Corruption is a threat to development. Yet global corruption trends have remained unchanged for over a decade, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2022.d7a43df02d74 Development cooperation is also responding to an increasingly complex policy environment driven by the geopolitical contest between global powers, the deterioration of global peace and security, COVID-19 pandemic recovery efforts, and the climate crisis. At the same time, we are at the midpoint of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, whose Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16.5 calls on countries to ‘substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms’.

The U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (U4) is investing in understanding sector-based anti-corruption approaches to inform effective solutions.4fb1f786425d The mainstreaming or integration of anti-corruption into sector programmes has been an ongoing objective of U4’s development partners since 2004.07ef11a6d866 A U4-commissioned study in 2013 found that anti-corruption mainstreaming efforts were most common in development cooperation in the health, education, and natural resource management sectors.b81003703803 Less frequent has been the integration of anti-corruption approaches into justice sector assistance.5ba5efc7ee31

The justice sector occupies a unique place in the fight against corruption because it can be part of the problem as well as part of the solution.a8bf11464aa6 The justice sector plays a central role in a state’s governance structure as a check on political and elite power. A well-functioning justice sector is a tool for curbing many forms of corruption, from political corruption and grand corruption to administrative and petty corruption, with potential for impact across the whole of society. Yet when corruption occurs in justice institutions, formal or informal, it erodes public trust and undermines the sector’s capacity to combat impunity.

An evaluation by the European Commission of a decade of European Union (EU) rule of law assistance highlights the disparity between the high level of support provided to the justice sector and the lower level of support to anti-corruption efforts.6e337748e6b0 From 2010 to 2021, the rule of law sector received the largest share of EU funding support, while anti-corruption interventions received the least.0d5ac4c0d027 The EU was ‘much less visible and successful in fighting against corruption, because it lacked clear policies, guidance, capacity, expertise and incentives to address this sensitive issue in an integrated and context-specific manner’.9931b6bf5ec1 Moreover, a recent guide by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) highlights that ‘sectoral programs have often treated corruption as either a political or democratic hurdle to be overcome, or as a contextual challenge to be identified, though not squarely addressed’.32b1a169f71e There is a need for deeper anti-corruption expertise to support sectoral programming, particularly in justice sector assistance.

This U4 Issue seeks to inform development cooperation efforts to support the fight against corruption in and through the justice sector. We present the findings of a mapping of justice sector assistance supported by U4’s eight partners, the ministries of foreign affairs or development agencies of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Together these U4 partners make up a quarter of the members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), an international forum of the largest providers of official development assistance (ODA).3d52ff9c2911 Half of the U4 partners are also members of the EU.86e74ab2f894

The main questions guiding our study were as follows. We were able to address some questions in more detail than others:

- What initiatives and programmes are U4 partners currently supporting or planning to support in the justice sector, and what is their mode of delivery?

- Do U4 partners take political context into account in project design?

- What theories of change inform the anti-corruption interventions, how are these theories developed, and to what degree are they evidence-based?

- How do these interventions address corruption directly or indirectly?

- Are there any good practices that partners consider worth highlighting?

- What are (intervention-specific) obstacles in addressing corruption directly or indirectly in justice sector and rule of law programming?

- What evidence of effectiveness, grounded in evaluations, is available?

- Do U4 partners and other donors collaborate on these interventions? In what way?

We encountered two principal challenges in our research effort. One was the difficulty of identifying justice sector assistance that contains anti-corruption elements. This was due to, among other factors, the lack of a dedicated anti-corruption policy objective marker within the reporting requirements of the OECD DAC Credit Reporting System (CRS), the common reporting framework used by U4 partners. The other main challenge was the practice by development partners of ‘doing anti-corruption without naming it’. This made it difficult to determine whether interventions are in fact addressing corruption, since some may be addressing it without making that explicit.

Our recommendations aim to support development partners and practitioners in efforts to further integrate anti-corruption strategies into justice sector assistance. The findings and policy implications contained in this U4 Issue continue the conversation begun in our previous publications on this topic: Mapping evidence gaps in anti-corruption: Assessing the state of the operationally relevant evidence on donors’ actions and approaches to reducing corruption(2012); Mainstreaming anti-corruption into sectors: Practices in U4 partner agencies (2014); and Mapping anti-corruption tools in the judicial sector(2016).

Study methodology

Desk review

We reviewed primary and secondary literature to contextualise our understanding of current policy considerations for justice sector and anti-corruption assistance. Our desk review took place throughout the study period, from November 2022 to October 2023.

Mapping of U4 partners’ justice sector assistance

We collected data on justice sector assistance actively being provided or earmarked to be provided by U4 partners as of May 2023. The U4 partners are Global Affairs Canada (GAC); Denmark’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA Denmark); Finland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA Finland); Germany’s Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ); Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad); Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC); and United Kingdom (UK) Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). We collected data through two methods: (a) by submitting a survey to U4 partners, and (b) by scanning U4 partners’ online project databases. This data collection took place in the period from December 2022 to May 2023.

Data collection

In December 2022 we sent out a survey to half of the partners –MoFA Finland, MoFA Denmark, Sida, and Norad – asking them to list their justice sector assistance and to specify whether interventions were addressing corruption, directly or indirectly. Only MoFA Finland completed the survey, while Sida and MoFA Denmark submitted internal project lists to us. We created a project list for Norad using data available in Norad’s online project database. For the other partners, GAC, UK/FCDO, GIZ, and SDC, we anticipated that each would have dozens of projects, so we did not send a survey. Instead, we created preliminary project lists based these partners’ online project databases and sent the project lists to the partners for validation in December 2022; not all partners completely validated the project list.

Although our initial goal was to have partners self-identify interventions with anti-corruption approaches, only Finland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs provided this information. For all other partners we ultimately made the assessment ourselves, based on open-source data, and validated our analysis with the partners. We reviewed logical frameworks, descriptions of project goals, objectives, and intended results, as well as press releases and media reporting, where available, for each project.

Defining the justice sector

We defined the justice sector broadly and counted all interventions that engaged with a justice institution, actor, or process. Justice institutions included courts and administrative tribunals, public prosecution offices, public defenders, legal aid providers, law enforcement and security sector agencies, detention facilities and prisons, as well as law schools, bar associations, and civil society organisations working on justice issues. We also considered actors such as judges, court administrators, prosecutors, lawyers, and legal academics, as well as civil society actors working on justice issues. We further counted justice processes such as access to justice, transitional justice, and community dispute resolution. We did not count an anti-corruption intervention unless there was a nexus to a justice sector institution, actor, or process.

Since the focus of our study is how U4 partners address corruption through justice sector assistance, we considered the dual role of the justice sector and counted (a) interventions that seek to address corruption in the justice sector, and (b) interventions that enable the justice sector to address corruption in other sectors. We further considered anti-corruption assurances within partners’ justice sector assistance, where the information was available, although that was not the primary consideration of our study and we did not comprehensively map this information.

Direct and indirect anti-corruption measures

We assessed an intervention as having a direct anti-corruption approach or measure if project documents explicitly referred to addressing corruption.

We assessed an intervention as having an indirect anti-corruption approach or measure if project documents included approaches that could contribute to addressing corruption, such as by promoting good governance, transparency and accountability, integrity, oversight, access to information, monitoring and reporting, and related measures. Although not stating an explicit anti-corruption objective, these approaches have the potential to prevent, mitigate, and reduce corruption by improving governance.

