Query

Please provide an overview of corruption in the Syrian Arab Republic.

Caveat

This Helpdesk Answer is based on a literature review that draws predominantly on English language sources, a significant portion of which express opposition to Assad’s administration.

Many authors outside of Syria refer to the Assad government as a “regime”, noting his administration’s autocratic structure, contested legitimacy and concentration of power in the hands of a narrow group of people often related to Assad (BTI 2023; Freedom House 2023; Heydemann 2023; Mehchy et al. 2020). However, in recent years, Assad’s government has been tentatively welcomed back into the fold by other Arab governments (Ioanes 2023; al Jazeera 2023).

This Helpdesk Answer generally employs the term “administration” or “government” when referring to state structures in areas controlled by Assad. Nonetheless, on occasion, this paper refers to the “Assad regime” as an analytical term to designate the narrow group of political actors around Bashar al-Assad that has captured core state institutions and who use this control to perpetrate crimes such as extortion or the illicit trafficking of arms, drugs and human beings.

Background

According to international observers, Syria is currently regarded as one of the most corrupt countries in the world (Transparency International 2024), with one of the most repressive governments in the world (BTI 2023; Freedom House 2023). To understand the nature of Bashar al-Assad’s government and the sources of its power, it is necessary to comprehend the specific political and economic context in which al-Assad came to power, as well as the rationale behind the power struggles between the presidency and the Ba’ath party in the first decade of his rule.

Bashar al-Assad succeeded his father Hafez in 2000, pledging reforms, including market liberalisation and the overhaul of established patronage networks (Laub 2023). During the three decades of Hafez al-Assad’s rule (1971-2000), his regime captured the state apparatus, utilising a network of cronyism, transforming state institutions into instruments of his rule (Khaddour 2015: 4; Perthes 1995). Hinnebusch (2015: 44) argues that the Ba’ath party played an important role in this process, serving as a tool for fostering ideological conformity as well as a patronage network, which erased the distinction between the political actors and the Syrian state.

After Hafez’s death, the national legislature approved a constitutional amendment that lowered the minimum age for president to 34, Bashar’s age at the time. He was then appointed secretary-general of the ruling Ba’ath party,9a284a4ea472 which nominated him as its candidate for the presidency. Running unopposed, he won his first seven-year presidential term.

In the initial period of his presidency, Assad pushed for certain reforms, such as a slight loosening of restrictions on freedom of expression and the press, and the release of several hundred political prisoners (Carnegie Middle East Centre 2012). This period, known as “Damascus Spring”, was characterised by relative openness, and there was optimism in some quarters that Bashar al-Assad would end his late father’s authoritarian practices (Carnegie Middle East Centre 2012).

Other significant shifts took place in the first years of Bashar al-Assad’s rule, including initiatives to privatise state monopolies (Moubayed 2008). Laub (2023) notes that, while these moves were intended to promote economic reform, the benefits of these processes were concentrated in the hands of politically connected actors. In addition, the ending of subsidies and price ceilings harmed peasants and workers (Laub 2023).

The education sector was also privatised, ending the period of state control imposed by the Ba’ath party in 1963 (Moubayed 2008). Yet other reforms to foster a more inclusive political landscape stalled. For instance, there were no attempts to amend the Article 8 of the Syrian constitution, which cemented the Ba’ath party’s role as ruling party of the state and society (Moubayed 2008).52fa9c6fe4c4

Nevertheless, in the first years of Bashar al-Assad’s presidency, the Ba’ath party developed into a rival source of power, competing with the president for control over the military, security forces and the government (Hinnebusch 2015). In this power struggle, Assad prevailed, largely succeeding in replacing the old guard with his loyalists by 2002 (Hinnebusch 2015). Although Assad was able to install loyalists into crucial positions, these new allies lacked extensive networks, contributing to the erosion of ties between his administration and its former rural support base (Hinnebusch 2015: 21).

This shift led to Assad’s increased reliance on new business elites who became wealthy during the economic reforms in the first decade of his rule (Hinnebusch 2015). For instance, his cousin Rami Makhlouf was one of the new tycoons who monopolised profitable economic sectors and seized opportunities that emerged during privatisation processes (Hinnebusch 2015: 39).

During the “Damascus Spring”, demands for political, legal and economic reforms became increasingly audible, and there was a growth in opposition activism, led by a number of Damascene intellectuals demanding political pluralism (Carnegie Middle East Centre 2012; The Syria Report 2001).

However, despite the initial openness, Assad’s presidency soon reverted to authoritarian measures in the second half of the 2000s (Hinnebusch 2015). This included an intensification of censorship, surveillance and violence against Assad’s opponents, particularly after Syria’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005 (Human Rights Watch 2010).

O’Donoghue (2020: 36) argues that this period marked a return to “rule by law”, in which the government’s “arbitrary power to create and refine law at will [was] a key feature”. This enabled Assad to establish a “relatively stable governance order” characterised “not [by] lawlessness but the absence of the rule of law”, whereby powerful figures were able instrumentalise existing laws and on occasion operate above them (O’Donoghue 2020: 36-37). In these conditions, Leenders (2010: 3) argues that the judiciary largely served as an instrument “of the regime’s coercive strategies to repress dissent”.

Civil war

While attempting to address the central weaknesses of his inherited administration, such as declining oil rents, Assad retained many aspects of his father’s regime, including its nationalist legitimacy (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015). Yet the declining rents were a significant driver of the 2011 popular uprising, because the cross-sectarian coalition built during Hafez al-Assad’s rule was heavily dependent on them (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015). As these rents faltered, the clientelist ties between political elites and the lower-middle and lower classes broke down (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015: 291).

The same period saw the emergence of tycoons who had profited from economic liberalisation (Hinnebusch 2015), resulting in growing inequalities in Syrian society (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015). For instance, agricultural liberalisation largely benefited investors who were able to take over former state land (Daher 2018).

By 2007, 33% of Syrians were living below the poverty line, more than double the poverty rate (14.3%) in the late 1990s (Abu-Ismail et al. 2011: 7; Matar 2015). Free trade agreements opened Syria to imports that undercut small and medium-sized domestic manufacturers, while the features of rule by law and corresponding absence of rule of law deterred investments in productive assets (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015: 292).

The situation was compounded by the fact that, between 2006-2010, Syria experienced its worst drought in modern history, leading to hundreds of thousands of farming families being impoverished (Richani 2016). This led to a mass migration of people to suburban areas, further contributing to already rising urban unemployment levels (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015).

