Query

Please provide an analysis of corruption risks in the secondary education system and secondary education school management in Ukraine, particularly from the perspective of academic integrity and resource management.

Caveat

This Helpdesk Answer focuses on the secondary education level, and not the primary or tertiary (or higher) levels. Nevertheless, it references concepts such as the “New Ukrainian School” and sources such as the 2022 risk assessment undertaken by the National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP), both of which cover primary and secondary education; furthermore, other terms such as “vocational education” cut across secondary and tertiary levels in the Ukrainian context (IAB-Forum 2022). For the purposes of this paper, these should be considered as referring to the secondary level.

Corruption can manifest in diverse ways and affect all levels of the education system (UNESCO-IIEP 2023). Accordingly, this Answer does not purport to equally address all corruption risks existing across Ukrainian secondary education as documented in the literature but instead highlights select areas, such as academic processes and resource management, including financial, material and personnel resources.

Introduction

Sector-specific research on corruption in the education sector has advanced in recent years (Poisson 2010: 1). The literature has succeeded in demonstrating that corruption can occur at virtually all stages of the education service delivery chain, from school planning and management processes to the administration of tests (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017:3), and that it can manifest both as grand, large-scale corruption as well as petty corruption (Poisson 2010: 1).

Hallak and Poisson (2002: 17) provide the following definition of corruption in the education sector: “the systematic use of public office for private benefit whose impact is significant on access, quality or equity in education” and outline some of the main practices which may fall under this definition (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary of some of the main practices of corruption observed within the education sector, and their possible impact on access, quality, equity and ethics

| Areas of planning / management involved | Corrupt practices | Elements of education systems most affected |

| Building of schools |

Public tendering Embezzlement School mapping |

Access Equity |

| Recruitment, promotion and appointment of teachers (including systems of incentives) |

Favouritism Nepotism Bribes and pay-offs |

Quality |

| Conduct of teachers |

'Ghost teachers' Bribes and pay-offs (for school entrance, for the assessment of children, etc.) |

Access Quality Equity Ethics |

| Supply and distribution of equipment, food and textbooks |

Public tendering Embezzlement Bypassing of criteria |

Equity |

| Allocation of specific allowances (compensatory measures, fellowships, subsidies to the private sector, etc.) |

Favouritism Nepotism Bribes and pay-offs Bypassing of criteria |

Access Equity |

| Examinations and diplomas |

Selling of information Favouritism Nepotism Bribes and pay-offs Academic fraud |

Equity Ethics |

Sourced from Hallak and Poisson 2002: 20. Ethics and corruption in education: results from the experts workshop held at the IIEP - Paris, 28-29 November 2001.

The focus on impact speaks to the severity of corruption’s effects on educational outcomes. For example, by placing a strain on available resources, corruption increases the workload of teachers which can have a trickle-down effect on access to and quality of education services (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne, 2017:2). It can have further wide-ranging impacts by leading unqualified persons to take up professions where they have a duty of care (Kolomoyets et al. 2021) or causing students to become so normalised to corruption at school that they tolerate it or even engage in corrupt practices in their adult lives (Sologoub 2023). For example, analysis of a 2002 survey in Ukraine found that students who gave bribes during secondary school were 20% more likely to have attempted to bribe to be admitted to a higher educational institution, suggesting that corrupt practices adopted in the secondary sector may carry on to the tertiary (Shaw et al. 2015).

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:3) identify two main drivers for corruption in the education sector: the high stakes involved in educational achievement, motivating students and their families to compromise on integrity; and the typically large volume of funds allocated to the sector, which is often accompanied by a lack of effective oversight mechanisms. Indeed, the OECD (2017: 17) explains that everyday people may engage in corruption with the aim of solving problems in the education sector, such as perceived poor quality of teaching and the low provision of resources.

The dynamics of corruption in the education sector are at play in both developing and developed countries (Pyman and Kaplan n.d.). That being said, the manifestations of corruption in the sector and the necessary interventions designed to address it may depend on local contexts (Kirya 2019: 29). Indeed, features of an individual country’s education system and its wider political economy can contribute to an increased risk of corruption (Kirya 2019: 4-5).

In this vein, this Helpdesk Answer analyses corruption in the secondary education system in Ukraine. Corruption has repeatedly been recognised as a policy problem affecting Ukraine’s tertiary level education,5da38c59d7df but also the lower levels, as attested to by the recent commissioning of two comprehensive studies: the 2017 OECD Review of Integrity in Education; and the 2022 risk assessment undertaken by National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP). Efforts to curb corruption in the sector have been affected by the ongoing Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine launched in February 2022 (hereafter referred to as the Russian full-scale invasion) which has created new challenges outlined in further detail below.

This Helpdesk Answer first describes the structure of the secondary education system in Ukraine, including the policies and legislation shaping it. It then outlines the forms of corruption prevalent in the sector as documented in the literature, focusing on those pertaining to academic and finance related processes. Finally, it surveys measures that have been undertaken to address corruption in Ukraine’s secondary education sector, as well as drawing on other best practices.