Case studies of anti-corruption approaches

We selected one project from each of seven partners to study in depth, grouping them into six case studies (Table 1).154adaab08eb In our case study selection, we sought to capture a representation of different justice institutions and actors and diverse geographic regions. The selection was not intended to reflect an evaluation or endorsement of any intervention’s value or effectiveness, but sought to highlight different anti-corruption approaches in justice sector assistance.

We conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 12 key informants, comprising anti-corruption focal points at U4 partners, project leads, implementing partners, and project beneficiaries, during April–May 2023.

Table 1: Case studies of justice sector assistance supported by U4 partners

|

U4 partner |

Country of implementation |

Project title |

Project description |

|

GIZ and UK/FCDO |

Bangladesh |

Justice and Prison Reform for Promoting Human Rights and Preventing Corruption (2008–2023) / Access to Justice through Paralegal and Restorative Justice Services in Bangladesh (2013–2023) |

The project aims to improve access to justice for the poor by reducing the inflow of cases into the judicial system, reducing the remand population in prisons, and increasing diversion of cases out of the formal criminal justice system. The project is funded by UK/FCDO and implemented by GIZ. |

|

MoFA Finland |

Kyrgyz Republic |

Strengthening Human Rights Protection and Equal Access to Justice in the Kyrgyz Republic – Phase 3 (2022–2024) |

The project aims to sustain access to justice and to quality legal aid services, in particular for women, people living in rural areas, and people with disabilities; to strengthen inclusive public access to legal information and oversight mechanisms for promoting and monitoring legal empowerment and the effective implementation of justice and human rights standards at national level; and to advance the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. |

|

SDC |

Egypt |

Support the Juvenile Justice System in Egypt (2020–2025) |

The project promotes a more independent, impartial, and efficient judiciary as a prerequisite for the protection of citizens. The project engages the juvenile justice system, recognising it as one arena where there is both a demonstrated need for reform and government acceptance of international development assistance. Capitalising on the OECD framework agreement with Egypt on rule of law, the intervention aims to enhance sector-specific governance practices and contribute to increasing trust with government stakeholders. |

|

Norad |

Global |

Corruption Hunter Network |

The project sustains a network of practitioners committed to combatting corruption. Participants in the network come from 15–20 countries and include prosecutors and heads of anti-corruption agencies, along with special invited persons from academia, media, and civil society. The network has met regularly since 2004. |

|

Sida |

Moldova |

Supporting the e‑Transformation of Policing Processes Related to Contravention Cases (2022–2026) |

The project aims to ensure that offences in Moldova are registered using digital means, thereby diminishing human error/interference and opportunities for corruption. It also seeks to ensure that the investigation of offences is undertaken by police in a timely manner and with full accountability. |

|

GAC |

Honduras |

Justice, Governance, and Fight Against Impunity in Honduras (2018–2023) |

The project supports the promotion of human rights in Honduras by increasing the access to justice of vulnerable populations, especially women. This is done by training and accompanying lawyers and civil society organisations to actively participate in legal and democratic processes that help reduce impunity and improve the rule of law in Honduras. |

Source: Table created by the authors based on survey results and mapping of each of the U4 partners’ online project databases from December 2022 to May 2023.

Results of mapping and case studies

Justice sector assistance is a cross-cutting line of effort

Of the 174 justice sector interventions mapped, GAC and GIZ are supporting the highest number, with 44 and 43 interventions respectively. Next are SDC and Sida, with 20 and 19 interventions, followed by UK/FCDO and Norad, with 17 and 16 interventions. MoFA Finland is supporting eight interventions and MoFA Denmark is supporting seven. With respect to Germany, our mapping includes only GIZ interventions and thus does not represent all assistance provided by the Government of Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Likewise, for the other countries, we have only mapped assistance provided by the named agency or institution, which may not reflect all assistance provided by the government of each country. Table 2 lists the number of justice interventions we were able to map as of May 2023.227c7e284cd0

Table 2: Number of justice sector interventions supported by U4 partners

|

Partner |

No. of justice sector interventions mapped |

|

GAC |

44 |

|

GIZ |

43 |

|

SDC |

20 |

|

Sida |

19 |

|

UK/FCDO |

17 |

|

Norad |

16 |

|

MoFA Finland |

8 |

|

MoFA Denmark |

7 |

Source: Table created by the authors based on survey results, mapping of U4 partners’ online project databases from December 2022 to May 2023, and U4 partners’ OECD development cooperation profiles.

Our summary is based on the number of individual interventions per partner agency and does not fully reflect the level of assistance that each agency provides. Notably, each intervention supported by UK/FCDO is significantly larger in terms of the level of funding and duration of implementation than any of the interventions by other partners.523e600b3b41

Development cooperation by OECD DAC members is generally categorised into sectors according to the CRS purpose codes.4957003f20e4 Mapped interventions fell under a wide range of purpose sectors, as shown in Table 3.

A third of the interventions fall under CRS purpose code 15130, legal and judicial development (31% of interventions).9ed4a724027f Other top sectors include purpose codes 15180, ending violence against women and girls (9%)1ee1a25c3d69; 15160, human rights (6%)9b14dcb56694; 15150, democratic participation and civil society (6%)e475e79247d2; and 15220, civilian peace-building, conflict prevention and resolution (6%).7987eea97ef0 In a significant number of interventions (15%), we could not identify the assigned DAC purpose codes due to a lack of open-source information.e7d9c5d0e3c2

Table 3: Type and number of interventions based on OECD DAC CRS purpose codes

|

OCED DAC Purpose Codes |

Category name |

Number |

|

15130 |

Legal and judicial development |

53 |

|

|

Unknown |

26 |

|

15180 |

Ending violence against women and girls |

16 |

|

15150 |

Democratic participation and civil society |

11 |

|

15160 |

Human rights |

11 |

|

15220 |

Civilian peace-building, conflict prevention and resolution |

10 |

|

15113 |

Anti-corruption organisations and institutions |

8 |

|

15210 |

Security system management and reform |

7 |

|

15170 |

Women's equality organisations and institutions |

6 |

|

15134 |

Judicial affairs |

4 |

|

15131 |

Justice, law and order policy, planning and administration |

4 |

|

15110 |

Public sector policy and administrative management |

4 |

|

13010 |

Population policy and administrative management |

3 |

|

15112 |

Decentralisation and support to subnational government |

2 |

|

15132 |

Police |

2 |

|

15190 |

Faciliation of orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility |

1 |

|

15152 |

Legislatures and political parties |

1 |

|

72010 |

Material relief assistance and services |

1 |

|

43010 |

Multisector aid |

1 |

|

15137 |

Prisons |

1 |

|

16010 |

Social protection |

1 |

|

11330 |

Vocational training |

1 |

Notably, few interventions fall under CRS purpose codes 15134, judicial affairs (2% of interventions); 15132, police (1%); and 15137, prisons (1%). While this may indicate a comparatively low level of support to these institutions, we found that many interventions supporting the courts, police, and prisons are categorised under other DAC purpose codes, including 15130, legal and judicial development; 15180, ending violence against women and girls; and 15160, human rights. Therefore, the DAC purpose code assignments do not readily give an understanding of the type of justice institution, actors, or process targeted by a given intervention, and a closer review of project documentation is necessary.

