the Special Prosecution Office to the SPAK Courts in 2020, 53 cases with around 100 defendants related to corruption (SPAK 2020).c627324b7275

Until recently, there was no limitation on the magnitude of corruption offences subject to the jurisdiction of the SPAK Courts. However, an amendment to the Criminal Code on 23 March 2021 introduced monetary thresholds of ALL 50,000 (around $500) for certain corruption offences involving public officials, and ALL 800,000 (around $7,500) for corruption in procurement.86cbcfd9a788 Corruption cases below these thresholds are now processed by the ordinary courts.

Status and appointment of SPAK judges

The law requires a minimum number of 16 SPAK judges in first instance and 11 in the appellate instance. Judges of the SPAK Courts receive additional compensation, are afforded special security, and are entitled to earlier retirement than their peers.1937684ec527 Furthermore, Article 135(4) of the Constitution provides that they can only be dismissed from office by a two-thirds (instead of a simple) majority of the High Judicial Council, a constitutional body responsible for the governance of the judiciary that consists of six judges chosen by the courts and five lay members appointed by Parliament.

Permanent judges of the SPAK Courts are appointed in a promotion procedure managed by the High Judicial Council. Judges who apply to open positions are assessed by the Council with reference to their experience, ethics, and seniority. To be eligible for assignment, judges need several years of experience.eff0e4ec9af2 In addition, the personnel of the whole special structure are required by Articles 135(4) and 148-dh(5) of the Constitution to undergo a security check prior to appointment and consent to periodic monitoring of their financial accounts and personal telecommunications.f2d6c0e70dc7 Their close family members must consent to monitoring as well.a89179e86005

Periodic monitoring of telecommunications: Viable innovation against ‘telephone justice’?

The most remarkable feature of the SPAK Courts in international comparison is a periodic review mechanism for monitoring their personnel’s communications on the basis of the Constitution, provided alongside periodic reviews of these individuals’ financial accounts.28b49076a0e4 The impetus for this monitoring mechanism came from the expert group that devised the overall architecture of the reform, which recommended legal amendments to ‘create a special Mechanism (Court Watchers) with legal authority to accept corruption complaints or unethical behavior by judges and prosecutors, who may actively monitor the courts’ (GHLE 2015b). The monitoring was thus already provided for in the initial draft of the constitutional reform.

The monitoring mechanism is not operational yet, and the implementing rules for it seem to still be in development. However, Article 42 and Chapter VIII of Law 95/2016 provide a framework for the monitoring, as follows:

- Upon assuming office, each member of the special structure is provided with a mobile phone and an email address that they must use for all electronic communications. Their telephone calls, text messages, and email communications are monitored by an officer of the National Bureau of Investigation (the investigative unit of SPAK).

- The investigator is under the direct control and monitoring of a SPAK prosecutor, who is specifically assigned by lot to this task on a monthly rotation. The investigator reports any information that gives rise to a reasonable suspicion of corrupt or criminal activity to the responsible prosecutor.197c3ebe3257 Based on the report, the prosecutor independently opens an investigation.

- The investigator can access the declarations on assets and associations of the special structure’s personnel and can cooperate with the State Intelligence Services. Any records that give rise to a reasonable suspicion are maintained by the investigator for two months, unless a SPAK prosecutor orders them to be maintained longer.8f36c5974431 All other records must be destroyed within three days.

- Listening to telephone conversations involving persons who have not previously consented to the monitoring (as personnel of the special structure and their family members must do) is prohibited. However, if the investigator has reason to believe that the interception will provide evidence of a criminal act, he or she must immediately contact a SPAK prosecutor to obtain judicial authorisation. While close family members waive their privacy rights, the monitoring of a family member’s telephoneb26104cef365 requires reasonable suspicion that it is being used to avoid the supervision of staff. An isolated review of a family member’s telephone must be reported by the investigator to the responsible prosecutor; if continued, it requires the prosecutor’s authorisation.

The outlined framework not only establishes a system of internal checks for the special structure, but also seems to function as a kind of Benthamian panopticon: since individuals do not know when they are being monitored, they are incentivised to regulate their own behaviour. The investigator does not have to review all communications of the special structure’s personnel to ensure integrity of conduct.

Although such a mechanism represents an innovative instrument against informal influence or pressure exerted on judicial authorities by outside actors (colloquially known as ‘telephone justice’), it poses significant challenges related to privacy rights and to the independence of SPAK prosecutors and judges. Notably, the Venice Commission emphasised that the constitutional provision for periodic review of telecommunications does not give carte blanche to the security services to intercept all communications of specialised judges and prosecutors. Rather, the monitoring should be clearly described in the law and should be accompanied by adequate and effective procedural guarantees. Specifically, the Commission recommended judicial authorisation for the monitoring and special protection of the privacy of family members as well as those who may accidentally be affected by surveillance measures (Venice Commission 2016).

While it appears that there are plans to have the implementing regulations limit all monitoring without judicial authorisation to metadata, it would be preferable to explicitly include such a limitation in the law itself. Because the monitoring system seems to cover electronic communication exclusively, it also remains to be seen how effective it will be in practice.