Secondary education sector in Ukraine

Structure

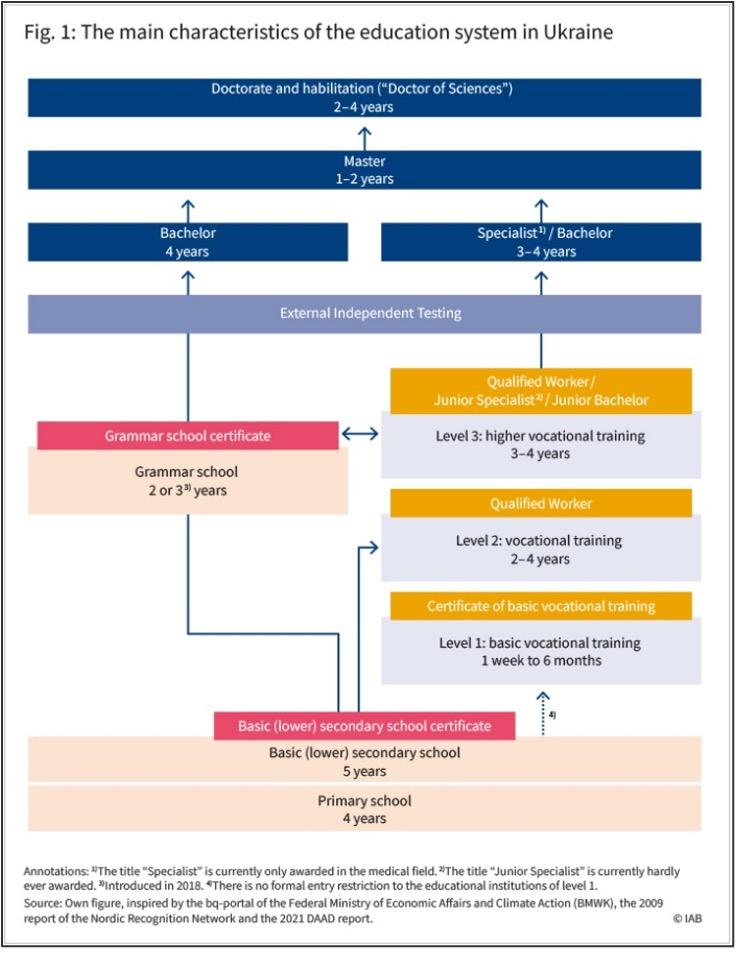

Article 53 of the 1996 Constitution of Ukraine grants the right to education, stipulating that “[t]he state ensures accessible and free pre-school, complete general secondary, vocational and higher education in state and communal educational establishments”. A visual overview of the current educational system in Ukraine is provided in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. An overview of the education system in Ukraine

Source: IAB-Forum. 2022. Vocational training in Ukraine – an overview.

Upon finishing pre-school education, all children attend a common basic secondary school for a period of five years. At this point, they take final examinations and either enter an academic-orientated secondary school (also known as grammar schools) or vocational education. The former track enables bachelor studies in academic higher education institutions. There are a diverse range of such grammar schools, most of which are general (also known as neighbourhood schools), but also gymnasiums, collegiums and lyceum which offer different kinds of academic specialisation (OECD 2017: 54).

The latter encompasses both schooling and practical placements and is divided into three further levels which have varying durations and cater to different vocations. For example, the basic vocational training provided under Level 1 is geared towards positions in industry and service sectors, while the Level 2 vocational training pertains to roles such as office clerks performing accounting tasks. Level 3 higher vocational training concerns professions that require further education at a tertiary level vocational institution (IAB-Forum 2022).

Admission into third-level institutions is determined by a mixture of factors, including the school leaving certificate (SLC) grade point average and marks attained in the External independent testing (EIT). The former is a result of continual testing in secondary school while the latter is a one-off externally administered set of examinations (OECD 2017: 70). However, other criteria such as performance in national knowledge competitions (olympiads) or affirmative action policies can also influence admission.

In 2020, it was estimated that 44% of the Ukrainian population had completed secondary education and that approximately two-thirds of active secondary level students were on the academic track and one-third on the vocational track (OECD 2022).

Actors, legislation and policies

The main institutional actors involved in the secondary education system are as follows:

- Ministry of Education and Science (MES): leads the formation of national policy, such as the approval of teaching programmes and materials, and oversees education subventions to local government units for such purposes as teaching staff salaries, refurbishing of hub schools or improvement of sanitary facilities (NACP 2022: 9; Huss and Keudel 2021: 14).

- Local government units (LGUs):d89cc195257b are responsible for ensuring access to education. This entails overseeing funding from the local budgets and managing the network of educational institutions (such as schools or vocational institutions) in a respective territory, organising inclusive learning spaces and facilitating transportation. LGUs may establish education departments at region (oblast), district (rayon) and community (hromada) levels tasked with coordinating information flows to education institutions, managing education subventions, accounting and procurement. LGUs appoint education institution principals and have partial responsibility for ensuring the use of funds is reported to the wider public (NACP 2022: 9).

- Educational institution management:refers to the managers of secondary schools or vocational institutions; for example, school principals. They are generally endowed with a broad degree of autonomy in, for example, the management of material and human resources of the educational institution.

Other actors include pedagogical councils (comprised of teachers) and parents’ committees (NACP 2022: 9).

This decentralised model of actors and their responsibilities developed through a series of legislative acts adopted in recent years, including:

- Law of Ukraine on Professional (Vocational And Technical) Education (1998) (revised as of 2023)

- Law of Ukraine on Education (2017)(revised as of 2024)

- Law of Ukraine on the Professional Pre-higher Education (2019) (revised as of 2023)

- Law on Secondary Education (2020)(revised as of 2024)

Corruption within the sector is generally addressed separately through anti-corruption legislation, including:

- Law of Ukraine on Prevention of Corruption (2014) (revised as of 2023)

- Criminal Code of Ukraine (2001)(revised as of 2024)

Responsibility for addressing domestic corruption in Ukraine is divided between several entities:14f16f961db7

- National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP): designs and implements policy to prevent corruption

- National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU): investigates suspected cases of corruption

- Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office (SAPO): prosecutes cases of corruption referred by NABU

- High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC): administers justice in cases referred by NABU

- Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA): responsible for tracing, confiscating and managing assets derived from corruption

Funding and expenditure

Levels of government expenditure on education in Ukraine are similar to the regional average and higher than the global average (see Table 2).