The diverse range of DAC CRS purpose code sectors targeted by U4 partners’ justice sector assistance reflects the cross-cutting nature of justice sector support. For example, as shown in Table 4, only SDC states that advancing the rule of law is a primary objective of its development assistance. For other partners, support to the justice sector falls under efforts to promote inclusive governance (GAC), rights and civic space (MoFA Denmark), and peace and democracy (MoFA Finland, GIZ, and SDC).4d0d6e272d14

Table 4: Partners’ development cooperation priorities as stated in OECD DAC profiles.

|

Partner |

Development cooperation priorities |

|

GAC |

Gender equality; human dignity (health and nutrition, education, gender-responsive humanitarian action); growth that works for everyone; environment and climate action; inclusive governance; peace and security. |

|

GIZ |

Peace; food security; sustainable economy; climate, energy, and environmental protection; health and social security. |

|

SDC |

Creating decent local jobs; addressing climate change; reducing the causes of forced and irregular migration. Promoting the rule of law, building on SDC’s extensive multilateral and humanitarian experience. |

|

Sida |

Ukraine; humanitarian support; democracy; climate action; gender equality; trade; migration. |

|

UK/FCDO |

Supporting sustainable growth; women and girls; humanitarian assistance; climate change, nature, and global health. |

|

Norad |

Food security; climate; health; inequality; sexual and reproductive rights. |

|

MoFA Finland |

Rights and status of women and girls; sustainable economies and decent work; quality education; peace and democracy; climate change and sustainable use of natural resources. |

|

MoFA Denmark |

Climate change; supporting fragile and conflict-affected states and regions; promoting rights and civic space. |

The intersection of justice sector support with other sectoral programming has implications for anti-corruption mainstreaming, as it may give rise to competition for strategic focus, expertise, and resources. In the authors’ experience, where there are competing priorities, fighting corruption may receive less attention, particularly in contexts where there is no government support for anti-corruption efforts or where anti-corruption has become politicised by the government or ruling regime for a narrow purpose. Moreover, each strategic objective in a project design requires activity development, stakeholder buy-in, co-implementation partnerships, expertise, and resourcing, among other support. Multi-thematic expertise can be difficult to come by, particularly in the justice sector, given the high level of specialisation among practitioners such as lawyers, prosecutors, and judges. These considerations, among others, may limit anti-corruption integration where interventions are multi-sector or multi-thematic.

NGOs and the UN implement half of U4 partners’ justice sector assistance

While development cooperation by Germany is mostly implemented directly by GIZ, other countries in the mapping fund external partners to implement their interventions. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are the most common implementers, delivering a third of the interventions in the mapping.c54620fa8065

The next most common delivery method is through United Nations (UN) agencies, which are implementing 17% of mapped interventions.d40d8d9837e5 The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is the predominant partner among the UN agencies in this regard, implementing 18 of the 30 UN-implemented interventions. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is implementing six interventions; the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), four interventions; and UN Women, two interventions. Also included in the mapping are the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Table 5 depicts the different types of partners implementing U4 partners’ justice sector assistance.

Table 5: Implementers of U4 partners’ justice sector assistance, by category

|

Partner type |

Number of interventions |

|

Non-governmental organisations |

55 |

|

No partner/directly implementing |

45 |

|

UN |

30 |

|

Multiple types |

12 |

|

Intergovernmental organisations |

11 |

|

National governmental entities |

6 |

|

Unknown |

6 |

|

Academic institutions |

4 |

|

Other donors |

2 |

|

Anonymous |

1 |

|

Membership associations |

1 |

|

Private companies |

1 |

Other implementing partners include intergovernmental organisations, national government entities, academic institutions, private companies, and membership associations. There are two projects where UK/FCDO is funding GIZ as the implementer, reflecting collaboration between U4 partners: Access to Justice through Paralegal and Restorative Justice Services in Bangladesh (2013–2023) and Tackling Serious and Organised Crime in Ghana (2021–2026).

Less than half of justice sector interventions address corruption

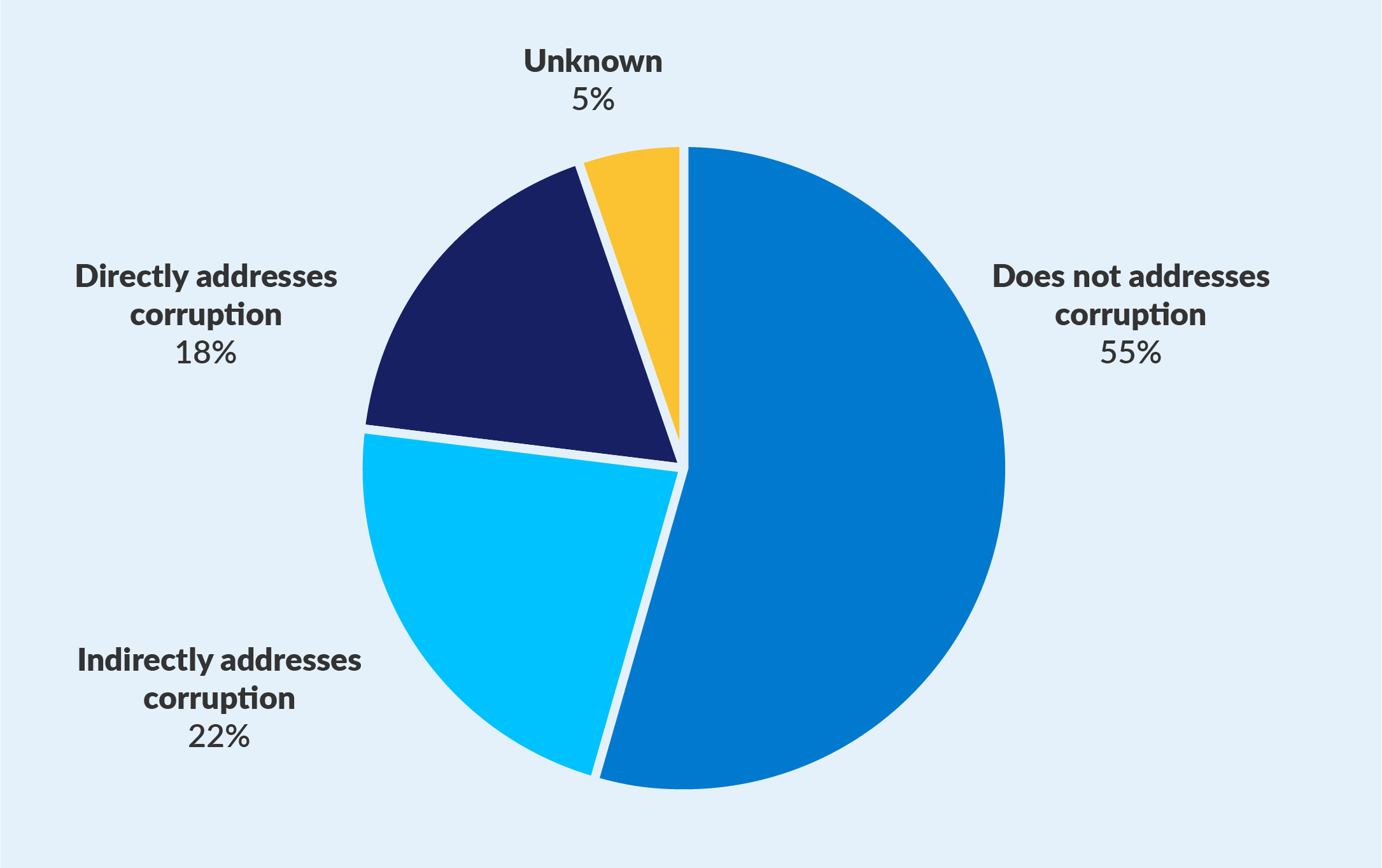

Figure 1 shows the percentages of mapped interventions with direct, indirect, and or no anti-corruption approaches. MoFA Finland is the only respondent that completed a survey on the presence of anti-corruption approaches in their justice sector interventions. For the remaining partners, we made the assessments based on open-source information. Without a DAC CRS policy marker for anti-corruption, it is not readily possible for U4 partners to generate an aggregate list of sector-specific assistance with anti-corruption objectives. A detailed list for each partner is included in the Annex.