Arguably, sectarian divisions also played their role, as the Sunni majority felt sidelined due to the privileges granted to Alawite elites, a minority sect of Shia Islam to which the Assad family belongs (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015).e3941402d234

The initial significant protests against the government took place in March 2011 in the rural province of Dar’a, which had been heavily affected by drought. The catalyst was the arrest and mistreatment of boys who had spray-painted anti-Assad messages on a school wall, leading to public demonstrations in support of them (Laub 2023). These protests quickly expanded beyond Dar’a to include major cities like Damascus, Hama and Homs (Laub 2023). President Assad’s response to the unrest included a national address where he attributed the turmoil to external influences aiming to destabilise Syria (Taub 2016). The government's response escalated as the Syrian army employed severe measures, including mass arrests and the use of lethal force against demonstrators. Reports of torture and extrajudicial killings in detention centres also emerged (Laub 2023).

In late April 2011, the Syrian army brought in tanks, laying siege to Dar’a, while residents were cut off from electricity, food, water and medicine (Hinnebusch and Zintl 2015). The situation in Syria rapidly evolved from widespread protests into a civil war, involving the Syrian government and opposition forces. This conflict has been marked by significant international involvement, with key powers such as Russia, Iran, the United States, France, the UK, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates playing substantial roles (Centre for Preventive Action 2024).

Already in July 2011, defectors from Assad’s army formed the Free Syrian Army (FSA). Other opposition coalitions followed, as will be discussed in the following sections (Laub 2023).

Today, more than 90% of the Syrian population live below the poverty line (Lederer 2023). According to World Bank figures, the pre-conflict population of more than 22.7 million slumped to 18.9 in 2016 before recovering to 22.1 in 2022 (World Bank 2023). In total, 11.9 million people have been forcibly displaced within Syria and across its borders (Kešeljević and Spruk 2023).

Areas of control

Over the 13 years of civil war in Syria, state actors and non-state armed groups have developed interdependent political economies in which boundaries between formal and informal have largely disappeared (Heydemann 2023). This is particularly evident in border areas, where close ties between smugglers, government officials, brokers, and armed groups have emerged (Heydemann 2023).

To secure legitimacy, ruling coalitions in areas held by both Assad and opposition groups have either captured or established formal institutions that provide basic social services, regulate local markets and oversee cross-border exchange (Heydemann 2023). They also manage the distribution of essential commodities and humanitarian aid, which is one important driver of corruption in Syria.

According to Heydemann (2023), in territories held by Assad, one can observe: i) the capture of state institutions and functions and their transformation into tools of “regime predation”; and ii) the expansion of the Assad administration’s involvement in illicit economic activities that constitute an important source of revenue. In the opposition held territories, predatory behaviour is also visible. Yet while in areas under Assad’s control, organised crime exerts an influence on the state, in areas controlled by other groups there are notable attempts by these non-state actors to transform themselves into governing authorities with institutions resembling those of fully fledged states (Heydemann 2023).

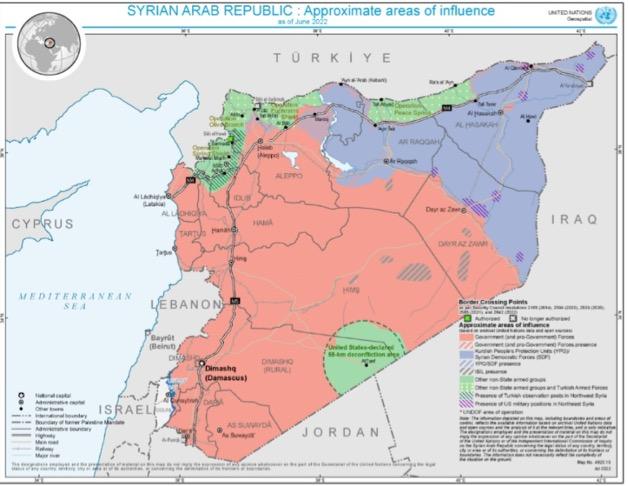

There are four distinct areas of control in Syria, that include:

- the Syrian authorities (under President Bashar al-Assad)

- the Syrian Interim Government (SIG)

- the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG)

- the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) (see Figure 1) (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023: 10-11)

Figure 1 on the next page shows the approximate areas of control in Syria: red designates the Syrian authorities, green with yellow dots is for the SIG, green is for the SSG, and purple is for the AANES. Source: Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2023: 11).

Syrian Arab Conflict: Approximate areas of influence

The Syrian authorities

The Syrian government maintains control over the majority of the country’s territory, as shown in Figure 1, with involvement at various points in time of a variety of foreign and domestic armed factions. These include the Russian military, the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), pro-Iranian militias, local self-defence groups and quasi-criminal gangs (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023: 11; see also Kourany and Myers 2016).

According to the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2023), these groups are active in government controlled areas, and there is evidence of the government delegating control to various factions within its territory, especially in the southern provinces of Daraa and Suweida. ISIS cells have also been reported in areas under government control (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023).

The government led by Assad uses state institutions to enhance its legitimacy and authority by providing essential goods and services to the population. However, reports suggest that these institutions are used to advance the interests of a select group close to Assad’s inner circle (Mehchy et al. 2020). The office of the presidency, the Ba’ath party and the security agencies are said to be key entities through which the clique around Assad exerts influence over state operations (Mehchy et al. 2020).

The Syrian Interim Government

In late 2012, the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces was established in Doha, comprising Syrian opposition groups, representatives of local councils, armed groups, the Kurdish National Council, the Assyrian Democratic Organisation (ADO) and other minorities (Hauch 2021: 2). The coalition had the objective of governing opposition held territory, uniting Syrian armed opposition under a military command and establishing a transitional government (Hauch 2021: 2). The coalition established the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) in 2013 as its temporary executive branch, consisting of nine ministries that were intended to oversee and provide support to local and provincial councils in the opposition held areas (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023; Hauch 2021: 2). The area under its control includes two pockets bordering Turkey: one from Afrîn in the west to Jarablus in the east, and the other from Tel Abyad to Ras al-Ayin (Tsurkov 2022).

Although SIG was initially welcomed with enthusiasm by western actors, its international support has waned over the years due to the lessening of western interest in the Syrian conflict, the eroding of the SIG’s legitimacy inside Syria and its close ties with Turkey (Hauch 2021: 1).

The Turkish backed Syrian National Army (SNA), a coalition of armed Syrian opposition groups was officially established in 2017. Although formally SNA answers to SIG’s Ministry of Defence (Tsurkov 2022: 5), in practice the SNA is under the control of Turkish military and intelligence (Tsurkov 2022). Moreover, SIG lacks control over appointments, resources and decision-making as Turkish governor’s offices across the border appoint and pay judges, policemen, teachers and doctors working for the SIG’s ministries (Tsurkov 2022: 12). Turkey also exhibits influence over local councils (Tsurkov 2022).