Table 2. Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP) based on comparable estimates from 2021.

|

Data point |

% of GDP |

|

Ukraine |

5.1% |

|

Europe & Central Asia |

5.0% |

|

World |

4.2% |

Source: World Bank, 2023.

The Ukrainian school system relies on a mixture of funding sources (NACP 2022: 12-13; разом проти корупції 2020: 8):

- national budget: this often takes the form of education subventions to local government units allocated for specific purposes, such as the payment of teachers’ salaries. The use of these significantly decreased between 2017 and 2020, but emerged again due to ad-hoc costs incurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. While generally considered to be key to improving the quality of education, there have seen some reported cases of misuse of education subventions (Бондаренко 2020; NACP 2022: 18)

- regional/local budgets

- educational institutions’ own revenues

- charitable donations from parents and the wider community (NACP 2022: 12-13)

The 2014 decentralisation reforms and the educational reforms under the appellation “New Ukrainian School” constituted a general shift in terms of management of funding and expenditure from the national government to LGUs and educational institutions (Huss and Keudel 2021: 14). Educational institutions are required to report their sources of funding online, although the form such reporting should take is not precisely regulated (NACP 2022: 12).

Russian full-scale invasion

The Russian full-scale invasion has disrupted all areas of life in Ukraine, including education in the forms of the destruction of many school buildings and the displacement of thousands of teachers and school-age children. The former has triggered new costs in the form of school repairs and the construction of school bomb shelters, while the latter has led to significant challenges in verifying the number of children in each locality who should be in school (Zhurzhenko 2022; NACP 2022: 17). On top of this, the reallocation of resources necessitated by the invasion led to a 10% reduction of the education subvention over 2022/23 (NACP 2022: 10). In 2023, the national government allocated UAH87.5 billion (approximately €2 million) for teachers’ salaries in 2023, an almost 20% decrease compared to 2022 (Farbar 2023).

Respondents to a 2023 survey of persons working in the wider education sector overwhelmingly agreed with the sentiment that corruption needed to be addressed in the sector, but that this would be difficult in light of the Russian full-scale invasion and socio-economic conditions (Hasiuk et al. 2023).

Corruption within secondary education in Ukraine

Levels of corruption

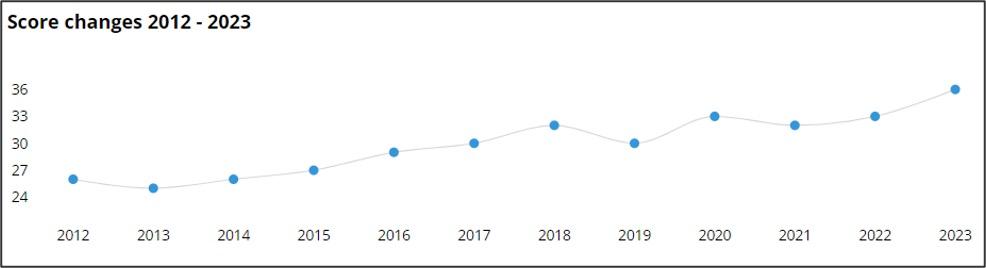

Corruption is generally perceived by the public to be a serious issue in Ukraine. In a 2023 survey, respondents ranked it the third most important challenge facing the country after Russian armed aggression and increase in the cost-of-living (NACP 2023). Ukraine received a score of 36/100 in the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index, thus placing it 104 out of 180 countries (Transparency International 2024); however, this score has been gradually improving since 2012 (see Figure 2). Several international actors, for example, the International Anti-Corruption Advisory Board (IACAB) associated with the European Union Anti-Corruption Initiative (EUACI), have recognised that Ukraine has made significant progress to counter corruption (EUACI 2023).

Figure 2: Evolution of Ukraine’s Corruption Perception Index Score

Source: Transparency International 2024. Corruption perceptions index.

Available statistics specific to the education sector also indicate the existence of corruption within the sector. The 2016 Global Barometer survey found 4% of respondents had paid a bribe in the previous 12 months when using public schools (Transparency International 2016).

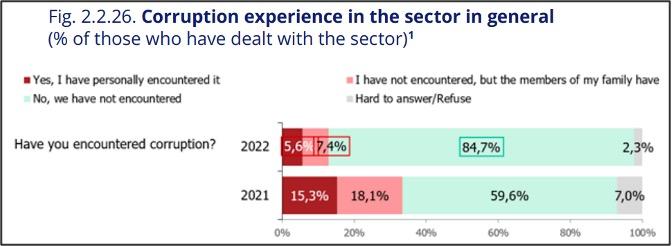

The NACP (2023) carried out a survey asking respondents if they had encountered corruption in primary and secondary educational institutions over the last 12 months. In 2022, 5.6% of respondents said they had encountered corruption, while 7.4% said they had not personally but members of their families had; however, these represented significant decreases compared to 2021 where the same response levels were 15.1% and 18.1% respectively (see Figure 3).