Figure 1: Percentage of mapped interventions addressing corruption

Of the 174 interventions mapped, we found that 18% (31 interventions) addressed corruption directly. An example of an intervention that does so is the UK/FCDO-funded project Building Sustainable Anti-Corruption Action in Tanzania (2017–2025).The project seeks to improve the capacity and coordination of the criminal justice system in handling corruption cases.40d785907a66

Among U4 partners, MoFA Denmark has the highest percentage of its interventions directly addressing corruption, with 43% of interventions (3 of 7). Next are UK/FCDO and SDC, with 41% (7 of 17) and 40% (8 of 20) of their interventions, respectively, explicitly stating an anti-corruption approach. Around 18% (3 of 16) of Norad’s interventions are addressing corruption. The remaining partners incorporate direct anti-corruption approaches in less than 15% of their interventions, and Canada in only 2%.14524be0f85e

We evaluated about 22% of interventions (39) as taking an indirect anti-corruption approach.d47166804252 Indirect approaches can potentially address corruption even though their measures are not explicitly or solely linked to anti-corruption. Such measures may include, for example, efforts to improve case management systems, digitalise institutional processes, monitor lawmakers, and increase public access to legal information, along with other types of actions to promote transparency and accountability, good governance, integrity, and ethical standards.

MoFA Finland uses indirect anti-corruption approaches in 50% of its interventions, followed by the UK/FCDO (35%) and Sida (26%). Norad, SDC, and GIZ use indirect anti-corruption measures in 20%–25% of their interventions, while GAC uses them in only 16%. We did not identify any indirect anti-corruption approaches in MoFA Denmark’s seven interventions.3c8a0fc2acbc If these indirect approaches are considered, many more justice sector interventions are integrating anti-corruption without explicitly saying so.

There may also be more examples of indirect approaches that we were not able to identify and capture, and the anti-corruption integration rate for each partner therefore could be higher than these figures indicate. Anecdotal evidence and past research suggest that the practice of ‘doing anti-corruption without naming it’, thus avoiding the anti-corruption label, may be common among U4 partners.0f2e05db3883 There is growing evidence that indirect approaches to addressing corruption may be preferred and more effective than direct anti-corruption approaches. According to Jackson, countries that ‘have sustainably transitioned to a less-corrupt equilibrium have done so mostly without recourse to specific anti-corruption policies and institutions’. Instead, they have reduced corruption through ‘deeper changes to governance or society that often allow for broad and collective progress’.8f398f8e9de7

We estimate that around 55% of interventions (95) do not include any anti-corruption approach, whether direct or indirect.5674c21b1590 This result may suggest a low rate of anti-corruption mainstreaming in U4 partners’ justice sector assistance unless there are many interventions indirectly addressing corruption that we were not able to identify. For 5% of mapped interventions, we did not have sufficient open-source information to decide whether an anti-corruption approach is present, so we marked the results as unknown.

The apparently low rate of anti-corruption integration could be driven by several dynamics, including political sensitivities in contexts of weak governance as well as donor and host country priorities for development cooperation (Table 3). Interventions supporting state institutions – especially those functionally related to corruption, such as public prosecutors’ offices or financial intelligence units – tend to have more obvious anti-corruption objectives. UK/FCDO and SDC, in particular, tend to support such interventions. Interventions supporting civil society organisations to provide legal aid, promote human rights, and combat gender-bias norms may have less obvious anti-corruption objectives; many of these projects are supported by GAC.

The mandates and strategic priorities of implementing partners, particularly multilateral partners, may also contribute to the low level of direct anti-corruption efforts. In discussing a project implemented by UNDP, a representative of that agency stated that UNDP generally focuses on ‘corruption prevention’, while UNODC focuses on ‘combatting corruption’.f6b60bf9f125 We understand this to refer to a tacit difference in mandate between the two agencies following the adoption of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) in 2005. UNODC is mandated to address corruption directly, whereas UNDP is expected to implement measures that indirectly address corruption through its justice and governance programming. According to a 2008 UNDP report, a memorandum of understanding between UNDP and UNODC states that UNODC ‘has both the normative and technical assistance functions in relation to UNCAC’, while UNDP serves as ‘the coordinating arm of the UN and has a wider presence at the country level to promote human development’.855e9818785b In our mapping, UNODC is implementing six projects, with three projects addressing corruption directly and one project addressing corruption indirectly. In comparison, UNDP is implementing 18 projects, three of which address corruption directly and five of which address corruption indirectly. Since UNDP implements a higher number of mapped justice sector projects than does UNODC, and since UNDP is more likely to support indirect anti-corruption approaches, this may explain the higher number of indirect anti-corruption measures in our mapping.

Interventions are responding to corruption risks in the implementing context

The extent to which interventions explicitly address corruption may also be related to the level of corruption risk, measured in terms of risk perception, in the implementing context. Justice programming in contexts where corruption risk is high may be more likely to address corruption explicitly than programming in medium- to low-risk contexts.

U4 partners are supporting interventions in countries where the public perceives corruption risks to be high (Table 6). Based on Transparency International’s CPI in 2022, the ten countries with the highest perception of corruption risks in our mapping are Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Haiti, Sudan, Honduras, Iraq, Central African Republic (CAR), Tajikistan, Bangladesh, and Mozambique. We found that most programmes implemented in these countries are addressing corruption either directly or indirectly. The exceptions are DRC, Honduras, and CAR, which may warrant more anti-corruption assistance given the high perception of corruption risks and the comparatively low number of justice sector interventions integrating anti-corruption.

Table 6: Number of interventions addressing corruption in countries with the highest corruption risk

|

CPI ranking |

Country |

No. of interventions |

Addressing corruption? |

|

178 |

Somalia |

2 |

2 of 2 interventions address corruption indirectly |

|

169 |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

3 |

1 of 3 interventions addresses corruption directly |

|

164 |

Haiti |

1 |

1 of 1 intervention addresses corruption directly |

|

164 |

Sudan |

1 |

1 of 1 intervention addresses corruption indirectly |

|

157 |

Honduras |

7 |

1 of 7 interventions addresses corruption directly; 2 of 7 interventions address corruption indirectly |

|

157 |

Iraq |

1 |

1 of 1 intervention addresses corruption indirectly |

|

154 |

CAR |

1 |

No intervention (0 of 1) addresses corruption |

|

150 |

Tajikistan |

2 |

1 of 2 interventions addresses corruption indirectly |

|

147 |

Bangladesh |

3

|

2 of 3 interventions address corruption indirectly

Note: one intervention is funded by both UK/FCDO and GIZ and is counted as two separate interventions |

|

147 |

Mozambique |

2 |

1 of 2 interventions addresses corruption directly |

Source: Table created by the authors based on results of survey and data collection from U4 partners’ project databases from December 2022 to May 2023.

Anti-corruption in justice sector assistance: Three examples

In this section we highlight three anti-corruption approaches applied in justice sector assistance supported by U4 partners. Our review is not an evaluation or an endorsement of effectiveness, but aims to illustrate the types of approaches or measures currently being implemented.