The Syrian Salvation Government

The Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) was formed in 2017 in Idlib province in the northwest, as an alternative government of the Syrian opposition (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023). It was backed by an Islamist rebel coalition Hay’at Tahrir a-Sham (HTS), which holds the de facto power in the area (Nassar et al. 2017; Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023; Nasr 2023). HTS grew out of Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda and was designated a terrorist organisation by the US, Turkey and United Nations (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023: 13; Nasr 2023; Tsurkov 2022). HTS operates in the greater Idlib area, which includes parts of Aleppo’s western countryside, the Lattakia mountains and al-Ghab Plain (Al Abdullah and Sallam 2023).

In this region, HTS and SSG have developed an elaborate institutional framework akin to that of fully fledged states, including presidents, cabinets, ministries, regulatory bodies, executive agencies and others (Heydemann 2023). SSG has a prime minister who is elected by a legislative body called the General Shura Council, and 11 ministries (Solomon 2022; Levant 24 2023).

The formation of SSG was one of the attempts of HTS to gain legitimacy among the local population, as SSG, composed of independent and HTS linked technocrats, serves as the governance wing of HTS (Al Abdullah and Sallam 2023). Through the SSG, HTS administers various welfare programmes, runs food aid programmes and controls the economy through al-Sham Bank (Al Abdullah and Sallam 2023). SSG also issues civil documentation for over 3 million civilians, two-thirds of whom are internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Al Abdullah and Sallam 2023). Moreover, HTS controls the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Turkey, through which humanitarian aid flows, upon which 90% of people living in northwest Syria depend (Al Abdullah and Sallam 2023).

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

The Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), a confederation of multi-ethnic political parties, associations, civil society organisations and local activists, was established in 2015 and serves as the political leadership of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) (The Syrian Democratic Council no date a). The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) acts as the military wing of the SDC and was able to take back control of vast swathes of land from ISIL with the backing of the US (Impact and East West Institute 2019; EUAA 2023). Following these territorial gains, the SDC decided to establish an autonomous administration for the north and east Syria, leading to the formation of AANES (Impact and East West Institute 2019; The Syrian Democratic Council no date b).

AANES does not have full control of its territory as several enclaves are controlled by the Syrian authorities, and troops of the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) and the Russian army are present on the border with Turkey (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2023: 14).

Extent of corruption

According to international observers, Syria is one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Corruption pervades all parts of society and is widespread in areas controlled by both the Assad government and opposition groups (BTI 2023; Freedom House 2023; Transparency International 2024). Residents of contested parts of the country are subject to abuse, combat sieges and interruptions of humanitarian aid, and mass displacement (Freedom House 2023).

Much of the Syrian economy is tightly controlled by the Assad government and its allies. The civil war created new opportunities for corruption, benefiting the Assad administration and its associates, including foreign allies, who, according to Freedom House (2023), benefit from opaque trade deals and government contracts. Additionally, humanitarian aid and basic state services are reportedly extended or withheld based on political loyalty to the Assad government (Freedom House 2023).

Freedom House (2023) reports that corruption is widespread in opposition held areas as well. For instance, militias backed by Turkey have been accused of looting, extortion and theft, while local activists complained that little international aid reportedly given abroad to opposition representatives reaches them, raising suspicions of graft (Freedom House 2023).

The Bertelsman Transformation Index (BTI) (2023) report states that corruption in Syria is endemic, with all governing administrations reliant on illicit sources of revenue. Corruption cases against high-level officials or powerful business entities are typically related to internal power struggles rather than genuine anti-corruption efforts (BTI 2023).

The Organised Crime Index (2023) notes that criminal actors, encompassing state-embedded players, foreign entities and criminal networks, engage in different forms of corruption, such as bribery and nepotism, to exert control over criminal markets, such as drug production and trafficking.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) (2024) places Syria almost at the bottom of the list, with the country ranking 177 out of 180, with a 2023 score of 13 out of 100.

Survey evidence suggests an increase in the perception of corruption. One study identified in 2020 found that 54% of respondents answered that there are very high rates of corruption (SACD 2021a). Moreover, over half of respondents said that they would not report corruption (SACD 2021a). The same study found that more than half of respondents (52%) thinks that they do not have a fair and transparent access to the judicial system (SACD 2021a: 39).

Forms of corruption

State capture

Since 2011, the civil war in Syria has reshaped the dynamics of political and business interactions in the country. A 2019 meeting at the Sheraton hotel in Damascus, convened by the governor of the Central Bank of Syria, exemplifies changes in the composition of the business elite closely connected to the Assad government (Jalabi 2023a). At this gathering, prominent business figures were asked to deposit US dollars into the Central Bank in an attempt to stabilise the Syrian currency (Jalabi 2023a). Halabi (2019) notes that this group of businessmen included individuals virtually unknown before the outbreak of the civil war, and who had amassed significant wealth through their dealings in the war economy. This new class of business elite that has emerged since 2011 now dominates key economic sectors and maintains strong ties to the Assad government (Halabi 2019).

Indeed, political connections to the Assad faction have become essential for business success, as these ties provide access to operating checkpoints, obtaining real estate on expropriated land and the illicit trade in oil (Mehchy et al. 2020; Jalabi 2023a; Hinnebusch 2020).

Mehchy et al (2020: 7) observe that the Assad government’s proclivity to govern through rule by law has deepened during the civil war. They note that the presidency simply issues laws and directs parliament to approve them, so that the “sole determining factor in the implementation of these laws […] is the regime’s interests in retaining power and controlling Syria’s resources”. According to the authors, Assad and his associates use state institutions to extract rents from businesses, harassing them through seizures, extortion and expropriation (Mehchy et al. 2020).

Indeed, the rule by law and passage of new legal provisions has underpinned systematic asset seizures directed at businesses and helped Assad get a firm grip on the Syrian economy and create a new business elite loyal to and dependent on the clique around Assad (The Syria Report 2022). The highest profile victim of this process was Bashar’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf, who reportedly controlled over half of Syria’s economy before the war (Jalabi 2023a). In 2020, the Syrian government ordered the seizure of Makhlouf’s assets and imposed a five-year ban on his ability to contract with public entities (Al Jazeera 2020; Bulos 2020).

State capture is also associated with tailor-made laws. These laws benefit not only domestic politically connected business entities but also foreign companies tied to Assad’s allies, such as Russia and Iran. In 2018, Law No. 10 was passed, enabling the creation of redevelopment zones for reconstruction, the true purposes of which, Mehchy et al. (2020: 9) allege, was to redistribute properties and land to politically connected profiteers. Some firms enjoy special agreements with government entities. According to Mehchy et al. (2020: 14), a prominent example is HESCO Engineering & Construction Company, which imported crude oil and whose owner has a personal relationship with Assad and strong ties with security agencies, as well as good relations with Russian companies.