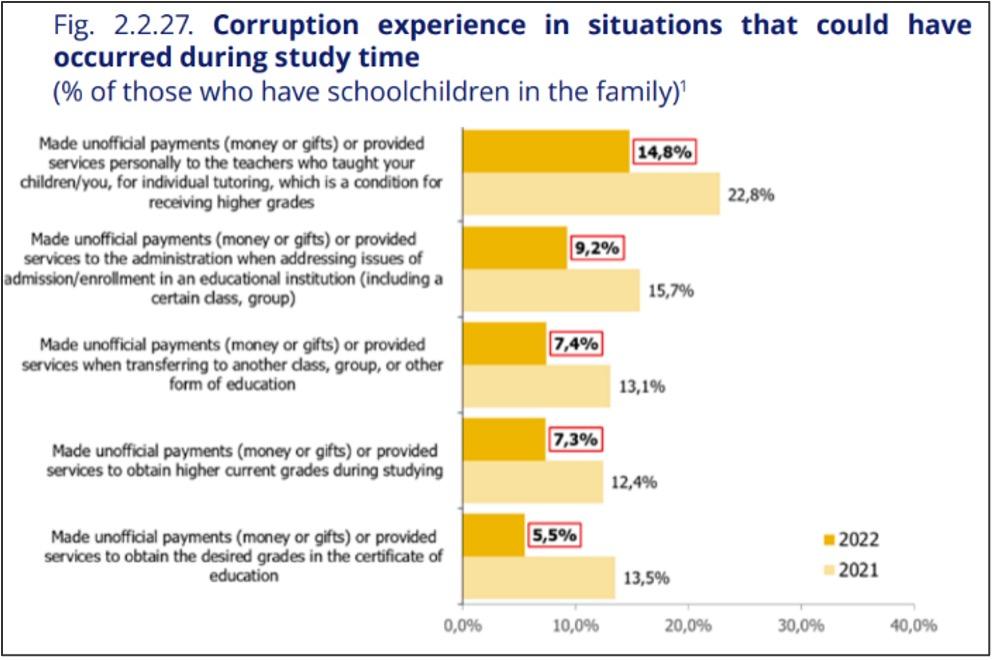

In terms of the forms of corruption respondents, encountered, this primarily constituted unofficial payments (money or gifts) exchanged for private supplementary tutoring, admission or enrolment into educational institutions, transfers to other classes and higher grades for in-school tests (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Results from NACP survey on experiences of corruption in the primary and secondary education sectors

Source: NACP, 2023: 95 (translated from Ukrainian). Corruption in Ukraine 2022: Understanding, perception, prevalence.

Figure 4: Results from NACP survey on forms of corruption encountered in the primary and secondary education sectors

Source: NACP 2023: 96 (translated from Ukrainian). Corruption in Ukraine 2022: Understanding, perception, prevalence.

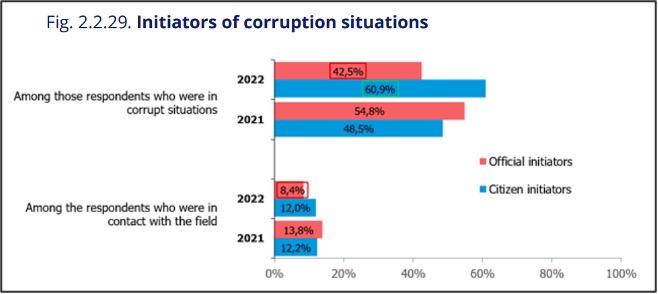

The results across 2021 and 2022 indicate overall balanced levels of school officials and citizens being responsible for initiating such incidents of corruption (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Results from a 2022 survey on initiators corruption in the primary and secondary education sectors

Source: NACP, 2023: 97 (translated from Ukrainian). Corruption in Ukraine 2022: Understanding, perception, prevalence.

Risk areas

These statistics give a degree of insight into the forms of corruption affecting secondary education in Ukraine, although further evidence points to an even wider range of risk areas.

In 2022, the NACP carried out a risk assessment of primary and secondary education which identified 35 corruption risks across four main processes: funding; the appointment of heads of educational institutions; the administration of educational institutions (for example, food supply schemes, property and land management, personnel management); and the academic process (for example, admissions and grading). It also identified three overlapping drivers behind these risks: education officials’ misuse of discretionary powers; legal uncertainty; and the existence of an organisational culture that promotes dishonesty (NACP 2022: 6).

A selection of these risks are described in the following sections, along with insights from other studies and sources.7a4cdef773e3

Academic processes

The NACP highlighted the “sale” of higher grades or making the awarding of higher grades conditional on private tutoring as risks facing Ukrainian primary and secondary schools (NACP 2022: 80, 92). Indeed, Kahkonen (2018) reports cases of parents paying bribes for their children to be admitted into a particular school, to obtain better grades or for private tutoring.

This often takes the form of irregular payments or gifts. Kolomoyets et al. (2021: 702) describe how the originally well intentioned culture of gift-giving to teachers in Ukraine has deteriorated, with many students or their families giving expensive gifts with a view to obtaining something in return.

Admissions

As explained above, there is a diverse range of schools in Ukraine catering to different specialisms. Furthermore, many are associated with different perceived levels of quality, but there can also be a mismatch between demand for admission and the number of available spaces, both of which can lead to competition for spots (OECD 2017:56).

In Ukraine, “neighbourhood secondary schools” are required by law to enrol all children living in their surrounding area that apply to the school (OECD 2017: 55-57); conversely, specialised schools can implement competitive admission procedures in line with certain guidelines. However, the OECD integrity review team heard cases of both neighbourhood and specialised schools using unauthorised forms of testing to unfairly influence admission processes, which led many parents to feel their children were unfairly rejected from schools. Since then, the introduction of digital enrolment systems for many secondary schools has in part reduced this risk (ACC 2022).

However, the Russian full-scale invasion has also triggered new corruption risks, namely the falsification of enrolment in educational institutions with the aim of avoiding military conscription into the armed forces of Ukraine. In 2023, the general prosecutor’s office reported it had uncovered a suspected scheme in which the head of a technical and vocational education and training (TVET) institution in Cherkasy received approximately UAH (Ukrainian hryvnias) 2,000 per month (approximately €49) from young men to enrol them in studies; the men reportedly did not intend to participate in studies but enrolled with the intention of avoiding conscription (Донцова 2023).

Learning

The MES informs the design of secondary level examinations based on national curricula (OECD 2017: 70). However, with the notable exception of the EIT, most tests in secondary schools in Ukraine are administered in-house and assessed by the institution’s teachers as per their respective subjects. This includes, for example, the state final exam (SLC), which has high stakes because SLC results form one of the criteria for admission to tertiary level educational institutions.