An approach to addressing corruption indirectly is the digitalisation of case management systems to improve institutional efficiency and enhance transparency in justice service delivery. With support from Sida, UNDP is implementing a project in Moldova called Supporting the e‑Transformation of Policing Processes Related to Contravention Cases (2022–2026). By working to digitalise police case management of contravention cases, the project aims to diminish human error/interference and opportunities for corruption, and to ensure that the investigation of offences is done in due time and with full accountability by the police.

Another approach is the integration of human rights and anti-corruption programming to combat impunity. With support from GAC, Avocats Sans Frontières Canada (ASFC) is implementing Justice, Governance, and Fight Against Impunity in Honduras (2018–2023). The project works to show the human rights impacts of corruption and to define how individuals are victims of corruption and human rights violations, enabling legal redress to combat impunity.

Sustained support over time to increase networking among anti-corruption actors can strengthen the investigation and prosecution of grand corruption. The long-running Corruption Hunter Network (2009–present), facilitated by Norad, supports a global network of dedicated anti-corruption investigators and prosecutors. For over 17 years the network has provided anti-corruption actors with moral support, shared experience, contacts, and cross-border cooperation, enabling practitioners to investigate and prosecute high-profile grand corruption.

These three approaches and sample projects are described below in more detail.

Digitalisation of police case management in Moldova

Digitalising the procedures of public institutions can reduce unchecked discretion, increase transparency, and enable accountability, which in turn can have downstream effects in preventing corruption.da3dc612f3c2 In the justice system, digitalisation can enhance transparency and accountability in case management systems by limiting human error and interference and making information more readily accessible.

In Moldova, the government is pursuing the digitalisation of public services to promote a positive business environment, economic growth, and good governance.fdc7efbd97ba A former Soviet republic with an estimated 3.4 million people, Moldova is ranked 91 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s CPI in 2022, a mid-tier ranking.95ca6a8f628a The risk of encountering corruption when engaging with the police in Moldova has been assessed as very high.c2220554bbbe Tackling corruption is a top-level reform priority as the Moldovan government pursues membership in the EU, a policy imperative that is driving broader governance reforms. Digitalisation of the state’s ‘justice chain’ is already underway, with the courts and prosecutors’ offices undergoing e‑transformation of their processes in the past decade. Police are among the last institutions in the justice chain to digitalise.a6bc3e8efe1e

With funding support from Sida, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Moldova and UNDP are conducting the project called Supporting the e‑Transformation of Policing Processes Related to Contravention Cases (2022–2026).d9bee139f1da The project helps prevent corruption by increasing transparency and accountability in the management of contravention cases.be8c6d2dbde6 According to UNDP’s project lead, digital transformation ‘brings clarity for police and citizens’.1791c58d1c40 There are around 600,000 contravention cases annually, representing 85% of police documentation activity in Moldova. UNDP is supporting the Ministry to develop an automated information system that will increase connectivity among the 44 institutions and agencies mandated to investigate contravention offences. The system will ensure secure access to data, with only the agent in charge of each case able to manage the case file. Supervisors will be able to view the file but will not have editing permission. Integration of the e‑contravention system with e-services offered by the Moldova e‑Governance Agency will ensure interoperability with other platforms and databases and enhance overall transparency of public services.cee95667403d According to UNDP’s project lead, the intervention seeks to change the ‘business model of the police’ to bring ‘more trackability of police officers’.dab424cb192f By enabling digital oversight of the case work of individual police officers and enabling public access to electronic information, digitalisation of policing case management can act to deter and control corruption.

To implement the project, UNDP is drawing on lessons learned from the Moldovan judiciary’s e‑transformation, an experience that is viewed as largely successful due to sustained support from USAID over the course of ten years. According to the UNDP representative interviewed for this study, a lesson learned from this period is the importance of generating support for digital reform among middle managers within Moldova’s public institutions. The UNDP representative anticipates resistance from mid-level and line police officers as ‘they have the most burden to take on with the digital reform’. In response, UNDP plans to adapt its efforts to address this potential resistance to reform.7a46a92745c8

It is too early to know the impact of the project. Researchers are gathering evidence to show that across settings, at the macro level, digitalisation can reduce corruption.94c72b78da5e These experts note that integrity is not usually the primary driver and anti-corruption is not the top objective of government digital reform, but the reforms nonetheless may have positive effects in preventing corruption. This may be the case for the UNDP project, which has the potential to help curb corruption by increasing transparency and accountability in case management, although the primary goal of the project is to enhance the efficiency of policing in Moldova.

Integrating human rights and anti-corruption in Honduras

It has been over a decade since the International Council on Human Rights Policy and Transparency International issued a seminal report calling for the integration of human rights and anti-corruption programming around the shared principles of participation, transparency, and accountability.2cf17817f095 The nexus between the rule of law, human rights, and corruption is now well recognised. Corruption erodes the administration of justice and undermines the guarantee of the protection of human rights.5f4170d33758 In a 2021 UN General Assembly Resolution, Member States expressed concern about ‘the negative impact that all forms of corruption … can have on access to basic services and the enjoyment of all human rights’. They further recognised that corruption ‘can exacerbate poverty and inequality and may disproportionately affect the most disadvantaged individuals in society’.1ca289c4476f

In Honduras, the impact of corruption on human rights is pronounced. Corruption undermines access to education, health care, and basic services and exacerbates poverty.5476640ae54b With an estimated 10.6 million people, Honduras is ranked 157 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s CPI in 2022, making it among the countries with the highest perception of corruption risk.a8db8e1fd791 Since the 12-year rule of the National Party ended in 2022 with the election of President Xiomara Castro, Honduras is experiencing a democratic opening, which is presenting opportunities for civil society to promote anti-corruption efforts.12f2a73548a8

The GAC-supported project Justice, Governance, and Fight Against Impunity in Honduras (2018–2023), implemented by ASFC, is integrating human rights and anti-corruption into efforts to promote access to justice for vulnerable populations. The project has three strategic objectives: (a) establishing and supporting a cohort of human rights lawyers, (b) training lawyers in human rights best practices, and (c) supporting strategic litigation and promoting a discussion on human rights and corruption.

Corruption is not a victimless crime. However, individuals generally do not have legal standing to seek redress, because corruption offences are often defined as a crime against the state.bd1d232825a5 The GAC-ASFC project is attempting to show the human rights impacts of corruption and to define how individuals are victims of it. A ‘lack of victim’ effect in corruption cases is often cited as the reason for low prosecutions and has been identified by investigators and prosecutors as leading to a more relaxed attitude towards a case timeline.9ad0e76dfb9b To overcome this effect, the GAC-ASFC project strives to place individual victims at the centre of the corruption complaint so that they can be part of the criminal justice process in combatting corruption.