Other arrangements involve laws that legalise the monopoly position of certain firms. For instance, Legislative Decree No. 19 passed in 2015 allowed local councils to establish holding companies in partnership with private firms. Mehchy et al. (2020: 14) report that, based on this decree, entities with links to US-sanctioned tycoons have been established and successfully monopolised all reconstruction projects overseen by the Assad government. According to the US Department of the Treasury (2019), these joint ventures have seized property owned by Syrian citizens and transferred it to government insiders in exchange for a share of the profits.

Other government decisions benefit those close to Assad’s inner circle, such as the requirement from 2019 onwards for all households in Damascus to use a smart card to purchase fuel. A company called Takamol was granted exclusive rights to manage and organise the smart cards, and this company was reportedly partially owned by a cousin of Bashar al-Assad’s wife Asma (Mehchy et al. 2020; Open Sanctions no date).

Jalabi (2023a) identifies Asma as a key figure in the dynamics of state capture after 2011. Serving as the leader of the president’s economic council, she reportedly leverages this position to establish wide-ranging patronage networks and manage the distribution of international aid funds in areas under government control (Jalabi 2023a). Additionally, Jalabi (2023a) contends that the Assad government has taken control of the extensive charity and patronage network previously managed by Rami Makhlouf, thereby strengthening its hold on the aid sector.

Yet other laws benefited foreign interests. For instance, Law No. 5 passed in 2016 allowed foreign investors to become shareholders in public entities. This law provided a legal framework for the economic exploitation of Syria’s assets, such as the Russian investment in the port of Tartous (Mehchy et al. 2020: 7). Further, Sabbagh et al. (2022) report that a large mobile operator in Syria, Wafa Telecom, which received a licence in 2022 as well as a three-year monopoly to run the country’s first 5G network, has multiple ties with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, while one of its key shareholders is Assad’s aide, Yasar Ibrahim.

State capture is evident in the opposition controlled areas as well. Although these areas are not fully fledged states, they do have parallel institutions that are firmly under the control of armed groups. According to Mehchy et al. (2020: 17), there is both formal and informal cooperation between the de facto authorities and affiliate economic entities.

For instance, the dominance of HTS in Idlib has been used to establish control over lucrative enterprises (Mehchy et al. 2020). Watad Petroleum, for instance, has been granted monopoly rights over the fuel market in Idlib (Haid 2019; Mehchy et al. 2020: 17). Moreover, Watad Petroleum has been able to secure a reduced tariff on the transportation of fuel that was imposed at the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Turkey. This reduction, however, did not lead to a noticeable reduction in prices in Idlib, but it has reportedly only benefited Watad Petroleum at the expense of local governance entities (Mehchy et al. 2020: 18).

While lucrative contracts to operate oil wells in the northeast (the area controlled by AANES) are nominally offered through public tenders, in practice, the winners are chosen on the basis of political connections (Mehchy et al. 2020: 17).

Administrative corruption

Bribery is reportedly one of the most common forms of corruption in Syria, driven in large part by poor economic conditions, low wages, and the government's lack of action in countering corruption (COAR 2022a: 6). However, it is worth noting that bribery was widespread even before 2011, serving as a means to navigate the state’s bureaucracy.

Coercive bribery is particularly widespread in state institutions, including in the education and health sectors, as bureaucrats reportedly consider it a vital portion of their income (COAR 2022a: 6). This disproportionately affects the poorer segments of the population and those without political connections (COAR 2022a: 6). One study found that 59% of respondents answered that they need to pay bribes to obtain their citizenship rights, such as acquiring documents or securing government permissions (SACD 2021a).

Demands for bribery extend beyond basic public services as citizens are sometimes forced to pay bribes to avoid detention or harassment by the security services (COAR 2022a). Checkpoints are another means of extorting bribes. For instance, in 2016, the National Union of Syrian Students erected checkpoints at the entrance of Al-Ba’ath university in Homs to extract payments from students (COAR 2022a: 7). These forms of abuse typically go unchecked due to strong ties between student unions and the security apparatus (COAR 2022a: 7).

Additionally, COAR reported that citizens had to pay bribes to brokers to book appointments through the new portal for passport applications, which came online in 2021, with bribes reportedly ranging between US$40 and US$318 (US Department of State 2022; COAR 2022b).

Corruption in opposition held areas is reportedly widespread in quasi-formal institutions and service provision entities (Mehchy et al. 2020). In the northwest, Awad (2021) reports that local councils give a percentage of the aid they receive to officials from the General Administration of the Displaced Affairs who are affiliated with SSG in order to influence the allocation of supplies to IDP camps in their area. Therefore, humanitarian aid is also affected by bribery.

In the northeast, some local organisations are incentivised to bribe officials to ensure timely registration (COAR 2022a). Furthermore, there is evidence of widespread corruption within the self administration. For instance, the fuel committee in Deir ez-Zor has reportedly abused its authority over fuel allocation by conditioning subsidies on receiving bribes from recipients (Mehchy et al. 2020: 22).

Drivers of corruption

Conflict and sanctions

Conflict has further weakened the capacity of state institutions in Syria, which were already suffering from inefficiency and a lack of accountability. This can be attributed to several factors, including exhausted financial and human resources, weak law enforcement and poor monitoring systems (Mehchy et al. 2020). For instance, one study found that the civil war led to unprecedented deterioration in institutional quality, resulting in the erosion of the rule of law and an escalation of corruption (Kešeljević and Spruk 2022; Even and Fadlon 2021).

Conflict in Syria has created new opportunities for corruption, particularly due to a high influx of humanitarian aid and the proliferation of humanitarian aid organisations. The Assad government reportedly relies on profiteers and intermediaries to evade sanctions while importing goods (US Department of the Treasury 2019). Profiteers are known to set up shell companies that enable them to trade and conduct financial transactions (Mehchy et al. 2020). Sanctioned individuals manage to evade sanctions using different tactics, such as creating complex offshore networks, obscuring the ultimate beneficial owner (COAR 2022a: 14).

In the opposition controlled areas, profiteers take advantage of the lack of capacity of quasi-formal institutions (Mehchy et al. 2020: 20). Profiteers include businesspeople, corrupt officials, intermediaries and pre-conflict associates of the Assad government (Mehchy et al. 2020: 5). Conflict related activities, including smuggling, kidnapping, drugs and weapons trading, confiscating property and monopolising local markets, are widespread in areas controlled by Assad and opposition groups (Mehchy et al. 2020: 5). Political and military leaders often appoint their relatives to manage economic activities in the territories they control (Tsurkov 2022: 14).

The conflict has created incentives for ruthless short-term profit maximisation, which can lead to infighting between different factions in opposition controlled areas. For instance, in the area controlled by SIG and SNA, these conflicts are driven by competition over resources, such as controlling checkpoints where taxes can be extorted, controlling smuggling routes into areas held by the Assad government, Iranian-backed militias, the SDF, and across the border with Turkey (Tsurkov 2022: 11). Those who win these internal struggles gain access to corrupt profit-generating schemes.