While the MES has promulgated national level evaluation standards, grading relies to a large extent on the teacher’s subjective assessment of the student’s performance in a test. In its risk assessment, the NACP found this gives teachers the opportunity to obtain an illegal benefit through manipulation (NACP 2022: 80). Likewise, the OECD (2017: 69) found that the culture of accepting gifts can motivate parents to influence teachers to alter their children’s grades.

Corruption may also arise before the actual marking takes place. For example, there was a case in 2016 where a group of students bribed a TVET official to gain illicit access to examination materials (Стопкоп 2016).

Teachers’ grading is, in principle, subject to the review of the heads of the educational institution (OECD 2017: 78). However, evidence suggests that school principals often ignore suspected mismarking (разом проти корупції 2020: 9). Furthermore, the OECD review team (2017: 78) found that visits made by school principals and local education inspectors were not focused on grading practices and thus constituted a weak check.

Additionally, unfair practices can be difficult to detect as schools must keep individual student’s grades confidential (разом проти корупції 2020: 9). Nevertheless, an analysis by the Ukrainian Centre for Education Quality Assessment (CEQA) determined there was an overall higher degree of overmarking in the SLC tests administered in-house compared to the EIT tests which is administered externally, leading the average scores in the former to become highly inflated over time (OECD 2017: 73). However, it is not clear how much of this inflation was attributable to corruption as opposed to other factors behind overmarking, such as teachers trying to give the benefit of the doubt to generally high-performing students.

A 2023 survey of 1,563 students from Ukrainian secondary schools (academic and vocational) found that 26% of respondents agreed with the statement that cheating in their schools was “very common”, while 58% said rather common (Sologoub,2023).94ee81ae3a18

Private tutoring

In 2017, the OECD review team heard testimonies that private supplementary tutoring was being provided to students on a widespread basis by their school teachers (OECD 2017:92). This took both the forms of the teacher giving the favoured student extra support during school hours or alternatively in separate tutoring sessions outside school hours (OECD 2017:93). Іщенко (2019) concludes that many parents often do not trust the quality of regular teaching in Ukrainian schools and pay for private tutoring to ensure their children perform well on testing. A 2016 survey of 584 upper secondary school graduates from Ukraine found that 69% of them took private lessons, primarily to achieve higher grades and thus increase their chances of entering prestigious universities (Długosz 2016).

While the practice of teachers providing private tutoring to their own students is not prohibited under Ukrainian law, the OECD (2017:95) argued it creates undesirable incentives by resulting in preferential treatment given to some students to the detriment of others whose families are unable to pay. In other cases, it amounts to clearer cases of corruption. Іщенко (2019) reports incidents of teachers deliberately manipulating grades with the aim of making it necessary for students to undertake private tutoring to obtain a higher grade. Respondents to the OECD’s integrity review (2017: 95) also alluded to cases of teachers giving students unduly low marks so that parents will offer informal payments or gifts in exchange for private tutoring.

Resource management

In its corruption risk assessment, the NACP (2022: 17-31) identified a number of resource management-related risks in Ukrainian schools that can lead to losses in terms of financial and material resources:

- artificial increase in the number of students

- biased allocation of budget funds between educational institutions

- abuse in the allocation of funds for repair work

- embezzlement of residual educational subvention

- corruption risks in the process of managing extrabudgetary funds

- charitable contributions in exchange for school enrolment

- regular voluntary and forced collection of charitable funds

- double financing of the same needs

- waste or misappropriation of charitable contributions

Parents’ donations

Kolomoyets et al. (2021) argue that by making secondary education free of charge, Article 53 of the Ukrainian constitution should entail that the state is fully responsible for financing it.

However, government funding in Ukraine is insufficient to meet all education needs (Huss and Keudel 2021: 21), with schools often relying on donations from parents and the wider community. These are often collected with the aim of funding everyday resources, such as textbooks, chalk and soap, but also more substantial technological upgrades such as interactive whiteboards (Sologoub 2023). The MES has clarified that the collection of donations is illegal when initiated by school officials; however, when it occurs from the parents’ initiative (especially through parents’ committees) it is more difficult to legally address (Transparency International 2021b).

Indeed, Sologoub (2023) highlights that parental donations may be collected by schools with the aim of bypassing lengthier, but also more robust, public procurement procedures required for budget funds.

Although the proportion of parents making donations has been decreasing, it is still substantial. The OECD (2017: 21) found that up to 90% of parents with school children reported they had made such donations, and based on statistics from 2014/15, estimated that such donations accounted for up to 5.4% of total secondary school expenditure (see Table 2).

Table 2: Private expenditure on pre-school, primary and secondary education (2014/2015)

| Private expenditure | |||

| Permissible sources | UAH million | Percentage of total expenditure | |

| Public pre-schools | Parental and other charitable contributions | 547 | 3.5 |

| Public schools |

Parental and other charitable contributions Fee-based services Lease of equipment and premises |

2 419 | 5.4 |

Source: OECD 2017: 39. OECD reviews of integrity in education: Ukraine 2017.

The number of parents making such donations has been decreasing in recent years, falling from an estimated 70% in 2017 to 55% in 2020 (TI Ukraine 2020).

Several corruption risks have been identified with the reliance on parental donations. Huss and Keudel (2021: 15) find that most donations are made by parents in cash and are typically kept as such by school administrators, despite a legal obligation to deposit such donations in a separate treasury account and maintain a list of income and expenditures and receipts. This, in combination with a lack of budgetary reporting by school authorities, can create a risk of “double funding”, namely that school officials request parents’ donations for needs that have already been financed. For example, they may have already received funds from a purpose-driven educational subvention but failed to have declared this (NACP 2022: 18).