The project is receiving global attention and is helping to inform jurisprudence on how individuals can be affected by corruption. The OHCHR has selected a case supported by the GAC-ASFC project for a global study that will inform OHCHR strategy on addressing the nexus between corruption and human rights.01a4138ae578 The case is part of the investigations known as the Pandora Papers, which revealed one of the largest corruption scandals in Honduras. The Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras, backed by the Organization of American States, documented the illegal appropriation of public funds, leading to charges against 33 public officers and politicians. The stolen funds had been intended for social aid to benefit low-income populations in rural areas, and the cancellation of the aid programme due to corruption has had a direct impact on the human rights of the intended beneficiaries. The OHCHR selected the ASFC-supported case for their study for two purposes: (a) to demonstrate how corruption has an impact on human rights, and (b) to identify good practices on access to justice for victims of human rights violations due to corruption. ASFC is collaborating with the OHCHR in its research by providing information on the context, the legal file, and the national legal framework, and by supporting the OHCHR field research mission.b067adeb41de

With a new government in office in Honduras, the GAC-ASFC project is taking advantage of a window of opportunity to push for anti-corruption reforms. Accordingly, GAC and ASFC have designed a project extension with an increased anti-corruption focus. The project will work directly with the Anti-Corruption Commission, established by the Honduran Congress, to help develop the Commission’s agenda and to involve civil society in its work.7a7faa4a7209 The GAC-ASFC project demonstrates the benefits of multi-year, multi-phase programming, which enables learning and the adaptation of interventions in response to changing levels of political will to address corruption. With the opportunity to work directly with the state, the project may be able to shape anti-corruption reforms more directly in Honduras.

Connecting anti-corruption practitioners globally

Anti-corruption practitioners who are going up against powerful elites and seeking to disrupt power structures face significant challenges, including threats, intimidation, harassment, murder, and abusive lawsuits, among other tactics.8f52de5f42a0 Yet there are few protective mechanisms they can rely on. The long-running Corruption Hunter Network (CHN) is addressing this gap by supporting a small transnational network of investigators and prosecutors who meet in an informal setting to share their experiences, insights, challenges, and lessons learned, and to support each other.4fbd041ff43c The network has convened semi-annual meetings with 20–25 participants from around the world for the past 17 years.

French magistrate Eva Joly founded CHN in 2005 with the idea that investigators such as herself needed a transnational network to counter the networks used by corrupt officials and organised criminal groups.a9955422f093 In 1994, when Joly opened an investigation into the Paris-based oil company Elf Aquitaine, she discovered networks of hidden power and corruption woven through the circles of the French elite. As she investigated corruption among French politicians and other prominent individuals, she experienced personal threats. Joly was able to make breakthroughs in her investigation thanks to cross-border cooperation with magistrates and investigators in Switzerland.34243d1abbc5 Her experience led her to conceive of the idea of a network to provide investigators of grand corruption with cross-border support and cooperation. Criminals are not hindered by laws and regulations, and Joly saw the need for a means to ‘get around the formalistic nature of international cooperation’ among anti-corruption practitioners.4e46ce49c656

Participation in CHN is global, with individuals joining from Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, France, Germany, Malawi, Nigeria, Norway, São Tomé and Príncipe, Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Zambia.3bf90b676490 Participants provide each other with shared experience and insights, common purpose, moral support, contacts, and informal cross-border cooperation. The network has intentionally stayed small, resisting the temptation to expand, and implements a level of self-selection; individuals are invited to join the meetings based not on their position in an agency but on the merits of the work they have done. According to a representative of Norad who has coordinated the CHN since 2009, founder Joly wanted it to be a network of ‘practitioners’ and not ‘heads of agencies’.898824320d2c

According to a CHN participant, the meetings offer a rare opportunity for line prosecutors or operational prosecutors to interact with counterparts in other countries, to receive moral support from those who are experiencing similar challenges, and to speak with others who are also facing personal threats because of their work. The network helps anti-corruption actors overcome the bureaucracy of international mutual assistance by coordinating with each other in an informal setting.2b2bd060faa8

CHN participant Juan Argibay Molina has led a team of specialists on anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism for the Argentina Attorney General’s Office for the past ten years. For him, the CHN enables cross-border information-sharing that is practical and useful. Argibay states, ‘The network made me see you can have no boundary. Before, I thought my work was important for me and my country, but [I] realise the type of cases we deal with will have impact in other countries . . . which is difficult [to achieve] if we only have formal legal assistance.’76d443a95700

According to another participant, who wished to remain anonymous,

‘You tend to lose hope. It takes too long, and bosses don’t make decisions they should make. You go in [to the meetings], you share, [you find that] many of your colleagues are facing the same challenges. They are victimised, they don’t get funding, they face persecution and prosecution. It gives you great strength [to know that] we are all facing the same challenges, and out of the meeting come great ideas of what to do and how to face these challenges.’c0d8ad49d5fd

Critical to the endurance of the Corruption Hunter Network has been the long-term support and coordination provided by Norad.e67f34430b4a During the founding of the network, participants discussed the possibility that it might run itself. However, this was ruled out due to the impracticality of expecting a group of diverse and busy investigators and prosecutors, scattered around the world, to organise and fund themselves.abe5bcfd09d4 Norad’s sustained support to the CHN has been reported by U4 in past studies and in a recent Norad evaluation of anti-corruption components of Norad’s development cooperation.9e73f7ad3a0c

Anti-corruption theories of change in justice sector programmes

Since the 1990s, development practitioners have adopted the theory of change method to increase critical thinking about how project interventions lead to desired results and outcomes.5ee88f73a32e A theory of change is a process map that looks at the linkages between programme components and at the preconditions and assumptions that enable the interventions to work.f00bf31dc79d A U4 study found that there is ‘little solid research and evidence on how anti-corruption interventions create change’. The study also found that change pathways are often not made explicit and that ‘the preconditions for success often are not addressed’.7e100bafa1a2 A leader in anti-corruption development assistance, USAID recently acknowledged that corruption has often been treated as a contextual challenge but that sectoral programmes are not addressing corruption directly.455185956ba1

We spoke with U4 partners, project implementers, and project participants to understand current anti-corruption theories of change within justice sector assistance. We are not judging, evaluating, or validating the theories offered, but we provide them as examples of current assumptions that may be guiding some justice sector assistance.

A recurring assumption stated by project managers is that promoting transparency and accountability in justice service delivery will contribute to the prevention of corruption. This theory of change was often offered when discussing projects that address corruption indirectly rather than explicitly. For example, the Sida-UNDP project discussed earlier is digitalising police contravention case management systems to achieve increased transparency and accountability in police service delivery. According to the UNDP project manager, in Moldova both the police and the public function as drivers of corruption, since for citizens, paying a bribe to the police is an efficient way to secure policing services.085c3010025f Digitalising police case management of contravention matters, project managers assume, will ensure that case information becomes more transparent, and this in turn will reduce the opportunities for police and the public to manipulate the investigation process.

Another theory of change that we see across many projects in the mapping is that building the capacity of justice sector actors will enable more investigation and prosecution of corruption. For example, this assumption underlies the UK/FCDO-funded Serious Organised Crime and Anti-Corruption Programme (2020–2025). The project aims to build the investigative capacity of anti-corruption agencies, financial investigation entities, and the media, among others, to close loopholes in the justice system that hinder the prosecution of cases.fb9987d9edf5

The same assumption also drives the UK/FCDO-funded project Building Sustainable Anti-Corruption Action in Tanzania (2017–2025). This project aims to enhance deterrence by the criminal justice system to reduce elite incentives for grand corruption and serious and organised crime (SOC). The project seeks to achieve this through three strategic objectives: (a) the criminal justice system is more effective in identifying potential grand corruption/SOC activity; (b) the system is more efficient in handling grand corruption/SOC cases; and (c) the system is more effective in recovering proceeds of crime.a3cdd10ed958

Furthermore, the assumption that strengthening prosecution capacity will combat impunity is being applied in several mapped projects. As described above, Norad’s Corruption Hunter Network supports networking among prosecutors from around the world to informally strengthen international cooperation in the investigation and prosecution of corruption. A GIZ project, Promoting the Rule of Law in the Northern Triangle of Central America (2022–2025), and an SDC project, Strengthening Systems to Combat Corruption and Impunity in Central America (2020–2024), both aim to reduce corruption and impunity and strengthen the rule of law in the Northern Triangle of Central America by increasing the prosecution of corruption.