Protection rackets imposed by armed groups are another source of revenue. For instance, SNA extorts money from businesses, farmers and traders operating in the areas of their control (Tsurkov 2022). The two types of protection rackets in the SNA controlled areas include protection of specific business premises (e.g. shops and factories) and the protection of trucks carrying goods (Tsurkov 2022: 15).

As the conflict resulted in the displacement of inhabitants of the region now controlled by the SNA, it was followed by looting of movable and immovable property. Immovable property, in particular, became a lucrative source of funding for factions, as some buildings were distributed to fighters in the factions who rented them out (Tsurkov 2022: 17).

All these sources of profit generated in the war economy enabled army commanders to amass huge wealth that they further invested by setting up businesses in regions they control (Tsurkov 2022). These businesses also serve as a source of patronage as commanders are thought to employ fighters in their businesses for additional wages (Tsurkov 2022).

Illicit trade and smuggling

There is some suggestion that economic sanctions have led to increased corruption in Syria, due to their impact in increasing the price of even basic goods (Sakr-Tierney 2023; Ljubas 2024). The Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust (2021) argues that by forcing Syrians to look to the black market, sanctions have fuelled corruption and organised crime.

Ten years of conflict, rampant unemployment and poverty have certainly contributed to the expansion in the trade of scarce and illicit goods, for which Syria is both a source and a destination country.

Trade in weapons, oil and tobacco smuggling, and sales of the illegal amphetamine Captagon have been documented (Jalabi 2023a, 2023b; Global Organised Crime Index 2023). The Assad regime has relied on illicit networks to expand its reach into private markets such as crude oil imports and spare parts for oil wells (Mehchy et al. 2020).

Similar practices exist in opposition controlled areas. For instance, northern Aleppo is at the crossroads of several trade and smuggling routes, connecting Turkey with the rest of Syria, from which goods are exported and then traded to areas held by the SDF and the Assad government (Tsurkov 2022: 14). Due to differing prices of basic goods (e.g. diesel, gold, sugar and cars) between different areas of control, smuggling is an ongoing practice (Tsurkov 2022).

The illicit-arms market in Syria is one of the largest in the world and implicates both domestic and foreign actors with ties to the Assad regime (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). Arms trafficking also happens in Kurdish affiliated areas of Al-Hasakah, Raqqa and Deir-ez-Zor and in southern Syria. Arms primarily arrive from neighbouring countries (Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan), while some are stolen from Syrian army stores or sold by corrupt state officials, ending up on the black market (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). Reportedly, there has been a surge of Iranian made weapons trafficked into Syria, allegedly intended for the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and militias supported by Iran in the region (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

Drug trafficking is another pressing and growing issue in Syria. The smuggling of Captagon pills from the areas held by Assad is facilitated through a network of warlords and profiteers (Jalabi 2023b).

An investigation by France 24 (2022) suggests that Assad’s brother Maher, the de facto head of notorious 4th division of the Syrian army, is heavily involved in the smuggling of Captagon. Two of Assad’s cousins have been sanctioned by the US and UK for their alleged role in the manufacture and export of Captagon pills (Jalabi 2023b). In a statement announcing the sanctions, the British government noted that the drug trade is a financial lifeline for Assad’s regime, enriching his inner circle at the expense of the Syrian population (Jalabi 2023b).

Drug smuggling is also present in the opposition held areas. Namely, Captagon pills, manufactured in areas held by Assad or in Lebanon, cross the SNA controlled areas into Turkey, from where they are shipped to Gulf states (Tsurkov 2022). These smuggling networks are transnational, and involve Syrians, Lebanese and Saudis, but many key players in the network have tribal ties that reach beyond national borders (France 24 2022). According to estimates based on available data, this is a multi-billion dollars industry (France 24 2022). SNA also recently more aggressively moved into the Captagon business, and France 24 (2022) reports that Abu Walid Ezza, a commander of the Sultan Murad faction of the SNA, emerged as a kingpin in the region.

Likewise, the illicit oil trade involves collusion between opposition forces and the figures associated with the Assad government. For instance, intermediaries involved in transporting crude oil from oil fields in the northeast to the state-owned Homs refinery reportedly include a member of parliament, Houssam Katerji, who has been sanctioned by the US as a war profiteer (Mehchy et al. 2020: 16; Halabi 2019).

Georgy and El Dahan (2017) state that, together with his brother, Baraa, Katerji facilitated the purchase of wheat from areas under ISIS control, while other reports indicate the brothers have helped the Assad government evade sanctions to import oil (Mehchy et al. 2020: 16; US Department of the Treasury 2019).

The illicit trade in goods is also widespread in Syria. For instance, smuggling networks of tobacco products extend beyond the country’s borders, and Syria has in recent years emerged as a destination for the tobacco smuggled from Lebanon, Iran and United Arab Emirates (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). Reportedly, these illicit activities are facilitated by foreign forces in the country and state-embedded actors and are a significant revenue source for smuggling networks along the borders as well as a source of bribes for government officials and arms groups that control borders and checkpoints (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

Human trafficking in Syria is among the most egregious in the world as the country is the major source and destination country for forced labour and sexual exploitation targeting both local and foreign victims (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). Children are exploited by state and non-state actors and used as combatants, human shields and suicide bombers (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). There is a lucrative market with regards to organ trade (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). Human smuggling typically occurs along the borders with Turkey, Lebanon and Iraq, allegedly facilitated by actors close to the state (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

Further, people are also smuggled through the SNA controlled areas as many wish to reach Turkey, and high-ranking SNA commanders are, according to Tsurkov (2022: 14), involved in the smuggling of refugees into Turkey. In the northwest, HTS has broad control over the networks smuggling people into Turkey, and it charges a fee for regulating and permitting these illicit activities (Mehchy et al. 2020: 18; Shami 2022). In recent years, human smuggling also occurred between Syria and Cyprus on fishing or rubber boats (Spring and Al Halabi 2023). This smuggling is facilitated by corruption as smugglers reportedly have good ties with high-level security officers, including military security department and navy officers, who enable them to organise boat trips to Cyprus in exchange for bribes (Spring and Al Halabi 2023).

The lack of reliable banking systems and volatile exchange markets

Corruption in financial transactions, both within and between different areas of control in Syria, is another pressing challenge driven by the lack of a reliable banking system and volatile exchange markets.

This issue has become particularly prominent in recent years, following the rapid depreciation of the Syrian pound (SYP) and the inclusion of the Central Bank of Syria (CBS) on the specially designated nationals and blocked persons list in 2020 by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) (COAR 2022a: 11; OFAC 2020). In July 2023, the Syrian currency reached its lowest level on the black market, trading at over 11,000 SYP to US$1 (Al Jazeera 2023).