The OECD review team found that donations can also provide a cover for parents making illicit payments in exchange for services such as higher grades, but it can also create an unhealthy dependence of the school on parents who may wish to influence teachers to favour their children (2017: 84).

Furthermore, the OECD (2017: 43) flag a high risk that officials gain kickbacks through fraudulent invoicing for the goods or services purchased through the donations. The team describes testimony from a vendor of foreign-language textbooks that awarded discounts to schools for purchasing in bulk, but claimed most parents still end up paying the full retail price for individual books, meaning the school staff retain the difference.

Procurement

The OECD integrity review team (OECD 2017:42) reported that procurement fraud schemes are common forms of misappropriation affecting the education sector. Several recent cases indicate the continuance of this trend.

In 2023, police initiated criminal proceedings into officials from the education department of Poltava city council suspected of conspiring with several heads of educational institutions on the bulk purchase of laptops (Полтавщина 2023). Through the scheme, the suspects did not create an open tender but rather inflated the retail price of the laptops of one bidder by up to 80% and tried to retain the markup value; police noted the scheme was facilitated by imprecise guidelines on the purchase of such equipment.

In a separate 2023 case, the NABU was investigating a scheme involving an official from the Capital Construction Department of the Ivano-Frankivsk Regional State (Military) Administration suspected of conspiring with a private company in the construction of a school for UAH45.6 million (approx. €1.1 million). However, only UAH33.6 million was transferred to the company. The remainder was embezzled by the participants in the scheme who proceeded to launder it through shell companies; meanwhile, the construction of the school was only partially completed (Сила віри 2023).

In another recent case, the Dnipro City Council reported suspicions that school officials were signing off on and paying for substandard furniture, causing estimated losses of UAH3 million (more than €70,000) that were retained by a private company (Dnipropetrovsk Region Press 2023).

There are also reported cases of conflict of interest in procurement processes, affecting a range of material resources used in schools. For example, the OECD (2017: 23) pointed to gaps in Ukraine’s textbook acquisition process that create conflict of interest risks such as the fact that the names of textbook evaluators are made public. The NACP (2022: 54) also recognises conflict of interest risks in the procurement of school food supplies where officials may collude with local suppliers who provide overpriced or low quality food.

In a recent case, the director of a vocational school in Volyn region repeatedly entered into contracts for the provision of services with the private company co-founded by his father and failed to inform the Department of Education and Science of the Volyn Regional State Administration or the NACP of the conflict of interest (Район.Бізнес 2021).

Human resource management

Human resource management (HRM) in secondary educational institutions in Ukraine is also vulnerable to forms of conflict of interest and favourtism such as nepotism. For example, in 2023, the director of a vocational school in Lviv was fined for awarding salary bonuses to her son and daughter, who worked at the same school as a social teacher and a librarian respectively (Zaxid.Net 2023). In a similar case, the acting director of a school in Zabolottiv was found guilty of corruption related offences for employing close relatives and paying them bonuses (VSN 2023).

Another HRM related process that faces corruption risks is the appointment of heads of educational institutions (for example, secondary school principals). As noted by the NACP (2022:9), heads of educational institutions have broad powers in terms of organising academic processes and managing resources, making it important to safeguard the appointment process. However, there have been some reported cases of corruption. For example, in 2016 an inspection led by a regional body found evidence of corruption in the appointment of an interim school director in a school in Chortkiv; it was found that the candidate, a teacher in historical sciences, did not have the necessary social pedagogy qualifications to justify obtaining the more senior level role with a higher salary (Провсе 2016).The Law on Secondary Education (2020) contains several safeguards to mitigate these risks. It precludes anyone being found guilty of a corruption offence from being appointed as head of an educational institution. Furthermore, it outlines that appointments should be made under a competitive process. The founder of the educational institution has the authority to initiate and oversee this process, but decisions are made by a competition commission composed of members of the educational institution, the LGU administration as well as civil society. Furthermore, the competitive selection must be video-recorded and published online, and candidates must undergo competitive testing, for example, on legislation pertaining to secondary education. The selected candidate can only serve as the head of the particular educational institution for a maximum of two terms, lasting six years each (Oсвіта 2020; NACP 2022: 33-34).

The NACP report (2022: 35-42) identified that some systematic vulnerabilities in the process can expose it to favouritism; for the example, the discretionary powers accorded to the founder of the educational institution. This can lead to distorted outcomes such as the competition not Taking place, the biased composition of the commission or biased evaluation of its testing.

The report also highlighted that martial law implemented in response to the Russian full-scale invasion created a temporary exception to forgo the competitive process under certain circumstances (NACP 2022). Some concerns about abuse of this exception were raised not only in the NACP but also by the ombudsman for education Serhii Gorbachev. In October 2023, he called for the resumption of mandatory competitions for the appointment process in regions where the security situation allows it (Oсвіта 2023).

Anti-corruption measures

This section outlines a selection of existing anti-corruption measures that have been implemented in Ukraine to address the forms of corruption outlined in the previous section, as well as opportunities for scaling up measures.

Indeed, there is arguably significant potential in this regard, in the wake of the Russian full-scale invasion, as the national Ukrainian government and wider international community consider how best to integrate anti-corruption into reconstruction planning, including in sectors such as education (Jenkins 2023).

Risk management

The U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre defines corruption risk management as a specific set of procedures and requirements to detect, assess and mitigate corruption risks within an organisation (U4 n.d.). Focusing on addressing risks rather than actual manifestations of corruption can enable proactive preventive approaches (McDevitt 2011: 2), including in sectors where evidence can be difficult to gather. There are several signs that Ukraine has mainstreamed risk management approaches into the education sector. For example, it has commissioned domestic assessments in the form of the NACP’s 2022 corruption risk assessment, as well as allowed external assessments in the form of the OECD’s 2017 integrity review of Ukraine. The OECD’s review applied the integrity of education systems (INTES) methodology, developed specifically for the education sector, which inter alia, focuses on identifying and addressing the root causes leading to corruption in the sector (Kirya 2019: 5).