These are some of the theories of change that we were able to identify in the mapped interventions, but it is by no means an exhaustive list. Since most projects in our case studies do not have anti-corruption as their primary objective, we found that change pathways to addressing corruption are not fully developed. Most projects incorporate a political context analysis, as discussed below. But we found a lack of direct linkages between project efforts and drivers of corruption in the implementing context, on one hand, and measurement of how anti-corruption will be achieved, on the other.

Political context and programme design

Context analysis is a critical component of theory of change thinking, and among the six case studies we found frequent tailoring of interventions to fit the political context of the implementing environment. In settings where the political will to tackle corruption is moderate or high, as in Moldova and Honduras, we found that U4 partners are introducing or adapting interventions to address corruption explicitly. In contexts where the government does not support anti-corruption efforts or has politicised anti-corruption for a narrow purpose, as in Bangladesh, U4 partners are addressing corruption through indirect approaches and without stating this objective explicitly.

Moderate to high political momentum to address corruption

In Moldova, the government is pursuing high-level governance reforms as it seeks EU membership. This has enabled the Sida-UNDP intervention, as discussed earlier, to partner with the Ministry of Internal Affairs to ‘change the business model’ of policing through the digitalisation of police case management.c5033e5c8823 According to the UNDP project lead, the programme supports the government’s top-level anti-corruption agenda.e227fd72980f In Moldova, there is no tension between the project’s anti-corruption approach and the government’s political agenda.

In Honduras, a political transition has been underway since 2022, with a new government in office that is publicly stating a commitment to combatting corruption. In response, the GAC-ASFC project is adapting its approach to address corruption more directly in a new phase.248572630b14 The project will support the Anti-Corruption Commission established by the National Congress of Honduras. It will also combat the role of political influence in the judicial system and advocate for the repeal of laws, passed by the former government, that give impunity to corrupt public officials.94beeda55c2b Nonetheless, international partners to Honduras are proceeding with some caution with regard to the government’s anti-corruption agenda.f06e9288807a The new government of President Castro wants to be seen to be addressing corruption because of domestic and political pressure for democratic reform. However, there is some wariness among some political observers who question whether the government may also be utilising an anti-corruption agenda to target and sideline political opponents in order to consolidate greater control.e5e8ad3bd5e4 In this context, the anti-corruption goals of the government may be multifaceted and require close monitoring and analysis by partners responding with anti-corruption assistance.

Low political momentum to address corruption

In Bangladesh the government does not prioritise addressing corruption. Corruption is endemic, and there is politicisation of anti-corruption efforts. Moreover, the state is not upholding due process guarantees, and security forces violate human rights with impunity.1a9028b0fca4 The long-running joint GIZ and UK/FCDO project is working directly with the government; GIZ refers to it as Justice and Prison Reform for Promoting Human Rights and Preventing Corruption (2008–2023), while UK/FCDO uses the title Access to Justice through Paralegal and Restorative Justice Services in Bangladesh (2013–2023). The project is therefore limited in its ability to address corruption explicitly, given the sensitivity of tackling corruption in Bangladesh. Instead, it is supporting measures that can contribute to corruption prevention.

According to a UK/FCDO representative, the agency has changed the programme design over time to respond to changing levels of government engagement.8c0b219c786b GIZ representatives have described the project’s anti-corruption effort as indirect, saying that they are ‘not holding up a mirror’ to the government because implementation of the project depends on government agreement. For example, the project’s paralegal activities depend on the goodwill of government officials, who can authorise paralegals to enter prison facilities to provide legal aid services to detainees; calling out corruption and human rights abuses by prison officials could jeopardise this access. Rather, GIZ is working with the government to promote transparency and accountability. This includes encouraging partnerships between government and NGOs; providing paralegals to help citizens navigate the justice system with credible information to mitigate the risks of bribery; introducing tools to improve transparency and accountability in prisons, such as codes of conduct; and strengthening mechanisms to give citizens alternative pathways to dispute resolution outside the formal system in contexts where corruption is prevalent.8cce99ecccec These strategies are expected to have the cumulative effect of helping to prevent corruption in a context where it is difficult to combat it directly.

Gender integration in mapped interventions

We captured a rough snapshot of the level of gender integration in the mapped interventions by identifying those that explicitly reference ‘gender’, ‘women’, ‘girls’, or ‘lesbian, gay, bisexual, transexual, and intersex (LGBTI)’ – or some variation thereof – in the project description. We found that around 36% of the interventions (63 of 177) used one or more gender-related terms in the project title, project description, area of focus, or DAC CRS purpose code, or included a DAC gender policy objective marker.533377fb74e2 As a reflection of Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, GAC had the highest proportion of projects referencing gender or support to women and girls, at 77% of its interventions (34 of 44).

We then sought to identify, among the case studies, interventions that made explicit reference to both gender and anti-corruption. We found that the GIZ-UK/FCDO project in Bangladesh did this. According to a GIZ representative, women are disproportionately impacted by corruption when seeking justice in Bangladesh, and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms can reinforce gender-discriminatory norms. Accordingly, GIZ is implementing an initiative to provide alternative mediation processes that are fairer and more equitable. A GIZ representative stated that ‘for women to take on the role of a mediator is transformative’, as it represents a shift in power away from the dominance of men in community mediation.1ac06d5888f8 Empowering women’s leadership in the dispensation of justice can contribute to greater equality and transparency and help prevent corruption. The GIZ intervention is among the efforts by NGOs in Bangladesh to organise, modify, or monitor shalish, the local term for informal dispute resolution. In a 2014 U4 study, Stephen Golub found these NGO engagements help ‘prevent touts or corrupt local leaders from extracting payments, favours, or obligations from disputants in exchange for exercising their influence in a shalish’.0d5c83727da0

In the other five case studies, we did not find any examples of interventions simultaneously integrating gender equality and anti-corruption. In interviews, project implementers acknowledged that the link between promoting gender equality and doing anti-corruption remains unclear and requires further study.

Considerations and a way forward

With less than half of the mapped justice sector interventions applying an anti-corruption approach, and only 18% of them addressing corruption directly, more attention should be paid to anti-corruption integration in justice sector assistance.

In particular, we found few legal aid interventions directly addressing corruption, even though legal aid represents a high proportion of the interventions mapped. This includes the provision of free legal information, advice, accompaniment, and representation to marginalised populations. We heard from legal aid implementers about the challenges of working directly with governments while simultaneously calling attention to corruption in justice institutions. Legal aid providers depend on government goodwill to gain entry to justice institutions such as courthouses and prisons, and calling out corruption by public officials could jeopardise this access. Yet legal aid providers who assist marginalised populations are likely to encounter or become aware of corruption in the justice system in the course of their work. Marginalised populations, particularly women, are the most vulnerable to corruption.59f4c3b8d5ca The integration of anti-corruption perspectives into legal aid assistance is one way to support marginalised populations and mitigate their risk of exposure to corruption. However, any such integration should factor in the risk of a potential backlash from authorities that could jeopardise the ability of legal aid providers to continue assisting vulnerable citizens.