These conditions render the Syrian currency susceptible to arbitrage and speculation, leading to an increase in unofficial and unlicensed transactions (Mehchy 2019). While the CBS attempted to curb speculation by introducing stricter regulations and currency valuations on banks, money transfer agents (MTAs) and traders, it is unable to enforce these regulations in the opposition held areas in the northeast and northwest (COAR 2022a: 11). Moreover, both licensed and unlicensed MTAs engage in transactions on the black market, sometimes in collaboration with security officials (COAR 2022a: 11).

Another challenge, associated with international aid, is the difficulty in tracking and overseeing the movement of aid dollars once they enter the Syrian financial system, due to a lack of transparency and checks and balances with regards to the movement of funds (COAR 2022a). This increases the risk of aid dollars being exploited by human rights violators and sanctioned individuals because humanitarian organisations struggle to monitor the movement of funds after they are exchanged inside Syria (COAR 2022a: 11-12). According to the CBS regulations, private banks can sell their dollars for commercial and non-commercial purposes, meaning that in theory they could be used for financing wheat imports or an arms deal (COAR 2022a: 12).

Reports suggest that the Syrian government makes international aid agencies use a distorted exchange rate set by the CBS, which is significantly lower than the one determined by supply and demand as reflected on the black market (Hall et al. 2021). In 2020, this reportedly enabled the Assad government to divert close to 51 cents of every dollar of international aid spent in the country (Hall et al. 2021). For UN agencies alone, this equated to around US$60 million being diverted (Hall et al. (2021). One recent study found that, as of August 2022, the UN operational exchange rate was 2,800 SYP to US$1, while the black market USD rate was around 4,200 SYP to US$1 (COAR 2022c: 5). COAR (2022a: 12) claims that it is common for staff at private and public banks, including high-level officials, to use dollars for off-the-books transactions, making illicit profits in this way (COAR 2022a: 12)

Main sectors and areas affected by corruption

International aid

Due to the conflict that began in 2011, Syria has become one of the largest recipients of humanitarian aid in the world, with the bulk of this spending facilitated by the United Nations (UN). Besides being the major provider of humanitarian aid in Syria, the UN has exercised influence over the distribution of around US$2.5 billion per year since 2014 (SLDP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022: 8).

Reported instances of corruption affecting humanitarian aid organisations include accusations of corrupt hiring practices and mismanagement of funding (USAID 2016; Parker 2018; Kayyali 2019; Sabbagh and Al Ibrahim 2022; SACD 2021b; Hall et al. 2021). For instance, the Associated Press reported that World Health Organisation (WHO) staffers told investigators that the agency’s Syria representatives pressured WHO staff to sign contracts with high-ranking government officials and misspent WHO and donor funds (Cheng 2022).

One major issue concerning humanitarian aid procurement is that international aid organisations often have few options other than to work with politically connected businesses involved in import, transport or security when moving goods and money into the country (COAR 2022a: 9).

Evidence of corruption in international aid in territory controlled by the Syrian authorities (under President Bashar al-Assad)

A lack of oversight and accountability in aid distribution in government controlled areas in Syria has created opportunities for aid distribution to be captured and diverted at all levels (Betare and Ghosh-Siminoff 2022). According to a recent study, 85% of NGO/CSO respondents said that Syrian government security services interfere in the distribution of humanitarian aid.

The biggest beneficiaries of aid diversion are reportedly the intelligence services and the army, but other actors involved include businessmen, and political elites close to Assad, as well as the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) and local NGOs receiving aid (Betare and Ghosh-Siminoff 2022: 6; Kayyali 2019). Another study based on a survey of 45 employees from 29 different aid organisations in areas controlled by Assad’s government found that over 80% of interviewees confirmed that the Syrian authorities interfere in their organisation’s work, typically through determining who is eligible to receive support from these organisations, appointing directors, managers and employees, as well as diverting resources away from intended beneficiaries to military and security agencies (SACD 2021b).

In fact, the Syrian government has developed a policy and a legal framework that facilitates the diversion of aid, according to a Human Rights Watch report (2019). This framework consists of government imposed restrictions on the access of humanitarian organisations to communities in need of aid, selective approval of humanitarian projects, and the requirement to partner with security-vetted local actors. These practices enable the diversion of humanitarian aid to the benefit of the state apparatus at the expense of the population in need (Kayyali 2019: 2).

Aid diversion is endemic at all levels, starting with the moment when the UN procures its aid in Lebanon to the point of delivery (Betare and Ghosh-Siminoff 2022: 6). Evidence suggests that the Syrian government has distorted the humanitarian aid system to supply the needs of the army, militias and security services, as NGOs have reportedly been ordered multiple times to send food, tents and clothes to Syrian army soldiers (Betare and Ghosh-Siminoff 2022: 7). The Syrian government allegedly uses monitoring and evaluation firms to justify the aid diversion, by providing false reports, and these firms are linked to Bashar al-Asad and his wife Asma (Betare and Ghosh-Siminoff 2022: 7).

A recent study of UN procurement contracts, investigating the top 100 private and public-private suppliers in Syria in 2019 and 2020, found that almost half of procurement funding (47%) in the analysed period has been awarded to risky or high-risk suppliers (SLDP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022; Zaman 2022). One example is Desert Falcon Llc, a company co-owned by Fadi Saqr, who is reported to have close ties with Assad and is the leader of the National Defence Forces militia in Damascus (SLDP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022: 4). This study identified seven key issues with the current UN procurement processes in Syria that directly result from the failure of the UN’s agencies vetting process (SLDP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022: 4):

- human rights abusers taking advantage of the system

- contracting individuals and entities sanctioned for human rights abuses

- failing to identify front entities and intermediaries

- reliance on large contracts

- lack of transparency

- accommodating corruption

- the failure to protect staff

For instance, the reliance on large contracts effectively limits competition, as only large firms have capacity to deliver a contract, and they are more likely than the smaller firms to be politically connected to the Assad regime. This study also documents evidence of a lack of transparency, as the name of the supplier was withheld for security or privacy reasons for US$75 million worth of procurements in the period studied (SLDP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022: 20).

Further, corrupt practices in UN procurement processes are reported to include taking bribes from businesses to rate them favourably or providing insider information to bidders to help them win tenders (SLDP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022: 22). In addition, studies suggest that many UN agencies in Syria are forced to hire family members of senior intelligence officers (Betare and Ghosh-Siminoff 2022: 8).