Challenges to the operation of the SPAK Courts

Controversy about appropriate scope of jurisdiction under the new Constitution

Even before the establishment of the SPAK Courts, there was controversy about what types of corruption cases the new institution should focus on. According to the initial draft of the constitutional reform, the special structure was only to be competent for the adjudication of high-level corruption cases involving judges, prosecutors, and senior officials, mirroring the jurisdiction of the former Serious Crime Courts. Low-level corruption cases would be handled by the ordinary courts.

However, this limitation of jurisdiction was not in line with earlier recommendations made by the expertgroup that devised the reform. The group believed that the ordinary courts should not be given jurisdiction over low-level corruption cases due to insufficient specialisation. Beyond that, it found that the division of jurisdiction would create potential for jurisdictional conflict (GHLE 2015a). Possibly for these reasons, the constitutional legislator ultimately decided not to limit the remit of the SPAK Courts over corruption offences.

Recently, the issue has moved to the legislative level. As already mentioned, in March 2021 Parliament detached SPAK’s jurisdiction somewhat from the constitutional wording by introducing monetary thresholds of around $500 and $7,500 for certain corruption cases. Initially proposed thresholds were as high as ALL 5,000,000 (about $50,000). In the run-up to the reform, the chairman of the High Prosecutorial Council (the equivalent of the High Judicial Council for the prosecution services) also called for further narrowing the special structure’s focus to corruption offences committed by senior state officials. On the other hand, Parliament extended the special structure’s jurisdiction by adding electoral corruption to its remit on 17 December 2020, following the transfer of high-profile electoral fraud cases from the Special Prosecutor’s Office to local prosecutors by the SPAK Courts. Three months later, Parliament lifted a statutory prohibition on extending the SPAK Courts’ competences beyond the constitutional wording. The prevailing tendency still seems to be to shift the focus of the SPAK Courts to high-level corruption, moving them closer to more specialised institutions in the region, such as the High Anti-Corruption Court in Ukraine.

Some critics doubt whether the legislative changes to the SPAK Courts’ jurisdiction are constitutional. This illustrates that constitutional entrenchment of anti-corruption courts, while having advantages, brings with it rigidity that can result in legal friction. On the positive side, entrenchment can serve to insulate the specialised courts from other parts of the justice system and from changing political majorities, as well as to signal commitment to reform stakeholders (Vorpsi n.d.). In principle, it also lowers the potential for constitutional conflict, which has occurred in some other jurisdictions that have established anti-corruption courts. However, if certain components of the court’s institutional design that are laid down in the Constitution prove to be disadvantageous, the process for adjusting them is much more difficult than it would be were the courts not entrenched in the Constitution.4c0cb9a49c6e For this reason, policymakers may decide to change the implementing legislation without changing its constitutional foundations, possibly putting them in conflict with each other.

Impact of vetting on the recruitment of judges

The same reform package that established the SPAK Courts introduced a temporary vetting mechanism called the ‘transitional re-evaluation process’. It consists of an asset, background, and proficiency review of all incumbent judges and prosecutors in Albania by an independent commission (Mykaj 2020).

The re-evaluation process has led to considerable staff shortages at the Albanian higher courts, also affecting the operations of the SPAK Courts. On the one hand, the process resulted in an outflow of judges from the SPAK Courts: because most sitting High Court judges were dismissed or resigned during the vetting process,9fd9ba8610bf several SPAK judges were promoted to the High Court. On the other hand, the candidate pool for the SPAK Courts has been cleared by the termination of around two-fifths of all Albanian judges and prosecutors as well as several judges of the former Serious Crime Courts in the course of transitional re-evaluation. In addition, another two-fifths of Albanian judges are not eligible for a position in the SPAK Courts because they have yet to undergo vetting, which currently serves as the security check on the special structure.b649356a8988 Adding to the difficulty is the fact that the candidate pool for the SPAK Courts cannot be replenished quickly because several years of experience are required for office. Finally, suitable candidates also seem to be put off by the loss of privacy associated with the monitoring of SPAK judges (HJC 2020; European Commission 2021).

The majority of SPAK judges were recruited at the start of the SPAK Courts’ operations from among members of the former Serious Crime Courts (HJC 2019). During 2020, around ten full-time positions in the first instance and five full-time positions in the second instance were staffed (HJC 2020), which is about half the number required by law.e236c034721c When the number of judges in the SPAK Court of First Instance fell to five in April 2021 due to the departure of SPAK judges to the High Court, the first-instance court suspended the formation of different trial panels.

The staff shortages at the SPAK Courts have been met with an increase of special allowances and a campaign to raise awareness of the positions. To mitigate the problem, the High Judicial Council has extended a previously existing mechanism to the SPAK Courts that allows its bench to be supplemented with temporary judges, who are chosen by lot from among eligible candidates without requiring application (HJC 2020).9f9359c54fa5 However, temporary judges can only be assigned to specific cases in the event of the absence or legal unavailability (e.g., recusal) of a permanent judge. To date, the efforts do not seem to have significantly improved the situation.