We heard anecdotally about the practice of ‘doing anti-corruption without naming it’, a phrase that describes indirect approaches to addressing corruption. These are useful in contexts where the government does not support anti-corruption efforts and where addressing corruption is a sensitive matter that could lead to a backlash. By not labelling an intervention as an anti-corruption measure, development practitioners may be able to address corruption while avoiding government scrutiny. There is also an emerging perspective that indirect approaches aimed at supporting deeper changes to governance or society may be more effective than policies and institutions that specifically target corruption.da860ab946d8 However, if anti-corruption is not named as a component of a project, even if only for the purpose of internal reporting, it is difficult to determine the extent of anti-corruption integration. It is also difficult to measure the anti-corruption effect if anti-corruption is not part of a project’s results framework.

Moreover, the mandate and focus of implementers can shape the scope of anti-corruption efforts. For example, UNDP implements more of the justice interventions funded by U4 partners than does UNODC. UNDP is more likely than UNODC to address corruption indirectly, which contributes to making indirect anti-corruption approaches more prevalent than direct approaches in U4 partners’ overall justice sector assistance. Understanding implementers’ mandates, priorities, and expertise is a first step to figuring out how to integrate anti-corruption into justice sector assistance. Certain partners may choose to address corruption directly and explicitly. Others may prefer indirect approaches that avoid labelling interventions as anti-corruption, in some cases because they don’t have the mandate or strategic priority to address corruption directly.

As a way forward, U4 partners’ reporting on support for the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16.5, to ‘substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms’, may offer data relevant to an assessment of anti-corruption mainstreaming. We learned after beginning the study that some U4 partners may be reporting on SDG 16.5. In future, we suggest an exercise to collate and compare U4 partners’ SDG 16.5 reporting in order to understand, among other things, the extent of anti-corruption mainstreaming in their projects. Alternatively, U4 partners could introduce internal reporting of anti-corruption mainstreaming or share periodic snapshots of anti-corruption integration in justice sector assistance.

Given the centrality of the justice system in the fight against corruption, the integration of anti-corruption approaches in justice sector assistance warrants further attention. Particular attention should be given to understanding the nature, scope, and effectiveness of indirect approaches, since they remain more common than direct approaches in the interventions covered by our study.

Annex

U4 partners’ anti-corruption approaches in justice sector assistance

- The CPI ranks 180 countries and territories around the world by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, scoring them on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). In 2022, Transparency International found that the global average score among the 180 countries assessed had remained at 43 out of 100 for over a decade.

- U4 is a permanent centre at the Chr. Michelsen Institute in Norway.

- According to Boehm (2014, p. 1), ‘mainstreaming anti-corruption means integrating an anti-corruption perspective into all activities and levels of an organization, a sector, or government policies’. See also United Nations Development Programme (2008).

- Boehm (2014, p. 3).

- Jennett, Schütte, and Jahn (2016).

- U4 (2023).

- European Commission (2022).

- European Commission (2022, p. 28).

- European Commission (2022, p. 12).

- United States Agency for International Development (2022, p. 7).

- The OECD DAC currently has 32 members, including the European Union.

- Denmark, Finland, Germany, and Sweden.

- The omitted partner was the Danish MoFA. As we received their input after finalising our project selection, we were unable to conduct key informant interviews needed to develop a case study.

- We received additional submissions from the Danish MoFA on 11 October 2023 after sharing a draft of this report.

- For example, the project titled Access to Justice through Paralegal and Restorative Justice Services in Bangladesh has run for ten years, with contributions from the UK of £35,823,840.

- As DAC members, U4 partners are required to report their ODA through the CRS system. The CRS lists codes, names, and descriptions used to identify the sector of destination of a contribution. See OECD, Purpose codes: Sector classification.

- 26 of 174 mapped interventions.

- 10 of 174 mapped interventions.

- 11 of 174 mapped interventions.

- 11 of 174 mapped interventions.

- 16 of 174 mapped interventions.

- 53 of 174 mapped interventions.

- OECD Development Co-operation Profiles for Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, and Sweden, 2023.

- 55 of 174 mapped interventions.

- 30 of 174 mapped interventions.

- UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (2023b).

- GIZ, 6 of 43; Sida, 2 of 19; Finland, 1 of 8; GAC, 1 of 44.

- See the Annex for a disaggregated list for each U4 partner.

- Finland MoFA, 4 of 8 interventions; UK/FCDO, 6 of 17 interventions; Sida, 5 of 19 interventions; Norad, 4 of 16 interventions; SDC, 4 of 20 interventions; GIZ, 9 of 43 interventions; GAC, 7 of 44 interventions.

- Jackson (2020, p. 8).

- Jennett, Schütte, and Jahn (2016).

- See the Annex for a disaggregated list for each U4 partner.

- United Nations Development Programme (2008, p. 9).

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- Santiso (2021).

- As stated in Article 10 of the Contravention Code of the Republic of Moldova, available in the International Labour Organization NATLEX database, ‘a contravention is an illicit action or inaction with a lower level of social danger than a crime that is committed with culpability, that encroaches upon the social values protected by law and . . . is liable to a sanction’.

- United Nations Development Programme (2022).

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- European Union and Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Moldova (2023).

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- GAN Integrity (2020).

- Transparency International (2022); United Nations Population Fund (2023b).

- EU4Digital (2023); Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (2022).

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- Santiso (2022).

- United Nations General Assembly (2021).

- García-Sayán (2018).

- International Council on Human Rights Policy and Transparency International (2010).

- Interview with ASFC Honduras representative, 17 May 2023.

- Transparency International (2022); United Nations Population Fund (2023a).

- Human Rights Watch (2023); ASJ (2020).

- U4 (2018).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2023).

- Interview with ASFC Honduras representative, 17 May 2023.

- Email from ASFC director, 11 September 2023.

- Interview with GAC Honduras representative, 5 May 2023.

- Interview with Norad representative, 23 March 2023; interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023; interview with Juan Argibay, 4 May 2023. See also U4 (2018).

- Lemaître (2022).

- Interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023.

- Ignatius (2002).

- Interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023.

- Interview with Norad representative, 23 March 2023.

- Interview with Norad representative, 23 March 2023.

- Interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023.

- Interview with Juan Argibay, 5 May 2023.

- Interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023.

- Schütte (2020, p. 8); Nordic Consulting Group (2020).

- Interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023.

- Interview with CHN Participant A, 4 April 2023; interview with Juan Argibay, 4 May 2023.

- United States Agency for International Development (2022, p. 7).

- Johnsøn (2012, pp. 3, 39).

- For a more detailed discussion of anti-corruption theories of change, see Johnsøn (2012).

- Vogel (2012, p. 10).

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (2023a).

- UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (2023b).

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023.

- Interview with UNDP Moldova representative, 10 April 2023; see also United Nations Development Programme (2022).

- Interview with GAC Honduras representative, 5 May 2023; interview with ASFC Honduras representative, 17 May 2023.

- Interview with ASFC Honduras representative, 17 May 2023.

- Interview with GAC Honduras representative, 5 May 2023.

- Interview with GAC Honduras representative, 5 May 2023.

- Freedom House (2023).

- Interview with UK/FCDO Bangladesh representative, 9 April 2023.

- Interview with GIZ Bangladesh representatives, 1 May 2023.

- A higher rate of gender mainstreaming might be found with further validation against partners’ DAC reporting, which is outside the scope of this study.

- Interview with GIZ Bangladesh representative, 1 May 2023.

- Golub (2014, p. 3).

- Camacho (2021).

- Jackson (2020, p. 8).