Evidence of corruption in international aid in territory controlled by other factions

Humanitarian aid reaching opposition held areas faces significant challenges from the outset. Humanitarian operations require the permission of the government in place to access territories, and the Syrian government has consistently withheld permission for access to opposition held areas, preventing critical support from reaching these areas (Kayyali 2023). As a consequence, in 2014, the UN Security Council passed a resolution that allowed aid to enter Syria without government approval and authorised four border crossings for aid delivery (two in the northwest, one in the northeast and one in the southwest) (Kayyali 2023).

In the northwest, the SSG has been accused of stealing humanitarian aid and appointing corrupt staff in the administration of camps under their control (Shami 2020).

In 2016, the US government suspended millions of dollars in funding to several organisations providing aid to Syria from Turkey after discovering that they were overpaying Turkish companies with the collusion of some of their staff (The New Arab 2016; Siemrod and Parker 2016). According to the US Agency for International Development, a network of commercial suppliers and NGO employees were engaged in bid-rigging, bribery and kickback schemes in relation to contracts for the delivery of humanitarian aid to Syria (The New Arab 2016).

Public procurement

Corruption in public procurement processes in Syria – particularly procurement involving the delivery of humanitarian aid – extends beyond the country’s borders and implicates both domestic and foreign actors, including political officeholders, domestic tycoons, foreign oligarchs, individuals in international organisations and NGOs.

Evidence of corruption in public procurement in territory controlled by the Syrian authorities (under President Bashar al-Assad)

Public procurement processes are instrumentalised in areas controlled by Assad to serve the interests of government officials and connected businesses at the expense of public interest (Mehchy et al. 2020: 2). Public contracting is used to ensure loyalty by limiting competition and helping a class of businessmen get immensely rich (COAR 2022: 9). For example, Hamsho, a company in the ownership of former MP Muhammad Hamsho, reportedly secured 591 contracts with the Ministry of Education between 2016 and 2018 (Mehchy et al. 2020: 15). According to Mehchy et al. (2020: 15), it was later revealed that these contracts were a cover for corrupt transactions that cost the state budget around US$200 million. The Assad government later confiscated Hamsho’s assets and forced him to repay the government for the misappropriated funds (Mehchy et al. 2020: 15). While the reason behind the businessman’s apparent fall from grace in this instance is unclear, other cases suggest that nominal anti-corruption enforcement actions related to public procurement contracts are used as a pretext to target businessmen who become too powerful or fall out of Assad’s favour (COAR 2022).

Corruption in public procurement is also visible in the healthcare sector. Evidence suggests that public tenders for medical equipment and medicines provide opportunities to public officials for collusion with businesses in invoicing the government at much higher prices than the companies pay to actually provide such services (Mehchy et al. 2020: 19).

Corruption in public procurement contracts has also benefited Assad’s foreign allies, Russia and Iran. For example, a Russian firm Stroytransgaz Engineering, which had reported links to Putin’s associate Gennady Timchenko, won contracts for three largest phosphate facilities in Syria (COAR 2022: 9). This deal is said to have enriched sanctioned oligarchs, war profiteers and the Syrian government (Bassiki et al. 2022).

Evidence of corruption in public procurement in territory controlled by other factions

Similar practices of collusion between the de facto authorities and affiliated businesses exist in the opposition held areas.

In the northeast, where a significant part of the local councils’ activities are outsourced to private firms, Mehchy et al. (2020) report that tenders are rarely publicly announced and instead shared with politically connected individuals. As these contracts are conditional upon obtaining security clearance, bribes or a share of future revenue are often provided to security to get approval (Mehchy et al. 2020: 17-18). For instance, Mehchy et al. (2020) state that the Al-Sheikh Construction Company based in Deir ez-Zor has capitalised on personal ties to the members of the governorate’s councils to win a substantial share of contracts (Mehchy et al. 2020).

Security sector

The security sector landscape in Syria has undergone significant changes since the onset of the conflict. International interventions by Russia, Iran and non-state actors in support of the Assad government in Syria have undermined the central command structures of the Syrian armed forces (Batrawi 2020). In addition, the creation of pro-Assad militias has led to the establishment of armed groups beyond the control of the Syrian armed forces (Batrawi 2020). This diversification of armed structures has arguably resulted in the establishment of localised power centres and the empowerment of warlords (BTI 2022).

Evidence of corruption in the security sector in territory controlled by the Syrian authorities (under President Bashar al-Assad)

According to Batrawi (2020: 12), three key dynamics within the Syrian armed forces are corruption, profiteering and sectarianism. With the deteriorating economic conditions in Syria over the years following the start of the conflict, the predation by Syrian army soldiers, militiamen and secret police increased (Tsurkov 2021). Batrawi (2020: 12) argues that corruption in the armed forces is condoned by the Assad regime to retain the personal loyalty of its troops despite low salaries.

The smuggling business is an important source of revenue for the Assad’s armed forces. The British government has claimed that Assad’s brother Maher, who commands the 4th division of the Syrian army, is involved in facilitating the production and distribution of multi-billion dollar shipments of Captagon (UK Government 2023). Beyond drugs, the 4th division oversees a network of trafficking and cross-border smuggling, providing protection to traders (Aldassouky 2020; Tsurkov 2021). The number of checkpoints that extort money from people has also been used by armed forces to supplement their income (Tsurkov 2021).

Evidence of corruption in the security sector in territory controlled by other factions

In the opposition held areas, armed groups, such as the SNA in the northwest, also resort to corruption, manifesting in (Tsurkov 2022):

- extortion of money from businesses, farmers and traders that operate in areas under their control

- people smuggling

- securing monopoly on smuggling of various goods, and profiting on the difference in prices between different territories

- profiting from dispossession (looting of movable and immovable property)

Some evidence points to organised corruption in the areas under the control of SIG and SNA, in northwest Syria. According to some witnesses, bribery of and connections to the military police in these areas are used to secure the release of high-value prisoners of war (Al Nofal 2022a).

In 2022, the US backed commander of Maghawir al-Thawra factiondb9dfd27ec90 was replaced due to internal disagreements and allegations of corruption and involvement in drug trafficking (Al Nofal 2022b).

Further, HTS, through the General Authority of Zakat, forces farmers to pay levies and taxes on wheat, under the pretext of collecting “crops Zakat” money (Syrians for Truth and Justice 2023). These levies were first imposed in 2019, and again in July 2023. HTS deployed checkpoints in areas under its control in Idlib to force farmers to pay (Syrians for Truth and Justice 2023).

Justice sector

The justice sector in Syria is deeply corrupt, politicised and controlled by local authorities (Global Organised Crime Index 2023). In areas controlled by Assad’s forces, officials in the judiciary are required to be members of the ruling Ba’ath party and the president can dismiss judges at a whim through presidential decree (Global Organised Crime Index 2023).