Ukrainian national institutions have also applied risk management approaches to secondary education, most notably the NACP’s 2022 corruption risk assessment which, in addition to identifying risks, contains many recommendations tailored to mitigate each risk. For example, the assessment recommends measures to proactively mitigate against possible corruption risks emerging as a result of the Russian full-scale invasion. It notes that there is currently no system in place for allocating funds for the repair of damaged educational institutions, which could result in fraudulent claims being made; the NACP therefore recommends the creation of an online system for recording and verifying the repair needs of educational institutions (NACP 2022: 21). The NACP also reviews legislation through a risk lens to ensure there is no lack of clarity that could enable corruption. For example, it carried out an examination of a draft resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine on the implementation of a project titled Vocational Technical Education Support Program in Ukraine, and determined that the procedure stipulated under the resolution for the use of budget funds towards the creation of “centers of professional excellence” was opaque and open to abuse (NACP n.d.).

Similarly, when the MES needed to procure over 100,000 laptops for teachers to facilitate distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, it set out clear guidelines on the tender processes, including the expected cost per laptop, in order to prevent the risks of misappropriation or conflict of interest (Transparency International Ukraine 2021a).

Other positive examples of a systematic risk management approach include the competitive selection process for the heads of educational institutions. The NACP report (2022) makes several recommendation on how to further enhance this process, such as standardising evaluation guidelines as well as built-in checks against the discretionary powers of the founders (NACP 2022: 35-42).

Kirya (2019: 26-27) argues that assessing corruption risks in education should be a country-led process, focus on solving local problems that are defined in a participatory manner so there is sufficient buy-in from powerful education stakeholders and grassroots groups. The NACP risk assessment lists different education stakeholders responsible for implementing recommendations, including the MES and parents, and therefore provides a strong basis for a participatory risk management approach.

Transparency

Albisu Ardigó and Chêne (2017:8) recommend the adoption and use of transparent and participatory budget processes “to monitor how resources are being allocated and allow public scrutiny and control over the use of education resources”.

Transparency-promoting tools in the education sector include the use of digital tools, forms of participatory budgeting, as well as public expenditure tracking surveys (Kirya 2019: 3). Reviewing the discourse on reconstruction in Ukraine, Jenkins (2023) found there is “broad consensus on the importance of open data initiatives and procurement safeguards”.

Transparency measures may be of particular relevance in addressing the corruption risks associated with parental donations and procurement.

In its risk assessment, the NACP (2022: 31) recommends the creation of instructions for the public on how to officially make donations, but which also demand accountability from education authorities and schools on how these are spent. Furthermore, it (2022: 55) recommends fostering greater cooperation between LGUs and educational institutions on ensuring market prices for school resources are known and adhered to, as well as facilitating public monitoring in this respect.

Ukraine has a strong legal basis for ensuring transparency in the education sector (see Box 1). For example, the NACP (2022:14) pointed out that there are robust reporting obligations for the spending of parental donations, although these are not always upheld by school authorities (NACP 2022: 4).

Box 1: Legislation on transparency in education and open data

Art. 30 §3 of the Law on Education (Parliament of Ukraine, 2017).

Educational institutions that receive public funds and their founders are obliged to publish on their websites estimates and financial statements on the receipt and use of all funds received, information on the goods, works and services received as charitable donations, indicating their value, as well as funds received from other sources not prohibited by law.

Art. 101 §1 of the Law on Access to Public Information (Parliament of Ukraine, 2011, amended 2015).

1. Public information in the form of open data* is public information in a format that allows its automated processing by electronic means, with free access at no cost, as well as facilitating further use.

Information providers are obliged to make public information available in the form of open data on request, publish and regularly update it on the unified State web portal of open data (https://data.gov.ua) and on their websites.

* The list of data sets to be published in the form of open data, requirements for the format and the structure of such data sets, and the frequency of their updating are determined by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine in Decree No. 855 from 21 October 2015. On Approval of the Regulations on data sets to be published in the form of open data (Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, 2015).

(Sourced from Huss and Keudel 2021: 17)

Several initiatives have been launched to support the operationalisation of such transparency provisions. Huss and Keudel (2021) published an analysis of the Open School online platform, which was developed by the Kherson based civil society organisation Union Fund with support from international partners. The platform provides a one-stop shop for educational institutions to report on the receipt and use of both budgetary and extrabudgetary funds and to share financing needs; such reports are made accessible to the public in a clear and standardised form (Huss and Keudel 2021: 19). As of 2021, an estimated 5% of Ukrainian educational institutions were using the Open School Platform.

Huss and Keudel’s research uncovered many anti-corruption benefits of the platform. For example, they cite a case where Open School was used by the Department of Education of the Kramatorsk LGU to prove they had already funded costs for which a school was seeking parental donations (Huss and Keudel 2021: 60).

Nevertheless, they heard evidence that many school principals are reluctant to upload the required information to the platform, viewing it as extra work (Huss and Keudel 2021: 42). Furthermore, while interviewed parents broadly viewed Open School as effective in reducing corruption, school personnel were much less positive (Huss and Keudel 2021: 46).ea447e097fba

Transparency International Ukraine (2023) also outlines how parents can use the Prozorro public electronic procurement system (developed by TI Ukraine but administered by the Ukrainian government) to make and specify the use of donations to schools (Transparency International Ukraine 2023).