Building an anti-corruption court amid profound reform: Prospects of the SPAK Courts

The establishment and operationalisation of the special structure form part of broader judicial reforms. The future prospects of the SPAK Courts are thus inherently linked to the trajectory of the overall reform.

While this linkage can result in challenges for the operation of the SPAK Courts, as demonstrated by the transitional re-evaluation process, the creation of a specialised court structure as part of comprehensive justice reforms also brings advantages. In contrast to other countries that have opted for more limited reform in setting up anti-corruption courts, there is no particular concern in Albania about the integrity of members of the superior instance, the High Court, as its judges have undergone the same vetting process. The same is true in principle for the integrity of SPAK prosecutors and investigators. In addition, the simultaneous initiation of multiple reform projects reduces the risk of the SPAK Courts crowding out other (possibly more decisive) components of justice reform.

The SPAK Courts only became operational in December 2019, and the reform process is continuing. Thus it is too early to make substantial assessments about their performance. However, it is worth mentioning that the SPAK Courts processed 20 first-instance corruption cases in 2020, involving 29 defendants, none of whom were found innocent. During the same period, the Special Prosecution Office submitted 53 corruption cases with around 100 defendants to trial. The SPAK Courts have seized assets of two former Constitutional Court judges and a former High Court judge, as well as a former prosecutor general. While SPAK has conducted criminal proceedings in several high-profile cases,b7e2ba970311 investigations so far have not resulted in a substantial number of final convictions of high-ranking state officials. The notable exception is the case of a former prosecutor general who was convicted and sentenced to a two-year prison term by the SPAK Court of Appeals, though his current whereabouts are unknown (SPAK 2020; European Commission 2021). Whether the SPAK Courts will be able to build on such initial achievements in the future also depends on the steady continuation of the judicial reform process that started with the profound transformation of Albania’s Constitution in 2016.

- The Croatian Office for the Suppression of Organised Crime and Corruption (USKOK) and the Romanian National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA) served as references.

- The two flagship initiatives are the EU’s Consolidation of the Justice System in Albania (EURALIUS) and the US Department of Justice’s Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance and Training (OPDAT).

- At various times, the Serious Crime Courts had jurisdiction over a broad range of offences such as narcotics offences, human trafficking, war crimes, kidnapping, and organised crime.

- See Laws 95/2016, 98/2016, and 7905.

- Including the president, speaker of the Assembly, prime minister, members of the Council of Ministers, judges of the Constitutional Court and High Court, prosecutor general, high justice inspector, mayors, deputy of the Assembly, deputy ministers, members of the High Judicial Council and High Prosecutorial Council, and heads of central or independent state institutions as defined by the Constitution or by law.

- The same amendment to the Criminal Code that introduced monetary thresholds for corruption cases (see below) centralised jurisdiction over all terrorism cases in the SPAK Courts.

- Three of these cases fell into the jurisdiction of the SPAK Courts because of the defendants’ identities, but they related to corruption at the same time. Sixteen cases with 113 defendants sent to trial concerned organised crime.

- ALL refers to Albanian leks. Dollar amounts are United States dollars.

- Law 96/2016.

- For the SPAK Court of First Instance, seven years of experience in office is required, five of which must have been in the field of criminal justice or in a specific position with responsibility for disciplinary proceedings. For the appellate instance an additional three years in office is required (Law 96/2016).

- Currently, only judges and prosecutors who have successfully passed the ‘transitional re-evaluation process’ (see below) are considered to have passed the security check. In the future, the security check is to be conducted by an internal committee of the special structure, consisting of two special prosecutors and one SPAK judge, selected by lot, as well as one employee of the financial investigation section of the Special Prosecution Office and one investigator of the National Bureau of Investigation, appointed by their superiors (Law 95/2016).

- Close family members are defined as spouses, children over 18 years old, and any person related by blood or marriage who lives for more than 120 days a year in the same residence (Law 95/2016).

- While other anti-corruption courts, such as the Croatian USKOK Courts, allow for security and financial checks on judges during their terms, no other country in the region has opted for such an extensive institutionalised monitoring as Albania.

- The legislation is not consistent on which information must be reported. One provision mentions information that gives rise to a reasonable suspicion of corruption, leaking of information, communication with criminal organisations, political influence, or any act that may violate the penal code. Elsewhere, the law refers to a reasonable suspicion of inappropriate activity. Ethical misconduct is also mentioned.

- The legislation is not entirely clear on this point. It also mentions six months.

- It is not clear whether these rules also apply to the monitoring of other forms of telecommunication.

- In Albania, constitutional amendments require a two-thirds majority in the Assembly and must be approved by popular referendum. Political factors can, of course, also present an obstacle to constitutional change.

- Only four of 19 High Court judges passed the vetting (Hoxhaj 2021).

- Law 95/2016.

- Law 98/2016.

- Temporary judges do not seem to be subject to the rules on monitoring of assets and telecommunication.

- Including a former prosecutor general, nine former High Court and Constitutional Court judges, a former judge of the Special Appeals Chamber, a deputy chief of the State Police’s Power of Law Operation, 20 election commissioners, and a former minister of defence.