Evidence of corruption in the justice sector in territory controlled by the Syrian authorities (under President Bashar al-Assad)

The war has created new opportunities for corruption in the justice system. According to the US Department of State (2022), human rights lawyers and family members of detainees, officials in courts and prisons solicit bribes for favourable decisions. Widespread detention is linked to systematic forms of corruption at the level of both state capture and administrative corruption.

A report by the Association of Detainees and the Missing in Sednaya Prison (ADMSP) (2022: 32) claims that the Assad regime has instrumentalised the court system to confiscate assets worth huge sums of money from detainees since 2011, including cash, property, businesses, jewellery and livestock. The fact that such confiscations are often legal underscores the extent of “rule by law” in the country.

In addition, families of arbitrarily detained or forcibly disappeared persons seeking information about their loved ones are frequently confronted by exploitative networks demanding bribes (US Department of State 2022). Based on the findings of another survey, ADMSP (2021: 44) estimates that corrupt officials have collected the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars since 2011 by extorting bribes from family members of detainees in exchange for information about their loved ones or promises of visitation or release. The report identifies a network of actors involved in this process, including guards, judges, members of the military and in some cases middlemen who receive a cut from this extortion scheme (Surtees 2021; ADMSP 2021).

Judges reportedly take bribes to release those accused of smuggling (Tsurkov 2021). The NGO Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) reported that, accordingly to lawyers they spoke to, it costs between US$1,194 and US$3,184 to bribe a judge to sign a release order for a detainee (US Department of State 2022).

There is evidence of corrupt networks using courts to strip exiled or émigré Syrians of their property. In the absence of centralised court records, one lawyer discovered 125 cases of stolen homes in Damascus in the first half of 2022 (Ahmed et al. 2023). Networks engaged in the process of taking over property reportedly have up to 50 complicit members, involving lawyers, judges, military officials and other actors (Ahmed et al. 2023). They engage in finding empty homes, forging sale documents and pushing them through the courts without the knowledge of the owners (Ahmed et al. 2023).

Evidence of corruption in the justice sector in territory controlled by other factions

There is evidence of corruption in the justice sector in areas controlled by the SSG and HTS. For example, individuals receive preferential treatment in the judicial system based on their social status or affiliation with HTS (Mehchy et al. 2020: 22).

Further, there is evidence indicating widespread corruption in courts affiliated with HTS, manifesting in the acquittal of people accused of serious crimes in exchange for monetary bribes (Awad 2020).

Health sector

Even before the war, public healthcare in Syria was in poor condition. The conflict has exacerbated long-standing issues in the health sector, such as corruption, profiteering, loyalty based appointments and geographic disparities in the quality of care (Tsurkov and Jukhadar 2020).

Attacks on healthcare facilities have been widespread since the start of the conflict, which has further negatively contributed to the availability of healthcare throughout the country. Physicians for Human Rights (PHS) documented 583 attacks on health facilities from the onset of the conflict and until 2019, of which more than 90% were conducted by the Syrian government and its allies (Koteiche et al. 2019).

Evidence of corruption in the health sector in territory controlled by the Syrian authorities (under President Bashar al-Assad)

Corruption is widespread in the public health facilities. For instance, networks of medical and administrative staff illegally sell subsidised medicine to the private health sector, resulting in reduced quality of the public health services (Mehchy et al. 2020: 21). Corruption allegations have also been levelled against the head of the World Health Organisation in Syria (Cheng 2022).

Despite sporadic attempts to counter corruption, such as the dismissal of key figures in public hospitals in 2018 under the guise of an anti-corruption campaign, corrupt practices persist, arguably because the system that facilitates corruption has not changed (Mehchy et al. 2020).

Consequently, there is widespread impunity for corruption among state officials, leading to incidents such as the theft of medical supplies from state hospitals by staff and demands on patients to pay for medical examinations to which they are entitled (Tsurkov and Jukhadar 2020; Enab Baladi 2020).

Reportedly, following the recapture of areas by Assad’s troops, health services in those territories have rarely been restored, and care in government hospitals depends on favouritism and connections (Tsurkov and Jukhadar 2020).

Evidence of corruption in the health sector in territory controlled by other factions

The control of the health sector in opposition held areas lies with local de facto authorities. In the northwest, SSG Ministry of Health controls Idlib Medical School and health facilities in Idlib city and other areas within its control (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 5). The Idlib health directorate is independent of any government and is in charge of overseeing hospitals across the opposition controlled area (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 5). In the Turkish controlled areas in the north, the Turkish government oversees healthcare, supported by the SIG Ministry of Health in rural areas (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 5). In the northeast, the AANES Ministry of Health oversees the health sector by using health committees in each region under its control (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 5).

Due to humanitarian aid not meeting the population's needs, some aid, such as surgical equipment, is smuggled into northern Syria through crossings with Turkey and Iraq (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 12). Bribes are reportedly paid to facilitate this smuggling (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 12).

Northeast Syria is almost fully dependent on aid transported by land from the Bab al-Hawa crossing in the northwest through Idlib and the areas controlled by Turkey. Health facilities in this region must account for transportation costs and bribes to various actors, which can triple the price of medication (Physicians for Human Rights 2021: 10).

Other stakeholders

Media

In government controlled areas, media workers are subject to censorship, detention, torture and death in custody. Private media owners tend to be politically connected (Freedom House 2023). According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF) (2024), Syria ranks 175/180 countries, and media are instrumentalised by the Assad government to promote Ba’athist ideology, while any form of pluralism is excluded.

There are some independent and opposition media, of which many are based abroad, such as Enab Baladi and Syria Direct.

Civil society

According to Freedom House (2023), the Assad government tends to deny registration to NGOs with human rights and reformist missions, and they are subject to harassment, intimidation, raids and violence.

There are some initiatives, such as Madaniya initiative (al-Abdeh and Hauch 2023), which had its inaugural conference in Paris in 2023, gathering over 180 participating organisations (al-Abdeh and Hauch 2023).

Other non-profit organisations include, for example:

The Association of Detainees and The Missing in Sednaya Prison

- For further details about Ba’ath party and its origins, see Hinnebusch (2015).

- Article 8 was removed following the start of 2011 popular uprising. Assad appointed a committee in November 2011 to draft a new constitution, which was approved in 2012. The new constitution deleted this provision and introduced a multiparty system (Fares 2014). In practice, however, control remained concentrated in Assad’s hands, as Article 105 of the constitution appointed the president as the commander-in-chief of the army. The president also controls the four intelligence agencies (Fares 2014).

- Detailed discussion on this topic goes beyond the scope of this Helpdesk Answer, and there are different views in the literature on the role of sectarian divisions in the Syrian conflict. See, for example: Aldoughli 2021.

- This faction operates in a 55 kilometer area of the south-eastern Syrian desert, where the US led international coalition maintains a presence in the al-Tanf military base in this zone (Al Nofal 2022b).