In 2023, the NACP piloted a similar project,Educational Navigator, in five educational institutions with the aim of eventually mainstreaming it in all Ukrainian schools (Ukrinform 2023). The ongoing project aims to increase integrity, transparency and openness in Ukrainian schools through five key areas:

- educational leadership

- capable pedagogical community

- transparent document flow and free access to information

- financial management

- interaction of participants in the educational process

Accountability

Ensuring accountability is an important step for addressing the forms of corruption risks in resource management and in academic processes. Accountability-promoting tools in the education sector include performance-based contracting, teacher codes of conduct and complaints mechanisms (Kirya 2019: 3).

Accountability first relies on the ability to detect corrupt acts. Reporting channels can facilitate this, but they should be confidential and safe to avoid possible retaliation against those who report (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017:10). This is especially relevant in the education sector where school employees might retaliate against students or the children of parents who report; however, the reporting mechanism should also be usable by officials in cases where the corruption has been initiated by a student or parent.

The Law of Ukraine on Prevention of Corruption (2014) establishes a robust whistleblower protection system (Chernovol 2023). While it is applicable to all sectors, there is scope for scaling up awareness of this system specifically in secondary education.

Accountability also entails sanctioning corrupt behaviour. For example, Kolomoyets et al. (2021: 709) recommend the mandatory dismissal of education sector employees found guilty of corruption offences, such as bribery. It can also take the form of criminal sanctions and fines, although Huss and Keudel, (2021: 47-8) note that, despite the existence of strict regulations on crimes such as embezzlement, very few cases reach the court and are prosecuted.

Effective sanctioning can also be carried out in the form of a code of conduct stipulating expected behaviour. Albisu Ardigó and Chêne, (2017:10) state that such codes can improve integrity standards, especially where they are accompanied by staff training and provide for clear and timely remedial action in the event of breaches.

The NGO Смарт Освіта (Smart Education), in partnership with MES, developed, through a bottom-up approach, a memorandum of cooperation template for schools. The template sets out rules of cooperation between stakeholders such as parents, students and teachers, but it is a flexible tool which can be adapted to each educational institution (Нова українська школа n.d.).

The NACP (2022) recommends the development and adoption of a “teacher's code of ethics as a measure to tackle private supplementary tutoring”. Similarly, the OECD (2017: 104) recommends a flexible approach to regulating private tutoring by, for example, authorising teachers to provide private tutoring in a transparent system but prohibiting them from tutoring their own regular students.

External checks

Reducing the high level of discretion granted to officials and teachers in academic processes, such as grading and admissions, can make it more difficult for them to be distorted by bribes and favouritism. Similarly, the NACP risk assessment (2022: 73) recommends that electronic queuing systems for enrolment should be mainstreamed across all schools.

A notable example in this regard is the Bloqly system, which is used, for example, by the Drohobych city council to manage registration for municipal schools. The system is grounded on Blockchain technology, meaning registration applications in the system are given extra protection from manipulation (Transparency International Ukraine 2019).

In terms of testing, the OECD (2017: 69) recommended that the Ukrainian education system “make wider and earlier use of low-stakes, external and independent assessment to improve the consistency and integrity of marking”.

Currently, such an assessment is provided only in the form of external independent testing (EIT), which was introduced in 2009 and is administered by the Ukrainian Centre for Education Quality Assessment (CEQA) (IAB-Forum 2022). Several voices in the literature (Kolomoyets et al. 2021: 702; Zhurzhenko 2022) hold that the establishment of EIT considerably reduced corruption risks associated with admission to tertiary level educational institutions. Therefore, the EIT could constitute a model which could be scaled up for other forms of testing in secondary level institutions.

Additionally, the NACP (2022: 80-81) recommends that MES provides guidelines on school assessment principles and methods and for schools to ensure teachers adhere to these closely.

Civil society involvement

Jenkins (2023) highlights the importance of the engagement of non-state actors and local government in reconstruction efforts in Ukraine. Due to their proximity and access to local levels, partnering with civil society on anti-corruption measures in the education sector can facilitate bottom-up approaches with greater involvement of teachers, parents and students, as well as facilitate greater accountability (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017:10; Kirya 2019: 44).

There are currently some civil society organisations active in this space in Ukraine.

For example, Edcamp Ukraine is a teacher led organisation which, among other things, promotes anti-corruption in schools. Transparency International Ukraine has published of handbook to help parents monitor spending in schools, and created an online map of school tenders in 24 regional centres of Ukraine as part of its Dozorro initiative. Смарт освіта is an NGO engaged in the development of the school education system in Ukraine by, for example, training teachers on integrity measures.

- See, for example, Osipian, A. 2018. How corruption destroys higher education in Ukraine.

- Local government units is, for the purposes of this paper a catch-call term to describe local self-government authorities in 1,470 (with Kyiv) amalgamated territorial hromadas or communities (ATH/ATCs), regional state (military) administrations in 25 regions (oblasts) and district state (military) administrations in 136 districts (rayons). ATCs and districts are new administrative units of the lowest and middle level, respectively, formed as a results of decentralisation reforms by 2020. In this Helpdesk Answer, the term city/village council is used to define a local self-government authority of an urban or rural ATC, respectively (Keudel 2024: 30-31).

- For an overview of Ukraine’s anti-corruption ecosystem, see Huss 2024. Anti-Corruption arena in Ukraine: Status quo and dynamics, in BGK. 2024. Towards growth-enhancing state and business relations in Ukraine.

- For a comprehensive overview of the risks and corresponding recommendations identified in the report, the reader is invited to consult the entire report: Національне агентство з питань запобігання корупції (NACP). 2022. Стратегічний Аналіз Корупційних Ризиків У Дошкільній Та Загальній Середній Освіті.

- The understanding of cheating in the survey encompasses practices which may not amount to corruption, such as students copying from each other.

- As of March 2024, the Open School Platform was no longer active. A consulted expert said this was mostly due to a lack of institutionalisation of the platform, as well as the diversion of resources triggered by the Russian full-scale invasion.